Abstract

The aim of this chapter is to investigate whether risk and risk management disclosure of Italian listed banks increased after the introduction of the single supervisory mechanism (SSM) in November 2014, as well as whether those banks that underwent European Central Bank (ECB) on-site/off-site inspections implemented more risk-based disclosure items than non-supervised banks did in the period of 2014–2016. To reach this aim, a random-effects generalized least square regression model and a fixed-effects regression model are performed. The findings show that, after the introduction of the SSM, there was an overall implementation of risk and risk management disclosure for all Italian listed banks. In addition, the empirical results confirm that those banks that underwent ECB on-site/off-site inspections perceived being under greater pressure to become more aware and structured in their risk management communication. Our findings may be of interest to regulators and accounting standard setters because they provide insights into potential tools that could be used to further enhance risk management systems and improve the corresponding disclosure.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Single supervisory mechanism

- Risk disclosure

- Risk management

- European Central Bank

- Enterprise risk management (ERM)

1 Introduction

The external environment in which European Union (EU) banks operated in the last decade has been so unpredictable as to spread a common belief that banking risk and risk management information is not sufficiently disclosed (Linsley and Shrives 2005a). The notion of risk is related to the uncertainty that something could happen in the future and involve some kind of loss or damage arising as a result of that event (Kaplan and Garrick 1981).Footnote 1 The longstanding issue of enhancing bank transparency led the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS 1998) to act to encourage banks to be more aware of their risk exposure and responsible for reporting it properly to stakeholders. Following this, the marketplace became more sensitive to the risk-based disclosure provided by all banks, orienting the investment decision-making process towards more transparent financial institutions. The guidelines for a greater risk disclosure were then strengthened through the issuance of Basel II’s Pillar 3 in 2004, which obligated all banks to develop more structured and extensive risk disclosure about credit, market, operational, and interest rate risks (BCBS 2004).Footnote 2 Notwithstanding, the discretionary room left to bank managers in defining the quantity and quality of risk disclosure was wide enough to suggest stricter control by supervisory banking authorities for assuring appropriate banking risk disclosures.Footnote 3

Since November 2014, the supervisory control exerted by the European Central Bank (ECB) over European banks has been extensive and formidable, primarily because of the implementation of the single supervisory mechanism (SSM) regulation. This regulation submits ‘significant’Footnote 4 banks in the EU to on-site/off-site inspections concerning not only specific accounting items (i.e. non-performing loans) and accountability policies (i.e. provisioning) but also risk management systems and disclosure (Darvas et al. 2013; Masciandaro 2015; Mesnard et al. 2016). An essential part of the oversight activity of ECB under the SSM is the assessment and control of the risk exposure and risk management strategy of EU banks through horizontal and continuous analyses (ECB 2018).Footnote 5 The subjects of direct evaluation in terms of risk assessment include not only accounting data but also risk-based disclosures, as such information contributes to defining the bank’s risk profile. In addition, the ECB required an updated depiction of the risk exposure and risk management systems of such banks on a more regular, even daily, basis by performing an ad hoc risk-based functional investigation (Masciandaro 2015), consequently assessing the development of corporate risk governance and culture. Hence, such quantitative and qualitative analyses, aiming at quickly pinpoint critical situations that can threaten the going concern of a single bank, and in particular cases, the stability of the entire banking sector (ECB 2018), gave the ECB sufficient information to map the state of the art of the risk profiles of all EU banks in that year.

Before the introduction of the SSM, the supervisory activities over the EU banks were all executed by the national central banks, although the depth and the accuracy of controls cannot be compared to what was accomplished by the SSM bodies over the significant banks. The supervisory pressure created by the SSM increased the EU banks’ perception of being controlled about the accuracy of their accounting practices and the adequacy of their risk management systems to a degree far beyond what national central banks did years before (Alexander 2014).

Since banking corporate reporting outcomes and transparency are influenced by the supervisory authorities’ policies (Bischof et al. 2015), it is possible that banks that have undergone ECB on-site/off-site inspections could be encouraged to develop more organised and integrated risk management systems and disclosures. The reasons for such a behaviour could be related to the need to comply with more stringent rules on risk and risk management disclosure or the interest in seeking legitimacy in the banking context in which they operate (Di Maggio and Powell 1983). Indeed, after the implementation of the SSM, market participants and stakeholders became more demanding about banking risk profile disclosure. Since the informative weakness of risk exposure was interpreted as a sign of potentially critical situations where managers felt the need to hide or omit relevant information in order to avoid proprietary costs, banks could implement risk disclosure to opportunistically increase transparency and protect their reputation and market performance.

Recently, debates about the effects of supervisory and control pressures on accountability practices (Barth et al. 2004; Boudriga et al. 2009), financial stability (Barth et al. 2006; Kaufmann et al. 2008; Quintyn and Taylor 2002) and bank performance (Barth et al. 2002; Gauci and Grima 2020) have intensified, but there is still a lack of knowledge about whether and how such pressures could affect risk management disclosures in the banking context. In addition, practitioners have suggested implementing risk-based disclosures to meet the upward demands for greater risk transparency and comparability (PricewaterhouseCoopers 2008).

The risk literature provides empirical evidence on the main determinants that influence both risk and risk management disclosure. On the one hand, some studies have focussed on firm-specific factors, such as the size, board composition, leverage, riskiness, profitability and capital adequacy of banks (Bischof 2009; Linsley et al. 2006; Mukhiba et al. 2020; Oliveira et al. 2011a, b; Woods et al. 2009; Yong et al. 2005). On the other hand, some scholars have investigated the role of institutional and contextual factors, such as regulations, legal protections and the financial system on risk accounting disclosure (Barakat and Hussainey 2013; Beltratti and Stulz 2012). Within the latest research stream, there is little evidence about whether and how supervisory pressure could exert a direct effect on risk management disclosures in the banking sector. Hence, this chapter seeks to address this crucial research gap.

Our work has two objectives. First, our analysis is aimed at determining whether Italian banks increased both risk and risk management disclosures under the endorsement of the SSM regulation. Second, we intend to examine whether, under SSM regulation, the supervisory and control pressure exerted by the ECB through stress tests and asset quality reviews encouraged Italian listed banks exposed to such direct inspections to develop and disclose more integrated risk. Hence, this chapter poses two research questions:

RQ1: Did the Italian listed banks increase risk-related disclosure in their annual reports after the establishment of the SSM in 2014?

RQ2: Did the Italian listed banks that underwent ECB supervision increase risk-related disclosure in their annual reports to a greater extent compared with other Italian banks that did not undergo such supervision?

As the ECB commenced its supervisory activity on EU credit institutions in November 2014, this study chooses the periods of 2011–2013 and 2014–2016—before and during on-site/off-site inspections, respectively—to assess (and control) the net effect of supervisory pressure by the SSM on the implementation of risk management disclosure in an Italian banking context. The choice of investigating the Italian banking context reflects the need to shed light on a sector hit in the last 10 years by many issues and criticalities, resulting in profound changes (KPMG 2019). The weak trade of financial instruments, the reduction of interest rates, the contraction of interest margins, the deep deterioration of credit quality, partly due to the effects of the global financial crisis, the increasing oversight pressure of international banking authorities and deep changes in banking regulatory frameworks (e.g. the introduction of the SSM, the issuance of Basel III’s new rules of higher minimum levels of regulatory capital and the adoption of strategic policies of non-performing loans management) contributed to creating a unique historical banking setting in Italy between 2009 and 2017, thus claiming for additional research attention.

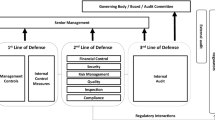

To investigate whether the introduction of the SSM increased risk-related disclosure in the annual reports of all Italian listed banks and whether those banks subjected to on-site/off-site inspections by the ECB likewise provided more disclosure than those banks not subjected to such inspections, this study runs a random-effects generalized least square (GLS) regression and a fixed-effects regression. The measure of risk and risk management disclosure corresponds to a modified version of the enterprise risk management (ERM) index originally developed by Desender and Lafuente (2009), and it is obtained through a content analysis performed on risk-based information within the annual reports of banks. The number of disclosed risk items is counted and scaled with the maximum possible number of risk items suggested by the 2004 ERM model developed by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO 2004).Footnote 6 In addition, to corroborate the statistical results of the above-mentioned models, we monitor the change in the yearly mean ERMit index over the 2011–2016 period and compare the 3-year mean ERMit index of supervised banks to that of non-supervised banks during the 2014–2016 period.

This chapter shows that, after the introduction of the SSM, there has been an overall increase of risk and risk management disclosure for all Italian listed banks. Hence, the evidence suggests that, under the ECB intervention aimed at strengthening supervisory pressure on banks beginning in November 2014, the implementation of risk-based disclosure by Italian listed banks has become quantitatively more pronounced. Moreover, the empirical results confirm that those banks that underwent ECB on-site/off-site inspections disclosed a higher number of risk items than did non-supervised banks in the same period. As a consequence, although risk management systems generally became more formalised and better disclosed to the market in the 2011–2013 and 2014–2016 periods, those Italian listed banks that did not receive any supervisory control did not demonstrate the same massive improvement in risk management systems exhibited by supervised banks. This trade-off highlights how the pressure perceived by Italian banks under ECB supervision acts as an incentive towards becoming more aware of their structured risk management approach and communication.

Hereafter, this chapter shows how the regulatory context and supervisory pressure may act as crucial drivers for the understanding of differences of behaviour of banks listed in the same (Italian) market but operating in different settings (under or without direct supervisory). Yet, in accordance with our findings, after the implementation of the SSM regulation, the financial market has benefitted from an improvement of the risk disclosure.

The relevance of this chapter is twofold. First, it provides a clear and ongoing picture of the level of risk disclosure in the Italian banking setting. Second, it has important policy implications for regulators, banks and practitioners. Our findings suggest that, because of the enforcement of supervisory pressure, banks have improved their quantitative risk and risk management disclosures. This study can provide insights to regulatory and supervisory authorities on how to develop ad hoc interventions to increase the efficiency and resilience of the banking system. However, to the best of our knowledge, it remains unclear whether better risk information is directly associated with the role of the ECB as a single supervisor, or because of the stricter tasks, banks have improved their risk management practices by increasing the quality of their reporting.

The remainder of the chapter is structured as follows: Sect. 2 presents the literature review and specifies the research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the sample selection procedure and the research method. Section 4 shows the results and the robustness tests. Section 5 provides the discussion of outcomes and the conclusions.

2 Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1 Single Supervisory Mechanism and Risk Disclosure by Banks

Risk disclosure has strategic importance for the efficiency of financial markets and for overall financial stability, playing a pivotal role in strengthening market discipline and building trust in stakeholder relationships (Scannella 2018). As the communication of risks is almost entirely qualitative in nature, it sometimes suffers from a lack of specificity (Amran et al. 2009; Lajili and Zéghal 2005); moreover, risk disclosure is intrinsically subjected to discretional choices by managers, which can undeniably affect its qualitative and quantitative dimensions (Bischof et al. 2015; Maffei et al. 2014). The risk information that is ultimately disclosed is partly subjective and non-verifiable, which inherently permits discretion (Dobler 2008). In addition, proprietary cost theory suggests that managers may be reluctant to provide sensitive information that can be strategically exploited by competitors to cause serious damage in terms of competitive advantage (Leopizzi et al. 2019; Verrecchia 1983).Footnote 7 By adopting the theory of proprietary costs for explaining the hidden policy of risk-based disclosure, the more favourable risk-based news is, the greater advantages for the company and the higher the incentive to disclose risk-based information becomes. Conversely, the larger the proprietary costs related to risk management information are, the lower the propensity to disclose risk-based information becomes (Verrecchia 1983). Consequently, bank managers may be encouraged to adopt more secretive behaviours by, for example, reducing the transparency of their risk reporting, in accordance with proprietary cost theory.

According to the institutional theory of Di Maggio and Powell (1983), like any other organisations, firms seek legitimacy inside the social context where they reside. The pressure that the institutional context exercises over the organisational structures and behaviour of companies, which is particularly strong in the Italian banking sector, induces firms to satisfy the need for institutionalisation by undergoing coercive isomorphism (Di Maggio and Powell 1983; Hawley 1968; Scott 1994). In other words, the banks adopt homogeneous behaviours in terms of risk management and risk-based disclosure as a consequence of the strong formal and informal pressure on international banking authorities through regulations, control mechanisms and convictions in terms of complying with specific risk management and disclosure guidelines. Indeed, the factors that could potentially influence risk disclosure have always attracted considerable attention (Rajab and Handley-Schachler 2009), especially among academics, standard setters and regulators (Basel II; Basel III; IFRS 7).

Many studies have identified heterogeneous determinants of risk reporting strategies in the banking context, such as bank size, board composition, leverage, profitability and capital adequacy (Bischof 2009; Linsley et al. 2006; Mukhiba et al. 2020; Oliveira et al. 2011a, b; Woods et al. 2009; Yong et al. 2005). Similarly, the level of legal protection and the efficacy of the financial system have been demonstrated to influence risk reporting outcomes (Barakat and Hussainey 2013; Beltratti and Stulz 2012). The marked interest in investigating the banking context is attributable to its relevance for financial systems and to its exposure to strong control pressure from supervisory authorities concerning the reliability and transparency of banks with respect to their accounting practices, as well as the accuracy of their risk disclosures (Ghezzi and Magnani 1998).

Despite the enforcement of SSM regulation and its consequences for the risk profiles of banks, the extant research has yet to consider whether this regulation and the supervisory practices it entails have had a measurable influence on risk disclosure. Thus, this study seeks to meaningfully address this limitation in the literature, taking as a point of departure the arguments that the nature and intensity of the associations remain unclear, the minimum compulsory requirements have not yet been fulfilled and the effectiveness of market discipline has consequently been affected (Oliveira et al. 2011a, b).

Despite the limited focus of the extant risk literature on whether developments in the regulatory setting affect risk disclosure, several previous studies have demonstrated that compliance with Basel II requirements positively affects risk disclosure by banks (Bischof et al. 2015; Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2008; Linsley and Shrives 2005b; Oliveira et al. 2011a, b). Likewise, the introduction of the Basel III regulatory framework has had a direct impact on the quality of such risk disclosures.

The 2007–2008 global financial crisis exposed the foundational unsuitability and weakness of risk management and monitoring systems in the EU banking context (e.g. Gualandri 2011). In response, the Basel III regulations forced banks to adopt and implement more accurate methods of risk measurement and to pursue more holistic approaches to risk management systems, orienting banks towards more prudent lending practices and business strategies. Pillar 1 of the Basel III framework mandated more standardised methods for calculating bank risks (i.e. credit risk, market risk, credit valuation adjustment risk and operational risk) to avoid discretional and opportunistic risk assessment procedures. Pillar 2 imposed new supervisory and control practices over banks to regulate their risk exposure (BCBS 2019; Moody’s Analytics 2011). In line with the increased interest by the Basel Committee in the risk management systems of banks and related reporting procedures, Elamer et al. (2019) developed a risk disclosure index (RDI) to measure the overall level of risk disclosure of 100 banks listed on 14 Middle Eastern and North African stock exchanges. Via this RDI, Elamer and colleagues found that overall risk disclosure increased after the Basel III agreement. Likewise, Polizzi and Scannella (2020) empirically determined, albeit with a limited number of items, that risk disclosure by the ten largest Italian banks in terms of total assets improved during the 2012–2015 period after Basel III. Whereas Elamer et al.’s (2019) investigation demonstrated a continuous increase in risk disclosure from 2006 to 2013, Polizzi et al. (2020) empirically showed an increasing trend among the ten largest Italian banks in terms of total assets during the 2012–2015 period following the 2010 Basel III agreement.

Similar to the Basel accords, the introduction of the SSM was a significant supervisory and regulatory development in the EU—one that imposed much stricter supervision requirements on banks, including even more banking regulations. Under these new regulations, all EU banks must undertake the internal capital adequacy assessment process (ICAAP) to identify and evaluate all heterogeneous risks to which they are exposed completely and accurately. Yet, the ICAAP represents one of several planned interventions within the broad and systematised EU banking supervisory agenda. The current activities of supervisory authorities include investigating whether banks put in place a comprehensive risk management process to identify, monitor, control and mitigate all material risks, thereby assessing their overall capital adequacy in relation to their established risk profile (Gualandri 2011). The control activities of supervisory authorities often generate substantial dialogue between supervisors and supervised banks such that when the former identifies excessive risks, insufficient capital and/or deficiencies, the latter must promptly intervene to decisively reduce these risks, address these deficiencies and/or restore capital (BCBS 2019). Such supervisory control over the adequacy and prudence of risk management strategies and approaches could impose on banks the pressure needed for them to acknowledge their risk management practices more fully and more accurately in their risk disclosures.

The endorsement of SSM regulation in the EU banking context has generated increased interest in researching its potential effects on the behaviours of banks. Although some studies have demonstrated that, after the introduction of the SSM, a general increase in credit default swaps (Pancotto et al. 2020) and a general reduction in lending activities by significant banks have occurred, Fiordelisi et al. (2017), for instance, warned that there is still a lack of debate about the association between the endorsement of the SSM and the number of risk disclosure items in the banking context. Hence, the present study seeks to address this gap by investigating whether the number of risk and risk management disclosure items of all Italian listed banks increased after the introduction of the SSM in November 2014.

The SSM regulation has imposed stricter supervisory practices over banks with the primary aim of rebuilding trust in the European banking sector and increasing the resilience of banks. Because of such enhanced supervisory pressure, European banks may be more encouraged to increase the quality and depth of their risk disclosures.

The more intensive regulatory scrutiny of the risk profiles of banks and risk disclosure suggests that we address the following hypothesis:

H1: Italian listed banks increased the number of risk items disclosed in their annual reports after the establishment of the SSM in 2014.

2.2 Strong Supervisory Pressure and Risk Disclosure by Banks

Since November 2014, the ECB has exercised widespread and formidable direct supervisory authority over significant banks. Under SSM regulation, the ECB has multiple pathways to enforce this authority, such as by conducting supervisory reviews and on-site inspections and investigations. As a consequence, directly supervised banks are subject to significantly greater supervisory pressure than other banks (i.e. less significant ones) are within the scope of the SSM regulation.

Several studies have examined the effect of supervisory pressure on the behaviours of banks. Barth et al. (2013), for instance, found that supervisory power is positively associated with bank operating efficiency in countries with independent supervisory authorities. Delis and Staikouras (2011) observed that effective supervision reduces bank fragility, whereas Hirtle et al. (2020) showed that supervision is negatively associated with risky loan portfolios. Focussing specifically on bank accounting, Barth et al. (2002) claimed that when central banks supervise non-central banks, the latter tend to have more non-performing loans.

Despite ongoing debate on the possible ‘outcomes’ of bank supervision, the previous literature has provided little empirical evidence on the potential effect of major supervisory pressure on the reported risk disclosures of banks (Barakat and Hussainey 2013; Bischof et al. 2015; Elamer et al. 2019; Neifar et al. 2020). Investigating the quality of operational risk disclosure, Barakat and Hussainey (2013) observed that powerful and independent bank supervisors encourage bank executives to report voluntary the operational risk disclosure (ORD). The authors suggested that strict supervision of the banking sector could shape the discretionary decisions of bank management, persuading them to report more risk information. Likewise, Elamer et al. (2019) found that the quality of the Sharia supervisory board, which is responsible for assessing whether Islamic bank transactions meet the requirements of Islamic law and values, is positively associated with the extent of ORD reported by Islamic banks. Further, Bischof et al. (2015) observed that, although banks are subject to the same requirements by regulators and standard setters, only those institutions from countries in which the banking regulator has more supervisory powers and resources report a higher level of risk disclosure. In accordance with these findings, Oliveira et al. (2011b) suggested that banking supervision contributes to limiting excessive risk taking by imposing socially desirable levels of mandatory risk information as a necessary element of the government’s prudential supervision of banks.

Similar to findings from the previous literature, we expect that the supervisory pressure exercised directly by the ECB on significant banks could affect the extent of their risk disclosure. The ECB is a more powerful authority compared with previous supervisory institutions (i.e. national central banks). As a consequence of its mandate and expertise in financial stability issues, the ECB has the power to deploy macroprudential tools, such as capital buffers, with regards to all EU banks, even against the objections of national competent authorities (Tröger 2014). The ECB also has an ‘exclusive competence’ concerning supervisory tasks, such as overseeing robust and sound internal governance; assessing risk management arrangements, strategies, processes and mechanisms; and conducting consolidated supervision (Ferran and Babis 2013).

By considering the specific activities that the ECB employs during its direct supervision of significant banks, it is reasonable to argue that these credit institutions are encouraged to increase risk and risk disclosure for several reasons. First, the ECB has only performed strict ‘risk-focussed’ control (i.e. ICAAP) over EU ‘significant’ banks (128 banks overall), and it has thus expressed judgements on key risk factors and analysed banking risk profiles in only the first year of the SSM regulation (2014). Second, the ECB exercises daily supervision based on the assessment of bank risks through an integrated system of analysis and quantification of risks, i.e. the risk assessment system, by which central banks develop the supervisory review and evaluation process. This process is aimed at evaluating and reviewing the banks’ risk exposure and the risks resulting from stress tests (Masciandaro 2015). In particular, the ECB has developed a comprehensive approach to assessing governance and culture, leveraging a variety of supervisory tools—for instance, the assessment of meetings with key function holders and the review of documentation such as governance manuals, codes of conduct, risk and remuneration policies, and management body documents and minutiae (Walter and Narring 2020). Hence, the ECB is responsible for conducting risk-focussed supervisory activities to an extent never implemented before in the European banking context, and as such, these activities present a unique opportunity to determine whether this supervisory pressure on banks is associated with changes in risk disclosure. More specifically, we are interested in researching whether the quantity of risk disclosure increases immediately after the start of direct inspections by the ECB. Starting from these considerations, we develop our second hypothesis:

H2: The Italian listed banks that underwent ECB on-site/off-site supervision increased the number of risk items disclosed in their annual reports to a greater extent compared with other Italian banks that did not undergo such supervision.

3 Method

3.1 Sample Selection

Our sample is composed of active Italian listed banks involved in traditional lending activities from 2011 to 2016, as extracted from Bankscope Bureau van Dijk. The choice of this investigation period is made due to the necessity of symmetrically capturing what happened 3 years before and 3 years after the introduction of the SSM (in November 2014). The final number of extracted Italian listed banks is 31, comprising 8 supervised banks and 23 non-supervised banks.Footnote 8

3.2 Research Model

For this investigation, a random-effects GLS regression and a fixed-effects regression are runFootnote 9:

ERM, the dependent variable, corresponds to the ERM index and measures the number of risk and risk management disclosure items of each bank i for each year t. To measure the level of risk and risk management disclosure, a content analysis is performed on risk-based information within the banks’ annual reports, using the shared and across-the-board features of ERM models implemented by the COSO in 2004 (COSO 2004) as a judgement parameter and yardstick. Although COSO has implemented many other ERM models to accommodate upcoming risk management needs, such as Enterprise risk management—Aligning risk with strategy and performance (2016), Enterprise risk management—Integrating with strategy and performance (2017) and Enterprise risk management—Applying enterprise risk management to environmental, social and governance-related risks (2018), we conduct our analysis by adopting the ERM 2004 model, since the investigated periods (2011–2013; 2014–2016) were immediately prior to the introduction of such ERM frameworks. Moreover, during 2016, the Italian listed banks still defined their ERM systems and disclosures according to the guidelines of the ERM 2004 framework, considering that the COSO issued Enterprise risk management—Aligning risk with strategy and performance in the middle of the year and the banks needed an adaptation period to voluntarily acknowledge/adopt such a revolutionary risk management model. Although the adoption of an ERM system was warmly encouraged by COSO and other international banking authorities, its implementation has never been mandatory.

For all the reasons outlined above, this study uses a modified version of the ERM index developed by Desender and Lafuente (2009) as the proxy for detecting risk-based disclosure, thereby acknowledging crucial aspects of the theoretical and methodological framework of the COSO (2004). The content analysis is conducted by looking for 103 items of the 254 suggested by the COSO (2004) ERM framework. The strategy adopted for building the risk and risk management index (ERM) looks for any kind of disclosure in the banks’ annual reports about each of the 103 risk items suggested by the COSO (2004) framework. The aim is to identify whether the banks conveyed risk-based information, without considering how many words are used for such a purpose. Hence, the content analysis captures only the number of risk and risk management items; thus, the risk disclosure is analysed from a quantitative (and not qualitative) perspective. The 103 items are selected according to their perceived ability to capture the most relevant issues for companies during the investigated period. Among these 103 items are some risk management and control models, which, although not explicitly indicated by COSO (2004) as essential elements in the ERM model, have been later formalised within subsequent ERM frameworks in 2016, 2017 and 2018. The items used to construct ERM are essentially attributable to the eight layers composing the three-dimensional cube and representing the phases of the risk management system of the COSO (2004), such as internal environment, objective setting, event identification, risk assessment, risk response, control activities, information and communication and monitoring. Unlike the proxies used by Desender and Lafuente (2009) and Desender (2010), the ERM index adopted here is a measure of risk management disclosure and is calculated as follows:

The variable ERM reflects the risk-based information disclosed in year t by bank i about its risks and risk management system, where nit represents the maximum number of items for company i in year t (i.e. 103).Footnote 10 Below, xit is equal to 1 if one of the ERM items is disclosed inside the annual report, and 0 otherwise. The higher the ERM index, the higher the number of items related to risk and risk management disclosed in the annual report. By searching for 103 items describing the risk management system in the annual reports of 31 Italian listed banks for 6 years, the analysis yields 19,158 year-end, hand-collected, risk-based data items.

SSM is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the period under investigation followed the introduction of the SSM (i.e. years 2014, 2015 and 2016) and 0 otherwise. By selecting 3 years immediately before and after the introduction of the SSM, we are able to directly observe the correlation between supervisory pressure and the implementation of risk and risk management disclosure. We expect a positive coefficient for the SSM proxy, which would support the thesis that, the number of risk and risk management disclosure items has been increasing after the introduction of the SSM.

SUPERV is a dummy variable equal to 1 if the bank underwent ECB on-site/off-site inspections during the 2014–2016 period and 0 otherwise. As the ECB commenced supervisory activities over EU credit institutions in November 2014, this study chooses 2011–2013 as the period before the commencement of on-site/off-site inspections and 2014–2016 as the period during on-site/off-site inspections. To support the thesis that those banks that have been subjected to stringent controls by the ECB through inspections have implemented a number of risk items due to such pressure, we expect a positive coefficient for the SUPERV proxy.

In the above-mentioned model, we control for some bank-level characteristics that may affect banks’ behaviour, influence practices of risk management and affect risk disclosure. First, we control for bank growth through the market-to-book ratio (i.e. MTB; Chen and Zhao 2006). Previous studies show that banks with a high market-to-book ratio are more likely to implement ERM programmes and enhance risk-related disclosure to preserve the franchise value (Berry-Stolzle and Jianren 2018). According to agency theory, and consistent with Buckby et al. (2015), a bigger market-to-book ratio indicates greater expectations about future cash flows. Since future cash flows are inherently uncertain, firms with high market-to-book ratios tend to have more volatile share prices than firms with small market-to-book ratios do. Thus, companies with larger market-to-book ratios are expected to disclose greater amounts of information (Panfilo 2019).

We control the current state of banking liquidity with LOAN, the ratio of net loans of the year scaled by total assets of the year. For most banks, loans are the largest and most obvious source of risk, including credit risk and counterparty risk. Banks with higher loans are more likely to disclose about risks, particularly credit and counterparty risks (BCBS 2000).

Because LLP (i.e. the ratio of specific loan loss provisions of the year scaled by the net profits of the year) and the impaired loans ratio (IMPL) reflect the quality of the banking credit portfolio and lending activities, they can capture the distortive effects generated by the risk exposure on the risk management behaviour and disclosure (Beaver et al. 1989; Beatty and Liao 2014; Meeker and Gray 1987). In fact, banks with higher levels of LLP and IMPL are riskier, and according to proprietary theory, more reluctant to disclose sensitive information, with negative effects on the quality of risk disclosure (e.g. Leopizzi et al. 2019; Verrecchia 1983).

EQUITY, the ratio of net equity of the year scaled by the total value of the liability side of the balance sheet, reflects the company’s current capitalisation, and it is the inverse ratio of leverage (Huang et al. 2021). EQUITY is expected to be positively associated with risk disclosure. Indeed, when EQUITY is low, firms are highly leveraged and, coherently with the proprietary cost theory, managers tend to be less transparent about sensitive information because the high level of leverage also increases risk of bankruptcy and the vulnerability of the firm to strategic, operational, financial or damage risks (Khlif and Hussainey 2016).

Additional control variables related to risk disclosure through the channel of profitability are as follows: NIM, ROE. and ROA. NIM is the net interest margin and represents the difference between the interest received and the interest paid by each bank every year: when the net interest margin increases, there is higher profitability for well-capitalised banks (Naceur and Kandil 2007). Meanwhile, ROE, the return on equity ratio, and ROA, the return on asset ratio, are used to account for management efficiency. According to signalling theory, managers of highly profitable firms have greater incentives to signal the quality of their performance and their ability to manage risks successfully, including through risk disclosure (Elshandidy et al. 2013; Iatridis 2008). According to agency cost theory, less profitable firms are more prone to provide information about why they had bad performances (Inchausti 1997) to reassure investors about good future prospects and avoid the adverse effect of litigation risks (Skinner 1994).

LIQ, the ratio of cash flows scaled by total deposits, is a measure of banks’ liquidity. Consistent with signalling theory, high-liquidity firms provide more risk-based information to convey positive messages to investors (Marshall and Weetman 2002). Moreover, banks with high liquidity ratios could be more prone to providing extensive risk-based information for competitive aims (Elzahar and Hussainey 2012). Table 1 provides a detailed description of the above-mentioned variables.

4 Results

4.1 Descriptives and Preliminary Tests

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics. The mean value of the variable ERM for the 2011–2016 period for all the Italian listed banks is quite low, suggesting that the number of risk items characterising the risk-based disclosure is extremely weak, although some companies recorded ERM index values up to 0.55. The mean value of the MTB proxy suggests that the investigated Italian-listed banks had a good market value. The mean value of the LOAN proxy indicates that lending activities represented a relevant part of the strategic business of the banks, accounting for up to 80% of the yearly total assets in some cases. The mean values of LLP and IMPL indicate that, on the whole, all the Italian listed banks suffered from high non-performing loans that damaged the quality of their credit portfolios. The mean value of EQUITY shows that, on average, banks were well capitalised. The mean value of the NIM proxy reached 1.5%, with a maximum peak of 9 percentage points. The mean values of the ROE and the ROA proxies demonstrated that the return on equity was much higher than the return on asset was, in accordance with the tendency of reaching a high banking capitalisation. The mean value of the LIQ index suggests that banks suffered from quite weak liquidity.

Table 3 shows that some variables are characterised by correlation. However, because there is no correlation between the data adopted to create them (Liu et al. 2014), such results instead express a statistical association between different phenomena that do not negatively affect the regression results.

In addition, we engage in a more in-depth investigation of the state of the art of risk and risk management disclosure in Italian listed banks during the 2011–2016 period by using content analysis to construct the yearly mean ERM variable for corresponding non-supervised and supervised banks before and after the introduction of the SSM.

To determine how the risk and risk management disclosure for Italian listed banks changed during the 2011–2016 period as a consequence of the introduction of the SSM and the control pressure exerted by the ECB through on-site/off-site inspections, we compile separate lists of those banks that underwent such inspections during 2014–2016 and those that did not. These two groups of banks are observed in two separate periods, namely before the treatment and during the treatment. As the ECB started its supervisory activities over EU credit institutions in November 2014, the period before on-site/off-site inspections goes from 2011 to 2013 and the period during on-site/off-site inspections goes from 2014 to 2016.

Tables 4 and 5 show the yearly mean ERM index for both supervised and non-supervised banks, providing a clear picture of the state of the art of the adoption and disclosure of risk management systems under each of the eight ERM perspectives mentioned above during the 2011–2013 and 2014–2016 periods. For a particularly in-depth and detailed view of the state of implementation of ERM disclosure in non-supervised and supervised banks before and after the introduction of the SSM see Appendices 1 and 2.

The results listed in the above-mentioned tables allow us to make the following argument: during the 2011–2013 period, the total amount of information relating to risk management systems in the annual reports of the supervised banks was around 27% of the maximum amount of possible risk-based disclosure (0.27). An equal lack of communication about the characteristics and functionality of risk management systems can also be found in the annual reports of the non-supervised Italian listed banking companies (0.22). The homogeneity of the ERM index values for all three consecutive administrative years (2011–2013) for supervised and non-supervised banks further shows that the Italian listed banks did not dedicate efforts to express the structure and operating methods of their adopted corporate risk management and control systems in the period immediately preceding the ECB on-site/off-site inspections. Moreover, the ERM indexes for all supervised and non-supervised companies are highly similar for 2011, 2012 and 2013, suggesting that there was no relevant tendency to implement risk disclosure over time (0.26, 0.27 and 0.27 in Appendix 1 vs 0.22, 0.22 and 0.22 in Appendix 2).

In detail, in the 3-year period (2011–2013), information relating to the topic of ‘risk identification and assessment’ was a common disclosure issue for both categories of banks (0.13 vs 0.11), immediately followed by information relating to ‘internal environment’ (0.06 vs 0.05). Specifically, many supervised banks communicated the characteristics of the structure and functionality of the ERM models to the market by presenting information on the role of the chief risk officer (CRO) and/or the risk management committee, the role of internal audits and the commitment of all members of the organisation in terms of risk identification and assessment, as well as how to identify risks relating to the issue of ‘risk identification and assessment’. Information on risk management policies—in particular, on financial, operational and market risks to which a company is exposed—was also extremely common in the risk disclosures of supervised banks. Likewise, information relating to the ‘internal environment’, the responsibility of the board, the chief executive officer (CEO) and the CRO regarding the management of business risks was frequent in the risk-based disclosures of both supervised and non-supervised banks. Particular relevance was attributed to the disclosure of the moral values guiding the bank’s operations, the training policies of bank members and the corporate organisational structure. In contrast, there was a lack of information on specific ‘risk response’ choices (0.01 vs 0.00; i.e. avoiding, reducing, sharing and accepting). Similarly, not enough mention was made of risk tolerance and ERM monitoring policy (0.01 vs 0.01) because of the great scarcity of disclosures about the effectiveness and efficiency of the risk management and control models of the banks, results about real versus expected risk management, potential inefficiencies and how to keep the model updated.

During the 2014–2016 period, the disclosure of risk management provided by both supervised and non-supervised banks was higher than it was in the previous period. Both supervised and non-supervised banks implemented an extension of the disclosure on the risk management models adopted in each year of the 3-year period (2014–2016; 0.43, 0.44 and 0.44 vs 0.25, 0.26 and 0.26). The mean ERM index for the three administrative years (2014–2016) was around 0.44 for supervised companies and 0.26 for non-supervised companies. In the 2014–2016 period, the information on risk management most presented in the annual reports of the supervised and non-supervised banks was related to ‘risk identification and assessment’ (0.19 vs 0.13) and the ‘internal environment’ (0.10 vs 0.05), while little attention was paid to the ‘risk response’ (0.01 vs 0.00) and ‘monitoring’ (0.01 vs 0.01)—just as it was for the previous 3-year period. Meanwhile, in the 2014–2016 period, non-supervised banks still provided little information about ‘objective setting’ and ‘information and communication’ (0.01). In the group of supervised banks, the overall risk disclosure was enriched with information on ‘risk identification and assessment’, ‘internal environment’, ‘control activities’ and ‘information and communication’. However, ‘risk response’ and ‘monitoring’ remained relatively little addressed, although they received greater attention than in the past. The number of banks that communicated the responsibility of the risk committee in choosing the approach to risk management and control, and the level of integration of the organisational structure needed to enable effective risk management—previously almost completely absent in the annual reports—increased as well. The number of supervised banks that reported information in their annual reports on the integrity and ethical moral values underlying their risk management policy slightly increased, while all supervised banks adopted the disclosure of the managerial positions taken towards the risk management policy and the current degree of risk exposure of the entire company.

Compared with the 2011–2013 period, in their disclosures for the 2014–2016 period, the supervised banks included information that was previously completely absent, such as internal communication channels about risk management issues, the organisational benefits of risk identification and the assessment of the adopted method. The number of banks that indicated the criteria of the risk-mapping process also increased. In addition, in the 2014–2016 period, the supervised banks enriched their risk disclosures with news about the derivative instruments used to hedge risks, interest rate risks, credit spread, exchange rate risks and equity risks.

In the group of non-supervised banks, the risk disclosures were also improved. A greater number of banks included in their annual report information on risk management models that had already been the subject of discussion in the immediately preceding 3-year period, thus aligning themselves with competitors, that is, ‘risk identification and assessment’, ‘internal environment’, followed by ‘event identification’ and ‘control activities’. Like the supervised banks, the non-supervised banks also neglected information relating to risk response and monitoring.

The above results suggest that, during the 2014–2016 period, the quantity of risk items presented in the annual reports increased in both supervised and non-supervised banks, with positive effects on the number of disclosure items about risks and risk management systems. Notwithstanding, as highlighted in Tables 4 and 5, the risk disclosure of supervised banks experienced an overall increase that was significantly greater than that recorded in non-supervised banks (63.3% vs 20.49%). For each of the recognised ERM topics, the 3-year rate of change of the ERM index of the supervised banks was higher than that for the non-supervised banks. Hence, the intensity of the implementation of risk disclosure of banks that underwent on-site/off-site inspections during the 2014–2016 period was ultimately far greater than that for banks that did not undergo inspection.

4.2 Regression Results and Robustness Tests

Table 6 gives the overall results for the random-effects GLS regression, the main research model. The estimated coefficient for SSMi is significantly positive, suggesting that there has been an increase in the number of risk and risk management disclosure items for the Italian listed banks after the introduction of the SSM in 2014. The results confirm that firm behaviour is deeply affected by the characteristics of the institutional context, as explained by the institutional theory of Di Maggio and Powell (1983). Our results demonstrate that, under the same regulatory pressure (i.e. SSM establishment), banks investigated are encouraged to increase the number of risk items inside their risk disclosure. In addition, we contribute to investigating those specific factors of institutional context that can influence banking behaviours, also called ‘country-level factors’ (Bischof et al. 2015; Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2008; Elamer et al. 2019; Linsley and Shrives 2005b; Oliveira et al. 2011a, b; Polizzi and Scannella 2020, Polizzi et al. 2020), highlighting the crucial role of regulatory and supervisory components. Likewise, our results demonstrate how the endorsement of a new stricter regulation can drastically change banking behaviour in the future. Previous studies showed that the issuance of Basel II requirements implemented the banking risk disclosure (Bischof et al. 2015; Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2008; Linsley and Shrives 2005b; Oliveira et al. 2011a, b). The estimated coefficient for SUPERVit is significantly positive, suggesting that those banks that underwent ECB on-site/off-site inspections disclosed more risk items in their annual reports. Coherent with the previous literature, such results suggest that the strengthening of the regulatory oversight performed after the introduction of the SSM through the ECB on-site/off-site inspections has encouraged an increase in risk and risk management disclosure (Beretta and Bozzolan 2004; Liebenberg and Hoyt 2003; Rajab and Handley-Schachler 2009).

Our results confirm the empirical evidence provided by previous studies by Barakat and Hussainey (2013), Bischof et al. (2015) and Elamer et al. (2019), which demonstrated that, when control pressure increases, firms provide more holistic and structured risk management disclosures. Hence, coherent with one orientation of the accounting literature on risk disclosure (Barakat and Hussainey 2013; Beretta and Bozzolan 2004; Bischof et al. 2015; Elamer et al. 2019), our findings suggest that the enforcement of supervisory powers for international banking authorities positively influences banks’ behaviour in terms of risk and risk management disclosure.

The F test confirmed the goodness of fit of the random-effects GLS regression. In addition, the Breusch and Pagan Lagrangian multiplier test for random effects corroborated the choice of a random-effects regression over a multiple ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Despite the Hausman test’s suggestion to adopt random-effects GLS regression rather than fixed-effects regression, this study also performs a fixed-effects regression as a robustness test. According to results reported in Table 7, the above-mentioned evidence is fully confirmed.

To investigate whether there is a statistically significant difference between the mean values of the ERM index (ERM) in sampled banks before (group 0) and after (group 1) the introduction of the SSM (SSMit), we perform the independent t-test. The results, shown in Table 8, demonstrate that the difference in the mean ERM of the same banks before and after the introduction of the SSM is −0.061 and statistically significant using a two-tailed test (t(184) = −3.46, p < 0.005). Likewise, to investigate whether there is a statistically significant difference between the mean values of the ERM index (ERM) in the sub-samples of banks undergoing (group 1) and not undergoing (group 0) the ECB on-site/off-site inspections (SUPERVit), we perform the independent t-test. The results of this test, shown in Table 9, demonstrate that the difference in the mean ERMit of those banks that underwent ECB on-site/off-site inspections and those who did not is −0.137 and statistically significant using a two-tailed test (t(184) = −5.33, p < 0.005).

5 Discussion and Conclusions

Risk disclosure has strategic importance for the efficiency of financial markets and overall financial stability (Scannella 2018). Because the current evidence is not sufficiently clear, the increasing interest of standard setters and regulators in risk disclosure encourages academics and professionals to go deeper into investigating such topics (Oliveira et al. 2011a, b). Moving on from the criticisms raised over the past few years by many academics and practitioners who shared the view that current risk disclosure is inadequate and not useful for decision-making, this chapter examines issues relating to the number of risk and risk management disclosure items in annual reports after the introduction of the SSM, a topic that has aroused considerable attention and interest (Masciandaro 2015; Mesnard et al. 2016).

Although several studies have provided empirical evidence on the correlation between the level of risk disclosure and regulations, there is still a substantial lack of evidence about what really happens to corporate risk-based disclosure after the strengthening of supervisory pressure, especially after the latest revolutionary developments of the supervisory mechanisms in the EU. To investigate whether the number of risk and risk management disclosure items of Italian listed banks increased after the introduction of the SSM in November 2014, as well as whether those banks that underwent ECB on-site/off-site inspections implemented the number of risk-based disclosure items more to a greater extent compared with banks that did not undergo such inspection in the same period (2014–2016), this study performs a random-effects GLS regression and a fixed-effects regression.

The findings showed that the number of risk items increased after the effective establishment of the SSM in 2014. Such results are in accordance with those of the previous literature, which suggested that stricter regulations are associated with better risk disclosure (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2008; Oliveira et al. 2011a, b). Further, our results confirmed that the trend of implementing risk-based disclosure is stronger for those banks that underwent ECB direct inspections during the 2014–2016 period. In accordance with previous studies (Barakat and Hussainey 2013; Bischof et al. 2015; Elamer et al. 2019), these findings provide empirical evidence that banks that are subject to the control of powerful and independent supervisory authorities provide more holistic and structured risk management disclosures.

The contribution of this chapter to the international debate on risk disclosure in the banking context is threefold. First, this study fills a previous literature gap. With the establishment of SSM, scholars have developed a fervent interest in researching the effect of the new requirements on banks, such as the performance of the credit default swaps (Pancotto et al. 2020) and lending activities (Fiordelisi et al. 2017). However, whether the establishment of the SSM has also been accompanied by an increasing risk disclosure has not been investigated before. Our study provides empirical evidence that the establishment of SSM was followed by the increase of risk and risk management disclosure in the investigated Italian banking context. Second, to the best of our knowledge, the current literature has not yet clarified the role of supervisory authorities in guiding risk disclosure. Hence, with the above-mentioned results, this chapter covers this gap in the ongoing international debate. Third, this is the first study to examine the state of the art of risk reporting in the Italian banking context since the birth of the European Banking Union.

This study has practical implications for regulators, banks and practitioners. First, our work illustrates that the endorsement of a new regulation has been accompanied by a change in banking behaviours in terms of risk disclosure. This evidence highlights the importance of regulatory pressure to drive banks towards better transparency of risk disclosure. In addition, this study offers regulators a better understanding of how much risk transparency has changed in the Italian context after the SSM establishment. Second, this chapter provides a clearer picture of two important determinants of risk disclosure within the institutional context, such as stricter regulation and supervisory pressure. Third, this study suggests to practitioners, such as standard setters and supervising authorities, the crucial role of supervisory pressure on banking behaviour. Overall, this chapter offers regulators, standard setters and supervisory authorities some insights for further reflection on potential pathways to follow to increase the quality and transparency of risk management disclosures in the banking context.

The limitations of this chapter include the investigation of a specific banking context (i.e. the Italian context) during a narrow timeframe (i.e. 2011–2016). As a consequence, the results of this study cannot be extended to different geopolitical contexts or to other historical periods because the investigated Italian setting is unique in both respects.

Notes

- 1.

‘Risk is the possibility of loss of injury and the degree of probability of such loss’ (Kaplan and Garrick 1981, p. 12). ‘Risk is probability and consequence’ (Kaplan and Garrick 1981, p. 13). ‘Risk management is a mechanism for managing exposure to risk that enables us to recognise the events that may result in unfortunate or damaging consequences in the future, their severity, and how they can be controlled. A working definition of risk management that applies generally […] could be: the identification, analysis, and economic control of those risks which can threaten the assets or earnings capacity of an enterprise’ (Dickson 1995, p. 75).

- 2.

The aim of such intervention was to ‘encourage market discipline by developing a set of disclosure requirements which allow market participants to assess […] risk exposures, risk-assessment processes and hence the capital adequacy of the institution’ (BCBS 2004, p. 226).

- 3.

‘The Committee is aware that supervisors have different powers available to them to achieve the disclosure requirements. […] Under safety and soundness grounds, supervisors could require banks to disclose information. Alternatively, supervisors have the authority to require banks to provide information in regulatory reports. Some supervisors could make some or all of the information in these reports publicly available. Further, there are a number of existing mechanisms by which supervisors may enforce requirements’ (BCBS 2004, p. 226).

- 4.

‘Significant’ European banks account for more than 80% of the banking assets in the EU, and thus, they constitute a substantial part of the EU financial market (Roldán and Lannoo 2014). According to ECB (2014), ‘[a] credit institution will be considered significant if any one of the following conditions is met: 1. The total value of its assets exceeds €30 billion or unless the total value of its assets is below €5 billion – exceeds 20% of national GDP; 2. it is one of the three most significant credit institutions established in a Member State; 3. it is a recipient of direct assistance from the European Stability Mechanism; 4. the total value of its assets exceeds €5 billion and the ratio of its cross-border assets/liabilities in more than one other participating Member State to its total assets/liabilities is above 20%’.

- 5.

The first comprehensive assessment performed by the ECB in 2014 involved 130 banks in the euro area (including Lithuania), covering approximately 82% of total bank assets. It consisted of a supervisory risk assessment, an asset quality review and a stress test.

- 6.

All data about risk management systems are manually collected from the annual reports of Italian listed banks.

- 7.

‘The release of accounting statistics about a firm may be useful to competitors, shareholders or employees in a way which is harmful to a firm’s prospects even if (or perhaps because) the information is favourable’ (Verrecchia 1983, p. 182).

- 8.

The group of supervised banks includes the following: Banca Carige spa, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena spa, Banca Popolare di Sondrio, Credito Emiliano spa, Intesa Sanpaolo spa, Mediobanca, UniCredit spa, Unione di Banche Italiane spa. The group of non-supervised banks includs the following: Banco BPM spa, Poste Italiane spa, BPER Banca spa, Banca Mediolanum spa, Banca FinEco spa, Banca Piccolo Credito Valtellinese spa, Banco di Desio e della Brianza spa, Banco di Sardegna spa, Banca Generali spa, Banca Ifis spa, Azimut Holding spa, Banca Farmafactoring spa, Nexi spa, Banca Sistema spa, Illimity Bank spa, Banca Profilo spa, Banca Finnat Euramerica spa, Banca Intermobiliare di Investimenti e Gestioni, doValue spa, Gruppo Mutuionline spa, First Capital spa, Conafi Prestito spa and Mediocredito Europeo spa.

- 9.

The random effect regression model is the main research model, while the fixed-effects model serves as the robustness test. Both the random- and fixed-effects regression models are statistically significant, as demonstrated in more detail in Tables 6 and 7. However, the choice for preferring the random-effects regression as main research model and the fixed-effects regression as robustness test has been suggested by the results of the Hausman Test (Prob>CHI2 = 0.7243) and by the Breusch and Pagan Lagrangian Multiplier test for random effects (chibar2(01) = 48.31; Prob>chibar2 = 0.0000).

- 10.

This study does not analyse how much the risk information disclosure matches with the COSO (2004) ERM framework, but it only considers the quantitative dimension of risk disclosure by searching for the mention of some risk items suggested by the COSO (2004) in the ERM framework, the only reference point for a risk disclosure that banks had during the 2011–2016 period.

References

Alexander K (2014) The ECB and banking supervision: building effective prudential supervision? Yearb Eur Law 33(1):417–432. https://doi.org/10.1093/yel/yeu018

Amran A, Bin AMR, Hassan MHC (2009) Risk reporting: an exploratory study on risk management disclosure in Malaysian annual reports. Manag Audit J 24(1):39–57. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686900910919893

Barakat A, Hussainey K (2013) Bank governance, regulation, supervision, and risk reporting: evidence from operational risk disclosures in European banks. Int Rev Financ Anal 30:254–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2013.07.002

Barth JR, Dopico LG, Nolle DE, Wilcox JA (2002) Bank safety and soundness and the structure of bank supervision: a cross-country analysis. Int Rev Financ 3(3/4):163–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-412X.2002.00037.x

Barth JR, Caprio G Jr, Levine R (2004) Bank regulation and supervision: what works best? J Financ Intermed 13(2):205–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2003.06.002

Barth JR, Caprio G Jr, Levine R (2006) Rethinking bank regulation: till angels govern. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 177

Barth JR, Lin C, Ma Y, Seade J, Song FM (2013) Do bank regulation, supervision and monitoring enhance or impede bank efficiency? J Bank Financ 37(8):2879–2892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.04.030

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (1998) Enhancing Bank Transparency – public disclosure and supervisory information that promote safety and soundness in banking systems. https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs41.pdf

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2000) Principles for the Management of Credit Risk. https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs75.pdf

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2004) Supervisory Review Process and Market Discipline. https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs128c.pdf

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2019) Overview of Pillar 2 supervisory review practices and approaches. https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d465.pdf

Beatty A, Liao S (2014) Financial accounting in the banking industry: a review of the empirical literature. J Account Econ 58(2–3):339–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2014.08.009

Beaver W, Eger C, Ryan S, Wolfson M (1989) Financial reporting, supplemental disclosures, and bank share prices. J Account Res 27(2):157–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2491230

Beltratti A, Stulz RM (2012) The credit crisis around the globe: why did some banks perform better? J Financ Econ 105(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.12.005

Beretta S, Bozzolan S (2004) A framework for the analysis of firm risk communication. Int J Account 39(3):265–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2004.06.006

Berry-Stolzle TR, Jianren X (2018) Enterprise risk management and the cost of capital. J Risk Insur 85(1):159–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/jori.12152

Bischof J (2009) The effects of IFRS 7 adoption on bank disclosure in Europe. Account Eur 6(2):167–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480903171988

Bischof J, Daske H, Elfers F, Hail L (2015) A tale of two regulators: risk disclosures, liquidity, and enforcement in the banking sector. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2580569

Boudriga A, Taktak NB, Jellouli S (2009) Banking supervision and nonperforming loans: a cross-country analysis. J Financ Econ Policy 1(4):286–318. https://doi.org/10.1108/17576380911050043

Buckby S, Gallery G, Ma J (2015) An analysis of risk management disclosures: Australian evidence. Manag Audit J 30(8/9):812–869. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-09-2013-0934

Chen L, Zhao X (2006) On the relation between the market-to-book ratio, growth opportunity, and leverage ratio. Financ Res Lett 3(4):253–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2006.06.003

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (2004) Enterprise risk management – integrated framework. https://www.coso.org/Pages/erm-integratedframework.aspx

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (2016) Enterprise risk management – aligning risk with strategy and performance. https://www.coso.org/Pages/default.aspx

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (2017) Enterprise risk management – integrating with strategy and performance. https://www.coso.org/Pages/default.aspx

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (2018) Enterprise Risk Management – Applying enterprise risk management to environmental, social and governance-related risks. https://www.coso.org/Documents/COSO-WBCSD-ESGERM-Guidance-Full.pdf

Darvas Z, Pisani-Ferry J, Wolff GB (2013) Europe’s growth problem (and what to do about it). Policy Briefs 776(3):1–8

Delis MD, Staikouras PK (2011) Supervisory effectiveness and bank risk. Rev Financ 15(3):511–543. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfq035

Demirgüç-Kunt A, Detragiache E, Tressel T (2008) Banking on the principles: compliance with Basel Core Principles and bank soundness. J Financ Intermed 17(4):511–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2007.10.003

Desender KA (2010) Essays on ownership structure, corporate governance and corporate finance. Dissertation, Universitat Autonòma de Barcelona

Desender KA, Lafuente E (2009) The influence of board composition, audit fees and ownership concentration on enterprise risk management. SSRN Electron J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1495856

Di Maggio P, Powell W (1983) The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am Sociol Rev 48:147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

Dickson G (1995) Principles of risk management. Qual Health Care 4:75–79

Dobler M (2008) Incentives for risk reporting—a discretionary disclosure and cheap talk approach. Int J Account 43(2):184–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2008.04.005

Elamer AA, Ntim CG, Abdou H, Zalata A, Elmagrhi MH (2019) The impact of multi-layer governance on bank risk disclosure in emerging markets: the case of Middle East and North Africa. Account Forum 43(2):246–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/01559982.2019.1576577

Elshandidy T, Fraser I, Hussainey K (2013) Aggregated, voluntary, and mandatory risk disclosure incentives: evidence from UK FTSE all-share companies. Int Rev Financ Anal 30:320–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2013.07.010

Elzahar H, Hussainey K (2012) Determinants of narrative risk disclosures in UK interim reports. J Risk Financ 13(2):133–147. https://doi.org/10.1108/15265941211203189

European Central Bank (ECB) (2014) Guide to banking supervision. https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/pdf/ssmguidebankingsupervision201411.en.pdf

European Central Bank (2018) SSM Supervisory Manual European banking supervision: functioning of the SSM and supervisory approach. https://www.bankingsupervision.europa.eu/ecb/pub/pdf/ssm.supervisorymanual201803.en.pdf?42da4200dd38971a82c2d15b9ebc0e65

Ferran E, Babis VSG (2013) The European single supervisory mechanism. J Corp Law Stud 13(2):255–285. https://doi.org/10.5235/14735970.13.2.255

Fiordelisi F, Ricci O, Lopes S, Saverio F (2017) The unintended consequences of the launch of the single supervisory mechanism in Europe. J Financ Quant Anal 52(6):2809–2836. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109017000886

Gauci G, Grima S (2020) The impact of regulatory pressures on governance on the performance of public banks’ with a European Mediterranean region connection. Eur Res Stud J XXIII(2):360–387. https://doi.org/10.35808/ersj/1598

Ghezzi F, Magnani P (1998) L’applicazione della disciplina antitrust comunitaria al settore bancario. In: Polo M (ed) Industria Bancaria e Concorrenza. Il Mulino, Bologna, pp 259–328

Gualandri E (2011) Basel 3, Pillar 2: the role of banks’ internal governance and control function. Cefin Working papers 27. https://iris.unimore.it/retrieve/handle/11380/1197439/254678/CEFIN-WP27.pdf

Hawley AH (1968) Human ecology, population, and development. In: Sills DL (ed) International encyclopedia of the social sciences. Macmillan, New York, pp 11–25

Hirtle B, Kovner A, Plosser M (2020) The impact of supervision on bank performance. J Financ 75(5):2765–2808. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12964

Huang Q, De Haan J, Scholtens B (2021) Does bank capitalization matter for bank stock returns? North Am J Econ Financ 52:101171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2020.101171

Iatridis G (2008) Accounting disclosure and firms’ financial attributes: evidence from the UK stock market. Int Rev Financ Anal 17(2):219–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2006.05.003

Inchausti BG (1997) The influence of company characteristics and accounting regulation on information disclosed by Spanish firms. Eur Account Rev 6(1):45–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/096381897336863

Kaplan S, Garrick BJ (1981) On the quantitative definition of risk. Risk Anal 1(1):11–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1981.tb01350.x

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Matruzzi M (2008) Governance matters VII: aggregate and individual governance indicators, 1996–2007 World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4654. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1148386

Khlif H, Hussainey K (2016) The association between risk disclosure and firm characteristics: a meta-analysis. J Risk Res 19(2):181–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2014.961514

KPMG (2019) L’evoluzione del Sistema bancario italiano. Gli indicatori chiave del settore bancario negli ultimi dieci anni. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/it/pdf/2019/02/Evoluzione-sistema-bancario-italiano.pdf

Lajili K, Zéghal D (2005) A content analysis of risk management disclosures in Canadian annual reports. Can J Adm Sci 22:125–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-4490.2005.tb00714.x

Leopizzi R, Iazzi A, Venturelli A, Principale S (2019) Nonfinancial risk disclosure: the “state of the art” of Italian companies. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 27(1):358–368. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1810

Liebenberg AP, Hoyt RE (2003) The determinants of enterprise risk management: evidence from the appointment of chief risk officers. Risk Manag Insur Rev 6(1):37–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/1098-1616.00019

Linsley PM, Shrives PJ (2005a) Transparency and the disclosure of risk information in the banking sector. J Financ Regul Compliance 13(3):205–214. https://doi.org/10.1108/13581980510622063

Linsley PM, Shrives PJ (2005b) Examining risk reporting in UK public companies. J Risk Financ 6(4):292–305. https://doi.org/10.1108/15265940510613633

Linsley PM, Shrives PJ, Crumpton M (2006) Risk disclosure: an exploratory study of UK and Canadian banks. J Bank Regul 7(3/4):268–282. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jbr.2350032

Liu C, Yuen YC, Yao LJ, Chan SH (2014) Differences in earnings management between firms using US GAAP and IAS/IFRS. Rev Acc Financ 13(2):134–155. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAF-10-2012-0098

Maffei M, Aria M, Fiondella C, Spanò R, Zagaria C (2014) (Un)useful risk disclosure: explanations from the Italian banks. Manag Audit J 29(7):621–648. https://doi.org/10.1108/MAJ-11-2013-0964

Marshall A, Weetman P (2002) Information asymmetry in disclosure of foreign exchange risk management: can regulation be effective? J Econ Bus 54(1):31–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-6195(01)00058-3

Masciandaro D (2015) SSM: Il calcio d’inizio di una nuova partita in Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) Glossario. https://st.ilsole24ore.com/st/glossarioBCE/files/Il_Single_Supervisory_Mechanism.pdf

Meeker LG, Gray L (1987) A note on non-performing loans as an indicator of asset quality. J Bank Financ 11(1):161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(87)90028-8

Mesnard B, Margerit A, Power C, Magnus M (2016) Non-performing loans in the Banking Union: stocktaking and challenges. https://blog.qualco.eu/hubfs/Q2%202018/April/BLOG%20POST%203%20/IPOL_BRI(2016)574400_EN.pdf

Moody’s Analytics (2011) Implementing Basel III: challenges, options and opportunities. https://www.moodysanalytics.com/-/media/whitepaper/2011/11-01-09-implementing-basel-iii-whitepaper.pdf

Mukhiba H, Nurkhin A, Rohman A (2020) Corporate governance mechanism and risk disclosure by Islamic banks in Indonesia. Banks Bank Syst 15(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.21511/bbs.15(1).2020.01

Naceur SB, Kandil M (2007) The impact of capital requirements on banks’ cost of intermediation and performance: the case of Egypt. J Econ Bus 61(1):70–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2007.12.001

Neifar S, Salhi B, Jarboui A (2020) The moderating role of Shariah supervisory board on the relationship between board effectiveness, operational risk transparency and bank performance. Int J Ethics Syst 36(3):325–349. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOES-09-2019-0155

Oliveira J, Rodrigues LL, Craig R (2011a) Risk-related disclosures by non-finance companies: Portuguese practices and disclosure characteristics. Manag Audit J 26(9):817–839. https://doi.org/10.1108/02686901111171466

Oliveira J, Rodrigues LL, Craig R (2011b) Voluntary risk reporting to enhance institutional and organizational legitimacy: evidence from Portuguese banks. J Financ Regul Compliance 19(3):271–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/13581981111147892

Pancotto L, Gwilym O, Williams J (2020) Market reactions to the implementation of the Banking Union in Europe. Eur J Financ 26(7–8):640–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2019.1661264

Panfilo S (2019) (In)consistency between private and public disclosure on enterprise risk management and its determinants. In: Linsley P, Shrives P, Wieczorek-Kosmala M (eds) Multiple perspectives in risk and risk management. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics, Cham, pp 87–123

Polizzi S, Scannella E (2020) An empirical investigation into market risk disclosure: is there room to improve for Italian banks? J Financ Regul Compliance 28(3):465–483. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFRC-05-2019-0060

Polizzi S, Scannella E, Suárez N (2020) The role of capital and liquidity in bank lending: are banks safer? Glob Policy 11:28–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12750

PricewaterhouseCoopers (2008) Does ERM matter? Enterprise risk management in the insurance. http://www.pwc.com/gx/en/insurance/pdf/erm_survey.pdf

Quintyn M, Taylor MW (2002) Regulatory and supervisory independence and financial stability. International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 02/46. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/30/Regulatory-and-Supervisory-Independence-and-Financial-Stability-15679

Rajab B, Handley-Schachler M (2009) Corporate risk disclosure by UK firms: trends and determinants world. World Rev Entrep Manag Sustain Dev 5(3):224–243. https://doi.org/10.1504/WREMSD.2009.026801

Roldán JM, Lannoo K (2014) ECB banking supervision and beyond. https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/ecb-banking-supervision-and-beyond/

Scannella E (2018) Market risk disclosure in banks’ balance sheets and the pillar 3 report: the case of Italian banks. In: García-Olalla M, Clifton J (eds) Contemporary issues in banking. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 53–90

Scott WR (1994) Conceptualizing organizational fields: linking organizations and social system. In: Derlien H-U, Gerhardt U, Scharpf FW (eds) Systemrationalitat und partialinteresse. Nomos Verlagsgescellschaft, Baden-Baden, pp 203–221

Skinner D (1994) Why firms voluntarily disclose bad news. J Account Res 32(1):38–61