Abstract

Issues relating to ethics and how moral principles evolve are imminently engrained in culture. Culture and technology cannot be separated from one another, as both are processes and reflections of social cognition and experience through action and practice. Technology is the embodiment of values and enabler of culture. As technology develops and human relationships to information technology (IT) become ever more intricate and intimate the cultural framework underpinning values and ethics also morphs. The Internet is everywhere and humans are reliant on it for everything from banking to maintaining family relationships. Anything an individual could possibly desire can be found within the masses of information and websites. The Internet has made access to domains that were either rare luxury or forbidden seemingly easy, convenient and free. What was once considered taboo and hedonic indulgence is now not only openly available, but widely accepted within popular Western culture. This paper concentrates on the topic of technosexuality, Internet facilitated sexual encounters, technologically enabled sex, and ideas around ethics and changing moral values. We refer to ‘ethical stance’ as a reflection of the socio-psychological positioning of humans in relation to their moral views and understandings. This is a theoretical paper that draws on contemporary examples from dating Apps and embodied technology (sex robots) in light of current discourse expressed in public online media.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The relationship between humans, sex and technology can be seen throughout human history. Whether it be to enhance sexual appeal, enhance sex, or compensate for sexual partners – either in a relationship or not – technology has been constantly present through the acts and creation of human beings. One historical example can be seen in the poet Publius Ovidius (Ovid) Naso’s (43 BC- 17/18 AD) work Metamorphoses [1]. In the epic Metamorphoses, Ovid describes the story of Pygmalion, a single man and sensitive soul who was disheartened by witnessing the poor conditions of women. He chose to remain single for many years, during which time he carved a statue of a woman out of ivory. Pygmalion fell in love with the beauty of his ivory creation. He dressed the statue, whispered to it, kissed it and even felt that the statue had returned his kisses. Eventually after praying that she be his wife, the statue of perfection was transformed into flesh and blood.

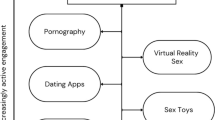

The story characterizes two important points: 1) the fact that sex technology and objects used as human substitutes has a long history; and 2) that sex technology is not necessarily about human flesh and satisfaction through interaction with objects, but in fact human-to-human interactions and relations. The tale of Pygmalion indeed shows disillusionment between the reality of others (women, their behavior, being and conditions) and our expectations of what they should be - our ideals of others. This is known often times as the Pygmalion (or Rothendal) effect [2]. Yet, the Pygmalion effect concentrates on explaining the correlation between expectations of high performance and actual realization of high performance [3]. This matter cuts at the heart of traditional debate in sex technology, ethics and fields such as gender studies in the conflict between organic versus artificial, unconditional romantic (love) versus constituent, or confluent [4]. The following paper delves into ethical matters concerning technosexuality in light of self and culture (see Fig. 1). Technosexuality refers to engagement with sex-oriented technology and technology that facilitates sexual encounters. The focus in particular is on changing cultural conditions and ethical stance, and observing the varying types of ethical issues that are still arising given the evolving techno-cultural landscape.

2 Ethics, Moral Values and Ethical Stance

In this section, we describe what ethics are from the perspective of this paper, and explain our position on ethical stance. In the first place, ‘ethics’ is an area of philosophy that aims at examining and explaining the ways in which people evaluate phenomena in terms of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, or ‘good’ and ‘evil’ [5]. Ethics, are philosophical collections of moral principles that exist on differing levels in relation to each individual and their positioning in society [6], can be seen as culturally, socially and individually constructed [7]. They are used as a means by which people assess phenomena such as other people and their character traits, the way they behave and their associations (institutions, groups or ideologies they represent) [8], as well as things or systems, for instance technological systems such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), robotics and social media. Ethics is the term that explains sets of conditions that are thought to be designed to maximize benefits for as many people and parties possible [9]. Yet, they also are psychologically and socially present through immaterial values and frameworks through which we judge as to whether someone has behaved in an appropriate or ‘good’ way, or whether or not they have acted inappropriately with the wrong intentions in mind - the intention to act for personal benefit at the expense of others.

Moral principles, or ethics, guide the ways in which we understand what is morally right and morally wrong [8]. The subjects of these evaluations are not simply other people or e.g., technology, but also societal frameworks as a whole. For instance, do we always agree with the legislation and policies of our own countries? What about in regards to regimes and dictatorships? Just because we are told to act in a certain way, do we actually agree with these orders or the motives behind them? In other words, ethics is a complex philosophical and sociological field, in which the dynamics between individual, collective and society are analyzed from multiple perspectives and on varying levels, particularly when considering the types of ethics related subjects in question and why they exist [7].

2.1 Areas of Ethics

The field of ethics is said to be divided into three distinct areas: a) metaethics - this deals with what judgments mean, what they concern, whether or not there are multiple viewpoints to consider regarding particular subjects (i.e., is there really a true or false in relation to the matter in question, and if so, what is it?); b) normative ethics - looks at what these judgments comprise (the content and constructs of the judgments) - i.e., what parts of an action make it right or wrong, and in what ways can a good life be defined? [11]; and c) applied ethics - how ethics are played out in practice is relation to diverse issues such as animals rights, abortion, homosexuality, infanticide, war etc. [11] Moral principles or guidelines are translated to apply to the evaluation of contemporary life and society, this is achieved through focusing on isolating the properties of a just and fair society [10]. Lately, we can see this act of normative ethics being permeated through societal levels, particularly in discourse relating to design, technology and business. Sustainability in particular, is primarily concerned with operationalizing ethics - ascertaining what are the appropriate and correct ways of undertaking operations and considering design - in order to create and maintain structures, ecosystems and relations that will sustain in the long-term [11]. This also entails understandings of accountability and responsibility within action and interaction relationships [12].

Thus, within ethics, there are not only differing approaches but also differing scopes of promoting these understandings that entail i.e., moral theory or applied ethics. Moral theory aims to generate a systematic viewpoint on a wide range of disagreements and moral convictions and why these exist [13]. Applied ethics on the other hand, is seen in the above example of current trends in sustainability (environmental, social, economic etc.) and corporate responsibility in which ethical guidelines or moral principles are converted into action. Accountability could be said to be one of the grey areas in this ethical chain [12], and this is something that will be discussed more in relation to evolving ethical stance.

2.2 Ethical Stance and Moral Positioning

Ethical stance, or as some deem moral positioning, can be seen as the perspective from which an individual believes an action, matter or belief is correct and true [14, 15]. As John Seeley has aptly described, “An ethic is a morality become in its custom; it is self-willed, and the strength that makes possible that strenuous enactment lies in self-location, the appropriate placing of the self” (p. 382). This placing of the self, or positioning of oneself is either the active or passive choice to assume a stance. In other words, ethics exist and operate in relation to normified action (custom) and agency. People consciously on various levels decide what is right and wrong - locating themselves in relation to these criteria. As children humans are born within specific frameworks or social-cultural structures that define good and evil, yet as one grows older and social mechanisms become more explicit, people become more capable of locating themselves in relation to specific phenomena. This is what is meant here by ethical or moral stance. Seeley [16] goes on to outline the fact that ethical stance is taking a position in light of a dis-position - a position and posture that is acquired, indicated and held. Ethical stance is about making both explicit and implicit programmatic declarations. Intentionality, or intentions, can be viewed as sub-stances in relation to stance. Thus a stance, or when someone is taking a ‘stand’ (against or for) people are implying a status - the act (motus or movement) towards/against something.

Moral positioning can be seen as slightly different to ethical stance. In the case of moral positioning, the act of moralizing itself can be understood as a social phenomenon [13]. The theory of moral positioning aims to examine and discover patterns that aid in explicating social interaction during conflict. In turn, these patterns can be seen to be used by ordinary people on a daily basis during interaction with one another. Moral positioning is used to describe the process in which people attribute moral meaning and identity to objects and subjects. Where ethical stance can be seen in great respect as an introspective process of positioning the self, moral positioning can be seen as an interactive process in which people dialogically place themselves in a position according to a moral issue. This dialogical placement happens in social interaction. Unlike the deeper roots of ethical stance, moral positioning does not assume the handling of morality according to religion or philosophy, and is not concerned with framing phenomena as either good or evil. Rather, it is about how people apply morality in their everyday lives. Aström [17] focused on moral patterns either implicit or explicit, as well as moralizing processes. Sub-processes involved in this can be considered as moral gate-keeping, competitive moral positioning and moral position fixation.

We may consider ethical stance in particular, as not so much fixed, but gradually evolving over time. As people learn, experience and are exposed to different situations and viewpoints, their ethical stance evolves [18]. Where philosopher David Hume had argued that moral reason, or the way in which we ethically frame issues, is highly contingent on emotional reactions (this also links to further scholarship on evolutionary ethics for instance) [19]. Upon greater inspection this relationship between emotions and ethics is highly intricate [20]. Yet, as Bloom [18] states, “[e]motional responses alone cannot explain one of the most interesting aspects of human nature: that morals evolve.” Research has actually shown for instance that people in general are more compassionate now than 100 years previously [21], but we are also more judgmental. The capacity of sympathy, and quite arguably, empathy has expanded, and people overall have greater understandings for social, racial, gender and sexuality-related issues than they had previously. This is owed greatly to the increase and accessibility of debate and rational deliberation that has increased awareness and information about not only how the issues exist on societal levels, but also how they impact on the individual lives that they affect.

2.3 Tight Link Between Technology and Ethical Stance

A substantial part of this information landscape through which people have access to data and broad, varying viewpoints is facilitated by the Internet and its supported and supporting technology. A tight link is apparent between the types of technology that are available, how easy they are to use and how closely it connects to our everyday lives, and what types of information and affordances (the things these technologies can do for us, see e.g., [22, 23]) the technology offers, in relation to what information people encounter, how they encounter it and how it fits in the schema of their lives. Fromm this perspective, we may consider that the Internet covers and applies to every area of any individual’s life, from dishwashing to sex. Incidentally, one area of ethics that has been highly sensitive and vulnerable to debate is the matter of sex - also known as sexual ethics [24]. Sexual ethics can be understood in part as a sub-category of bioethics, in which scholars seek to explain the meaning of sexuality, as well as cause and effect relationships of sexual activities, orientations and attitudes. Sexual ethics additionally includes debate concerning disease and dysfunction, design versus obligation, justice versus purity. Here, emphasis is placed on establishing standards for intervention in physical processes, human rights and particularly self-determination, human growth ideals, and the critical role of social context on determining interpretation and regulation of sexual behavior.

Thus, the ethical layers posed by not only technology, its design and experience, but also by its use within other ethically challenging domains such as sex, forces researchers and developers alike to consider the diverse aspects that can influence and affect people’s quality of life and societal health in general. Raising awareness of ethical questions relating to sex technology - sex robotics, toys and sexually-orientated social media (which additionally accrue further ethical questions, see, [25]). Yet, to understand the scope of these discussions, we need to see how sex-related technology has emerged and developed.

3 Evolution of Sex Tech - from Embodied to Social Media to Embodied Interactions

In this section we describe sex tech, what it means in the context of social media and embodied interactions and intelligent systems, and how its framing has evolved through the history of the Internet. Mark Davis [26] refers to the rise in sex tech consumption through the lens of technosexuality. Davis argues that the levels of technosexuality have risen along with the infiltration of the Internet, and the Internet’s developmental history itself. In fact, the link between sex and the Internet is so strong that we may observe it through the French Minitel computer network in the 1980s [27]. During Minitel’s early development even it was noted that the economic viability of the technology was held in its ability to facilitate distanced dating. Thus, through its very birth, the Internet has been strongly socially and economically connected to sex and sexuality. Sex and matchmaking has driven the technological development of the Internet and its associated industries [27]. The focus has evolved though from direct human to human communicational connections, to enveloping the spectrum of human sexual fantasies [28]. This matter is particularly important to remember when considering the connections between future technology vision and popular culture. For as seen in movie classics such as The Lawnmower Man (1992) and the more recent WestWorld (2016-onwards), there is an intricate link made between intelligent technology development, power through intelligence and desire, human-machine synthesis and moral grounding (ethics - ethical conduct) (see also, [29]). In other words, what does the desire for power, control and the sexual objectification of technology and through technology say about the core nature of humanity?

This matter has been taken up in the field of cultural studies, particularly in light of the troubled relationship between (sexed) human bodies and machines that represent great super power in popular culture [30]. In fact, the spectacle of cybernetic (organic-artificial) couplings of human flesh to technology is seen as a cultural, societal and arguably emotional reaction to transitional periods, especially those characterized by ‘post’ - the migration from industrialism to post-industrialism; reality to post-reality; modernity to post-modernity; human to post-humanity. We can also understand this cybernetic coupling through a different lens such as the history of sex toys, dolls and other technology. Thus, to broaden the scope we may see that technosexuality includes a wider range of technology, from biotechnology and drug manufacturing, to gadgets, toys and simulations. To begin with, sex technology itself as seen in sex dolls and other devices go back through human history [31]. Some examples in relatively modern history can be seen in the instances of cloth or sack effigies known as dames de voyage that were used by lonely sailors on their long voyages [32].

A dames de voyage in its simplicity may not have posed too much complexity in its need, design and use from perspectives such as ethics. A fairly simple, maybe decorated sack, hardly could have been mistaken for a human through its life-likeness. The physical, embodied sack was an intimate companion to sailors who were limited to the confines of the ship and the company of other sailors. From historical ethical stance, as well as religious and moral views towards homosexuality, for instance, the dames de voyage would have been the preferred option. Perhaps, the treatment of the dames de voyage may have generated a myriad of extra questions, and those are interesting for exploration in further papers. What is paramount here is not only the improvements to fidelity and quality of sex technology on offer - from dismembered and/or novel artificial body parts with multiple functions to sex robotics - but the ways in which these technological advancements, including the nature of intimate encounters through social (sex) media (e.g., Tinder) change the way in which we view sex. From an ethical standpoint, what is of particular concern is how the use and experience of these technologies change the ways in which we treat other people. From this vantage point then indeed we are delving into the field of how people understand and/or abide by moral principles - our ethical stance. Because it is through this ethical stance that we formulate a code of conduct via which we interact with, treat, experience and conceptualize other people in relation to ourselves [18]. For this reason, intentionality is pivotal in comprehending human consciousness and motivation, particularly when ascertaining how people position themselves in terms of ethical stance [33].

3.1 Intentionality, Ethical Stance and Technosexuality

To illustrate the role of intentionality within ethical stance and how people use technology for sexual purposes, we may observe that the historical dames de voyage may have been used as a tool to stand in for, or indeed substitute, one’s marital partner. In the sailor’s mind, the sack may have been the wife herself, and/or it was used as a tool to curve temptation in relation to engaging in a relationship outside of the marital institution. Likewise, sex toys could be seen as a means of substitution in the absence of intimate relationships, and/or enhancers for these relationships. Sex robots and their development have been discussed in great detail, particularly for this function - of substituting live partners [32, 34, 35] or curbing sexual deviance (i.e., pedophilia, see e.g., [36, 37]). Once again however, it may be questioned as to: a) whether or not sexual preditorism should be condoned through providing technologies that support this behavior; and b) how the use of technology in these ways further desensitizes the individual to the feelings and wellbeing of others. Where we continue this journey into deep murky waters, or the ethically unclear domain of ‘healthy’ or ‘correct’ human-sex robot relationships, has been when people begin to prefer being with a sex robot, and/or people who are already in relationships with human beings still engage in sex with robots [37].

This challenge does not simply belong to the domain of robotics, for the engagement of married humans with life-like sex dolls has also attracted the same types questions [34, 38]. Can engaging in intimate activities with technology be considered as adultery? Perhaps, in a similar way, while maybe not engaging directly in sexual activity per se, but extra-marital interactions between individuals on social media have also raised the same questions. Can flirtation or deep intimate discussion online with others outside the immediate marital/legal relationship be considered as adultery? What is acceptable in interaction - either directly with technology or other humans through technology - and what is not? How has the nature of social media, and particularly the development and popularity of Apps such as Tinder, Bumble and Match.com changed people’s attitudes towards what is acceptable (socially and ethically) in online-offline interaction and what is not?

4 Sex Technology and Ethics

In fact, while sex toys and devices have played significant roles in our personal lives, there has been very little research specifically focusing on these technologies [32, 39]. The cousin domain of pornography has received considerable attention in recent times, yet, sex toys, dolls, robots and other sex-orientated technology have been relatively forgotten. With this said, the scarce research that is available, attempts to investigate the domain from the perspectives of sexual products, uses, users and outcomes. Döring and Pöschl [39] in particular, review research on sex technology through combining three distinct frameworks: 1) the positive sexuality framework [40]; 2) the positive technology framework [41]; and 3) the positive psychology approach [42]. Their argument was that sexual products could enable the improvement of sexual wellbeing in society. From the outset Döring and Pöschl’s initiative can be seen as a practical move towards establishing an ethical code of conduct for sex technology, its use and experience.

Interestingly, while Döring and Pöschl focused on sex technology from a practical perspective of sexual wellbeing, several ethical issues automatically arose even without being labelled as such (see Fig. 2). Firstly, they mention that the consumption of female and even sex robots with child-like resemblances may lead to the objectification of real women and children by users [43, 44]. This links to observations made above whereby deviant sexual behavior may increase through high engagement in fetishes and paraphilias that can reduce inhibition [45]. Secondly, human loneliness and social anxieties may increase in connection to other human beings through people isolating themselves with sex technology and particularly sex robots [46]. Thirdly, quite fascinating is Döring and Pöschl’s point on sex robots potentially reducing levels of prostitution, sex trafficking and indeed adultery [47]. The issue on sex trafficking is one matter that remains to be seen. Yet, the other two matters - prostitution and adultery - open the door to further debate. Firstly, focusing on adultery and as we query above - how do we define it? Is it simply the case of a partner being unfaithful to their spouse through engaging in relations with another human? Or can intimate engagement with a machine also be considered adultery? This is particularly if one’s thoughts, actions and intentions become fixated on and directed to the machine and the ideals that the human holds regarding this technology. Secondly, would reduced consumption of prostitution generate outrage and concern for robotics taking over jobs as is heavily discussed in other industrial fields? Will sex robots replace prostitutes and render millions of human professionals without income?

On this note, and to step the ‘robots will take our jobs’ debate one more notch, we may consider, what at the end of the day is actually the most desirable sexual toy for humans - machines or real, organic human beings? Then, with this line of thought, and looking back towards the synthesis of humans and technology we may look at what dating (or instant sex) Apps are actually doing in practice. For, as with porn and the Internet enabling free access to pornographic material at any time of the day and anywhere, can we not see that Apps such as Tinder (and even Facebook) are doing the same thing to the field of prostitution. Why would people pay a prostitute for gratification, if they can get the same service if not more for free through a dating App [38, 48]? Then, once more from the humanitarian perspective of ethics: do dating Apps simply reinforce the objectification of other human beings? This is particularly in light of the fact that in monogamous relationships, humans with either good ethical intention or deviant intentions usually need to devise social strategies for sustaining their relationships [49]. This may be through violence or manipulation, yet it also may be through good, fair and equal treatment and reciprocal relations with their partners. Especially empathy and the ability to feel the partner’s emotions and concerns is critical for sustaining a healthy and meaningful relationship. In the case of sexual behavior existing in chains of fleeting intimate interactions that have been mediated by the Internet, what is the incentive for people to take the time to acknowledge and respect the dating App match in terms of the entire human being that they are? This is where concerns for empathy or the lack thereof relay human-to-human dating App interactions to the same category of human-robot sex interactions [50,51,52,53].

5 Evolving Sexual Technology and Ethical Stance

In understanding these dynamics, and particularly the prominence and popularity in modern Western societies of Apps such as Tinder, it is highly crucial to consider whether or not human beings’ ethical stance has changed and in what ways. Would Tinder, and/or actions implicated in the contemporary use of dating Apps have been acceptable and as openly discussed maybe 15 to 25 years ago? Moreover, consideration needs to be made in regards to how the Internet, its social-cultural evolution and materialization (digitalization) of human fantasies through any times of information imaginable, have unleashed the dark sides of humanity and what religion and law have been trying to regulate and structure for thousands of years [54]. Over the last few centuries intensive debate and scholarship has focused on the dynamics between ethics and morality. In relation to the Internet for instance, Schultz [55] characterizes ethics as principles that seek to regulate cooperative burdens and benefits. Morality, on the other hand, he describes as comprising principles that are established and reinforced by cultural and religious beliefs. Schultz argues that ethical problems relating to the Internet are greatly contingent on principles regarding individuals, societies as well as social and economic matters. Moreover, from this perspective we can see that ethical concerns induced by Internet use and its nature are primarily founded in individual and social dimensions.

On a formal ethical level, we may draw on the traditions of intuitionism, utilitarianism, and universal principle [56]. Intuitionism is a means of explaining ethics through feelings and from Hume’s [56] perspective, emotions. Within intuitionism, there are no formal classifications or standards, ethical processes and definitions are more intuitively derived. Regarding utilitarianism, ethical stance is the impulse to engage in the ‘right’ or correct action in order to maximize benefit or provide the greatest good for the largest number of people (parties). According to the universal principle of ethics, people act according to principles that may be considered universal law, or as could otherwise be known as ‘social contract’ [57]. Immanuel Kant [58] for instance established an understanding of universal ethical principles that may be seen as the foundations of society and civil means of behavior. One example can be seen in relation to credit. If people in general had no intention of paying credit card debts the entire credit system would not function. This relates to what Kant termed as ‘Categorical Imperative’ whereby people act according to principles that are somehow deemed as universal law. A more ancient example of this can be seen in the Golden Rule that dictates that people should treat others in the ways that they wish to be treated themselves [20].

The matter of Internet ethics is said to concern three main aspects - the individual, the social and the global [59]. Yet, through deeper understanding of the psycho-social composition of the individual, and indeed self, we may ascertain that the self is always social (this is how the self is defined - in relation to others) [59]. This self, through the Internet, is by default global on many levels. But this characteristic between the self and others - how the I self, the part of us that understands on some level how we are positioned and relate to society and the Me self, our self-image, self-concept, self-schemata (how we imagine and desire ourselves to be) [60] - is what drives our behavior and conscious awareness of the impacts of this behavior in online spaces. Business in particular, is driven by self desire. What generates interest and feeds this desire, is what makes money from the business perspective. Arguably, despite efforts regarding business ethics and current trends in ethical business (social responsibility etc.) deep-seated desire through sexual fantasy that both gratifies the body and validates the self still is hard to resist from the business perspective. As has been observed, the Internet has radically changed not only human-human interactions, but also business models. What once required someone to reach into their pockets to extract money in exchange for services and encounters, not exists within the walls of Internet infrastructure and the surveillance economy - data as currency. This in turn, poses more ethical questions in the discussion of human-technosexual consumption.

From the perspective of sex and technology, research has revealed a tight link between technological advancement and sexual behavior [61]. Modes of courtship shifted from being facilitated by families to being more casual, individualistic and sexually oriented [62]. When looking historically at technological development, we may observe that cars and the entertainment industry were strong enablers in the liberalization of sex during the twentieth century [61]. This was afforded by transportation and spaces (drive-in practices, movie theatres and dance halls for instance) where youth and younger adults could escape the control of their parents. The innovation of the Internet, or world wide web (WWW) opened up physical boundaries to allow more people over vast distances to interact with one another [61]. Thus, many of these technology related questions have been about accessibility and opportunity. Interestingly, Daneback and colleagues [63] empirically studied this matter through examining the relationship between private Internet access versus public. Their study showed that people were more willing to engage in sexually related online material via private Internet access than they were through public Internet access. This seems logical, but what rests at the heart of this paper is the change of inhibition relating to sex that has emerged through human-technology interaction. Timmermans and Courtois’ [61] Belgium-based study of Tinder users revealed that despite the critique that dating Apps such as Tinder had received particularly regarding casual sex, only relatively small amounts of online interactions had resulted in casual sex. In fact, their questionnaire of 1038 Tinder users demonstrated that only half of the online interactions resulted in offline meetings. Then, of these offline meetings, only one third of them resulted in casual sex. Interestingly, their study revealed that women were more likely to engaged in casual sex, which is contrary to a wealth of research that suggests otherwise (i.e., see [64,65,66]).

Moreover, in reference to the above description of ethical principles and particularly understandings of social contract and individual-social (self and other) contingencies, it can be seen that cultural conventions and framing play a major role in the interpretation and application of services such as Tinder [66]. Tinder was promoted as an effective hookup tool [66], and has then subsequently been adopted as a cultural object as such. This means that the object in itself attracts the attention of users who are seeking to engage in the technology for casual sexual purposes. It also means that the register of language and ways in which people interact with one another through these services have a slant and higher tolerance for interaction of a sexual nature. Maybe more than simply analyzing human interaction with sexual technology, or sexual interaction through technology, in terms of ethical stance, we may instead observe these developments through the lens of evolving understandings of human sexual relationships. During the past century alone there have been fragmentations and re-configurations of cultural frameworks defining love relationships. There was a move, for instance from ‘romantic love’ - lifelong commitment to one partner - to ‘pure’ or ‘confluent love’ [10]. In romantic love there is the search for the ideal partner, emphasizing monogamy for the rest of one’s life, whereas in confluent love there is the aspect that people seek partners for perfect relationships in which both parties experience equality and satisfaction in all respects. In the confluent love scenario, mutual benefit needs to be sustained throughout the duration of the relationship. As soon as this benefit or satisfaction starts to dwindle, it is time to move on to seek the next ideal partner. In this model monogamy is still a trait of the relationship, yet the relationship is only as long as the satisfaction within it is sustained by both partners [10]. This mode of love is contingent upon a number of factors such as values, identities and interests [67].

The role of technology here can be seen on the micro-social level as influencing human-to-human interactions and experiences of other humans through design affordances [22, 23, 65]. The technical features, functions, materials, social and aesthetic properties, all play a part in facilitating interaction and experience. Where it is through the immediacy of online dating platforms, or through the realism and lack of objection from a sex doll or robot, the technology guides the ways in which we can interact with it and through it. A key design quality of Tinder for instance, is not only that it enables the arrangement of offline encounters, but it also facilitates multiple interactions simultaneously with many prospective sexual partners [68].

6 Conclusion

Just because an action is afforded by technology - be it available online content (pornography), social media or robotics - does it make it right? Once again we need to return to the questions of what is the right action? And, how can we ensure the greatest benefit for the most parties? Timmermans and Courtois [61] cite numerous studies in which particularly women benefit from casual sexual encounters such as those mediated by Tinder. In fact, a lot of research has also shown the benefits of pornography viewing [69]. Yet, the actional, interactional and experiential networks represented in the supply and consumption ecosystems of these products still need to be accounted for when taking an ethical stance. For instance, while pornography viewing experience can be beneficial on a number of social, psychological and sexual levels, how does it stand in relation to supply? When thinking of supply we are thinking of the lived conditions of the ‘actors’ shown within the content, how well they were paid, how safe and well looked after they are, and whether or not they actually have given full consent to the published content [70]. From this perspective there may indeed be inequalities from the viewpoint of human rights, and this also needs to be taken into account - not simply because of the immediate conditions of the ‘actors’, but also in terms of the social conditioning of the viewers and how they go on to treat others in subsequent interactions.

In the immediate instance of online-offline sexual encounters with other humans, it needs to be considered as to whether or not anyone will be hurt (physically, socially or psychologically), and how these encounters impact people and relationships surrounding the individuals engaging in the activity. There is then the subsequent ‘ripple effect’ of broken families for instance, mental health problems (depression, suicide, low self-worth), unemployment, substance abuse to name some. Then from a business and society perspective, if anyone does get hurt, there needs to be an understanding of who or what party should be held responsible. Since the Trump win of the 2016 United States elections, accountability and responsibility in tech business has been of major concern due to the role of fake news in influencing the elections. Thus, if responsibility and accountability is held by the corporate organizations facilitating the technology that enables these interactions, there should be clear ethical guidelines developed that seek to avoid and/or mitigate the problems arising from these interactions.

Then, there are the larger societal and economic considerations that were raised above relating to the roles of random partners in online-offline sexual interactions and sex robots and whether or not they can be seen as threats to the professional workforce and industry of prostitution. While these cultural configurations and re-configurations of sexual encounters and partnerships can be defined as cultural, within this viewpoint we can understand that ethics are structured by socio-cultural normative frames. There is a tight link between economics, technological development and use that sees people and culture evolve not only in behavior but also in thought and belief. In light of many of the issues raised in this paper, particularly in relation to the Pygmalion question - in the future, is what we are looking for really human-to-human relations through sex, or will we be happier when we are engaging with Tinder playing sex robots?

References

Ovidius (Ovid) Naso, P.: Pygmalion and the statue. In: More, B. (ed.) Metamorphoses. Cornhill Publishing, Boston (1922)

Mitchell, T., Daniels, D.: Motivation. In: Borman, W.C. Ilgen, D., Klimoski, R. (eds.) Handbook of Psychology, vol. 2, pp. 229–254. Wiley, Hoboken (2003)

Raudenbush, S.: Magnitude of teacher expectancy effects on pupil IQ as a function of the credibility of expectancy induction: a synthesis of findings from 18 experiments. J. Ed. Psych. 76, 85–97 (1984)

Giddens, A.: The Transformation of Intimacy. Polity, Cambridge (1992)

Fieser, J.: Ethics. Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy (2020). https://iep.utm.edu/ethics/

Duncker, K.: Ethical relativity? (An enquiry into the psychology of ethics). Mind 48, 39–57 (1939)

Moor, J.K.: Reason, relativity, and responsibility in computer ethics. ACM SIGCAS Comput. Soc. 28, 14–21 (1998)

Lindebaum, D., Geddes, D., Gabriel, Y.: Moral emotions and ethics in organisations: introduction to the special issue. J. Bus. Ethics 141(4), 645–656 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3201-z

Svensson, G., Wood, G.: A model of business ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 77(3), 303–322 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9351-2

Gališanka, A.: Just society as a fair game: john rawls and game theory in the 1950s. J. Hist. Ideas 78, 299–308 (2017)

Seay, S.: Sustainability is applied ethics. J. Leg. Eth. Reg. Is. 18, 63–70 (2015)

Martin, K.: Ethical Implications and Accountability of Algorithms. J. Bus. Ethics 160(4), 835–850 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3921-3

Aström, T.: Moral Positioning: A Formal Theory. Ground. Theory Rev.: Int. J. 6, 29–59 (2006)

IGI Global: Ethical Stance. Dictionary. https://www.igi-global.com/dictionary/ethical-stance/37711#:~:text=1.,to%20be%20right%20and%20true. Accessed 18 Jan 2021

Ryan, T.: Teaching and technology: issues, caution and concerns. In: Handbook of Research on New Media Literacy at the K-12 Level: Issues and Challenges (2009)

Seeley, J.: The making and taking of problems: toward an ethical stance. Soc. Probs. 14, 382–389 (1966)

Aström, T.: In the force field of handicap. moral positioning and theory of social positioning. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Stockholm (2003)

Bloom, P.: How do morals change? Nature 464, 490 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/464490a

Farber, P.: The Temptations of Evolutionary Ethics. Uni. of California, Berkeley (1994)

Saariluoma, P., Rousi, R.: Emotions and technoethics. In: Rousi, R., Leikas, J., Saariluoma, P. (eds.) Emotions in Technology Design: From Experience to Ethics. HIS, pp. 167–189. Springer, Cham (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-53483-7_11

Haslam, N., McGrath, M., Wheeler, M.: Changing morals: we’re more compassionate than 100 years ago, but more judgmental too. World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/03/changing-morals-we-re-more-compassionate-than-100-years-ago-but-more-judgmental-too/. Accessed 21 Jan 2021

Gibson, J.: The concept of affordances. Perceiving, acting, and knowing 1 (1977)

Norman, D.: The way I see IT signifiers, not affordances. Interactions 15(6), 18–19 (2008)

Encyclopedia.com: Sexual ethics. https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/sexual-ethics. Accessed 18 Jan 2021

Condie, J., Lean, G., Wilcockson, B.: The trouble with Tinder: the ethical complexities of research location-aware social discovery apps. In: The Ethics of Online Research. Advances in Research Ethics and Integrity, vol. 2, pp. 135–158. Emerald Publishing, Bingley (2017)

Davis, M.: Sex, Technology and Public Health. Springer, Cham (2008). https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230228382

Castells, M.: The Rise of the Network Society, 2nd edn. Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken (2009)

Paasonen, S.: Labors of love: netporn, Web 2.0 and the meanings of amateurism. New Media Soc. 12(8), 1297–1312 (2010)

Rousi, R.: Me, my bot and his other (robot) woman? Keeping your robot satisfied in the age of artificial emotion. Robotics 7(3), 44 (2018)

Botting, F.: Sex, Machines and Navels: Fiction, Fantasy and History in the Future Present. Manchester University Press, Manchester (1999)

Cheok, A.D., Zhang, E.Y.: Sex and a history of sex technologies. In: Cheok, A.D., Zhang, E.Y. (eds.) Human-Robot Intimate Relationships, pp. 23–32. Springer, Cham (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94730-3_2

Ferguson, A.: The Sex Doll: A History. Tangney & Fischer, McFarland (1995)

Ellsworth, P., Scherer, K.: Appraisal processes in emotion. Handbook of Affective Sciences 572, V595 (2003)

Döring, N., Mohseni, M.R., Walter, R.: Design, use, and effects of sex dolls and sex robots: scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 22(7), e18551 (2020)

Levy, D.: Love and Sex with Robots: The Evolution of Human-Robot Relationships. HarperCollins, New York (2009)

Danaher, J.: Regulating child sex robots: restriction of experimentation? Med. Law Rev. 17(4), 553–575 (2019)

Danaher, J., McArthur, N. (eds.): Robot Sex: Social and Ethical Implications. MIT Press, Cambridge (2017)

Kolivand, H., Ehsani Rad, A., Tully, D.: Virtual sex: good, bad or ugly? In: Cheok, A., Levy, D. (eds.) LSR 2017. LNCS (LNAI), vol. 10715, pp. 26–36. Springer, Cham (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76369-9_3

Döring, N., Pöschl, S.: Sex toys, sex dolls, sex robots: our under-researched bed-fellows. Sexologies 27(3), e51–e55 (2018)

Williams, D.J., Thomas, J.N., Prior, E.R., Walters, W.: Introducing a multidisciplinary framework of positive sexuality. J. Positive Sex 1, 6–11 (2015)

Riva, G., Banos, R.M., Botella, C., Wiederhold, B.K., Gaggioli, A.: Positive technology: using interactive technologies to promote positive functioning. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 15(2), 69–77 (2012)

Seligman, M.E.P., Csikszentmihalyi, M.: Positive psychology: an introduction. Am. Psychol. 55(1), 5–14 (2000)

Döring, N.: Vom Internetsex zum robotersex: forschungsstand und herausforderungen für die sexualwissenschaft [From Internet sex to robot sex: state of research and challenges for sexology] Z Sex-Forsch 30(01) 35–57 (2017)

Richardson, K.: Sex robot matters: slavery, the prostituted, and the rights of machines. IEEE Tech. Soc. Mag. 35(2), 46–53 (2016)

Sharkey, N., van Wynsberghe, A., Robbins, S., Hancock, E.: Our sexual future with robots - a foundation for responsible robotics consultation report (2017). Foundation for Responsible Robotics, The Hague. http://responsiblerobotics.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/FRR-Consultation-Report-Our-Sexual-Future-with-robots_Final.pdf. Accessed 21 Jan 2021

Sullins, J.P.: Robots, love, and sex: the ethics of building a love machine. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 3(4), 398–409 (2012)

Yeoman, I., Mars, M.: Robots, men and sex tourism. Futures 44(4), 365–371 (2012)

White, N.: ‘The industry is dying out’: Madam claims dating apps like Tinder are taking away brothels ‘bread and butter’. Daily Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-4258556/Tinder-killing-brothels-taking-best-customers.html. Accessed 25 Jan 2021

Brunell, A-B., Campbell, W.K.: Narcissism and romantic relationships. In: The Handbook of Narcissistic Personality Disorders: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Findings and Treatments, pp. 344–350. Wiley, Hoboken (2017)

Bhattacharya, S.: Swipe and burn. New Sci. 225(3002), 30–33 (2015)

Hardey, M.: Mediated relationships . Inf. Commun. Soc. 7(2), 207–222 (2004)

Landovitz, R.J., et al.: Epidemiology, sexual risk behavior, and HIV prevention practices of men who have sex with men using GRINDR in Los Angeles, California. J. Urb. Health 90(4), 729–739 (2013)

Sales, N.J.: Tinder and the dawn of the ‘Dating Appocalypse’. Vanity Fair (2015). http://www.vanityfair.com/culture/2015/08/tinder-hook-up-culture-end-of-dating. Accessed 18 Jan 2021

Rosenzweig, R.: Wizards, bureaucrats, warriors, and hackers: writing the history of the Internet. Am. Hist. Rev. 103(5), 1530–1552 (1998)

Schultz, R.A.: Contemporary Issues in Ethics and Information Technology. IRM Press, Hershey (2005)

Hume, D.: An enquiry concerning the principles of morals. In: Schneedwind, J.B. (ed.) Moral philosophy from Montaigne to Kant. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge [1751] (2002)

Brownsey, P.F.: Human and the social contract. Philos. Quart. 28(111), 132–148 (1978)

Kant, I.: Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Ethics. Green and Co., London (1895). T. Kingsmill Abbott (trans.)

Neisser, U. (ed.): The Perceived Self: Ecological and Interpersonal Sources of Self Knowledge 5. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2006)

James, W.: The self. In: Baumeister, R.F. (ed.) Key Readings in Social Psychology. The Self in Social Psychology, pp. 68–77, Psychology Press, Hove (1999)

Timmersmans, E., Coutois, C.: From swiping to casual sex and/or committed relationships: exploring the experiences of Tinder users. Inf. Soc. 34(2), 59–70 (2018)

Illouz, E.: Consuming the Romantic Utopia: Love and the Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. University of California Press, California (1997)

Daneback, K., Månsson, S.A., Ross, M.W.: Technological advancements and Internet sexuality: does private access to the Internet influence online sexual behavior? Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 15(8), 386–390 (2012)

Grello, C.M., Welsh, D.P., Harper, M.S.: No strings attached: the nature of casual sex in college students. J. Sex Res. 43(3), 255–267 (2006)

Hjarvard, S.: The Mediatization of Culture and Society. Routledge, Oxon (2013)

Duguay, S.: Dressing up Tinderella: interrogating authenticity claims on the mobile dating app Tinder. Inf. Commun. Soc. 20(3), 351–367 (2017)

Gross, N., Simmons, S.: Intimacy as a double-edged phenomenon? An empirical test of Giddens. Soc. Forces 81(2), 531–555 (2002)

LeFebvre, L.E.: Swiping me off my feet: explicating relationship initiation on Tinder. J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 35, 1–17 (2017)

Rissel, C., Richters, J., De Visser, R.O., McKee, A., Yeung, A., Caruana, T.: A profile of pornography users in Australia: findings from the second Australian study of health and relationships. J. Sex Res. 54(2), 227–240 (2017)

Albury, K., Crawford, K.: Sexting, consent and young people’s ethics: beyond Megan’s Story. Continuum 26(3), 463–473 (2012)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the University of Jyväskylä and Business Finland for funding this research, and particularly Professor Pekka Abrahamsson and his AI Ethics research group for supporting this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Rousi, R. (2021). Ethical Stance and Evolving Technosexual Culture – A Case for Human-Computer Interaction. In: Rauterberg, M. (eds) Culture and Computing. Design Thinking and Cultural Computing. HCII 2021. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 12795. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77431-8_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77431-8_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-77430-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-77431-8

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)