Abstract

A discussion of professionalism and professionalisation of the role of outdoor environmental educator (as distinct from the role of outdoor activity leader) is undertaken as a prelude to the debate about whether higher education (HE) graduates should engage in practices that demonstrate professional currency. Professional currency for outdoor and environmental HE graduates is described as maintaining skills and knowledge for professional practice for the role of outdoor environmental educator. There is evidence that outdoor environmental education (OEE) is a recognised profession and discipline, however aspects of professional status are yet to be resolved. The current situation for the professionalisation of OEE is compared with two other recognised professions, teaching and occupational therapy. Examples of, and rationales for, professional currency practices for HE graduates of OEE are explored.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Professional currency is a term used to describe maintaining skills and knowledge for professional practice. This intent of this chapter is to begin a conversation about professional currency for graduates of Higher Education (HE) programs. The frame of reference is the Australian context of outdoor environmental education, where the accepted term for a professional in this field is ‘outdoor educator’ (Thomas et al., 2019). ‘The Fremantle Declaration’ (Meredith, 2010, p. 6) provides one framework for professional practice developed at the 2010 Australian National Outdoor Education Conference:

Outdoor education provides unique opportunities to develop positive relationships with the environment, others and ourselves. These relationships are essential for the wellbeing and sustainability of individuals, society and our environment. (Meredith, 2010, p. 6)

This chapter begins with a discussion about the current status of outdoor environmental education as a profession, with particular reference to the Australian context. International examples of professional recognition and practices in demonstrating professional currency in outdoor environmental education are explored before investigating selected examples of other professions. The chapter concludes with a discussion about the future of outdoor environmental education professional currency recognition.

1 Professionalism and Professionalisation in Outdoor and Environmental Education

Professional currency is demonstrating current knowledge and capability for professional practice. It might also be interpreted as avoiding ‘professional obsolescence’ (Ferdinand, 1966 in Clayton et al., 2011), with a ‘discrepancy between job performance and an expected level of competence’ (Chauhan & Chauhan, p. 1, in Clayton et al., 2011, p. 3). Professional currency demonstrates professionalism in a chosen field of endeavour.

There are potential benefits to HE graduates in maintaining professional currency. Murray and Lawry (2011), when interviewing professional Occupational Therapists about their perceptions of maintaining professional currency, conclude that professional currency assists with promoting self-determination, raising perceptions of professional capacity and positively impacting the workplace, encouraging working with others and encouraging professional and personal self-care (Murray & Lawry, 2011).

Professionalism can be a values system able to contribute positively to both members of the profession and to society. However, it can also be an ideology that seeks to impose a belief system a mechanism of control to increase status, income and upward mobility. Professionalism potentially can narrow the field of endeavour and create barriers to alternative ways of thinking and discourage creativity. The process of professionalizing outdoor and environmental education has the potential to positively influence the dominant narratives about professional practice, however may curtail the focus on innovations.

Cautions about professionalism and professionalization of outdoor and environmental education are not new. For example, in Ford (1986):

There is no nationally standardized outdoor education curriculum and no nationally standardized measure of outdoor education competency or knowledge. Outdoor education programs are sponsored by elementary and secondary schools, colleges and universities, youth camps, municipal recreation departments, and private entrepreneurs. They exist in every geographic location and are administered by people of widely varied backgrounds. There is no single body of outdoor professionals in outdoor education because the field transcends school boundaries into recreation departments, youth-serving agencies, conservation organizations, resource management agencies, and many other facets of society. As a result, outdoor education is viewed from different perspectives. (Ford, 1986, p. 1)

Brookes (2004) is critical of any approaches to narrow the field of outdoor and environmental education. He examined attempts to define the body of knowledge through education curriculum and textbooks and warned:

Universalist or absolutist approaches are not helpful in Australia. If there is a lesson from Australian environmental history over the last two centuries, it is surely that if there is a need for outdoor education, it can only be determined by paying careful attention to particular regions, communities, and their histories. In Australia at least, approaches to outdoor education theory, which try to eliminate or discount differences between societies and communities, cultural differences, and geographical differences, are seriously flawed. (Brookes, 2004, p. 32)

Potter and Dyment (2016) summarising from an earlier article in 2015, explore the claims of outdoor education to be a discipline and suggest that great progress has been achieved in three of six of the components listed by Liles et al. (1996, in Potter & Dyment, 2016). These components are: a focus of study; a worldview or paradigm; and an active research or theory development agenda. In their view, the three areas that remain under-developed are: a lack of strategic and systematic approach to the promotion of professionalism; a lack of clarity about reference disciplines; and a lack of clarity about principles and practices.

In Australia, Martin (2003) identified five ‘signposts towards a profession’ in his consideration of outdoor education and its development towards this status. He compared outdoor education with other fields such as nursing and physiotherapy and their path to becoming recognised and distinct allied health professions. Arguably the profession of outdoor and environmental education in Australia has arrived at a destination for at least two of these ‘signposts’ (1 and 3, below) and have made some progress for the other three. Likely it is a similar situation for a number of other countries.

-

1.

‘A motive of service beyond self- interest’

Building on the work of Martin and others a ‘green paper’ was released, summarizing the ‘issues, directions, and priorities from the Australian national outdoor education “Bendigo Summit 2001”’ (Kiewa, 2003, p. 11) with nine goals for outdoor education in Australia. Goal One was “Clarify and interpret the motive of service of the outdoor education profession” (Kiewa, 2003, p. 11) with conference attendees achieving agreement about ‘The Motive of Service’ declaration:

Through interactions in the natural world, Outdoor Education aims to develop an understanding of our relationship with the environment, others and ourselves. The ultimate goal is to contribute towards a sustainable world (Kiewa, 2003, p.12)

-

2.

‘Development of a specialised body of knowledge’

Although contentious, there are emerging academic works that support the view that outdoor education has both a broad and specialised body of knowledge (Potter & Dyment, 2016; Thomas et al., 2019) and that outdoor educators require specific skills and knowledge beyond the field of outdoor recreation (Thomas et al., 2019).

However, outdoor and environmental education has not developed a shared scope of practice or clear minimum thresholds for graduates, an important milestone for other emerging professions such as Physiotherapy, Exercise Science and others. Recent efforts by the Australian Tertiary Outdoor Education Network (Thomas et al., 2019) to address a shared understanding between Australian universities lay the foundation for a development of such a scope of practice for the role of ‘outdoor educator’ in the future.

-

3.

‘A code of ethics’

Following the Bendigo Summit in 2001, Griffith University Masters of Outdoor Education student Innes Larkin undertook a multi-stage consultation process to arrive at what is now accepted as the Australian Code of Ethics for Outdoor Educators.

-

The outdoor educator will fulfil his/her duty of care.

-

The outdoor educator will provide a supportive and appropriate learning environment.

-

The outdoor educator will develop his/her professionalism.

-

The outdoor educator will ensure his/her practice is culturally and environmentally sensitive. (Larkin, 2003)

-

4.

‘Admission to profession’

In Australia, outdoor environmental education is a profession that slips between the cracks at present. Unless the individual is a teacher, psychologist, social worker or other accredited professional, outdoor educators are not required to demonstrate minimum capabilities for a professional role or to demonstrate currency to a registering body. Other recognised professions require completion of an accredited higher education program and demonstration of capability to practice as an entry level practitioner before formal admission to the profession.

-

5.

‘Public recognition’

As Potter and Dyment (2016) suggest, outdoor (environmental) education is making progress towards recognition as a discipline, however without a clear scope of practice to define the specialised body of knowledge and a recognised process for admission to the profession, public recognition is highly problematic.

2 What’s Happening with Professionalism and Currency in Outdoor Environmental Education in the Rest of the World?

Two examples of professional accreditation and requirements for professional currency that encompass the role of outdoor educator provide a discursive context for professional recognition and professional currency for Australian outdoor environmental education. They are ‘Outdoor Professional’ in the United Kingdom (UK) and ‘Outdoor Educator’ in the United States (US).

In the UK, the Institute for Outdoor Learning (IOL) has devised a professional recognition process that is inclusive of a broad range of professional and volunteer roles in the outdoors. This approach is not specific to outdoor environmental education but is a clear attempt to provide pathways for professional recognition for all those working in ‘outdoor learning’. ‘The Outdoor Professional Profile’ allows recognition of all outdoor professionals working in ‘sports participation, outdoor education, youth development, wellbeing, workforce training or adventure tourism’ (IOL, 2020). ‘Outdoor Professionals provide safe activities and effective learning in the outdoors’. They have focussed on recognising ‘Values and Behaviours’ (‘values learners’, ‘values the environment’, ‘values their development’) and ‘Competencies’ (‘competent to provide safe activities and effective learning in outdoor environments’, ‘current’, ‘professional compliance’, ‘accredited’, ‘ethical’, ‘informed’, ‘connected’) (IOL, 2020). Some HE providers are accredited to provide programs that meet these professional recognition standards. Professional currency is demonstrated by continuous professional development (CPD) outlined by the manifesto ‘The Seven Steps to Continuous Professional Development’ These seven steps are summarized as (1) reflecting on motivation for CPD; (2) seeking feedback; (3) mapping current strengths; (4) deciding development goals; (5) selecting best options; (6) applying learning; (7) keeping a record. To support this learning, they provide a useful ‘Professional Development Record’ to categorize CPD according to: (1) activity skills and coaching; (2) facilitating learning; (3) outdoor leadership; (4) experience and judgement; (5) environmental knowledge; (6) professional practice. Currently, the IOL is establishing ‘Occupational Standards’ for roles that include ‘Outdoor Activity Instructor’ and ‘Outdoor Learning Specialist/Professional’ (IOL, 2020).

In the US, the Wilderness Education Association has developed a training structure with levels of recognition as ‘Certified Outdoor Leader’, ‘Certified Outdoor Educator’ and ‘Certifying Examiner’. These awards are available via Outdoor Leadership Training organisations accredited by Wilderness Education Association (WEA, 2020). Assessment is based on achieving standards in the ‘WEA 6 + 1’ (WEA, 2020) areas of judgement, outdoor living, planning and logistics, leadership, risk management, environmental integration and education. The accreditation is not specific to HE outdoor environmental education and encompasses a broad range of outdoor leadership contexts, with a ‘Certified Outdoor Educator’ endorsed to teach ‘Certified Outdoor Leaders’ rather than outdoor environmental education. Professional currency is demonstrated through completion of a professional portfolio with evidence of field experience and CPD is required to demonstrate continued knowledge and skills at the ‘WEA 6 + 1’ standards (WEA, 2020).

Both approaches are quite broad to be inclusive of outdoor environmental education and prescribe the initial standards of recognition. Each has a defined system of demonstrating currency rooted in demonstration of experience, reflective practice and professional development. Each of these systems supports Martin’s signposts. Both schemes have the potential for institutions to deliver accredited programs, with scope to register and re-register to demonstrate technical skill currency. As yet neither scheme provides explicit professional recognition and professional currency procedures for HE graduates of outdoor environmental education.

3 What Is the Professional Currency Situation in Australia Today?

The present situation for outdoor environmental education in higher education in Australia is that there is no accreditation or governing body to recognise the professional role of outdoor educator, as distinct from outdoor activity leader. Further, Marsden et al. (2012) note the absence of HE guidelines for outdoor leaders regarding the knowledge and skills for outdoor leadership, including the broader body of knowledge, skills required and practical experience. However, their discussion included a broad range of outdoor leadership roles and contexts cited by Mann (2003) including corporate development, (bush) adventure therapy, outdoor recreation, nature-based tourism and outdoor education.

Although professional recognition for the role of outdoor educator is not available it is likely that employers value evidence of current practice, with Munge (2009) surveying 32 Australian employers in the broad range of fields identified by Mann (2003) finding around 50% of respondents valued a HE background. However, employers sought other characteristics as well, including specialist (outdoor activity) knowledge, personal attributes, strong theory and philosophy as well as professional capability (Munge, 2009). Graduates from HE programs in Australia may be required to accredit in state and/or national outdoor activity leadership schemes in addition to their HE qualification to obtain employment (Polley & Thomas, 2017). Recently, the Australian Tertiary Outdoor Education Network (formed in 2016) have attempted to develop a shared understanding of what a HE outdoor and environmental education graduate knows and can do with the aim of clarifying graduate capability (Polley & Thomas, 2017; Thomas et al., 2019).

4 What Are Other Professions Doing About Professional Currency?

For most professions, formal recognition of admission to the profession involves accreditation demonstrating a graduate level of knowledge and competence. At regular intervals (1, 3 or 5 years) professionals are required to re-accredit, with graduates demonstrating development beyond beginning professional capability and verifying currency of practice for continued admission to the profession. Failure to demonstrate currency may result in debarment. Two examples of Australian professional currency are discussed here – Occupational Therapy and Teaching. Both have motives of service to contribute to society, professional recognition pathways and professional currency requirements.

Occupational Therapy (OT) formally emerged as a profession in the early twentieth century, developing professional currency standards in a broad range of contexts. Murray and Lawry (2011) discuss professional currency of Occupational Therapists and suggest:

A practitioner is professionally current if they can demonstrate engagement in some or all of the following:

-

1.

Lifelong learning by:

-

(a)

Using evidence to inform practice and clinical reasoning;

-

(b)

Updating skills and knowledge through attendance at professional development events;

-

(c)

Enrolling in and engaging in further study;

-

(d)

Participating in research activities.

-

(a)

-

2.

A reflective process to evaluate performance

-

3.

Being interested in and contributing to the development of the occupational therapy profession. (Murray & Lawry, 2011, p. 161)

Professional currency in OT requires evidence of ‘recency of practice’ with a minimum 150 h of practice within their scope of practice, 20 h of continuous professional development over the previous 12 months (or pro-rata) and meeting statutory requirements for working with clients professionally (OTCBA, 2019). Examples of professional development are provided and include HE courses, conferences, research, online learning, reflective practice journals, reviewing literature, quality assurance, professional committees and association participation, interprofessional interaction and developing capability in emerging knowledge areas (OTBA, 2019).

Teaching is probably the most aligned profession to outdoor environmental education (Potter & Dyment, 2016). Teachers graduate as probationary until completion of sufficient teaching time with endorsement from mentors of higher standing. The Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership developed Standards’ (AITSL, 2018) that are intended for use by employers and teachers to make judgements about their current stage of practice at ‘Graduate’, ‘Proficient’, ‘Highly Accomplished’ or ‘Lead’ (AITSL, 2018). The standards were developed with the involvement 6000 teachers, 120 submissions and all Australian Education Ministers. Each standard has increasing expectations of evidence for attaining them and maintaining currency grouped into three categories and seven standards. The categories are ‘Professional Knowledge’ (know students and how they learn; know the content and how to teach it); ‘Professional Practice’ (plan for and implement effective teaching and learning; create and maintain supportive learning environments; assess, provide feedback and report on student learning); and, ‘Professional Engagement’ (engage in professional learning; engage professionally with colleagues and the community) (AITSL, 2018). At re-registration teachers demonstrate professional currency with a minimum of 20 days of professional practice either as a teacher or principal at a school, or prescribed service, in Australia or New Zealand; 20 h of professional learning per year referring to the AITSL standards; along with meeting statutory requirements for working with children. Most state education departments and private schools require teachers to refer to these standards when applying for promotion. Examples of learning for teacher professional currency are on-line learning, research, conferences, seminars, participating in practice communities such as projects between clusters of schools, further study including post-graduate and certificate courses, research including reading, action research and HE study. In an evaluation of the effects of professional development for 3250 Australian teachers, Ingvarson et al. (2005) found significant impacts on content focus, active learning, knowledge and professional community.

To summarize, Teachers and Occupational Therapists have clear standards for demonstrating professional currency at re-registration. These standards include evidence of minimum experience (150 h for OT and 20 days per year for Teaching) acting in the role of a professional, demonstrating continuous development within prescribed frameworks as well as meeting statutory requirements. If a graduate outdoor environmental educator is to become a professional, then these two professions provide useful benchmarks to consider when assessing professional currency.

A common theme for graduating professionals in other disciplines such as teaching and occupational therapy is that completion of a HE degree is viewed as a foundation for entry level practice. Recency of professional practice evidenced by appropriate professional learning activities such as mentoring and being mentored, reflective practice, literature review, professional development events, professional memberships, inquiry, research, resource development and interdisciplinary learning are all activities that provide evidence of currency.

Where does this leave the graduating HE outdoor and environmental education professional? They graduate into a profession that has yet to fully demonstrate it has achieved professional status; does not have a clear mandate for practice and resists such a mandate; has not yet arrived as a discipline; has not clearly established itself as an independent profession; does not have a clearly defined scope of practice; does not have a national registration and lacks guidelines for professional currency, at least in some countries. The case for maintaining professional currency upon graduation appears, on the face of it, to be weak.

5 Future Directions

The debate about whether outdoor and environmental education should become a profession is not resolved here. Should this be the aim of outdoor environmental education to achieve public recognition through accreditation, they might choose to follow the generic advice from the (Australian) Professional Standards Councils (PSC). They describe ‘The 5 E’s of professionalisation’ as education, ethics, experience, examination and entity. Education includes currency, with a requirement for ‘on-going education or continuing professional development expectations’ (PSC, 2020). Additionally, they list 40 elements of professionalism. These 40 elements are summarized under the four themes of (1) Legislation, advocacy and responsiveness; (2) Organisational and internal governance; (3) External governance and public accountability; (4) Responsibilities and functions (PSC, 2020).

If the PSC (2020) standards are applied, then the analysis of the ‘signposts’ described earlier in this chapter confirms the profession of outdoor environmental education has made progress with more still to be done. The debate now turns to whether demonstration of professional currency has any value to the graduate. Statutory, regulatory, risk minimization, activity leadership re-registration and program requirements increase administrative load for HE graduates. Despite this lack of apparent external incentive, it is argued here that through graduates pursuing currency of practice they will benefit themselves and others. Murray and Lawry’s (2011) observation that maintaining professional currency for OT’s suggests that HE outdoroor environmental graduates may be rewarded in ways that are not easily measured such as improving graduate identity and sense of being a professional. Murray and Lawry (2011) cited benefits for professional currency as: achieving greater clarity about what further learning would enhance practice (‘self-determination’); increased knowledge about how to engage in further learning (‘perceived capacity’); improvements in practice and the broader workplace (‘workplace impact’); connecting with other professionals to support further learning (‘you need to have people around’); and, improvements in their wellbeing (‘looking after yourself’) that gave personal satisfaction and confidence. Challenges experienced by OT’s in the Murray and Lawry (2011) study included making time with heavy workloads and obtaining the support of managers.

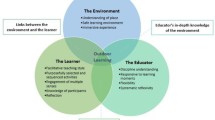

Hopefully this chapter contributes to the professional currency debate for HE outdoor environmental education positively. Teachers and learners can continue to support the development of the professional identity of graduates through involvement in professional organisations and on-going discussions about professionalism, professionalization and professional currency. Professional currency should enhance outdoor environmental education professionals’ ability to ‘provide(s) unique opportunities to develop positive relationships with the environment, others and ourselves’ (Meredith, 2010, p. 6). The pursuit of professionalism, professionalisation and professional currency may not yet have a defined end. As Michael Leunig (Fig. 30.1) suggests, the path to getting ‘there’ may not be clear when the destination is ill-defined, but we can still open the gate and head to our professional horizon.

Like any outdoor environmental education experience, it may not be the destination that provides the deep learning and intrinsic reward, but the journey to get there. It is the author’s view that HE outdoor environmental education graduate professionals will enhance the journey for others and themselves by ‘going through the gate’ and pursuing professionalism and professional currency.

Reflective Questions

-

1.

What is professional currency?

-

2.

What are the 5 ‘signposts’ for outdoor environmental education to be recognised as a profession?

-

3.

You are preparing for a job interview. How would you answer the question, ‘Should outdoor environmental education become an accredited profession?’

-

4.

Critically evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of requiring outdoor environmental education graduates to demonstrate professional currency to employers.

-

5.

List five activities that an HE graduate can undertake to provide evidence of professional currency in outdoor environmental education.

Recommended Further Reading

-

Gass, M. A., Gillis, H. L., & Russell, K. C. (2020). Adventure therapy competencies. In M. A. Gass, H. L. Gillis, & K. C. Russell (Eds.), Adventure therapy: Theory, research and practice (2nd ed., pp. 216–238). London/New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

-

Higgs, J., & Trede, F. (Eds.). (2016). Professional practice discourse Marginalia. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

-

Potter, T., & Dyment, J. (2016). Is outdoor education a discipline? Insights, gaps and future directions. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 16(2), 146–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2015.1121767

-

Thomas, G., Grenon, H., Morse, M., Allen-Craig, S., Mangelsdorf, A., & Polley, S. (2019). Threshold concepts for Australian university programs: Findings from a Delphi research study. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 22(3), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-019-00039-1

References

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership Limited (AITSL). (2018). Australian professional standards for teachers. Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership Limited. https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards. Accessed 10 May 2020.

Brookes, A. (2004). Astride a long-dead horse: Mainstream outdoor education theory and the central curriculum problem. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 8(3), 23–33.

Clayton, B., Harding, R., Toze, M., & Harris, M. (2011). Upskilling VET practitioners: Technical currency or professional obsolescence? National Centre for Vocational Education and Research (NCEVR). http://avetra.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/24.00.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2020.

Ford, P. (1986). Outdoor education: Definition and philosophy. Eric Digest Outdoor Education: Eric Clearinghouse. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED267941.pdf. Accessed 11 Dec 2019.

Ingvarson, L., Meiers, M., & Beavis, A. (2005). Factors affecting the impact of professional development programs on teachers’ knowledge, practice, student outcomes & efficacy. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13(10). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v13n10.2005

Institute for Outdoor Learning. (2020). 7 steps to continuing professional development. The outdoor professional. Occupational standards. Institute for Outdoor Learning. https://www.outdoor-learning.org. Accessed 30Apr 2020.

Kiewa, J. (2003). Have we made it happen? Reflections on the summit of 2001. Keynote speech. In Polley, S. (Ed.), Relevance: Making it happen. Proceedings of the 13th national outdoor education conference. Adelaide, April 14–16, 2003, pp. 11–18. Australian Outdoor Education Council. https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/28171662/2003nationaloeconference_proceedings.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2020.

Larkin, I. (2003). A code of ethics for outdoor educators. In Polley, S. (Ed.), Relevance: Making it happen. Proceedings of the 13th national outdoor education conference. Adelaide, April 14–16, 2003, pp. 115–120. Australian Outdoor Education Council. https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/28171662/2003nationaloeconference_proceedings.pdf. Accessed 5 May 2020.

Mann, K. (2003). Rethinking professional pathways for the outdoor industry/profession. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 7(1), 4–9.

Marsden, D., Hanlon, C., & Burridge, P. (2012). The knowledge, skill and practical experience required of outdoor leaders in Victoria. In D. Burke & B. Stewart (Eds.), Sport, culture and society: Connections, techniques and viewpoints (pp. 77–94). Maribyrnong Press.

Martin, P. (2003). The heart of outdoor education’s contribution to the 21st century. In Polley, S. (Ed.), Relevance: Making it happen. Proceedings of the 13th national outdoor education conference. Adelaide, April 14–16, 2003, pp. 205–228. Australian Outdoor Education Council. https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/28171662/2003nationaloeconference_proceedings.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2020.

Meredith, M. (2010). 2010 National outdoor education conference report. Outdoor News, 27(5), 6–7. http://www.oeasa.on.net/pdf/journal/on27-5.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2020.

Munge, B. (2009). From the outside looking in. A study of Australian employers’ perceptions of graduates from outdoor education degree programs. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education, 13(1), 30–38.

Murray, C., & Lawry, J. (2011). Maintenance of professional currency: Perceptions of occupational therapists. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58, 261–269.

Occupational Therapy Board Australia (OTBA). (2019). Registration standard: Continuing professional development. Occupational Therapy Board of Australia. https://www.occupationaltherapyboard.gov.au/Registration-Standards/Continuing-professional-development.aspx. Accessed 10 May 2020.

Polley, S., & Thomas, G. (2017). What are the capabilities of graduates who study outdoor education in Australian universities? The case for a threshold concepts framework. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 20(1), 55–63.

Potter, T., & Dyment, J. (2016). Is outdoor education a discipline? Insights, gaps and future directions. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 16(2), 146–159.

Professional Standards Councils (PSC). (2020). The 40 elements of professionalism. Professional Standards Councils.https://www.psc.gov.au/what-is-a-profession/academic-view#. Accessed 14 May 2020.

Thomas, G., Grenon, H., Morse, M., Allen-Craig, S., Mangelsdorf, A., & Polley, S. (2019). Threshold concepts for Australian university programs: Findings from a Delphi research study. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 22(3), 169–186.

Wilderness Education Association (WEA). (2020). Accreditation. https://www.weainfo.org/accreditation. Accessed 5 May 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Polley, S. (2021). Professionalism, Professionalisation and Professional Currency in Outdoor Environmental Education. In: Thomas, G., Dyment, J., Prince, H. (eds) Outdoor Environmental Education in Higher Education. International Explorations in Outdoor and Environmental Education, vol 9. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75980-3_30

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75980-3_30

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-75979-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-75980-3

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)