Abstract

Identifying the end-of-life stage in dementia is often difficult. A recently developed model using indicators of survival probability can aid in estimating life expectancy. Person-centred care, an essential aspect of end-of-life care for people with dementia, takes their medical, psychological, social and spiritual concerns into account. Although the disease trajectory varies depending on comorbidities and type of dementia, dementia follows a pattern of functional decline, leading to considerable frailty and deterioration in the last months of life. Good comfort care, as the most appropriate care goal in this disease stage, covers: person-centred care, optimal treatment of symptoms and providing comfort, psychosocial and spiritual support, family care and involvement, communication and shared decision making, setting care goals, advance care planning and continuity of care. Physical symptoms, most frequently pain and shortness of breath, also need to be addressed. Psychological discomfort may be overlooked or medicalised, or may result in agitation, which often occurs at the end of life and may be related to other causes, e.g. physical discomfort or illness. A stepwise approach combining medical and psychological interventions appears to be most useful for these symptoms. In the social domain, the cornerstones of good person-centred care are family support, educating the family, family involvement in caregiving and bereavement support. Basic spiritual support should include determining religious affiliation and involvement, particularly in terms of familiar religious rituals, artefacts and symbols, as well as the narrative of the patients’ life, spiritual reminiscing serving as a way to explore this, also in severe dementia. Advance care planning and a three-step systematic approach to shared decision making may help in providing person-centred care that maximises comfort for the patient and families at the end of life. Similar to other phases of the disease, measurement instruments are useful and may help patients to non-verbally express their level of comfort. Good instruments are available for quality of care, dying, measuring pain and spirituality, but also physician communication with family caregivers and staff knowledge on palliative care.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Determining when an individual with dementia has entered the end-of-life stage is often difficult as a gradual decline in health and frailty are generally part of the disease trajectory. It is not uncommon for the advanced stage of dementia to last several years. A recently developed model using indicators of survival probability: higher age, male, increased comorbidity burden, lower cognitive function at diagnosis and non-Alzheimer dementia (e.g. frontotemporal dementia or Lewy body dementia) can provide physicians and others with an estimation of life expectancy [1].

Good quality care for patients with dementia is chiefly defined as person-centred care designed to relieve biomedical and physical symptoms, but that also takes psychological, social and spiritual issues in to consideration:

Person-centred care should not only be directed at compensating for what people with dementia cannot do, but also at facilitating their interests, pleasure and use of their capacities. Thus, as research progresses beyond caregiving to embrace the wider concepts outlined by Kitwood, person-centred care may become a facilitator for people with dementia to live life as fully as possible, whether they are supported in the own home or in a care home. [2]

The relative importance of these aspects of care will vary across time as well as between patients, changing in keeping with the individual’s experience of dementia. Although physical concerns and treatments may be given more attention at the time of diagnosis and in the terminal phase, it is important to focus on them in all phases of the disease, keeping in mind that expressing discomfort in stages that are not end of life can be equally challenging. The inclination is to view challenging behaviour as a medical problem to address with medication. Behavioural and psychosocial symptoms of dementia (BPSD) , including challenging behaviour, however, require a person-centred diagnostic approach that incorporates the biomedical domain. Conclusions on the underlying causes should only be made based if the evidence supports them or if arguments can be made that the behaviour is caused by a specific underlying cause. This type of approach may limit the risk of medicalisation and of overlooking serious but treatable medical causes [3]. The social aspects of dementia care primarily concern the people with dementia themselves and involve their capacity to meet their potential and fulfil their obligations; their ability to manage life with some degree of independence; and participation in social activities [4]. Social aspects also comprise supporting family caregivers, keeping them informed, ensuring their participation in advance care planning (ACP) and offering support as they gradually lose their loved, an aspect that remains important throughout the disease trajectory. Studies show that a good match between care providers and families in need of support leads to better quality of care [5]. At the time of diagnosis spiritual concerns may arise as an existential crisis, while at the end of life the need for reconciliation and being at peace with the life they lived may develop, making spiritual and religious support increasingly important as death becomes imminent [3].

Where people die when they have dementia differs greatly between countries. A study of five European countries showed that a majority of people with dementia died in long-term care facilities, ranging from 50.2% in Wales to 92.3% in the Netherlands, 89.4% of whom died in a specialised nursing home and 10.6% in a general care home for older adults. More people with dementia died in hospital in the United Kingdom (England 36.0%; Wales 46.3%; Scotland 33.9%) and Belgium (22.7%) than in the Netherlands (2.8%). In Belgium 11.4% died at home, while 5% or less did so in the other countries. Less than 1% died in a hospice [6]. A 2014 study performed in 14 European and non-European countries reported that death in long-term care facilities was highest in the Netherlands (93.1%) and lowest in Korea (5.5%). There were no deaths in long-term care reported in Hungary and Mexico. Death in hospital was highest in Korea (73.0%) and lowest in the Netherlands (3.8%). Dying at home with dementia was highest in Mexico (69.3%), and lowest in Canada (3.4%), while death with dementia in a hospice setting was highest in the USA (2.9%) [7]. The disease trajectory varies depending on comorbidities, type of dementia and other factors [8]. Often, dementia follows a pattern of decline, leading to frailty and severe disabilities in the last years of life, with a substantial deterioration in function (e.g. increased ADL dependency) in the last months of life. Concurrent illnesses may accelerate the decline but generally patients suffer a steady “prolonged dwindling” [9]. Some patients, however, will not live to advanced stages and may die with mild dementia.

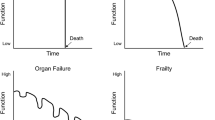

As the disease progresses, the prioritisation of care goals may change. Three care goals stand out when health declines, also in dementia: prolonging life, maintaining function and maximising comfort [10]. At the end of life, when the first two goals are no longer relevant, comfort care is the best option. Figure 17.1, which depicts how care goals and priorities change during the various stages of dementia, illustrates how some care goals may apply simultaneously but are of varying relevance depending on the stage of dementia. For example, with moderate dementia the three goals may apply simultaneously, though maintenance of function and maximisation of comfort can be prioritised over prolongation of life. In end-of-life care, maximisation of comfort is the most appropriate care goal. Comfort care does not aim to hasten death or to prolong life, which means it does not preclude treating health issue such as infections with antibiotics, as this may be the best way to resolve burdensome symptoms. This type of goal-oriented approach may simplify ACP discussions and the process of shared decision making for professionals, family caregivers and patients [9].

Dementia progression and suggested prioritisation of care goals (Source: van der Steen et al. [9]). An evaluation of palliative care contents in national dementia strategies in reference to the European Association for Palliative Care white paper; First published online 13 February 2015. Miharu Nakanishi, Taeko Nakashima, Yumi Shindo, Yuki Miyamoto, Dianne Gove, Lukas Radbruch, and Jenny T. van der Steen. International Psychogeriatrics (2015), 27:9, 1551–1561 C [1] International Psychogeriatric Association 2015. doi:10.1017/S1041610215000150

Domains of Good End-of-Life Care in Dementia

Concordant with major studies and publications, the following domains of end of-life care in dementia are currently being promoted: (1) optimal treatment of physical symptoms, providing comfort, avoiding burdensome or futile treatment, (2) optimal treatment of challenging behaviour BPSD, (3) social support, family support and involvement in care, (4) spiritual support and (5) ACP and shared decision making [3, 9].

-

1.

Optimal treatment of physical symptoms, providing comfort and avoiding burdensome or futile treatment

Pain and shortness of breath frequently occur in patients with dementia at the end of life [8], with a prevalence that is about as frequent as in other diseases, such as cancer, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease and renal disease [11]. For instance, two studies show that pain occurs 12–76% of the time in people with dementia, and in 35–96% in cancer patients. Shortness of breath is reported in dementia in 8–80% of the time, in cancer 12–79%. A study on symptom prevalence and prescribed treatment in nursing home residents with dementia, and their association with quality of life in the last week of life, showed that pain was the most common symptom (52%), followed by agitation (35%) and shortness of breath (35%). Pain and shortness of breath were mostly treated with opioids and agitation mainly with anxiolytics. On the day of death, 77% received opioids and 21% received palliative sedation. Pain and agitation were associated with lower quality of life [1]. Since shortness of breath may be an alarming symptom, it may attract more attention from caregivers and be treated early, contributing to better quality of dying [12]. Death from respiratory infection was associated with the largest symptom burden, and studies have reported undertreatment of symptoms, specifically treatment of pain and shortness of breath with opioids, possibly due to concerns about undesirable side effects, such as delirium [1, 9].

Symptomatic treatment trends, such as symptom relief in patients with dementia with pneumonia, for example, with antipyretics are becoming more common, providing more comfort for the patient [9]. Other reported conditions are aspiration and pressure ulcers, especially in nursing home residents. Although undertreatment of symptoms is reported to be a concern, overtreatment with burdensome interventions is also a concern, and a supportive or palliative approach may be more applicable than hospital admission in older people with dementia [13]. Tube feeding and antibiotics are an example of areas where under- or overtreatment occur. Using antibiotics in severe dementia at end of life is a complex choice, as they may prolong life but often only for days, which is why complex treatment decisions should take into account that death may be delayed death but the dying process prolonged [14]. A prognostic model that includes gender, respiratory rate, respiratory difficulty, pulse rate, decreased alertness, fluid intake, eating dependency and pressure sores as variables has been developed and tested to support physicians in predicting the mortality risk in nursing home residents. The model allows physicians to substantiate the initiation of palliative care when applicable [15]. In several countries, patients with dementia are sent to the emergency department or hospitalised shortly before death, and sometimes even admitted to an intensive care unit [16]. In this prospective study, within 1.5 years, more than half of the residents had infectious episodes, and 86% had eating problems. Survival was poor after the onset of these complications. Families and caregivers must be told that the underlying cause of death will be a major illness, in this case dementia, and that using potentially burdensome interventions of unclear benefit, such as tube feeding and hospitalisation, in nursing home residents with advanced dementia nearing the end of life is not recommended. In Israel, a quarter of all resources in medical wards are used on patients with dementia in the last stage of disease, and shared decision making and ACP may prevent burdensome interventions and hospitalisations [17]. Shared decision making and ACP may also prevent the use of medication that is no longer useful, which is unfortunately still a widespread practice in many countries [18].

-

2.

Optimal treatment of challenging behaviour and BPSD

Agitation, which also frequently occurs in patients with dementia at the end of life, is less often assessed in studies on the last phase of life but may be as common as pain and shortness of breath [8]. Agitation may be related to other problems, such as cognitive impairment, depression or pain. A study showed that comprehensive training in behavioural management, where pain medication is the first consideration, resulted in less observed pain [19], improved behaviour and reduced use of psychotropic medication [20]. Other BPSD, including behaviour that may be problematic for the patient, such as apathy, are another important aspect of dementia [9]. A multidisciplinary palliative approach may be helpful in anticipating, assessing and managing problems. With challenging behaviour, integrating specific expertise from geriatrics and dementia care specialists is recommended, just as (clinical) psychology can play a significant role. Evidence shows that a stepwise approach with a combination of medical and psychosocial interventions is most useful [19, 21].

-

3.

Social support, family support and involvement in care

An example of family support is providing social support when relatives suffer from caregiver burden and perhaps struggle to combine caring with their other obligations. They may also need support with the institutionalisation of the patient, when a major decline in health occurs and death is near. Families may need education regarding the progressive course of the dementia and (palliative care) treatment options. This should be a continuous process addressing specific needs in different stages that is based on an assessment of how receptive the family is to learn more. Families need support in their new role as (future) proxy decision maker. They may also need education and support in dealing with patient’s challenging behaviours [9].

Family involvement should be encouraged as many families wish to be involved in care, even when the patient is admitted to a long-term care home. Professional caregivers should have an understanding of family needs related to suffering from chronic or prolonged grief through the various stages, and with evident decline. In addition, bereavement support should be offered. Following the death of the patient, family members should be allowed adequate time to adjust after often a prolonged period of caring for the patient. Taking care of the body of their deceased loved one may be a first step in this process [9]. Some interesting and promising interventions have been developed, such as Reclaiming Yourself, a structured writing tool for bereaved spouses of people with dementia that captures the overall bereavement experience, describing the need for both continuity and growth as the spouses renegotiate life and their identity after the end of caregiving and the death of their loved one. The tool guides and encourages reflection on these themes: experiences as a caregiver, navigating regrets, changes in oneself, personal strength and support networks [22].

-

4.

Spiritual support

A consensus definition of spirituality is: “the dynamic dimension of human life that relates to the way persons (individual and community) experience, express and/or seek meaning, purpose and transcendence, and the way they connect to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, to the significant and/or the sacred” [23]. Although this appears to be a rather abstract concept in the context of patients with severe dementia at the end of their lives, it may still be particularly important for their well-being.

A variety of interventions can support patients with dementia in terms of their spiritual well-being. For example, spiritual caregiving in dementia should as a minimum include an assessment of religious affiliation and involvement, sources of support and spiritual well-being. Patients and their families can provide this information upon admittance to a nursing home, e.g. in the form of a biography (life story) that includes meaningful events and encounters, positive and negative, and sources of support (e.g. people, but also religious or spiritual support). A concrete example is life story work, which is intended to underpin person-centred care in dementia [24]. If the patient is in spiritual distress , referral to experienced spiritual counsellors, psychologists or social workers working in nursing homes may be appropriate when available [9, 25]. Conversations and possibly rituals with such professionals may be beneficial not only to the patient and their loved ones but provide essential information that may also be supportive to families and professionals.

Paying attention to familiar religious rituals, artefacts and symbols may give people a deep sense of connection with the significance of their religion. Singing hymns or religious songs, praying, reading the Bible, Koran, Tora or other religious books, holding a rosary or other holy artefact, looking at a statue of Buddha or the Virgin Mary, may provide a meaningful connection not based on overt cognition [9].

Our connectedness to and knowing of ourselves is expressed and constituted through the narrative of our lives. Our selves are held within a web of narratives, which is why it is important to facilitate people with dementia in sharing their life narratives, to co-construct their life stories with their loved ones [26]. By inviting nursing home residents with dementia to tell their life stories, or even early memories, they are invited to make sense of themselves and of their place in the world. This may support their self-worth, reduce anxiety, improve their mood and boost the way they feel. Through spiritual reminiscence, the personal narrative and the importance of spirituality may be explored, even in severe dementia. Mackinlay and Trevitt developed a practical guide that teaches caregivers how to facilitate engaging and stimulating spiritual reminiscence sessions with older people, particularly people with dementia. The guide provides a set of questions and discussion topics for a 6-week group programme that contains step-by-step strategies to prompt discussions on grief, guilt, fears, regrets, joys and issues concerning death and dying, giving meaning, hope and perspective to the experiences and feelings of people living with dementia [27].

-

5.

ACP and shared decision making

ACP and shared decision making may help in providing person-centred care that maximises comfort for patient and families at the end of life [28]. ACP may be defined as: “a continuous, dynamic process of reflection and dialogue between an individual, those close to them and their healthcare professionals, concerning the individual’s preferences and values concerning future treatment and care, including end-of-life care” [29]. Despite recognition of the importance of ACP, it still happens infrequently. Within the ACP process, a three-step systematic approach to shared decision making may be helpful in supporting decisions on treatment choices. In step one, all relevant information can be shared with patients and their families; second, treatment options can be described to aid them in the process of deliberating treatment choices; and in the last step, patients and their families can be given help to explore their preferences and make decisions [30]. The literature identifies these key triggers for ACP conversations: admission to a nursing home, initiation of palliative care, deterioration of the condition or upon request. Specifically, for dementia, key moments might be the period around diagnosis, while discussing the overall general care plan and/or when changes occur in health status, place of residence or financial situation [29]. As dementia progresses, cognitive activity and abstract thinking may become more and more difficult. This does not preclude ACP but does make discussing it more difficult, especially at the end of life. Consequently, it is important to adjust the communication style and content to suit the individual’s current level, just as it is best to hold ACP conversations on several occasions over a period of time. In addition, healthcare professionals should include significant people in the patient’s life in ACP and people with the ability to be involved in ACP conversations and to become surrogate decision makers [29]. In nursing homes, ACP was found to positively influence the quality of care and provide greater harmony between residents at the end of lives, their loved ones and continuity of care. Similar interventions in the outside community improved the quality of life for patients but did not influence the level of compliance between patient wishes and the care provided [31].

The Use of Measurement Instruments in End-of-Life Dementia Care

People with end-stage dementia often have difficulty expressing their level of comfort verbally, and since comfort care is the primary care goal, validated measurement instruments can aid in monitoring and providing optimal care. The End-of-Life in Dementia-Satisfaction with Care and the Family Perceptions of Care Scale, which are the most valid and reliable for measuring quality of care, are administered by family members in the last month of life and validated in nursing home/long-term care populations. The End-of-Life in Dementia-Comfort Assessment in Dying and Mini-Suffering State Examination are valuable for measuring quality of dying [32, 33].

Developed internationally, validated in a population of people with dementia and administered by nurses, the Pain Assessment in Cognitive Impairment scale [34, 35] specifically assesses pain in dementia, and its use in practice is promising [36]. A short training in using the instrument’s facial descriptor items is required.

As physician communication with family caregivers is essential at the end of life, the Family Perception of Physician-Family caregiver Communication instrument can be of importance in assessing family perceptions of communication between physicians and family caregivers [37]. To evaluate the knowledge of the staff on palliative care, the Palliative Care Survey is also a useful tool [38]. Finally, the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—spiritual well-being scale, which is self-administered by patients and validated in nursing home residents with and without dementia, is valuable for assessing spiritual aspects in patients with dementia [39].

In summary, an increasing amount of scientific evidence supports the use of measuring instruments in end-of-life care in dementia (Table 17.1).

Conclusion

In end-of-life care for patients with advanced dementia, person-centred care is preferred that focuses on biomedical, psychological, social and spiritual concerns. Comfort care is the most appropriate care goal. Important domains in good end-of-life care in dementia are: physical symptoms (most frequently pain and shortness of breath). Psychological concerns may be overlooked or medicalised. Agitation, a neuro-psychiatric symptom that often occurs at the end of life in dementia, may be related to other issues. A stepwise approach that contains a combination of medical and psychological interventions appears to be the most useful for these symptoms. In the social domain, family support, family education, family involvement in caregiving and bereavement support are cornerstones of good patient-centred care. Spiritual support should at least involve an assessment of religious affiliation and involvement, but also focus on familiar religious rituals, artefacts and symbols, in addition to the life narrative of the patient, using spiritual reminiscence to explore this, also in severe dementia. ACP and the three-step systematic approach of shared decision making may be supportive in providing person-centred care that makes the patient at the end of life and their families as comfortable as possible. The use of measurement instruments is helpful in end-of-life care for patients with dementia who often have difficulty verbally expressing their level of comfort for in the end stage of the disease. Validated and reliable instruments are available to assess quality of care and dying, pain and spirituality, physician communication with family caregivers and staff knowledge on palliative care to help achieve the aim of good comfort care that is person-centred.

Abbreviations

- ACP:

-

Advance care planning

- BPSD:

-

Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia

- EOLD-CAD:

-

End-of-Life in Dementia-Comfort Assessment in Dying

- EOLD-SWC:

-

End-of-Life in Dementia-Satisfaction with Care

- FPCS:

-

Family Perceptions of Care Scale

- FPPFC:

-

Family Perception of Physician-Family caregiver Communication

- MSSE:

-

Mini-Suffering State Examination

- PAIC15:

-

Pain Assessment in Cognitive Impairment

References

Haaksma ML, Eriksdotter M, Rizzuto D, Leoutsakos J-MS, Olde Rikkert MGM, Melis RJF, Garcia-Ptacek S. Survival time tool to guide care planning in people with dementia. Neurology. 2020;94:e538–48. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000008745.

Vernooij-Dassen M, Moniz-Cook E. Person-centred dementia care: moving beyond caregiving. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(7):667–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1154017.

Houttekier D, Cohen J, Bilsen J, Addington-Hall J, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Deliens J. Place of death of older persons with dementia. A study in five European countries. JAGS. 2010;58(4):751–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02771.x.

Dröes RM, Chattat R, Diaz A, Gove D, Graff M, Murphy K, Verbeek H, Vernooij-Dassen M, Clare L, Johannessen A, Roes M, Verhey F, Charras K. Social health and dementia: a European consensus on the operationalization of the concept and directions for research and practice. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(1):4–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1254596.

Dam AEH, Boots LMM, Boxtel MPJ, Verhey FRJ, de Vugt ME. A mismatch between supply and demand of social support in dementia care: a qualitative study on the perspectives of spousal caregivers and their social network members. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(6):881–92. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217000898.

Hendriks SA, Smalbrugge M, Hertogh CM, van der Steen JT. Dying with dementia: symptoms, treatment, and quality of life in the last week of life. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;47(4):710–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.015.

Reyniers T, Deliens L, Pasman LH, Morin L, Addington-Hall J, Frova L, Cardenas-Turanzas M, Onwuteaka-Philipsen B, Naylor W, Ruiz-Ramos M, Wilson DM, Loucka M, Csikos A, Joo Rhee Y, Teno J, Cohen J, Houttekier D. International variation in place of death of older people who died from dementia in 14 European and non-European countries. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(2):165–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.11.003.

van der Steen JT. Dying with dementia: what we know after more than a decade of research. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(1):37–55. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-2010-100744.

van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, de Boer ME, Hughes JC, Larkin P, Francke AL, Jünger S, Gove D, Firth P, Koopmans RT, Volicer L. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC). Palliat Med. 2014;28(3):197–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313493685. Epub 2013 Jul 4.PMID: 23828874.

Gillick MR. Adapting advance medical planning for the nursing home. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(2):357–61. https://doi.org/10.1089/109662104773709521.

Solano JP, Gomes B, Higginson IJ. A comparison of symptom prevalence in far advanced cancer, AIDS, heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal disease. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2006;31(1):58–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.06.007.

Caprio AJ, Hanson LC, Munn JC, et al. Pain, dyspnea, and the quality of dying in long-term care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:683e688.

Sampson EL, Leurent B, Blanchard MR, Jones L, King M. Survival of people with dementia after unplanned acute hospital admission: a prospective cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(10):1015–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3919.

van der Steen JT, Lane P, Kowall NW, Knol DL, Volicer L. Antibiotics and mortality in patients with lower respiratory infection and advanced dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(2):156–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2010.07.001.

Rauh SP, Heymans MW, van der Maaden T, Mehr DR, Kruse RL, de Vet HCW, van der Steen JT. Predicting mortality in nursing home residents with dementia and pneumonia treated with antibiotics: validation of a prediction model in a more recent population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2019;74(12):1922–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/gly260.

Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1529–38. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0902234.

Salz IW, Carmeli Y, Levin A, Fallach N, Braun T, Amit S. Elderly bedridden patients with dementia use over one quarter of resources in internal medicine wards in an Israeli hospital. Isr J Health Policy Res. 2020;9(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13584-020-00379-0.

Rausch C, Hoffmann F. Prescribing medications of questionable benefit prior to death: a retrospective study on older nursing home residents with and without dementia in Germany. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(6):877–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-020-02859-3.

Pieper MJC, van der Steen JT, Francke AL, Scherder EJA, Twisk JWR, Achterberg WP. Effects on pain of a stepwise multidisciplinary intervention (STA OP!) that targets pain and behavior in advanced dementia: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Palliat Med. 2018;32(3):682–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216316689237.

Pieper MJC, Francke AL, van der Steen JT, Scherder EJA, Twisk JWR, Kovach CR, Achterberg WP. Effects of a stepwise multidisciplinary intervention for challenging behavior in advanced dementia: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(2):261–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13868.

Zwijsen SA, Gerritsen DL, Eefsting JA, Smalbrugge M, Hertogh CMPM, Pot AM. Coming to grips with challenging behaviour: a cluster randomised controlled trial on the effects of a new care programme for challenging behaviour on burnout, job satisfaction and job demands of care staff on dementia special care units. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.10.003.

Peacock S, Bayly M, Gibson K, Holtslander L, Thompson G, O’Connell M. Development of a bereavement intervention for spousal carers of persons with dementia: the Reclaiming Yourself tool. Dementia (London). 2020;20(2):653–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220909604.

Nolan S, Saltmarsh P, Leget C. Spiritual care in palliative care: working towards an EAPC Task Force. Eur J Palliat Care. 2011;18(2):86–9.

McKinney A. The value of life story work for staff, people with dementia and family members. Nurs Older People. 2017;29(5):25–9. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop.2017.e899.

Gijsberts MJHE, van der Steen JT, Hertogh CMPM, Deliens L. Spiritual care provided by nursing home physicians: a nationwide survey. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001756.

Baldwin C. Narrative, supportive care, and dementia: a preliminary exploration. In: Hughes JC, Lloyd-Williams M, Sachs GA, editors. Supportive care for the person with dementia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. isbn:978019955413.

Mackinlay E, Trevitt C. Finding meaning in the experience of dementia: the place of spiritual reminiscence work. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2012. isbn:9781849052481

Dening KH, Sampson EL, De Vries K. Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. Palliat Care Soc Pract. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1177/1178224219826579.

Piers R, Albers G, Gilissen J, De Lepeleire J, Steyaert J, Van Mechelen W, Steeman E, Dillen L, Vanden Berghe P, Van den Block L. Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0332-2.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams D, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, Cording E, Tomson D, Dodd C, Rollnick S, Edwards A, Barry M. Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1361–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6.

Kelly AJ, Luckett T, Clayton JM, Gabb L, Kochovska S, Agar M. Advance care planning in different settings for people with dementia: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. Palliat Support Care. 2019;17(6):707–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951519000257.

Pivodic L, Smets T, Van den Noortgate N, et al. Quality of dying and quality of end-of-life care of nursing home residents in six countries: an epidemiological study. Palliat Med. 2018;32(10):1584–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216318800610.

van Soest-Poortvliet MC, van der Steen JT, Zimmerman S, et al. Psychometric properties of instruments to measure the quality of end-of-life care and dying for long-term care residents with dementia. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(4):671–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9978-4.

Corbett A, Achterberg W, Husebo B, Lobbezoo F, de Vet H, Kunz M, Strand I, Constantinou M, Tudose C, Kappesser J, de Waal M, Lautenbacher S. An international road map to improve pain assessment in people with impaired cognition: the development of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC) meta-tool. BMC Neurol. 2014;14(1):229. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-014-0229-5.

Kunz M, de Waal MWM, Achterberg WP, Gimenez-Llort L, Lobbezoo F, Sampson EL, van Dalen-Kok AH, Defrin R, Invitto S, Konstantinovic L, Oosterman J, Petrini L, van der Steen JT, Strand L-I, de Tommaso M, Zwakhalen S, Husebo BS, Lautenbacher S. The Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition scale (PAIC15): a multidisciplinary and international approach to develop and test a meta-tool for pain assessment in impaired cognition, especially dementia. Eur J Pain. 2020;24(1):192–208. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1477.

Lautenbacher S, Walz AL, Kunz M. Using observational facial descriptors to infer pain in persons with and without dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0773-8.

Biola H, Sloane PD, Williams CS, Daaleman TP, Williams SW, Zimmerman S. Physician communication with family caregivers of long-term care residents at the end of life. JAGS. 2007;55(6):846–56. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01179.x.

Van den Block L, Honinx E, Pivodic L, et al. Evaluation of a palliative care program for nursing homes in 7 countries: the PACE cluster-randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;180(2):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5349.

Santana-Berlanga NDR, Porcel-Gálvez AM, Botello-Hermosa A, Barrientos-Trigo S. Instruments to measure quality of life in institutionalised older adults: systematic review. Geriatr Nurs. 2020;S0197-4572(20):30054–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.01.018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gijsberts, MJ.H.E., Achterberg, W. (2021). End-of-Life Care in Patients with Advanced Dementia. In: Frederiksen, K.S., Waldemar, G. (eds) Management of Patients with Dementia. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77904-7_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77904-7_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-77903-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-77904-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)