Abstract

The Italian scientists have a long tradition of studies and research on the many large pelagic species, including also the tropical tuna species. Even if tropical tunas are important for the Italian industry since more than a century, they were only occasionally studied by Italian researchers. This paper attempts to list together the papers published so far by Italian scientists, concerning the biology of these species, the fisheries and many other scientific and cultural issues. The aim of this paper is to provide an annotated bibliography, with specific keywords in English, even if the bibliography is surely incomplete, because some papers are very difficult to be find. This annotated bibliography, which includes 88 papers, was set together to serve the scientists and help them in finding even some rare references that might be useful for their work.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Acanthocybium solandri

- Annotated bibliography

- Atlantic Ocean

- Bigeye tuna

- Biology

- Black skipjack

- Blackfin tuna

- Canning industry

- Catches

- Cero

- Contaminants

- Eastern Pacific bonito

- Economy

- Euthynnus affinis

- Euthynnus lineatus

- Feeding

- Fishery

- Food safety

- Genetics

- History

- Indian mackerel

- Indian Ocean

- Kawakawa

- King mackerel

- Katsuwonus pelamis

- Longlines

- Longtail tuna

- Mediterranean Sea

- Migrations

- Nomenclature

- Narrow-barred Spanish mackerel

- Pacific Ocean

- Purse-seines

- Reproduction

- Rastelliger kanagurta

- Sarda chiliensis

- Scomberomorus brasiliensis

- Scomberomorus cavalla

- Scomberomorus commerson

- Scomberomorus regalis

- Scomberomorus tritor

- Serra Spanish mackerel

- Skipjack tuna

- Southern bluefin tuna

- Systematics

- Techniques

- Technology

- Thunnus albacares

- Thunnus atlanticus

- Thunnus maccoyii

- Thunnus obesus

- Thunnus tonggol

- Tropical tunas

- Tuna industry

- Wahoo

- West African Spanish mackerel

- Yellowfin tuna

1 Foreword

Several species belonging to the tropical tunas have been traded since the early beginning of the twentieth century by the Italian canning industries, mostly for increasing the tuna availability on the domestic market. They also raised the curiosity of some Italian scientists when they had the opportunity to carry out research campaigns in tropical waters, particularly at the time when Italy had some colonies or, in more recent times, during international cooperative activities.

This paper would like to provide the annotated overview of the Italian literature on several species of tropical tunas: skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis (Linnaeus, 1758) (FAO code: SKJ), narrow-barred Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus commerson (Lacépède, 1800) (FAO code: COM), West African Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus tritor (Cuvier, 1832) (FAO code: MAW), serra Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus brasiliensis Colette, Russo and Zavala-Camin, 1978 (FAO code: BRS), cero, Scomberomorus regalis (Block, 1793) (FAO code: CER), king mackerel, Scomberomorus cavalla (Cuvier, 1829) (FAO code: SSM), wahoo, Acanthocybium solandri (Cuvier, 1832) (FAO code: WAH), Indian mackerel, Rastrelliger kanagurta (Cuvier, 1816) (FAO code: RAG), black skipjack, Euthynnus lineatus (Kishinouye, 1912) (BKJ), kawakawa, Euthynnus affinis (Cantor, 1849) (FAO code: KAW, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares (Bonnaterre, 1788) (FAO code: YFT), bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus (Lowe, 1839) (FAO code: BET), blackfin tuna, Thunnus atlanticus (Lesson, 1831) (FAO code: BLF), southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii (Castelnau, 1872) (FAO code: SBF), longtail tuna, Thunnus tonggol (Bleeker, 1851) (FAO code: LOT), and eastern Pacific bonito, Sarda chiliensis (Cuvier, 1832) (FAO code: BEP). Usually, some RFMOsFootnote 1 group the tropical tuna species under the general code TRO.

Some papers were written in Italian, a language which is now not on the list of the three official languages (French, English and Spanish) used in ICCATFootnote 2 and in other tuna RFMOs, and therefore, possibly some foreign scientists have problems in understanding the contents.

Another reason for setting-up this Italian annotated bibliography is because some papers are not available in electronic format, and therefore, some young researchers, who are no longer used to studying and mining in traditional libraries, could be likely unable to detect the various studies that have been carried out so far on these species.

Therefore, it is a sort of national proudness trying to set-up the list of papers on these species that it was possible to find so far, annotating them with keywords in English for improving the opportunities to detect them with an electronic searching engine.

A very first and limited Italian annotated bibliography on tropical tunas was tentatively provided by Di Natale (2020), even if some annotated papers were already included in the fundamental work on tuna species provided by Corwin (1930) and later updated by Van Campen and Hoven (1956). An indexed bibliography including tropical tunas, limited to tagging, was published by Bayliff (1993). Not-annotated literature reviews including also tropical tuna species were provided by Collette and Nauen (1983), Pillai and Mallia (2007) and Collette and Graves (2019).

2 Criteria

The bibliography on tropical tunas (skipjack tuna, narrow-barred Spanish mackerel, West African Spanish mackerel, serra Spanish mackerel, cero, king mackerel, wahoo, Indian mackerel, kawakawa, black skipjack, yellowfin tuna, bigeye tuna, blackfin tuna, southern bluefin tuna, longtail tuna and eastern Pacific bonito) included in this work was selected when an Italian scientist was the only author of a paper or when one or more Italian scientists were among the authors of collective papers.

This was the primary criterion used for selecting the many titles, independently if they were peer-reviewed papers, books, not-peer-reviewed papers, papers presented in conferences or meetings or congresses, reports to public administrations or project reports. A secondary criterium for paper selection considered those documents directly related to the target species, even if, in some cases, the tropical tunas are concerned by just a part of the text.

When vernacular names or old scientific names were used in the original paper, they were possibly listed in the annotation. The annotations required each paper to be checked in detail and this implied a huge workload.

The annotations show the main subjects in the content, and the descriptors proposed by ASFIS (Fagetti et al., 2009) have been mostly used, adding additional descriptors when necessary. As concerns the main species included in each reference, we used both the international common name(s) and the Latin name(s).

3 Discussion

Even if most of the scientific efforts of the Italian scientists over the years were devoted to the Mediterranean species, some of them worked also on tropical tuna species, thanks to the interest of the tuna industry to use these tunas. Very few research campaigns were targeting tropical tunas in the past, even if some Italian vessels were fishing also in tropical areas. The interest, in recent years, has been mostly for management or conservation studies, food safety issues and for genetic research.

The titles which are now available surely constitutes a very useful reference list for all the researchers working on tropical tunas (skipjack tuna, narrow-barred Spanish mackerel, West African Spanish mackerel, serra Spanish mackerel, cero, king mackerel, wahoo, Indian mackerel, black skipjack, yellowfin tuna, bigeye tuna, blackfin tuna, southern bluefin tuna, longtail tuna and eastern Pacific bonito) and it also includes some rare papers. The opportunities provided by the web are improving the number of available articles on these species and their fisheries.

In most of the cases, when checking a document, it was possible to discover additional literature which was previously not available, transforming a part of this work as a continuous journey following Ariadne’s thread.

At the same time, during this bibliographic research, it was amazing to learn so many additional details about these species. Going through the various titles (and the text behind) in the bibliography, it is possible to find important information on many aspects of their life history and fisheries.

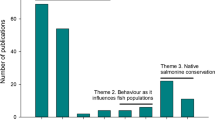

This work provides a list of 88 papers, all published between 1884 and 2020 (Fig. 1). Very generic references to tropical tuna species sometimes exist or can be suspected in older papers, even in the sixteenth century, but they are too imprecise and generic, and therefore, these works were not listed in this bibliography. The very first specific reference is by Premi (1884), followed by Pavesi (1887). No papers on tropical tunas were published in the first two decades of the twentieth century, 1 paper was published in the ‘20s, 4 papers were published in the ‘30s, when several fish were imported to Italy from the Italian colonies or from the Atlantic Ocean and when there was a specific interest from the tuna industry. Again, there was another decade without any paper in the ‘40s, due to the 2nd World War. The Italian scientific production on tropical tunas very slowly resumed after the ‘40s, smoothly growing till the ‘90s, when 9 papers were published. Then, due to the growing scientific and commercial interest, 18 papers (20.45%) were published between 2000 and 2009, peaking at 39 papers (43.32%) in the last decade, mostly due to conservation issues. Additional 8 papers were published in 2020.

Most of the references (61 papers, 69.32%) are in English, mirroring the fact that the majority of the papers were published in very recent years. 25 papers (28.41%) are in Italian because these papers were published when the Italian language was mandatory, or when foreign languages were not used, or because they were Italian official domestic reports, and likely this fact makes them less usable. The remaining 2.27% of the papers are written in Spanish or in Italian/English (1 paper each). Figure 2 provides a graphic image of the languages used by the Italian authors in papers on tropical tunas which are listed in this annotated bibliography.

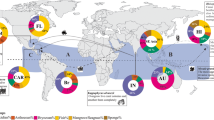

The annotations allow identifying most of the many themes included in each paper. Tables 1a and 1b shows the most relevant themes in the annotations and it is interesting to see how many aspects of the tropical tunas have been examined by the various Italian authors. Most of the papers are specifically related to the Atlantic Ocean (57 papers, 64.77%), but the studies include also the Pacific Ocean (47 papers, 53.41%), the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea (42 papers each, 47.73% each) and the Red Sea (3 papers, 3.41%).

The various countries concerned are also identified, with a majority of papers concerning Italy (23 papers, 26.14%), 6 papers related to Spain (6.82%), and then Croatia, France, Japan and Malta, with 5 papers each (5.68% each); other 21 countries are less mentioned. Among these species, the yellowfin tuna is included in 41 papers (46.59%), the skipjack tuna is mentioned in 26 papers (29.55%), the bigeye tuna and the albacore tuna are mentioned in 22 papers each (25% each), the southern bluefin tuna is mentioned in 15 papers (17.05%), the Pacific bluefin tuna is mentioned in 10 papers (11.36%), while the other species are less mentioned.

The fishing methods also have a clear relevance: the longline fishery is mentioned in 20 papers (22.73%), the purse-seine fishery is mentioned in 14 papers (15.91%), the traps are mentioned in 10 papers (11.36%) and the line fisheries (hand lines and troll lines) are mentioned in 9 papers (10.23%), while the other fisheries are less represented. Conflicts with other activities are mentioned in just 1 paper (1.14%), while the various impacts caused by the gears are mentioned in 6 papers (6.82%); by-catch is reported in 7 papers (7.95%).

The biology is included in 12 papers (13.64%), but the generic analyses (16 papers, 18.18%) and genetic studies (14 papers, 15.91%) are more relevant; food safety or security is the subject of 10 papers (11.36%), heavy metals and mercury are mentioned in 9 papers each (10.23% each) and bioaccumulation or contaminants are mentioned in 7 papers (7.95%); all these issues are very important for the tuna canning industry.

The management is included in 10 papers (11.36%), generic RFMOs are mentioned in 6 papers (6.82%), stock structure is mentioned in 4 papers (4.55%), while the conservation status concerns 15 papers (17.05%) and IUCN is mentioned in 16 papers (18.18%).

The tuna trade and the tuna industry are reported in 19 papers each (21.59% each), the markets are reported in 18 papers (20.45%), the canning industry is reported in 15 papers (17.05%), while several aspects of the tuna economy are also mentioned in various papers. The social problems are mentioned in 4 papers (4.55%), while social sciences, traditions, history, fishermen, food habits, culture and many other themes are also included in other papers.

Table 2 shows the ranking of the main authors included in the Italian annotated bibliography on tropical tunas, over a total of 146 authors. Based on the institutional workplace of each author, it is very clear that the most of the authors are belonging to the four main research centres targeting the large pelagics in Italy: Messina, Bologna-Fano, Genova and Bari, where Universities and other research institutes were historically located. Among the authors, there are most of the Italian national research coordinators for the large pelagics over the years (Arena, De Metrio, Piccinetti and Di Natale). Just one paper is by an anonymous author(s).

Due to the number of references, the Italian annotated bibliography on tropical tunas is provided in Annex 1 to this paper.

4 Conclusion

This work was able to find also the several scientific expeditions carried out by Italian scientists on tropical oceans, such as those by Bini in the Atlantic Ocean (1931 and 1936) and in the Pacific Ocean (1952), by Ninni in the Red Sea (1931) and by Arena in West African waters (1964 and 1967), papers that are usually never mentioned by foreign scientists working on tropical tunas. Therefore, listing them in this annotated bibliography is someway important.

Even if it is evident that the tropical tunas have been not the main scientific interest of Italian scientists, it is clear that several research activities have been conducted on many species, mostly in the last century. The list of scientific papers on tropical tunas here provided is still certainly incomplete but the aim of this work is also to further stimulate scientists to provide additional titles, with the purpose to create a very complete reference list to be used by all the researchers working on these species or on related subjects, for helping them in their work.

It is sure that additional documents are certainly existing, but it was not possible to find them during this bibliographic research. Indeed, this is a never-ending work and possibly this work will be never completed.

In recent years many scientists and particularly (but not only) young researchers are adopting a sort of selective attitude when they prepare their papers, avoiding even to mention papers that were not published in peer-review journals or by scientists who are competing with them. This attitude is clearly causing a serious scientific problem because there are several very recent papers that are not at all using the knowledge available so far, which sometimes means forgetting an important part of the scientific knowledge and culture we already have.

Clearly, this paper can improve the knowledge on available Italian studies on tropical tunas and this annotated bibliography was made exactly for providing a helping hand to all the colleagues working on these species.

Notes

- 1.

RFMOs: Regional Fishery Management Organisations.

- 2.

ICCAT: International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas.

References

Arena, P. 1964. Missione di studio sulla pesca in Africa Occidentale. Rapporto al Centro Sperimentale della Pesca, Messina: 1–85.

Arena, P. 1967. La pesca del tonno nell’Atlantico intertropicale. Rivista Della Pesca, Luglio-Settembre 3: 536–590.

Bayliff, W.H. 1993. An indexed bibliography of papers on tagging of tunas and billfishes. Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, La Jolla (CA, USA). Special Report, 8: 1–91.

Bini, G. 1931. Rapporto sulla crociera di pesca del tonno compiuta a bordo del piropeschereccio “Orata” nell’Atlantico. Boll. Pesca, Piscic. Idrobiol., 7(I): 57–90.

Bini, G. 1936. La pesca oceanica e l’industria del pesce congelato. Boll. Pesca, Piscic. Idrobiol., 12(IV): 1–16.

Bini, G. 1952. Osservazioni sulla fauna marina delle coste del Chile e del Perù con speciale riguardo alle specie ittiche in generale ed ai tonni in particolare. Boll. Pesca, Piscic. Idrobiol., 28(VII n.s.), 1: 11–60.

Collette, B.B., C.E. Nauen. 1983. FAO species catalogue. Vol. 2. Scombrids of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of tunas, mackerels, bonitos and related species known to date. FAO Fish. Synop., 125 (2): 1–137.

Collette, B., J. Graves. 2019. Tunas and Billfishes of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore (USA): 1–351.

Corwin, G. 1930. A bibliography of the Tunas. Div. Fish and Game California, Fishery Bulletin n. 22: 1–103.

Di Natale, A. 2020. The Italian annotated bibliography on tropical tunas. SCRS/2020/113, Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 77 (8): 1–17.

Fagetti E., D.W. Privett, J.R.L. Sear. 2009. Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Thesaurus. Descriptors Used in the Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Information System. Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Information System. ASFIS reference Series, 6 (rev. 3), FAO, Rome: 1–312.

Ninni, E. 1931. Relazione sulla campagna esplorativa di pesca nel Mar Rosso, Febbraio-Marzo 1929. Boll. Pesca, Piscic., Idrobiol. Roma, VII, 2: 1–77.

Pavesi, P. 1887. Le migrazioni del Tonno. Rendiconti Dell’Istituto Lombardo Di Scienze e Lettere, Milano, 2 (20): 311–324.

Pillai, N.G.K., J.V. Mallia. 2007. Bibliography on Tunas. Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi (India). Spl. Publ., 92: 1–325.

Premi, C.B. 1884. Consumo del pesce salato in Italia. Il progetto d’aumento del dazio sul tonno estero. Tip. Ciminago, Genova: 1–64.

Van Campen W.G., Hoven E.E., 1956. Tunas and tuna fisheries of the World. An annotated bibliography, 1950–1953. US Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Services, Washington, Fishery Bulletin, 111 (57): 178–249.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Annex 1: Annotated Italian Bibliography on Tropical Tunas (TRO)

Annex 1: Annotated Italian Bibliography on Tropical Tunas (TRO)

-

1.

Anonymous, 1927. La produzione di pesci in iscatola negli Stati Uniti durante l’anno 1926. Boll. Pesca Piscic. Idrobiol., 3 (5): 17–18.

-

i.

Tuna industry, canned tuna, production, export, tropical tunas, Thunnus spp., United States, Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

2.

Arena P., 1964. Missione di studio sulla pesca in Africa Occidentale. Rapporto al Centro Sperimentale della Pesca, Messina: 1–85.

-

i.

Experimental fishery, exploratory fishery, fishery research, bottom trawl fishery, coastal fishery, pelagic fishery, longline fishery, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, Atlantic little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, albacora, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye, Thunnus obesus, Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal, Nigeria, West Africa, Gulf of Guinea, western Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

3.

Arena P., 1967. La pesca del tonno nell’Atlantico intertropicale. Rivista della Pesca, Luglio-Settembre, 3: 536–590.

-

i.

Longline fishery, purse-seine fishery, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, albacora, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye, Thunnus obesus, Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal, Nigeria, West Africa, Gulf of Guinea, Tropical seas, western Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

4.

Baiocchi C., Medana C., Dal Bello F., Giancotti R., Aigotti R., Gastaldi D., 2015. Analysis of regioisomers of polyunsaturated triacylglycerols in marine matrices by HPLC/HRMS. Food Chemistry, 166: 551–560. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308814614009534 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.06.067.

-

i.

Fish oil, tuna oil, algae oil, analyses, mass spectrometry, thermal induced fragmentation, CID MS/MS tag fragmentation, HPLC/HRMS methodology, Omega-3 fatty acids, intestine absorption, polyunsaturated triacylglycerols composition, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares.

-

i.

-

5.

Barbujani F., 1980. I problemi della conservazione e trasformazione dei prodotti ittici. In: Contributo della Pesca alla soluzione del problema alimentare. Atti Conf. Naz. Pesca, CNEL, Roma: 169–190.

-

i.

Industry, preserves, canning, import, export, market, distribution, marketing, fish consumption, nutritional value, energy inputs, food safety, frozen products, refrigerated products, vacuum products, dried products, cod, Gadus morhua, tropical tunas, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, Italy, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

6.

Bayona-Vásquez N.J., Glenn T.C., Uribe-Alcocer M., Pecoraro C., Díaz-Jaimes P., 2018. Complete mitochondrial genome of the yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) and the blackfin tuna (Thunnus atlanticus): notes on mtDNA introgression and paraphyly on tunas. Conservation Genetics Resources, 10 (4): 697–699.

-

i.

Genetic analyses, mitochondrial genome, DNA, nuclear loci, paraphyly, phylogenetic relationship, introgression, genus Thunnus, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, blackfin tuna, Thunnus atlanticus, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

7.

Bernardi C., Tirloni E., Cattaneo P., 2015. Content of methylmercury in swordfish (Xiphias gladius), tuna (Thunnus thynnus and Thunnus albacares) and sharks (Prionace glauca, Mustelus mustelus and Isurus oxyrinchus): Estimation of the exposure on the Italian consumer. Industrie Alimentari, 54: 5–12.

-

i.

Heavy metals contamination, bioaccumulation, methylmercury, provisional tolerable weekly intake, PTWI, health problems, consumers, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, blue shark, Prionace glauca, smooth–hound, Mustelus mustelus, shortfin mako, Isurus oxyrinchus, Italy, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

8.

Bernardi C., Tirloni E., Stella S., Anastasio A., Cattaneo P., Colombo F., 2019. ß-hydroxyacyl-CoA-dehydrogenase activity differentiates unfrozen from frozen-thawed Yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares). Italian Journal of Food Safety, 8 (3): 6971. https://doi.org/10.4081/ijfs.2019.6971.

-

i.

Frozen-thawed tuna, HADH, ß-hydroxyacyl-CoA-dehydrogenase activity, fresh-frozen differentiation, formaldehyde, dimethylamine, trimethylamine oxide, import, export, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Italy, Maldives, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

9.

Bini G., 1931. Rapporto sulla crociera di pesca del tonno compiuta a bordo del piropeschereccio “Orata” nell’Atlantico. Boll. Pesca, Piscic. Idrobiol., 7(I): 57–90.

-

i.

Experimental fishery, fishing gear, gear technology, longlines, size measurements, yellowfin tuna, Neothunnus albacora, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna, Parathunnus obesus, Thunnus obesus, Canary Islands, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

10.

Bini G., 1936. La pesca oceanica e l’industria del pesce congelato. Boll. Pesca, Piscic. Idrobiol., 12(IV).

-

i.

Oceanic fishery, trawl fishery, longline fishery, demersal species, fishing industry, frozen fish, yellowfin tuna, Neothunnus albacora, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna, Parathunnus obesus, Thunnus obesus, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

11.

Bini G., 1952. Osservazioni sulla fauna marina delle coste del Chile e del Perù con speciale riguardo alle specie ittiche in generale ed ai tonni in particolare. Boll. Pesca, Piscic. Idrobiol., 28 (VII n.s.), 1: 11–60.

-

i.

Fish distribution, biology, reproduction, populations, migrations, juveniles, oceanography, environmental conditions, description, iconography, bibliography, yellowfin tuna, Neuthunnus macropterus, Thunnus albacares, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, eastern Pacific bonito, Sarda chiliensis, albacore, Thunnus germo, Thunnus alalunga, Chile, Peru, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

12.

Bonanno A., Douglas H. C., 1996. Caught in the Net: The Global Tuna Industry, Environmentalism and the State. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas: 1–346.

-

i.

Global tuna industry, global markets, tuna ranching, dolphin safe label, purse-seine fishery, tuna fisheries, export, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii, bigeye, Thunnus obesus, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

13.

Camiñas A., Di Natale A., Munch-Petersen S., Blasdale T., Casale P., Calvo A., Deflorio M., Giacoma C., Concalves J., Kapantagakis A., Margaritoulis D., Pinnegar J., Althoff W., Astudillo A., Biagi F., Sheperd I., Weissenberger J., 2005. Drifting longline fisheries and their turtle by-catches: biological and ecological issues, overview of the problems and mitigation approaches. Report of the first meeting of the subgroup on by-catches of turtles in the EU longline fisheries (SGRST/SGFEN 05–01) of the Scientific, Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF) of the Commission of the European Communities, Bruxelles, 4–8 July 2005. Commission Staff Working Paper, SEC(2005): 1–87.

-

i.

Pelagic longline fisheries, gear impact, impact evaluation, biology, ethology, behaviour, ecology, target species, by-catch, hooks, gear technology, fleets, CPUE, mitigation measures, marine turtles, IUCN status, loggerhead turtle, Caretta caretta, green turtle, Chelonia mydas, hawksbill turtle, Eretmochelys imbricata, Kemp’s ridley turtle, Lepidochelys kempi, olive ridley turtle, Lepidochelys olivacea, flatback turtle, Natator depressus, leatherback turtle, Dermochelys coriacea, porbeagle, Lamna nasus, blue shark, Prionace glauca, mako shark, Isurus oxyrinchus, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna Thunnus obesus, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, longbill spearfish, Tetrapturus pfluegeri, Atlantic bonito, Sarda sarda, Angola, Cape Verde, Cyprus, France, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Gambia, Greece, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Italy, Ivory Coast, Kiribati, Mauritania, Madagascar, Malta, Mauritius, Salomon Islands, Seychelles, Săo Tome and Principe, Portugal, Senegal, Spain, Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

14.

Cammilleri G., Vazzana M., Arizza V., Giunta F., Vella A., Lo Dico G., Giaccone V., Giofrè S.V., Giangrosso G., Cicero N., Ferrantelli V., 2017. Mercury in fish products: What’s the best for consumers between blue tuna and yellow tuna? Nat. Prod. Res. 32, 457–462.

-

i.

Heavy metals, mercury, Hg, muscle, bioaccumulation, food safety, mercury direct analyser, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

15.

Catanese G., 2006. Caracterización de las poblaciones de melva (Auxis spp) por métodos de biología molecular y diferenciación frente a otras especies de túnidos. Thesis, Departamento de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular Universidad de Cordoba: 1–136.

-

i.

Species discrimination, genetic analyses, mDNA, nDNA, clusters, Scombridae family, bullet tuna, Auxis rochei, frigate tuna, Auxis thazard, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, Atlantic little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

16.

Catanese G., Infante C., Manchado M., 2008. Complete mitochondrial DNA sequences of the frigate tuna Auxis thazard and the bullet tuna Auxis rochei. DNA Sequence, 19:3, 159–166, https://doi.org/10.1080/10425170701207117.

-

i.

Genetic analyses, mDNA, phylogeny, mitogenome, mitotype, bullet tuna, Auxis rochei, frigate tuna, Auxis thazard, Andalucia, Spain, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

17.

Catarci C., 2005. The world tuna industry, an analysis of imports and prices and of their combined impact on catches and tuna fishing capacity. In: Bayliff W. H., de Leiva Moreno J. I., Majkowski J. (eds), Proceedings of Second Meeting of the Technical Advisory Committee of the FAO project Management of tuna fishing capacity: conservation and socio-economics, Madrid, Spain, 15–18 March, 2004: 235–278.

-

i.

Tuna industry, tuna trade, tuna import, tuna export, markets, prices, impact on wild stocks, tuna fishing capacity, tuna species, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii, Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, bigeye tuna Thunnus obesus, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, world oceans, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

18.

Collette B., Acero A., Amorim A.F., Boustany A., Canales Ramirez C., Cardenas G., Carpenter K.E., Chang S.-K., de Oliveira Leite Jr. N., Di Natale A., Die D., Fox W., Fredou F.L., Graves J., Guzman-Mora A., Viera Hazin F.H., Hinton M., Juan Jorda M., Minte Vera C., Miyabe N., Montano Cruz R., Masuti E., Nelson R., Oxenford H., Restrepo V., Salas E., Schaefer K., Schratwieser J., Serra R., Sun C., Teixeira Lessa R.P., Pires Ferreira Travassos P.E., Uozumi Y., Yanez E., 2011a. Thunnus albacares, Yellofin tuna. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T21857A9327139. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T21857A9327139.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

19.

Collette B., Di Natale A., Fox W., Juan Jorda M., Miyabe N., Nelson R., Sun C., Uozumi Y., 2011. Thunnus tonggol, Longtail tuna. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170351A6763691. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170351A6763691.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, longtail tuna, Thunnus tonggol, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

20.

Collette B., Acero A., Amorim A.F., Boustany A., Canales Ramirez C., Cardenas G., Carpenter K.E., Chang S.-K., Chiang W., de Oliveira Leite Jr. N., Di Natale A., Die D., Fox W., Fredou F.L., Graves J., Viera Hazin F.H., Hinton M., Juan Jorda M., Minte Vera C., Miyabe N., Montano Cruz R., Nelson R., Oxenford H., Restrepo V., Schaefer K., Schratwieser J., Serra R., Sun C., Teixeira Lessa R.P., Pires Ferreira Travassos P.E., Uozumi Y., Yanez, E., 2011b. Thunnus obesus, Bigeye tuna. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T21859A9329255. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T21859A9329255.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

21.

Collette B., Chang S.-K., Di Natale A., Fox W., Juan Jorda M., Miyabe N., Nelson R., Uozumi Y., Wang S., 2011c. Thunnus maccoyii, Southern bluefin tuna. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T21858A9328286. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T21858A9328286.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyi, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

22.

Collette B., Chang S.-K., Di Natale A., Fox W., Juan Jorda M., Miyabe N., Nelson R., 2011d. Scomberomorus commerson, Narrow-barred Spanish mackerel. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170316A6745396. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170316A6745396.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, narrow-barred Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus commerson, Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, Red Sea, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

23.

Collette B., Amorim A.F., Boustany A., Carpenter K.E., de Oliveira Leite Jr. N., Di Natale A., Fox W., Fredou F.L., Graves J., Viera Hazin F.H., Juan Jorda M., Minte Vera, C. Miyabe, N., Nelson R., Oxenford H., Teixeira Lessa R.P., Pires Ferreira Travassos P.E., 2011e. Scomberomorus brasiliensis, Serra Spanish mackerel. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170335A6753567. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170335A6753567.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, Serra Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus brasiliensis, western Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

24.

Collette B., Amorim A.F., Boustany A., Carpenter K.E., de Oliveira Leite Jr. N., Di Natale A., Fox W., Fredou F.L., Graves J., Viera Hazin F.H., Juan Jorda M., Minte Vera C., Miyabe N., Nelson R., Oxenford H., Teixeira Lessa R.P., Pires Ferreira Travassos P.E., 2011f. Scomberomorus regalis, Cero. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170327A6749725. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170327A6749725.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, cero, Scomberomorus regalis, western Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

25.

Collette B., Amorim A.F., Boustany A., Carpenter K.E., de Oliveira Leite Jr. N., Di Natale A., Fox W., Fredou F.L., Graves J., Viera Hazin F.H., Juan Jorda M., Minte Vera C., Miyabe N., Nelson R., Oxenford H., Teixeira Lessa R.P., Pires Ferreira Travassos P.E., 2011 g. Scomberomorus cavalla, king mackerel. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170339A6755835. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170339A6755835.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, king mackerel, Scomberomorus cavalla, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

26.

Collette B., Amorim A.F., Boustany A., Carpenter K.E., de Oliveira Leite Jr. N., Di Natale A., Fox W., Fredou F.L., Graves J., Viera Hazin F.H., Juan Jorda M., Minte Vera C., Miyabe N., Nelson R., Oxenford H., Teixeira Lessa R.P., Pires Ferreira Travassos P.E., 2011 h. Scomberomorus tritor, West African Spanish mackerel. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170326A6749128. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170326A6749128.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, West African Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus tritor, eastern Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

27.

Collette B., Di Natale A., Fox W., Juan Jorda M., Nelson R., 2011i. Scomberomorus guttatus, Indian Spanish mackerel. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170311A6742170. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170311A6742170.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, Indian Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus guttatus, Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, western Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

28.

Collette B., Boustany A., Carpenter K.E., Di Natale A., Fox W., Graves J., Juan Jorda M., Kada O., Nelson R., Oxenford H., 2011j. Orcynopsis unicolor, Plain bonito. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170319A6746129. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170319A6746129.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, plain bonito, Orcynopsis unicolor, Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

29.

Collette B., Acero A., Canales Ramirez C., Cardenas G., Carpenter K.E., Di Natale A., Guzman-Mora A., Montano Cruz R., Nelson R., Schaefer K., Serra R., Yanez E., 2011 k. Sarda chiliensis, Pacific bonito. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170352A6763952. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170352A6763952.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, eastern Pacific bonito, Sarda chiliensis, eastern Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

30.

Collette B., Acero A., Canales Ramirez C., Cardenas G., Carpenter K.E., Chang S.-K., Di Natale A., Fox W., Guzman-Mora A., Juan Jorda M., Miyabe N., Montano Cruz R., Nelson R., Salas E., Schaefer K., Serra R., Uozumi Y., Yanez E., 2011 l. Sarda orientalis, Oriental bonito. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170313A6743337. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170313A6743337.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, oriental bonito, striped bonito, Sarda orientalis, eastern Pacific Ocean, western Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

31.

Collette B., Acero A., Amorim A.F., Boustany A., Canales Ramirez C., Cardenas G., Carpenter K.E., de Oliveira Leite Jr. N., Di Natale A., Die D., Fox W., Fredou F.L., Graves J., Guzman-Mora A., Viera Hazin F.H., Hinton M., Juan Jorda M., Kada O., Minte Vera C., Miyabe N., Montano Cruz R., Nelson R., Oxenford H., Restrepo V., Salas E., Schaefer K., Schratwieser J., Serra R., Sun C., Teixeira Lessa R.P., Pires Ferreira Travassos P.E., Uozumi Y., Yanez E., 2011 m. Acanthocybium solandri, Wahoo. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170331A6750961. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170331A6750961.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, wahoo, Acanthocybium solandri, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

32.

Collette B., Acero A., Amorim A.F., Boustany A., Canales Ramirez C., Cardenas G., Carpenter K.E., de Oliveira Leite Jr. N., Di Natale A., Fox W., Fredou F.L., Graves J., Guzman-Mora A., Viera Hazin F.H., Juan Jorda M., Kada O., Minte Vera C., Miyabe N., Montano Cruz R., Nelson R., Oxenford H., Salas E., Schaefer K., Serra R., Sun C., Teixeira Lessa R.P., Pires Ferreira Travassos P.E., Uozumi Y., Yanez E., 2011n. Katsuwonus pelamis, Oceanic bonito. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: e.T170310A6739812. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T170310A6739812.en.

-

i.

Conservation status, status assessment, red list, IUCN, fishery, data, Oceanic bonito, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

33.

Dagorn L., Bach P., Robinson J., Deneubourg J.L., Moreno G., Di Natale A., Tserpes G., Travassos P., Dufossé L., Taquet M., Robin J.J., Valettini B., Afonso J., Koutsikopoulos C., 2008. MADE: Preliminary information on a new EC project to propose measures to mitigate adverse impacts of open ocean fisheries targeting large pelagic fish. IOTC, WPEB, 14: 1–12.

-

i.

FAD fishery, longline fishery, electronic tagging, impact mitigation, alternative baits, swordfish fishery, Xiphias gladius, tropical tunas, pelagic sharks, by-catch, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

34.

Dagorn L., Bach P., Robinson J., Deneubourg J.L., Moreno G., Di Natale A., Tserpes G., Travassos P., Dufossé L., Taquet M., Robin J.J., Valettini B., Afonso J., Koutsikopoulos C., 2009. MADE: Preliminary information on a new EC project to propose measures to mitigate adverse impacts of open ocean fisheries targeting large pelagic fish. SCRS/2008/194, Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap., ICCAT, 64 (7): 2318–2533.

-

i.

FAD fishery, longline fishery, electronic tagging, impact mitigation, alternative baits, swordfish fishery, Xiphias gladius, tropical tunas, pelagic sharks, by-catch, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

35.

Dagorn L., Bach P., Robinson J., Deneubourg J.L., Moreno G., Di Natale A., Tserpes G., Travassos P., Dufossé L., Taquet M., Robin J.J., Valettini B., Afonso J., Koutsikopoulos C., 2013. Mitigating Adverse Ecological Aspects in Open Ocean Fisheries. Project 210496, 7th FP, final report to the European Commission. http://cordis.europa.eu/result/rcn/149406_en.html.

-

i.

FAD fishery, longline fishery, electronic tagging, impact mitigation, alternative baits, swordfish fishery, Xiphias gladius, tropical tunas, pelagic sharks, by-catch, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

36.

Da Rodda F., 2014. Il pesce del popolo, i popoli del pesce. Storia, cultura ed economia della pesca e del consumo del tonno nel Mondo. Thesis. Corso di Laurea in Scienze e Cultura della Gastronomia e della Ristorazione. Dipartimento di Agronomia, Animali, Alimenti, Risorse naturali ed Ambiente, Università degli Studi di Padova: 1–87.

-

i.

Commercial tunas, biology, history, prehistorical times, Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Middle Ages, modern age, industrial fishery, fishing technologies, fishery evolution, economy, markets, fishing capacity, IUU, RFMOs, stock, tuna industry, Japanese markets, certifications, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, blackfin tuna, Thunnus atlanticus, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyi, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis, long tailed tuna, Thunnus tonggol, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

37.

Del Caro A., Franco M.A., Sferlazzo G., Serra A., Menghini V., 1991. Approccio statistico multivariato nella discriminazione mediante parametri chimici di tonni di sesso diverso. Riv. Merceolog., 30 (3): 183–192.

-

i.

Multivariate statistical methods, PCA, QDA, frozen tuna, atomic absorption spectrometry, analyses, heavy metals, Mg, K, Cu, Fe, Na, Mn, Ca, proteins, fat, weight/length correlation, sex discrimination, yellowfin tuna, Neothynnus albacora, Thunnus albacares, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

38.

Del Caro A., Franco M.A., Sferlazzo G., Serra A., Menghini V., 1994. Analisi chemiometrica di tonni di diversa taglia e specie. Atti XVI Congresso Nazionale di Merceologia, Università di Pavia: 343–350.

-

i.

Multivariate statistical methods, PCA, frozen tuna, atomic absorption spectrometry, analyses, heavy metals, Mg, K, Cu, Fe, Na, Mn, Ca, proteins, fat, length frequencies, weight frequencies, weight/length correlation, dorsal muscle, tropical tunas, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

39.

De Metrio G., Corriero A., Deflorio M., 2006. Migration and spawning of northern bluefin tuna Thunnus thynnus thynnus. Comparison with two other subspecies Thunnus thynnus orientalis, Thunnus maccoyii. Aqua 2006, Conference of the World Aquaculture Society, Florence, 10–13 May 2006, Book of Abstracts: 1 p.

-

i.

Migrations, spawning, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis, Southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii, Mediterranean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

40.

De Metrio G., Deflorio M., Mylonas C.C., Bridges C.R., Vassallo-Agius R., Gordin H., Caggiano M., Caprioli R., Santamaria N., Zupa R., Pousis C., Di Gioia T., Losurdo M., Spedicato D., Corriero A., 2009. The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna Spawning In Captivity. Sustainable Aquaculture of the Bluefin and Yellowfin Tuna. Closing the Life Cycle for Commercial Production, December 1–2, 2009. SARDI, Adelaide, Australia, Book of Abstracts: 1p.

-

i.

Spawning, sexual maturation, captive breeding, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Mediterranean Sea, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

41.

Diaha N.C., Zudaire I., Chassot E., Pecoraro C., Bodin N., Amandè M.J., Dewals P., Romeo M.U., Irié Y.D., Barryga B.D., Gbeazere D.A., Kouaidio D., 2015. Present and future of reproductive biology studies of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap., ICCAT, 71: 489–509.

-

i.

Reproductive biology, sex ratio, spawning season, fish conditions, gonads, stomach content analyses, trophic chain, energy allocation, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Abijan, Ivory Coast, West Africa, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

42.

Diaha N.C., Zudaire I., Chassot E., Barrigah B.D., Irié Y.D., Gbeazere D.A., Kouadio D., Pecoraro C., Romeo M.U., Murua H., Amandè M.J., Dewals P., Bodin N., 2016. Annual monitoring of reproductive traits of female yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) in the eastern Atlantic Ocean. Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap., ICCAT, 72: 534–548.

-

i.

Reproductive behaviour, sex ratio, sexual maturity, condition index, gonadosomatic index, hepatosomatic index, length–weight relationship, histological analyses, oocyte sizes, length at 50% maturity, fecundity, spawning seasonality, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

43.

Di Marco Pisciottano I., Mita D.G., Gallo P., 2020. Bisphenol A, octylphenols and nonylphenols in fish muscle determined by LC/ESI–MS/MS after affinity chromatography clean up. Food Additives and Contaminants Part B, 13 (2): 139–147.

-

i.

Analytical methodology, bisphenol A, 4-octylphenol, 4-tertoctylphenol, 4-nonylphenol and tert-nonylphenol, liquid chromatography, mass spectrometer, fish muscle tissue, contaminants, seafood safety, custom controls, trade, import, fish species, sharks, cod, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Italy.

-

i.

-

44.

Di Natale A., 1989. Progetto integrato per lo sviluppo della pesca e della commercializzazione del pescato nella Repubblica di Djibouti. C.I.C. S.p.A., Roma. Report to Ministero degli Affari Esteri, Direzione Generale per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo: 1–187.

-

i.

International cooperation, coastal fisheries, small-scale fisheries, coastal planning, census, fishermen villages, ports, shipyards, social problems, economic problems, infrastructures, fish trade, export, social problems, economic problems, fish consumption, fish market, fishing gears, hand lines, troll lines, gillnets, longlines, bottom traps, lobster fishery, crab fishery, lagoon fisheries, demersal species, tropical tunas, Djibouti, Indian Ocean, Red Sea.

-

i.

-

45.

Di Natale A., 2020. The Italian annotated bibliography on tropical tunas. SCRS/2020/113, Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap., ICCAT, 77 (8): 1–17.

-

i.

Annotated bibliography, Italian authors, keywords, biology, reproduction, feeding, analytical techniques, behaviour, history, traditions, fisheries, catches, fishery techniques, fishing gears, technology, systematics, impact, rules, laws, privileges, nomenclature, economy, ethnography, anthropology, culture, food habits, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, narrow-barred Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus commerson, West African Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus tritor, serra Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus brasiliensis, Cero, Scomberomorus regalis, wahoo, Acanthocybium solandri, Indian mackerel, Rastelliger kanagurta, black skipjack, Euthynnus lineatus, king mackerel, Scomberomorus cavalla, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii, longtail tuna, Thunnus tonggol, eastern Pacific bonito, Sarda chilensis, Italy, Mediterranean Sea, Tropical Oceans, Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

46.

Di Natale A., Rotta G., Rainero E., 1993. Interactions of Pacific Tuna Fisheries. FAO-IED Cooperative Research. Informative Booklet: 8 p.

-

i.

Research programmes, FAO, IED, fishery interactions, species identification, conflicts, fishermen, fisheries, small-scale fisheries, coastal fisheries, purse-seine fishery, bait boat fishery, longline fishery, gillnet fishery, troll line fishery, tropical tunas, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyi, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis, long tailed tuna, Thunnus tonggol, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, Eastern Pacific bonito, Sarda chiliensis, frigate tuna, Auxis thazard, kawakawa, Euthynnus affinis, Pacific islands, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

47.

Di Natale A., Srour A., Hattour A., Keskin Ç., Idrissi M., Orsi Relini L., 2008. Regional study on small tunas in the Mediterranean including the Black Sea. GFCM-FAO, Studies and Reviews, 85: 1–150.

-

i.

Distribution, biology, reproduction, ecology, fishery, long-line fishery, driftnet fishery, purse-seine fishery, hand-line fishery, alien species, Atlantic bonito, Sarda sarda, bullet tuna, Auxis rochei, Atlantic little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, plain bonito, Orcynopsis unicolor, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, narrow-barred Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus commerson, wahoo, Acanthocybium solandri, Indian mackerel, Rastrelliger kanagurta, West African Spanish mackerel, Scomberomorus tritor, black skipjack, Euthynnus lineatus, dogtooth tuna, Gymnosarda unicolor, king mackerel, Scomberomorus cavalla, Spain, France, Italy, Malta, Slovenia, Croatia, Albania, Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, Lebanon, Syria, Israel, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco, Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea.

-

i.

-

48.

Galli L.J.G., Shiels H.A., Brill R.W., 2009. Temperature Sensitivity of Cardiac Function in Pelagic Fishes with Different Vertical Mobilities: Yellowfin Tuna (Thunnus albacares), Bigeye Tuna (Thunnus obesus), Mahimahi (Coryphaena hippurus), and Swordfish (Xiphias gladius). Physiological and Biochemical Zoology, 82, (3): 280–290.

-

i.

Fish heart, temperature sensitivity, temperature decrease, ventricular response, kinetic parameters, ryanodine, thapsigargin, SR inhibition, adrenaline, fish physiology, vertical mobility, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, dolphinfish, Coryphaena hippurus, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

49.

Ghirardelli E., 1981. La vita nelle acque – Tonno, sgombri e pescespada. Il nostro Universo. UTET, Torino: 1–626.

-

i.

Biology, distribution, reproductive biology, history, migrations, growth, diet, oceanography, thermal fronts, thermocline, fishery, tuna trap fishery, harpoon fishery, longline fishery, purse-seine fishery, Scomberomoridae, Thunnidae, Xiphidae, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, Atlantic little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, frigate tuna, Auxis thazard, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, Mediterranean spearfish, Tetrapturus belone, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean, Polar Oceans.

-

i.

-

50.

Gilman E., Clarke S., Brothers N., Alfaro-Shigueto J., Mandelman J., Mangel J., Petersen S., Piovano S., Thomson N., Dalzell P., Donoso M., Goren M., Werner T., 2007. Shark Depredation and Unwanted Bycatch in Pelagic Longline Fisheries: Industry Practices and Attitudes, and Shark Avoidance Strategies, Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council: Honolulu, Appendix 4: 100–110.

-

i.

Longline fishery, pelagic fishery, fleets, gear characteristics, by-catch, sharks depredation, catch rates, fishery management, regulation, environmental impact, economy, ecological interaction, social problems, industry attitudes, sharks deterrents, injuries, pelagic sharks species, blue shark, Prionace glauca, whiskery shark, Furgaleus macki, school grey shark, Galeorhinus galeus, hardnose houndshark, Mustelus mosis, gummy shark, Mustelus antarcticus, sharptooth smooth-hound, Mustelus dorsalis, dusky whaler shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, bronze whaler shark, Carcharhinus brachyurus, tiger shark, Galeocerdo cuvier, black tip shark, Carcharhinus tilstoni, ocanic whitetip shark, Carcharhinus longimanus, silky shark, Carcharhinus falciformis, spot-tail Carcharhinus sorrah, night shark, Carcharhinus signatus, dusky shark, Carcharhinus obscurus, Zambesi shark, Carcharhinus leucas, sandbar shark, Carcharhinus plumbeus, porbeagle, Lamna nasus, shortfin mako, Isurus oxyrinchus, longfin mako shark, Isurus, paucus, bigeye thresher shark, Alopias superciliosus, thresher shark, Alopias vulpinus, great hammerhead shark, Sphyrna mokarran, smooth hammerheard shark, Sphyrna zygaena, scalloped hammerhead shark, Sphyrna lewini, cookie-cutter shark, Isistius brasilensis, crocodile shark, Pseudocarcharias kamoharai, bigeye sixgill shark, Hexanchus nakamurai, soupfin shark, Galeorhinus galeus, ghost shark, Callorhinchus millii, dolphin fish, mahimahi, Coryphaena hippurus, opah, Lampris guttatus, escolar, Lepidocybium flavobrunneum, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, striped marlin, Kajikia audax, shortbill spearfish, Tetrapturus angustirostris, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, wahoo, Acanthocybium solandri, Australia, Chile, Fiji, Italy, Japan, Peru, South Africa, Hawaii, USA, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean Sea, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

51.

Greco N., Di Natale A., Pederzoli A., Severini P., 1989. Progetto integrato per lo sviluppo della pesca nel Faritany di Toulear (Madagascar). T.P.L. S.p.A., Roma. Report to Ministero degli Affari Esteri, Direzione Generale per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo, 2 vol.: 1–62, 1–240.

-

i.

International cooperation, coastal fisheries, small-scale fisheries, coastal planning, census, fishermen villages, ports, shipyards, infrastructures, fish trade, export, social problems, economic problems, fish consumption, food security, fishing gears, hand lines, troll lines, gillnets, longlines, bottom traps, shrimp fishery, lobster fishery, crab fishery, lagoon fisheries, demersal species, tropical tunas, Toulear, Madagascar, Mozambique Channel, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

52.

Infante C., Catanese G., Ponce M., Manchado M., 2004. Novel method for the authentication of frigate tunas (Auxis thazard and Auxis rochei) in commercial canned products. J. Agr. Food Chem., 52: 7435–7443.

-

i.

Species discrimination, molecular tools, canned tuna, genetic analyses, mDNA, cytochrome B, ATPase 6, frigate tuna, Auxis thazard, bullet tuna, Auxis rochei, Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

53.

Longo S., 2011. Global sushi: the political economy of the Mediterranean bluefin tuna fishery in the modern era. American Sociological Association, XVII (2): 403–427. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282529250_Global_Sushi_The_Political_Economy_of_the_Mediterranian_Bluefin_Tuna_Fishery_in_the_Modern_Era

-

i.

International tuna trade, history, social sciences, political economy, tuna fishery, industrial fishery, longline fishery, purse-seine fishery, tuna traps, tuna ranching, tuna farms, global markets, export, fresh tuna, frozen tuna, tuna consumption, food habits, sushi, sashimi, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii, Italy, Turkey, Malta, Croatia, France, Spain, Tunisia, Mediterranean Sea, Japan, United States of America.

-

i.

-

54.

Malvarosa L., De Young C., 2010. Fish trade among Mediterranean countries: intraregional trade and import–export with the European Union. Studies and Reviews. General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean, Rome, FAO, 86: 1–93.

-

i.

Fish trade, import, export, regulations, European Union, Mediterranean Countries, standards, trade agreements, fishery production, fish consumption, trade flows, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, plain bonito, Orcynopsis unicolor, Atlantic little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, pacific Ocean, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

55.

Manfredi G., 2018. Callipo dal 1913. La storia, gli uomini, il mare. Rubbettino Edit., Soveria Mannelli: 1–207.

-

i.

Dynasty, history, iconography, architecture, buildings, trap fishery, beach seine, purse-seine fishery, dictionary, vessels, Rais, fishermen, workers, traditions, songs, rhythms, cialoma, fishery industry, canning industry, canning in oil, packaging, marketing, salted eggs, bottarga, salted male gonads, lattume, seafood, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Tonnara della Seggiola, Tonnara Marchese Gagliardi, Tonnara Sant’Irene, Tonnara Grande, Pizzo Calabro, Briatico, Calabria, Italy, Tyrrhenian Sea, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

56.

Manzoni P., 1987. Enciclopedia illustrata delle specie ittiche marine di interesse commerciale aventi denominazione stabilita dalla normativa italiana. Ist. Geogr. De Agostini, Novara: 1–127.

-

i.

Official Italian fish names, nomenclature, systematic, distribution, description, morphology, colour, photos, commercial characteristics, salted ovaries, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii, longtail tuna, Thunnus tonggol, skipjack tuna, Euthynnus pelamis, Katsuwonus pelamis, bullet tuna, Auxis rochei, frigate tuna, Auxis thazard, Atlantic little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, kawakawa, Euthynnus affinis, black skipjack, Euthynnus lineatus, Atlantic bonito, Sarda sarda, Mediterranean spearfish, Tetrapturus belone, Atlantic white marlin, Tetrapturus albidus, Kajikia albida, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

57.

Marrone R., Mascolo C., Palma G., Smaldone G., Girasole M., Anastasio A., 2015. Carbon monoxide residues in vacuum-packed yellowfin tuna loins (Thunnus albacares). Italian Journal of Food Safety, 4: 142–144. https://www.pagepressjournals.org/index.php/ijfs/article/view/ijfs.2015.4528/4823

-

i.

Spectrographic analyses, spectrophotometric method, carbon monoxide, shell life, packaging, loins, import, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Italy, Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

58.

Michelini E., Cevenini L., Mezzanotte L., Simoni P., Baraldini M., De Laude L., Roda A., 2007. One-Step Triplex-Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for the Authentication of Yellowfin (Thunnus albacares), Bigeye (Thunnus obesus), and Skipjack (Katsuwonus pelamis) Tuna DNA from Fresh, Frozen, and Canned Tuna Samples. J. Agric. Food Chem., 55: 7638–7647. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jf070902k

-

i.

Species identification; genetic analyses, triplex-PCR; mitochondrial cytochrome b gene; misdescription of tuna products; canned tuna, tuna in oil, tuna labelling, food forensics, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, Italy, tropical Oceans.

-

i.

-

59.

Moore B.R., Adams T., Allain V., Bell J.D., Bigler M., Bromhead D., Clark S., Davies C., Evans K., Faasili U.Jr, Farley J., Fitchett M., Grewe P.M., Hampton J., Hyde J., Leroy B., Lewis A., Lorrain A., Macdonald J.I., Marie A.D., Minte-Vera C., Natasha J., Nicol S., Obregon P., Peatman T., Pecoraro C., Phillip N.B.Jr, Pilling G.M., Rico C., Sanchez C., Scott R., Scutt Phillips J., Stockwell B., Tremblay-Boyer L., Usu T., Williams A.J., Smith N., 2020. Defining the stock structures of key commercial tunas in the Pacific Ocean II: Sampling considerations and future directions. Fisheries Research, 230, 105,524: 1–17.

-

i.

Stock structure, movements, migrations, spatial dynamics, biological sampling, sampling strategies, panmixia, isolation by distance, regional residency, spawning area fidelity, metapopulations, spawning, fisheries management, RFMOs, stock assessments, commercial fisheries, artisanal fisheries, subsistence fisheries, recreational fisheries, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, albacore tuna, Thunnus alalunga, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

60.

Ninni E., 1931. Relazione sulla campagna esplorativa di pesca nel Mar Rosso, Febbraio-Marzo 1929. Boll. Pesca, Piscic., Idrobiol., Roma, VII (2): 1–77.

-

i.

Experimental fishery, fishing trials, set nets, longline, hand line, seine net, boat seine, artisanal fisheries, regulations, fishing maps, sea products, fish industry, markets, export, pearls, mother-of-pearl, molluscs, demersal species, pelagic species, sharks, wahoo, Cybium verany, Acanthocybium solandri, narrow-barred Spanish mackerel, Cybium commersonii, Scomberomorus commerson, double-line mackerel. Thynnus bilineatus, Grammatorcynus bilineatus, billfish, Histiophorus sp., Somalia, Red Sea, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

61.

Ottolenghi F., Silvestri C., Lovatelli A., 2003. An overview of world bluefin tuna fishing and farming. In: Oray I.K., Karakulak F.S. (Eds.), Workshop on farming, management and conservation of bluefin tuna. Turkish Marine Research Foundation, Istanbul, 13: 1–9.

-

i.

Fishery, fishing gears, purse-sine fishery, catches, tuna farming, tuna fattening, farm production, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, Japan, Mexico, Australia, Canada, Spain, Malta, Croatia, Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

62.

Ottolenghi F., Cerasi S., Bertolino F., Binda F., De Metrio G., Orban E., Pagliara T., Pelusi P., Piccinetti C., Rambaldi E., Tičina V., Ugolini R., 2008. Il tonno rosso nel Mediterraneo. Biologia, Pesca, Allevamento e Gestione. UNIMAR, Roma: 1–141.

-

i.

History, research, fishery, management, traditions, biology, migration, reproduction, distribution, swimming behaviour, satellite tagging, farming, tuna farming, tuna fattening, environmental impact, fish meat quality, trading, aquaculture, artificial breeding, juveniles, growth, longline fishery, trap fishery, purse-seine fishery, longline fishery, trolling line fishery, hand line fishery, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis, Southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, Atlantic little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, Italy, Malta, Croatia, Mediterranean Sea, Japan, Australia, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

63.

Pappalardo A.M., Copat C., Ferrito V., Grasso A., Ferrante M., 2017. Heavy metal content and molecular species identification in canned tuna: Insights into human food safety. Molecular Medicine Report: 3430–3437. https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2017.6376

-

i.

Contaminants, heavy metals, mercury (HG), lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), bioaccumulation, toxicity, molecular species identification, misidentification, canned tuna, canned in oil, import, food safety, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, Italy.

-

i.

-

64.

Pavesi P., 1887. Le migrazioni del Tonno. Rendiconti dell’Istituto Lombardo di Scienze e Lettere, Milano, 2 (20): 311–324.

-

i.

Tuna migrations, currents, tuna biology, tuna reproduction, spawning areas, tuna trap fishery, synonyms, bluefin tuna, Thunnus brachypterus, Orcynus thynnus, Thynnus mediterraneus, Thunnus thynnus, yellowfin tuna, Thynnus albacore, Thunnus albacares, Atlantic little tuna, Thynnus brevipinnis, Euthynnus alletteratus, blackfin tuna, Thynnus coretta, Thunnus atlanticus, skipjack tuna, Thynnus pelamys, Katsuwonus pelamis, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

65.

Pecoraro C., 2014. Challenging the knowledge bio-based fisheries of tropical tuna stocks: assessing genomic population structure in yellowfin (Thunnus albacares). Front. Mar. Sci. Conference Abstract: IMMR | International Meeting on Marine Research 2014. https://doi.org/10.3389/conf.fmars.2014.02.00155

-

i.

Marine genomics, population genetics, population structure, genome-wide marker discovery, genotyping, next generation sequencing, DNA microsatellites, mitochondrial DNA, allozymes, SNPs, 2b-RAD sequencing, RFMOS, management, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

66.

Pecoraro C., 2016. Global population genomic structure and life history trait analysis of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares). Ph.D. Thesis, Biodiversità ed Evoluzione, Zoologia, Ciclo XXVIII, Alma Mater Studiorum, University of Bologna: 1–188.

-

i.

Genetic structure, 2b-RAD, genotyping technique, gene flow, genetic differentiation, inference, population genetics, de novo genome, SNPs, microsatellite loci, distribution area, management, canning industry, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Atlantic Ocean, eastern Pacific Ocean, western Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

67.

Pecoraro C., Babbucci M., Villamor A., Franch R., Papetti C., Leroy B., Ortega-Garcia S., Muir J., Rooker J., Arocha F., Murua H., Zudaire I., Chassot E., Bodin N., Tinti F., Bargelloni L., Cariani A., 2016. Methodological assessment of 2b-RAD genotyping technique for population structure inferences in yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares). Marine Genomics, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margen.2015.12.002.

-

i.

Genetic structure, 2b-RAD, genotyping technique, gene flow, genetic differentiation, inference, population genetics, de novo genome, SNPs, distribution area, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Atlantic Ocean, eastern Pacific Ocean, western Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

68.

Pecoraro C., Zudaire I., Bodin N., Murua H., Taconet P., Díaz-Jaimes P., Cariani A., Tinti F., Chassot E., 2017. Putting all the pieces together: integrating current knowledge of the biology, ecology, fisheries status, stock structure and management of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares). Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 27: 811–841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11160-016-9460-z.

-

i.

Fish biology, fish ecology, fisheries, stock status, stock structure, management, RFMOs, ICCAT, IATTC, IOTC, genetic structure, gene flow, distribution area, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Atlantic Ocean, eastern Pacific Ocean, western Pacific Ocean, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

69.

Pecoraro C., Babbucci M., Franch R., Papetti C., Chassot E., Bodin N., Cariani A., Bargelloni L., Tinti F., 2018. The population genomics of yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) at global geographic scale challenges current stock delineation. Nature Scientific Reports, 8: 13,890. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32331-3.

-

i.

SNPs, genetic differentiation, stock assessment, illegal trade monitoring, trade, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

70.

Pecoraro C., Crobe V., Ferrari V., Piattoni F., Sandionigi A., Andrews A.J., Cariani A., Tinti F., 2020a. Canning Processes Reduce the DNA-Based Traceability of Commercial Tropical Tunas. Foods, 9 (10), 1372: 1–15.

-

i.

DNA barcoding, cytochrome b, seafood mislabelling, traceability, species substitutions, seafood, DNA degradation, canning process, tuna industry, canned in oil, canned in brine, tropical tunas, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, longtail tuna, Thunnus tonggol, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

71.

Pecoraro C., Zudaire I., Galimberti G., Romeo M., Murua H., Fruciano C., Scherer C., Tinti F., Diaha N.C., Bodin N., Chassot E., 2020b. When size matters: The gonads of larger female yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) have different fatty acids profiles compared to smaller individuals. Fisheries Research, 232, 105,726: 1–7.

-

i.

Female gonads, fatty acids contents, correlation with size, size-dependent variation, analyses, spawning, reproduction, fecundity, recruitment pattern, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Gulf of Guinea, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

72.

Perosino S., 1963. La pesca. Istituto Geografico D’Agostini, Novara: 1–416.

-

i.

History, Prehistory, Egyptians, Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Middle Ages, trap fishery, longlines, hand lines, rod and reel, sport fishery, recreation fishery, migrations, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, Mediterranean spearfish, Tetrapturus belone, blue marlin, Makaira nigricans, Atlantic sailfish, Istiophorus albicans, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, Atlantic bonito, Sarda sarda, Atlantic little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean.

-

i.

-

73.

Piccinetti C., Dell’Osso G., Franceschi G., De Lorenzo S., Ricciardi F., 2006. L’Italia del pesce. Itinerari di Cultura Gastronomica. Accademia Italiana della Cucina, Grafica Giorgetti, Milano: 1–255.

-

i.

Geography, gastronomy, recipes, food habits, seafood, history, Romans, Arabs, Middle Ages, traditions, environment, migrations, fisheries, trawl fishery, tuna traps, longline fishery, purse-seine fishery, harpoon fishery, by-catch, aquaculture, salt plants, traditional culture, tuna trade, tuna industry, tuna in oil, salted tuna, canned tuna, tuna trade, tuna export, tuna import, garum, bottarga, fish, crustaceans, cephalopods, marine turtles, cetaceans, protected species, minimum size regulation, official nomenclature, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, bullet tuna, Auxis rochei, Atlantic bonito, Sarda sarda, Atlantic little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, bigeye tuna, Thunnus obesus, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, Mediterranean spearfish, Tetrapturus belone, Italy, Ligurian Sea, Tyrrhenian Sea, Sardinian Sea, Strait of Sicily, Strait of Messina, Ionian Sea, Adriatic Sea, Mediterranean Sea, tropical Oceans.

-

i.

-

74.

Pirati D., 1971. Le conserve di tonno. Stazione Sperimentale, per l’Industria delle Conserve Alimentari, Parma: 1–133.

-

i.

Systematics, nomenclature, fishery, trap fishery, longline fishery, purse seine, line fishery, industry, canning, sanitary aspects, health, hygiene, nutritional values, quality control, recipes, pet food, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, Albacora, Thunnus albacares, Neothunnus macropterus, bigeye, Thunnus obesus, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, Germo alalunga, skipjack tuna, Katsuwonus pelamis, kawakawa, Euthynnus affinis, Euthynnus yaito, black skipjack, Euthynnus lineatus, little tunny, Euthynnus alletteratus, frigate tuna, Auxis thazard, Atlantic mackerel, Scomber scombrus, Atlantic bonito, Sarda sarda, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean, Mediterranean Sea.

-

i.

-

75.

Premi C.B., 1884. Consumo del pesce salato in Italia. Il progetto d’aumento del dazio sul tonno estero. Tip. Ciminago, Genova: 1–64.

-

i.

Salted fish consumption, markets, commerce, food habits, salted tuna, tuna trap fishery, custom rights, custom duties, import taxes, tuna trade, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, tropical tunas, Italy, Spain, Mediterranean Sea, tropical Oceans.

-

i.

-

76.

Quilici F. (ed.), 1979. Grande enciclopedia del Mare. Armando Curcio Editore, Bergamo, 8 volumes: 1–3078.

-

i.

Sea culture, traditions, history, Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, myths, images, fishermen, villages, marine fauna, behaviour, biology, migrations, fisheries, longline fishery, harpoon fishery, driftnet fishery, trap fishery, small traps, hand lines, recreational fishery, coral fishery, sponge fishery, diving, fishing vessels, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, albacore, Thunnus alalunga, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, Mediterranean spearfish, Tetrapturus belone, Atlantic sailfish, Istiophorus albicans, Indo-Pacific sailfish, Istiophorus platypterus, billfish species, Sicily, Sardinia, Italy, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

77.

Russo R., Lo Voi A., De Simone A., Serpe F.P., Anastasio A., Pepe T., Cacace D., Severino L., 2013. Heavy metals in canned tuna from Italian markets. J. Food Prot., 76: 355–359. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-346.

-

i.

Contaminants, xenobiotic, atomic absorption spectrometry, heavy metals, mercury (Hg), lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), food quality, food safety, product monitoring, market, tuna industry, canned tuna in oil, metal cans, glass jars, tropical tunas, Italy.

-

i.

-

78.

Scarpato D., Simeone M., 2005. La filiera del tonno rosso mediterraneo: problematiche e prospettive del comparto in Campania. Istituto di Studi Economici, Università degli Studi di Napoli “Parthenope”. Working paper, 4: 1–20.

-

i.

Fishery, purse-seine fishery, tuna chain, trade, tuna farming, fleet, socio-economy, market perspectives, import, export, Japanese market, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, southern bluefin tuna, Thunnus maccoyii, Pacific bluefin tuna, Thunnus orientalis, Campania, Italy, Tyrrhenian Sea, Mediterranean Sea, Pacific Ocean, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

79.

Scordia C., 1937. Sulle denominazioni da scriversi sulle scatole dei tonniformi conservati sott’olio. Boll. Ist. Zool., R. Univ. Messina, 12: 1–5.

-

i.

Canned tuna, official species name, commercial names, nomenclature, tuna trade, bluefin tuna, tonno, Thunnus thynnus, albacore, alalunga, Thunnus alalunga, Germo alalunga, Atlantic little tunny, tonnetto, Euthynnus alletteratus, tonno extra, bigeye, Thunnus obesus, Parathunnus obesus, albacora, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Neothunnus albacora, Neothunnus macropterus, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

80.

Sferlazzo G., Franco M.A., Del Caro A., Madau M.E., Cristini A., Menghini V., 1995. Discrimination of tuna (Neothynnus albacora) fishing-sites using chemical parameters elaborated by multivariate statistical techniques – Ital. J. Food Sci., 4: 395–402.

-

i.

Stock characteristics, area discrimination, frozen tuna, atomic absorption spectrometry, analyses, heavy metals, Mg, K, Cu, Fe, Na, Mn, Ca, proteins, fat, weight/length correlation, multivariate analysis, yellowfin tuna, Neothynnus albacora, Thunnus albacares, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

81.

Smulevich G., Droghetti E., Focardi C., Coletta M., Ciaccio C., Nocentini M., 2007. A rapid spectroscopic method to detect the fraudulent treatment of tuna fish with carbon monoxide. Food Chem 101:1071–7.

-

i.

Myoglobin-CO complex, electronic absorption, second derivative, fraudulent treatment, carbon monoxide, food safety, seafood trade, yellowfin tuna, Thunnus albacares, Indonesia, Indian Ocean.

-

i.

-

82.

Storelli M.M., Barone G., Cuttone G., Giungato D., Garofalo R., 2010. Occurrence of toxic metals (Hg, Cd and Pb) in fresh and canned tuna: Public health implications. Food Chem. Toxicol., 48 (11): 3167–3170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2010.08.013.

-

i.

Contaminants, heavy metals, mercury (Hg), lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), tuna quality, fresh tuna, canned tuna, tuna industry, import, health risks, food safety, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, tropical tunas, Italy, Mediterranean Sea, tropical Oceans.

-

i.

-

83.

Storelli M.M., Normanno G., Barone G., Dambrosio A., Errico L., Garofalo R., Giacominelli-Stuffler R., 2012. Toxic metals (Hg, Cd, and Pb) in fishery products imported into Italy: suitability for human consumption. J. Food Prot., 75 (1): 189–194. https://doi.org/10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-212.

-

i.

Contaminants, heavy metals, mercury (Hg), lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), toxicity, market, import, food safety, crustaceans, molluscs, fish species, longtail tuna, Thunnus tonggol, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, Italy, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, tropical Oceans.

-

i.

-

84.

Valsecchi A., 1990. Relazione sulla situazione del settore della trasformazione e commercializzazione dei prodotti ittici. Atti Conferenza Nazionale della Pesca, 14–15 July 1990, Bari: 45–68.

-

i.

Industry, conserves, economy, marketing, strategy, production, trade, import, export, workers, fish species, molluscs, tunas, anchovies, products, canned products, tuna in oil, salted products, smoked products, marinated products, frozen products, fish quality, new technologies, fish markets, management, tropical tunas, bluefin tuna, Thunnus thynnus, swordfish, Xiphias gladius, Italy, Mediterranean Sea, Atlantic Ocean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Ocean.

-

i.

-

85.

Valsecchi A., 2014. The European Consumer market. Driving commodity into a value added product. 1st African Tuna Conference, 25–26 September2014. Book of Abstracts: 40 p.

-

i.