Abstract

In this chapter, Willocks and Moralee argue that, within the field of leadership studies, there has been a significant shift away from individualistic, trait and ‘heroic’ ways of conceptualising leadership towards what have been termed ‘post-heroic’ approaches. Leadership-as-practice (LAP) is one such approach that accounts for collective, collaborative and emergent aspects of leadership in the ongoing flow of organisational practices. This chapter attends to the current dearth of empirical examples of LAP, notably within healthcare, by drawing on a UK NHS case study. Their analysis offers insight into different healthcare leadership ‘practices’ and the intricate connections between them, considering conceptual implications by highlighting the tensions and complexities that underpin LAP and the way in which policy context, culture and history inform ongoing emergent leadership processes.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

The Evolution of Leadership in Healthcare

The English National Health Service (NHS) has a long history of initiatives aimed at improving care delivery. Leadership is often considered one of the key ways in which such improvements occur. Traditional leadership models and theories have been dominated by the perspective that leadership is enacted by an individual leader who has a distinct set of traits and competencies (Pearce and Manz 2005). The GLOBE ‘universal’ definition of leadership (House et al. 2002, p.5) captures this as ‘the ability to influence, motivate, and enable others to contribute towards the effectiveness and success of the organization of which they are members’. This top-down understanding of leadership is frequently referred to as the tripod ontology, conceptualising leadership as being comprised of three distinct elements: leader(s), followers and a shared goal that they are working to accomplish together. The majority of leadership theory is built on this three-pronged approach (Drath et al. 2008).

However, within the field of leadership studies, over the last ten years there has been a significant shift in how leadership is conceptualised. As a consequence of growing concern with the tripod ontology and more ‘individualistic’ leadership approaches, there is an emerging movement towards seeing leadership as a collaborative process, one that is co-constructed by multiple organisational actors. This newer way of thinking about leadership has been termed ‘post-heroic’ and is used to depict leadership that is more collaborative, collective-in-nature and accomplished through shared practices, interactions and relationships (Crevani et al. 2010, Fletcher 2004, Uhl-Bien 2006). As a result, leadership development and training within the NHS has broadened from a focus on individuals to now encompass groups, teams, organisations and systems (West et al. 2015).Footnote 1

This shift has also been enabled by a number of policy changes. Over the past decade, there have been a range of changes and initiatives that have influenced the way in which healthcare is organised. This includes a move towards more integrated care initiatives and partnership working between NHS organisations, local authorities and third sector organisations (NHS England 2014). Through these arrangements, hospitals are much more connected with community groups, GP practices and primary care organisations, in order to provide care that is focussed on the specific needs of a particular local population. Further policy drivers that are relevant for leadership have included the shift from competition to collaboration in order to meet the needs of increasingly complex, diverse and multifaceted patient needs, all broadly connected to the NHS Long Term Plan (NHS England 2019), which talks about the integration of services and improvements to care quality (Alderwick et al. 2019).

In the context of such policy developments , models of leadership that place an emphasis on shared practices, collaboration and joint decision making are being taken much more seriously (West et al. 2015, Willcocks and Wibberley 2015). Current leadership development approaches in the NHS have also adopted a shared/collective leadership approach with work by Storey and Holti (2013), leading to the creation of a revised behavioural healthcare leadership model. In addition, to address anticipated failings in leadership highlighted by the now-published Francis Inquiry into Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust, the NHS established a leadership academy in 2012. It was tasked with transforming healthcare culture and services by professionalising leadership and creating a more strategic approach to the development of talent across the NHS (NHS Leadership Academy [NHSLA] 2012a). In doing so, leadership development would potentially be enhanced and embedded nationally through a combined individual-team-organisation-system approach (NHSLA 2012b).

In policy literature itself, there has been much discussion and reference to the importance of developing leadership capacity across the NHS for employees at all levels of the organisational hierarchy and not just those with managerial responsibilities (NHSLA 2012b). Willcocks and Wibberley (2015) explain that one notable policy shift here involves a move towards wider stakeholders, such as doctors, being involved in leadership regardless of position. Indeed, the latter half of the twentieth century saw the emergence of a number of policy initiatives aimed at involving doctors much more systematically in the management and leadership of health services (Cogwheel Report, Ministry of Health 1967, Griffiths Report, Department of Health and Social Security 1983).

This continued into the twenty-first century, with the profession’s regulator, the General Medical Council (1993, 2003, 2009) (GMC), publishing various iterations of Tomorrow’s Doctors, its framework for the requirements of the practising doctor, which outlined not only a requirement for knowledge and understanding of organisational, medico-legal, ethical and financial issues, but also guidance relating to more ‘managerial’ and leadership aspects of healthcare provision, such as risk management and quality improvement. Calls for increased clinical leadership continued to follow (Royal College of Physicians 2005, Department of Health 2008, Academy of Medical Royal Colleges [AoMRC] and NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement [NHSI] 2010, NHSLA 2011, GMC 2012), supported by evidence that the level of engagement of an organisation with medical leaders correlated with improved outcome measures including organisational performance (National Institute for Health Research 2013, Veronesi et al. 2014, West et al. 2015).

Set against this wider context, our study explores the case for practices of healthcare leadership to shift from an individual to a collective focus through the following research question: How do collective notions of leadership support the development of leadership practices in healthcare management and leadership? In the following section we introduce one potentially useful approach for conceptualising such changes in terms of NHS leadership. The approach we introduce is referred to as ‘leadership-as-practice’ (LAP) (Carroll et al. 2008, Crevani et al. 2010, Raelin 2007).

Leadership-as-Practice

LAP has been described as a ‘new movement’ in leadership research and is concerned with the idea that leadership emerges in the ongoing flow of organisational practices (Crevani et al. 2010, Raelin 2017). LAP has its origins in social practice theory, which takes the view that social phenomena are constituted by practices, or practical orderings comprised of human, material and symbolic elements (Nicolini 2012, Reckwitz 2002, Schatzki et al. 2001). LAP theory targets leadership that emerges within the flow of those aforementioned social practices. The focus is not on the role and actions of an individual leader but on the ‘unheroic work of ordinary strategic practitioners in their day-to-day routines’ (Whittington 1996, p.734). In line with post-heroic ideals, LAP is typically collective-in-nature, having a strong discursive, interactional and relational component as practitioners connect with one another to accomplish leadership (Bolden et al. 2008, Chia and Holt 2006).

LAP scholars have also highlighted the important role of context and history in informing how leadership takes form in shared practices (Hunt and Dodge 2000, Kempster and Gregory 2017). LAP has been expounded as an especially useful ontology for conceptualising more collective and processual forms of leadership and is a fruitful area for future research (Carroll et al. 2008, Crevani et al. 2010, Kempster and Gregory 2017). At present, however, there are few documented empirical examples of leadership-as-practice, especially in healthcare work and there have been calls for more research that offers insight into leadership processes that unfold in the ‘nitty-gritty’ of everyday organisational life.

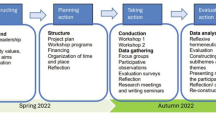

Our analysis builds upon a qualitative case study exploring a national policy initiative aiming to introduce change within UK medical curricula. Specifically, it offers insight into seven different leadership activities that comprise leadership-as-practice (Raelin 2016), which are outlined in Table 11.1. We show that whilst there are a multiplicity of examples of each of what Raelin termed the seven distinct ‘activities’,Footnote 2 at times the boundaries between these are somewhat blurred. Moreover, bringing to the fore the important role of context, culture and history in emergent collective leadership, our analysis reveals the messy, contradiction- and tension-imbued nature of such processes, which are bound up in the policy context described above.

Case and Method

This study explored micro-level practices in effecting change in UK medical education. In the 2000s, a national change initiative took place with the purpose of promoting greater leadership and management within multiple specialist medical curricula, with the ultimate aim of helping to create organisational cultures to improve services for patients across the UK (NHSI, 2010). This was intended to span all levels of medical training and was undertaken collaboratively by senior NHS stakeholders and representative organisations and associations of the medical profession.

Embracing a ‘naturalistic design’ (Lincoln and Guba 1985) as part of a qualitative research strategy and informed by Hiles’ (1999) model of disciplined inquiry, an exploratory case study approach was adopted. Hartley (2004) considers such an approach informed ‘to understand how the organizational and environmental context is having an impact on or influencing social processes’ (Hartley 2004, p.325) supporting the relevance of its use in such a context.

The second author (SM) had previously explored leadership in healthcare as part of earlier research and through this gained access to the participants who conceived, designed, managed and oversaw the implementation and development of this national policy initiative.Footnote 3 We conducted semi-structured interviews (lasting approximately 60 minutes) with 22 members of the initiative’s project team and steering group, including 13 managers and 9 doctors. By focussing on these two groups, accounts, stories and histories could be compared, notably around the impact of the project on how change was practised. Research participants were interviewed in 2012 after the project had ended and no longer had continuous ties to the initiative in question, although many did maintain existing links to the newly formed NHS Leadership Academy.Footnote 4 This study also employed analysis of historical documents. The use of documentation in case study research can offer rich, alternative insights into events that occurred as part of the case under examination (Hartley 2004). We analysed 906 pages of project plans, minutes and reports, which offered alternative explanations of the stories and narratives that arose from interviews to help in confirming or contrasting the various accounts of how the change was enacted.

However, one methodological limitation of our study is a lack of observational data, given access to the project and its participants came retrospectively. Whilst prospective data collection, allowing for observation to take place, can help strengthen any methodological approach, the diverse accounts collected via interviews, along with the documentary analysis undertaken, provided sufficient corroboration on their own, whilst acknowledging that any qualitative interpretive approach will only ever offer a version of the ‘truth’ (Bryman, 2008).

The case study employed thematic analysis, with interviews audio-recorded. Following transcription and entry into NVivo 10 (QSR International 2012), key concepts were identified and coded (Barbour 2008) by the second author (SM). ‘Provisional coding’ occurred, which involved an openness to new codes potentially emerging, in the context of evolving theoretical assumptions (Layder 1998, p. 55). The process of provisional and then open coding was abductive (Cunliffe, 2011), with leadership and organisational theories, including notably Raelin’s (2016) seven categories, the main source of a priori coding. As analysis of the transcripts progressed, in vivo/in situ codes were developed in response to the emerging themes to complement those developed from theory. For example, a concept that arose in vivo would be ‘enthusiasm’, which would become associated with the motivations individuals had for engaging with the initiative. In contrast, organisational and institutional theory literatures often discuss organisational ‘cultures’, but this manifests in different language in interviews, such as ‘getting on with others’ or ‘the way we do things around here’ and thus became a provisional code linked to an a priori concept. As Raelin’s (2016) work encompasses ‘actions’ and ‘behaviours’, any data that spoke of mindsets, mental approaches, personalities, attributes and practices became provisional codes for those concepts.

In the following section we outline the findings from the case study, utilising Raelin’s (2016) LAP framework, to elucidate how healthcare leadership embraces a collective approach.

Findings: Towards a Framework for Collective Leadership in Healthcare

Scanning

Scanning is the identification of resources, such as information or technology that can contribute to new or existing programmes through simplification or sensemaking (Raelin 2016). In the case study, project members identified resources such as previous healthcare leadership frameworks, including the NHS Leadership Qualities Framework (NHSI 2006) as well as the CanMEDS framework from Canada (Franks 2005). Furthermore, individuals drew on their understandings of the purpose of their roles, what could be considered practical interpretations of their job descriptions, to underpin their actions, for example:

I was bringing in that managerial and leadership Chief Exec experience … doing the research on shared leadership and some of the focus groups with young doctors. I did a piece of work looking at the relationship between performance and doctor engagement. What I was able to demonstrate was that there was a link that was worth exploring between the highest performing organisations and the degree of engagement of doctors. [Jacqui,Footnote 5 manager, Project Team (PT)]

Moreover, practices were informed by seminal in-profession documents that acted as a catalyst for developing leadership within the medical curriculum:

The Royal College of Physicians developed “Doctors in Society: Medical Professionalism for a Changing World” and it really clearly stated that clinical leadership was absolutely essential if doctors were to maintain and develop their sense of professionalism … [it] recognised the medical profession was in danger that if ‘we don’t do something about this, and actively demonstrate that we are making every effort to make sure we are professional, that we are safe clinically, that we’re looking for good quality outcomes, that we can regulate ourselves, then the profession’s going to be in a lot of strife’. So I guess that set the scene for a lot of what we did. [Kathryn, manager, PT]

By drawing on their job descriptions in a practical way, alongside relevant policy documents, participants were able to join these together to provide compelling motivation for the programme of work.

Signalling

Whilst scanning details the identification of resources, signalling concentrates on the mobilising and catalysing of others’ attention to a programme or project through such means as imitating, building on, modifying, ordering or synthesising prior or existing elements (Raelin 2016). Within the case study, project members convened around an agreed purpose that the project was beneficial for the profession. Participants spoke of personal motivations, as well as a wider need for it, to ensure the profession was able to best carry out its role as care givers and system leaders within the NHS. Working within a project infrastructure around that purpose, participants engaged others towards a possible future trajectory of action:

My actual contribution was getting the [Royal] Colleges and Academy [of Medical Royal Colleges] to embed these into the curricula, getting the GMC [General Medical Council] to make sure they have got them in the undergraduate curricula too. And increasing the discussions that occur in all sorts of fora about doctors and medical management and how they should be contributing more to that. [Nathan, doctor, SG]

Far from being solely heroic ‘entrepreneurs’, these individuals worked in what Lawrence and Suddaby (2006) describe as intelligent, situated action, using discursive strategies to mobilise resources, acting more in a collective or distributed manner. Drawing on their professional interests, knowledge and mutual visions,Footnote 6 project members worked with participants in reference groups,Footnote 7 adopting various simultaneous practices: advocating, defining, educating, enabling, embedding and routinising the project’s purpose through its mechanisms and practices, whilst also disassociating some of the moral foundations of arguments that had previously existed that doctors and leadership did not align (Lawrence and Suddaby 2006).

Part of this ‘signalling’ was to ensure that within the project itself, there were organisations and individuals who could act as influencers and enablers within the wider process of engagement:

We began to include one or two representatives of Colleges. There were a few occasions when other eminent people said they’d like to join the steering group and we’d have this discussion around, ‘well, if [we] say yes to [X], then we really ought to be saying that to ten other people.’ But at the same time, here’s somebody who’s got a lot of enthusiasm. And so the Vice-President of the Royal College of [organization] wanted to be involved, and we said, ‘actually to get [specialty] inside the tent on this is really important.’ [Joel, academic/senior manager, PT/SG]

Alongside this, members were able to connect the project to key events such as the consultation on the GMC’s (2009) Tomorrow’s Doctors, as a means of embedding leadership development within medical training. This is evident in project documents, such as steering group minutes, where it is noted that:

The consultation version of Tomorrow’s Doctors will include a discussion paper on leadership … GMC are planning to talk with medical schools in summer around curriculum implementation. [Steering Group Meeting minutes, 24th November 2008]

By doing so, project members were undertaking ‘scanning’ as well as ‘signalling’, aligning project activities with the external timing norms of Tomorrow’s Doctors and working with the profession towards future outcomes.

Weaving

According to Raelin (2016) ‘weaving’ describes practices or processes of creating webs of interaction across existing and new networks, by building trust between individuals and units and creating shared meanings to particular views. Our empirics demonstrated how individuals found ways to build that trust and reach shared understandings through their interactions, notably:

my world is very relational, so for me, leadership is about connecting and connectiveness and … what became clear was that the work [we] did in informing and forging relationships around leadership was starting to produce a slightly different view to challenge some of those kind of stereotypes [around doctors and management] that had existed. So the more groundswell we could get, the broader the engagement, the more we could be having those conversations, and then finding people who could have their conversations and spread the word better. [Ingrid, manager, PT]

This was also noted in project documentation, for example, the scoping study report of May 2006 (NHSI 2006, p.5):

Building relationships - The initial scoping phase of the project was specifically designed to provide time to build relationships with leaders of many of the medical professional and regulatory bodies. It also provided opportunities to meet a number of individuals with particular perspectives on, and interest and involvement in, medical management and leadership.

Furthermore, the way in which project members carried out their work was aligned to the ‘prevailing conditions’ (Moralee and Bailey, 2020) created by the existing policy context, for example High Quality Care for All (Department of Health, 2008), and the emerging workplace environment, for example Doctors in Society (Royal College of Physicians, 2005):

if we sit in our palace and don’t work with the profession, understand the profession in its context, where it’s being delivered, understand how it impacts on patients , understand the wider resource questions … [it’s] about doctors doing their jobs professionally, in whatever healthcare setting they’re working in or is created for them to work in. [Matthew, administrator, SG]

Like Raelin’s (2016) notion of ‘signalling’, these ways of working are situated in existing sets and schemas of understanding as a way of easing in the passage of new practices and ideas. This juxtaposition of ‘present’ and ‘emerging’ makes the new ideas both understandable and acceptable and identifies the potential problems and shortcomings of past practices (Lawrence and Suddaby 2006):

there is no doubt, that’s a leadership skill: listening to everybody, getting the ideas together and moving forward. That’s more the leadership that everybody should be doing as opposed to the actual leaders of the organisations … it’s embedding that type of thinking. [David, doctor, SG]

On the back of existing networks, trust between project members and other participants could be established and shared meanings created as a result.

Stabilising

The process of stabilising involves offering feedback to converge activity and evaluate effectiveness, leading to structural and behavioural changes and learning (Raelin 2016). Similar examples of shifting responsibilities away from the recognised experts (project members) and taking on board the views and perspectives of a more diverse group were evident, resulting in new learning:

[we were] very focused on what progress was being made, who we’d engaged with, what we should do with next steps … we had away days, where we would brainstorm what the framework should look like, distilling all that feedback from focus groups and a whole range of formal partnership working and committees. [Jacqui, senior manager, PT]

The project team did not consider this to be ‘one-off’ work, but iterative practices of receiving and responding to feedback:

we updated it [the competency framework] several times during the project to keep it current, using feedback that people were sending back to us to make sure that we were reflecting what was needed in the here and now and in the future. [Kathryn, manager, PT]

In particular, some of the feedback that was received focussed on the creation of language and frameworks for learning:

we had had quite a bit of feedback on it [the competency framework] so … gathering together all the different feedback and simulating that and working out ‘we can take on board this, this isn’t quite appropriate, that sort of thing’, working out who we needed, who else we needed to consult with. And then working out what language we needed to get changed, go off for a plain English review, working with the publishers, the designers to get together and [change] the look and feel of it. [Theresa, administrator, PT]

When looking at these practices more closely, it was clear that the participants coalesced around shared, collective understandings and use of words for the framework:

some of the feedback that we had was people were saying, ‘well you know this is the first time we’ve ever had a common language to know what we’re talking about, to be able to discuss leadership, because we just didn’t know what it involved before’. [Sarah, academic, PT]

It is noticeable from the excerpts above that an openness to receiving and acting on feedback helped to coalesce the various aspects of what ultimately became collective curriculum development, creating a tool with a shared language, which would ultimately lead to learning as well as structural and behavioural changes.

Inviting

Related to stabilising, inviting is the process of encouraging those who have held back to participate their ideas, energy and humanity (Raelin 2016). We found numerous examples of participation and inviting feedback, for example:

The consultation was through the reference groups … we’d present certain issues, where we’d got to and … they came back and commented on the scenarios, and made some really useful comments that, ‘you need to emphasise this more and the patient more here’. So we went back and rewrote some of the scenarios with that in mind. [Sarah, academic, PT]

This continuing participation and feedback from the reference group included ensuring individuals felt that their contribution was listened to and was worthwhile:

We had some of the junior doctors come to one of the later ones and one of them had just been on nights … the group were really good at listening and working it through, being really respectful of this poor person who had come along to this meeting, but obviously was too tired to really work out what they were saying … that again goes back to this shared leadership, so shared leadership is saying we can’t do this without everybody contributing. [Philippa, senior manager, PT]

Despite the project team being full of senior professionals with high levels of experience and expertise, it was evident that they would actively seek out and invite ideas, challenge and pushback to progress the project, for example:

So those people varied because [we] needed to have different levels of knowledge … on the undergraduate work stream we needed medical school deans or people that were involved in the education of medical students. We had medical student representatives on there as well but we also had people from the service involved in that. Then at postgraduate level we needed to have people like postgraduate deans involved in that conversation. [Kathryn, manager, PT]

What is evident here is there was a role for project members to utilise their energy to create connections to and relationships with the wider profession, integrating their collective efforts to effect change.

Unleashing

Unleashing extends the concepts of stabilising and inviting further by ensuring that everyone who wishes to contribute has a chance to, even if their contribution might create discrepancy (Raelin 2016). Project members interacted with the medical profession, encouraging broader perspectives about the role of leadership within the profession and health service, such as:

the project itself was definitely wider than the CF [competency framework]. It was more about encouraging a dialogue between doctors and managers and the system and making sure that doctors felt engaged and part of the service … recognising they had a part to play, it wasn’t just seeing patients, as important as that is, they had other things they needed to be aware of and focused on. [Theresa, project manager , PT]

This view is supported by aforementioned evidence (National Institute for Health Research 2013, Veronesi et al. 2014) that increased clinical involvement in management decision-making benefits the performance of services:

The evidence which has been accumulating over the last few years, and the gut feeling prior to that very much was, if doctors are close to the decision making processes, either making them or certainly buying into the decisions made by management structures, then you get a more efficient organisation, you get better morale amongst the staff and you get better patient outcomes at the end of the day. It’s a win-win situation. [Nathan, doctor, SG]

The involvement of doctors in management and leadership continues to be a contested area (Davies and Harrison, 2019), with differing views informing the developing of this field, and it is through processes such as unleashing, as indicated here, that strategy can be debated and informed and result in a better understanding of how leadership might be practised.

Reflecting

Finally, reflecting is the process of triggering thoughtfulness within self and others to ponder the meaning of past, current and future experiences and to learn how to meet mutual needs and interests (Raelin 2016). There were several examples of informal reflection processes that practitioners participated in:

usually it was quite pragmatic in terms of [having] further discussions about this, or another meeting. Sometimes it was just asking for advice, … but at the same time just trying to make links and understand, because maybe you had a conversation with somebody and they were working on something that was semi-related to one of the other workstreams. And sometimes that would only happen at the meeting because it was, ‘oh you met with so and so, I met with so and so, oh they didn’t mention they were meeting you.’ So it was that sort of, more knowledge sharing I think, more than anything. [Theresa, administrator, PT]

Furthermore, there were examples of how the approach to the change initiative had engendered wide reaching reflections about the purpose of the project:

this is much more about encouraging doctors to reflect on what they need to know about management and their leadership behaviours … about the extent to which doctors need to understand the resource implications of their decisions … [now], the focus of medicine is doing the best for your patient , almost irrespective of cost. But I, with my taxpayer hat on, perhaps question that. [Matthew, administrator, SG]

Learning through collective reflection has been identified as a valuable form of learning at work, with reflective dialogue helping staff to function more effectively within their daily work practice. Research has also identified that staff value connecting and sharing knowledge with others, and that dialogue with more experienced colleagues and peers provides rich learning opportunities (Ipe 2003).

Leadership Development in Healthcare: Proposals for Practice and Research

Accomplishing Leadership Together

Our analysis offers insight into the practices of the seven co-constructed LAP activities (Raelin 2016). Considered holistically, we observe how in each of the LAP activities, participants from the study combined their knowledge and through their spontaneous collaboration and shared understandings accomplished leadership together (Gronn 2002).

We also see how many of the activities have a clear future focus, which is what depicts the practices as ‘leadership’ as opposed to organisational routines or simply ‘organising’. In our case, the practitioners often had a shared purpose working towards a possible future trajectory of action (Drath et al., 2008). The seven activities facilitated a shared conception of what their work was aimed towards, subsequently mobilising a sense of collective intentionality, which Crevani et al. (2010, p.81) describe as ‘co-construction of a sense of common direction in social interaction’.

Whilst the analysis offered above provides insight into each of the seven LAP activities separately, in the ongoing flux of daily practices, many of the practices interrelated. They were not discrete or distinct, but intricate, interconnected parts of a web of LAP. For example, when engaged in the practice of ‘signalling’, the practitioners in the case study also drew heavily on resources such as the competency framework (‘scanning’) in order to achieve the desired objectives.

Culture, Context and History

The emergence and unfolding of these interrelated practices were also informed by the culture, context and history of the empirical setting. The history of the division of work in healthcare, for example, traditionally impacts on the types of activities practitioners are ‘invited’ to participate in, as well as the themes of the ‘reflective’ conversations that the practitioners were involved in. Such historical factors are examples of ‘antecedent influences’ (Kempster and Parry, 2018) that act as a stimulus for leadership processes (Drath et al. 2008), yet within this case, we can begin to see an openness and ‘levelling up’ of hierarchies and voices. Moreover, the organisation and structure of the project, to hold multiple, diverse forums and meetings with individuals from all medical career grades, as well as the ways in which the project team, between themselves, and in their dialogue with the steering group, created a cultural and contextual norm, facilitated the LAP activity of ‘reflection’.

Culture, context and history are often, however, the source of tensions and challenges within collective practice. In this respect, our analysis of the data revealed that whilst much of the activity of LAP was productive, constructive and purposeful, it was not without tension and conflict. When unpacking the practice of ‘unleashing’, for example, the data illustrated some of the power plays that pervade professional healthcare work, with some practitioners’ involvement and contribution being thwarted. Critiques of LAP theory focus on its neglect of issues of power and asymmetry and how the idea of shared, collaborative and collective approaches to accomplishing leadership downplay embedded and inherent power relations that can arise as people ‘do’ leadership with others (Collinson 2018). In the NHS, professionals such as those discussed in this chapter are, in their practices, frequently navigating and negotiating complex and situated power dynamics, many of which are entrenched in longstanding professional ideology and expertise, as well as role- and boundary-related battles and tensions.

Future research needs to explore the subtle, yet pervasive, ways in which power impinges upon leadership-as-practice in healthcare work. Our research also highlights the interrelatedness of practices and their historical and contextual influences, thereby offering a more nuanced understanding of LAP in healthcare work. In this respect, future research could explore the subtle ways that context and history impinge upon contemporary leadership practices.

Implications for Leadership and Policy

This analysis questions the current conceptualisation and direction of travel. Traditional approaches to leadership development, such as in the NHS, focus largely on addressing the individual deficit in attributes/competencies which can be ‘fixed’ through leader development, such as the NHS Leadership Qualities Framework (2006), and subsequently the NHS Leadership Framework (2011). Such an ‘understanding’ comes from classic bureaucracies of the industrial age with ordered roles, compartmentalised functions and, still evident within the NHS, aforementioned hierarchical structures. Moreover, with leadership assumed to make a special, significant and positive contribution, leaders are therefore accorded the privilege of framing followers’ reality, resulting in a romance and charisma of leadership which spreads the mythology of leader invincibility (Crevani et al. 2010, Raelin 2011, 2016). This further promulgates a pro-active and visionary archetype (akin to transformational leadership) of professional development for the ‘heroic’, individual leader.

Critics of this focus (MacGillivray 2018, O’Reilly and Reed 2011) describe how modern, complex work activity is organised around teams and groups within organisations and systems, not individuals, and provide a much-needed shift in discourse and rhetoric in policy literature away from the idea of leaders as heroes and leadership as an individual phenomenon. A typical focus on heroic/charismatic leaders can result in a lack of innovation and in professional service organisations, like healthcare, there is increasingly hybridisation of managerial and professional approaches. The policy discourse for public services uses a language of competition, survival, progress, as well as moral and intellectual pre-eminence, rather than the wisdom of the crowd and these approaches have failed to crystallise how public services may be transformed.

Our argument promotes leadership policy that accounts for practice and collective notions, which will help to create frameworks that foster more practice-based approaches. Such frameworks and models that are not individualistic in focus and do not just focus on individual qualities will emphasise how leadership is something that is enacted by multiple individuals and can be shared amongst people in a team at all levels of the organisational hierarchy.

Towards Shared and Collective Leadership in Practice

Indeed, concepts such as shared, collective and distributed leadership (Crevani et al. 2010, Storey and Holti 2013) have begun to reframe leadership in the delivery of healthcare services as more of a dynamic, situated, dialectic and negotiated activity (Raelin 2016) amongst multiple professional, as well as occupational, actors, which is supported by the examples in the case here. As Raelin (2016, p.7) attests, knowledge arises ‘from a contested interaction among a community of inquirers [healthcare professionals] rather than a single source of expertise’. In their ongoing practices these individuals are collectively informing the routines, actions and habits of their teams, groups, departments or organisations. In view of this, there needs to be a much stronger policy movement towards shared, practice-based approaches if we are to see improvement in leadership within health services.

Leader and leadership development in the NHS needs to consider how to reframe and reinvigorate its approach towards flows of leadership practice in dynamic and situated activity, focussing more on existing strengths and skills and on ‘problem identification’ as a collective. This may include a greater emphasis on collective workplace-based learning and less on addressing individual weaknesses in terms of their leadership competency. Consideration of more critical leadership approaches and positions that focus on the problem, not the individual as a deficit to be corrected, may require policy makers to adopt a more patient- and person-centred approach, with greater emphasis on the specific local and national ‘problems’ within healthcare, rather than seeking to be seen to ‘do something’ through well-intended leader development solutions. With the creation of Primary Care Networks and Integrated Care Systems, policy has begun its journey to respond to these challenges (NHS England 2014).

In the context of scandals like Mid Staffordshire (Francis 2013) and Morecambe Bay (Kirkup 2015), both of which called for a change in culture due to a failure of leadership (Smith and Chambers 2019), shifting, or, in some cases, extending, investment to creating cultures, environments and spaces that foster collaboration, co-operation, shared reflection, working together and joint decision making— as espoused by the LAP activities highlighted in this case—could consign poor leadership cultures to the past, by enabling leadership training and development that enacts the rhetoric of valuing everyone’s knowledge and input (including other less ‘heroic’ professional groups alongside patients).

For professional groups (who make up a large proportion of healthcare staff), this will require curriculum developers, heads of service and the professional groups themselves, as well as individual practitioners, to become versed with operating two potentially competing mental models: one that comes from innate, professional-scientific and individualised training and these alternative co-constructed leadership-as-practice activities. In doing so, there may need to be a shift away from a focus on ‘biomedical’ and technical models of training and development to more nuanced, situation-based, collective approaches.

Notes

- 1.

Much of this has come about as a result of the Francis Inquiry (2013) into care at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust, which placed importance on the need for better, more inclusive and effective leadership given its conclusion of ‘a dangerous culture and weak leadership’ (King’s Fund 2013, p.3) at the Trust.

- 2.

In much of the literature on practice approaches, different authors use the terms ‘practice’ and ‘activity’ interchangeably. In our study we use the term ‘practice’ when descripting an overall leadership approach or leadership in a more general sense. We align with Raelin’s use of the term ‘activity’ to describe specific leadership undertakings within practice more generally.

- 3.

The study was bound by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Research Ethics Framework and received ethical approval from De Montfort University at the time of formal registration and acceptance onto the second author’s doctoral programme in June 2011.

- 4.

Interviews covered the following topics: job role; self/others’ involvement; people not involved/not invited; motivation for involvement; practices, actions, activities they undertook; approaches to role: self/others; role/position in relation to organisation’s role; key relationships: people, organisations; typicality (or not) of groups; particular/notable/memorable incidents, for example tensions, agreements, tipping points; the resulting outcome; outcomes relevant to the participant/unofficial outcomes, that is, benefits, legacies, and so on; impact without participant/organisation’s involvement; current developments/latest thoughts.

- 5.

All of the participants’ names have been replaced by pseudonyms.

- 6.

Interests which encompassed clinical leadership; succession planning; career development; renewing the psychological contract between what was expected of doctors and the public.

- 7.

Groups of doctors at various career stages who were invited to comment on and develop the competency framework.

References

Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2010). Medical Leadership Competency Framework: Enhancing Engagement in Medical Leadership, 3rd edition, July.

Barbour, R. (2008). Introducing qualitative research: A Student's guide to the craft of doing qualitative research. Sage.

Bolden, R., Petrov, G., & Gosling, J. (2008). Developing collective leadership in higher education: Final report. Leadership Foundation for Higher Education.

Bryman, A. (2008). Social research methods (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Carroll, B., Levy, L., & Richmond, D. (2008). Leadership as practice: Challenging the competency paradigm. Leadership, 4(4), 363–379.

Chia, R., & Holt, R. (2006). Strategy as practical coping: A Heideggerian perspective. Organization Studies, 27(5), 635–655.

Collinson, M. (2018). So what is new about leadership-as-practice? Leadership, 14(3), 384–390.

Crevani, L., Lindgren, M., & Packendorff, J. (2010). Leadership, not leaders: On the study of leadership as practices and interactions. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 26, 77–86.

Cunliffe, A. L. (2011). Crafting qualitative research: Morgan and Smircich 30 years on. Organizational Research Methods, 14(4), 647–673.

Department of Health and Social Security. (1983). NHS Management Inquiry (Griffiths report). HMSO.

Department of Health. (2008). High Quality Care for All: NHS Next Stage Review Final Report. (Darzi Report), CM 7432, June. TSO: Norwich.

Drath, W. H., McCauley, C. D., Palus, C. J., Van Velsor, E., O'Connor, P. M., & McGuire, J. B. (2008). Direction, alignment, commitment: Toward a more integrative ontology of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(6), 635–653.

Fletcher, J. K. (2004). The paradox of post heroic leadership: An essay on gender, power, and transformational change. The Leadership Quarterly, 15, 647–661.

Francis, R. (2013). Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. HC 947, February, Norwich: TSO.

General Medical Council. (1993). Tomorrow’s doctors: Recommendations on undergraduate medical education. General Medical Council.

General Medical Council. (2003). Tomorrow’s doctors. General Medical Council.

General Medical Council. (2009). Tomorrow’s doctors. General Medical Council.

Gronn, P. (2002). Distributed leadership as a unit of analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(4), 423–451.

Hartley, J. (2004). Case study research. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research (pp. 323–333). Sage.

Hiles, D. (1999). Paradigms Lost – Paradigms Regained, a summary of the paper presented to the 18th International Human Science Research Conference, Sheffield, UK, July 26–29.

House, R., Javidan, M., Hanges, P., & Dorfman, P. (2002). Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: An introduction to project GLOBE. Journal of World Business, 37, 3–10.

Hunt, J. G., & Dodge, G. E. (2000). Leadership déjà vu all over again. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(4), 435–458.

Ipe, M. (2003). Knowledge sharing in organizations: A conceptual framework. Human Resource Development Review, 2(4), 337–359.

Kempster, S., & Gregory, S. H. (2017). ‘Should I stay or should I go?’ Exploring leadership-as-practice in the middle management role. Leadership, 13(4), 496–515.

Kempster, S., & Parry, K. (2018). After leaders: A world of leading and leadership … with no leaders. In B. Carroll, J. Firth, & S. Wilson (Eds.), After Leadership (1st ed.). Routledge.

King’s Fund. (2013). Patient-centred leadership: Rediscovering our purpose. King’s Fund.

Kirkup, B. (2015). The Report of the Morecambe Bay Investigation: An independent investigation into the management, delivery and outcomes of care provided by the maternity and neonatal services at the University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS Foundation Trust from January 2004 to June 2013. March.

Lawrence, T. B., & Suddaby, R. (2006). Institutions and institutional work. In S. R. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. B. Lawrence, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Handbook of organization studies (2nd ed., pp. 215–254). Sage.

Layder, D. (1998). Sociological practice: Linking theory and social research. Sage.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

MacGillivray, E. (2018). Leadership as practice meets knowledge as flow: Emerging perspectives for leaders in knowledge-intensive organizations. Journal of Public Affairs, 18, e1699.

Ministry of Health. (1967). First report of the joint working party on the organisation of medical work in hospitals. HMSO (Cogwheel Report).

Moralee, S., & Bailey, S. (2020). Beyond hybridity in organized professionalism: A case study of medical curriculum change. In P. Nugus et al. (Eds.), Transitions and boundaries in the coordination and reform of health services: Building knowledge, strategy and leadership (pp. 167–192). Palgrave Macmillan.

NHS England. (2014). Five Year Forward View. October.

NHS England. (2019). Long Term Plan. January.

National Institute for Health Research (2013). New Evidence on Management and Leadership. Health Services and Delivery Research Programme, December, Southampton: HS&DR Programme.

NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (2006). Improving the effectiveness of health services: The importance of generating greater Medical Engagement in leadership. May. Coventry: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement.

NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. (2010). Enhancing engagement in medical leadership 2009/10 project plan. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement.

NHS Leadership Academy. (2011). Leadership framework: A summary. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement.

NHS Leadership Academy. (2012a). National centre of excellence for NHS leaders opens.

NHS Leadership Academy. (2012b). Introduction to the NHS Leadership Academy Core Programmes.

Nicolini, D. (2012). Practice theory, work and organization: An introduction. Oxford University Press.

O’Reilly, D., & Reed, M. (2011). The grit in the oyster: Professionalism, managerialism and Leaderism as discourses of UK public services modernization. Organization Studies, 32(8), 1079–1101.

Pearce, C. L., & Manz, C. C. (2005). The new silver bullets of leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 34(2), 130–140.

Raelin, J. A. (2007). Towards an epistemology of practice. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 6(4), 495–519.

Raelin, J. (2011). From leadership-as-practice to leaderful practice. Leadership, 7(2), 195–211.

Raelin, J. A. (Ed.). (2016). Leadership-as-practice: Theory and application. Routledge.

Raelin, J. A. (2017). Leadership-as-practice: Theory and application - an editor’s reflection. Leadership, 13(2), 215–221.

Reckwitz, A. (2002). Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. European Journal of Social Theory, 5(2), 243–263.

Royal College of Physicians. (2005). Doctors in society: Medical professionalism in a changing world. Report of a Working Party, December. London: RCP.

Schatzki, T. R., Knorr-Cetina, K., & von Savigny, E. (2001). The practice turn in contemporary theory. Routledge.

Smith, J., & Chambers, N. (2019). Mid Staffordshire: A case study of failed governance and leadership? The Political Quarterly, 90(2), 194–209.

Storey, J., & Holti, R. (2013). Towards a New Model of Leadership for the NHS. NHS Leadership Academy.

Uhl-Bien, M. (2006). Relational leadership theory: Exploring the social processes of leadership and organizing. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 654–676.

Veronesi, G., Kirkpatrick, I., & Vallascas, F. (2014). Does clinical management improve efficiency? Evidence from the English National Health Service. Public Money & Management, 34(1), 35–42.

Whittington, R. (1996). Strategy as practice. Long Range Planning, 29(5), 731–735.

West, M., Loewenthal, L., Armit, K., Eckert, R., West, T., & Lee, A. (2015). Leadership and leadership development in health care: The evidence base. Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management.

Willcocks, S. G., & Wibberley, G. (2015). Exploring a shared leadership perspective for NHS doctors. Leadership in Health Services, 28(4), 345–355.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Willocks, K., Moralee, S. (2021). Reframing Healthcare Leadership: From Individualism to Leadership as Collective Practice. In: Kislov, R., Burns, D., Mørk, B.E., Montgomery, K. (eds) Managing Healthcare Organisations in Challenging Policy Contexts. Organizational Behaviour in Healthcare. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81093-1_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81093-1_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-81092-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-81093-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)