Abstract

Although the Yo Sí Puedo! method for adult literacy education has been in use in many countries and received a Unesco Literacy Prize, this article highlights the need to question one of its crucial elements. Yo Sí Puedo! was developed in Cuba and later on implemented in mass literacy campaigns in many other, mainly developing, countries. One of them is Timor-Leste (East Timor), a multilingual country in South-East Asia that became independent in 2002. Here, Yo Sí Puedo! was in use in adult literacy education in 2007–2012, next to other literacy programmes.

After an introduction to the historical changes in language policy in multilingual Timor-Leste and how they affected literacy education, we will present a study on adult literacy acquisition that was conducted in Timor-Leste between 2009 and 2014 (Boon, 2014). In a broad study the results of several adult literacy programmes and the factors that impacted the adults’ literacy skills were investigated and evaluated. An in-depth study with classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers shed further light on the literacy teaching practices, the uses and values of literacy and the ideas that guided teachers’ practices.

The paper will focus on the adult literacy programme that was introduced by Cuban educators, first in Portuguese and subsequently in Tetum. We will compare the method of this programme, that associates numbers and letters, with other programmes and present some results of the broad study on literacy abilities. Classroom observations show how the Yo Sí Puedo! method was applied in some adult literacy classes, and whether it helped adults to acquire the alphabetic principle, which is crucial to build further reading and writing ability. Although this method was awarded for being innovative and successful, our data demonstrate less reason for optimism.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Most research on literacy teaching and acquisition has been done with children in highly literate, western societies in the context of formal education and in bureaucratic environments (Kurvers, 2002; Morais & Kolinsky, 1995; Purcell-Gates, 1999). Research on adults learning to read and write in a second language has mostly been done with immigrants in the literate environment of their new country (Van de Craats et al., 2006). This only partially covers the contexts in which many adults become readers and writers (Wagner, 2004). In many countries, adults acquire literacy in a second language in multilingual contexts and outside compulsory formal education. This is the case in Timor-Leste where, since 2002, many adults have been building initial reading and writing skills in a second language (often Tetum).

The Democratic Republic Timor-Leste, a young nation in Southeast Asia, has a history of multilingualism, which is reflected in its consecutive language policies. A large number of indigenous languages are spoken in different regions of the country; estimates of the number range from 20 (Ethnologue, 2019) to 32 (CIA, 2019), depending on the defining criteria about what counts as a distinct language. These indigenous languages are often the first languages learned by the people born in those regions. From the sixteenth century until late 1975, the eastern part of the island of Timor had been a colony of Portugal. Portuguese was imposed as a colonial language and the only language of education and in governmental institutions. On the 28th of November 1975, Timor-Leste declared itself independent from Portugal, but was invaded by Indonesia 9 days later, which incorporated it as a province. The occupation by Indonesia lasted until 1999. The Indonesian language was imposed as the sole medium of instruction in schools (Cabral, 2013), although the use of Tetum spread widely, as a lingua franca and as the language used by the Roman Catholic Church. In the resistance, Tetum and Portuguese were used as languages of literacy education. In 1999 an overwhelming majority voted for independence in a UN-supervised popular referendum. In May 2002, Timor-Leste restored its independence. Timor-Leste’s 2002 Constitution declared Tetum and Portuguese as official languages, recognized a number of ‘national languages’ to be further developed by the state, and accepted Indonesian and English as ‘working languages’ (RDTL, 2002).

Language-in-education policies since 2002 show several changes regarding the proportion of time devoted to Tetum and Portuguese as languages of instruction. Quinn (2013) noted that in the 2004 Education Policy Portuguese was given precedence and Tetum was referred to as ‘pedagogic aide’, while in later policies, the use of Tetum was given greater emphasis. In the National Education Strategic Plan 2011–2030 (Ministry of Education, 2011a), the two official languages were presented as equal. In addition, in 2011 the Ministry of Education launched new policy guidelines on the use of children’s mother tongues as languages of teaching and learning in the 2 years of pre-primary education and as languages for initial literacy in grade 1 of primary education (Ministry of Education, 2011b).

Our research project, conducted between 2009 and 2014, investigated adult literacy education in the context of multilingualism and language in education policies in Timor-Leste. Estimations on adult literacy rates vary in different sources: UNDP’s, 2018 Human Development Index reported an adult literacy rate of 58.3% (ages 15 years and older) in 2006–2016. In the age group 15–24 years, the literacy rates were 78.6% among females and 80,5% among males. CIA’s World Factbook (2019) reported that, of the population of age 15 and over, 67.5% could read and write: 71.5% of the males and 63.4% of the females (2015 est.).

2 Approaches in Adult Literacy Teaching: An Overview

In this overview we focus on early reading and writing instruction to adults who never went to school and are learning to read and write for the first time in their life. A few principles are guiding in historical overviews of methods in teaching reading in general, and adult literacy in particular: emphasis on the code or on the meaning, on the material or the learner, and on the existence of different stages in the learning process.

William Gray (1969) conducted one of the first studies on beginning reading instruction. He and his colleagues investigated hundreds of materials that were used in teaching reading to beginning readers (children and adults). Their analysis revealed a classification of methods in two broad groups, the early specialized methods and the later more eclectic or learner-centered approaches.

The most important early specialized methods are the alphabetic or spelling methods, the phonic methods, and the syllabic methods. The spelling methods have been used all over the world for centuries. The basic idea is that learners start with learning the names of the letters in alphabetical order and then learn to combine these letter names into syllables and words. The phonic method used the sounds of the letters (not the letter names) as a starting point, the main advantage being the development of the ability to sound out the letters and to recognize the word by blending them. The syllabic method used the syllable as the key unit because pronouncing consonants accurately without adding a vowel was thought to be hardly possible. In teaching reading with this method, beginning readers start with learning the vowels and after that practice learning all syllables of the language in syllable strings. These three methods often are called synthetic methods, since they start from the meaningless linguistic units gradually building the larger whole of meaningful words and sentences, later often combined with mnemonic devices to help beginners memorize the letters and sounds, for example vivid illustrations of the shape of the letters (a snake for ‘s’ or a hoop for ‘o’) or the sounds (like the cry of an owl: ‘u’).

Methods that emphasize meaning consider meaningful language units as the starting point in early reading instruction, either words, phrases, sentences, or short stories. These units have to be learned by heart. In analytic methods, the meaningful units are then broken down into smaller, meaningless units (i.e., words into letters or syllables, phrases into words). This ‘breaking down’ is not done in global or look-say methods. To this latter category one could add the whole language approach (Goodman, 1986) that encourages readers to memorize meaningful words and then use context-cues to identify or ‘guess’ new words.

The early specialized methods differed in the language units in the first reading lessons and the basic mental processes involved (analysis, synthesis, or rote learning). Changes made over time were meant to overcome weaknesses in each of the approaches, leading to more and more diversification. The later eclectic methods combined the best of the analytic and synthetic methods, in taking carefully selected meaningful units which are subsequently analysed and synthesized right from the beginning. Often, they also pay more attention to reading comprehension.

The ‘learner-centered trend’ assumed that the interests, needs and previous experiences of the learner should be taken into account, both in content and in instructional method. Adult literacy classes often start with group discussions, awareness raising and developing reading matter that is based on the experiences of the adults. The late Paolo FreireFootnote 1 (Freire, 1970) became one of the most famous proponents of this approach, although Freire carefully investigated and developed key concepts (codifications) that both guided the cultural and political awareness of the learners, and their introduction to the written code. In some of these approaches the teaching of reading and writing is integrated into other parts of the curriculum, like in Celestin Freinet’s ‘centres of interest’, in which learning is based on real experiences and enquiry. Learner-centered methods, in which the reading materials are developed in cooperation with the learners, have since long been favourite in adult literacy education in many countries.

Liberman and Liberman (1990) and Chall (1999) also present overviews of teaching principles in beginning reading and writing, mainly focusing on children. Liberman and Liberman distinguish between methods that emphasize meaning and methods that emphasize the code, arguing that methods that emphasize meaning only (like the whole language approach) assume that learning to read and write is as natural as learning to speak and that the beginning reader only needs opportunities to engage with written language and a print-rich environment. The code emphasis methods (which Liberman and Liberman support) on the contrary assume that learning to read and write is not natural at all, because pre-readers do not have conscious access to the phonological make-up of the language they can already use. Beginning readers therefore need to be made aware of this phonological make-up (the alphabetic script is based on it) and need explicit instruction in the alphabetic principle (see also Kurvers, 2007).

Similar to Liberman and Liberman’s summary, Jeanne Chall (1999) based her models on how reading is first learned and how it develops. She distinguishes two major types of beginning reading instructions. One model views beginning reading as “one single process of getting meaning from print”, another views it as a two-stage process “concerned first with letters and sounds and then with meaning” (Chall, 1999:163). She notes that during the twentieth century reading instruction changed from following the two-stage model to reading as a one-stage process, directly from print to meaning. Since then, heated debates between proponents of the two approaches continued. Like Liberman and Liberman she observes that the one-stage model tends to see learning to read as a natural process, that does not require explicit attention to letters and sounds. The two-stage model assumes that learning to read is not natural, that it needs explicit instruction, particularly in the relationship between letters and sounds. Her studies revealed that learning to read needs explicit attention for the code, however not without attention for meaning making. In many methods for adults, the importance of relevance for daily life is stressed and research shows the impact of contextualization of teaching (Condelli & Wrigley, 2006; Kurvers & Stockmann, 2009).

3 Adult Literacy Education in Timor-Leste: Programmes and Results

3.1 Programmes

The study described in this paper was part of a larger research project on adult literacy in Timor-Leste that started in 2009 supported by NWO/WOTRO:Footnote 2 ‘Becoming a nation of readers in Timor-Leste: Language policy and adult literacy development in a multilingual context’ (see De Araújo e Corte-Real & Kroon, 2012). The project comprised three studies on adult literacy education in Timor-Leste. The first study investigated adult literacy education in the past, focusing on the years 1974–2002 (Cabral & Martin-Jones, 2012). The second study, reported on in this article, investigated learning to read and write in more recent adult literacy programmes that were implemented in the years after Independence (Boon, 2014). The third study investigated the position in adult literacy education of the regional language Fataluku (Da Conceição Savio et al., 2012).

The second study investigated how teachers and learners were working on different literacy goals in different programmes, the factors that impacted literacy acquisition by adults in the different programmes and the use of linguistic resources available to teachers and students (Blommaert, 2013) for communication in the classrooms while trying to reach those goals.

Two different programmes were in use. The first programme, Los Hau Bele, was the Tetum version of the Cuban programme Yo, Sí Puedo!, an audio-visual adult literacy programme that was developed in Cuba in the late 1990s and has been used in mass literacy campaigns in a range of countries in support of movements for social and political change (Boughton, 2010, 2012). The Cuban program aimed at self-actualisation, agency, critical thinking, acknowledging diversity and empowering people (Bancroft, 2008; Relys Díaz, 2013). The programme was adapted to be used in Timor-Leste, resulting first in the Sim Eu Posso version in Portuguese and later, when the use/implementation of the Portuguese version turned out to be too difficult, in the Los Hau Bele version in Tetum. Timorese facilitators were trained by Cuban advisors to deliver the programme to adult learners in Timor-Leste. Los Hau Bele became available in autumn 2008 and was used in all municipalities by mid-2009. The campaign finished late 2012. Different from all other adult literacy programmes we know of, literacy teaching in the Los Hau Bele programme is based on associating letters with numerals. The idea behind this method is the assumption that numbers are already familiar to adult literacy learners (Boughton, 2010), and that combining something familiar (a number) to something new (a letter) makes learning the letters easier (Relys Díaz, 2013; Bancroft, 2008; Filho, 2011). The programme consists of 65 video-lessons on DVDs, a 16-page learner workbook and a 20-page teacher manual (Boon, 2011; Boon & Kurvers, 2012). The teacher manual provides information about the programme and general guidelines on teaching and structuring lessons of about 5 h a week (for more details on the Los Hau Bele programme, see Sect. 4.1).

The second programme, Hakat ba Oin, applies an analytic-synthetic approach in which, starting with locally relevant and familiar themes and keywords (i.e., related to food, transport, tools), learners gradually learn the alphabetic principle by segmenting words into syllables and sounds, associating letters with sounds and blending the sounds again. When they have grasped the alphabetic principle, they can practice further reading and writing of simple phrases and very short texts. Hakat ba Oin consists of four books of 100 pages each, plus a 46-page teacher manual. The follow up Iha Dalan programme provides longer texts and exercises on relevant themes like ‘health’, ‘agriculture’, or ‘human rights’. The Hakat ba Oin and Iha Dalan programmes were developed in 2004–2005 Timor-Leste’s Ministry of Education, in collaboration with local and international NGOs and multilateral organisations (UNDP, Unicef, Unesco). The first materials were piloted in 2006–2007 and revised versions were implemented nationwide in 2007 (Hakat ba Oin) and 2008 (Iha Dalan), each programme to be used for around 6 months.Footnote 3

The Hakat ba Oin and Iha Dalan programmes were later compressed into one three-month course for young people in the Youth Employment Promotion (YEP) programme that was carried out by the Secretary of State for Professional Training and Employment in 2009–2011 and coordinated by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in collaboration with the Ministry of Education and with local NGOs.

3.2 Research Methods

Different research lenses were used in a broad study with a large number of people in eight of the country’s 13 districts and an in-depth study to obtain more detailed information on a smaller number of people. The broad study investigated the results after a first period of literacy teaching and the factors influencing growth in initial reading and writing ability, the classroom-based teaching practices and the uses and values of literacy of the learners in social domains such as work, leisure time, church, and home. Participants in the broad study were 100 teachers and 756 learners in 73 literacy groups. Of the 100 teachers, 54% were women. The teachers’ mean age was 33.80 years (SD 10.74), ranging from 19 to 66 years, and they averaged 10.65 years (SD 2.33) of education. Most lacked teaching experience; only 25% had more than one year’s experience as an adult literacy teacher. Of the 756 learners, 436 never had had any previous education (see 3.3 for more information).

Instruments used in the broad study included a teacher questionnaire and four reading and writing tasks for learners, all in Tetum. The written questionnaire for the teachers comprised 34 questions to elicit information on their educational and linguistic background, work experience, language use in the classroom and teaching circumstances like classroom conditions and availability of materials.

The reading and writing tasks for the learners focused on grapheme recognition, word reading, word writing and filling out a basic form on personal data like name and date of birth. The scores of the tasks were the number of graphemes identified correctly, the number of words decoded correctly within 3 min, the number of words correctly written after dictation and the number of correctly filled in blanks. The main focus in the comparisons of the different learners and groups was the influence of learner characteristics (like age or previous education), knowledge of the language of instruction (Tetum) and teaching characteristics (like the programme used, the number of contact hours or the experience of the teacher).

The in-depth study was carried out in 12 literacy groups in seven districts. Twenty lessons were observed and learners, teachers and (sub) district coordinators were interviewed. During the class observations, instructional practices and classroom interaction were audio recorded, field notes were taken and still photography was used to capture literacy events like texts written on the blackboard, and the layout of the class. An observation checklist was used to make sure all aspects of the classes visited would be described, such as teaching practices, languages used in classroom interaction, time allocated to different subjects, available resources and number of learners attending.

3.3 Results on Literacy Skills

In this section, we present the literacy skills the learners achieved and the impact of the programme (HBO/YEP and LHB) and familiarity with Tetum, the language of instruction.

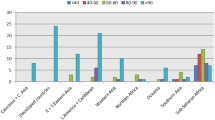

The 756 adult learners who participated in the reading and writing tasks of the broad study included people with prior primary education or adult literacy courses. In this section, we focus on the group of learners without any previous literacy education (N = 436), for whom the literacy programs Los Hau Bele and Hakat ba Oin/YEP were intended. These learners ranged in age from 15 to 76 years, with an average age of 41 years. Their length of attendance in the course ranged from less than 1 month to 15 months or from a few hours to more than 700 hours and averaged about 3.5 months. The proportion of non-Tetum speakers in this group was 25 per cent. The proportion of Tetum speakers did not differ significantly for the literacy programs attended (p = .28), but the groups did differ in learners’ average age, the average number of hours they had attended the course (p < .01) and the experience of the teachers (p < .05). In the statistical comparison we therefore control for these variables.

Table 1 presents the results of the reading and writing tasks of the group of 436 learners (428 without missing data), split up by literacy programme and proficiency in the language of instruction and literacy, Tetum.

Of the 30 graphemes in the grapheme task, the learners on average (see column ‘Total’) recognized 13 graphemes, ranging from 0 (14% of the learners) to all graphemes (2%). Of the 80 words in the word reading task, the learners on average read correctly about 11 words within 3 min, ranging from no words (59% of the learners) to all words (1%). On the basic form, learners on average filled in correctly around 3 items (mostly including their name and signature), ranging from 0 (17% of the learners) to the maximum of 10 (3%). The average number of words written correctly in the writing task for the whole group was around 3, ranging from no word written correctly at all (38% of the learners) to 10 (4%). The differences in the average scores of Tetum and non-Tetum speakers on beginning literacy skills were small. Proficiency in Tetum did not seem to provide an advantage at this basic literacy level of word reading and word writing.

To investigate the impact of learner and educational variables, a multivariate analysis of covariance in SPSS (Mancova) was conducted with grapheme recognition, word reading, form filling and word writing as dependent variables. Literacy program and Tetum proficiency were independent factors and learner’s age, number of hours they had been taught, and years of experience of the teacher were covariates. This analysis revealed a significant main effect of learners’ age on all literacy skills (p < .001), a significant main effect of number of hours learners had been taught for grapheme recognition and form filling (p < .05), but not for word reading (p = .82) and word writing (p = .20) and a trend for teacher experience on word reading, form filling and word writing (p < .10). Younger learners learned faster, the number of hours learners had received instruction mattered, and more experienced teachers were somewhat better than less experienced teachers at teaching their learners the alphabetic principle. Controlled for these variables, a significant main effect of program was found for all literacy skills (p < .01 for word reading and p < .001 for the other three skills); the main effect of speaking Tetum was not significant, except for grapheme knowledge (p < .01).

While the average scores on literacy skills were (very) low in general (on average 11 words read in 3 min), proficiency in Tetum turned out to be less important in building initial (word) reading and writing ability than expected. There was however a significant impact of programme, the eclectic analytic/synthetic Hakat ba Oin/YEP revealing significantly higher basic literacy skills than the letter/numeral based Cuban program Los Hau Bele.

Since all important learner-variables (that all mattered significantly) were controlled for, a closer look at the LHB program and the LHB classroom practices might shed more light on this.

4 The Cuban Literacy Programme

4.1 A Closer Look at Materials and Underlying Assumptions

The teacher manual of Los Hau Bele explains the content and use of the student manual in which connections between letters and numbers should facilitate learning because the learner ‘realises an association process between the known (the numbers) and the unknown (the letters)’. The numbers 1–5 are connected to the Tetum vowels, 6–20 to the consonants in the order that they are dealt with in the programme (see Fig. 1).

According to Gray’s classification, Los Hau Bele could be called mainly synthetic, although in the instructions on DVD and in the teacher manual it is recommended to start with larger meaningful units. It contains an additional ‘mnemonic aid’ in connecting letters to numbers. In terms of Chall’s (1999) two-stage model (from code to meaning), the Los Hau Bele method would be a three-stage method, or better; a two-stage method with a side-path (to numbers).

The teacher manual consists of a general introduction, an explanation on the use of the materials and the content of the 65 lessons, starting with the numbers 0–30 (phase 1), the consonants and the frequent letter-combinations (like bl, kr, pr or ai; phase 2), with the recommendation to combine each time letters with numbers and then with key words and a sentence, e.g., Sira han ha’as tasak (They eat ripe mangos) after which the key word (here: sira, they) is divided into syllables (si-ra), other possible syllables are practiced (sa, se, si, so, su, and as, es, is, os, us), and new words and sentences are added. The third phase is for consolidation, repetition, and some math operations like addition and subtraction. In lesson 65 the final test is taken.

The learner manual starts with four pages on which the 20 letters to be learned are presented: five letters per page, always in capital and lower case, each combined with a number, a key word and a drawing, some words divided in syllables and some used in phrases (see Fig. 2). Each of these pages is combined with a blank page to practise writing. The next page presents combinations of consonants (bl, pr, kr) with their syllables (bla, ble, bli, etc.), diphthongs (ai, au) or combinations of consonants and vowels (je, se, ze). After that, there are three blank pages to practise writing, one page with exercises for the numeracy operations, and one page with a statement in Tetum about being able to read and the importance of daily training. The last page presents the final test that learners have to do at the end of the programme, i.e., a form on which they can fill out their name, gender, country, a date, some phrases about themselves or their lives, and a signature.

The DVDs contain 65 video lessons. In most of the lessons a new letter or letter combination is introduced by a teacher, who explains the new lesson content and exercises to a group of adult learners. In each lesson the teacher follows more or less the same steps (slightly different from the recommendations in the teacher manual). Figure 3 presents a summary of the exercises in DVD-lesson 18.

Teachers were offered a one-day training session every 2 weeks during 3 months in which they learned about the didactic order in Los Hau Bele, the use of the DVDs and about a follow-up on the DVD lessons with their own explanations and exercises in their classes. Learners who passed the final test after 65 lessons received a certificate. The Ministry of Education aimed at having Los Hau Bele classes in each of the 442 villages in the country and kept track of the number of learners who (successfully) finished Los Hau Bele: from 25,000 by July 2009,Footnote 4 to 204,463 by January 2013.Footnote 5 As mentioned, part of the campaign strategy was to declare regions ‘free from illiteracy’ after all participants in that region had finished the three-month programme. And, although the reading and writing scores of most learners in this study were extremely low (see Table 1), by December 2012 all 13 districts had completed the programme and were declared ‘free from illiteracy.Footnote 6

4.2 Los Hau Bele Classroom Practices: Connecting Letters and Numbers

To find out how the teaching steps in Los Hau Bele classes are organised and how the connection of numbers to letters is embedded in the actual literacy teaching, one lesson of four teachers in different districts was observed. Focus was on the guidance of learners to acquire the alphabetic principle and whether and how the use of specific letter-number combinations contributed to that literacy acquisition process (see Boon, 2014 for further details). In the four lessons, the learners were seated on verandas on plastic chairs, their manuals, and notebooks on their laps. All four teachers used a blackboard in front of the group. In the lessons observed, none of them used the DVDs provided, due to either lack of electricity, gasoline for the generator or a vital cable. The teachers therefore taught using their own interpretation of what was supposed to be done, based on suggestions given in DVDs that they had watched earlier, the teacher manual and the training sessions attended.

The first teacher started the lesson with the letters R-r (the 17th lesson of the programme). On the blackboard she connected the R and r to the number 10, she repeated the five vowels connected to the numbers 1–5 and then explained the reading and writing of the syllables ra, re, ri, ro, ru, like in Fig. 4.

Learners were invited to the blackboard one by one, to each write and then read these syllables (ra, re, ri, ro, ru). Then the teacher wrote the key word for r, railakan (lightning) on the board, divided into syllables. She invited learners to add the numbers under each letter, like in Fig. 5, and then read the word, from letters to syllables (using the letter names eri-a-i rai, eli-a la, ka-a-eni kan) to the whole word (rai-la-kan, railakan).

After that, the learners practised writing their names, and if they were able to do so, wrote the corresponding number under each letter of their name (see Fig. 6).

The second teacher had started the (34th) lesson with writing a sample exercise on the blackboard as shown in Fig. 7. The letters p and r (referred to as pe and eri) were combined with the numbers 20 and 10, followed by a phrase containing the key word prepara (prepare), which was then divided into syllables. Next, all possible syllables with pr were practised: pra, pre, pri, pro, pru, and a few other words with pr and phrases containing words with pr were presented. Several times the learners repeated this complete text after the teacher and then they were asked to copy it in their notebooks. In the meantime, the teacher sat aside with an older learner with bad eyesight and helped him to memorize the 20 letter-number combinations of Los Hau Bele: A-1, B-14, D-15, etc.

The teacher then continued with two additional words with pr: presidente (president), preto (black, in Portuguese), and a phrase with a word with br: branco (white, in Portuguese). Next, the teacher invited learners to the blackboard to practise writing their names and the name of their village, subdistrict and district. He then sat aside again with the older learner to repeat the 20 letter-number combinations and practise the spelling of his name, and the other learners joined in repeating letters and numbers. The lesson ended with a repetition of the name of their village, subdistrict, and district.

The third teacher introduced the letter combination tr (the 42nd lesson), showed how to write both letters and how to form syllables, using the letter-names (te-eri-a tra, te-eri-e tre, etc.). She wrote the syllables tra, tre, tri, tro, tru on the blackboard and repeated their build up and pronunciation. The learners repeated the syllables several times after her and wrote them in their notebooks. The teacher also wrote a few words with tr, like: trata (treat/arrange), trigu (flour, wheat) and troka ((ex)change), which the learners copied in their notebooks as well. She then reminded the learners of the numbers 1–5 linked to each vowel, and they discussed which numbers had to be added under the consonants. Learners were invited to the blackboard and write the numbers under the letters of each syllable, as shown in Fig. 8. After this, learners wrote the syllables and numbers in their notebooks (see Fig. 9).

Next, the teacher explained about the build-up of the syllables by using her hand to cover letters (‘If you take out a from tra, what is left? If you take out tr from tru, what do you have left?’). Then they practised the series tra, tre, tri, tro, tru again by reading them out loud several times. The next part of the lesson was spent on practising writing names and other personal data (gender, country, birth date).

The fourth teacher was teaching lesson number 48 and spent the first hour on numeracy and the second on literacy. In the literacy part, the teacher connected the five vowels to the numbers 1–5, and then explained about all 20 letters and numbers in Los Hau Bele. The learners had to say each letter (using letter names like /ʒi’gɛ/ for g, /‘hɐgɐ/ for h) and corresponding number several times. Then the teacher explained that the complete Roman alphabet had six more letters, of which some are not used in Tetum but are frequently used in the other languages of Timor-Leste (like c and q in Portuguese and y in Indonesian). The 20 letters of Los Hau Bele and 26 of the Roman alphabet were read out loud several times by the learners. Next, the teacher listed syllables with consonant-vowel order, like ba, be, bi, bo, bu, and vowel-consonant order: ab, eb, ib, ob, ub, etc. (see Fig. 10).

The learners repeated syllables after the teacher, also in a top-to-bottom order (ba, ca, da; be, ce, de, etc.). After that, the teacher put words on the blackboard in which letters were missing. Of the missing letters, the numbers were given below a short horizontal line. Learners were invited to the blackboard to fill out the missing letter corresponding to that number to complete the words, like in Fig. 11, i.e., uma,Footnote 7 dalan, manu, maluk, kalsa, and kama (house, road, chicken, friend, trousers, and bed). Finally, the teacher showed how to read these words by blending letter names: ‘u emi a together uma’, ‘emi a eni u together manu’, etc.

Different from the series of steps as shown in the DVD’s, all four teachers did not start with meaningful units, but with letters first, and from there to syllables and only then words and phrases. Regarding the teaching of the alphabetic principle, it can be concluded that all four teachers paid attention to phonics, not by using the sounds but the letter names (which makes synthesis more difficult).

In all Los Hau Bele classes observed, a significant part of lesson time was spent on connections of numbers and letters and rote association of these combinations, e.g., a-1, b-14, d-15, etc. The classes included a lot of repetition and reading aloud to practise the pronunciation of the alphabet, the combinations of letters and numbers (learning them by heart, even writing the numbers under the letters of their own name), different combinations of letters to make syllables (e.g., ba-be-bi, pra-pre-pri) and whole words. Often numbers were written below the letters of those syllables and words.

5 Conclusion and Discussion

Research has shown that effective literacy education applies efficient methods aiming at an understanding of the alphabetic principle (Chall, 1999; Liberman & Liberman, 1990; Byrne, 1998) and builds reading and writing exercises around learner-relevant themes (Freire, 1970; Condelli & Wrigley, 2006). One can wonder whether the significant amount of lesson time spent on learning by heart associations of letters and numbers in the Cuban literacy programme Yo sí puedo/Los Hau Bele is time well spent in terms of reading and writing acquisition. Our study indicates it is not: it fails to help learners to build a deeper understanding of phoneme-grapheme correspondence and has no relation to literacy use in daily life. The teachers observed in this study in Timor-Leste tried to teach according to the letter-number principle often presented as the crucial element of this method, but they were clearly struggling to make it work for their learners. Learners were asked to write numbers under single letters and under (letters in) syllables, words or even phrases and names. Writing those numbers did not seem to help them grasp the alphabetic principle, needed for building initial reading and writing ability. On the contrary, they were put to an extra task which led to formula-like ‘magic’ on the blackboard and in their notebooks, irrelevant to any use of literacy in daily life. This distracted the learners’ attention from the important work of writing and sounding out letters and blending those to words. The class observations show that while the learners mainly were struggling with (writing or copying) association of letters and numbers, the teachers were doing the main part of the decoding work that the learners were supposed to do: analysing syllables and words, and blending sounds and syllables. Although the idea behind this method is that using familiar numbers would make the learning of the letters easier (Bancroft, 2008; Boughton, 2010; Relys Díaz, 2013), class observations revealed that this activity rather made things more complicated, because different from the systematic relationship between graphemes and sounds that facilitates learning the alphabetic principle (Byrne, 1998; Liberman & Liberman, 1990), there is no systematic relationship between letters and numbers, nor between numbers and sounds. The results in Sect. 3 illustrate these findings: while the average scores on literacy ability were (very) low in general (on average 11 words read in 3 min), the results showed an impact of programme: the letter/numeral based Cuban programme Los Hau Bele revealing significantly lower basic literacy skills than the eclectic analytic/synthetic Hakat ba Oin/YEP.

Class observations and survey results throw light on discrepancies between rhetoric and programme intentions on the one hand, and realities of achieved reading and writing ability on the other. As mentioned earlier, districts where all learners had attended a three month Los Hau Bele course, and passed the final test by writing their name and one short phrase about themselves, were declared ‘free from illiteracy’. Our findings show that that does not mean at all that the learners have become independent readers and writers (which probably no programme can achieve within 3 months). Boughton (2013:309) claims that in Timor-Leste ‘the adult literacy rate has nearly doubled’ as a result of this ‘popular-education-style national literacy campaign’ with use of the Cuban programme. In fact, little empirical research has been done on this, either in Timor-Leste or in other countries where other locally adapted versions of the Cuban method Yo, Sí Puedo! are being used comparable to Los Hau Bele. Lind (2008:91) refers to a case study in Mozambique that found ‘that the introduction of letters combined with numbers appeared to be too much at the same time and in too short a time for non-literate persons’. In Timor-Leste, Anis (2007:29) had noted that the letter-number combinations were found ‘confusing’. The findings from this study clearly point in the same direction and add the urgent question why this seemingly waste of time of learning the letter-number combinations has been and still is rather popular in many mass education programmes.

Counting the number of learners who obtained Los Hau Bele certificates cannot be translated into increased literacy rates and districts declared ‘free from illiteracy’. The fact that in districts declared ‘free from illiteracy’ no further literacy and post-literacy options were provided (because the resources were relocated to the districts not yet declared ‘free from illiteracy’), seemed to hamper people in taking more steps on the road of becoming ‘real’ readers and writers.

While lack of time, limited teacher experience and bad classroom conditions in Timor-Leste might explain the low results and slow progress in all programmes evaluated, the specific feature of the Cuban programme to take as a starting point connecting numbers with letters (that lacks any literacy learning related rationale) might explain why the learners in the Los Hau Bele programme did significantly worse in acquiring literacy. Since the Cuban programme is used in several developing countries, flagging the letter-number combinations as its ‘success factor’, and was praised with a Unesco award “for innovative teaching methods with successful outcome”, it is important to go beyond rhetoric and use empirical research to implement evidence-based literacy policies.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research, Science for Global Development (file number W 01.65.315.00).

- 3.

D. Boon, one of the authors of this paper, was involved in the development, piloting, and implementation of the Hakat ba Oin and Iha Dalan programmes when she was working as an advisor on adult literacy for UNDP Timor-Leste at Timor-Leste’s Ministry of Education from 11/2003 until 12/2008.

- 4.

This section is partly based on Boon 2014, chapter 5, p. 71–75.

- 5.

Presentation by Minister of Education J. Câncio Freitas on 06-07-2009 at the ‘Transforming Timor-Leste Conference’ in Dili.

- 6.

Information dd. 18-04-2013 from the Director of Recurrent Education, at the Ministry of Education.

- 7.

Information dd. 18-04-2013 from the Director of Recurrent Education, at the Ministry of Education.

- 8.

This section contains data as presented in Boon 2014, chapter 6, p. 154–159.

- 9.

The teacher later changed the 1 (that can be seen in the picture before the letters ma) into a 5, when he realized that he had made a mistake.

References

Anis, K. (2007). Assessment of the effectiveness of literacy and numeracy programs in Timor-Leste; Timor-Leste Small Grants program. USAID. Retrieved: http://www.literacyhub.org/documents/assessment_timor-leste.pdf

Bancroft, P. E. (2008). Yo, sí puedo: A Cuban quest to eradicate global illiteracy. Master thesis, University of California.

Blommaert, J. (2013). Ethnography, superdiversity and linguistic landscapes. Chronicles of complexity. Multilingual Matters.

Boon, D. (2011). Adult literacy teaching and learning in multilingual Timor-Leste. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 41(2), 261–276.

Boon, D. (2014). Adult literacy education in a multilingual context; teaching, learning and using written language in Timor-Leste. PhD-thesis, Tilburg University.

Boon, D., & Kurvers, J. (2012). Ways of teaching reading and writing: Instructional practices in adult literacy classes in East Timor. In P. Vinogradov & M. Bigelow (Eds.), Low educated second language and literacy acquisition, 7th symposium, September 2011 (pp. 67–91). University of Minnesota.

Boughton, B. (2010). Back to the future? Timor-Leste, Cuba and the return of the mass literacy campaign. Literacy & Numeracy Studies, 18(2), 58–74.

Boughton, B. (2012). Adult and popular education in Timor-Leste. In M. Leach, N. Canas Mendes, A. B. da Silva, B. Boughton, & A. da Costa Ximenes (Eds.), New research on Timor-Leste (pp. 315–319). Timor-Leste Studies Association.

Boughton, B. (2013). Timor-Leste: Education, decolonization and development. In L. Pe Symaco (Ed.), Education in South-East Asia (pp. 299–321). Bloomsbury Academic.

Byrne, B. (1998). The foundation of literacy: The child’s acquisition of the alphabetic principle. Psychology Press.

Cabral, E. (2013). The development of language policy in a global age: The case of East-Timor. In J. Arthur Shoba & F. Chimbutane (Eds.), Bilingual education and language policy in the global south (pp. 83–103). Routledge.

Cabral, E., & Martin-Jones, M. (2012). Discourses about adult literacy and about liberation interwoven: Recollections of the adult literacy campaign initiated in 1974/5. In M. Leach, N. Canas Medes, A. B. da Silva, B. Boughton, & A. da Costa Ximenes (Eds.), New research on Timor-Leste (pp. 342–348). Timor-Leste Studies Association.

Chall, J. S. (1999). Models of reading. In D. Wagner, R. Venezky, & B. Street (Eds.), Literacy: An international handbook (pp. 163–166). Westview Press.

CIA, The World Factbook. (2019). https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/tt.html. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

Condelli, L., & Wrigley, H. (2006). Instruction, language and literacy: What works study for adult ESL literacy students. In I. van de Craats, J. Kurvers, & M. Young-Scholten (Eds.), Low-educated adult second language and literacy acquisition. Proceedings of the inaugural symposium, Tilburg 2005 (pp. 111–133). LOT, Netherlands Graduate School of Linguistics.

Da Conceição Savio, E., Kurvers, J., Van Engelenhoven, A., & Kroon, S. (2012). Fataluku language and literacy uses and attitudes in Timor-Leste. In M. Leach, N. Canas Mendes, A. B. da Silva, B. Boughton, & A. da Costa Ximenes (Eds.), New research on Timor-Leste (pp. 355–361). Timor-Leste Studies Association.

De Araujo e Corte-Real, B., & Kroon, S. (2012). Becoming a nation of readers in Timor-Leste. In M. Leach, N. Canas Mendes, A. B. da Silva, B. Boughton, & A. da Costa Ximenes (Eds.), New research on Timor-Leste (pp. 336–341). Timor-Leste Studies Association.

Ethnologue. https://www.ethnologue.com/country/TL. Retrieved July, 9, 2019.

Filho, A. Q. M. (2011). O uso do método de alfabetização “Sim, eu posso” pelo MST no Ceará: o papel do monitor da turma. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade Federal de São João Del-Rei.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder.

Goodman, K. S. (1986). What’s whole in whole language? A parent-teacher guide to children’s learning. Heinemann.

Gray, W.S. (1969). The teaching of reading and writing: An international survey, 2. Scott, Foresman and Co. / UNESCO.

Kurvers, J. (2002). Met ongeletterde ogen: Kennis van taal en schrift van analfabeten. Aksant.

Kurvers, J. (2007). Development of word recognition skills of adult L2 beginning readers. In N. Faux (Ed.), Low educated second language and literacy acquisition: Research, policy and practice. Proceedings of the second annual forum (pp. 23–43). The Literacy Institute, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Kurvers, J., & Stockmann, W. (2009). Wat werkt in alfabetisering NT2? Een vooronderzoek naar succesfactoren alfabetisering NT2. Tilburg University.

Liberman, I., & Liberman, A. (1990). Whole language vs. code emphasis: Underlying assumptions and their implications for reading instruction. Annals of Dyslexia, 40, 51–76.

Lind, A. (2008). Literacy for all: Making a difference. Fundamentals of educational planning, 89. UNESCO.

Ministry of Education. (2011a). National education strategic plan 2011–2030, August 2011. . Retrieved: http://www.globalpartnership.org

Ministry of Education. (2011b). Mother tongue-based multilingual education for Timor-Leste: National policy. Komisaun Nasional Edukasaun.

Morais, J., & Kolinsky, R. (1995). The consequences of phonemic awareness. In B. De Gelder & J. Morais (Eds.), Speech and reading. A comparative approach (pp. 317–338). Erlbaum (UK) Taylor & Francis.

Purcell-Gates, V. (1999). Family literacy. In M. Kamil, P. Mosenthal, P. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. III, pp. 853–870). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Quinn, M. (2013). Talking to learn in Timorese classrooms. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 26(2), 179–196.

RDTL (República Democrática de Timor-Leste). (2002). Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste. RDTL.

Relys Díaz, L. I. (2013). De America soy hijo…: Crónica de una década de alfabetización audiovisual. La Guerilla Comunicacional.

UNDP. 2018. Human Development Index 2018. Statistical annex, Table 9.

Van de Craats, I., Kurvers, J., & Young-Scholten, M. (2006). Research on low-educated second language and literacy acquisition. In I. Van de Craats & J. Kurvers (Eds.), Low-educated second language and literacy acquisition: Proceedings of the inaugural symposium, Tilburg 2005 (pp. 7–23). LOT, Netherlands Graduate School of Linguistics.

Wagner, D. A. (2004). Literacy in time and space: Issues, concepts and definitions. In T. Nunes & P. Bryant (Eds.), Handbook of children’s literacy (pp. 499–510). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Boon, D., Kurvers, J. (2021). The Cuban Literacy Programme in Timor-Leste; ‘Magic’ on the Blackboard. In: Spotti, M., Swanenberg, J., Blommaert, J. (eds) Language Policies and the Politics of Language Practices. Language Policy, vol 28. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-88723-0_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-88723-0_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-88722-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-88723-0

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)