Abstract

In the current context, marked by the challenges of the digital transformation, the climate emergency, the risks of the Covid-19 pandemic and the economic and health crisis, resilience emerged as a concept explaining how societies, systems, and subsystems can respond to shocks and better manage the inherent risks that are constantly changing. With the digital transformation and the increasing use of the internet by organisations, relational capital has emerged as one of the components of intellectual capital with greater relevance for the resilience and agility of organisations. Through the most recent literature review, this study explores the relationship between relational capital and firms’ resilience indicators. The results provide empirical evidence for the positive relationship between the two concepts and present the basis for developing an auditing framework of organisational resilience.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) started a revolution in business models. Companies, in all sectors, have been forced to adapt their organisational processes, people management, customer, and supply chain management and even their interaction with the application of public policies. This challenge is indicative of new times (Sneader & Singhal, 2020).

Large, medium, and small organisations have gone to great lengths to find solutions, optimise production and create alliances with other organisations operating in the same sector to overcome emerging challenges together, and most of these initiatives have had a positive impact (Mariano, 2021).

The pandemic appears to have changed, mainly how consumers shop and how supply chains and value chains are organised. In this scenario, the most resilient companies, driven by the accelerated growth of digital transformation, were forced to gain elasticity, re-adapt, reinvent themselves, become agile, and develop new characteristics that seem to make them stronger (Verhoef et al., 2021).

The literature and empirical observation seem to indicate a relationship between the development of companies’ relational capital (RC) and their resilience, as it points Walecka (2021). That is, companies with better performances in relational capital have a better capacity to adapt to contexts of crisis and uncertainty in what we currently live. Thus, it is clear that companies establish relationships seeking to minimise risks. Through cooperation with unknown partners, they consciously create their relational capital.

Bolisani and Bratianu (2017) and Keszey (2018) note that to respond to hyper turbulent environments, organisations cultivate a knowledge ecosystem that promotes opportunities for knowledge exchange among employees and allows dynamic knowledge exchange activities to occur and evolve as environmental circumstances so require.

Considering this context, García and Bounfour (2014) report a growing body of empirical evidence that proves the contribution of the RC as a knowledge asset capable of boosting the company’s capacities to intensify the absorption of intangible resources. In the context of external relations, Relational Capital is identified as a research gap, as pointed out by Buenechea-Elberdin et al. (2018).

In this sense, Venugopalan et al. (2018) recommend that managers develop RC indicators based on the nature of their businesses. To this end, they suggest that time and effort should be invested in nurturing and maintaining relationships with its internal and external audiences. This practice should be seen as an organisational strategy of considerable importance in a knowledge-based economy.

Research suggests a positive linear and relationship between RC and resilience; see, for example Polyviou et al. (2019), Teo et al. (2017) and Walecka (2021). The authors argue that CR results in superior access to resources and information maintained by the relationships between organisations. At the same time, resilience is associated with improved organisational capabilities to survive, adapt, and grow when faced with environments of change, uncertainty, and extreme crises. However, gaps arise in the understanding of how the RC can facilitate the capacity for organisational resilience.

In this sense, this chapter’s primary objective is to understand how the development of relational capital influences organisational resilience in times of crisis. Besides, it is intended to identify the determining factors in these resilience processes and present the basis for developing a framework that allows auditing organisational resilience.

Our research question seeks to answer how the factors of the RC can be facilitators of the capacities of organisational resilience. This initial study is exploratory in nature is based on the analysis of the state of the art of literature of relational capital and the literature of organisational resilience, completed by the literature search that relates the two concepts.

2 Methodology

To achieve the objectives of this article, exploratory research strategies were used in the literature. According to Creswell (2010), this type of research aims to explain and expand the understanding of the causes and consequences of this phenomenon. The exploratory strategy is especially advantageous for studies that aim to build an exploratory framework on little-explored topics.

Through search and analysis of the papers for this study, the authors intend to collect the current research that relates relational capital with resilience to identify and understand the overall landscape in this field of study.

Data were collected through a literature review carried out in the international databases Scopus, Web of Science and Ebsco. Time limits were not considered to include this review as many studies as possible.

A structured keyword search was the basis for the search for articles for this research. The searched keywords on these databases were “relational capital” and “organisational resilience.”

The identified articles were analysed qualitatively, using the content analysis method, with the recurrence of themes. The indicators that characterise or form the RC and organisational resilience were identified and delimited. These exploratory findings were analysed based on the assumption that using relatively systematic procedures, hypotheses of relationships relevant to the phenomenon proposed in this research could be identified.

In this sense, indicators incorporated in the concepts of RC and organisational resilience were gathered. After linking these topics, a framework was proposed to serve as a basis for expanding studies on the theme.

3 Literature Review

This section presents the concepts and indicators identified through articles of the international databases Scopus, Web of science and Ebsco.

Relational Capital Concepts

Relational Capital (RC) is understood as an intangible resource of the organisation capable of generating knowledge from its relations with its strategic partners. Stewart (1998) points out that the RC is based on the idea that companies are not an isolated system but belong to an interconnected system, dependent on their relationship with the external environment (Knight, 1999).

However, as Bontis (1996) proposed, initially, the RC construct was used to identify issues related only to the client’s capital value. Academic and empirical contributions advance this understanding and begin to recognise the intangible value of the relationships that a company maintains beyond customers and begin to consider relationships as partnerships and strategic alliances, as advocated by Stewart (1998), and as the assets of the market, which is pointed out by Brooking (1996). In this sense, Stewart (1998) considers RC to be a valuable intangible asset for the organisation, as it refers to the long-lasting relationships of companies with their strategic partners, capable of creating value for the company. This value can be measured from the value of the strategic alliances established, collaborative relationships, business partnerships, joint ventures and relationships with customers, employees, suppliers, and associations.

Edvinsson and Malone (1997) corroborate with the authors and affirm that the RC deals with the organisation’s internal and external relations with employees, customers, suppliers, universities, associations, unions, strategic alliances, collaborative relationships, competitors, and partnerships capable of expanding the company’s market share.

One of the pioneers in explaining the importance of relational capital was Leif Edvinsson. As the corporate director at Skandia AFS, this author explained the concept of intellectual capital using a metaphor. The author compares a company to a fruit tree in which the roots that provide long-term sustainability are intellectual capital, and the fruits are financial results. According to the author, it must have qualified human capital and relational capital to satisfy customers for a company to develop good products and services. Relational capital contains relationships with customers, suppliers, shareholders, or partners (Edvinsson, 1997, 2002; Edvinsson & Malone, 1997).

In 2013, on the occasion of reflections from 21 years of IC practice and theory, Edvinsson reinforced the idea of the importance of relational capital by referring that “The critical question became how to build a bridge between brains inside the organisation, known as human capital, and brains outside, known as relational capital.” (Edvinsson, 2013, p. 168). For the author, the main challenge is “understanding and development of the value of networks” (Edvinsson, 2013, p. 168) because it is in the networks that the company’s adaptability lies. The author thus makes an approximation between the concept of relational capital and resilience.

More recently, the author states that in a context dominated by artificial intelligence, the core of intellectual capital appears to be in the “relational capital dimensions, the in-between space of connectivity, and contactivity” (Ordóñez de Pablos & Edvinsson, 2020, p. 295). Intellectual capital is often the primary driver of an organisation’s success and survival, and therefore relational capital as a source of connectivity and innovation becomes a crucial capital (Warkentin et al., 2021).

Similarly, Welbourne and Pardo-del-Val (2008) find that companies with high-performance levels can negotiate with other actors and develop collaboration agreements, placing a high value on RC. The authors also note that organisational performance improves when the RC configuration is adapted to change and resource needs, so the RC impacts organisational adaptability in turbulent scenarios.

Thus, it is possible to analyse that the amount of knowledge acquired by a company depends on RC factors. As mentioned by Liu et al. (2010), the amount of knowledge acquired by a company depends on three critical dimensions of RC: the quality of the relationship in terms of the trust, the level of transparency between the firm and partners, and the partner’s level of interaction. Buenechea-Elberdin et al. (2018) corroborate this idea and understand that the RC can be understood by internal relations, which is knowledge, embedded and available to the company through the webs of relations between its members; and external relations, which includes cutting-edge knowledge and resources that come from the company’s external relations, is seen as connections with customers, suppliers, partners and the local community.

Still, Ho et al. (2019) note that companies that strengthen their RC through frequent interaction with their partners, mutual trust, and mutual commitment reduce the ambiguity of knowledge, which helps them to enhance knowledge capabilities and resources.

Walecka (2021) notes that establishing cooperation with different groups of stakeholders and creating RC in a company is an increasingly relevant process for reducing the uncertainty of economic activities. In this sense, the ability to create economic relationships and establish alliances seems to increase the organisation’s flexibility, which significantly increases its competitiveness and determines its resilience in times of crisis.

However, as demonstrated (e.g. Matos et al., 2020; Osinski et al., 2017), the management of intellectual capital presupposes the integration between the various components of this intangible asset (human capital, structural capital, and relational capital), that is, RC seems to have a significant impact on organisations’ resilience, but per se it just should not be enough for an organisation to be resilient.

Relational Capital

Indicators Seminal studies such as Roos and Roos (1997), Stewart (1998) and Sveiby (1998) point to the RC as one of the components of the intellectual capital, understood through the internal and external relations that the organisation establishes with its employees, customers, consumers, and with suppliers.

Knight’s (1999) theoretical perspective analyses the RC based on strategic alliances, collaborative relationships between companies and partnerships that companies establish with the community, associations, and universities, namely, its stakeholders.

Capello and Faggian (2005) pointed out the external factors of the RC for the overflow of knowledge, which refers to the positive externalities that companies receive in terms of knowledge of the environment in which they operate. The RC is characterised by the organisation’s proximity to its stakeholders, the interaction and shared common values, explicit cooperation with its suppliers and customers, and the public and private partnerships with its environment.

Also, Rodrigues et al. (2009) analyse the RC as a construct capable of measuring the value generated by the organisation’s relations with its customers, suppliers, alliances, shareholders, external agents, industrial and governmental associations and stakeholders. Thus, it is understood that factors such as collaboration networks with customers, suppliers, collaborative networks with competitors, knowledge institutions such as universities, the R&D partnerships enable the highest performance and the ability to innovate in the organisation.

Lu and Wang (2012) consider that interfirm cooperation has gained importance in the relationships between buyers, suppliers, and business partners since proximity between companies can be regarded as a strategic alternative that allows organisations to combine valuable resources and knowledge to achieve superior performance long-term. According to the authors, factors related to trust, cooperation, and the intense relationship between networked companies allow companies to rationalise their management activities and generate a competitive advantage.

García and Bounfour (2014) analysed the RC based on cooperation between companies as a fundamental resource for innovation in 5813 companies from 13 countries in Europe. The findings corroborate that firm’s cooperative relationship with its requirements in innovation activities and the relationship developed with other types of partners such as organisations in a conglomerate, joint ventures, customers, universities, consultants, or government institutions, and participation in programs with the government leverage as a resource for firms.

For Engelman et al. (2016), the ability to collaborate, to diagnose and solve problems, sharing information, interact and exchange employee ideas with people from different areas of the company, such as partnerships with customers, suppliers, alliance partners, to develop new solutions, generates the application of knowledge from one area of the company to problems and opportunities that arise in another area and make it possible to expand organisations’ innovative resources, in turbulent environments such as developing countries like Brazil.

Research by Yoo et al. (2016) also confirms that RC elevated by factors such as good relationships of trust with alliance partners—a process of communication and information sharing between strengthened alliance partners and companies’ commitment—enables an improvement in the company’s performance.

Andreeva and Garanina (2016) and Buenechea-Elberdin et al. (2018) consider indicators such as the company’s internal relations with the R&D, marketing and production departments; the frequent collaboration of employees to solve problems; internal cooperation; the company’s relations with external stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers and partners; and the frequency of the company’s collaboration and its external stakeholders as factors of the RC that enable the company to perform at a higher level.

However, as proposed by Ho et al. (2019), it is observed that the RC is analysed as a multidimensional relative construct to a sequence of positive interactions between companies in a state of cooperation. The authors use measures that analyse interaction with the partner, mutual trust and reciprocal commitment.

When analysing the impact of the RC as a factor that enhances the capacity for organisational resilience in cases of crises, Walecka (2021) considering the following criteria: the relevant market information of a particular group of investigated parties; limited bidding for a specific group and prepared matches; the reduced influence of a certain group of stakeholders on the quality of the company’s products and processes; the long-term cooperation released; the trust by a group of stakeholders; and the benefits of cooperation. To the authors, the research findings prove that the high RC value allows conditions for building organisational resilience in the face of a crisis.

Through this theoretical and exploratory review, recurrent indicators were identified that analyse the RC as a factor capable of leveraging organisational resources such as performance, innovation, and resilience. The principal factors identified are (1) The quality of the companies’ relationships with their stakeholders (2) The strategy and benefits of long-term cooperation between companies with their customers and suppliers (3) The collaboration between organisations to achieve common goals (4) The trust created with the interested groups (5) the frequency of communication between companies and stakeholders to share information and knowledge about the sector.

Resilience Concepts

Through the most recent literature review, research on resilience concepts was carried out that would allow us to identify the factors that make organisations more resilient.

Resilience, seen as the capacity for people, organisations, and countries to adapt quickly to new environments has been presented with different perspectives. The most common being the following: (a) Disaster Resilience (e.g. Klein et al., 2004; Manyena, 2006; Gallopin, 2006; Alexander, 2013; Davoudi et al., 2012; IOM (Institute of Medicine), 2015); (b) Infrastructure Resilience (e.g. Omer et al., 2009; Jackson & Ferris, 2013; Chang et al., 2014); (c) Social and Community Resilience (e.g. Tobin, 1999; Pelling & High, 2005; Cutter et al., 2008; Norris et al., 2008; ARUP, 2014; Ross, 2013); (d) Ecological resilience (e.g. Folke, 2006; Curtin & Parker, 2014; Pickett et al., 2014); (e) Economic Resilience (e.g. Rose, 1999; Hallegatte, 2014); (f) Psychological Resilience (e.g. Bonanno, 2004; Campbell-Sills et al., 2009; Mclarnon & Rothstein, 2013); (g) Organisational Resilience (e.g. Coutu, 2002; Hamel & Välikangas, 2003; Cameron et al., 2005; Bhamra et al., 2011; Demmer et al., 2011; Välikangas & Romme, 2013; Stark, 2014; Weick, 2015).

“The ability of a system, community or society to pursue its social, ecological and economic development objectives, while managing its disaster risk over time in a mutually reinforcing way” (Keating et al., 2017).

Infrastructure resilience is the ability to withstand, adapt to changing conditions, and recover positively from shocks and stresses. Resilient infrastructure will therefore be able to continue to provide essential services due to its ability to withstand, adapt and recover positively from whatever shocks and stresses it may face now and in the future (The Resilient Shift, n.d.).

Community resilience can be defined as the absence of illness, as the opposite of vulnerability, as a static and unchanging element, or in a circular way as both a cause and an outcome (Ntontis et al., 2019).

Social-ecological resilience generally is the capacity to continue functioning despite stresses or shocks (Ifejika Speranza et al., 2018).

Economic resilience is described by The National Association of Counties (NACO) as a “community’s ability to foresee, adapt to, and leverage changing conditions to their advantage” (Georgia Tech, n.d.). Economic resilience is usually measured in local or regional dimensions. Regional economic resilience can be described as the ability of a state’s regions to cope with changes in the nature of shocks and disruptions, regardless of their nature (economic, disasters, environment, health), and to use these events to continue their development (Oprea et al., 2020).

Psychological resilience is defined by Sisto et al. (2019) as the ability to maintain the persistence of one’s orientation towards existential purposes. It constitutes a transversal attitude that can be understood as the ability to overcome the difficulties experienced in the different areas of one’s life with perseverance and a good awareness of oneself and one’s own internal coherence by activating a personal growth project.

To Ingram and Głód (2018), organisational resilience is an ambidextrous dynamic capability that allows the firm to take competitive advantage by rapidly and efficiently coping with adversity.

Furthermore, Ortiz-de-Mandojana and Bansal (2015) treat organisational resilience as the firms’ ability to anticipate, avoid, and adjust to cope positively with surprising situations and continuously improve the firms’ viability.

Bearing in mind that organisations are made up of people with common goals, it is underlying that the resilience of organisations depends on the resilience of the people that constitute them and, therefore, the management of intellectual capital and each of its components (namely human capital, capital structural and relational capital) will come up with a possible correlation with the capacity for organisational resilience.

This chapter focuses on the relationship between relational capital and organisational resilience, which is a very broad concept, including strategy, adaptation, culture, risk, and learning organisation. The richness of this concept and its importance have led the authors to develop composite indicators or other frameworks to assess organisational resilience. There has also been specialisation in different areas, sectors, phases of the production process, steps of management, etc. (e.g. specialisation in SMEs, in supply chains and value chains, in the workplace, in the analysis of professions).

As demonstrated, the literature presents a diversity of studies related to the issue of resilience that reflects the lack of consensus that persists today in defining the concept.

The concepts presented below focus on organisational resilience and result from a systematic review of the literature whose main objective is to understand how organisational resilience relates to relational capital.

Organisational Resilience

According to Hillmann and Guenther (2020), organisational resilience can be defined as a capacity, competence, characteristic, result, process, behaviour, strategy, type of performance, or combination.

In contrast, multiple authors criticise the idea that capacity and competence are synonymous. The resilience literature, however, is unclear about what it means to have resilience and resilience competence. These concepts are often used interchangeably. Lengnick-Hall et al. (2011) specify that having a resilience capacity is not equal to having a resilience competence. Richtnér and Löfsten (2014) elaborate that having a capacity means having both the skill and competence. When resilience competence is transformed into action, resilience becomes an organisational capacity (Hillmann & Guenther, 2020).

For Hillmann and Guenther (2020), organisations will only be able to increase their resilience if there is clarity in the concept and the variables that determine it to evaluate, develop, and improve continuously over time.

According to the British Standard 65,000, organisational resilience is defined as “the ability of an organisation to anticipate, prepare for, respond and adapt to incremental change and sudden disruptions in order to survive and prosper.” (Denyer, 2017). Here, the words “and thrive” really matter. Organisational resilience goes beyond survival towards a more holistic view of health and business success. A resilient organisation is Darwinian in the sense that it adapts to a changing environment to remain fit for its purpose (Kerr, 2015).

Another definition presents organisational resilience as a continuous process of benchmarking, improvement and reassessment. It is an organisation’s ability to anticipate, prepare, respond, and adapt to incremental changes and sudden disruptions to survive and thrive (The British Standards Institution, 2018).

Kahn et al. (2018) are based on the definition of Sutcliffe and Vogus (2003) and claim that organisational resilience can also be defined as the organisation’s ability to absorb tension and preserve or improve its functioning, despite the presence of adversity.

Over the years, several articles have been published on how and why companies should develop a strategy to build their organisational resilience to protect themselves from the growing threats to the business. However, organisational resilience is based on a much broader view of resilience as an enabling factor for organisations, allowing them to perform robustly in the long term (Kerr, 2015).

In 2017, the International Organisation for Standardisation published a new standard that provides guidance for increasing the organisational resilience of organisations of any type or dimension, which is not specific to any industry or sector and can be applied throughout the life of an organisation. This international standard 22316 (International Standards Office, 2017) defines organisational resilience as: “the ability of an organisation to absorb and adapt in a changing environment.” It results from a long development process and represents the global consensus on the concept of organisational resilience (BCI, 2017).

ISO 22316: 2017 does not promote uniformity in organisations’ approach. As these are distinct, the specific objectives and initiatives are adapted to meet the particular needs of each organisation (BCI, 2017).

Indicators of Organisational Resilience

According to the literature, the six main indicators of resilience were identified:

The Strategy. Organisational resilience is not a defensive strategy but a positive and forward-looking “strategic enabler” that allows CEOs to take risks measured with confidence. Robust and resilient organisations are flexible and proactive—seeing, anticipating, creating, and taking advantage of new opportunities—to ultimately stand the test of time (Kerr, 2015).

An organisation’s resilience can be a confidence indicator that benefits the company’s reputation, facilitates external investors’ decision, and supports the organisation’s values (Kerr, 2015).

The Culture. Organisational resilience encompasses, but also transcends, the operational aspects of a company. It is based on an organisation’s values, behaviours, culture, and ethos. It is the leaders of an organisation, especially CEOs, who drive these factors, but to make a real cultural difference, the message must circulate from top to bottom and bottom to top. It is also a condition of success, and it is even a mandatory requirement that all employees of the organisation are willing to integrate the message voluntarily (Kerr, 2015).

The Organisational Learning. The writer and philosopher Aldous Huxley said: “Experience is not what happens to a man; it is what a man does with what happens to him.” Likewise, resilience is not what happens with an organisation; it is what the organisation does with what happens to it (Kerr, 2015).

The most resilient organisations are eager to learn from their own experience and that of other organisations to minimise problems, seize opportunities, seek to invest in new areas, introduce innovative products and processes, or penetrate new and unknown markets (Kerr, 2015).

A resilient organisation is adaptable, agile, robust, and competitive, taking advantage of experience and embracing the opportunity to pass the test of time (Kerr, 2015).

Organisational resilience implies adopting best practices—incorporating competence and capacity in all aspects of the organisation—to provide continuous business improvement (Kerr, 2015).

The Dynamism and Statism. Organisational resilience can be divided into dynamic resilience and static resilience (Annarelli and Nonino, 2016). Dynamic resilience is based on dynamic resources that allow organisations to manage unexpected threats and risks, while static resilience deals with strategic resilience initiatives based on the management of internal and external resources (Annarelli & Nonino, 2016; Jia, 2018).

Amore et al. (2018) also argue that static resilience and dynamic resilience coexist with the views of proactive resilience and reactive resilience. According to Somers (2009), reactive resilience refers to the organisation’s ability to return to its normal state without incurring serious damage or loss, while proactive resilience refers to deliberate efforts that increase the ability to deal with threats potential (Jia, 2018; Lovins & Lovins, 1982).

Leadership. The literature on leadership and its outcomes can be studied from different perspectives (Asrar-ul-Haq & Anwar, 2018). Frequently, the definition of leadership is related to the trait, ability, skill, behaviour, and relationship that shows that the leadership field of study rushed from one fad to another (Yukl, 2013). The impact of leadership on business and organisational management has been recognised as a significant factor that could make a difference in organisational performance (Al Amiri et al., 2020).

Harland et al. (2005) theorised on a link between leadership and resilience. These authors stated that developing the capacity for resilience is a vital component of effective leadership. Wan Sulaiman et al. (2012) found significant correlations between leadership and resilience, namely the higher the skills of leadership, the higher the ability to be resilient and to overcome challenges.

According to British Standards Institution (ISO, 2017), leadership is perceived as both important and relative strength in terms of resilience. Strong leaders promote subordinates’ intrinsic motivation, show concern for their needs, focus on emotional aspects, care about employee needs, provide social support and furnish work support to broaden their individual responsibilities for assuming greater challenges. Therefore, strong leadership enhances work engagement (Tau et al., 2018).

Furthermore, highly resilient individuals cope more successfully with stress and negative events and therefore have high levels of positive affect, and employees/individuals with high positive affect are more inclined to be engaged with their work (Wang et al., 2017).

Research has shown that leaders need to be resilient in order to lead their teams. According to Jackson and Daly (2011), resilient leaders not only have the ability to survive in difficulty and adversity but are able to display behaviour that will enhance subordinates’ ability to thrive. In consequence, it is clear that higher leadership qualities are related to higher resilience levels. In fact, Moran and Tame (2012) confirmed that for organisations to adapt, individuals must work towards a resilient culture.

Adaptive Capacity. Several authors argue that adaptive capacity is a significant factor in characterising vulnerability and may be defined as “the extent to which a system can modify its circumstances to move to a less vulnerable condition” (Dalziell & Mcmanus, 2008; Luers et al., 2003).

Adaptive capacity reflects the ability of the system to respond to changes in its external environment and recover from damage to internal structures within the system that affect its ability to achieve its purpose (Dalziell & Mcmanus, 2008). Recovery is closely linked to the time taken by the organisation to intervene, i.e. whether the organisation intervened pre-event or post-event. Thus, it is essential to characterise two types of resilience: proactive resilience or reactive resilience.

Proactive organisational resilience identifies potential risks and takes proactive steps to ensure an organisation will survive and thrive in an adverse situation in the future (Longstaff, 2005; Somers, 2009).

According to Lengnick-Hall et al. (2011), reactive organisational resilience is the capability to effectively and efficiently respond to external disruptions and quickly recover to an organisation’s pre-impact state after experiencing extreme external impacts. In addition, reactive organisational resilience is closely related to operational losses and time of reaction and recovery (Bruneau & Reinhorn, 2007).

As Jia et al. (2020) noted, time of reaction and recovery refers to the required time for initial reactions to disruptions based on their business continuity plan and restoration of disrupted functions through their recovery plans.

4 Relationship Between Relational Capital and Organisational Resilience: A Conceptual Framework

For Johnson et al. (2013), factors of the CR, such as trust and cooperation, promote the construction of information sharing structures in companies established in networks, thus emphasising the importance of formal and informal network ties. The research confirms that these factors are valuable resources and contribute to the training capacities of organisational resilience.

Polyviou et al. (2019), when analysing the resources that allow small and medium-sized companies to become resilient, concluded that the relationships established between employees and/or groups within a network create cohesion and facilitate the search for collective goals, being beneficial for companies, as it facilitates the acquisition of tacit knowledge and access to resources for the exchange of knowledge and collaboration. Thus, it is concluded that these organisational relationships develop resources that enhance resilience capacities, mitigating risks or helping organisations to recover from periods of crisis.

The research by Yoo et al. (2016) complements that the RC generates close interaction between alliance partners and provides an effective channel for organisational learning, for accumulation and sharing knowledge, creating a better performance for the companies and their strategic alliance partners. Consequently, the companies inserted in a dynamic and volatile environment, which have a strong Relational Capital structure, can contribute to the achievement of more fruitful organisational results, directing efforts to expand the resilient capacities of organisations.

Walecka’s research (2021) confirms that the high level of RC contributes to building resilience. The research identified in companies from different sectors, that factors such as long-term cooperation, trust between groups and stakeholders, and the relationships established with stakeholders, namely, the indicators that form the well-developed relational capital of a company allow not only protecting the company against the crisis but also overcoming it, developing resilient capacities. These findings contribute to the proposal of this research.

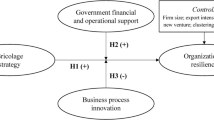

In consequence, it is relevant to broaden the understanding of the CR through the frequency and quality of the relations established by the company with its stakeholders, by the strategies and benefits of long-term cooperation between companies with their customers and suppliers and by the intensity and frequency of collaboration for achieving common goals; for the trust established with the interested groups, and for the frequency of communication established with the stakeholders to share information and knowledge about the sector. These factors of organisational resilience allow companies to benefit from the knowledge base available in interorganisational relationships, which stimulates the development of capacities, such as adaptive capacity, organisational learning, leadership, the culture of sharing (Fig. 4.1).

The conceptual model above shows that the indicators of the development of relational capital are complementary and jointly contribute to organisational resilience. Likewise, resilience indicators, acting together, provide organisations with adaptive capacities that make them more agile and resilient. Although the conceptual framework tries to give an image of the indicators independently, this independence does not exist. The imbalance between indicators inevitably affects the capacity for resilience (e.g. between culture and leadership or between trust and communication).

On the other hand, the results of this research indicate that resilience and relational capital influence each other. This means that, predictably, there is a relationship between resilience and relational capital, as specified in the objective of this research. Demonstrating this relationship, in empirical terms, is, therefore, one of the challenges of future research.

5 Conclusion and Future Work

This exploratory research sought to identify the CR factors that enhance the capacity for organisational resilience and the link between relational capital and organisational resilience, using a literature review.

The results of this paper corroborate the understanding that a high level of RC enables organisations to face turbulent periods and crises in companies and to strengthen organisational resilience capacities. Factors such as relationships, cooperation, collaboration, trust, and communication, which organisations build with their stakeholders, were identified as essential for the RC to develop.

The relationship established between the resilience indicators, namely the type of strategy, the organisational culture, the organisational learning, the leadership, the dynamism and statism balance and the adaptive capacity, also emerged as conditioning indicators of the resilience capacity. The theoretical discussion of the association of the relational capital and resilience binomial is a contribution to the literature and supports the evidence that the two topics influence each other and contribute to reinforce organisational resilience.

Additionally. the results of this study provide theoretical implications that allow advances in research regarding the topics of Relational Capital and Resilience, allowing to fill in the gaps that highlight the antecedent factors of these constructs. The understanding and familiarity with these factors of organisational resilience are particularly relevant for managers of companies operating in an emerging economy and in a dynamic, complex and high technological mobility environment, who exploit the intangible resources of the RC as a strategy to mitigate crises.

The limitations of this study drive future research that can use the other dimensions of the IC, such as structural capital and human capital, as measures to analyse the resilience capacity.

References

Al Amiri, N., Rahim, R. E. A., & Ahmed, G. (2020). Leadership styles and organisational knowledge management activities: A systematic review. Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 22(3), 250–275. https://doi.org/10.22146/gamaijb.49903

Alexander, D. E. (2013). Resilience and disaster risk reduction: An etymological journey (pp. 1257–1284). doi:https://doi.org/10.5194/nhessd-1-1257-2013.

Amore, A., Prayag, G., & Hall, C. (2018). Conceptualising destination resilience from a multilevel perspective. Tourism Review International, 22, 235–250. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427218X15369305779010

Andreeva, T., & Garanina, T. (2016). Do all elements of intellectual capital matter for organisational performance? Evidence from Russian context. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 17(2), 397–412. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-07-2015-0062

Annarelli, A., & Nonino, F. (2016). Strategic and operational management of organisational resilience: Current state of research and future directions. In Omega (United Kingdom) (Vol. 62, pp. 1–18). Elsevier Ltd. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2015.08.004.

ARUP. (2014). Understanding the city resilience index. Accessed April 14, 2021, from https://www.arup.com/projects/city-resilience-index

Asrar-ul-Haq, M., & Anwar, S. (2018). The many faces of leadership: Proposing research agenda through a review of literature. Future Business Journal, 4(2), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbj.2018.06.002

BCI. (2017). Accessed March 13, 2021. Avaliable at: https://www.thebci.org/news/iso-publishes-22316-2017-security-and-resilienceorganizational-resilience-principles-and-attributes.html

Bhamra, R., Dani, S., & Burnard, K. (2011). Resilience: The concept, a literature review and future directions. International Journal of Production Research, 49(18), 5375–5393. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2011.563826

Bolisani, E., & Bratianu, C. (2017). Knowledge strategy planning: an integrated approach to manage uncertainty, turbulence, and dynamics. Journal of Knowledge Management, 21(2), 233–253. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-02-2016-0071

Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

Bontis, N. (1996). There’ a price on on your head: Managing intellectual capital strategically. Business Quarterly, 60(4).

Brooking, A. (1996). Intellectual capital: Core assets for the third millenium enterprise. International Thompson Business Press. Accessed March 20, 2021, from https://books.google.pt/books?id=trzBnQAACAAJ

Bruneau, M., & Reinhorn, A. (2007). Exploring the concept of seismic resilience for acute care facilities. Earthquake Spectra, 23(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1193/1.2431396

Buenechea-Elberdin, M., Kianto, A., & Sáenz, J. (2018). Intellectual capital drivers of product and managerial innovation in high-tech and low-tech firms. R and D Management, 48(3), 290–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12271

Cameron, K., Lim, S., & Gittell, J. H. (2005). Resilience: Airline industry responses to organisational resilience. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 2015, 1–41.

Campbell-Sills, L., Forde, D., & Stein, M. (2009). Demographic and childhood environmental predictors of resilience in a community sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43, 1007–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.01.013

Capello, R., & Faggian, A. (2005). Collective learning and relational capital in local innovation processes. Regional Studies, 39(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320851

Chang, S. E., Mcdaniels, T., Fox, J., Dhariwal, R., & Longstaff, H. (2014). Toward disaster-resilient cities: Characterizing resilience of infrastructure systems with expert judgments. Risk Analysis, 34(3), 416–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12133

Coutu, D. L. (2002). How resilience works. In Harvard Business Review (Vol. 80, Issue 5, p. 46). Accessed March 13, 2021, from https://hbr.org/2002/05/how-resilience-works

Creswell, J. W. (2010). Creswell, J.W. projeto de pesquisa- método qualitativo, quantitativo e misto. Tradução de Luciana de oliveira da rocha. 2 Ed. Porto Alegre-artmed, 2007. Artmed. Accessed March 12, 2021, from http://ir.obihiro.ac.jp/dspace/handle/10322/3933

Curtin, C., & Parker, J. (2014). Foundations of resilience thinking. Conservation Biology, 28, 912–923. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12321

Cutter, S. L., Barnes, L., Berry, M., Burton, C., Evans, E., Tate, E., & Webb, J. (2008). A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Global Environmental Change, 18, 598–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.07.013

Dalziell, E. P., & Mcmanus, S. T. (2008). Resilience, vulnerability, and adaptive capacity: Implications for system performance. Accessed April 13, 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/2948937

Davoudi, S., Shaw, K., Haider, L. J., Quinlan, A. E., Peterson, G. D., Wilkinson, C., Fünfgeld, H., McEvoy, D., & Porter, L. (2012). Resilience: a bridging concept or a dead end? “Reframing” resilience: challenges for planning theory and practice interacting traps: Resilience assessment of a pasture management system in northern afghanistan urban resilience: What does it mean in planni. Planning Theory and Practice, 13(2), 299–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677124

Demmer, W., Vickery, S., & Calantone, R. (2011). Engendering resilience in small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): A case study of Demmer Corporation. International Journal of Production Research, 49, 5395–5413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2011.563903

Denyer, D. (2017). Organisational Resilience: A summary of academic evidence, business insights and new thinking. BSI and Cranfield School of Management, UK. Accessed April 19, 2021, from https://www.cranfield.ac.uk/~/media/images-for-new-website/som-media-room/images/organisational-report-david-denyer.ashx

Edvinsson, L. (1997). Developing intellectual capital at Skandia. Long Range Planning, 30(3), 366–373.

Edvinsson, L. (2002). Corporate longitude. Pearson Education.

Edvinsson, L. (2013). IC 21: Reflections from 21 years of IC practice and theory. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 14(1), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691931311289075

Edvinsson, L., & Malone, M. (1997). Intellectual capital – Realising your company’s true value by finding its hidden brainpower. Harper Business.

Engelman, R., Schmidt, S., & Fracasso, E. M. (2016). Capital intelectual: Adaptação e validação de uma escala para o contexto Brasileiro. Espacios, 37(36).

Folke, C. (2006). Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for socio-ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change, 16, 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.04.002

Gallopin, G. C. (2006). Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. July. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.02.004.

García, A. B., & Bounfour, A. (2014). Knowledge asset similarity and business relational capital gains: Evidence from European manufacturing firms. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 12(3), 246–260. https://doi.org/10.1057/kmrp.2014.2

Georgia Tech. (n.d.). What is economic resilience? – Center for Economic Development Research. Retrieved April 19, 2021, from https://cedr.gatech.edu/what-is-economic-resilience/. Accessed April 18, 2021.

Hallegatte, S. (2014). Economic resilience: Definition and measurement. May.

Hamel, G., & Välikangas, L. (2003, September). The quest for resilience. Accessed 18 April 2021, from https://hbr.org/2003/09/the-quest-for-resilience

Harland, L., Harrison, W., Jones, J. R., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2005). Leadership behaviors and subordinate resilience. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 11(2), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190501100202

Hillmann, J., & Guenther, E. (2020). Organisational resilience: A valuable construct for management research? International Journal of Management Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12239

Ho, M. H.-W., Ghauri, P. N., & Kafouros, M. (2019). Knowledge acquisition in international strategic alliances: The role of knowledge ambiguity. Management International Review, 59(3), 439–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-019-00383-w

Ifejika Speranza, C., Ochege, F. U., Nzeadibe, T. C., & Agwu, A. E. (2018). Agricultural resilience to climate change in Anambra State, Southeastern Nigeria: Insights from public policy and practice. In Beyond agricultural impacts: Multiple perspectives on climate change and agriculture in Africa (pp. 241–274). Elsevier. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812624-0.00012-0.

Ingram, T., & Głód, G. (2018). Organisational resilience of family business: Case study. Ekonomia i Prawo, 17(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.12775/eip.2018.005

International Standards Office. (2017). ISO 22316:2017 – Security and resilience – Organisational resilience – Principles and attributes. Accessed April 19, 2021, from https://www.iso.org/standard/50053.html

IOM (Institute of Medicine). (2015). Healthy, resilient, and sustainable communities after disasters: A discussion toolkit.

Jackson, D., & Daly, J. (2011). All things to all people: Adversity and resilience in leadership. Nurse Leader, 9(3), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2011.03.003

Jackson, S., & Ferris, T. L. J. (2013). Resilience principles for engineered systems. October 2017. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sys.21228. Accessed April 20, 2021.

Jia, X. (2018). The role of social capital in building organizational resilience, 136.

Jia, X., Chowdhury, M., Prayag, G., & Hossan Chowdhury, M. M. (2020). The role of social capital on proactive and reactive resilience of organisations post-disaster. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101614

Johnson, N., Elliott, D., & Drake, P. (2013). Exploring the role of social capital in facilitating supply chain resilience. Supply Chain Management, 18(3), 324–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/SCM-06-2012-0203

Kahn, W. A., Barton, M. A., Fisher, C. M., Heaphy, E. D., Reid, E. M., & Rouse, E. D. (2018). The geography of strain: Organisational resilience as a function of intergroup relations. Academy of Management Review, 43(3), 509–529. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0004

Keating, A., Campbell, K., Mechler, R., Magnuszewski, P., Mochizuki, J., Liu, W., Szoenyi, M., & McQuistan, C. (2017). Disaster resilience: What it is and how it can engender a meaningful change in development policy. Development Policy Review, 35(1), 65–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.12201

Kerr, H. (2015). Organisational resilience: Harnessing experience, embracing opportunity (pp. 129–147). British Standards Institution.

Keszey, T. (2018). Boundary spanners’ knowledge sharing for innovation success in turbulent times. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(5), 1061–1081. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-01-2017-0033

Klein, R. J. T., Nicholls, R. J., & Thomalla, F. (2004). Resilience to natural hazards. How useful is this concept?, 5(2003), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hazards.2004.02.001

Knight, D. J. (1999). Performance measures for increasing intellectual capital. Strategy and Leadership, 27(2), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb054632

Lengnick-Hall, C. A., Beck, T. E., & Lengnick-Hall, M. L. (2011). Developing a capacity for organisational resilience through strategic human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 21(3), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.07.001

Liu, C. L. E., Ghauri, P. N., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2010). Understanding the impact of relational capital and organisational learning on alliance outcomes. Journal of World Business, 45(3), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2009.09.005

Longstaff, P. H. (2005). Security, resilience, and communication in unpredictable environments such as terrorism, natural disasters, and complex technology. Center for Information Policy Research, Harvard University (Issue September).

Lovins, A. B., & Lovins, L. H. (1982). Brittle power: Energy strategy for national security. Foreign Affairs, 61(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/20041378.

Lu, Y. K., & Wang, E. T. G. (2012). Inter-firm cooperation and IOS deployments in buyer-supplier relationships: A relational view. ECIS 2012 - Proceedings of the 20th European Conference on Information Systems.

Luers, A. L., Lobell, D. B., Sklar, L. S., Addams, C. L., & Matson, P. A. (2003). A method for quantifying vulnerability, applied to the agricultural system of the Yaqui Valley, Mexico. Global Environmental Change, 13(4), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(03)00054-2

Manyena, B. (2006). The concept of resilience revisited. Disasters, 30, 434–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0361-3666.2006.00331.x

Mariano, S. (2021). Let me help you! Navigating through the COVID-19 crisis with prosocial expert knowledge behaviour. Knowledge Management Research and Practice, 00(00), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2020.1866445

Matos, F., Vairinhos, V., & Godina, R. (2020). Reporting of intellectual capital management using a scoring model. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(19), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198086

Mclarnon, M., & Rothstein, M. (2013). Development and initial validation of the workplace resilience inventory. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 12, 63. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000084

Moran, B., & Tame, P. (2012). Organisational resilience: Uniting leadership and enhancing sustainability. Sustainability: The Journal of Record, 5, 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1089/SUS.2012.9945

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6

Ntontis, E., Drury, J., Amlôt, R., Rubin, G. J., & Williams, R. (2019). Community resilience and flooding in UK guidance: A critical review of concepts, definitions, and their implications. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 27(1), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12223

Omer, M., Nilchiani, R., & Mostashari, A. (2009). Measuring the resilience of the transoceanic telecommunication cable system. IEEE Systems Journal - IEEE SYST J, 3, 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSYST.2009.2022570

Oprea, F., Onofrei, M., Lupu, D., Vintila, G., & Paraschiv, G. (2020). The determinants of economic resilience. The case of Eastern European regions. Sustainability (Switzerland), 12(10), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104228

Ordóñez de Pablos, P., & Edvinsson, L. (Eds.). (2020). Intellectual capital in the digital economy (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429285882

Ortiz-de-Mandojana, N., & Bansal, T. (2015). The long-term benefits of organisational resilience through sustainable business practices. Strategic Management Journal, 37. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2410

Osinski, M., Selig, P., Matos, F., & Roman, D. (2017). Methods of evaluation of intangible assets and intellectual capital. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 18. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-12-2016-0138

Pelling, M., & High, C. (2005). Understanding adaptation: What can social capital offer assessments of adaptive capacity? Global Environmental Change, 15(4), 308–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2005.02.001

Pickett, S. T. A., McGrath, B., Cadenasso, M. L., & Felson, A. J. (2014). Ecological resilience and resilient cities. Building Research and Information, 42(2), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2014.850600

Polyviou, M., Croxton, K., & Knemeyer, A. (2019). Resilience of medium-sized firms to supply chain disruptions: the role of internal social capital. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 40. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-09-2017-0530

Richtnér, A., & Löfsten, H. (2014). Managing in turbulence: How the capacity for resilience influences creativity. R and D Management, 44(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12050

Rodrigues, H. M. da S. S., Dorrego, P. F. F., & Fernández, C. M. F.-J. (2009). La Influencia Del Capital Intelectual En La Capacidad de Innovación de Las Empresas Del Sector de Automoción de La Eurorregión Galicia Norte De Portugal. Universidad de Vigo de Vigo, May 2014. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84871106928&partnerID=tZOtx3y1

Roos, G., & Roos, J. (1997). Measuring your company’s intellectual performance. Long Range Planning, 30(3), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0024-6301(97)90260-0

Rose, A. (1999). Defining and measuring economic resilience to earthquakes (pp. 41–54).

Ross, A. D. (2013). Local disaster resilience: Administrative and political perspectives. In Local disaster resilience: Administrative and political perspectives. Taylor and Francis. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203551912.

Sisto, A., Vicinanza, F., Campanozzi, L. L., Ricci, G., Tartaglini, D., & Tambone, V. (2019). Towards a transversal definition of psychological resilience: A literature review. Medicina (Lithuania) (Vol. 55, Issue 11). MDPI AG. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55110745.

Sneader, K., & Singhal, S. (2020). The future is not what next normal on the shape of the it used to be: Thoughts. McKinsey & Company, 372(9645), 1222. Accessed April 8, 2021, from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/leadership/the-future-is-not-what-it-used-to-be-thoughts-on-the-shape-of-the-next-normal

Somers, S. (2009). Measuring resilience potential: An adaptive strategy for organizational crisis planning. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5973.2009.00558.x

Stark, A. (2014). Bureaucratic values and resilience: An exploration of crisis management adaptation. Public Administration, 92. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12085

Stewart. (1998). Intellectual capital: The new wealth of organisation. International Journal of Manpower, 21, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr.2000.29.1.115.1

Sutcliffe, K. M., & Vogus, T. J. (2003). Organising for resilience. Positive Organisational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline, October, 94–110.

Sveiby, K. E. (1998). A nova riqueza das organizações: Gerenciando e avaliando patrimônios de conhecimento (Vol. 11).

Tau, B., Du Plessis, E., Koen, D., & Ellis, S. (2018). The relationship between resilience and empowering leader behaviour of nurse managers in the mining healthcare sector. Curationis, 41(1), e1–e10. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v41i1.1775

Teo, W. L., Lee, M., & Lim, W. S. (2017). The relational activation of resilience model: How leadership activates resilience in an organisational crisis. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 25(3), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12179

The British Standards Institution. (2018). Organizational resilience index contents (pp. 1–28). Accessed April 10, 2021, from https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/our-services/Organizational-Resilience/Organizational-Resilience-Index/thank-you-ga-03ri/

The Resilient Shift. (n.d.). What is critical infrastructure? Why is resilience important? https://www.resilienceshift.org/work-with-us/faqs/ Accessed April 19, 2021.

Tobin, G. A. (1999). Sustainability and community resilience: The holy grail of hazards planning? Environmental Hazards, 1(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.3763/ehaz.1999.0103

Välikangas, L., & Romme, G. (2013). How to design for strategic resilience: A case study in retailing. Journal of Organization Design, 2(2), 44. https://doi.org/10.7146/jod.7360

Venugopalan, M., Sisodia, G., & Rajeevkumar, P. (2018). Business relational capital and firm performance: An insight from Indian textile industry. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 15, 341. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLIC.2018.095899

Verhoef, P. C., Broekhuizen, T., Bart, Y., Bhattacharya, A., Qi Dong, J., Fabian, N., & Haenlein, M. (2021). Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 122(July 2018), 889–901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.022

Walecka, A. (2021). The role of relational capital in anti-crisis measures undertaken by companies—conclusions from a case study. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020780

Wan Sulaiman, W. S., Ibrahim, F., N., A., & B., I. (2012). A cooperative study of self-esteem, leadership and resilience amongst illegal motorbike racers and normal adolescents in Malaysia. Asian Social Science, 8. doi:https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v8n8p61.

Wang, Z., Li, C., & Li, X. (2017). Resilience, leadership and work engagement: The mediating role of positive affect. Social Indicators Research, 132(2), 699–708. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1306-5

Warkentin, M., Scuotto, V., & Edvinsson, L. (2021). Guest editorial. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 22(3), 433–438. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-05-2021-389

Weick, K. (2015). Ambiguity as Grasp: The reworking of sense. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12080

Welbourne, T., & Pardo-del-Val, M. (2008). Relational capital: Strategic advantage for small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) through negotiation and collaboration. Group Decision and Negotiation, 18, 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-008-9138-6

Yoo, S.-J., Sawyerr, O., & Tan, W.-L. (2016). The mediating effect of absorptive capacity and relational capital in alliance learning of SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 54, 234–255.

Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in organisations (8th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Matos, F., Tonial, G., Monteiro, M., Selig, P.M., Edvinsson, L. (2022). Relational Capital and Organisational Resilience. In: Matos, F., Selig, P.M., Henriqson, E. (eds) Resilience in a Digital Age. Contributions to Management Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85954-1_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85954-1_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-85953-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-85954-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)