Abstract

Two interactive, non-linear, fictional, movie theater projects are described. The first, Ressaca, was released in 2008. A live-editing interface sits between the audience and the main screen. It is usually manipulated by the director, who creates a new improvised ordering of the sequences in each screening. The second one, Dispersão, was not yet launched. The interaction device is provided by the mobile phones of the audience: viewers may use an app which simulates a social network used by the movie characters. The engagement of the audience will interfere with the unfolding of the story. Agencies, syuzhets and algorithms for both experiences are discussed. Finally the article locates these projects as belonging to the field of interactive digital narratives specific to the movie theater, and also part of poorly charted tradition of interactive media from developing countries.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

This demo paper describes two interactive cinema experiences created by the author, namely Ressaca (Hangover) and Dispersão (Dispersion). Both are meant for movie theaters, have feature film length (between 75 and 120 min) and portray fictional stories based in local historical events. They also share a collective device of agency and a non-branching narrative based on audiovisual lexia [8] which are the movie sequences. We will describe narrative, interactive and technical aspects and situate them in the context of interactive visual storytelling.

2 Ressaca

The movie follows the puberty and teenage years of a middle-class Brazilian during the turbulent times of re-democratization in the 80’s and 90’s. During that period, the country faced economic crisis, hyperinflation, dead and impeached presidents.

The project’s interaction device is a 1-m round touch screen that stands between the main screen and the audience. The device (Fig. 1), baptized as Engrenagem (Sprocket) was developed and programmed by Maíra Sala [2], and is inspired by the musical interface named Reactable [5]. It is manipulated any one person with sufficient knowledge of the material and interface. It works effectively as an editing tool, allowing the user to create an order for the pre-edited sequences and even the individual shots of the film in real time. The usual session starts with 5–10 sequences overhead, and subsequent lexia were added impromptu, according to the will of the editor, which could be influenced by the reaction of the audience, his or her mood, or a specific goal like focusing on one of the stories. The movie has 128 sequences in total [6], and a session could use anything between fifty to eighty from them.

Ressaca was released in 2008 and exhibited in several festivals and venues throughout the world until 2011. It won four awards, including Best Film in Cinesquemanovo 2009 [7], in Porto Alegre, Brazil. This was the only festival in which it took part of the competition. In others, the project was shown in non-competitive screenings.

The goal of the project was to offer a non-linear experience that didn’t disrupt the immersive cinema experience by asking the audience to make choices. The “editor” – the director himself, most of the times – assumes a role of representing the audience [9]. At the same time, the imposing presence of the interface and the movements of the person manipulating it introduce an element of risk. There is tension in building the storyline. Any mistakes in the operation can be noticed by the public. In other words, Ressaca brings elements of live performances, which are the rule in theater representations, to the cinematic experience.

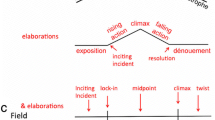

The storytelling device does not offer a branching, tree-like structure: topology-wise it could be considered arbitrary [10], although the term doesn’t take into account the fact that the decisions made by the editor are not arbitrary, but based on several factors. There is not a predefined path, and any random trajectory might result in interesting concatenations. The structure is inspired by the strategy used by novelist Cortázar in Hopscotch: some syuzhets [1] are suggested, but the reader is also welcome to explore the chapters freely and created his or her own experience. There are paths to follow, and some of the lexia are better connected to a small set of others. It is a navigation that yields better results when the agent has familiarity with these features. I call this particular strategy a narrative landscape: previous knowledge of the ground leads to satisfying routes, but random walkabouts will also take the viewer to unexpected corners with surprising shortcuts. The naming also serves as a nod to Jeffrey Shaw pioneering cinema work.

3 Dispersão

In 2018, we started a new project continuing our research on cinema and non-linear narratives. Dispersão (Dispersion) [3] is also a feature-length experience created for movie theaters, and offers a collective narrative agency. But instead of relying on a representative to decide on the storytelling route, this project puts the structuring of the sequences on the hands of viewers.

The audience of the film receives information on the story and characters through two different streams: the first and more visible is the big theater screen, where live action scenes take place. And the other is the mobile phone of each viewer. A social network app was created specially for the project, again by creative developer Maíra Sala. This software imitates the mechanism of a micro-blogging platform, except that its participants are not the moviegoers, but the characters of the movie. Thus, events on the main story told on the theater screen might trigger some posts and comments inside the app.

Even though the spectators cannot make posts, they can interact with the app by reacting to them. And that is exactly the interactive strategy for storytelling: the system will choose the next sequences depending on the engagement with each post. The rationale here follows the logic of existing commercial social networks. If a posts provokes more engagement it means that the audience is interested in the character, and/or the plot around it. In the case of a platform like Twitter, this would make the post be shown to a greater number of users (as it proves to be more popular) and would also bring up more posts related to it to the particular user who “liked” it. And in the case of the collective audience of Dispersão in the movie theater, this would have the effect of guiding the stories towards that plot and/or character, by selecting specific sequences.

The algorithm behind it includes a classification of each sequence according to the plot, character and “ideal” position in the movie. This position is related to the narrative structure, but it is not necessarily dictated by a chronological order: some sequences might work well both in the beginning and the end of the movie, for instance. A modified logistic function is used, taking as parameter the distance to the ideal position. The result is used as a weight in random selection of the next scene.

The story also evolves around the effects of politics in the lives of characters, and is set around 2011–2016, during the crisis of the left wing government in Brazil. The project was delayed by the COVID pandemic and is now expected to be released in the beginning of 2022. Even though the software development and post-production phases are finished, live tests could not yet be made.

The topology of the lexia in Dispersão was created after the experiences in Ressaca. It is a mix of hardwiring some connections and leaving enough room for chance and audience control through the algorithm described above. Again, it is difficult to classify the narrative algorithm based on the topology. The proposed category of narrative landscape still applies to the method, as it has simply been partially fixed into software. The devices used – mobile phones – are nonetheless intrusive and might create disruptions. Their use during sessions, no matter how much a widespread habit it is, is still frowned upon. It remains to be seen how much of a liability or a benefit this will be for the cinematic experience.

4 Conclusion

When discussing the future of the Interactive Digital Narratives field, Murray proposes this image of a kaleidoscope of multiple taxonomies and artifacts [4]. The projects described here are to be found in a very specific branch of this looking glass, the one dedicated to collective interactive experiences that take place inside the movie theater. But even within this small field, they belong to a more exotic leaf which aggregates the ones produced in the periphery of the western world - in developing countries.

It is hard to claim novelty on such projects when there isn’t even a reference frame to discuss them in the same language. A quick lookup on an academic search engine reveals three pages of articles dedicated to the project Ressaca written in Portuguese or Spanish, and not one single document in English, even after more than a decade from its inception.

Practitioners from the global south are used to being subject to “discoveries”, specially if their practice is performed in non hegemonic languages. This demo proposes to fill a gap in the documentation of such practice. By opening a small crack in this wall, I hope that new projects - like “Dispersão” - can find a voice of their own, free from a colonialist perspective.

References

Bordwell, D.: Narration in the Fiction Film. Routledge, Abingdon (2013)

Coutinho, E.L., Pinto, I.: A participação do espectador no filme Ressaca (2011)

Dispersão website. https://web.archive.org/web/20190710073406/, http://dispersao.net/. Accessed 11 Oct 2021

Murray, J.H.: Research into interactive digital narrative: a kaleidoscopic view. In: Rouse, R., Koenitz, H., Haahr, M. (eds.) ICIDS 2018. LNCS, vol. 11318, pp. 3–17. Springer, Cham (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04028-4_1

Reactable. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reactable. Accessed 11 Oct 2021

Ressaca edited scenes. https://archive.org/details/ressaca. Accessed 11 Oct 2021

Ressaca wins Cinemaesquemanovo Festival. https://web.archive.org/web/20091029191702/https://g1.globo.com/Noticias/Cinema/0,,MUL1354133-7086,00.html. Accessed 11 Oct 2021

Ross, C.: Hypertext 2.0: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory (1999)

Rodrigues, A.C.: Live Cinema: Autoria Coletiva em Narrativas Objetivas e Subjetivas (2015)

van Dyke Parunak, H.: Hypermedia topologies and user navigation. In: Proceedings of the Second Annual ACM Conference on Hypertext, pp. 43–50 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1145/74224.74228

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Vianna, B.C. (2021). Ressaca and Dispersão: Experiments in Non-linear Cinema. In: Mitchell, A., Vosmeer, M. (eds) Interactive Storytelling. ICIDS 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 13138. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92300-6_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-92300-6_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-92299-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-92300-6

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)