Abstract

In this chapter, the authors critically review the body of research on adolescents’ and emerging adults’ pornography use and its consequences. We start with a number of theoretical concepts—including social learning and comparison theories, sexual scripting, self-objectification theory, the confluence model, the value congruence model, cultivation and media practice models developed in communication science, and the differential susceptibility to media model—that have been employed in the field, mainly with the goal of understanding possible effects of youth pornography use. Next, we explore the prevalence (both pre- and post-internet), the dynamics (i.e., change over time), and correlates of pornography exposure and use. Associations between pornography use on the one hand and sexual risk taking and sexual aggression on the other hand are explored in separate sections. The role of pornography use in young people’s psychological and sexual well-being is also explored, focusing on possible negative, but also positive outcomes. Acknowledging rising societal concerns, we also reviewed the research on the role of parents in their children’s experience with pornography, as well as the potential contribution of emerging pornography literacy programs. In the final section, we present some recommendations for future research. In particular, much needed measurement (for pornography use and its specific content) and research design improvements are suggested, and practical implications are briefly discussed.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Pornography use

- Adolescents and emerging adults

- Sexual risk taking

- Sexual aggression

- Psychological and sexual well-being

In 1995, at the beginning of a period of near-exponential growth in Internet pornography, Philip Elmer-Dewitt shocked many parents with his Time cover story about “Cyberporn.” The cover line salaciously promised to reveal how “wild” Internet pornography had become, and explicitly framed the pornography debate around the balance between protecting free speech and protecting children (Elmer-Dewitt, 1995). The story described soon to be discredited research that claimed that growth in online pornography was primarily driven by pedophilic and hebephilic interests (see Rimm, 1995). Upon release, both Rimm’s study and Elmer-Dewitt’s story were lambasted—with the Time article eventually becoming required reading in ethics of journalism classes as a case study in what not to do (Elmer-Dewitt, 2015). Despite criticism by many journalists and scholars, both pieces resonated with deep-seated fears among many Americans surrounding sexuality and children (Levine, 2006), which ultimately coalesced into the Communications Decency Act, the first attempt by the U.S. Congress to regulate Internet pornography.

Concern about pornography and children is not new, as George Putnam asserted back in 1965, “[a] flood-tide of filth…” always seems poised “…to pervert an entire generation of our American children” (Citizens for Decent Literature, 1965). However, as Elmer-Dewitt’s story illustrates, in recent decades, pornography on the Internet seems to have given new urgency to the issue, perhaps because of the assumed, if largely undemonstrated (Byers et al., 2004), increase in anonymity, affordability, and accessibility that the Internet provides (Cooper et al., 2000, 2004). This Internet-fueled panic about pornography has likely motivated the recent surge in academic interest in adolescent pornography use over the last two decades.

The clear focus on adolescents in recent years is unsurprising given the pervasive concern among academics that adolescents are uniquely vulnerable to the effects of pornography exposure (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013), presumably because of underdeveloped inhibitory-control systems in the pre-frontal cortex (Owens et al., 2012). Although this is a reasonable supposition to propose, and it may very well be true, it has yet to be demonstrated empirically that adolescents are uniquely vulnerable to the effects of pornography. At the same time, this perspective is also more than a little reminiscent of the long-standing paternalistic Western tradition of regulating access to sexual materials so that those with poor “moral fortitude”—namely, women, children, and the less educated—would not be corrupted by its influence (Kendrick, 1987).

The generally assumed vulnerability of adolescents has manifested in specific concerns about pornography’s impact on sexual risk taking, sexual aggression, and well-being among young people (Collins et al., 2017; Owens et al., 2012; Peter & Valkenburg, 2016; Pizzol et al., 2016). In recent years, concern about pornography has also driven the development of porn literacy programs as well as other interventions designed to reduce its presumed harms (Rothman et al., 2018). This review seeks to provide a critical examination and summary of this literature. It will begin by providing an overview of relevant theory in this area followed by a description of research concerning adolescent pornography use. Next, the research regarding pornography’s impact on adolescent sexual risk taking, sexual aggression, and well-being will be discussed. After describing emerging insights from efforts to improve porn literacy and briefly discussing the role of parents for mitigating harms associated with pornography use, the review will conclude with recommendations for future research in this area.

Before we begin, we wish to clarify what we mean by “pornography.” The meaning of this term has a rather confusing history among academics, as various, and often conflicting, definitions have been proposed by a number of scholars. This state of affairs has led some researchers to claim that pornography is such an idiosyncratic concept that developing a universally agreed upon definition may be a futile effort (Manning, 2006). Others have tried to side-step the issue by coining alternative non-pejorative language (e.g., “sexually explicit materials,” “visual sexual stimuli”)(Vaillancourt-Morel et al., 2019). We believe that both of these perspectives are mistaken. Pornography is the most widely used term among both academics and laypersons to refer to sexual representations, and empirical research suggests that individual and cultural differences in its meaning are relatively trivial. Employing diverse terminology unnecessarily fragments the field (for a comprehensive review, see Kohut et al., 2020). In this chapter, we use the term pornography to mean “representations of nudity which may or may not include depictions of sexual behavior” (Kohut et al., 2020).

14.1 Theoretical Approaches to Understanding Young People’s Pornography Use

Four types of theoretical approaches have been used in research involving young people’s pornography use: (1) general social psychological conceptualizations , such as Bandura’s social learning (Peter & Valkenburg, 2011a) and Festinger’s social comparison theories (Wright & Štulhofer, 2019; Peter & Valkenburg, 2014); (2) communication science models of media effects, such as the cultivation (Gerbner, 1998; Morgan & Shanahan, 2010), the media practice (Brown, 2000; Steele, 1999; Steele & Brown, 1995) and the Differential Susceptibility to Media models (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013); (3) feminism-informed objectification and self-objectification theoretical models (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2014a, 2014b), which bridge body image and communication studies focusing mainly on the sexualization of young women; and (4) pornography-specific conceptualizations that seek to explain the specific effects of such materials (Grubbs & Perry, 2018; Valkenburg & Peter, 2013; Vega & Malamuth, 2007; Wright, 2014). Generally speaking, pornography-specific models focus on the role that pornography plays in young people’s sexual socialization, a process that includes sexual identity and role formation, as well as the crystallization of beliefs about the sexual roles of partners, internalization of sexual body ideals and sexual power dynamics, the shaping of views about the relationship between sexuality and emotions, and scripting of specific sexual activities as well as their expected sequences (Štulhofer et al., 2010). From this perspective, it is assumed that ubiquitous online pornography is a powerful agent of sexual socialization that serves as a constant reminder of the social imperative to be sexual, acts as a source of (mis)information about the acceptance of specific sexual acts, and, consequently, generates specific normative expectations (Brown et al., 2005). Such models will be the primary focus of this review.

Originally developed to improve the prediction of sexual aggression (Malamuth et al., 1996), Malamuth’s Confluence Model was later extended to include pornography as a risk factor for sexual aggression (Kingston et al., 2009; Malamuth, 2018). In essence, the model posits that pornography use—especially, but not exclusively, violent sexually explicit content—increases the risk of sexual aggression, but only among men who are predisposed to such behavior (Malamuth et al., 2000). More precisely, individual characteristics, primarily hostile masculinity (a hostile, distrustful and narcissistic need to dominate women) and impersonal sexuality (the callous, unemotional, and promiscuous orientation toward sex), shape both the preference for specific pornographic content and frequent consumption of such materials, as well as the proclivity to sexual aggression (Malamuth & Hald, 2017). Thus, frequent pornography use is expected to increase the risk of sexual aggression among a relatively small subgroup of users high in hostile masculinity and impersonal sex. While this theory has received support in several samples of emerging adults (Malamuth, 2018), and has been referenced in the adolescents literature (Ybarra & Thompson, 2018), the critical interaction between vulnerability factors (e.g., hostile masculinity and impersonal sexuality) and pornography use has yet to be examined in adolescent samples.

Based on the sexual scripting (Simon & Gagnon, 2003) and the cultivation theories, Wright proposed the Acquisition, Activation and Application Model (3AM) of pornography-affected sexual socialization (Wright, 2011, 2014). The model specifies three psychosocial causal mechanisms—acquisition, activation, and application—that underlie, usually in a sequential order, the impact of pornography use on real life sexuality. Briefly, the acquisition phase refers to the process of internalizing pornographic scripts, which is facilitated by sexually explicit, arousing, and attention-grabbing content. In the next phase, the newly acquired scripts can be activated in certain situations, depending, among other things, on script-situation correspondence. Finally, pornographic scripts will be evaluated and applied in a situation if the presumed benefits exceed the costs related to script enactment. According to Wright, a number of factors influence all three phases. For example, gender and age are likely to moderate script acquisition, frequency of pornography use and gender stereotypical attitudes are likely to influence the process of activation, while negative mood may increase the likelihood of the application of risky sexual scripts (Wright, 2011; Wright & Bae, 2016). Whether or not adolescents are especially likely to acquire sexual scripts from pornography remains an empirical question.

Recently, a new conceptual model was presented to account for self-assessed problematic pornography use. The Moral Incongruence model posits that holding negative religious or faith-based evaluations of pornography while simultaneously using pornography can cause significant distress induced by the discrepancy between one’s attitudes and one’s behaviors. This discrepancy is experienced as a perceived lack of control over pornography use, which in turn contributes to self-diagnosed addiction to pornography (Grubbs & Perry, 2018; Grubbs et al., 2019). Such theorizing has distinguished between truly (i.e., objectively) dysregulated use of pornography and perceived (i.e., subjective) out-of-control pornography use due to moral incongruence, and explicitly allows for a possible link between the two (Grubbs et al., 2019). According to meta-analytic findings (the Moral Incongruence hypothesis has received considerable empirical support; see Grubbs & Perry, 2018), the association between moral incongruence and problematic pornography use is markedly stronger than relationships between religiosity and frequency of pornography use on the one hand, and problematic pornography use on the other hand (Grubbs et al., 2019). Although this model emerged from an effort to explain why highly religious young adults experience considerable distress and perceived pornography addiction despite generally low or moderate levels of pornography use, a recent study that used two independent panel samples of male Croatian adolescents did not substantiate these model-based expectations (Kohut & Štulhofer, 2018a).

Finally, although it was not specifically developed to explain possible effects of pornography use, the Differential Susceptibility to Media model (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013), not to be conflated with Belsky’s differential susceptibility hypothesis (Belsky, 1997), will also be briefly mentioned here. We feel that it is important to describe this model because it is an integrative conceptual framework that synthesizes much of the media effects literature, and thus can greatly assist researchers in the field of pornography use. The model attempts to inform answers to the following questions: What makes some individuals more vulnerable to media effects; what are the mechanisms underlying media effects; and how can these effects be modified? Four propositions form the core of the Differential Susceptibility to Media model. First, media effects are conditional on consumers’ (1) dispositional (gender, personality characteristics, and attitudes), developmental (adolescence as a particularly vulnerable period), and social susceptibility (family and peer environments, culture-specific norms and institutions). Secondly, media effects are indirect, mediated by cognitive, emotional, and excitative response states. Thirdly, differential susceptibility predicts the type and frequency of media use, but also moderates the associations between media consumption and response states. Finally, media effects are assumed to be transactional, meaning that there are feedback loops from media-influenced outcomes to differential susceptibility, response states, and future media use (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013). For example, frequent use of online pornography may normalize a specific sexual act (by creating an impression that most people have incorporated it into their sexual repertoire) that the person previously found morally unacceptable. This media-influenced normalization may increase the likelihood of trying the sexual act. Provided it was rewarding, the experience may lead to more exposure to pornographic content that depicts the act and to higher sexual arousal while watching it. Compared to the above-described conceptual models, the Differential Susceptibility Model is obviously an exhaustive and well-structured list of individual-level moderators and mediators to be considered when exploring media effects, rather than a limited set of theoretical expectations to be empirically tested.

While often theoretically informed, research concerning adolescent pornography use rarely evaluates theoretical explanations for the impact of pornography use in a rigorous manner. This is particularly true with respect to theories that specify potential vulnerabilities to the effects of pornography, the study of which has been previously characterized as a “patchwork of haphazardly selected moderators with inconsistent results rather than a systematic research program” (Peter & Valkenburg, 2016). A central component of the hypothetico-deductive scientific method is that theories are tested by subjecting derived predictions to empirical scrutiny (Haig, 2018). If observations accord with the predictions, then the theory is seen as more credible; but, if they do not, then some aspect of the theory may need to be revised. This latter aspect of the scientific method is not prominent when researchers consider the impact of pornography use among adolescents. Instead, theory tends to be used to justify the investigation of a specific phenomenon (e.g., the association between pornography use and sexual risk taking), sometimes by appealing to multiple explanatory mechanisms that can be used to justify the same prediction (see, for example, Brown & L’Engle, 2009). Upon finding the expected phenomenon, researchers rarely go on to test underlying assumptions, consider competing explanations for the same phenomenon, or even address how the findings of the current analyses strengthen or undermine specific aspects of the theory that premised the investigation in the first place. Such theoretical refinements are particularly necessary in the social sciences where many theories are so vague that they cannot be properly falsified (Smaldino, 2017). The failure to systematically refine theory through empirical testing in this area makes it difficult to ascertain the true value of these theories for explaining the effects of pornography use among adolescents.

14.2 The Prevalence of Pornography Use Among Adolescents and Emerging Adults

Although interest in adolescent pornography use has increased dramatically in the last two decades (Koletić, 2017; Peter & Valkenburg, 2016), research of this sort dates back to the President’s Commission on Obscenity and Pornography (Commission on Obscenity and Pornography, 1971). Reviewing data collected before the year 2000 is informative, and helps to provide a context for understanding changes in adolescent pornography exposure that may have occurred with the introduction of the Internet.

14.2.1 Pre-Internet Exposure/Use

Even before the Internet, prevalence research indicated that most adolescents (46–91%; Bryant & Brown, 1989; Lo et al., 1999) had experience with pornography. An early study of American high school students (16–19 years old) selected through stratified random sampling from a single school district in a Midwestern US industrial area reported that 79% of adolescent males and 38% of adolescent females had seen nude photographs of women that displayed genitals and 54% of adolescent males and 15% of adolescent females had viewed a photograph of nude men and women engaging in sexual behavior (Elias, 1971). Similar figures were reported more than a decade later in a sample of secondary students in California, where 83% of adolescent males and 48% of adolescent females had reported exposure to pornography (Cowan & Campbell, 1995). Around the same time, nine out of ten adolescent males and six out of ten adolescent females in a Canadian sample of grade nine students reported exposure to video pornography (Check & Maxwell, 1992). The highest prevalence estimate of adolescent exposure to pornography (91%) during this period was derived from a large (N = 1858) Taiwanese sample of adolescents (grades 10 through 12) toward the close of the millennium (Lo et al., 1999). While the primary sources of pornography in this sample appeared to be television programs (59%) and pornographic comic books (46%), by this time, 38% of male and 7% of female adolescents in this Taiwanese sample reported exposure to pornography on a computer.

Estimates of the average age of first recalled exposure to pornography prior to the year 2000 varied considerably. Early research with a sample of American college students across five North-Eastern campuses indicated that average age of first exposure to pornography may be as low as 11–12 years old (White & Barnett, 1971), while a sample of adolescents collected around the same time suggested that the figure may be closer to 14–15 years old (Elias, 1971). A national probability sample of American adults during this period estimated that first exposure to pornography occurred between the ages of 14 and 17 years for men and 17 and 20 years for women (Wilson & Abelson, 1973). Approximately 10 years later, a report presented to the Attorney General’s Commission on Pornography indicated that the average age of first exposure to pornographic magazines was 14 years, while the average age of exposure to pornographic films was 15 years (Bryant & Brown, 1989). The only American data available from the 1990s suggests that the age of first exposure was 11 years old for boys and 12 years old for girls (Cowan & Campbell, 1995). Figures were comparable for Canadian samples during this period; one National probability sample suggested that the average age of first exposure to pornography occurred between 10 and 15 years of age (Peat and Partners 1984, as cited in Bryant & Brown, 1989), while a smaller convenience sample indicated that the average age of first exposure was under 12 years of age (Check & Maxwell, 1992).

14.2.2 Post-Internet (Online) Exposure/Use

The accessibility of Internet pornography changed dramatically through the late 1990s and early 2000s (Barss, 2011), re-igniting fears about young people’s pornography use. Consequently, much of the contemporary literature concerning adolescent pornography use concentrates on online pornography use and the number of such estimates has increased dramatically since the early 2000s. Although there is a notable concentration of research in the United States (Bleakley et al., 2011; Hardy et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2003, 2007; Wolak et al., 2007; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005; Ybarra et al., 2011) and the Netherlands (Doornwaard et al., 2015; Peter & Valkenburg, 2006, 2008, 2011b, 2011c), estimates of adolescent pornography use have been examined in a wide range of other countries, including Australia (Flood, 2009; Hasking et al., 2011), Belgium (Beyens et al., 2015; Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2013), China (Dong et al., 2013), the Czech Republic (Ševčíková & Daneback, 2014), Croatia (Tomić et al., 2018), Ethiopia (Bogale & Seme, 2014), Germany (Weber et al., 2012), Greece (Tsitsika et al., 2009), Israel (Mesch, 2009), Hong Kong (Ma & Shek, 2013; Shek & Ma, 2012a, 2012b; To et al., 2012), Italy (Bonino et al., 2006), Korea (Kim, 2001, 2011), Malaysia (Manaf et al., 2014), Morocco (Kadri et al., 2013), Sweden (Häggström-Nordin et al., 2011; Skoog et al., 2009), Switzerland (Luder et al., 2011), and Taiwan (Chen et al., 2013). Sexual norms across these countries diverge considerably, and it is likely that some of the variation in estimates of adolescent pornography use may be attributable to cultural differences.

The range between the lowest and highest estimates of the prevalence of adolescent pornography use appears extreme. For example, Flood (2009) noted that only 2% of female and 38% of male adolescents (16–17 years of age) in an Australian sample purposefully accessed pornographic websites, while Weber and his colleagues (2012) indicated that 81% of female and 98% of male adolescents (16–19 years of age) in Germany had ever seen a pornographic movie. Certainly, some of the difference between these estimates can be attributable to factors like age, degree of parental supervision, and culture, but another important factor concerns how exposure to pornography is measured. In their recent review, Peter and Valkenburg (2016) differentiated between three measurement approaches that may be relevant here: those that measure unintentional exposure (e.g., unsolicited e-mails, URL redirects, peer exposure), those that measure intentional exposure, and those that measure any exposure. According to their overview, between 19 and 84% of adolescents were unintentionally exposed to pornography, between 7 and 59% of adolescents have purposely viewed pornography, and between 7 and 71% of adolescents had any exposure to pornography (Peter & Valkenburg, 2016). While these estimates also represent very broad ranges, it is noteworthy that studies that conduct direct comparisons typically report that unintentional exposure is more common than intentional exposure among adolescents (Chen et al., 2013; Flood, 2009; Luder et al., 2011; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005), though there are some exceptions (Weber et al., 2012).

Estimates of age at first exposure to pornography since the early 2000s are less variable than estimates before this period, but do not appear to be considerably lower. An early study of Danish men and women between the ages of 18 and 30 years reported mean first exposure to pornography of 13 years for men and 15 years for women (Hald, 2006). American samples of comparable ages reported similar estimates for men (12–14 years) and women (15 years) (Morgan, 2011; Sabina et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2016). A sample of American college students surveyed during this period also indicated that the average age of first exposure to pornography was 14 years old for men and 15 years old women, and few men (3.5%) and women (1.5%) reported exposure before 12 years of age (Sabina et al., 2008). Median ages of first exposure to pornography of 13 years old for males and 14 years old for females have also been reported from a large sample of Swedish adolescents and young adults (ages 16–23) (Mattebo et al., 2014). A Croatian study carried out in a large-scale national probability-based sample of emerging adults found that mean age at first exposure was between 11 and 12 years for male and 13 and 14 years for female participants (Sinković et al., 2013). Interestingly, limited evidence indicates that age of first exposure to pornography may precede regular use of pornography by several years (Miller et al., 2018).

14.2.3 Changes in Pornography Use across Adolescence

Consistent with Miller et al.’s observation of delayed habitual use, several longitudinal samples of adolescents suggest that the frequency of pornography use increases with age (Cranney et al., 2018; Doornwaard et al., 2015; Rasmussen & Bierman, 2016). For example, data from a nationally representative panel of adolescents in the United States indicate that the frequency of pornography use increases in both males and females (Rasmussen & Bierman, 2016). Among the limited number of available studies, there is some indication that pornography use begins earlier (Willoughby et al., 2018), and that growth in the frequency of pornography use is higher among male adolescents than female adolescents (Doornwaard et al., 2015; Rasmussen & Bierman, 2016). There has also been some consideration of the role of religiosity, though the reported effects are contentious. Research in the United States suggests that externalized religiosity (e.g., church attendance) suppresses growth in pornography use among adolescents (Rasmussen & Bierman, 2016), while research in Croatia does not (Cranney et al., 2018). Further examination of the Croatian panel has provided some corroboration of the American findings when it comes to indicators of internalized religiosity (e.g., belief in God), but only among adolescents who do not exhibit symptoms of problematic pornography use in later adolescence (Kohut & Štulhofer, 2018b). Among those who do express symptoms of problematic pornography use, religiosity is associated with a delayed onset of pornography use but a higher rate of change over time. Finally, abstention from pornography use has also been found to be more common among religious individuals in a study that examined adult recollections of pornography use during adolescence (Willoughby et al., 2018), although the effect of social desirability cannot be ruled out.

14.2.4 Exposure to and Use of Pornography: Correlates, Predictors, and Potential Confounds

In the broader literature, pornography use is typically framed as a unique causal agent that negatively impacts how people think, feel, and behave. Despite the preponderance of causal theorizing, most of the available research is correlational in nature and much of it fails to rule out plausible alternative hypotheses for established associations between pornography use and its presumed harms (Campbell & Kohut, 2017). Fortunately, research within the specific domain of adolescent pornography use appears to be somewhat less prone to such errors (see, for example, Brown & L’Engle, 2009; Ybarra et al., 2011). Moreover, research with adolescent samples has identified a number of correlates that are unlikely to be direct consequences of pornography use, such as impulsiveness and sensation seeking (Brown & L’Engle, 2009), self-control and religiosity (Hardy et al., 2013), pubertal status (Beyens et al., 2015; Peter & Valkenburg, 2006), victimization (Dong et al., 2013), non-sexual delinquent behavior (Wolak et al., 2007), substance use (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005), family dynamics (Mesch, 2009), peer influence (Weber et al., 2012), and the extent of overall Internet use (Mitchell et al., 2003). Further research in this area would do well to rule out these and other potential confounding factors when examining presumed causal relationships.

14.3 Pornography Use and Sexual Risk Taking

Recent reports on the relationship between pornography use and adolescents’ well-being (Martellozzo et al., 2016; Quadara et al., 2017) have pointed to potential links between pornography use and risky sexual behavior as a major concern. Due to risky sexual behaviors, adolescents have the highest age-specific proportion of unintended pregnancies and the highest age-specific risk for acquiring sexually transmitted infections (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). These public health concerns have yielded extensive research into psychosocial and cultural determinants of adolescent sexual risk taking (Kotchick et al., 2001; Zimmer-Gembeck & Helfand, 2008), but only a minority of studies have addressed the potential role of pornography use in adolescents’ sexual risk taking.

Taking into account commonly used measures of sexual risk taking (condom use, number of sexual partners, and age of sexual debut), the existing evidence of the association between adolescents’ pornography use and risky sexual behavior is mixed. A significant association between not using a condom at most recent sexual intercourse and the frequency of pornography use was reported in three cross-sectional studies carried out among female African-American adolescents (Wingood et al., 2001), male Swiss adolescents (Luder et al., 2011), and emerging adults from the USA (Wright et al., 2016b). In contrast, cross-sectional studies carried out among Australian and US adolescents and young adults (Braun-Courville & Rojas, 2009; Lim et al., 2017), as well as emerging Croatian adults (Sinković et al., 2013) reported no relationship between pornography use and condom use. A two-wave study of Dutch and a five-wave study of Croatian adolescents also failed to corroborate the link (Koletić et al., 2019b; Peter & Valkenburg, 2011b).

The association between pornography use and multiple sexual partnerships was confirmed in three cross-sectional studies carried out in the USA (Braun-Courville & Rojas, 2009; Wingood et al., 2001; Wright et al., 2016b), but not in Australian (Lim et al., 2017), Croatian (Sinković et al., 2013), and Swiss research (Luder et al., 2011). Longitudinal evidence is also mixed. A recent Canadian longitudinal study observed that participants who were characterized by early exposure to pornography and regular pornography use reported substantially more sexual partners compared to their peers (Rasmussen & Bierman, 2018). However, another study that explored links between recollections of early onset of pornography on the one hand and number of romantic partners and frequency of intercourse among emerging adults on the other hand did not find significant associations (Willoughby et al., 2018). A more recent Croatian study reported non-significant association between frequency of pornography use and multiple sexual partnership in two independent panel samples of adolescents (Koletić et al., 2019b).

With respect to the association between pornography use and adolescents’ sexual debut, a couple of two-wave studies found a positive link among US and Belgian adolescents, respectively (Brown & L’Engle, 2009; Vandenbosch & Eggermont, 2013). A four-wave Dutch study also found a significant association between the two constructs, but only among male adolescents between the first two study waves (Doornwaard et al., 2015). In contrast to the Dutch study, a consistent non-significant longitudinal association between male adolescents’ pornography use and sexual debut was reported in two independent panels of Croatian adolescents (Matković et al., 2018). The findings in female adolescents were inconclusive.

By including risky sexual practices other than condom non-use and number of sexual partners (e.g., one-night stands, intoxication prior to sexual intercourse), a couple of cross-sectional studies have examined the target association using a composite measure of sexual risk taking. According to Braun-Courville and Rojas (2009), adolescent online pornography users had significantly higher scores on a risky sexual behavior scale than non-users. In contrast, Lim et al. (2017) reported a non-significant association between the use of sexually explicit material and another composite sexual risk scale. In a recent three-wave longitudinal study of adolescents, higher baseline frequency of pornography use predicted a steeper increase in male adolescents’ composite sexual risk scores over a period of 15 months (Koletić et al., 2019c). A significant positive association between baseline pornography use and sexual risk taking was also found among female adolescents.

Research in adults suggests that both the age of first exposure to pornography and the frequency of pornography use among men who have sex with other men are correlated with unprotected anal intercourse (Perry et al., 2019). However, there is also evidence that specific content (i.e., depiction of condomless anal sex) in pornography may be more important than general pornography use (Rosser et al., 2013; Schrimshaw et al., 2016; Whitfield et al., 2018). Comparable research among young gay and bisexual men is sorely lacking (see Nelson et al., 2016), despite the fact that sexual minority youth might be even more vulnerable due to bullying, as well as external and internalized homonegativity—constructs that have been linked to sexual risk taking in a large-scale cross-cultural research (Ross et al., 2013).

Inconsistent findings from the presented studies may stem from several methodological and contextual differences. First, age range and gender ratio differed across both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Second, the studies used markedly different operationalizations of pornography use and sexual risk taking. Third, objective indicators of sexual risk taking or its correlates were used only exceptionally, raising questions about culture-specific social desirability biases. The exceptions were vaginal specimen-based STI testing (Wingood et al., 2001) and salivary testosterone assessment of pubertal development (Koletić et al., 2019b). Fourth, control variables were used inconsistently across the available studies. Finally, given that the majority of the studies were conducted in fairly liberal and sexually permissive cultural settings, there is a notable lack of cultural heterogeneity in the body of research focusing on young people’s pornography use and sexual risk taking.

14.4 Pornography and Sexual Aggression

Whether or not pornography use contributes to sexual aggression remains a contentious issue. Literature reviews and meta-analytic summaries concerning the link between pornography use and sexual aggression continue to arrive at conflicting conclusions, variously asserting that pornography contributes to sexual aggression (Wright et al., 2016a), that it does not contribute to sexual aggression (Ferguson & Hartley, 2009; Mellor & Duff, 2019), or that pornography use may be a risk factor for sexual aggression but only (or primarily) among individuals who are predisposed to sexual aggression (Fisher et al., 2013; Kingston et al., 2009; Malamuth, 2018; Seto et al., 2001). It is notable that several researchers have indicated difficulties with integrating research findings in this field because of inconsistent operational definitions of pornography use across studies (Mellor & Duff, 2019; Seto et al., 2001).

Several studies have linked pornography use among adolescents to beliefs about victim-precipitated rape, more endorsement of traditional gender roles, and more acceptance of other rape-supportive attitudes (Brown & L’Engle, 2009; Check & Maxwell, 1992; Cowan & Campbell, 1995; Stanley et al., 2018; Ybarra et al., 2011). Perhaps more importantly, a combination of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies suggests that pornography use is associated with self-reported sexual harassment, sexual assault, and rape (Bonino et al., 2006; Brown & L’Engle, 2009; Kjellgren et al., 2010, 2011; Ybarra & Thompson, 2018). Overall, such findings suggest that pornography is implicated in the commission of sexual violence.

There are several reasons, however, to question the view that pornography use causes sexual violence. To being with, a recent systematic review of juvenile offender research has concluded that such studies have not established a consistent link between pornography use in childhood and adolescence and subsequent sexual offending (Mellor & Duff, 2019). Further, much of the correlational research demonstrating connections between pornography use and rape supportive attitudes has failed to adequately control for potential confounding variables (e.g., delinquency, substance use, impulsiveness) and the research that has controlled for such variables typically has not found such associations. The work of Kjellgren et al. (2010) illustrates this well. An examination of a large national sample of Swedish male adolescents in their third year of high school indicated that sexually coercive male adolescents were more likely to report frequent pornography use, viewing violent pornography, having friends who use pornography frequently, and having friends who like violent pornography than male adolescents who did not engage in sexual coercion and had no conduct disorder problems. However, the same differences were found when male adolescents with non-sexual conduct problems were compared to those who did not have such problems. Moreover, none of these variables distinguished between sexually violent adolescents and their peers with non-sexual conduct problems in multivariate analyses that controlled for potential confounding variables. Lastly, research that adequately controls for confounding variables has found that violent pornography use is associated with sexually violent behavior while use of non-violent pornography is not (Kjellgren et al., 2011; Ybarra et al., 2011; Ybarra & Thompson, 2018). Taken together, such findings suggest that links between sexual aggression and non-violent pornography use among adolescents may partially result from confounding with other putative causes of sexual violence (e.g., substance use, conduct disorder).

While it appears that use of pornography, particularly aggressive or violent content, may be implicated in the enactment of some sort of sexual violence, it remains difficult to determine whether non-violent pornography use plays an important causal role. As Mesch (2009) has previously pointed out, research tends to indicate that “despite the wide availability of pornographic material on the Internet, its consumption at high frequency is more a characteristic of troubled adolescents who lack a sense of being part of the society and positive attitudes to school, and report problematic relations with their families.” Given the connections between such individual characteristics and sexual aggression, correlational research is likely to reveal associations between pornography use and sexual violence (particularly in large and heterogeneous samples) even if pornography is not a causal contributor.

14.5 Pornography Use and Young People’s Psychological Health and Sexual Well-Being

Several issues have been raised in the research literature regarding young people’s pornography use, psychological health, and sexual well-being. In most cases, empirical assessments focused on potential harms related to pornography use, such as negative mood, compulsive pornography use, pornography-related sexual dysfunction, as well as reporting lower sexual satisfaction.

Research interest in compulsive use of pornography has been increasing, particularly in the past decade (see, for example, Grubbs et al., 2015; Kraus et al., 2016; Werner et al., 2018). Despite the fact that adolescents may be especially vulnerable to problematic use of pornography, due to developmental (neurobiological and socio-psychological) characteristics (Owens et al., 2012), only a handful of studies have recently addressed the phenomenon among adolescents—possibly due to ethical concerns and constraints. In the first of the two cross-sectional studies, which were carried out in three samples of Israeli adolescents, a weak association between compulsive sexual behavior (over a third of items from the composite measure that was used to assess the construct asked about pornography use) and psychopathology scores was observed (Efrati, 2018). In the second study (Efrati & Gola, 2018), the authors reported three latent profiles of adolescent pornography users, with 12% of participants belonging to a group that scored high on four dimensions associated with compulsive sexuality (sex as affect regulating behavior; perceived lack of control over sexual behavior; adverse effects of sexual behavior; and unwanted consequences of sexual behavior). In comparison to the other two latent profile groups, this compulsive sexual behavior group was characterized as having a higher external locus of control, greater loneliness, a more anxious attachment style, and, expectedly, higher frequency of pornography use. Finally, a longitudinal study that included male adolescents from two independent panel samples found a significant, albeit weak, association between baseline pornography use (at the age of 16) and scores on a brief Compulsive Pornography Consumption scale 2 years later (Kohut & Štulhofer, 2018b). Controlling for sensation seeking, impulsivity, and social desirability, a consistent link between growth in pornography use over time and symptoms of sexual compulsiveness at the final wave was observed only among more religious adolescents. Taken together, these studies’ findings suggest that some adolescents may benefit from educational interventions and counseling focused on problematic pornography use and emphasize a need for more data about the phenomenon.

High prevalence of pornography use among male adolescents and emerging adults, which has been observed in different cultural settings, and an apparent coinciding increase in erectile dysfunction prompted claims about an epidemic of pornography-induced erectile dysfunction among young men (de Alarcón et al., 2019). Although the idea that high pornography use reduces sexual desire for real life partners, resulting in erectile difficulties, seems to have gotten some traction in the popular media and online discussion groups, particularly in the USA (Grubbs et al., 2019), the concept remains highly controversial (Ley et al., 2014). Taking into account a lack of rigorous studies on sexual dysfunctions in adolescence and emerging adulthood, which reflects consistent observations of a negative association between age and erectile function, empirical support for pornography-induced erectile dysfunction among men 20–40 years old is lacking (Berger et al., 2019; Landripet & Štulhofer, 2015).

A more general line of research is represented by studies that explored possible links between pornography use and adolescent psychological health and subjective well-being. Taken together, cross-sectional evidence remains contradictory: negative links, no associations, and even positive relationships have been reported (Kim, 2001, 2011; Morrison et al., 2006; Peter & Valkenburg, 2016; Ybarra et al., 2011). Similarly, a recent study found that adults who retrospectively reported early adolescent initiation into and continued use of pornography were characterized by lower life satisfaction, but not higher depression, than those who had rarely used pornography during adolescence (Willoughby et al., 2018). Additional longitudinal evidence is sparse, but points to no association between pornography use and various indicators of adolescents’ psychological health and well-being. The first of the four available studies reported a relationship between lower life satisfaction at Time 1 and higher frequency of pornography use at Time 2 (Peter & Valkenburg, 2011b, 2011c). The other three studies found no substantial associations between pornography use and physical self-esteem (Doornwaard et al., 2015), subjective well-being, general self-esteem, and symptoms of depression and anxiety (Kohut & Štulhofer, 2018a; Štulhofer et al., 2019)—regardless of the patterns of change in the frequency of pornography use (Štulhofer et al., 2019). However, the authors of these two most recent longitudinal studies noted that their assessment did not rule out the possibility of pornography use being related to depression and anxiety symptoms, as well as self-esteem, in early adolescent girls.

A recent meta-analysis of studies carried out mostly in adult samples found a small but significant negative association between the frequency of pornography use and sexual satisfaction in men, but no association between pornography use and measures of intrapersonal satisfaction (e.g., self-esteem, body satisfaction) in either men or women (Wright et al., 2017). The authors suggested that social comparison theory provides a fruitful framework for understanding the negative relationship, but warned against oversimplifying underlying mechanisms (e.g., the meta-analysis observed no link between pornography use and body satisfaction). Only three longitudinal studies have explored the association between pornography use and sexual satisfaction in adolescents and emerging adults. The first two, both carried out in the Netherlands, found small but significant relationships in both genders (Doornwaard et al., 2015; Peter & Valkenburg, 2009). It should be noted that the two studies sampled participants in different developmental phases (participants’ ages ranged from 10 to 18 years in the former and from 13 to 20 years in the latter study), which impedes more precise insights. More recently, a longitudinal study that followed a sample of 16-year-old participants for 2 years observed no significant associations in either female or male adolescents between baseline level and change in pornography use over time and sexual satisfaction levels reported at the end of the study, controlling for satisfaction levels at the previous data collection wave (Milas et al., 2019). Considering these conflicting findings, more research is warranted before any conclusions are made.

Finally, a number of qualitative studies have pointed to the fact that pornography is also used by adolescents and young adults as a source of information about sex and sexuality (see, for example, Litras et al., 2015; Löfgren-Mårtenson & Månsson, 2010; Rothman et al., 2015; Scarcelli, 2015). This may be particularly relevant for young lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals, for whom relevant information is often not readily available offline (Kubicek et al., 2010; Mustanski et al., 2011). However, navigating the landscape of pornographic imagery may be difficult for young people, particularly if they lack critical thinking skills and other sources of information about human sexuality. In such cases, informational benefits might be offset by specific biases and distortions embedded in pornography.

14.6 Emerging Insights on Pornography Literacy and the Role of Parents

Rising concerns about young people’s pornography use have prompted thinking about possible educational interventions to minimize adverse outcomes. Based on evidence that media literacy programs can reduce risky behaviors associated particularly with media use in adolescents (see Vahedi et al., 2018), ideas about promoting pornography literacy —which can be defined as the ability to think critically about pornographic imagery—

have been gaining popularity (Albury, 2014; Dawson et al., 2019). This critical understanding of pornography, and the related awareness of its norms (unemotional and sexually disinhibited performance), power differential (eroticized gender inequality), and unrealistic body appearance and performance expectations, has been suggested as the solution for problems associated with adolescents’ and young adults’ online exposure to sexually explicit material (Dawson et al., 2019; Rothman et al., 2018; Vandenbosch & van Oosten, 2017).

Due to the contemporary moral climate surrounding the issue of pornography use among young people, but also, more generally, sex-positive teaching (Fortenberry, 2016), pornography literacy would likely be difficult to incorporate in school-based health and sexuality education programs (Albury, 2014). A notable exception seems to be the Netherlands, where a recent longitudinal study found that addressing pornography in sexuality education curriculum weakened the link between online pornography use and sexist attitudes (Vandenbosch & van Oosten, 2017). Recently, a 5-session program in pornography literacy was piloted and evaluated in a group of adolescents and emerging adults from the USA (Rothman et al., 2018). The authors found the program’s implementation feasible from the perspective of both parents and students. Although several expected differences in pre- and post-intervention knowledge about and attitudes toward pornography were noted, low statistical power and the lack of correction for multiple comparisons render the reported findings suggestive at best.

Currently, pornography literacy interventions appear to be a promising idea. Although there is some evidence that addressing pornography in school-based sexuality education can be beneficial (Vandenbosch & van Oosten, 2017), next to nothing is known about what actually works in teaching pornography literacy, whether a behavioral change is feasible, and whether the outcomes are long lasting. It is likely that pornography literacy interventions will become more popular in the future—either as a part of comprehensive sexuality education or as stand-alone programs—which will require rigorous evaluation studies to ascertain whether helping young people to adopt a more critical understanding of sexually explicit material may reduce their vulnerability to pornography-related adverse outcomes.

Parents may also play a role in mitigating the potential harms of pornography use among adolescents. Theoretically, parents may regulate their children’s access to pornography either directly, via restricting or monitoring Internet use, or indirectly, by restricting or monitoring contact with some peers. More lastingly, they may reduce children’s vulnerability to pornography by actively shaping their sexual value systems, by modeling healthy relationships and behaviors, or by providing children with critical thinking tools that will help them challenge pornographic scripts. Parents who are highly engaged in their children’s upbringing and socialization, who provide rules and guidance, emotional support, and encourage autonomy and communication, may minimize the risk of negative outcomes associated with pornography use. Despite the fact that parents are often either overconfident in their ability to monitor their children’s online activities, or feel ill-equipped to deal with it (Clark, 2014), there is some preliminary evidence that parents can have a role in shaping adolescents’ experiences with pornography. A cross-sectional Croatian study, for example, found that parental monitoring was related to less pornography use at the age of 16 years (Tomić et al., 2018), while a longitudinal exploration observed a negative association between male Dutch adolescents’ pornography use and parental rule setting for Internet use (Doornwaard et al., 2015). Given the rising concerns among parents regarding sexualized online content, researchers are encouraged to explore and elucidate mechanisms that may underlie socialization-based reductions in adolescent vulnerability to adverse outcomes of pornography use.

14.7 Recommendations for Future Research

At present, the field of research concerning young people’s pornography use and its consequences is moderately theoretically informed, empirically insightful but inconsistent in quality, and steadily growing. Overall, quantitative cross-sectional studies carried out in North America, Australia, and Western Europe predominate the field, with markedly conflicting findings (e.g., research findings on pornography use and sexual risk taking). In a great majority of cases, researchers have been preoccupied with negative effects of pornography use, to the point of occasionally exhibiting a moral bias by assuming that pornography use is problematic behavior per se. In addition, many empirical observations are only loosely conceptualized, resulting in the data not being used to test and further develop explanatory theories in the field.

Taken together, do findings on the effects of young people’s pornography use represent a comprehensive body of evidence that can guide educational and other policies? At present, the authors of this chapter see the current contradictions in research findings as a substantial obstacle to optimism. However, the current lack of consensus about adverse outcomes associated with pornography use—who is affected and how?—should not be perceived as discouraging, but rather as an imperative to improve the quality of our explorations. To this aim, in this section, we briefly note a number of points intended to improve scientific quality and rigor in the field, and strengthen its pragmatic role—to inform and assist policies focusing on young people’s psychological, sexual, and reproductive health and well-being.

14.7.1 Using Data to Test Theories

There are various legitimate ways to engage in the scientific method, one of which involves testing theoretical explanations for a phenomenon with empirical observations. Research concerning adolescent pornography use could do more in this regard. At the outset of a study’s design, researchers should carefully consider alternative theoretical explanations that justify the same empirical prediction and craft elements of the study to test competing hypotheses. At a study’s conclusion, researchers should spend more time reflecting on how their specific findings inform the credibility of the theory or theories that provided the study’s rationale. Moreover, regardless of the results (i.e., whether a specific prediction is confirmed or disconfirmed), subsequent efforts should be undertaken to test the implicit and explicit assumptions that underlie the original hypothesis.

Suppose, for example, that a researcher believed pornography contributes to risky sexual behavior through the process of script acquisition, activation, and application (Wright, 2014). Simply demonstrating that self-reported pornography use is associated with self-reported risky sexual behavior tells us virtually nothing about the explanatory value of the 3AM . It could be the case, for example, that such an association is not the result of script acquisition at all, but occurs because both pornography use and sexual risk taking are characteristic behavioral expressions of someone who is unrestricted in their sociosexuality (Simpson & Gangestad, 1991). The careful design of research, systematic reflections on what patterns of findings mean for the credibility of a theory, and systematic follow-up research would be needed to disambiguate these alternative explanations for the same phenomenon.

14.7.2 Terminology and the Importance of Defining the Construct

Considering technological changes that made online pornography the predominant source of sexually explicit material for adolescents and young adults, it would make sense for researchers to systematically adopt terms such as online pornography or Internet pornography in their work.Footnote 1 Although some researchers use the terms pornography and sexually explicit material/media interchangeably—or even prefer the latter expression as a more neutral term—sexually explicit material is less precise and is a potentially broader construct. Apart from the terminology issue, researchers who ask adolescents about their use of “pornography” should always provide a definition of this construct for participants and clearly state such definitions in their papers (Willoughby & Busby, 2015), which is still not standard procedure (Peter & Valkenburg, 2016; Short et al., 2012).

There are a variety of definitions of pornography in the literature (see, for example, Baer et al., 2015; Hald, 2006; Peter & Valkenburg, 2010; Štulhofer et al., 2019), but none of them have been widely accepted. In an effort to improve conceptual consensus in the field, Kohut et al. (2020) recently reviewed academic definitions of pornography, empirical research concerning lay conceptualizations of pornography, and elaborated on potential meanings of the use of such materials, to offer the following conceptual definition of pornography use:

Pornography use is a common but stigmatized behavior, in which one or more people intentionally expose themselves to representations of nudity which may or may not include depictions of sexual behavior, or who seek out, create, modify, exchange, or store such materials. Pornography use, which is primarily for sexual purposes, can involve one or more types of online and offline materials, and can occur in a variety of locational, social, and behavioral contexts. The extent and nature of such behaviors are regulated and shaped by a combination of personal and social hedonic motives, as well as other individual differences and environmental factors. Pornography use can evoke immediate sexual and affective responses, and may contribute to more lasting cognitive, affective, and behavioral changes (Kohut et al., 2020, p. 37).

However, in some cases—for example, when exploring the link between pornography use and sexual risk taking—researchers should define pornography more narrowly (see Koletić et al., 2019b), so that participants would only consider their use of material that contains explicit presentation of sexual behaviors, usually focusing on penetrative sexual activities.

14.7.3 Measurement Issues

Currently, there are very few commonly used measures of pornography use across studies (Kohut et al., 2020; Short et al., 2012). This state of affairs hinders direct comparisons of research findings across studies and may be partially responsible for some of the inconsistencies that are present in this field (Mellor & Duff, 2019; Peter & Valkenburg, 2016; Seto et al., 2001). Having recognized this issue, it is critical for the research community to systematically adopt common measures of pornography use that have been well validated. Some preliminary validation work has been offered for several multi-item scales (Hald, 2006; Peter & Valkenburg, 2006), but, critically, criterion validity involving objective measures of pornography use behavior (e.g., movie rentals, pay-per-view records, browser history, Internet browsing logs) has yet to be considered. Related research concerning the validation of measures of self-reported smartphone use has found that existing measures do not always reflect participants’ actual behavior (correlations range from 0.13 to 0.40; Ellis et al., 2019). Given such findings, researchers in the field of pornography should be cautious when interpreting their results until evidence of criterion validity is offered.

The first measurement-related issue that must be confronted concerns the nature of pornography use behavior that researchers are most interested in. As is already recognized, intentional use can be distinguished from unintentional exposure. If intentional use is of most interest, it is a broad construct that may include seeking out or exposing oneself to pornography, or creating, modifying, storing, or exchanging such materials, and researchers may wish to focus their attention on a limited number of these behavioral facets. If self-exposure is of most relevance, researchers still must decide whether they should be measuring duration of use (i.e., the difference between current age and age of first use), frequency of use (i.e., number of uses over a period of time), temporal use (i.e., the amount of time spent in an assessment window), or time since last use, or some combination of these factors. Pornography use can also occur in a variety of contexts that may have some bearing on relevant antecedents and consequences, so researchers may also need to consider the relevance of online/offline use, private/public use, solitary/partnered/social use, masturbatory/non-masturbatory use, etc.

Once the specific nature of pornography use is clarified, a decision must also be made between the use of single-item versus multi-item assessments. It is often assumed that multi-item approaches improve the reliability of measures in the field. While this makes sense, there is evidence that single-item measures can perform as well as multi-item indicators under specific limited circumstances (Bergkvist & Rossiter, 2007), or even outperform them, as appears to be the case when it comes to predicting the actual time that users spend on their smartphones (Ellis et al., 2019). However, a further consideration in favor of multi-item assessments stems from the fact that researchers need not ask participants about their “pornography” use directly, and instead, ask them about how often they use materials with specific characteristics (e.g., “An image of a heterosexual couple having sex which shows the man’s penis penetrating the woman”) (Leonhardt & Willoughby, 2019). The advantage of such an approach is that it may reduce error introduced by variations in participants’ understanding of the concept of pornography (Willoughby & Busby, 2015). While advocates of single-item assessments can certainly adopt this approach, the use of multiple items—provided they are not redundant—would allow for a more thorough assessment of the breadth of construct of pornography. In a very similar way, multi-item assessments could also be easily extended to measure the use of specific types of sexual content without invoking concepts that are explicitly undesirable (e.g., “rape” pornography), or theoretically contested (e.g., “violent” pornography). The proper measurement of pornography use, as well as specific and theoretically relevant content features of pornography, is an area that deserves a great deal of attention.

To reiterate a recommendation by Peter and Valkenburg (2016), participants’ preferred type of pornographic content should be also inquired about whenever possible, as specific content, rather than sheer frequency of pornography use, may be an indicator of vulnerability to adverse outcomes (see, for example, Štulhofer et al., 2010). However, how to best assess the usage of or preference for specific content is currently unclear, as validated measures are rare (Hald et al., 2018; Landripet et al., 2019; Vandenbosch, 2015).

14.7.4 Research Design

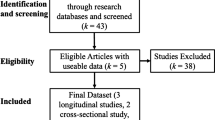

Considering that experimental studies are problematic in this area,Footnote 2 more high-quality longitudinal studies are needed. Although several longitudinal studies with a focus on adolescents’ use of pornography emerged in the past decade (Koletić, 2017), the field remains overpopulated by cross-sectional research studies of varying quality. Considering the developmental processes that characterize adolescence and, consequently, the importance of exploring links (both at between- and within-individual levels) between changes in pornography use and various adverse outcomes over time, researchers should be encouraged to plan for longitudinal, rather than cross-sectional, assessment. To start disentangling the question of directionality—for example, between pornography use and sexual satisfaction—at least two observation points would be needed. Similarly, to carry out a true (i.e., conceptually valid and methodologically sound) mediation analysis would require at least three observation points (Kline, 2015; Little et al., 2009). In short, we believe that further development of this research field will primarily depend on high-quality longitudinal explorations.

Three important points regarding longitudinal design should be briefly mentioned here. First, the majority of existing longitudinal studies concerning pornography use have sampled participants of different ages, often ranging from early adolescence to emerging adulthood (see Koletić, 2017). This is unfortunate, because such approaches preclude age- or developmental phase-specific findings. To avoid such “pooled” estimates, which cannot be confidently attributed to any particular age group, future panel samples should either recruit a specific age cohort or, provided the sample size is sufficiently large to carry out key analyses separately by age group, several cohorts. Secondly, the risk of systematic dropout should be seriously considered and assessed. Although most of the longitudinal studies in the field incorporate an attrition bias analysis or control for attrition in regression models by including the corresponding dummy variable as a predictor, such approaches have typically not determined whether the most vulnerable participants were more likely than their peers to leave the study before it concluded. We would recommend that future studies define study-specific vulnerability (i.e., characteristics that make an individual more vulnerable to a particular pornography-related outcome), include its operationalization in the survey materials, and explore systematic drop-out in parallel with data collection to make sure that their final estimates represent both participants with lower and higher theoretical vulnerability to pornography. Finally, longitudinal studies in sexually explicit media effects among non-heterosexual youth are sorely lacking. Taking into account that LGBT youth are at increased multiple health-related risks (Bontempo & D’Augelli, 2002; Garofalo et al., 1998) due to external and internalized homonegativity, future research should pay particular attention to this population. To successfully recruit a large-enough panel sample of non-heterosexual youth to be followed over time, the standard classroom-based surveying will likely need to be replaced with targeted online surveying, possibly relying on a network-based initial recruitment.

14.7.5 Analytical Robustness

It seems that the assessment of possible confounders and moderators of the links between pornography use and the outcomes explored is increasingly more common in the field. The importance of such analysis is impossible to overstate. It has been repeatedly emphasized that possible effects of pornography use are not uniform and that some young people are more vulnerable to adverse outcomes than others (Owens et al., 2012; Peter & Valkenburg, 2016). Exploration of conceptually and empirically plausible moderators at individual, family, and peer levels remains a crucial analytical strategy for identifying more vulnerable individuals. Similarly, potential confounders (e.g., sensation seeking, reduced inhibitory control, sex drive, social desirability) provide reasonable alternative hypotheses for many of the assumed outcomes of pornography use, and consequently need to be routinely included in questionnaires and controlled for in sequential models. We should also note that while we advocate for more longitudinal designs in this area, evidence of temporal precedence from longitudinal research does not rule out the potential role of confounding variables, so they must also be considered in such designs.

14.7.6 Ideological Biases

Taking into account that research in young people’s pornography use is a sensitive and, in many socio-cultural settings, highly controversial topic, future research would benefit from increased awareness about ideological and moral pressures and biases. More specifically, we would suggest that researchers discuss their beliefs and inclinations with other team members before commencing their work on designing a study and, perhaps, consider a brief disclosure in a footnote.

14.7.7 Applied Research

Given the ubiquity of online pornography and difficulties in restricting minors’ access to it, pornography literacy and other educational interventions will likely become increasingly popular with time. Obviously, rigorous evaluation research, which will be needed to assess effectiveness of such programs, will have an important role to play in future educational policies. In our view, such work also presents an opportunity to advance the understanding of psychosocial mechanisms underlying presumed links between pornography use and young people’s attitudes and behaviors in applied settings.

14.8 Conclusions

In the era of easy access to pornography for everyone, including adolescents, increasing concerns about potential adverse effects of such material for young people’s health and well-being are understandable. Although the current evidence is mixed and limited by a number of shortcomings, it seems unlikely that pornography use is uniformly problematic. It is entirely possible, though it remains to be demonstrated, that early exposure to and consistently high frequency of pornography use constitutes a risk for a certain subset of particularly vulnerable young people. However, this does not mean that most young people would not benefit from help in navigating the world of sexualized media and pornographic imagery. Qualitative research elucidates that the majority of adolescents are at least confused, sometimes distressed, when first exposed to pornography. For some, these feelings are longer-lasting. There is a clear role for parents, school-based educators, and dedicated sexuality educators to address the reality of pornography exposure. Although such discussions may not be easy in the contemporary climate in which reasonable caution is too readily replaced with moral condemnation—particularly in the context of sexuality education—open conversations about pornography with parents, educators, and experts working in youth health centers remain essential for young people to make sense of their sexuality, health, and well-being. Fortunately, such discussions are often welcomed by young people (Dawson et al., 2019; Rothman et al., 2015) as they frequently desire more information about such topics than they are given. As researchers of pornography use among adolescents, it should be our collective goal to strive to provide high-quality evidence to inform these conversations and assist in educational policies.Footnote 3

Notes

- 1.

This is not to say that the term offline pornography may not be relevant in some cases.

- 2.

Given that experimental studies in young people’s pornography use are usually not feasible because of ethical constraints (intentionally exposing minors to pornography is widely seen as unethical) and difficulties in finding male controls (i.e., adolescents who have never been exposed to pornography), well-conducted longitudinal studies remain the best strategy to narrow the gap between correlational analysis and understanding possible causality in this population.

- 3.

References

Albury, K. (2014). Porn and sex education, porn as sex education. Porn Studies, 1(1–2, 172), –181.

Baer, J. L., Kohut, T., & Fisher, W. A. (2015). Is pornography use associated with anti-woman sexual aggression? Re-examining the confluence model with third variable considerations. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 24(2), 160–173.

Barss, P. (2011). The erotic engine: How pornography has powered mass communication, from Gutenberg to Google. Anchor Canada.

Belsky, J. (1997). Variation in susceptibility to environmental influence: An evolutionary argument. Psychological Inquiry, 8(3), 182–186.

Berger, J. H., Kehoe, J. E., Doan, A. P., Crain, D. S., Klam, W. P., Marshall, M. T., & Christman, M. S. (2019). Survey of sexual function and pornography. Military Medicine, 184(11–12), 731–737.

Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. R. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2), 175–184.

Beyens, I., Vandenbosch, L., & Eggermont, S. (2015). Early adolescent boys’ exposure to internet pornography: Relationships to pubertal timing, sensation seeking, and academic performance. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 20, 1–32.

Bleakley, A., Hennessy, M., & Fishbein, M. (2011). A model of adolescents’ seeking of sexual content in their media choices. Journal of Sex Research, 48(4), 309–315.

Bogale, A., & Seme, A. (2014). Premarital sexual practices and its predictors among in-school youths of shendi town, west Gojjam zone, North Western Ethiopia. Reproductive Health, 11(1), 49–58.

Bonino, S., Ciairano, S., Rabaglietti, E., & Cattelino, E. (2006). Use of pornography and self-reported engagement in sexual violence among adolescents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 3(3), 265–288.

Bontempo, D. E., & D’Augelli, A. R. (2002). Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths’ health risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30(5), 364–374.

Braun-Courville, D. K., & Rojas, M. (2009). Exposure to sexually explicit web sites and adolescent sexual attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(2), 156–162.

Brown, J. D. (2000). Adolescents’ sexual media diets. Journal of Adolescent Health, 27(2 Suppl), 35–40.

Brown, J. D., Halpern, C. T., & L’Engle, K. L. (2005). Mass media as a sexual super peer for early maturing girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36(5), 420–427.

Brown, J. D., & L’Engle, K. L. (2009). X-rated: Sexual attitudes and behaviors associated with U.S. early adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit media. Communication Research, 36(1), 129–151.

Bryant, J., & Brown, D. (1989). Uses of pornography. In D. Zillmann & J. Bryant (Eds.), Pornography: Research advances and policy considerations (pp. 25–56). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Byers, L. J., Menzies, K. S., & O’Grady, W. L. (2004). The impact of computer variables on the viewing and sending of sexually explicit material on the Internet: Testing Cooper’s “Triple-A Engine”. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 13(3–4), 157–169.

Campbell, L., & Kohut, T. (2017). The use and effects of pornography in romantic relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 6–10.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2016. Department of Health and Human Services.

Check, J. V. P., & Maxwell, D. K. (1992). Pornography consumption and pro-rape attitudes in children. International Journal of Psychology, 27(3–4), 445.

Chen, A.-S., Leung, M., Chen, C.-H., & Yang, S. C. (2013). Exposure to internet pornography among Taiwanese adolescents. Social Behavior and Personality, 41(1), 157–164.

Citizens for Decent Literature. (1965). Perversion for Profit. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pciD9gd3my0

Clark, A. B. (2014). Parenting through the digital revolution. In F. M. Saleh, A. Grudzinskas, & A. Judge (Eds.), Adolescent sexual behavior in the digital age: Considerations for clinicians, legal professionals, and educators (pp. 247–261). Oxford University Press.

Collins, R. L., Strasburger, V. C., Brown, J. D., Donnerstein, E., Lenhart, A., & Ward, L. M. (2017). Sexual media and childhood well-being and health. Pediatrics, 140, 162–166.

Commission on Obscenity and Pornography. (1971). Technical report of the commission on obscenity and pornography. Washington.

Cooper, A., Delmonico, D. L., & Burg, R. (2000). Cybersex users, abusers, and compulsives: New findings and implications. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 7(1–2), 5–29.

Cooper, A., Delmonico, D. L., Griffin-Shelley, E., & Mathy, R. M. (2004). Online sexual activity: An examination of potentially problematic behaviors. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 11(3), 129–143.

Cowan, G., & Campbell, R. R. (1995). Rape causal attitudes among adolescents. The Journal of Sex Research, 32(2), 145–153.

Cranney, S., Koletić, G., & Štulhofer, A. (2018). Varieties of religious and pornographic experience: Latent growth in adolescents’ religiosity and pornography use. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 28(3), 174–186.

Dawson, K., Nic Gabhainn, S., & Macneela, P. (2019). Toward a model of porn literacy: Core concepts, rationales and approaches. The Journal of Sex Research, 1–15.

de Alarcón, R., de la Iglesia, J. I., Casado, N. M., & Montejo, A. L. (2019). Online porn addiction: What we know and what we don’t—A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(1), 91.

Dong, F., Cao, F., Cheng, P., Cui, N., & Li, Y. (2013). Prevalence and associated factors of poly-victimization in Chinese adolescents. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 54(5), 415–422.

Doornwaard, S. M., Bickham, D. S., Rich, M., ter Bogt, T. F. M., & van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M. (2015). Adolescents’ use of sexually explicit internet material and their sexual attitudes and behavior: Parallel development and directional effects. Developmental Psychology, 51(10), 1476–1488.

Efrati, Y. (2018). Adolescent compulsive sexual behavior: Is it a unique psychological phenomenon? Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(7), 687–700.

Efrati, Y., & Gola, M. (2018). Understanding and predicting profiles of compulsive sexual behavior among adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 1004–1014.

Elias, J. (1971). Exposure of adolescents to erotic materials. In Technical reports of the commission on obscenity and pornography (Vol. 9, pp. 273–311). U.S. Government Printing Office.

Ellis, D. A., Davidson, B. I., Shaw, H., & Geyer, K. (2019). Do smart phone usage scales predict use? International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 130, 86–92.

Elmer-Dewitt, P. (1995). On a screen near you: Cyberporn. Time.

Elmer-Dewitt, P. (2015). Finding Marty Rimm. Retrieved from https://fortune.com/2015/07/01/cyberporn-time-marty-rimm/

Ferguson, C. J., & Hartley, R. D. (2009). The pleasure is momentary…the expense damnable? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14(5), 323–329.