Abstract

Addictions are among the leading causes of preventable death worldwide and in the United States. Given the morbidity and mortality of alcohol and other substance use disorders, effective treatments are needed. A recent meta-analysis found participation in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) to be as effective – if not more effective – than other forms of alcohol use disorder treatment. Moreover, the methods used by clinicians to facilitate active AA and other twelve-step (TS) engagement (e.g., twelve-step facilitation, TSF) have been shown to increase the likelihood that individuals struggling with addictions will actively participate in twelve-step groups.

The authors of this chapter are clinicians who treat patients who struggle with various addictions and co-occurring mental health disorders. We write this chapter to explain why twelve-step participation is a vital treatment component for many, but not all, who are seeking spiritual renewal and recovery. Our aim is to offer hope that recovery from addiction is possible and that patients with a Christian worldview can find a group that supports recovery and their Christian faith. We will briefly review the intersection of twelve-step spirituality and Christianity by examining the historical background and Christian origins of AA/TS/TSF, examine putative mechanisms that promote recovery from addictions, compare and contrast some twelve-step self-help recovery groups, provide a case example, examine the expansion of peer-led mutual help groups, and close with future directions.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Addiction

- Alcohol use disorder

- Twelve-step groups

- Twelve-step facilitation

- Alcoholics Anonymous

- Christianity

- Secular-mutual help groups

The Intersection of Christianity and Twelve-Step Spirituality

God give me the serenity to accept things which cannot be changed;

Give me courage to change things which must be changed;

And the wisdom to distinguish one from the other. [1]

Alcohol and other substance use disorders are among leading causes of preventable death worldwide [2]. On a given day in the United States of America, an estimated 128 persons will die from opioid overdose, 241 will die from alcohol-related disease, and 1,315 will die from cigarette smoking-related illnesses [3]. Societal costs of substance use are estimated to exceed $740 billion each year [4]. These statistics do not convey the untold pain and suffering endured by persons with substance use disorders, their families, friends, and neighbors.

Given the societal impact of alcohol and other substance use disorders, effective treatments are desperately needed. A recent meta-analysis found that participation in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is as effective as – if not more effective than – other treatments of alcohol use disorders [5]. And active engagement strategies used by clinicians to facilitate active AA and other twelve-step (TS) engagement (i.e., twelve-step facilitation, TSF) are believed to increase the likelihood of persons with alcohol use disorders and other individuals struggling with other addictions to actively participate in twelve-step groups [6].

Of note, while terms like “alcoholic” and “substance abuser” remain common parlance in AA/TSF, recent research suggests that use of these terms may promote attitudes of dismissiveness and condemnation (i.e., stigma) toward persons who struggle with problematic alcohol/substance use and reduce access to treatment resources. Therefore, throughout this chapter, we will favor the use of more modern terminology (e.g., “persons with an alcohol use disorder” and “persons with a substance use disorder”) [7].

Three key principles undergird the healing process that occurs with twelve-step self-help recovery groups and TSF: (1) acceptance, (2) surrender, and (3) active involvement in twelve-step meetings and related activities [6].

The authors of this chapter are clinicians who treat patients who struggle with various addictions and co-occurring mental health disorders. We write this chapter to explain why TS participation may be an important component of treatment for many, but not all, persons who are seeking spiritual renewal and recovery. We will briefly review the intersection of TS spirituality and Christianity, to examine the historical background and Christian origins of AA/TS/TSF; review putative mechanisms that promote recovery from addictions; compare and contrast some TS self-help recovery groups and TSF; provide case examples; examine the expansion of peer-led mutual help groups, including secular support groups; and close with future directions.

Christian Origins of Alcoholics Anonymous

AA/TS/TSF is rooted in both secular and religious traditions. The Hebrew Bible, which comprises the bulk of Christian sacred scriptures, is replete with warnings against various forms of vice and excess, including heavy alcohol use, though exceptions were made for moderate and/or occasional drinking (e.g., “Alcohol is for the dying, and wine for those in bitter distress” [Proverbs 31:6]). In Scripture alcohol is first introduced in the story of Noah, who personifies the paradox of alcohol as a means of escape (e.g., from unbearable realities) but also as a source of trauma for its user and those closest to him when consumed in excess.

Alcohol is also explicitly addressed in the Christian New Testament: Christ’s first miracle was turning water into wine; the sacred ritual of communion – instituted for the church at the Last Supper prior to Christ’s crucifixion – entails regular, intermittent consumption of small portions of wine; early Christians filled with the Holy Spirit at the Jewish feast of Pentecost were ridiculed for supposed intoxication [8]. The Apostle Paul minces no words in his epistle to the ancient Greek seaport city of Corinth: “[None] who are addicted to hard drinking… will inherit God’s Kingdom” [1 Cor 6:10 Weymouth New Testament]. As Christianity spread throughout the globe to become a dominant worldview in the centuries following, such views on alcohol became increasingly commonplace [9].

For Western society in the modern era, the novel distillation techniques and industrialization facilitated the widespread consumption of high-proof alcohol. As profound societal consequences ensued, some called for moderation in drinking, while others advocated complete abstinence. From 1920 to 1933, the sale of alcohol was legally prohibited in the United States. Despite such far-reaching legal measures, alcoholism use remained widespread.

Modern medicine was not exempt from the effects of alcohol and substance use. The introduction of the hypodermic needle and the mass production of cigarettes increased the addictive potential of opioid and tobacco, respectively. The Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), who founded the discipline of psychoanalysis, proposed – based on personal experience – that opioid addiction could be relieved by cocaine, only to find himself trading one addiction for another [10, 11]. The Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung (1975–1961), seemingly acknowledging the relentless grip that alcoholism had on individuals, told a wealthy American patient that his case was hopeless absent religious conversion [12].

On Mother’s Day, 1935, Henrietta Seiberling, a wealthy college-educated woman from Akron, OH (USA), encouraged two men whom she was hosting in her home to have hope that Christian faith could help promote their recovery from severe alcohol addiction. Seiberling was a leader in the local branch of the Oxford Group, an evangelical movement founded by Frank Buchman, a convert of revival services held in Keswick, England. After his conversion, Buchman sought to return to “first-century Christianity,” de-emphasizing hierarchy, doctrine, grand edifices, and other trappings of formalized religion. Seiberling devoted herself to praying for her guests’ recovery. She met with them regularly to discuss the importance of private prayer, anonymity, avoidance of external funding sources, and total reliance on God. Over several months, other alcoholics were invited to attend these meetings of the “alcoholic squad of the Oxford Group,” which later became known as Alcoholics Anonymous [13].Footnote 1

For one of Seiberling’s early guests, William G. Wilson (“Bill W.”), this experience was not his first encounter with evangelical Christianity. Though previously averse to religion, Wilson had a year earlier heeded a friend’s advice to begin attending local meetings of the Oxford Group in New York City led by Episcopalian pastor Sam Shoemaker, who emphasized the importance of introspection, admission of flaws in one’s character, and seeking to make amends for past harms done to others. Soon after attending his first Oxford Group meeting, Wilson resumed heavy drinking and fell severely ill. Though still averse to religion, Wilson cried out from his hospital bed, “If there is a God, let Him show Himself!” Wilson then recalled experiencing a sensation of ecstasy followed by profound tranquility: “Now for a time I was in another world, a new world of consciousness… a wonderful feeling of Presence.” Wilson would wrestle with intense cravings following this experience – which ultimately led his reaching out through Oxford Group contacts to Seiberling for support – but he never drank again.

Seiberling’s other guest, a surgeon named Robert H. Smith (“Dr. Bob”), also met Seiberling after he began attending the Oxford Group. Dr. Smith was introduced to the Oxford Group by his wife, Anne Smith, who had earlier attended a lecture given by Buchman. Dr. Smith nonetheless continued to drink for 2 years until Seiberling introduced him to Wilson in 1935. In contrast to Wilson’s tendencies toward externalizing behaviors and social drinking, Smith was introverted and drank alone. Despite their differing temperaments, Wilson teamed up with Smith to try different methods to promote recovery from alcohol use disorder (or, “alcoholism,” as it was then called).

Smith’s professional experience as a physician – combined with Wilson’s personal encounters as a patient – doubtless contributed to the development of AA’s traditions. Several years prior to his hospital bed epiphany, Wilson had been treated by a New York City medical doctor (Dr. William D. Silkworth) who regarded “alcoholism” as a disease (i.e., a physical allergy), a view which contrasted sharply with the then-prevailing societal view of the condition as a form of moral failure. At the time, hospitals barred admission of “drunks”; yet with the assistance of a Catholic nun (Bridget D. M. Gavin, or “Sister Mary Ignatia”) assigned by her church to serve as the admissions gatekeeper at Akron hospital, Smith began admitting persons to the hospital for “gastritis” as a cover to provide medical treatment.

AA’s organizational tenets became accessible to a wider audience after Wilson published a book entitled Alcoholics Anonymous in 1939. The Big Book, as it soon came to be called, featured “12 steps” drawn from various Christian traditions, especially those of the Oxford Group [14, 15]:

-

1.

We admitted we were powerless over alcohol – that our lives had become unmanageable.

-

2.

Came to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

-

3.

Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.

-

4.

Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

-

5.

Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

-

6.

Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.

-

7.

Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.

-

8.

Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all.

-

9.

Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

-

10.

Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.

-

11.

Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God, as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.

-

12.

Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs.

Thus, with minimal reference to modern medicine, psychology, or psychiatry (though Wilson did later credit Jung and Silkworth for their contributions to AA), the 12 steps were laden with unmistakably religiously themes. They explicitly referenced traditional elements of Christianity, “God,” “prayer”/”praying,” “meditation,” “His will,” and “spiritual awakening,” but made more guarded reference to others: sins (“wrongs,” “shortcomings,” “defects of character”), confession (“admitted to God…”), self-examination (“take personal inventory”), submission (“turn our will… over to the care of God”), restitution (“making amends”), and evangelism (“carry this message to alcoholics”). Still, some of the 12 steps were ambiguous and open to personal interpretation. The phrase “God as we understood Him,” while also originating in the Oxford movement to refer to persons in various stages of spiritual maturation, created ambiguity as to which deity (if any) this “higher power” referred.

Wilson recognized and even embraced this ambiguity. He saw an expanded interpretation of the deity (e.g., viewing “the AA group” as the higher power) as a means to broaden AA’s appeal and reach to more individuals with alcoholism. Personally, he dabbled with non-Christian religious experiences (spiritualism) and even the use of nonalcoholic substances (LSD). For Wilson and other AA participants, God seemed to be more the means to the end (sobriety) than an end in and of itself. This inclusive view of deity did indeed enhance AA’s reception among nonreligious persons, but was met with mixed reviews by the Christian community at large [13, 16].

Nonetheless, in the decades since its founding, AA expanded to include over 2 million members worldwide, many of whom credit AA and the 12 steps for their sustained recovery from alcoholism. Offshoots of AA and the 12 steps now include organizations supporting partners of persons with alcoholics (Al-Anon), adult children of alcoholics, as well as persons struggling with drug use (e.g., Narcotics Anonymous, or NA), gambling, sexual compulsions, and other problematic behaviors.

Case 1: Finding Recovery Through the 12 Steps

Eric got his first buzz at the age of seven at a family gathering when a mischievous cousin laced his drink with alcohol as a prank. Abandoned by his father not long thereafter, his mother tried her best to raise Eric in the Christian faith, taking him to weekly church services and having him commit scripture to memory. Eric excelled academically and was known for his caring, endearing demeanor. But throughout his youth, Eric found himself hounded by the pain of his father’s absence and urges to relive his childhood high. In his late teens, he succumbed to these cravings, experimenting with cocaine and other drugs. For the next few years, Eric found himself increasingly dependent to drugs and especially alcohol, cycling through a series of rehab treatment programs, each of which he found ineffective, in large part due to the ready availability of substances within the “treatment” programs.

By his mid-twenties, Eric was married, father to a young child, and struggling to hold onto a job due to his heavy alcohol use. Heeding the counsel of pastor and family, Eric started in an over yearlong faith-based residential program called Teen Challenge. Eric found that this program’s strict visitor policy separated him from his wife and child; however, so after just a few weeks with Teen Challenge, he switched to another residential program across town sponsored by the Salvation Army. The Salvation Army program had a more relaxed visitor policy, hosting in-house church services each Sunday followed by a dinner prepared by staff for residents and visiting family members. During the week, residents would attend local twelve-step program meetings. Eric established a relationship with a sponsor and started “working the steps” while in the Salvation Army residential program. Upon completing the program, he moved back to live with family but continued his involvement with the 12 steps, attending local Alcoholics Anonymous meetings on a daily (and on particularly challenging days even twice daily) basis, which allowed him to achieve several years of continuous sobriety by his late 30s. Continued below

Outcomes and Mechanisms Common to Twelve-Step Recovery Groups

A growing body of literature has examined the mechanisms and effectiveness of AA/TS/TSF. A 2020 Cochrane meta-analysis of 27 studies, with 10,565 participants, found robust evidence that AA is as effective – and possibly more effective – in promoting long-term abstinence from alcohol in comparison with other standardized treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy and motivational interviewing [5]. At the same time, the Cochrane study showed that AA attendance was associated with significant healthcare cost savings compared to other treatments. Furthermore, evidence for TSF in treating alcohol use disorder is robust and well established [6], and preliminary findings are promising for the effectiveness for TS and TSF for other types of addiction, including stimulants and opiates [6].

Why and How Do AA, TS, and TSF Work?

Three key principles are often thought to be central to the effectiveness of TS and TSF:

-

1.

Acceptance that drug addiction is a chronic and often recurrent disease that often becomes unmanageable, and that willpower alone is insufficient to achieve abstinence and recovery

-

2.

Surrender that requires the individual giving up control to a higher power or authority and accepting fellowship and support from others in recovery

-

3.

Active and sustained involvement in twelve-step group meetings, and related activities including working with a sponsor [6]

But what are the mechanisms by which these produce positive outcomes? And to what extent does spirituality – and particularly Christianity – play a role?

TS/TSF clinical research has focused on three active ingredients: spirituality, cognitive shifts, and psychological variables [17].Footnote 2

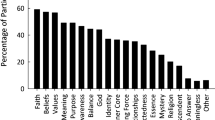

Spirituality

Spirituality has been variously defined, but generally refers to one’s relationship to something larger than the self which gives life meaning2. Peteet has suggested that twelve-step programs address the spiritual needs of addicted individuals in the domains of identity, integrity, an inner life, and interdependence [18]. For example, each speaker at a meeting acknowledges his identity by stating: “Hello, my name is ___, and I am an alcoholic (addict).” AA members emphasize that the program is “spiritual, not religious,” and point out that persons who do not identify as spiritual or religious (e.g., self-professing atheists) can benefit from AA just as much as those who identify as spiritual or religious. However, atheists are more likely to be comfortable with a secular, science-based approach, and less likely to accept referrals to AA and attend meetings than persons who are open to religion. (See the section below, “Finding the Right Mutual Help Group for Your Patient” for additional information on secular groups.) (Fig. 11.1).

Persons who are less religious are less likely to attend AA meetings. On the other hand, clinicians are more likely to refer patients who are religious to AA. Still, patients who attend AA experience an increase in religiosity, regardless of their baseline level of religiosity [19]

Regardless of initial beliefs or worldviews, however, research has shown that patients who attend AA meetings regularly experience an increase in their level of religious belief (religiosity), which parallels decreases in alcohol consumption [19].

What Does Involvement in AA Consist Of?

Surveys of AA members have identified active ingredients of behavior change including the following [17, 20]:

-

“Working the steps”

-

Reading AA core literature

-

Telling one’s story at an AA meeting

-

Having a sponsor/sponsorship

Given the religious connotations of the first two, it is not surprising that many continue to regard spirituality as an essential ingredient in AA’s recipe for personal growth and change.

Partly in reaction to the spiritual emphasis of AA, there has been in recent decades a proliferation of explicitly non-spiritually oriented recovery groups, such as SMART Recovery. Comparative effectiveness research examining differences among these approaches is complicated by several confounds: many individuals who attend nonreligious recovery groups also attend AA, and recovery groups are by their very nature anonymous. Further research is needed to compare these contrasting approaches while controlling for such potential confounders.

Cognitive Shifts

The 12th step refers to a “spiritual awakening.” AA literature notes that “with few exceptions, our members find that they have tapped an unsuspected inner resource, which they presently identify with their own conception of a Power greater than themselves” (pp. 569–570). Twelve step-oriented therapists seek to promote cognitive shifts throughout the course of treatment, such as considering oneself powerless over alcohol. Other examples of cognitive shifts promoted in AA include cognitive deflation (e.g., recognition of one’s own faults and powerlessness over alcohol), and increased sense of self-efficacy (e.g., through reliance on “God”), and even improved cognitive functioning with long-term abstinence.

Still, other therapies (e.g., CBT) seek to promote cognitive shifts and reframing. Why would AA/TSF be superior to CBT in Project MATCH and other research if the main mechanism for change was the promotion of cognitive shifts? Could it be that the cognitive shifts put in motion by AA are different than those affected by CBT?

Psychological Factors

Changes in impulsivity, attachment, empathy, and depression have all been proposed as psychological variables mediating the changes in drinking patterns which AA affects. Kelly hypothesized that depression and alcohol use have a bidirectional relationship and that AA attendance serves as a form of behavioral activation, breaking the loop of alcohol contributing to depression and its contribution to alcohol use [21] (Fig. 11.2).

Kelly proposed that AA attendance and involvement reduces alcohol use, which in turn leads to reduced depressive symptoms. Decreased depressive symptoms would then further reduce alcohol use [21]

At the same time, one might wonder if there is more to the story in terms of mediating variables, particularly considering that continuing AA attendance is associated with increased religiosity.

Christian-Based Twelve-Step Recovery Groups: How Are They Different from Other TS/TSF?

Undoubtedly, there are twelve-step recovery groups without a Christian worldview where Christians achieve abstinence and recovery, likely due to the fundamental processes and mechanisms described in the previous section. Does Christianity add to the mix of factors that lead to recovery, and if so, how? One particular Christian-based recovery group, Celebrate Recovery, has begun to address these questions.

What Is Celebrate Recovery (CR)?

Celebrate Recovery is an explicitly Christian-based recovery support organization, in which CR groups function under the auspices of specific churches. The CR website states that over five million individuals have participated in a CR step study and over 35,000 churches sponsor CR recovery groups. CR was co-founded in 1991 by John Baker and Rick Warren, leaders and members of Saddleback Church, Lake Forest, California. The onus for creating CR grew out of John’s discomfort in expressing Christian beliefs within Alcoholics Anonymous meetings that he attended. Baker’s goal, with encouragement from leadership at Saddleback Church, was to create a new type of mutual-support group where he and like-minded attendees could celebrate their recovery from addiction and problematic behaviors, by benefitting not only from the healing process that occur with twelve-step membership but also from the healing and growth that can occur when recovery efforts and behavior are reinforced by worship experiences and candid discussion with fellow believers who share similar Christian values and worldview.

How Is CR Different from Other Twelve-Step Recovery Groups?

CR principles include twelve-step principles common to all AA/TS groups, described previously. These 12 steps are augmented by eight recovery principles based on the beatitudes found in the Gospel of Matthew 5:1–12. According to the CR website [22], these recovery principles provide a “road to recovery” that is based on Christian beliefs and practice. The “RECOVERY” acronym specifies eight recovery principles that are foundational and transformative for Christians who aim to change their problematic behaviors by experiencing the healing elements that occur with twelve-step group process in general while also learning God’s will on how the attendee should live and experience the “power to follow His will” (see “Reserve” below for details).

-

“Realize I’m not God; I admit that I am powerless to control my tendency to do the wrong thing and that my life is unmanageable” (Step 1):

Happy are those who know that they are spiritually poor (Matthew 5:3a Today’s English Version, TEV)

-

“Earnestly believe that God exists, that I matter to Him and that he has the power to help me recover” (Step 2):

Happy are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted. (Matthew 5:4 TEV)

-

“Consciously choose to commit all my life and will to Christ’s care and control” (Step 3):

Happy are the meek. (Matthew 5:5a TEV)

-

“Openly examine and confess my fault to myself, to God, and to someone I trust” (Steps 4 and 5):

Happy are the pure in heart. (Matthew 5:8a TEV)

-

“Voluntarily submit to any and all changes God wants to make in my life and humbly ask Him to remove my character defects” (Steps 6 and 7):

Happy are those whose greatest desire is to do what God Requires. (Matthew 5:6a TEV)

-

“Evaluate all my relationships. Offer forgiveness to those who have hurt me and make amends for harm I’ve done to others when possible, except when to do so would harm them or others” (Steps 8 and 9):

Happy are the merciful. (Matthew 5:7a TEV)

Happy are the peacemakers. (Matthew 5:9 TEV)

-

Reserve a daily time with God for self-examination, Bible reading, and prayer in order to know God and His will for my life and develop the power to follow His will (Steps 10 and 11).

-

Yield myself to God so that I may be used to bring this Good News to others, both by example and my works (Step 12):

Happy are those who are persecuted because they do what God requires. (Matthew 5:10 TEV)

CR meetings are run similarly to other twelve-step recovery groups, although meeting content is guided and monitored by the national CR organization. Attendees use language that generally begins with: “I am Christian who is struggling with… [problematic behavior(s)].” Mentoring and sponsorship occur at two levels, an individual level and subgroup level, with “accountability partners,” who are at least 3–4 CR members who are in recovery and share similar challenges as the attendee.

How Is CR Doing During the COVID-19 Pandemic?

During COVID-19, where face-to-face meetings are not always possible, virtual meetings have been created. Virtual meetings have changed the format, and include the following “Open share meeting format” guidelines [23]:

-

1.

Keep your sharing focused on your own thoughts, feelings, and actions (3–5 min).

-

2.

No cross talk.

-

3.

We are here to support one another. We will not attempt to “fix” one another.

-

4.

Anonymity and confidentiality are basic requirements.

-

5.

Offensive language has no place in Christ-centered recovery group, including no graphic descriptions.

-

6.

All members must use headphone.

-

7.

All members must be on camera.

-

8.

All meetings will not be recorded.

CR and Relationship to Mental Health Practitioners and the Referral Process

Unlike some twelve-step groups that do not encourage psychiatric care and psychotropic medications when needed [MA CR representative], CR as a national organization encourages mental healthcare in addition to engagement with CR and a sponsoring church. CR leaders are encouraged to facilitate and encourage treatment for attendees demonstrating a need for mental healthcare, and for attendees requesting referrals for addiction treatment. For example, an attendee who demonstrated problematic behavior during CR meetings would be approached by CR leaders, some of whom are mental health professionals, to assess “where they are at.” This CR attendee with problematic behaviors would likely be encouraged to continue with the current providers.

Case 2: Celebrate Recovery Promoting Spiritual Identity and Healing

While as noted above many individuals with a secular worldview are reluctant to engage with twelve-step groups because its spiritual approach has religious (particularly Christian) connotations, some Christian individuals may find AA not religious enough.

A 50-year-old disabled nurse has been treated for over 20 years by a Christian psychiatrist for dysthymia, recurrent major depression requiring multiple hospitalizations, and alcohol use disorder, currently in full remission. She has been taking medications including disulfiram and fluoxetine for more than 20 years, and has attended various Alcoholics Anonymous groups in the past. After leaving an abusive marriage in her 20s, she became a Christian, and stopped drinking alcohol for several years. During a recurrent depressive episode 20 years ago, she relapsed to alcohol use. She then became very involved with AA, going to daily meetings, obtaining a sponsor, and working all of the 12 steps. As a result, her recovery community and social supports grew. However, she continued to struggle with depression. As she became more involved in her Christian faith and local missionary activity, she became uncomfortable with the diversity of spirituality she encountered in her twelve-step group, and felt a need for more Christian support. Since finding Celebrate Recovery about 15 years ago, she has preferred CR to AA as a place where she honestly faces her problems, and experiences Christian hope that serves as a more complete framework for healing and recovery.

Finding the Right Mutual Help Group for Your Patient

As noted earlier in this chapter, peer-led mutual help groups that treat addictions and related problems have a long history, dating back to the 1930s with the birth of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). AA has continued to grow and now has over 2 million members worldwide. Other twelve-step groups have also prospered and grown. The twelve-step movement is likely facilitated by the culture and context in the United States, where up to 85% of the population believe in a deity or God, and where a decentralized structure of peers, individual and group autonomy, and code of anonymity foster trust and acceptance that are foundations for recovery [5].

However, as we have noted throughout this chapter, there is no one path to recovery, not all individuals believe in a deity or God, and some recovering individuals may want a more centralized organizational structure. Not surprisingly, more secular “science-based” recovery groups exist, such as SMART (Self-Management and Recovery Training) Recovery as noted earlier. Formed in the 1990s, SMART is grounded on evidence-based cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational interviewing, and rational emotive behavior therapy developed by Albert Ellis. Key differences between SMART recovery and twelve-step recovery include the former’s emphasis on changing an individual’s habits and behaviors by changing an individual’s locus of control, shifted internally to empower individuals to increase their self-reliance to curtail and eventually cease addictive behaviors. SMART Recovery posits that addiction is a habit rather than a disease and therefore requires methods that differ from those espoused by twelve-step recovery groups. SMART Recovery provides a four-point program that includes methods to achieve recovery: (1) building and maintaining motivation; (2) coping with urges; (3) managing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (through problem solving); and (4) living a balanced life [23].

Case 1 (continued): Life After Death

By faith… Samson… turned disadvantage to advantage (Hebrews 11:32–38, The Message).

By his late 30s, Eric had achieved several years of continuous sobriety through his involvement in AA. But this all changed one wintry day when Eric found himself in a hospital emergency department after injuring his back falling down an icy stairway. Eric didn’t disclose his substance use history to the emergency physician, who treated his pain with opioids and sent him home with a prescription. Eric followed up with a pain clinic, but soon found himself hopelessly dependent on the opioids. After he could no longer afford oxycodone, he turned to using heroin for the first time in his life. By his mid-forties, he had overdosed multiple times, including several near-fatal incidents. He sought out medications including buprenorphine and methadone to treat his opioid use disorder. Upon receiving take-home doses of these medications, however, he’d begin storing them up and then taking them all at once to get high.

Desperate for change, he once again checked himself into a residential treatment program. The program, offered free of charge by an urban rescue mission, featured a yearlong “biblically based” curriculum. Local community pastors would rotate through the mission, sharing their messages. Eric found himself inspired to walk the streets each afternoon sharing Christ with anyone who would listen. After completing the residential program, he enrolled in Bible college and began training to assume the pastorate of a local church where he had been ministering.

The night before Eric was to return for his final semester of Bible college, Eric’s mother received a phone call stating that her son had died of an opioid overdose which seemed likely to have been intentional. Devastated by this news, she recalled that Eric, who throughout his life had suffered from severe mood swings and had survived several serious suicide attempts (also of note, Eric had previously required antiepileptics to treat recurrent seizures in his teens, and had a family history of epilepsy and bipolar disorder) had recently been feeling especially despondent after learning that his wife had decided to separate from him and that he would not be able to see his youngest son for at least a year.

Eric’s mother struggled to understand how God could allow her son who had come so far and yet end his life so tragically. Eric’s funeral a few days later garnered a large attendance, eliciting powerful testimonies of multiple individuals whom Eric had made contact with in recent years – many of them who had long been outcasts of society, destitute, homeless, sexually exploited, or addicted to drugs – but to whom Eric had reached through his ministry of walking the streets and sharing the Good News of faith and deliverance through Christ. Despite her doubts, Eric’s mother was encouraged to see just how many persons professed that Eric had “led them to the Lord,” ushering in for them a new life of hope, recovery, and freedom.

Clinical Recommendations

The authors of this chapter suggest that rather than promoting specific twelve-step groups vs. secular groups such as SMART Recovery, it is often more prudent for clinicians to first listen to the challenges their patients have been facing and seek to understand what their patients’ goals are for treatment. After carefully listening, clinicians should describe a few of the key differences that we have outlined above and encourage them to try a variety of groups, including secular groups if the patient is so inclined. With respect to non-medication treatments, patients will ultimately decide for themselves which groups feel right for them. The goal here should be for our patients to feel accepted and in a safe space, both in their relationship with us as their treating clinicians and in the recovery group they join, so as to be encouraged and supported in their ongoing recovery.

As the final case illustrates, AA/TSF may be helpful but insufficient for patients with certain severe substance use and mental health disorders. In particular, patients with histories concerning for a non-unipolar depressive disorders (e.g., bipolar disorder, which has the highest suicide rate of any the major psychiatric diagnoses) should be referred to a licensed psychiatrist or another prescriber with expertise in treating these conditions [24]. Similarly, patients for whom there are concerns for an opioid use disorder (especially if there is a history of overdose or recent/recurrent use) should be referred to an addiction psychiatrist or other prescriber with expertise in treating substance use disorders for consideration of prescribed medications to treat opioid use disorder (MOUD: methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone) as well as dispensing of a naloxone overdose reversal kit [25], which may be lifesaving.

Conclusion and Future Directions

While one size and one type of recovery group does not fit all individuals seeking recovery, it is likely that some and possibly many different recovery groups will help our patients find a community of others who will provide hope and encouragement, thereby increasing their chances of maintaining recovery and flourishing. And for Christians seeking recovery, the best fit and path may be a group such as Celebrate Recovery, which promotes recovery and flourishing with a Christian worldview. Persons with severe substance use disorders or neuropsychiatric conditions may also require appropriate medical attention in order to achieve sustained recovery.

Future Research

As noted earlier in this chapter, there is robust evidence for the efficacy of twelve-step programs and twelve-step facilitation for alcohol dependence/alcohol use disorders. Much less is known for the efficacy and effectiveness of TS/TSF for other types of substance use disorders, although preliminary findings are promising [6]. Also, the generalizability of findings for diverse populations is largely unknown. For example, there is a paucity of research on the usefulness of twelve-step groups for adolescents and young adults, and those with various ethnicities and incomes [26]. We are not aware of research that specifically has studied recovery groups that integrate Christianity with twelve-step principles, such as Celebrate Recovery. In conclusion, interdisciplinary research done by cognitive scientists, psychologists, and scientists from other disciplines that examines the factors that mediate twelve-step recovery could improve the effectiveness of twelve-step-based therapies [27]. Interdisciplinary research in each of the above areas is needed to better understand which recovery groups are likely to help promote recovery and flourishing for the diverse individuals and populations that we treat who struggle with addictions.

Notes

- 1.

Source used throughout this section.

- 2.

Reference used throughout this section.

References

Niebuhr R. In: Platt S, editor. 1472 [Serenity Prayer]. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress; 1989.

Griswold MG, Fullman N, Hawley C, Arian N, Zimsen SRM, Tymeson HD, et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;392(10152):1015–35.

Leading Causes of Death. In: Statistics NCfH, editor. CDC; 2020.

Costs of Substance Abuse. In: Abuse NIoD, editor. NIH; 2020.

Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;(3):CD012880.

NIDA. Principles of drug addiction treatment: a research-based guide. In: NIDA, editor. NIH; 2018.

Kelly JF, Saitz R, Wakeman S. Language, substance use disorders, and policy: the need to reach consensus on an “addiction-ary”. Alcohol Treat Q. 2016;34(1):116–23.

Keener CS. Acts: an exegetical commentary: volume 1: introduction and 1: 1-247. Baker Books; 2012.

Cook CCH. Alcohol, addiction and Christian ethics. Cambridge University Press; 2006.

Markel H. An anatomy of addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the miracle drug cocaine. Vintage Books; 2012.

Adeyemo WL. Sigmund Freud: smoking habit, oral cancer and euthanasia. Niger J Med. 2004;13(2):189–95.

Jones J. How Carl Jung inspired the creation of alcoholics anonymous. 2019. Available from: http://www.openculture.com/2019/05/how-carl-jung-inspired-the-creation-of-alcoholics-anonymous.html.

Stafford T. The hidden gospel of the 12 steps. Christianity Today. 1991;35(8):14–9.

Gross M. Alcoholics Anonymous: still sober after 75 years. 1935. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2361–3.

Twelve steps and twelve traditions. New York: Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; 1981.

Simmons DL. Christianity and alcoholics anonymous: competing or compatible? WestBow Press; 2012.

Zubera A, Levounis P. Recent research into twelve-step programs. In: Herron A, Brennan TK, editors. The ASAM essentials of addiction medicine. 2nd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015. p. 399–405.

Peteet JR. A closer look at the role of a spiritual approach in addictions treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1993;10(3):263–7.

Tonigan JS, Miller WR, Schermer C. Atheists, agnostics and Alcoholics Anonymous. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(5):534–41.

Brown HP, Peterson JH. Values and recovery from alcoholism through Alcoholics Anonymous. Counsel Values. 1990;35(1):63.

Kelly JF, Stout RL, Magill M, Tonigan JS, Pagano ME. Mechanisms of behavior change in alcoholics anonymous: does Alcoholics Anonymous lead to better alcohol use outcomes by reducing depression symptoms? Addiction. 2010;105(4):626–36.

CRCR Step Study Information. 2020. Available from: https://www.celebraterecovery.com/crcr.

About SMART Recovery. 2020. Available from: https://www.smartrecovery.org/about-us/.

Administration SAaMHS. SAMHSA advisory: an introduction to bipolar disorder and co-occurring substance use disorders. In: SAMHSA, editor. 2016.

Schuckit MA. Treatment of opioid-use disorders. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):357–68.

Nash AJ. The twelve steps and adolescent recovery: a concise review. Subst Abuse. 2020;14:1178221820904397.

Segal G. Alcoholics Anonymous “Spirituality” and long-term sobriety maintenance as a topic for interdisciplinary study. Behav Brain Res. 2020;389:112645.

Arciniega LT, Arroyo J, Barrett D, Brief D, Carty K, Gulliver SB, et al. In: Miller WR, editor. Combined behavioral intervention (CBI): therapist manual. Project COMBINE; 2002. p. 217.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

How to Do TSF?

Due to space limitations, we refer interested clinicians seeking practical guidance on how to do TSF to the Project COMBINE Cognitive Behavioral Therapy manual [28]. Briefly, the steps include:

-

Provide a rationale for mutual-support group involvement.

-

Ask your patient for the reasons why additional support could be helpful.

-

Explore said patients’ attitudes and beliefs about mutual support.

-

Give information about available groups.

-

Give practical information on what to expect in a recovery group.

-

Encourage sampling more than one group; provide referral information.

-

Make a specific action plan.

For more detailed information, please refer to the above-referenced CBT manual.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hathaway, D.B., Dawes, M. (2021). Addiction and Twelve-Step Spirituality. In: Peteet, J.R., Moffic, H.S., Hankir, A., Koenig, H.G. (eds) Christianity and Psychiatry. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80854-9_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80854-9_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-80853-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-80854-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)