Abstract

The study investigated two expert writing teachers’ feedback and assessment practices and their emic (insider) perspectives on factors impacting on those practices. Specifically, the teachers shared their expertise knowledge and skill in dealing with formative assessment. Data were collected at a distinguished university in Northeast China over a 17-week semester through written texts, interviews, think-aloud and stimulated recalls. The study identified multiple factors influencing the teachers’ feedback choices. The first notable factor was the two teachers’ belief in the value of multiple drafts on a regular basis. The second factor was their belief in peer review. To apply peer review effectively among Chinese writing students, they provided systematic sustained support and supervision for peer reviewers. Another important factor guiding their feedback choices was the alignment between writing assessment rubrics and class instructional focal points. The two teachers treated feedback on paper not as an isolated act but as part of the teaching cycle. Teacher feedback and teacher assessment were not only to reflect but also to inform instruction.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

1.1 Motivation for the Study

One major motivation for the study arose from the observation that in the teacher feedback research, teachers’ own voice was not often heard. An in-depth understanding of teachers’ knowledge and beliefs underlying their actual practices can lead to a fuller and more valid conceptualization of teaching, rather than a superficial behavioral representation of teaching (Borg, 2006). The value of understanding the mental side of teachers’ work is that insightful information gained from research can be put to effective use in teacher education and development programs by encouraging teachers to develop their personal systems of knowledge, beliefs, and understandings drawn from their practical experiences of teaching (Freeman, 2002; Freeman & Richards, 1996; Richards, 2010). In her investigation into distinctive qualities of expert teachers, Tsui (2009: 429) found that one key quality of expert teachers is that they are capable of theorizing practical knowledge (i.e., “making explicit the tacit knowledge that is gained from experience”) and practicalizing theoretical knowledge (i.e., “making personal interpretations of formal knowledge, through teachers’ own practice in their specific contexts of work”). Important as they are, there is limited research on the actual processes of writing instruction and teacher feedback as perceived by writing teachers themselves (Ferris et al., 2011; Goldstein, 2005). Meanwhile, inferences are frequently made about teachers’ intentions to employ particular feedback strategies without consulting the teachers themselves. This is problematic because no matter how well researchers may know the teachers, their assumptions may be incorrect (Ferris, 2014; Ferris et al., 2011; Goldstein, 2001, 2005).

1.2 Context of the Study

This study is also intended to address a practical concern of Chinese EFL writing teachers. Studies on teacher knowledge and beliefs about feedback, very limited in number, have been largely conducted in ESL contexts. Little relevant research has been conducted so far in EFL contexts such as mainland China. This consideration of language education contexts is important because findings of research conducted in ESL contexts may not be applicable to the EFL context of mainland China, given its unique English writing curricula, assessments, and pedagogical approaches.

English teachers in mainland China seem to face several obstacles when teaching writing in college English classes. Insofar as approaches to teaching English writing are concerned, although process-oriented writing has been imported and encouraged, pre-writing and multiple-drafting activities have appeared, and concepts of peer review and portfolio assessment are being tested out in classrooms, the traditional product-based pedagogy still dominates the majority of writing classes at universities in mainland China (Mei & Yuan, 2010; You, 2004b; Zhang, 2005). This pedagogy, typical of many Chinese universities (see Wang, 2010), is problematic because in product-oriented classrooms teacher feedback tends not to be taken seriously when revision is not required (Ferris, 2003; Hyland & Hyland, 2006). Moreover, college English teachers carry the heavy burdens incurred by the large college enrollment expansion. For most writing teachers, one of the burdens is to give feedback to writing submitted by a large class of students (Wei & Chen, 2003; Yang et al., 2006).

1.3 Factors on Feedback Choices

Factors contributing to a predominant product-oriented feedback and assessment approach include the local culture of education (see Hu, 2002; Yu et al., 2016, for more about Chinese culture of learning), test-oriented teaching (see Pan & Block, 2011, for a detailed illustration of the “put exams first” view), and big class size (You, 2004a, b). The rapid expansion of Chinese higher education at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels has resulted in rising class sizes that pose a number of challenges to English teachers (Jin & Cortazzi, 2006). This is confirmed in Du’s (2012) interviews with the Heads of English Departments from three Chinese top-tier universities, who reported class sizes ranging between 40 and 90 students.

Two studies (i.e., Yang, 2010; Zhang, 2008) with their particular focus on the beliefs of English writing teachers in mainland China are worthy of special attention. In terms of the relationship between writing teachers’ beliefs and practices, the two studies came up with different findings. Zhang (2008) explored in a qualitative case study the beliefs and practices of five university English writing teachers who taught non-English major students. The study found teachers believed that writing was a complicated cognitive process and that teachers should design and use communicative activities like group discussion and peer feedback. However, observation data demonstrated that these beliefs were not accordingly enacted in class or in feedback.

Complementing Zhang’s study with writing teachers in a middle-ranking university, the second study by Yang (2010) focused primarily on beliefs and practices of three writing teachers in an elite university, who taught both English and non-English major students. The study found that all the teachers believed that writing was a thinking process and that both language use and the development of thinking skills were key goals of writing instruction. But, different from Zhang’s (2008) findings about the inconsistent relationship between beliefs and practices, Yang’s study found that the three teachers all emphasized a balance of writing products and processes in their beliefs and their practices.

First, the conflicting findings might have to do with the different learning and teaching experiences of the participant teachers in the two studies. The three teachers in Yang’s study had many years of English teaching experience (i.e., 15, 23, and 43 years, respectively) and writing instruction (i.e., 5, 12, and 15 years, respectively). Two of them had completed postgraduate studies in the US and worked as teaching assistants for writing courses in the US universities. Their overseas learning and working experiences had a great impact on their perceptions of the value of process writing and prepared them well for the implementation of the approach. In contrast, the five teachers in Zhang’s study had less teaching experience (i.e., 2, 7, 8, 10, and 23 years, respectively). Even though no details about their experience of teaching writing were provided, the researcher indicated that those teachers were inexperienced in teaching writing and unfamiliar with the nature of the process-based pedagogical approach. It has been suggested in the literature that more experienced teachers are likely to have more experientially-informed beliefs than less experienced teachers, and that deeply held principles or beliefs informed by teaching experiences might be applied more consistently to teaching practices than principles acquired from teacher education (as it is expected in the case of new teachers) (Basturkmen, 2012; Breen et al., 2001).

Second, the conflicting findings of the two studies might have to do with the significant institutional differences existing between the elite university in Yang’s study and the middle-ranking university in Zhang’s study. The former university’s students, less influenced by the prospect of tests since the passing rate of the tests (i.e., College English Test and Test for English Majors, CET and TEM in short) had remained high for a considerable time, welcomed the development of their writing skills more than enhancing their test taking skills. In addition, the class size at the elite university was around 24. In contrast, students from the latter middle-ranking university were more CET oriented and studied English in a bigger class. Therefore, teachers in the elite university had relatively favorable conditions for adopting pedagogical activities such as multiple drafts, multiple revisions, and peer feedback.

It is recommended in the literature that feedback should be provided on multiple drafts (not only final graded drafts) and from multiple sources (not only teachers) (Ferris, 2014; Lee, 2017). Peer review, as a prominent feature of process-oriented writing instruction, has many potential benefits (Huisman et al., 2018; Hyland & Hyland, 2006; Tsui & Ng, 2000; Zhang & Mceneaney, 2019). In spite of certain advantages of peer review, it is “not readily embraced by teachers in L2 school contexts” (Lee, 2017: 98). In the context of mainland China, two reasons evident in Zhang’s (2008) study may account for the limited use of peer feedback: one, teachers’ unfamiliarity with the nature and value of peer review; two, teachers’ perception of contextual constraints they have to deal with when it comes to the implementation of peer review. While the bulk of peer review studies investigated students’ perceptions and attitudes (Chang, 2016), studies that look at writing teachers’ perceptions and attitudes are still scarce.

In response to these issues, there are calls for more research that can take account of teachers’ practitioner knowledge about formative feedback in specific teaching contexts. The present study, therefore, investigated two expert writing teachers who implemented their ideal feedback practices (e.g., multiple drafts, peer review, self-assessment) despite constraints that seem get in the way in other teachers’ attempts to do so in the EFL context of mainland China. The study incorporated the teachers’ own voice to address the “how” and “why” questions: How do the teachers give feedback? More importantly, why do they give feedback in the ways they do?

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and Teaching Context

The study is part of a large research project on feedback practices and beliefs of Chinese university EFL writing teachers. The large research project adopted a mixed-methods design: a qualitative multiple-case study of 10 teachers and a quantitative questionnaire survey (N = 202). The case study in the first phase investigated teachers at a distinguished university in Northeast China. Purposeful and snowball sampling was adopted. Teaching experience was the major consideration in recruiting participants. Among the 10 teachers, two teachers taught English writing for over 10 years and three teachers less than 2 years. Teachers who taught English majors and those taught non-English majors were both recruited. For the purposes of identifying the potential impact of personal learning/training and research experiences, special effort was also made to recruit teachers who had overseas learning/training experiences and those who did not, and teachers who had research interests in EFL writing instruction and those who did not.

The study reported in this paper focused on two female teachers Anna and Bella (pseudonyms) who taught English major students in the School of English Studies. Anna, the former writing course coordinator in the school, had 11 years of experience teaching English writing, and was also one of the staff that had led a writing pedagogy reform in the school since 2006. As a result of the reform lasting many years, the product approach to writing that had been dominant in the school was replaced by the process-genre approach (see Badger & White, 2000). At the time of the study, Anna was doing a research project on formative assessment in EFL writing instruction and had already published extensively in that area. Bella was the current course coordinator. She had taught English writing for 8 years. She obtained a PhD degree in Applied Linguistics, and her research area was teacher feedback. Anna and Bella were both considered by their colleagues not only as experienced teachers but also expert teachers in writing instruction. They were called ‘backbone’ writing teachers in the school. Their expertise was manifested in their mentoring of novice writing teachers, their knowledge of writing pedagogical approaches, their engagement in the writing pedagogy reform, and their publications in the field of writing instruction.

Generally speaking, their writing instruction was devoted to teaching English major sophomores how to write argumentative essays and notes – two types of writing tasks tested in TEM-4. There were 24 students in Anna’s class and 35 students in Bella’s. The average class size was 30 students in the school. Assessment was based on students’ performance in weekly writing tasks (75% in total) and an end-of-semester project (25%). It was not mandated how teachers should go about responding to student writing. None of the course documents specified guidelines teachers should follow in marking student written texts, except that each semester teachers should select a minimum of three compositions by each student to comment on and grade. The scores given for the three compositions would be added to account for a great proportion (75%) of the final assessment of student writing performance. Apart from the minimal feedback workload required, there was no mention of feedback criteria in any course document. Peer feedback and multiple drafts were not compulsory. In other words, teachers had complete freedom and flexibility in terms of giving feedback to student writing.

2.2 Instruments

Multiple instruments were used to collect data from the participants. First, teacher interviews elicited data about participants’ self-reported practices, rationales for the practices, and relevant personal experiences. The interviews conducted in the case study were semi-structured, and most questions were open-ended in nature. The interviews were conducted in Chinese. I translated all the interview data from Chinese to English. Second, think-aloud provided data about teachers’ decision-making and thought processes while they were giving feedback. Third, stimulated recall sessions focused on how teachers explained and justified their specific feedback strategies. Last but not the least, marked student texts with teacher feedback elicited data about teachers’ actual feedback practices. Collectively, these instruments were intended to create maximal opportunities for the teachers to speak for themselves. They were also aimed to achieve data triangulation, providing corroborating evidence from different sources to shed light on the research questions (Barnard & Burns, 2012; Miles et al., 2014).

In addition, student texts with peer feedback were also collected and two student interviews conducted. These additional data were collected because, in the midst of data collection, it was found that the two teachers, unlike other teachers in the case study from the same school, frequently used peer review. This discovery led quickly to a modification to the research design. It is worth noting that all the written peer feedback was not generated for the study’s purposes but was naturalistic data.

2.3 Data Collection and Analysis

Table 12.1 provides details of data collection procedures. I met the teachers three times spaced out over a 17-week semester (i.e., meetings with Anna in weeks 2, 8 and 13 and Bella in weeks 3, 8 and 15). Considering the teachers’ busy work schedules and preferences for online communication, they were further contacted mainly via the university’s Office Application system or the networking app WeChat. Whenever it was necessary for them to add on, confirm, or clarify the interview data, they would be contacted.

As for the collection of student texts, students were invited to provide their assignments that had already been marked up by their teachers for any task. The specific procedures were as follows: Immediately after a teacher agreed to participate, I went on to contact one student in the teacher’s class (either the class monitor or the subject representative) and sought his/her help to promote the study among the students. The student was then asked to help collect his/her classmates’ texts that had been written by Week 6 and Week 14. This method of seeking students’ help for text collection was suggested by a participant teacher. She suggested that it would be more feasible to ask the student representative rather than the busy teachers to collect student texts and ask students to sign a consent form if they agreed to participate.

Coding of the data was conducted using NVivo 10. Altogether, the interview data were coded in three cycles. The first cycle was to establish a list of open codes (Saldana, 2000). The coding unit was set as a single sentence, but extended to a whole paragraph for the majority of the texts. Each unit in the text was assigned one or multiple code names, using either words in vivo (i.e., words or short phrases taken from the participants’ own language), a descriptive label, or a concept in the literature (Saldana, 2000). The second cycle was to generate pattern codes. The main purpose was to chunk and sort data into categories. Three overarching categories were (a) self-reported feedback practices, (b) rationales (knowledge, belief, view), and (c) relevant teaching experience. The sub-categories under each overarching category were not pre-designed but mostly emerged from the interview data. The third cycle was also to generate pattern codes. However, different from the second cycle, it aimed to establish pattern codes that could reflect “relationships among people” (Saldana, 2000: 88). Specifically, cross-case comparison was made to identify similar and different self-reported feedback behaviors and beliefs among the 10 teachers in the large study. I composed a summative narrative (one or two pages long) for each teacher in order to achieve a comprehensive understanding of their distinctive feedback practices. I also drew up a cognitive map for each teacher to visually display their networks of beliefs and knowledge.

The teachers’ actual written feedback on the student written texts was coded using NVivo 10, too. The coding started with the identification of feedback points. Counting feedback points is the most widely adopted method in the textual analysis of teacher written feedback (e.g., Lee, 2011; Montgomery & Baker, 2007). A feedback point refers to any mark, correction, or comment made by teachers that constitutes a meaningful unit. Each feedback point was then categorized in terms of feedback focus, error correction strategy, and feedback type, with reference to existing schemes in the literature (e.g., Hyland & Hyland, 2006; Lee, 2008).

To enhance the trustworthiness of the data analysis, the results of the preliminary analyses were sent back to the participants for clarification and confirmation that the results matched their interpretations.

3 Findings

The study identified multiple factors influencing the teachers’ feedback choices. The first noticeable factor was the two teachers’ belief in the value of peer review of multiple drafts on a regular basis. Peer review was frequently and extensively used by the two teachers and was a priority focus of their feedback. Another factor was their belief in the alignment between writing assessment rubrics and class instructional focal points. Teacher feedback and teacher assessment was not only intended to reflect but also to inform instruction. Last but not least, they believed that successful peer feedback relied on systematic sustained support and supervision on the teachers’ part.

3.1 Frequent Use of Multiple Drafting and Peer Review Liberates Teacher Feedback from Primary Focus on Linguistic Errors

The cross-case comparison in the large case study found that Anna and Bella contrasted sharply with other teachers in the same school and the teachers in other schools of the university. Those teachers did not use peer feedback at all or used peer feedback only once or twice in the semester. Anna and Bella, however, used peer feedback frequently and extensively throughout the semester. Anna organized peer feedback on a regular bi-weekly basis. Within these 2 weeks, her students were encouraged to produce as many drafts as possible based on feedback from peers. Peer feedback was conducted within groups of three or four who were usually roommates. Each student read and commented for the other two or three members of the group. Among the 14 student texts with teacher feedback collected from Anna’s students, six texts were third drafts, two texts fourth drafts, and two texts fifth drafts.

Anna confessed that, even though she told her students that every draft mattered in the final grade of one writing task, she could not afford time to examine the corrections and revisions in detail in every draft. But she did take the number of drafts and the “first-final-draft-difference” into consideration. That is, the more efforts a student put into revision, the higher grade would be awarded.

Individuals make their best efforts; peers also do their best. The fifth draft, the tenth one, I don’t set the limits. I ask them to submit all the drafts and bind them in order, with the first draft put at the bottom and the final one on the top, all labeled in number. (Anna, first interview)

The student interviews confirmed Anna’s reported practice of using peer feedback. They also gave evidence for Anna’s encouragement for additional revisions.

Sometimes when the final drafts are handed back to us, I will go on to revise. Topic sentences, concluding sentences, and coherence issues in between, we are asked to give another check at all these important points. (Anna’s student, interview)

The peer feedback of Anna’s students featured a focus on content and organization. For example, a classification essay on Different Types of Shoppers went through five drafts in total. Here are the comments from three peer reviewers. Originally, the peer comments were in English mixed with Chinese. I translated them into English.

- Reviewer 1::

-

The first paragraph does not exhibit the topic explicitly. For a classification essay, you had better come up with a theme running through the whole essay.

- Reviewer 2::

-

The classification does not follow one consistent standard. My suggestion: 1st type of shoppers buy just for need; 2nd type buy whatever they like; 3rd type do not buy anything.

- Reviewer 3::

-

Classification is good; three types are just alright, no more no less. The second type is inadequately discussed. Please elaborate. Sentence structures are somewhat simple.

It is very obvious that the peer editors had pointed out many issues in relation to content and organization: lack of clarity and controlling ideas in the topic sentence, inconsistent classification standards, and inadequacy of one supporting detail, etc.

Similarly, Bella told her students that she would check all the drafts and wanted to see “the original and the raw stuff – the true process.” Slightly different from Anna’s requirement of group peer review (i.e., three students reviewing one text, each student reviewing three times), Bella required her students to review in pairs. Another difference was that Bella required them to write down self summaries of their revision work. She checked on those self summaries and included them as the priority of her feedback focus. More accurately, her feedback started off with reading these self summaries and peer editors’ comments in reference to student texts. Her think-aloud data provided evidence supporting what she said. Bella started off her think-aloud like this, “This is news report… . This is the second draft. I read the peer comment first.”

The two teachers perceived peer review as effective but did not take it as a panacea. They acknowledged that they were aware that there would still be errors undetected in spite of peer correction, there would even be wrong corrections at times, and there would be good peer comments that were not appreciated. Despite their awareness of the issues surrounding peer feedback, both teachers strongly believed that peer feedback would be effective and helpful as long as adequate training, guidance and supervision were provided, another interesting finding to which Sect. 12.3.3 will attend in detail.

3.2 Teacher Feedback Not Only Reflects But Also Informs Instruction

The instructional objectives of Intermediate English Writing were to introduce the writing of a three-paragraph essay (opening paragraph, body paragraph and concluding paragraph) and to provide students with vocabulary, structures and techniques they would need in order to write four types of essays (exemplification, classification, cause and effect, and comparison and contrast). Moreover, topic sentences, concluding sentences, and transitional devices for the four types of essays were among the important instructional points focused on throughout the semester.

The two expert teachers gave their primary attention in feedback to issues that corresponded to their focal instructional points in class. The writing task that was assigned afterwards must relate to the points, so as to check whether students had grasped the teaching content and were able to apply what they learned in class to the actual writing.

The feedback foci were not absolutely fixed but varied in accordance with the lesson foci. The teachers shared that instructional focal points could be a particular genre feature or a type of student problem teachers wanted to address urgently. For example, apart from the regular lesson foci such as topic sentences, concluding sentences, and transitional devices, Anna and Bella both reported that they would set aside about two teaching weeks for intensive sessions targeting at sentence-level errors only, a focused issue they perceived necessary to address urgently. As they provided short-term intensive training to tackle students’ grammar errors, accordingly they gave special attention to language errors in the following one or two tasks after the training sessions.

The alignment between instructional foci and feedback foci was mainly achieved via the use of checklists. The two teachers reported that checklists were frequently emphasized and used in their class and also referred to in their feedback. For example, Bella used checklists to let the students know in advance what they should attend to in a news story. If students did well for the point(s), she would give a pass; but if students do not fulfill the requirement concerning the focal point(s), it would still be a definite fail, despite other appropriate aspects of the writing. Teacher assessment was based on their selective feedback on focal issues.

The alignment between class instruction and teacher feedback is a two-way process. The two teachers did not see feedback on paper as an isolated act but as part of the teaching cycle guided by the preceding instruction and preparing for the subsequent instruction. The excerpt below provides an example.

This student didn’t know how to use the transitional phrase ‘on one hand, on the other hand’. This is not a problem in her essay only. She might think this phrase can be used for listing out two things. She might not know that the phrase should be used for two different aspects of the same thing. I will explain it again in class. (Anna, second interview)

Figure 12.1 illustrates the teachers’ perception of the relationship between teacher feedback and class instruction. The two arrows on the top indicate the teachers’ perception of feedback as being “guided” by, and a natural extension of, class instruction. The two arrows at the bottom indicate that while the important points these teachers emphasized in class had found their ways into their feedback process, the problems they identified during the feedback “informed” them of what issues they should address in class.

3.3 Systematic Sustained Support and Supervision Is Important

3.3.1 Systematic Peer Feedback Is Aided But Not Restricted by Checklists

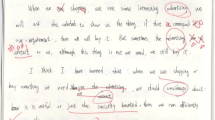

Anna reported that she trained her students to do peer feedback by referring to checklists. The checklists, in her words, served as “a blue print.” She emphasized that checklists can help reduce the subjectivity in feedback and the students need them as guidance. Otherwise, they would have no idea how to respond to peers’ work appropriately, as illustrated in the following excerpt:

I observe that what is characteristic of my students in peer review is they rush to look for grammatical and mechanical mistakes, circle them, and consider the job done. I remind my students that marking out mistakes and errors should be the very last thing to do in peer review. (Anna, first interview)

Anna suggested to her students that peer editors should mainly choose and cover global issues. She asked them to refer to the rubrics in the checklists, which were intended to give them reliable and appropriate guidance on what issues to look at. Figure 12.2 is one checklist Anna used for peer review of classification essays.

The two teachers explained that peer review should be based on, but not restricted by, the rubrics specified in the checklists. Originally, Anna had asked her students to put ticks/crosses on the lists. For a couple of tasks she had requested the students to print out checklists and attach them to the submitted compositions. Anna explained that the writing teachers in the university she visited in the US mostly ticked or crossed items on checklists; they seldom gave corrections or comments on students’ compositions. She had intended to keep to the same practice but gave it up because she observed that, more often than not, ticks/crosses on the list could not effectively reflect and monitor the students’ efforts in peer feedback. She recalled an experience to illustrate her point:

I once provided a checklist about paragraph writing to students. One student ticked high grades for many items for a paragraph written by his peer, but I read through the paragraph and found instantly it didn’t deserve the high grades. Based on my experience, I ruled out the possibility that the student editor was unable to find out the problems with that paragraph.

That is why she decided to modify the use of checklists, asking her students to put down specific textual comments because she believed it would push them to be more committed. They should not only give in-text corrections but also put down their comments at the bottom of the composition, either in English or Chinese. The comments should not cover every issue but focus on major issues regarding content, viewpoints and structures. The summative comments should fall into three categories: strengths, weaknesses, and suggestions. She explained that in this way written feedback became more focused, constructive and flexible; comments could cater to students’ individual problems.

3.3.2 Sustained Peer Review Support Is Achieved Through Regular Dialogues and Discussions in Class

Anna preferred to give support for peer feedback in class. Anna found that it was necessary for her to model for the students the review process and to follow up by reviewing one or two tasks together with them. More importantly, it was necessary to sustain discussions about peer performance in class whenever necessary. Even though checklists served as the guidance, class discussion activities must follow up so as to check whether students applied the rubrics to the actual peer feedback accurately and objectively.

Anna requested her students to give oral presentations of peer feedback in class. There were three specific procedures. First, peer feedback was done within groups. Second, each group decided on one composition for presentation in the second session. Anna gave three selection criteria. They could choose (1) the one they agreed to be the best written, (2) the one with the biggest improvement when compared to the first draft, or (3) the one that all members in the group had no idea how to help to improve, that is, with problems that they felt incapable of dealing with. Third, in the second session each group presented the selected essay together with peer comments. Afterwards, Anna and the student audience would give further assistance and guidance, working together with the groups to comment on the selected essays.

Anna observed that when it came to topic sentences, peer editors were likely to fail to provide effective evaluation. It happened often that her students thought a composition had an effective topic sentence, whereas actually she later found out that the topic sentence was either just a statement of a fact (but not the writer’s opinion) or a statement that contains a topic (without controlling ideas that the following sentences can support or prove). The same was true of the supporting details. Under these circumstances, she would follow up to point out in class what was wrong with the peer comments. The student interview confirmed Anna’s self-reported practice.

What to focus on in peer review? At the beginning we didn’t know, only to mark out small grammar mistakes. Later, Miss Anna taught us to focus on global issues like organization and selection of supporting details. She gave a lot of emphasis on these two aspects. One time, girls in my dormitory chose one essay we all thought were well-written, the one we could not perfect any more. It turned out, however, that when we put it on the ppt slide in class, Miss Anna detected a problem with supporting details, which we didn’t notice previously. There are situations like this: we all believed an essay was good enough, but when Miss Anna pointed out the issues, we were kind of taken aback, “indeed, there were problems.” We are not having as sharp eyes (as the teacher). (Anna’s student, interview)

Apart from the group presentation of peer comments in the second session, Anna believed the conferencing in the subsequent session was also necessary in that it could allow her to check the students’ uptake of those suggestions derived from the class discussion. Here is an example.

One time, a student, already in the middle of the semester, didn’t recognize run-on sentences in his writing… . It just happened that his essay was selected by his peer editing group as the representative sample for presentation in the second session. I of course pointed out that he had written run-on sentences. However, he didn’t correct them in his revision. When the final draft was collected for me to grade, I was surprised that the problem was still there. Then I pointed out this problem in the fourth session to the whole class again. That student kind of protested, “Miss Anna, I have been writing sentences like that since long ago. How come they are wrong?” I then realized that he was not aware what a run-on sentence was. I wrote his problem sentence on the blackboard and the whole class analyzed and discussed it again. The other students confirmed to him that it was indeed a mistake. (Anna, first interview)

On reflection, Anna realized that “a mistake, if repeated, becomes a false truth. This is a good lesson for both that student and the rest of the class.” She also realized that because of their low language proficiency, follow-up class discussions were much needed to assist and evaluate the peer feedback performance and monitor the uptake of peer/teacher comments.

3.3.3 Supervision of Peer Feedback Is Read and Monitored Regularly on Written Texts

While Anna worked together with her students on peer feedback in class, Bella preferred to give further written comments on peer commentary and required her students to write reflective self-editing summaries. She reported that after one or two sessions teaching her students about how to do peer review, more importantly, she needed to keep “pushing” or “monitoring” the students to do peer feedback by various means.

Bella would read peer feedback and make comments next to it, like “He (peer editor) gave good comments,” “very to the point,” and “good suggestions.” She also required her students to submit their second drafts with reflective summaries of revisions and to indicate in the summaries where they took up peer comments.

The student editors, I know, usually would check if the teacher responded to their comments, and if the teacher approved of their comments. I feel only when I attended to the peer performance this time, could they carefully do peer review next time, because they knew not only the student writer would read (their comments), but the teacher too… . Peer feedback requires student commitment. Only when they feel like doing, willingly and carefully, could it be a practice that improves their skills. (Bella, first interview)

Additionally, Bella used grades to incentivize peer and self editing.

I told students that the peer review and self reflection were part of evaluation. I said that merely with the intention to push them. If student A edited for B, I asked A to put down his/her name. Just wanted to push them but didn’t actually grade peer comments. If I had really counted it as part of the final assessment, it would have been too complicated and troublesome. (Bella, second interview)

4 Discussion

The study identified three pedagogical factors behind the teachers’ feedback choices: multiple drafts, peer feedback and feedback foci alignment with the learning goals of instruction. In what follows, the feedback practices of the two teachers in the present study are discussed and compared with practices recommended by feedback literature.

Previous peer feedback studies of Chinese students mostly investigated its effectiveness in comparison with teacher feedback in an experimental design and students’ perceptions of its effectiveness (e.g., Hu & Lam, 2010; Hu & Ren, 2012). Previous studies have also reported the difficulty of using peer review (e.g., Hu, 2005; Hu & Lam, 2010; Yu et al., 2016) and multiple drafts (e.g., Wang, 2010) among Chinese students. There was a wide difference in teachers’ beliefs about peer review. These varied beliefs centered on three questions: whether students that grow up with Chinese learning cultures are capable of doing peer review, what contributions it can make to student writing, and whether it can be implemented in their specific teaching contexts. Anna and Bella in the current study strongly believed that students were capable and that peer review had many benefits. The two teachers put emphasis on the process of peer review, seeking the pathway to high-quality peer feedback that could lead to better revised texts. In other words, they shifted the focus from whether peer review was effective to how peer review could be effective in their own classrooms. The present study has contributed to the research base of peer feedback by looking at how peer feedback was perceived by the teachers who actually used it in their natural teaching contexts.

The effective implementation of peer feedback by the two teachers in the present study can be explained as having three aspects: systematic training, sustained support, and sustained supervision. Firstly, systematic training was reflected in that the teachers used task-specific checklists to train their students before each peer feedback activity. The primary advantage of using checklists as the training tools was that the checklists informed their students of what focal issues they should selectively and primarily target in peer review, because checklists could explicitly guide the students on the content of peer review (Zhao, 2014). Students’ understanding of evaluation points through checklists before embarking on a peer feedback activity could help them know how to give appropriate and substantive feedback (Baker, 2016). Another advantage was that the checklists assist peer reviewers with appropriate language they could use, because linguistic strategy was an essential part of an effective peer review training session (Hu, 2005; Hu & Ren, 2012; Sanchez-naranjo, 2019). Secondly, sustained support was reflected in that the two teachers maintained regular communication with their students to hear concerns and difficulties they encountered in the process of peer feedback. The communication for sustained support in the present study was either in the form of in-class oral group presentations or in the form of written self-reflective reports. As soon as Anna found out reviewer-reviewer or reviewer-writer conflicts in group presentations, she would provide timely interventions and solutions. Lee (2017) advocates that teachers “let students share their experience and concerns”, and “provide opportunities for students to incorporate self-feedback/assessment”. These were two teacher-supported strategies that the teachers in the present study had well adopted. Thirdly, sustained supervision is reflected in that the two expert teachers’ belief that it was not realistic to expect their students to be committed to peer review, unless sustained follow-up teacher feedback on peer review was provided, be it oral praise for excellent peer performance or written comments asking for additional revisions. Through class discussions, Anna was able to evaluate the peer feedback performance and monitor the uptake of peer/teacher comments. It is recommended in the literature that in order to actualize the optimal benefits of peer review, a very important consideration is that students get feedback on how successful they have been in giving feedback – they need evaluative feedback on their actions (Hu, 2005; Zhao, 2014). The advantage of their sustained supervision of peer feedback was that by including accountability and evaluation mechanisms, students could take the activity seriously (Ferris, 2014).

Though it was not within the scope of the present study to investigate whether revisions undertaken as a result of the peer review had enhanced the quality of writing, both teachers and their students had acknowledged its several benefits. The benefits were also evident from the student texts. Peer comments on their students’ texts were specific and constructive. Overall, final drafts were of better quality. For one classification essay-writing task, there were almost no content and organization issues in the fifth (and also final) draft for Anna to comment on, since peer reviewers and the writer had effectively addressed those global issues in the previous drafts. The findings of the present study are in line with previous studies that teachers’ supportive intervention strategies involving discussion and interaction with their peers had a positive impact on students’ attitude on peer review and in turn their writing performance (Hu, 2005; Sanchez-naranjo, 2019).

Another remarkable finding was the two expert teachers’ experimentation, observation, modification and reflection on what worked best in their specific contexts of work. For example, Anna modified rating scales in checklists to open-ended questions and required her students to give formative textual comments in peer review. This finding lends support to Hu’s (2005) conclusion that, in order to actualize the optimal benefits of peer review, teachers should not just understand effective training for successful peer review from published research (i.e., to think globally) but also reflect on their own less successful activities and work out effective ones in their specific teaching context (i.e., to take adequate local action). Through monitoring systematically the success of new activities/actions, the two teachers developed their practical experiential knowledge about a set of strategies that worked effectively in their own teaching context. The finding also confirms that one of the distinctive qualities of expert teachers is their capability of theorizing practical knowledge (Tsui, 2009).

Finally, the present study found that the alignment between class instruction and teacher feedback helped teachers to integrate feedback into part of the teaching class and helped students understand the rationales for teacher and peer feedback. Some writing teachers are worried that if they do not give comprehensive feedback to students, their students will consider them irresponsible teachers (Lee, 2011). Students may hold unrealistic beliefs about a teacher’s responsibility and other aspects of teacher feedback, usually based on their previous experiences, experiences that may not necessarily be beneficial for the development of writing. There is much teachers can do to alter student expectations of and views of teacher feedback. One way is to engage students in the discussion of feedback criteria for different writing tasks and explain them clearly to the students. Anna and Bella provided specific checklists for their students to refer to when they wrote essays and when they did peer reviews. What the two expert teachers did is that they explained to their students explicitly what their feedback criteria were. Otherwise, their students may not have been able to interpret their feedback or act on it as they had intended.

5 Conclusion

The findings of this study on the two expert teachers have pedagogical relevance for front-line writing teachers. Against the assumption that peer review in groups on multiple drafts is not feasible (see Yu et al., 2016, for the cultural issues and other constraints), the study found that students were actually very capable of doing peer review. Teachers should be prepared to understand that peer review is not easy in the beginning. Their students may not feel like doing peer review and may start off simply correcting a few errors, or even make wrong corrections and inappropriate comments. These two expert teachers also shared that these problems were normal when they started to trial peer review. They, however, came to learn from their own experiences that successful peer feedback relied on equipping students with peer review strategies and providing them with systematic sustained supervision and support.

Unlike experimental studies of feedback on limited types of errors conducted in controlled environments that “lack ecological validity” (Storch, 2010: 43), this study reflected real classroom conditions where the teachers provided feedback on valid and authentic writing tasks over a 17-week semester. Acknowledgment should be made here about the practical constraints on the implementation of the recommended practices that include class sizes, exam pressures, shortage of time, etc. The two expert teachers in the case study university also faced these constraints. Thus, by sharing their practices, this study hopes to offer something of interest and use to writing teachers whose teaching contexts resemble those of this study.

References

Badger, R., & White, G. (2000). A process genre approach to teaching writing. ELT Journal, 54, 153–160.

Baker, K. M. (2016). Peer review as a strategy for improving students’ writing process. Active Learning in Higher Education, 17, 179–192.

Barnard, R., & Burns, A. (Eds.). (2012). Researching language teacher cognition and practice: International case studies (p. 2012). Multilingual Matters.

Basturkmen, H. (2012). Review of research into the correspondence between language teachers’ stated beliefs and practices. System, 40, 282–295.

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition and language education: Research and practice. Continuum.

Breen, M. P., Hird, B., Milton, M., Oliver, R., & Thwaite, A. (2001). Making sense of language teaching: Teachers’ principles and classroom practices. Applied Linguistics, 22, 470–501.

Chang, C. Y.-H. (2016). Two decades of research in L2 peer review. Journal of Writing Research, 8, 81–117.

Du, H. (2012). College English teaching in China: Responses to the new teaching goal. TESOL in Context, 3, 1–13. Retrieved from http://www.tesol.org.au/files/files/278_hui_du.pdf

Ferris, D. R. (2003). Response to student writing: Implications for second language students. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ferris, D. R. (2014). Responding to student writing: Teachers’ philosophies and practices. Assessing Writing, 19, 6–23.

Ferris, D. R., Brown, J., Liu, H. S., & Stine, M. E. A. (2011). Responding to L2 students in college writing classes: Teacher perspectives. TESOL Quarterly, 45, 207–234.

Freeman, D. (2002). The hidden side of the work: Teacher knowledge and learning. Language Teaching, 35, 1–13.

Freeman, D., & Richards, J. C. (1996). Teacher learning in language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Goldstein, L. M. (2001). For Kyla: What does the research say about responding to ESL writers. In T. Silva & P. K. Matsuda (Eds.), On second language writing (pp. 73–90). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Goldstein, L. M. (2005). Teacher written commentary in second language writing classrooms. University of Michigan Press.

Hu, G. W. (2002). Potential cultural resistance to pedagogical imports: The case of communicative language teaching in China. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 15, 93–105.

Hu, G. W. (2005). Using peer review with Chinese ESL student writers. Language Teaching Research, 9, 321–342.

Hu, G. W., & Lam, S. (2010). Issues of cultural appropriateness and pedagogical efficacy: Exploring peer review in a second language writing class. Instructional Science, 38, 371–394.

Hu, G. W., & Ren, H. W. (2012). The impact of experience and beliefs on Chinese EFL student writers feedback preferences. In R. Tang (Ed.), Academic writing in a second or foreign language: Issues and challenges facing ESL/EFL academic writers in higher education contexts (pp. 67–87). Continuum.

Huisman, B., Saab, N., Den Broek, P. V., & Van Driel, J. H. (2018). The impact of formative peer feedback on higher education students’ academic writing: A meta-analysis. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44, 863–880.

Hyland, K., & Hyland, F. (2006). Feedback on second language students’ writing. Language Teaching, 39, 83–101.

Jin, L., & Cortazzi, M. (2006). Changing practices in Chinese cultures of learning. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 19, 5–20.

Lee, I. (2008). Understanding teachers’ written feedback practices in Hong Kong secondary classrooms. Journal of Second Language Writing, 17, 69–85.

Lee, I. (2011). Working smarter, not working harder: Revisiting teacher feedback in the L2 writing classroom. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 67, 377–399.

Lee, I. (2017). Classroom assessment and feedback in L2 school contexts. Springer.

Mei, T., & Yuan, Q. (2010). A case study of peer feedback in a Chinese EFL writing classroom. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 33(4), 87–98.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (3rd ed.). Sage.

Montgomery, J. L., & Baker, W. (2007). Teacher-written feedback: Student perceptions, teacher self-assessment, and actual teacher performance. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16, 82–99.

Pan, L., & Block, D. (2011). English as a “global language” in China: An investigation into learners’ and teachers’ language beliefs. System, 39, 391–402.

Richards, J. C. (2010). Competence and performance in language teaching. RELC Journal, 41, 101–122.

Saldana, J. (2000). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE.

Sanchez-naranjo, J. (2019). Peer review and training: Pathways to quality and value in second language writing. Foreign Language Annals, 52(3), 612–643.

Storch, N. (2010). Critical feedback on written corrective feedback research. International Journal of English Studies, 10(2), 29–46.

Tsui, A. (2009). Distinctive qualities of expert teachers. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15, 421–439.

Tsui, A., & Ng, M. (2000). Do secondary L2 writers benefit from peer comments? Journal of Second Language Writing, 9, 147–170.

Wang, P. (2010). Dealing with English majors’ written errors in Chinese universities. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 1(3), 194–205.

Wei, Y., & Chen, Y. (2003). Supporting Chinese learners of English to implement self assessment in L2 writing. Proceedings of the Independent Learning Conference 2003. Retrieved from http://www.independentlearning.org/uploads/100836/ila03_wei_and_chen.pdf

Yang, L. X. (2010). Gaoxiao yingyu zhuanye jiaoshi xuezuo jiaoxue xinnian yu jiaoxue shijian: Jingyan jiaoshi ge’an yanjiu [University English writing teachers’ beliefs and practices: A case study of experienced teachers]. Waiyu Jiaoxue Lilun yu Shijian [Foreign Language Learning Theory and Practice], 2, 59–68.

Yang, M., Badger, R., & Yu, Z. (2006). A comparative study of peer and teacher feedback in a Chinese EFL writing class. Journal of Second Language Writing, 15, 179–200.

You, X. (2004a). “The choice made from no choice”: English writing instruction in a Chinese University. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13, 97–110.

You, X. (2004b). New directions in EFL writing: A report from China. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13, 253–256.

Yu, S., Lee, I., & Mak, P. (2016). Revisiting Chinese cultural issues in peer feedback in EFL writing: Insights from a multiple case study. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25, 295–304.

Zhang, D. (2005). Teaching writing in English as a foreign language: Mainland China. In M. S. K. Shum & D. L. Zhang (Eds.), Teaching writing in Chinese speaking areas (pp. 29–45). Springer.

Zhang, P. (2008). Yingyu jiaoshi xiezuo jiaoxue xinnian yu jiaoxue shijian de shizheng yanjiu [An empirical study on English teachers’ beliefs about and practices in writing instruction]. Yuwen Xuekan [Journal of Language and Literacy Studies], 11, 157–160.

Zhang, X., & Mceneaney, J. E. (2019). What is the influence of peer feedback and author response on Chinese university students’ English writing performance? Reading Research Quarterly, 55(1), 123–146.

Zhao, H. (2014). Investigating teacher-supported peer assessment for EFL writing. ELT Journal, 68, 155–168.

Acknowledgements

I thank my supervisor Professor Hu Guangwei. I also thank Nanyang Technological University for awarding me a graduate research scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Yang, J. (2022). Factors Impacting Upon Writing Teachers’ Feedback Choices. In: Hamp-Lyons, L., Jin, Y. (eds) Assessing the English Language Writing of Chinese Learners of English. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92762-2_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92762-2_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-92761-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-92762-2

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)