Abstract

Kleine-Levin syndrome (KLS) is a rare neuropsychiatric disorder with a relapsing-remitting course characterized by recurrent episodes of hypersomnia and cognitive and behavioral changes. The pathogenesis is unknown, but it may involve a dysfunction of the mesencephalic-hypothalamic-limbic system. The prevalence of syndrome is estimated to be 1–5 per million with a male/female ratio of 3:1. The typical triad of symptoms is sleep disorder, hyperphagia, and behavioral disorders, especially hypersexuality (above all in males). Between episodes there are long asymptomatic periods of normal sleep, cognition, mood, and behavior.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

29.1 Introduction

Kleine-Levin syndrome (KLS) is a rare neuropsychiatric disorder with a relapsing-remitting course characterized by recurrent episodes of hypersomnia and cognitive and behavioral changes. The first detailed report of multiple cases of recurrent hypersomnia was reported by Kleine in 1925 [1]. In 1936, Levin described seven cases of people with hypersomnia and morbid hunger [2]. In 1962, Critchley named the condition Kleine-Levin syndrome, based on his patients and the previous reports by Kleine and Levin [3]. Subsequent reports by Hoffman and Critchley identified the characteristic features of this condition: male predominance, onset during adolescence, pathological hunger, and the tendency of the syndrome to disappear spontaneously.

The exact cause of KLS is unknown. However, given its features, it may involve a dysfunction of the mesencephalic-hypothalamic-limbic system, and according to some authors, there may be an infection. This hypothesis is favored by evidence that KLS often arises as a result of an inflammatory state [4, 5]. For this reason, several studies have looked for associations with human leukocyte antigens, but some associations that seemed significant were not confirmed by subsequent studies [6]. Specific or probable genetic disorders were more frequent in KLS patients than in controls, including Klinefelter syndrome, mental retardation, autism, and idiopathic developmental delay [4].

The prevalence of KLS is estimated to be 1–5 per million [4]. It mainly affects males, with a male/female ratio of 3:1, but affected females have a longer course [7]. Although the familial risk is low (1% per first-degree relative), 5% of all cases are reported in relatives, suggesting an 800–4000-fold increase in risk [8]. The syndrome usually presents in adolescence (80% of cases), but symptoms can start at any age from childhood to adulthood. Regardless of the age of onset, episodes during adulthood are less severe and less sudden [4].

In a study of 186 patients, other neurological or psychiatric disorders were present before the onset of KLS and persisted among 10% of those patients, who were all significantly older and experienced more frequent and longer episodes and periods of incapacity than patients without such comorbidities [7].

Onset in childhood or adulthood is associated with a longer duration than adolescent onset. When the onset is in adolescence, the episodes often gradually diminish after the age of 30. In any case, episodes become less frequent with age and may even disappear (spontaneous remission). Childhood onset is associated with more frequent episodes than adolescent or adult onset [4].

29.2 Clinical Features and Diagnostic Criteria

KLS is classified as recurrent hypersomnia, although it has a number of clinical features. The diagnosis of KLS is usually delayed for several years after the presentation of the first episode, as the symptoms are initially attributed to other sleep disorders. The first episode is often mistaken for an infection, and KLS is typically only diagnosed after several episodes [5]. During the first episode, patients often go to the emergency room, where the common major causes of acute confusion and rapid changes in behavior are excluded. Alcohol or drug use is then investigated, and an MRI/CT study is carried out to exclude other causes, such as cancer, injury, inflammation, and vascular conditions.

Episodes may last from a few days to several weeks, usually with a sudden onset and interruption.

The typical triad of symptoms is sleep disorder, hyperphagia, and behavioral disorders, especially hypersexuality (above all in males). Numerous recent studies have established that hypersomnia is the constant symptom, with hyperphagia and hypersexuality found in no more than half of cases. For this reason they are no longer included in the 2005 revision of the mandatory diagnostic criteria. Most patients also exhibit apathy and derealization [4].

The diagnostic criteria for KLS are: [9, 10]

-

At least two recurrent episodes of excessive drowsiness lasting from 2 days to 5 weeks.

-

Episodes recur at least once every 18 months.

-

Vigilance, cognitive functions, and behavior return to normal between episodes.

-

The hypersomnia cannot be explained by other sleep disorders, neurological disorders, medication, or substance abuse.

-

In addition, at least one of the following must be present during episodes:

-

Cognitive dysfunction

-

Altered perception

-

Eating disorder

-

Disinhibited behavior

-

Between episodes there are long asymptomatic periods of normal sleep, cognition, mood, and behavior. For this reason the disease is considered benign. Episodes may recur 6 months or a year later and tend to become shorter and more spaced out over time, until they finally disappear.

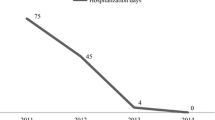

29.3 Clinical Typology (Mild, Moderate, and Severe Forms) [11]

Mild: 1 week 2–3 times a year

Moderate: monthly episodes of 7–10 days or longer episodes at longer intervals

Severe: 40–80 episodes in rapid succession

29.4 Symptoms

29.4.1 Hypersomnia

Patients experience sudden extreme fatigue and an irresistible need to sleep. They typically sleep for an average of 18 h a day or more during the early stages of an episode [12]. Sleep may occur night or day without a clear circadian rhythm. Patients are contactable during episodes and can be awakened, but this makes them aggressive and irritable, and they remain lethargic and apathetic [7].

After several episodes, patients may sleep less but remain inactive and prefer to stay in the dark and away from other people. At the end of an episode, brief insomnia is observed in about two-thirds of patients, sometimes associated with logorrhea and euphoria for 1–3 days. Several studies have reported that sleep patterns and alertness return to normal between episodes.

29.4.2 Cognitive Changes

Almost all patients complain of difficulty in communication (conversation and reading), concentration, decision-making, and memory. They often become unable to perform several tasks at once, have difficulty in motor coordination, and lose track of time. Confusion is generally mild, and patients remain able to count and answer complex questions, but much more slowly than between episodes. Most patients have anterograde amnesia of episodes and are disoriented in time and space [13].

29.4.3 Derealization, Hallucinations, and Delusions

The perception of the environment is altered in almost all patients, leading to derealization. This is the most specific symptom of KLS. Patients experience a feeling of unreality with altered perception of themselves and their environment. They report feeling as if they are inside a dream or a bubble, with changes in and reduced function of all their senses [13].

One-third of patients report threatening or disturbing hallucinations and delusions of short duration. Most perception disorders are mild, but even when more severe, they usually last from a few hours to a few days and stop spontaneously [13].

29.4.4 Eating Disorders

Around three-quarters of patients show eating disorders during episodes. The most typical is ingestion of large amounts of food; in one study patients showed an increase in body weight of 3.2–13.6 kg (7–30 lb.) (most patients gain weight during episodes). A minority of patients (5%) had a total aversion to food during some episodes, but ate more in others [7]. Some patients reduce their food intake, and these patients generally sleep more during episodes than those with hyperphagia [4].

Several authors have noted the compulsive rather than bulimic nature of the eating disorder, as patients did not self-induce vomiting or assume other compensatory behaviors to control their weight. Food craving and hyperphagia were the most critical elements. Some patients went so far as to steal food from shops or from other patients’ plates, searched for food in dustbins, or even used both hands to shovel food in their mouth [14]. Patients with hyperphagia are also uninhibited toward specific tastes (e.g., sweet, salty, or sour) that may not be typical of their usual diet. Affected individuals usually do not recognize that they are particularly hungry but will still consume all available food without considering its condition, quality, or appearance or their personal preferences. Behavior toward food is often repetitive or compulsive.

To summarize, food craving and megaphagia are the most critical elements of KLS-associated eating disorders.

29.4.5 Mood Disorders

Flattened or depressed moods (with rare cases of suicide attempts) are reported in about half of patients and are more frequent in men than in women. They generally last a short time and often occur near the end of an episode. Some teenagers desperately fear that they will never get better, and some may wonder if they will die or say that they want to die if it does not stop [10].

Almost all patients experience irritability, especially if sleep, sexual behavior, or searching for food is prohibited. Anxiety can be accentuated during episodes. Some patients show fear or panic if left alone in unusual places, such as the hospital, or if they have to go outside or meet people [13].

Some patients report long-term mood swings and difficulty adapting to the disorder. This suggests that some patients never fully return to normal between episodes.

29.4.6 Hypersexuality

About half of patients suffer from hypersexuality during episodes. This symptom affects boys more than girls and frequently manifests itself as substantially increased masturbation or propositions toward sexual partners or other people of both sexes. Inappropriate sexual behavior can also occur, including exposing or touching genitals or masturbating in the presence of parents and doctors, using extreme sexual language or touching other people inappropriately [4, 15].

29.4.7 Social Impact

The unpredictable and sudden nature of the episodes means that they have adverse professional and social effects. For example, they may occur at school or during university exams (as they may be triggered by sleep deprivation or stress). Abnormal behavior (e.g., hypersexuality) can cause embarrassment and may even be dangerous.

29.5 Clinical Examination and Testing

Typically, there are no neurological signs on physical examination. Tests aim to exclude EEG epilepsy, focal brain lesions (imaging), meningitis, and encephalitis (by CSF analysis). Most tests are conducted while an episode is in progress [7]. One-quarter of subjects have a normal EEG during the episodes, but 70% show a non-specific and widespread slowdown in EEG activity [7]. No abnormalities are found on CT and MRI [4]. Functional imaging studies show a decrease in temporal lobe, frontal lobe, and thalamic activity during episodes. Functional MRI reveals that memory loss is correlated with reduced activity in the intermediate and adjacent dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and simultaneously increased activity in the medial and anterior thalamus (suggesting increased compensatory effort in controlling memory storage) compared to results in healthy volunteers [16]. The acute onset of cognitive impairment, apathy and derealization, altered perception, uninhibited behavior, anxiety, visual hallucinations, and delusions suggests that the associative cortex is affected.

29.6 Therapy

The objective of treatment is to stop hypersomnia and prevent subsequent episodes. Psychostimulant drugs such as amphetamines, methylphenidate, or pemoline are used to control episodes of drowsiness. Lithium salts [17] or carbamazepine in combination with antidepressants has been used as preventive therapy. A recent meta-analysis by the Cochrane group concluded that there is no evidence to indicate that pharmacological treatment for KLS is effective and safe [18].

References

Kleine W. Periodische Schlafsucht. Eur Neurol. 1925:285–304. https://doi.org/10.1159/000190426.

Levin M. Periodic somnolence and morbid hunger: a new syndrome. Brain. 1936; https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/59.4.494.

Critchley M. Periodic hypersomnia and megaphagia in adolescent males. Brain. 1962; https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/85.4.627.

Arnulf I, Lin L, Gadoth N, et al. Kleine-Levin syndrome: a systematic study of 108 patients. Ann Neurol. 2008; https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.21333.

Huang Y-S, Guilleminault C, Lin K-L, Hwang F-M, Liu F-Y, Kung Y-P. Relationship between Kleine-Levin syndrome and upper respiratory infection in Taiwan. Sleep. 2012; https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1600.

Arnulf I, Lecendreux M, Franco P, Dauvilliers Y. Kleine-Levin syndrome: state of the art. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2008; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2008.04.020.

Arnulf I, Zeitzer JM, File J, Farber N, Mignot E. Kleine-Levin syndrome: a systematic review of 186 cases in the literature. Brain. 2005; https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh620.

Peraita-Adrados R, Vicario JL, Tafti M, García de León M, Billiard M. Monozygotic twins affected with Kleine-Levin syndrome. Sleep. 2012; https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1808.

Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition highlights and modifications. Chest. 2014; https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-0970.

Miglis MG, Guilleminault C. Kleine-Levin syndrome. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-016-0653-6.

Aasm. International classification of sleep disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. (ICSD-2).; 2005.

Arnulf I, Rico TJ, Mignot E. Diagnosis, disease course, and management of patients with Kleine-Levin syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2012; https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70187-4.

Arnulf I, Groos E, Dodet P. Kleine–Levin syndrome: a neuropsychiatric disorder. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2018; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2018.03.005.

Duffy JP, Davison K. A female case of the Kleine-Levin syndrome. Br J Psychiatry. 1968; https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.114.506.77.

Schenck CH, Amulf I, Mahowald MW. Sleep and sex: What can go wrong? A review of the literature on sleep related disorders and abnormal sexual behaviors and experiences. Sleep. 2007; https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/30.6.683.

Engström M, Vigren P, Karlsson T, Landtblom AM. Working memory in 8 Kleine-Levin syndrome patients: an fMRI study. Sleep. 2009; https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/32.5.681.

Abe K. Lithium prophylaxis of periodic hypersomnia. Br J Psychiatry. 1977; https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.130.3.312.

de Oliveira MM, Conti C, Prado GF. Pharmacological treatment for Kleine-Levin syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006685.pub4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Radicioni, A.F., Tarantino, C., Spaziani, M. (2022). Kleine–Levin Syndrome and Eating and Weight Disorders. In: Manzato, E., Cuzzolaro, M., Donini, L.M. (eds) Hidden and Lesser-known Disordered Eating Behaviors in Medical and Psychiatric Conditions . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81174-7_29

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81174-7_29

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-81173-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-81174-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)