Abstract

This chapter will address the philosophical and ethical perspective that corruption, in its many forms, is embedded in most societies’ fabrics as well as justified and rationalised. The chapter will examine corruption and its negative influence on societies by allowing for ethical pluralisms, i.e. Aristoteles and Confucian thought. We will attempt to discuss this from a global ethics overview that tries to avoid imposing a Greek and western lens and that should conjoin shared norms while simultaneously preserving the irreducible differences between cultures and peoples. We have three main objectives for this chapter. Firstly, we will explore the argument that in any culture, corruption in its many forms, may it be guanxi, bribes, political favours, bribes, are covered by the traditional understanding of some types of ethical/philosophical judgement. Secondly, we critically analyse how corruption may have positive effects under some circumstances. Thirdly, we attempt to help the reader better comprehend the diversity in legislation and approaches by governments and the inherent conflicts for both multinationals and companies that are internationalising. Thus, we discuss the impact of globalisation on corporate governance and the current anti-corruption measures many nations are trying to both implement and superimpose globally through their home-based multinationals.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Corruption

- Philosophical perspective

- Ethical perspective

- Moral codes

- Multinational companies

- Globalisation

Introduction

This chapter will address the philosophical and ethical perspective that corruption, in its many forms, is embedded in most societies’ fabrics as well as justified and rationalised. The chapter will examine corruption and its negative influence on societies by allowing for ethical pluralisms, i.e. Aristoteles and Confucian thought. We will attempt to discuss this from a global ethics overview that tries to avoid imposing a Greek and western lens and that should conjoin shared norms while simultaneously preserving the irreducible differences between cultures and peoples.

We will also attempt to analyse corruption both from the western philosophical view of ethical behaviour, which focuses on ethical principles alone, as an independent code not connected with any other beliefs, and from the eastern religion/philosophical view of ethics that blends both belief and practice. In addition to defining corruption based on these philosophical and ethical perspectives, we will also approach corruption with respect to its impact on business from Multinationals (MNEs) to SMEs and start-ups by looking at it from rights, utilitarianism, and virtual theory.

We have three main objectives for this chapter. Firstly, we will explore the argument that in any culture, corruption in its many forms, may it be guanxi, bribes, political favours, nepotism to direct coercion, and bribes, are covered by the traditional understanding of some types of ethical/philosophical judgement. This argument contests long-held views that there can be no universal ethic. Secondly, we critically analyse how corruption may have positive effects under some circumstances. Thirdly, we attempt to help the reader better comprehend the diversity in legislation and approaches by governments and the inherent conflicts for both multinationals and internationalising companies. Thus, we discuss the impact of globalisation on corporate governance and the current anti-corruption measures many nations are trying to both implement and superimpose globally through their home-based multinationals.

Historical Ethical Overview of Corruption

This section will explore the evolution of morality and ethics in the Greek-Western and Eastern societies concerning corruption. The section will delve into the diverged ethical views from these societies and how these differences create uncertainty when defining corruption.

Moral Foundations of Humanity

In the beginning, there were morals among the slowly emerging human tribes and their societies. The initial power structures of these early civilisations suggest that a set of moral codes were a part of emerging religious developments. These moral codes were either verbal like, the Popul Vuh for the Mayan people or written for the Egyptians, Mesopotamians, and Israelites. These codes were also interwoven within the religious text giving these people a clear code of conduct that was spiritual, societal, and political. Therefore, through these moral codes enforced by the dual power of the ruler and the priest, the balance in the tribes, societies, and empires could function (Duiker and Spielvogel 2010; Spence 2017).

However, it was soon discovered that these codes were not enough for growing societies to function correctly. The existence of only religious principles as a way to deal with the increasing complexity and detail of issues as society evolved, required a more detailed and objective approach. The answer was in creating laws, such as the Hammurabi code, that dealt with much more specific issues of everyday life in his empire. These codes may have had religious overtones, but many of them were practical solutions to recurring problems. An example of these issues was the need not to pay rent to the landowner if a crop failed due to weather issues (Hammurabi 2018). This may have led to initial conflicts between the moral/religious code and the legal/social laws established by rulers prompting the beginning of a separation of ‘morality’ or moral code from legal code. With influential religious and political organisations bestowed upon the ruler, some civilisations such as the Egyptians tried to combine both and solve some of these issues. On the other hand, others like Hammurabi, who built an empire in his lifetime that quickly dissolved after his death, were more focused on the administrative powers of the State.

The Early Rise of Ethical Issues in Corruption

The growing tendency of tribal assimilations of the weakest ones by the strongest in languages and cultures required a more flexible approach to imposing moral and new legal codes. With this population and territorial growth came economic growth, quickly followed by the creation of an administrative bureaucracy to manage the conquests. The transfer of powers that had previously only resided in the rulers’ hands resulted in payments for services or favours. In Hammurabi's code, we find one of the first allusions to this abuse of power: ‘Deprivation of office in perpetuity fell upon the corrupt judge’. However, the code does recognise the notion of intention, which may be seen in the idea that human actions may have motives driven by thought and decision-making rather than by belief or instinct. This could be the precursor of humans dealing with ethics. This idea of intent, together with customs, helped the institutionalisation of corruption rather than prevent it.

In Mesopotamia and several Indian kingdoms, both favours and economic gains were respected as a reciprocity practice. The wrongdoing is not in the act of making an exciting gift but instead in breaking with the underlying reason for the exchange: in failing to offer value in exchange for value received (Gaustad and Noonan 1988). Gaustad and Noonan (1988) also add that the most severe misdeed was not in the act of corrupting but in the effect of corruption. Breaking one's word was the real crime in a society where keeping one's word was a divine characteristic. This again brings us closer to the idea not only of what lies behind the actions and what should lie.

Greek and Western Ethical Views of Corruption

The religious power structure was not immune to the same effects; the bible is littered with references of corruption from Eve to the apostles and Judas. The religious rites required payments for favours adding to this idea of reciprocity. However, this idea was slowly rejected by some societies who saw it as an unfair state, especially for those disposed of raising the idea that equality is a virtue rather than a moral obligation. The theme of corruption is very much at the centre of Greek mythology, with Zeus casting all evils into pandora’s box to protect humanity. Greek philosophical thought is driven at times to deal with the individual, the State, and the corruption that power, in any form, brings with it. The search for the incorruptible individual leads Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle to seek the just and ethical ruler. In the view of these philosophers, the individual should seek pure reason and leave the world of politics since it is within this realm of the senses that change and decay inevitably happen, opening the world to inevitable corruption (Basu and Cordella 2018).

Greek philosophers incorporated elements of religious traditions into their teachings insofar as they served to validate their premises. This is a continuation for society to move away from having religious, moral values, and codes at the centre of human actions. Plato (1979, 2012), in the Laws and the statesman, sees a notion of the non-corrupt individual as the ideal ruler type. Thus, for him, the truly virtuous man should rule (as an absolute ruler) or a group of honourable men through a wider aristocracy. The inferior State, in contrast, suffers from a form of fthorá or ‘decay’ (adapted by the Romans later as corruptio). The roman meaning of corruption falls in line with a description of deficiency, lack, or fall from the ideal. It also contrasts with our modern view of corruption that is part of the political system rather than a degeneration of one (Mulgan 2012).

In the way most western scholars and the vox populi define the word, lies the ethical debate around corruption. This idea of a state falling from ‘grace’ or an ideal follow the Greek philosophers, centring it on the ruler and his selfless obligations to the State, and by default to its citizens. Many of these ideas were eventually adopted by the Romans, who assimilated much of Greek civilisations as their own. Where the Greeks were concerned with the ruler of the city/state, the Romans quickly understood that politics and politicians played on a much bigger stage as the empire was carved out. The State was to be governed by individuals who were not gods, but citizens entrusted by citizens to be above the material necessities to ensure the health of the State. This in itself did not mean they did not, or in some cases, should not engage in actions that we would call corrupt today. The buying of the popular vote was rife, and buying favours from the gods was a must. It could be argued that this harkened back to reciprocal favours being exchanged and coinage made it more straightforward and more transparent. It could also be said that buying votes is more ethical than lying to the electorate about what you will or will not do once in office.

Both Greece and Rome recognised that once in office, some forms of decay would be inevitable. However, this was mostly restricted to forms of gift or favour, accepting which resulted in some type of ‘detriment to the people in general’ as Demosthenes describes it in one of his speeches. It should be noted, however, that plunder in a war at the service of the Roman republic, ‘Senatus Populusque Romanus’, by armies paid by the public purse, were not unethical or considered corrupt, and the State expected, in turn, its share of the plunder. This contradiction between an internal moral and ethical standard and an external one that is devoid of ethics, as in times of war, is one that has continued to fuel conflicts in western states. The corruption of the ideal ruler leads both Greeks and Romans to seek republicanism and escape tyrants and kings since the concentration of power leads to the individual's and, by default, the State's corruption. It is the failings of the mind that leads to character flaws in the individual and the loss of virtue. The citizens were also at fault. Instead of demanding and ensuring that the State fulfilled its contract with itself, they allowed themselves to also partake in the decay. As Tacitus describes it, Augustus seduced both the population with corn and the soldiers with gifts (Strunk 2016).

Medieval Europe, the enlightened and pre-revolutionary European states, for the most part, reverted to the notion that kings, and sometimes emperors, were the State. With few exceptions, rulers in Europe and the emerging Arab empire were the embodiment of the State with usually openly stated ‘divine’ mandates with the full support of the religious powers. King after king needed the Pope's blessing and sometimes even permission to rule. This gave them not just vested authority but the moral one also. Having a child with your daughter was morally wrong but having a rival executed so you could have his wife was not. Ethics rarely came into play, and the Greek philosophers had been conveniently forgotten. Corruption was again defined by excessive greed by those serving the rulers and not the acceptance that servitude to the king brought within it its own intrinsic rewards. The world was back to accepting that reciprocal favours were the norm with the understanding that one's word was the value that mattered. When Luis XIV uttered his famous ‘L'Etat c'est moi’—I am the State—he was not full of himself, he just saw himself as France and France was him. There was no dividing line.

Corruption under Luis XIV was defined as taking from him, not the State per se. The church solved the moral conundrums of the era. Sometimes indirect collusion with the rulers and straining the relationship between the regnum and the sacerdotium, while ethics were the preview of the church authorities and the newly emerging intellectual class rather than the rulers. When kings found their lack of morals questioned or power checked in any way by the church, the solution was to create their own religious brand (Barcham 2012). Newly formed institutions, public and private, had a set of basic rules formulated by the kings, except Britain, which managed to keep some checks on the king’s authority after the signing of the Magna Carta. Corruption per se was punished depending on the individual, with laws and interpretations varying continuously. Post-revolutionary governments such as France and the United States preached ‘liberty, equality, and fraternity’ in various forms while at the same time institutionalising racial and gender discrimination and picking the ethical frameworks that fit those governments (Duiker et al. 1994).

Eastern Ethical View of Corruption

The newly formed corporations such as the East India trading company and the Dutch East India Company operated as quasi-independent states. Their ethical barometer was to provide returns to their investments, nearly at any costs, within the un-fit for purpose laws of the times. Corruption was just a way to accomplish this. Buying the favour of local Indian princes was simply good practice. Creating an environment of uncertainty to instigate a war such as the invasion of China, the Spanish-American war, or the take-over of the Indian subcontinent was just protecting national economic interests. The idea of the ideal State run by ethical individuals only applied to those that were part of the politico-economic class Denoon (2009) and Keefer (2013).

Closer to eastern cultures in its roots, the Arab empire saw its birth and growth governed by a mix of tribal culture and norms and a new set of codes because of the writing of the Koran, which in itself was heavily influenced by Greco/Roman/Jewish religion, philosophy, and laws. The responsibilities of the State to its citizens were clear. The ruler or Caliph had the mantle of Muhammad’s authority and a clear ethical duty to his people and God and governed within a concept similar to the righteous ruler Greek view. This may have created internal tensions between the traditional tribal reciprocity environment that did not see corruption as an inherent issue and the new ideals of community sharing, responsibility, and good government as the empire expanded and encountered both the West and the East. Al-Farabi, a ninth-century Arab philosopher, discusses the inherent dilemma of prudence within the rational measure of ethics (Nicholas 1963).

The Indian and Chinese kingdoms and empires also recognised corruption in its many forms reflects the imperfect nature of any market. Indian scripts as far back as the fourth century, and around the time of Aristotle, clearly realise and explain how it is virtually impossible for a government employee not to taste, at least, a little bit of the kings’ revenue. This acceptance of reciprocal exchange and approval of a tacit acceptance of some rule-bending to ensure the wheels of society keep moving is embedded in eastern philosophy balanced between what is of God and all humanity. Religious quid pro quo is built into sacrifices and ritual where being rich helps win favour with the Gods (Trautmann 2016). In the Chinese empires of antiquity, there was not a definition of corruption per se. The empires were sustained by a system of patronage and rigid bureaucracy. There was also a support for genuine family love within a framework of social justice that is as the core of Confucian ‘ethics’, that is, ‘a basic principle of “mutual non-disclosure of wrongdoings among family members,” which has exerted a considerable influence upon ethical ideas, judicial systems, and social life in ancient and even contemporary China’ (Wang 2014, 112).

The ethics from the East diverged from the Ethics from the West vastly. In the East, we have a system in which all belongs to the State. The emperor or king and a powerful family network that takes care of its own or among its class or caste. This view is significantly divergent from the ethics of the West, which are based on the individual. Then, corruption, in its many manifestations, is not an absolute between an individual and his/her ‘decay’ from a state of moral and ethical perfection. Corruption is a compromise between the real world, its needs, and the obligations to one’s family within the norms of the caste or class. Corruption may actually be seen as something that allows humans to operate in a realm between the gods and the harsh realities of animal survival.

Ethics: A Business Perspective

This section will explore corruption in the business world, differentiating between the ethical perspective of individuals working in a firm and the firm itself. It will then discuss business ethics from three ethical traditions: utilitarianism (Mill), virtues (Aristotle), and the theory of right and wrong (Kohlberg). We have selected these from among many, Deontology (Kant), care (Held), for example, since we feel these relate closely to the main issues at hand, corruption and business ethics. While utilitarianism focuses on the consequences and what to do, Aristotle’s virtue theory helps us navigate the social and individual issues of what type of person we should be as a society. Kohlberg theory focuses more on the processes individuals must go through when deciding if a behaviour is right or wrong.

Differences Between Individuals and Firm’s Ethics

It is common to hear the well-worn cliché that you cannot use the words business and ethics in the same sentence. The commonly held view that companies are inherently ‘unethical’ has been formed over time by the notion that an individual, when he or she acts as a businessperson, the agent stops being him/herself, steps outside the personal ethical and justice confines to succeed (Morse 1999). Indeed, this idea that a business must succeed at all costs has been fuelled by stories of success from the robber barons of Victorian times to the oligarchs of present reality. The film industry has helped fuel this perception by using, in most cases, real stories that depict the individuals as ruthless, a-moral in their dealings, while at times showing a passionate, caring, and loving side in their personal dealings (Belfort 2011). This is not dissimilar from the depictions of soldiers acting one way in the theatre of war and returning to being upstanding individuals in their local communities (Coates 1997). This notion that business ethics and personal ethics are inherently separate and being openly proposed by such individuals as Milton Friedman and Alfred Carr, who forwarded the idea that business practices should disregard societal needs and that the rules that govern business practices should be separate from whatever personal ethics an individual may have (Morse 1999).

This leads us to consider the idea that a business enterprise is in itself a unique entity and thus entitled to its different norms, values, and ethics. The business literature has created a whole sub-genre looking at why and how firms develop their own unique cultures which include a set of opinions, value systems, and behaviour standards is unique for each organisation and represents the specific character of its functions’ (Hitka et al. 2015). These differences have also been attributed to the uniqueness of the enterprise that provides it with a distinct competitive advantage. This uniqueness gives all within its mantle a difference in terms of norms, behaviours, and other characteristics that may force or influence the individual to conform or be separated. De Botton (2008) tells us that humans, by their very nature, want intrinsically to belong and will usually fit accordingly. It cannot be a mere coincidence that business has taken so much from the military. Business courses routinely teach strategy, logistics, and leadership courses that derive much of their background to practices and norms developed in the military. This may seem contradictory when at the same time, students take ethics and social responsibility courses. This separation of roles between the member of the institution and individual ethics and moral values has been a cornerstone of military life, ‘obey your orders no matter what’, and adopted by businesses, ‘get it done or leave us’ in the way they feel they need to act to compete in brutal and hostile environments. The slogan ‘Business is war’ is one that many executives treat as their mantra. Thus, within enterprises, the individual is expected to act within the norms, values, and expectations regardless of their set of beliefs, ethics, and morals. These contradicting needs to define better business ethics have led to many theories. We will consider only three in this chapter.

Utilitarian Theory and Business Ethics

J.S. Mill (1998) proposed nearly two centuries ago that work for common outcomes leads to the greatest amount of happiness for all. Mill's utilitarianism was conceived to make clear ethical distinctions allowing to frame business ethics around three pillars: (1) its shared goal is the common good, (2) it has a long-term perspective that focuses on the prosperity of society as a whole, and (3) it seeks the teaching and support for a moral education within the societies it inhabits by encouraging social concern for the individual (Gustafson 2013). The notion of the greatest welfare for the many through each individual action then leads to ‘the greatest happiness altogether’ Mill (1998). Some argue that this idea of happiness for the many fits business well Gustafson (2013) since its goals are intertwined. The long-term well-being of humanity also bodes well for any business.

Happy, prosperous humanity should ensure the well-being of firms within the business world. This simple but powerful narrative is both attractive and compelling to some. It may imply that it helps those within a business to stay away from short term profit only approaches. On the other hand, some inherent contradictions also arise, should a manager risk the failure of the firm altogether by minimising short term profits for the long-term good of society, with the implication that it benefits the firm also. This, some would argue, is the application of risk to the model. The ethical dilemma that management faces between the need to succeed, the firm’s role in society, and the needs and satisfaction of its stakeholders, which may be not the same as those of society as a whole. How wide or how narrow we want to define ‘society’ from the term global village to the idea of micro-tribes by State, location, city, and neighbourhood is complicated at any level. These contradictions may be exacerbated by the constant flux of tribes, tribes within societies, and societies within nations. The greater happiness for a Belgian firm, for example, is that of the Walloons or the Flemish tribe? Since both seem to agree on very little. Are the greater good environmental solutions that a country may accept one day and negate the next?

Hiring practices that don’t discriminate? Or start discriminating as society shifts from acceptance to rejection of immigrants? An inherent issue for the ethical manager or firm is not knowing where the ethics lie at any given moment within any tribe.

Virtue Theory and Business Ethics

Enterprises have had to deal with the idea that as an entity, they are an integral part of a tribe or society and as such, have a responsibility for it. The more global the enterprise becomes, the vaguer this sense of ethical responsibility to humanity becomes. Yet, stakeholders keep alluding to these ethical responsibilities of the firms. From the environment, sustainability, gender, employment, to tax citizenship, the firm of the twenty-first century is continuously examined, probed, pushed, and found wanting.

Firms are now adopting professional codes of ethics and conduct, writing detailed rulebooks, mandating ethics training for their employees, applying legislation dealing with corruption into their strategies, and dealing with the consequences when employees fail to live to these principles and standards. Academics point out studies that link corporate social responsibility measures with improved financial performance (Roman et al. 1999), failing to mention that the samples of the studies did not take into account all the firms that failed or were acquired and had also integrated the same principles. The point here is not to minimise the value of this research but to highlight the complexity in measures that try to put a value on a firm's ethics. The key issue, therefore, is defining the standard to which a firm as a tribal or societal entity is expected to adhere to. The need for codes of conduct is not just a moral need but a practical one. Laws are a reflection of some of the ethical standards of a nation. These laws are written for common clarity, adopted by all, and set a tone as to what society expects from its citizens: individual and institutional. Laws help business executives make sense of a lot of the abstraction and rhetoric that precedes writing and approving them by giving a clear direction as to expectations and how to formalise these in actions everyone in the firm can understand.

While traditional views of virtue revert to Greek philosophy and focus on rights and duties, a more modern version of virtue ethics or theory that was proposed by Arjoon (2017) is based on three assumptions, (1) the environment or a dynamic economy, (2) the mission or common good, and (3) the core competencies or virtues. These assumptions, in turn, must fit reality and one another. Virtue theory is thus not devoid of its Greek heritage and the notion of excellence needed to complete tasks well. Virtues in this context can only be appropriately formed or acquired by constant repetition and practice. This practice is required to create a moderating effect between passions and actions, both of which are excesses on either end. These desires and purposes of the individual are equally reflected in the collective that forms the firm. As such, the firm is part of the society that sets the ethical standards and should be subordinate to the ultimate goal of the community (Morse 1999). The virtuous firm emerges from this imagery in a form not very dissimilar from the ideal leader for Aristotle. However, the modern firm has to deal with a complex set of ethical values and expectations far removed from the relative simplicity of the Greek city/state. Internationalisation and globalisation put it at odds with different ethical frameworks and expectations and create the dilemma of what model citizen it should be and whose virtues it should make its own. When its ‘home society’ reflects its ethical values in laws that punish corruption, definitions notwithstanding, and expects it to implement these within all the other societies it operates in, it imposes a set of arrogant principles that in themselves may be considered less than ideal. Also, this same ‘home society’ may, due to changes in political winds, act in open defiance of its laws at a point in the future, leaving the firm with an indefensible ethical position, regardless of the written law.

The Theory of Right and Wrong and Business Practice

The theory of right and wrong is the least developed and explored academically. In some ways, it may be because of its inherent simplicity that harkens back to early civilisations and ethical development. As discussed earlier in this chapter, most early religious script and codes of law derived most of their moral backing by differentiating the good (right) from the bad (wrong). Tribes, extended societies, and nations have always attempted to address these differences and legislate them with a base code of laws. The Hammurabi code, the Koran, the Popol Vu, and The Bible, among the many, provide the basic blueprint to help tribes and societies identify ‘wrong’ actions into identifiable actions and implement corrective actions.

Businesses and governments have both historically engaged in practices that are ethically wrong, although legally acceptable or ambiguous, by arguing that the wrong actions are done for the greater good. The internment of the Japanese by the US government was justified on a national security basis at the same time as it criticised German concentration camps. Today most would agree that both were ethically wrong. Within a business context such as medical research, testing inmates without their consent, for example, or arms and weapons creation, manufacture, and distribution have been condemned by many as ethically wrong. However, they are justified on the grounds of national security or the greater good. Governments have reacted to medical research malpractices by passing laws that deal with principles of ethics in all research and with them a code of conduct based on respect for the individual (Jacques and Wright 2010) and encapsulating the basic moral principle of ‘don’t do unto others what you would not have them do to you’.

The moral ambiguities that religious texts had built-in within them necessitated the evolution of the theory of right and wrong, which is more universal than the ethics theories developed mainly in the West. This more straightforward theory allowed for tribal and societal changes to be incorporated and modified over time without the issues found with questioning religious code. Slavery is an excellent example of these ethical and moral contradictions. In the bible, the Israelites celebrate their liberation from slavery as an act of a compassionate God. Yet both the old and New Testament is full of veneration of slavery. The Hammurabi code has specific rules on how to treat slaves; the Koran, although not explicit in its acceptance, does not prohibit it either. All of these positions reflect the way societies and tribes operated in those times in which slavery was widespread, accepted, and a source of ‘economic good’. Slavery was a major source of income for individuals from the British to the Arab empire. While this trade developed, neither the Catholic Church, protestant preachers, nor Islamic religious figures openly condemned it. The enlightenment recognised this abomination and used ethical arguments to enact laws stopping the trade in the West or economies controlled by the West. The tacit acceptance by the Koran of slavery in the Islamic empires and subsequent nations was only abolished in the twentieth century not so much on moral or ethical grounds but because of the pressure from western states and general international condemnation. However, countries like Mauritania and South Sudan still have today an active slave trade.

Right and wrong theory may help firms navigate through societal differences, and this may be particularly true concerning corruption since the term itself is full of ambiguities and interpretations, norms, and laws.

Ethics, Society Corruption, and the Individual

If governments and religious power structures have formed and shaped the codes and laws that tribes and societies used to set and ensure ‘live and let live’ environments, one may ask, where was the individual in this process? The balance between what I want and need must always be measured against what my neighbour wants and needs. As humans settled down for the first time in the Levant it by necessity required some basic rule forming (Hodder 2012). The traditional family that roamed and hunted and gathered and could do what it pleased found itself with neighbours that had done the same. The inherent tensions and inevitable fights and disagreements required intervention, negotiation, and compromise. These, after a time, got codified, adapted, and enforces differently as each tribe agreed on common ground within its cluster of habitation, usually with religious overtones. The idea of what is good or bad behaviour took a local flavour that as tribes grew, eventually merged and/or conquered other tribes required probable changes from ‘pure’ good and bad definitions to acceptable and unacceptable behaviours. Some of these already had subtexts that a modern human would find offensive since there are no moral principles that have been found to be shared by all religious people, no matter what specific religious membership they belonged to (Hauser and Singer 2005). For example, the idea that adultery is a ‘bad’ thing in the Old Testament was clearly male-dominated enforcement of their insecurities as to whom fathered their offspring and started a pattern of subjugation of the female gender that endures to this day. Many other tribes were polygamous as local conditions required that all resources were shared in order to ensure the survival of the tribe. Thus, the individual moral code of survival and duty only to its nuclear family gives way to agreed norms that were enforced by the majority. This brings us to the underlying question: Does the individual sense of right and wrong, in turn, shape the tribe's sense of right and wrong? And since these do not appear to be universal, do tribes/societies, in turn, adapting to their internal politics, surroundings, and ambitions mould and change those of the individual? We believe that reality lies as most thing somewhere in between these two and are adapted, fine-tuned and enforces to satisfy local differences, times, and needs.

Corruption in this context has always been an adaptable societal norm: encouraged, tolerated, and shunned. The Romans imported Greek ethical thinking and adapted it to their own needs and wants as the empire grew. The idea of the purity of the politicians in the Senate quickly gave way to the practical necessities of running a vast empire. Decisions would never satisfy everyone, and the individual was encouraged to sell his favour in order for them, in turn, to be able to buy the votes and vox populi required for them to continue in office. The Roman State would customarily extort goods and services from the civilian population for its soldiers. This practice got so extreme that it took individuals to draw a line in the sand. Gnaeus Vergilius Capito, who was the Prefect of Egypt during the reign of Emperor Claudius, went as far as issuing a public edict ordering the end to these demands by military personnel (Lewis 1954). The State, society, and the individual have always had a difficult relationship with regard to ethical and moral issues, particularly in the West. Fast forward to the twentieth century, and the system of patronage and dispensations of favours is superseded by political lobbies, vote-buying, nepotism, and clientelism by elected officials as democratic states took over. The great proletariat experiment that led to the creation of the USSR and the PRC eventually degenerated into a system of patronage and favour granting that dictated all aspects of Soviet life, from where you lived and studied, to what you had for dinner, and what you did for work. The fall of communism and the rise of the oligarch/FSB ruling system just exposed for a while these deeply seeded behaviours that have continued to the present day and that, although refined, for the most part, remained at the systematic and societal wide level of corruption that operated previously (Stefes 2006). These practices, also present in China and other eastern nations, are not seen by Russians as ‘corruption’ with a big C, but as a way to get along in a society full of rules, laws, and regulations that are contradictory and nonsensical. From the Russian citizens’ point of view, блaт (the system of informal agreements, exchanges of services, connections) allows everyone a certain amount of access to the power structures, speedy delivery of services and equality. A little блaт to a traffic policeman allows you on your way, you have been admonished by the system for driving too fast, and it has avoided endless visits to a slow and inefficient court system. Thus it allowed the reallocation of power that would have been too concentrated in the hands of a few judges.

Can any Positive Come Out of Corruption?

The previous description of utilitarianism, and virtues and right and wrong theory, as well as the roles and societies, presents the key argument for each of them and the notion that each ethical theory faces challenges that open them to interpretations. The utilitarian theory explains, in addition to its inherent measurement problem, a controversy concerning the dimension of what to consider to be ‘society’. The justification of an act based on virtues theory will depend on time and space because these elements are essential when evaluating culture and society values that shape the ‘virtues’, which is the basis of this theory, and a broad definition of what is right and wrong leads to ambiguities and multiple interpretations. These blurred aspects of ethical theories can, on some occasions, justify even the undesirable act of corruption. This section aims to explore these arguments and the empirical evidence that supports them. Although there are many of these in all areas of ethical behaviour, we will only focus on those relating to corruption.

“Justification” of Corruption from the Philosophical View

The theological or consequentialist perspective considers the decision to be right or wrong based on the potential consequences and whether good or harm results from the action.

Thus, it follows Machiavelli's saying that we all know, ‘the ends justify the means’. The utilitarian theory, a consequentialist theory, considers an act to be morally right if the benefits created by the consequence outweigh the cost of this action. A cost-benefit analysis is needed to understand if the greater good prevails. An important aspect of this theory is that it does not judge morality or a predetermined set of ethical standards like the right and wrong ethical theory. Therefore, regardless of where the corrupt act is done and the social values of the country where the act is performed, corruption could be justified if the corrupt act leads to the greatest good. In fairness, it can be contended that it is impossible to evaluate corrupt actions in this way, not only because what needs to be measured might not possibly be measured but also because, in real life, ethical decisions are not chosen based on an in-depth analysis.

In contrast to the utilitarian theory, the virtues theory does not focus on consequences but on intent. In virtue theory, social values are essential to consider an act to be moral, but they are not the only and ultimate pillars. The motivation of the action is also relevant and this, according to Sandel (2009), should be embedded in the sense of duty. Therefore, a corrupt act can be morally justified if the individual embarks in the act because he or she has a sense of responsibility and not because there is self-gratification or self-interest.

Like the virtue theory, the right and wrong theory considers the social values of a specific society at a particular time, but in this case, these social values are the pillar of the theory. Thus, a corrupt act is considered acceptable if the system of beliefs and customs that exists at the time and place where the corrupt act is performed considers the action permissible. For instance, bribery in western society is considered not only unethical but also unlawful. However, in other parts of the world, bribery can be regarded as simple tipping, and therefore, there is room for the action to be justified.

The previous section shows that on ethical grounds, corruption could and is justified depending on the underlying structure of society's ethical underpinnings. However, this may be the outcome of a historical struggle to arrive at that position based on cultural, moral, and intrinsic individual qualities needed to reach this controversial reasoning. Besides, there are other determinants of unethical conduct, such as the risk involved. Napal (2001) explains that the decision-maker may choose not to participate in dishonest acts not because it is wrong in absolute terms, which will be the argument from the right or wrong theory, but because the individual is afraid to be caught. These pieces of the puzzle can be a partial explanation to comprehend something that perhaps many of us have asked ourselves before, why good people do bad things.

This attempt to justify corrupt behaviour from different ethical perspectives goes against the classical conclusions of business ethicists, and few scholars have dared to claim that corruption is efficient. Leys (1965) went so far as to wonder, ‘what is the problem with corruption?’ He also questions under which circumstances are actions called corrupt (Leys 1965, 217). He answers this by postulating that ‘because someone can regard corruption as a bad thing, but others (at least someone) can regard it as good, mainly the ones involved in the act in question’ (Leys 1965, 219). Nevertheless, this remains a very controversial statement constantly up for discussion in academic circles.

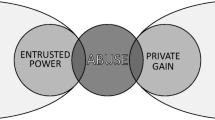

The Fair Treatment of the Term Corruption and Businesses

The most common tradition is to discuss the possible consequences of corruption as unethical behaviour, and much of the ethics research primarily alludes to the adverse effects that corrupt practices can have on a firm. These arguments are far easier to make and understand, but that does not mean that the debate about possible positive outcomes does not exist.

In the academic literature, the corruption outcome debate is operationalised in two main hypotheses: the ‘sand on wheels’ contends that corruption reduces efficiency and ‘grease on the wheels’ that hypothesises the benefits of corruption. The ‘grease on the wheels’ hypothesis is rooted in arguments of the so-called revisionists or ‘functionalists’. The theory argues that the problem is not the act but the reason behind the action. The core issue comes from the ineffective bureaucracy that impedes economic activity. But corruption, it is argued, can help to speed or ‘grease’ money because firms’ corrupt actions would help to overpass ineffective policies.

The reasons for ineffective government policies can range from the mere capability to biased ideology to prejudice against certain minorities. An example given by Leff (1964) shows how Chile and Brazil bureaucracies responded differently to price control for food products introduced in both countries during the 1960s when in Latin American, inflation led to stagnation of food production and the rise of food prices. Both countries enforced price control. Chile bureaucracy loyally implemented the measures, and in Brazil, the corrupt bureaucracy sabotaged the enforcement allowing producers to increase the prices. Somehow the Brazilian economy responded to this price rise with an increase in food production and partially curved inflation. Leff (1964) saw this as a clear example of how firms and corrupted officials succeeded in yielding a more effective policy than the government imposed.

Leff (1964) also argued that if corruption is a means of tax evasion, it can reduce tax collection, and corrupt individuals can allocate these resources to other investments provided that they have efficient investment opportunities. In this case, corruption is an effective way of choosing investment projects because some projects required licences. Leff argues that bribes are allocated to the most effective generous briber who can only be the most efficient.

Méon and Weill (2010) state that corruption can be also beneficial by improving the quality of bureaucrats. As Leys (1965) claimed, in countries where public servants gain low wages, the possibility of gaining bribes may attract more capable bureaucrats who could have worked somewhere else otherwise. Thus, corruption is, in general thought, to grease money to compensate for deficient institutional frameworks. Méon and Weill (2010) argue that it is worse to have ‘a rigid, over-centralised and honest bureaucracy than a rigid, over-centralised and corrupt bureaucracy’.

On the other hand, the ‘grease on the wheels’ hypothesis rebounds each of the previous arguments assuming more self-interest bureaucrats. Therefore, overpassing ineffective policies is not realistic because (a) delays can appear as an opportunity to extract a bribe (Myrdal 1968 as cited in Pierre-Guillaume and Khalid 2005) and (b) the power of civil service to speed up processes is limited in a system with continued successions (Pierre-Guillaume and Khalid 2005).

The argument according to which corruption helps increase the quality of investment projects is contested for public investment because corruption has been associated with unproductive investments (Tanzi and Davoodi 1997). At the aggregate level, the impact of corruption on civil servants’ quality is refuted because corrupt officials can create distortions to preserve illegal economic source (Kurer 1993).

The corruption debate has encouraged scholars to investigate whether corruption could have a positive or negative impact. These empirical studies have investigated, at the national level, the impact of corruption on economic growth, direct investment, income inequality, human development, natural resources, innovation, shadow economy, brain drain, fiscal deficit and human capital, and others. Research has explored the impact of corruption on private firms’ profitability, firm growth, firm performance, entrepreneurship, and increased sales and productivity at the firm level.

Rock and Bonnett (2004) found evidence for support of the ‘grease on the wheels’ hypothesis in their study of the ‘Asian paradox’, which is the combination of high corruption and high growth in countries like China, Indonesia, South Korea, and Thailand. Corruption was found to increase growth in these countries. They argue that central governments in these countries could use their discretionary power to support specific entrepreneurial groups. Johnson et al. (2014) evaluated corruption convictions and economic growth from 1975 to 2007 in the United States. They found that corruption’s negative effect is smaller in States with more regulations proposing a ‘weak’ form of grease on the wheels’ hypothesis.

Dimanti and Tosato (2018) provide a thorough overview of the empirical evidence of corruption’s impact on economic growth, investment, poverty, and other governance indicators. The main economic lessons from Dimanti and Tosato (2018) find that solid institutions’ presence lowers corruption. Cross-country macro-econometric evidence provides somewhat limited support to the view that corruption greases the wheels of growth, with trade openness and institutional quality appearing crucial factors in mediating corruption’s effects on growth.

Urbina (2020) did a comprehensive survey of the existing literature on the impact of corruption at the macro level. They focused on five outcomes: economic growth, direct investment, income inequality, human development, and the natural resource sector, but they acknowledge that there are other aspects by which corruption can benefit the economy. The revision showed contending results in economic growth, direct investment, and income inequality but a more substantial consensus regarding negative consequence for human development and natural resources. In fairness, Urbina (2020) claims that the evidence suggests that corruption is detrimental to the economy’s functioning overall.

At the firm level, Imran et al. (2019) found that firm's sales and exports increase at the aggregate level for 147 countries. However, when data is disaggregated, these findings hold only for low and middle-income countries, and the opposite is true for high-income economies. In another study, Martins et al. (2020) found that on a sample of 117 emerging and developing countries, regardless of the proxy variable used as firm performance, corruption affects performance negatively. However, the negative effect is mitigated for larger and exporting firms. Moreover, ‘grease of the wheels’ is found in African firms and ‘sand the wheels’ in Latin America, the Caribbean, Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and Southern Asia.

The empirical evidence is not yet conclusive. Corruption is one of these concepts challenging to quantify and test, and there is still the question of corruption being the solution to the market or the result. Still, overall, the evidence suggests that more than it being a black and white outcome, the result and extent of the impact of corruption is conditioned to cultural and institutional factors.

The purpose of this review is to inform of the contending arguments that challenge corruption. This is crucial for reflective thinking and, therefore, a precondition to gain a stronger sense of tolerance in our personal life and comprehension in our business endeavours.

Corruption in a Globalised World

As discussed earlier, globalisation is not a new phenomenon; what has changed is the speed and breadth of enterprises that call themselves global. Deregulation and technological advancement triggered a quick expansion of Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) all around the globe. Many of these enterprises are not from the traditional western developed economies but reflect the growing economic power and relevance of previously called underdeveloped economies. From Korea and Taiwan to China, Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa, these fast-growing MNEs are changing the landscape of the nature of multinationals and how they are viewed. Corporate cultures are formed by the distinct tribal norms, values, and ethical perspectives of their home base. These differences are also informed by local laws, customs, and accepted behaviours that may and can differ significantly from those in traditional MNE creating countries in Western Europe and North America. Thus, the competitive landscape has and is altering globally, placing western firms at a disadvantage by having forced legal and regulatory straitjackets based on sometimes outdated or culturally imposed views of ‘good’ ethical behaviours.

The rise of global capitalism poses new ethical dilemmas for MNEs all around the world. Increasing wages and employee access to comparative data, greater transparency in environmental and human rights, as well as ever-growing regulation in developing countries pose a constant ethical challenge that is yet to be resolved. This is where the business ethics field seeks to answer a critical question. Is there a practical approach for the ‘ethical cancer’ that many MNEs face while operating in developing countries?

In this section, we explore the diversity in legislation and approaches by governments. We also touch on the inherent conflicts for both multinationals and companies that are internationalising. Thus, we discuss the impact of globalisation on corporate governance and the current anti-corruption measures many nations are trying to both implement and superimpose globally through their home-based multinationals.

Ethical Challenges in Multinational Businesses

In a globalised world, the line between corruption and the ethical principles that in turn drive the creation of laws and their compliance can be a fine one. MNEs and those who work for them must act ethically wherever they go. However, the cultural and legal dimensions of ethical behaviour in a global context get more complex and their implementation more complicated.

Enterprises that internationalise have to rapidly learn and internalise this knowledge while maximising their firm-specific advantages (FSA). The aim of any firm, and, in particular, those that expand beyond their home markets, is to secure a lasting stronghold in a chosen market. To do this, the firm needs to leverage its resources, minimise the effects of its liability of foreignness, and be competitive from the moment it enters the new country. Its firm’s FSAs will thus condition the international expansion of a firm by exploiting those it already has and exploring new resource combinations, and creating new FSAs, and this continuous process has at its centre the entrepreneur or managing team. Their judgement is essential to making the best choices and decisions to combine and deploy resources to implement best the firm's value-capture and value-create goals (Verbeke et al. 2014).

Ethics, Corruption, and the Law

Production facility relocations to emerging countries became the common denominator for companies in the 1980s and 1990s. This followed a period of heated internationalisation by mainly European, North American, and Japanese firms, which, following the Uppsala model of Vahlne and Johanson (2013), sought to capture markets outside their home base as they found domestic growth more challenging to come by. The standard model had firms keep their R&D and core manufacturing at home while establishing smaller commercial offices and plants in host locations. Internationalising firms both learnt to balance risk and opportunity and internalise this learning to extract rents in order to provide growth, and usually better margins than their home countries, while at the same time, keeping the firm on a strong competitive footing viz their competitors. As more companies became true multinationals, they also had to deal with an array of issues and barriers that ranged from specific investment rules and controls to cultural and ethical issues they may not have been exposed to in their home markets. While some companies had a long history in dealing with international markets and these issues, the 1960s onward brought many novice firms into the international arena. Corruption was, in general, something that firms dealt with in a fashion that reflected the firm's roots and tribal background. Thus, two Belgian firms may have taken two completely different approaches based on their tribal knowledge, a practical approach if coming from the Dutch-speaking province and a potentially more ambivalent approach if from the French-speaking side. In some cases, the ethical approach of a firm would have resulted from the company’s history either as a colonial power or an opportunist trading one.

The invasion of Cuba and the Philippines by American forces during the specially created Spanish-American war had barely disguised commercial interest for American firms needing new markets for domestic overproduction (Ninkovich 1999). The establishment of the British Raj and expansion of the empire into Malaysia and Africa, both seeking markets for British textiles but also sources of cheap raw materials for the industrial revolution, were never disguised as other than the need for expanded commercial opportunities for British traders and enterprises (Huttenback 2003). The post-second war post-colonial era resulted in the end of colonialism and the growth of the multinational. Although their links were less visible, some nations supported their firms with political muscle and even direct support. Industries such as defence and oil were seen as critical, and governments used their influence on securing contracts and preferential treatments by less-developed nations. However, it was not just in emerging nations. One of the largest corruption cases in the 1960s and 1970s involved Lockheed, a US aerospace company, and the bribing of officials in West Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Japan, all friendly US allies. Incidents like these and a shift in public sentiment led nations in the United States and Europe to review their ethical compass. As a result of these reviews, new laws in the late 1970s and 1980s were passed in the United States and Europe, placing the responsibility on companies to apply these new ethical views on their global operations with the threat of both corporate and personal liability for infringement.

The United States passed the foreign corrupt practices act (FCPA) that covered all US-based corporations and foreign ones operating in the United States. This shift could also be seen from the evolution of economic thinking about the role of the firm in the economy. Traditionally economists were focused on exploring the production function of the firm. Over the years, this changed to exploring the pre-production and postproduction activities as critical components of the value chain. Within this scrutiny came the realisation that boundaries between the many activities the firm engaged in were difficult to establish and, even more so, in the post-industrial age in which a knowledge-intensive and alliance environment drove the global economy. This, in turn, led scholars to question their focus on profit-maximising theories to focusing on more value-driven activities, which, good or bad, is an integral part of a firm’s competitive toolbox (Dunning 2003).

The idea is that as firms internationalise, management plays a central role in performing all the other functions other than routine production ones. The coordination of these activities requires both knowledge, expertise, decisions making, and it involves a trade-off of alternatives. This accumulated knowledge is internalised by a firm and utilised in foreign direct investments in subsequent expansions (Buckley and Casson 1976). All these decisions and experience must, by their very nature, also take into account each individual country’s mix of cultures, customs, values, and laws. Multinationals pre-1970 had little accountability and were expected to be able to be competitive, operate within the law, and, as much as possible, ethically. Although this last one, ethical behaviour, was dependent in no small measure on what the perceived value of a trade-off between success and ethics meant for its stakeholders. The imposition of specific laws that reflected the political views of ethics in a multinational's home nation at the time placed restrictions specifically on acts that were defined as corrupt. This definition of corruption was and is a matter of definition and enforcement. While acts such as the FCPA were aggressively enforced, in many ways, they were contradicted by some of the internal home market-accepted practices and laws. For example, in the United States, the creation of the political action committees (PACs) and the emergence of a powerful and well-funded lobbying industry have allowed companies to both get around political contributions and the direct influencing of politicians. If we follow both the externalities imposed on a firm and the need to internalise knowledge, which presumably would include ethical components, we can start to try to envision the inherent contradictions and dilemmas that managers may face as they expand into a larger number of new markets.

These dilemmas get amplified as words like corruption have different meanings and interpretations in other locations. As we discussed earlier in this chapter, the inherent difference from an eastern perspective where the value of the word given, and by implication an implicit commitment or contract, outweighs the actual deed that leads to it, such as a gift or favour.

Corruption is a result of sometimes vague ethical tribal or societal perspectives that result in a cultural centric political ideology. This ideology is then translated into laws and codes that, in some cases, define corruption as a criminal offence that can range from large payments to government officials to a small bribe to a low-level bureaucrat. According to Transparency UK, 73% of companies assessed in their ‘2018 Corporate Political Engagement Index’ (CPEI) received ratings between ‘fairly poor’ and ‘abysmal’ standards (Bands D-F) (Corporate Political Engagement Index 2018 2021). Some of the companies in this Index that scored lower in the CPEI were Amazon, AstraZeneca, Disney, Ford, Samsung, and Huawei (Begu et al. 2019). Bribery in international operations by western-based corporations was not always considered as an issue or morally wrong. Some companies even filed this type of bribery as an operating expense while doing business in emerging economies. For example, even as recently as the turn of the millennium, German corporate law punished bribery at home but considered it a standard practice when doing business in emerging economies (Rose-Ackerman 1997).

As mentioned earlier, attitudes towards bribery changed significantly in the United States, with a domino effect on most western nations. When the US Congress passed the FCPA in the late 1970s, this act made it illegal for American companies abroad to make briberies. Bribing to obtain a contract while competing against other companies became unlawful. However, there is a thin line when there is a bribe given to a low-level bureaucrat to speed up a process that will happen. Small payments are allowed in some countries because they can be rationalised as a top-up salary for the low-level officials that do this type of procedure. However, there is the question of what is a ‘small payment’.

Our central premise has been that cultural differences bring with them differences in definitions, interpretation, approaches, and laws. Following China's integration into global trade, the ethical status of guanxi, a practice where informal networks were integrated into the agreement and allowed companies and public officials to function as a transaction link (Luo 2008). Since there is not a specific payment, guanxi does not fit the traditional definition of bribery. It has been argued that the practice of guanxi is an unwritten contract, and a ‘quid pro quo’ is expected at some point in time. It is unclear to say if this constitutes an act of bribery or just a way of conducting business in China (Redding 2003). At the same time, existing methods of influencing outcomes regardless of how corruption is defined continue in many of the countries that have passed some of the most robust anti-corruption legislation. Volkswagen group, for example, although knowingly cheated by manipulating emissions in an elaborate scheme that included most layers of management. This included an understanding of secrecy and complicity and in which the German government's sub-rosa complicity may have ensured that the long-term effects were minimised. It is probably not a coincidence that the German State of Lower Saxony has a 20% voting share in Volkswagen, and because of a unique law, it has extra members on the board, thus ensuring ultimate control of the company (Elson et al. 2018).

Is There an Effective Treatment for Ethical Cancer?

The legalisation of ethical issues and those related to definitions around corruption through acts such as the FCPA and the Sarbanes–Oxley act of 2002 has been intended to address rule-based issues of corporate scandals. This has resulted in many companies implementing codes of ethics and appointing ethics officers and consultants. However, most of these initiatives have been rule-based. Corporations and the US government have looked at individuals to address the implementation of the law to ensure compliance. Even these legal attempts to quantify ethical behaviour have a very narrow definition and are more preoccupied with detecting ‘criminal conduct’ than broader ethical, civil rights, or other related issues (Michael 2006). Thus, the laws are more a reflection of a particular position of corruption, preferably that an attempt to include a broader view of ethical behaviour on corporations effectively. It could be that laws passed by political institutions that are frequently measured against a more Hellenic definition of the right character routinely fail against that measure may find it difficult to legislate into this broader view.

Politicians in both Germany and the United States that have been vocal with their anti-corruption stance and narrow legislation find themselves in situations that they themselves find difficult to explain or justify. For example, Gerard Schroeder, Germany’s former Chancellor, who negotiated and approved the gas pipeline between Russia and Germany, became chairman of the Russian gas and oil company Rosneft. The second example refers to the large oil service contracts Halliburton, a Texas-based oil service company, was awarded after the invasion of Iraq, considering that the then Vice president of the United States, Richard ‘Dick’ Cheney, had been the CEO of Halliburton prior to becoming Vice president. Both examples illustrate the constant contradictions faced by company executives as they are forced to impose laws that their own official seem to flaunt or, at the very least, clearly do not believe in the spirit of the ethical principles behind the laws.

A treatment for corruption is hard to create because, as Hess and Dunfee (2000, 608) clearly explained, when referring to bribery but applicable in other types of corruption, ‘there is a growing movement against the practices, yet there is no hard evidence that the level of corruption is declining- and it may even be increasing’. Firms aggressively seek to prevent the corruption of their own employees while simultaneously approve of attempts to corrupt the employees of potential suppliers. Firms from countries that have reputations for being relatively clear of corruption are thought to be significant sources of corruption in other countries. The most general and logical reason for failure to implement robust treatments for corrupt practices is the design and implementation problems, but some scholars have suggested that there are other deeper issues. Heeks and Mathisen (2012) add that failed anti-corruption initiatives have a wide gap between design and reality, and a wide gap leads to unsuccessful implementation. But most importantly, they argue, is the political situation that determines the success or failure of any initiative.

As we argued at the beginning of the chapter, the differences between eastern and western approaches to corruption are then made even clearer in the West as laws are passed to penalise corporation on perceived corruption practices with narrow definitions and ambiguous ethical principles behind them. However, and for the sake of clarity, we are not advocating for the wholesale pillaging of economies at one extreme of the corruption pendulum. The western definition that has been imposed on corporations through laws and enforcement defines corruption in such a broad way as not to allow local customs and ethical perspectives to be allowed within the purview of management's decision-making. It could be argued that this is but another form of cultural colonialism. It also leaves corporations in a complex competitive and moral position on the one side, forcing practices and ethical behaviours on other nations that their own home country politicians do not adhere to. The definition of what the word ‘corruption’ may have and its ethical implications at the other end of the pendulum may lead to delicate and subtle differences in levels of societal and cultural acceptance that another society may not know or care to understand. We do not argue for or against corruption, in its more extreme western sense, rather that, in a complex world stemming from different ethical perspectives and definitions, the resulting actions of those involved should be more balanced and inclusive.

The modern West has tried to have clear views on corporate and personal ethical behaviour, and corruption is a target that is shunned and regulated. As discussed earlier in this chapter, this western focus on targeting corruption in all its forms has been driven by scandals and led to the passage of the corrupt practices act. A criticism of the act has been that it is too restrictive and does not allow for legal and even less societal accepted practices in other nations. Hence, the claim is made that this is in effect nothing more than ethical neo-colonialism. As most societal driven attempts to regulate and codify moral and ethical behaviour find themselves later having to amend them as the tribe or society's point of view changes. The nearly absolute moral view that killing is wrong is quickly amended in times of war where the same behaviour is encouraged, rewarded, and glorified. In the same manner, the US corrupt practices act has many detractors. Former President Trump, reflecting society's (or his own on society) adjusted ethic compass during his presidency, is quoted as saying, ‘it’s just so unfair that American companies aren’t allowed to pay bribes to get business overseas’ and indicated he wanted to scrap it (Smialek 2020). The long-held view on the other side of this pendulum by many academics and politicians is that corruption in any form is detrimental to society and by extension to the individual. Corruption is harmful to the growth prospects of host countries and can introduce inefficiencies and inequities. Rose-Ackerman (2002, 1889) argues that ‘business corporations have an obligation to refrain from illegal payoffs as part of the quid pro quo implied by the laws that permit corporations to exist and to operate’. Jurkiewicz (2020, 151) explores the individual ethical choices and ascertains that ‘collectively, corruptive behaviour causes societal harm and lessens the credibility of public organisations in conducting business, such as tax collection, citizen/government interactions, and judicial oversight, and reduces trust in government’. Further, it can cause environmental damage (Cole 2007), increase costs, and depress economic development (Dearmon and Grier 2011). As in much of this debate and opposing views, corporations find themselves in the middle on the one side trying to reduce their liability of foreignness, compete domestically and/or globally with other companies with different ethical views, be a good corporate citizen in its home and host nations and deliver to all its stakeholders’ behaviours, practices, and profits that satisfies them all.

Also, the pendulum swings that brings with it political changes and resulting laxed or harsher implementation of the laws, perceptions, and activities in the home nation that is there for everyone to see. The swings recently to populism and the self-enrichment of politicians in the United States, Brazil, Hungary, and the Philippines add to the dilemmas faced by western corporations. Eastern-based firms may have seen some slow changes to some norms and face a much less disruptive environment at home where political change usually does not bring the radical shift in perception towards ethics, corruption, and the ‘way of doing things’. We argue for a less intrusive and legalised view of practices and enforcement that allows for ethical positioning and definitions of matters such as corruption to be fragmented and acted upon based on custom and common sense. Managers, entrepreneurs, and even politicians are better served in general to be allowed to act within their own environments in a way that serves their people and institutions best.

References

Arjoon, Surendra. 2017. “Virtues, Compliance, and Integrity: A Corporate Governance Perspective”. In International Handbooks in Business Ethics, 995–1002. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Barcham, Manuhuia. 2012. “Rule by Natural Reason: Late Medieval and Early Renaissance Conceptions of Political Corruption”. In Corruption: Expanding the Focus. ANU Press.

Basu, Kaushik, and Tito Cordella, eds. 2018. Institutions, Governance and the Control of Corruption. 1st ed. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Begu, L.S., S.A. Apostu, and A.O. Enache. 2019. “Corruption Perceptions Index and Economic Development of the Country”. Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Statistics (Sciendo) 1 (1): 115–22.

Belfort, Jordan. 2011. Catching the Wolf of Wall Street: More Incredible True Stories of Fortunes, Schemes, Parties, and Prison. New York, NY, USA: Bantam Books.

Botton, Alain de. 2008. The Consolations of Philosophy. Harlow: Penguin Books.

Buckley, Peter J., and Mark Casson. 1976. “The Multinational Enterprise in the World Economy”. In The Future of the Multinational Enterprise, 1–31. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Coates, A. J. 1997. The Ethics of War. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Cole, P. 2007. “Human Rights and the National Interest: Migrants, Healthcare and Social Justice”. Journal of Medical Ethics 33 (5): 269–272.

Corporate Political Engagement Index 2018. 2021. Org.Uk. Accessed June 16. https://www.transparency.org.uk/cpei/.

Dearmon, J., and R. Grier. 2011. “Trust and the Accumulation of Physical and Human Capital”. European Journal of Political Economy 27 (3): 507–519.

Denoon, Donald. 2009. A Trading Network and Its South African Node—Networks of Empire: Forced Migration in the Dutch East India Company, Xv+340. By Kerry Ward. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hardback (ISBN 978-0-521-88586-7). Journal of African History 50 (3): 457–58.

Dimanti, Eugen, and Guglielmo Tosato. 2018. “Causes and Effects of Corruption: What Has Past Decade’s Empirical Research Taught Us? A Survey: Causes and Effects of Corruption”. Journal of Economic Surveys 32 (2): 335–56.

Duiker, William J., and Jackson J. Spielvogel. 2010. The Essential World History: V. 1. Belmont, CA, USA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Duiker, William J. Duiker, and Jackson J. Spielvogel. 1994. World History, Volume I to 1800. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Dunning, John H. 2003. “Some Antecedents of Internalization Theory”. Journal of International Business Studies 34 (2): 108–15.

Elson, Peter R., Jean-Marc Fontan, Sylvain Lefèvre, and James Stauch. 2018. “Foundations in Canada: A Comparative Perspective”. The American Behavioral Scientist 62 (13): 1777–1802.

Gaustad, Edwin S., and John T. Noonan Join. 1988. “The Believer and the Powers That Are: Cases, History, and Other Data Bearing on the Relation of Religion and Government”. Journal of American History (Bloomington, Ind.) 75 (1): 226.

Gustafson, Andrew. 2013. “In Defense of a Utilitarian Business Ethic: Business and Society Review”. Business and Society Review 118 (3): 325–60.

Hammurabi. 2018. The Code of Hammurabi: (Annotated)(Illustrated). Edited by Jan Oliveira. Translated by Robert Francis Harper. Independently Published.

Hauser, Marc, and Peter Singer. 2005. “Morality Without Religion”. Free Inquiry 26: 18–19.

Heeks, Richard, and Harald Mathisen. 2012. “Understanding Success and Failure of Anti-Corruption Initiatives”. Crime, Law, and Social Change 58 (5): 533–49.

Hess, David, and Thomas W. Dunfee. 2000. “Fighting Corruption: A Principled Approach: The C Principles (Combating Corruption)”. Cornell International Law Journal 33 (3): 593–626.

Hitka, Miloš, Milota Vetráková, Žaneta Balážová, and Zuzana Danihelová. 2015. “Corporate Culture as a Tool for Competitiveness Improvement”. Procedia Economics and Finance 34: 27–34.

Hodder, Ian. 2012. Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships Between Humans and Things. 1st ed. Chichester: Wiley.

Huttenback, Robert A. 2003. Kashmir and the British Raj 1847–1947. Karachi, Pakistan: OUP.

Imran, Syed Muhammad, Hafeez Ur Rehman, and Rana Ejaz Ali Khan. 2019. “Determinants of Corruption and Its Impact on Firm Performance: Global Evidence”. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences 13 (4): 1017–28.

Jacques, Scott, and Richard Wright. 2010. “Right or Wrong? Toward a Theory of IRBs’ (Dis)Approval of Research”. Journal of Criminal Justice Education 21 (1): 42–59.

Johnson, Noel D., William Ruger, Jason Sorens, and Steven Yamarik. 2014. “Corruption, Regulation, and Growth: An Empirical Study of the United States”. Economics of Governance 15 (1): 51–69.

Jurkiewicz, Carole L. 2020. “The Ethinomics of Corruption”. In Global Corruption and Ethics Management: Translating Theory into Action. Rowman & Littlefield. https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781538117415/Global-Corruption-and-Ethics-Management-Translating-Theory-into-Action.

Keefer, Bradley S. 2013. Conflicting Memories on the “River of Death”: The Chickamauga Battlefield and the Spanish-American War, 1863–1933. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press.

Kurer, Oskar. 1993. “Clientelism, Corruption, and the Allocation of Resources”. Public Choice 77 (2): 259–73.

Leff, Nathaniel H. 1964. “Economic Development Through Bureaucratic Corruption”. The American Behavioral Scientist 8 (3): 8–14.

Lewis, N., 1954. “On Official Corruption in Roman Egypt: The Edict of Vergilius Capito”. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 98 (2): 153–58.

Leys, Colin. 1965. “What Is The Problem About Corruption?” The Journal of Modern African Studies 3 (2): 215–30.

Luo, Yadong. 2008. “The Changing Chinese Culture and Business Behavior: The Perspective of Intertwinement Between Guanxi and Corruption”. International Business Review (Oxford, England) 17 (2): 188–93.

Martins, Lurdes, Jorge Cerdeira, and Aurora Teixeira. 2020. “Does Corruption Boost or Harm Firms’ Performance in Developing and Emerging Economies? A Firm‐Level Study”. World Economy 43 (8): 2119–52.

Méon, Pierre-Guillaume, and Laurent Weill. 2010. “Is Corruption an Efficient Grease?” World Development 38 (3): 244–59.

Michael, Michael L. 2006. “Business Ethics: The Law of Rules”. Business Ethics Quarterly: The Journal of the Society for Business Ethics 16 (4): 475–504.

Mill, John Stuart. 1998. Utilitarianism. London: Oxford University Press.