Abstract

Relationships are important to the developmental success of young children. Specifically, strong relationships between parents and their young children provide a foundation for lifelong healthy growth and development. Furthermore, partnerships between parents and other adults, including educators, who are actively involved in children’s lives also support positive developmental trajectories. Distinct from programming focused on parent involvement, partnership-based interventions encourage active connection and collaboration between parents and educators. Getting Ready is one such early childhood parent engagement intervention that promotes children’s learning and development by enhancing relationships and strengthening partnerships among families and early childhood educators.

This chapter describes the evidence-based Getting Ready intervention, including the eight Getting Ready strategies and collaborative process used by educators in their interactions with families. Research evidence highlighting the intervention’s effectiveness on child, parent, and teacher outcomes is included. Though evidence of effectiveness has been established, there remains much to be learned about mechanisms contributing to intervention effects, issues that influence its uptake, challenges associated with implementation and cost, and a host of other important variables that have potential to impact how it is received and maintained. The chapter concludes with a research agenda to guide future investigations of the Getting Ready intervention and support scale-up and use in new settings and programs.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Family engagement

- Home-school partnerships

- Parent

- Educator relationships

- Getting Ready

- Ecological intervention

- Collaborative partnerships

- Early childhood intervention

2.1 Introduction to the Getting Ready Approach

From the beginning of life, children are inherently relationship seeking. Relationships early in a child’s life create a system of supports that facilitates healthy growth and development. Of all relationships, perhaps the one most important is the relationship a child has with a parent. Parents provide nurturance, security, and opportunities for stimulation. In ideal circumstances, parents help their children explore their environments and make sense of their world. They are their children’s first social agents, interacting in responsive and reciprocal ways and guiding their children as they learn to interact with others. Parents who are warm and sensitive, support their children’s emerging autonomy, and participate actively in their children’s learning – i.e., engaged parents – provide the context for an optimal early developmental trajectory. Thus, the focus of many family interventions in early childhood contexts is to promote parental engagement with their child to enhance learning and development.

Relationships with parents are not the only relationships that are important in young children’s lives. As children grow and develop, the responsibility for their learning becomes dispersed among a network of adults within and outside of the family system. Relationships among caregivers who are part of children’s broadened (i.e., cross-system) support network become important.

Family-school partnership approaches emphasize the bidirectional relationship between families and schools and enrich children’s outcomes through coordinated, cross-system supports (Downer & Myers, 2010; Lines et al., 2011). Distinct from parental involvement practices that emphasize parents’ parallel efforts to augment what educators do to promote learning, collaborative partnership practices focus on building positive working relationships between families and educators to promote children’s social, emotional, behavioral, and academic development.

Getting Ready is a parent engagement intervention that promotes children’s learning and development by enhancing relationships and strengthening partnerships among families and early childhood educators (ECEs). Foundationally, it is based on two research-based interventions in the field of early childhood and education: triadic (McCollum & Yates, 1994) and conjoint (i.e., parent-educator; Sheridan & Kratochwill, 2008) consultation. Its goals are to promote young children’s development by (a) engaging parents in meaningful ways; (b) enhancing relationships between parents and children, and between parents and ECEs; (c) building parents’ competencies at supporting children’s learning; and (d) strengthening collaborative partnerships between parents and ECEs. These goals are achieved through interactions between parents and educators that are characterized by reciprocity, trust, and shared responsibility for children’s learning and healthy development.

Getting Ready Strategies

Getting Ready supports ECEs in the flexible and responsive use of a series of eight strategies when interacting with parents. These strategies are used to support parents’ engagement; that is, they are intended to enhance parents’ relationships with their child and strengthen their role as partners. When used flexibly and effectively by ECEs, the strategies provide opportunities to support positive parent–child interactions, bolster parents’ confidence regarding their parenting practices, gently guide parents in methods for scaffolding their child’s learning, and ensure parents have input on how their child’s learning can best be encouraged at home and in other settings.

Table 2.1 outlines and defines each of the strategies. The Getting Ready strategies work in unison to support parents and children; they are not intended to be practiced in a rigid sequence or order. Collectively, the strategies are used to both strengthen relationships (e.g., communicate openly and clearly, encourage parent-child interaction, affirm parents’ competencies, make mutual decisions) and build parents’ competencies (e.g., focus parent’s attention, use observations and data, share information and resources, model and suggest new practices).

Implementation Contexts

Because the Getting Ready strategies are used in fluid and responsive ways, they can be integrated effectively into any situation wherein parents and educators have the opportunity to communicate about children’s learning and development. The myriad contexts within which Getting Ready strategies are used include those that are structured and unstructured, as depicted in Fig. 2.1.

Structured contexts, or settings, are those where formal educational discussions and planning occurs between an educator and parent. In early childhood programs, structured settings include 60-minute home visits and parent–ECE conferences conducted with at least one parent, the ECE, and the child. As part of the Getting Ready approach, ECEs complete 12 structured contacts over two study years (i.e., six contacts annually). Contacts that take place in structured contexts are extended, regular opportunities for parents and educators to partner about a child’s learning.

One of the ways that a partnership between parents and educators can be maximized is through a collaborative planning process wherein the unique perspectives and expertise of both parties come together. Many important topics can be explored through a structured, collaborative process, including individual child strengths, goals shared by parents and ECEs, plans for helping the child realize her/his potential across home and school, and assessments about whether a child is meeting important goals. Specific situations where a collaborative planning process provides important structure in a constructive and mutually respectful way are home visits, parent–educator conferences, and Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) or Individualized Education Plan (IEP) meetings.

During structured contacts, a collaborative process provides a method for planning, supporting, and monitoring mutually determined developmental goals and targets. The collaborative planning process creates a formal opportunity for parents and educators to assume mutual responsibility for a child’s learning and development. The process is strength-based, capitalizing not only on a child’s strengths but also the strengths of ECEs and parents given their unique sources of expertise when it comes to supporting a child. Essentially, this structured partnership creates a safety net for children, ensuring that parents and educators are working together in consistent and intentional ways.

The collaborative planning process used in structured Getting Ready parent–educator contacts is depicted in Fig. 2.2. It is comprised of six steps that are practiced in a cyclical, goal-directed manner: (1) establish/reestablish a partnership with parents; (2) discuss child strengths and concerns; (3) select or review/revise goals; (4) develop a partnership plan; (5) engage parent and child in an interactive activity; and (6) reflect and specify action steps. As an ECE guides parents through the collaborative planning process, she/he uses the Getting Ready strategies (e.g., open communication, affirm parents’ strengths, make mutual decisions; see Table 2.1) in an intentional way to enhance relationships, build parent competencies, and strengthen partnerships with parents.

In addition to structured settings such as home visits and conferences, Getting Ready strategies are relevant and useful in any parent–educator interaction. Unstructured situations include all brief encounters between educators and parents during daily and weekly routines, as well as during school- or agency-sponsored family activities. Unstructured contexts occur naturally and “on the spot” when interacting with parents. Examples include conversations when a mother drops her child off at a childcare center or picks her up at the end of the day, during family fun nights, via phone calls, and in email or text messages. Some unstructured opportunities occur incidentally, without extensive preplanning (such as at child drop off); others can be organized with advance thought (such as a daily information-sharing sheet written to update a parent about her child’s day). Although brief and unstructured, these exchanges with parents are practiced by educators with intention. They represent potentially powerful opportunities to affirm a parent, focus his attention, check in on progress at home, and engage in a host of other practices that build relationships and enhance a parent’s competency.

Getting Ready Training and Support

In Getting Ready, ECEs participate in a one-day training institute where they receive information about the Getting Ready strategies and collaborative planning. Exposure to the goals, strategies, and implementation contexts (e.g., structured and unstructured interactions with parents) occurs via formal presentations, video exemplars, practice-friendly materials, and discussion. Following the training institute, ECEs are supported in their delivery of the Getting Ready intervention with families through 90-minute individualized and small group coaching delivered bimonthly by an early childhood coach. Coaching sessions follow a format that includes initiation, observation/action, joint planning, reflection, and evaluation (Rush & Shelden, 2011). The agenda for each coaching session focuses primarily on a specific Getting Ready strategy, its use with individual families and ECEs, and steps in the collaborative planning process. Coaches use reflective questions, identify ECE strengths, and develop action plans with ECEs to support upcoming structured and unstructured interactions with parents. Getting Ready coaches have extensive experience in early childhood settings, and a minimum of a bachelor’s degree in Early Childhood Education or related field.

2.2 Getting Ready’s Research Evidence

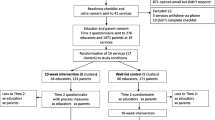

Research evidence gathered across multiple randomized trials indicates the effectiveness of the Getting Ready approach for parents and children. These randomized trials follow educators, parents, and children across the entirety of their two-year preschool experience, allowing for rigorous evaluation of Getting Ready’s impact over time through multiple methods of assessment. In each trial, data have been collected via direct assessment of child school readiness competencies, parent and ECE report, and observational assessment of parent and child behaviors. To control for time spent with an ECE, our studies ensured that treatment and comparison group participants received the same number of structured contacts with families over their 2 years in preschool. Further, an observational tool was developed for fidelity evaluation of Getting Ready strategy use by ECEs during structured contacts with families. Following a lengthy training protocol to establish reliability to a gold standard, observers used partial interval coding to record use of Getting Ready strategies during 1-minute intervals across home visits. Trained observers also recorded interactions and evaluated parent engagement and ECE effectiveness during these structured contacts. Fidelity data were collected for both treatment and comparison group allowing for stringent evaluation of ECE use of Getting Ready strategies during structured contacts and to uncover practices of both the Getting Ready and control group participants (Knoche et al., 2010).

In a randomized controlled trial of 220 typically developing preschool children attending publicly funded preschool programs, results indicated positive contributions to children’s school readiness as well as parental engagement. As compared to children in the comparison condition, children involved in the Getting Ready approach experienced significant, positive gains in school readiness skills including social-emotional, language, and early literacy readiness. Educators reported significant gains in children’s attachment with adults and initiative, as well as a reduction in their levels of anxiety and withdrawal (effect size range = 0.56–0.75; Sheridan et al., 2010). Similarly, relative to comparison group children, those whose ECEs were part of the Getting Ready intervention group showed significant decreases in overactive behaviors (e.g., disruptive, dysregulated play behaviors) when observed interacting with their parents (effect size = −0.71; Sheridan et al., 2014). Teachers’ reports of children’s language use, reading, and writing skills also were enhanced after participating in Getting Ready (effect sizes = 1.11, 1.25, and 0.93, respectively; Sheridan et al., 2011).

Parents also experienced gains as a result of their participation in Getting Ready. Parents in the programs who experienced the Getting Ready intervention were observed to be significantly more warm and sensitive in interactions with their children and supportive of their children’s autonomy and offered more developmentally appropriate guidance, directives, and learning supports as compared to parents in the “business as usual” control group (effect sizes = 0.67–1.23; Knoche et al., 2012). They also reported greater levels of self-efficacy, including enhanced beliefs and confidence in their abilities to interact with their children (Knoche et al., 2020).

It is worthwhile to explore for whom Getting Ready is most effective by investigating child- and family-level moderators that may be associated with differential treatment effects. Exploring moderation helps to illuminate intervention strengths and limitations, thereby guiding future refinements and applications as the intervention transitions outside of research to real-world contexts. Moderation analyses revealed that Getting Ready was most effective at improving the expressive communication, language use, early reading, and writing skills of children with a developmental concern at the beginning of preschool. That is, children in Getting Ready demonstrated the largest gain in language and literacy outcomes when a developmental concern was evident upon entry into preschool (Sheridan et al., 2011). Children’s home language was another significant moderator of language and literacy outcomes. The effect of Getting Ready on children’s language use was greatest for children whose parents indicated their child’s language as other than English upon entry into preschool (Sheridan et al., 2011).

Getting Ready requires the active participation of families; therefore, family characteristics may also moderate intervention effects. Indeed, family characteristics (e.g., education, household composition, health) interacted with the Getting Ready intervention in important ways to impact children’s development (Sheridan et al., 2011). When parents had less than a high school education or GED, there was significantly less improvement in children’s expressive language as a function of Getting Ready. In addition, when parents reported more health concerns, children made fewer language gains in the Getting Ready intervention. Parent mental health also moderated intervention effects, such that parents who reported more depressive symptomatology but were involved in Getting Ready had children who showed greater improvements on their positive affect and verbal behaviors (Sheridan et al., 2014). Household composition was another moderating factor; the number of adults in the home moderated the effects of Getting Ready on children’s language outcomes. It is possible that greater improvements in children’s language were noted when more adults were residing in the home; alternatively, it is possible that children in single parent households responded less favorably. More research is needed to disentangle the influence of number of adults in either amplifying or lessening Getting Ready’s effects.

To further advance our understanding of the effects of the Getting Ready intervention, we assessed effectiveness in a second randomized trial, focusing on a group of children exclusively at educational risk, defined by measured delays in performance. This study included 267 preschool-aged children and their parents. Results were consistent with findings generated from the first study, including positive intervention effects on children’s relationships and language skills. Specifically, when parents and educators were engaged in Getting Ready, children showed enhanced social skills across the two-year preschool period and improved relationships with their educators, relative to the comparison group, based on educator report (effect sizes = 0.24–0.33; Sheridan et al., 2019). Additionally, educators involved in Getting Ready reported significant gains in their relationships with parents relative to their peers who did not participate (effect size = 0.36).

2.3 Implications of Getting Ready Findings for Future Intervention Design and Research

Despite the increasing empirical support for the efficacy of the Getting Ready approach, important research questions remain. In this section, we explore directions in need of further empirical investigation. A current agenda for Getting Ready research, presented below, includes identifying (a) core intervention components, (b) mechanisms of change, (c) long-term effects, (d) the role of provider variables and support, (e) cost, (f) adaptations and scalability, (g) contextual influences, and (h) the role of language.

Core Intervention Components

Many Getting Ready studies have explored its effects as a multidimensional intervention comprised of strategies delivered by ECEs, across structured and unstructured situations, with the support of an early childhood coach. Much more research is necessary to pinpoint components of the intervention that contribute significantly to observed effects. Core components, or “kernels” of the Getting Ready intervention, are those elements that have a reliable effect on one or more desired outcomes and that are necessary to observe the effect (Embry & Biglan, 2008). This type of empirical approach to operationalizing the intervention will aid our understanding of the essential features of Getting Ready, and their role in promoting positive effects.

Mechanisms of Change

Getting Ready research has focused primarily on its effect on children’s developmental outcomes, with much less attention to variables that are responsible for or influence its efficacy. By definition, Getting Ready is comprised of collaborative strategies led by an ECE during all interactions with parents, with the primary goal of supporting children’s positive growth. To date, no research has been conducted exploring the pathways (i.e., mediators) by which the primary goal is achieved.

Extant discussions of Getting Ready have presumed select inputs (i.e., implementing the eight GR strategies in structured and unstructured situations, engaging in a collaborative planning process) are responsible for its positive outcomes. As an indirect model, however, it is implied that Getting Ready operates through other mechanisms (e.g., ECE-parent partnership, parent-child relationship) to effect change in children’s learning and behavior. Because parents are the direct recipients of the intervention, we assume these inputs (strategy use, collaborative planning) are associated with proximal change in parents’ behaviors (i.e., increased parent engagement, defined in terms of enhanced parent-child interactions) and subsequent child outcomes. There are several mechanisms, however, that may facilitate or enhance the effects of the inputs on parent behavior change and are worthy of investigation. Collaboration and partnership between parents and ECE professionals may result in uptake of parents’ skills to the extent that the partnership yields action steps for practices at home, engenders trust, and builds parental self-efficacy and confidence. In turn, parent engagement is expected to directly modify child outcomes. Parent-child interactions that are nurturing and stimulating, continuity in practices between home and classroom/center, and enhanced relationships between parents and ECEs are all possible mediators of Getting Ready on child outcomes. It is also possible that some of these same variables (e.g., collaboration, partnership) amplify or moderate the effects of the Getting Ready inputs on parent engagement practices. Further studies that verify mediating and moderating variables that influence proximal and distal outcomes of Getting Ready are needed.

Long-Term Effects

Longitudinal follow-up data are needed to determine if Getting Ready’s effects on parents’ practices to support their child’s learning, and partnerships formed between parents and educators who work with their child in later grades, will have downstream effects on child skills in future years. That is, it is possible that parents who received Getting Ready in preschool will bring their enhanced skills and expectations with them to relationships with new educators as their children progress through the elementary years. Likewise, educators they encounter over time vary greatly in their perspectives and practices vis-à-vis parent engagement. Given that the Getting Ready approach effectively improves relationships between parents and their child’s ECE during preschool, it is important to understand how future interactions unfold.

Role of Provider Variables and Support

Importantly, the Getting Ready intervention has been used by ECEs of varying educational backgrounds and levels of experience. In our studies to date, the educational backgrounds of educators have ranged from those with high school diplomas through advanced post-baccalaureate degrees. The early childhood knowledge of educators varies with some ECEs having teaching certificates, early childhood endorsements, or other specialized training. Furthermore, educators have varying years of experience working with children and families as well as differing levels of tenure within agencies or programs. To date, we have not explored how these educator variables contribute to educators’ abilities to deliver the Getting Ready intervention and the subsequent effectiveness of Getting Ready strategies with families. A question for future research is whether any adaptations in the Getting Ready training model are needed to accommodate ECEs based on prior education, experience, or skillsets.

Professional development via a coaching model appears to be essential to educators’ uptake of the Getting Ready approach and is ideally suited to handle the unique background characteristics and experiences of ECEs. We currently provide coaching across one full year of implementation. In our coaching model, a Getting Ready coach and early childhood educator co-implement meetings with parents; the coach provides modeling, encourages reflective practice, helps educators set implementation goals, and scaffolds new skill development. In the second year, that level of support is weaned and educators assume responsibility for implementing Getting Ready with parents. This method of coaching has been useful in supporting educators in their use of Getting Ready; however, we need to understand if there are other, more efficient ways of preparing ECEs in implementing Getting Ready at high levels of fidelity. We also need to identify how specific coaching supports interact with educator characteristics. For example, whether educators with differing levels of education require a tailored approach to coaching (e.g., varying by characteristics such as frequency of contact, planning time with a coach) to implement Getting Ready is not currently known. It is possible that ECEs will vary in the amount of support needed (i.e., some may not require a full year of implementation support) to achieve fidelity in the Getting Ready model. These types of analyses will allow us to tailor professional development offerings and increase efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Cost

Once established, Getting Ready is conceptualized as a “way of doing business” and not a curriculum with prescribed lessons. Likewise, it is time insensitive, meaning that it is not constrained with a starting and ending point. Thus, once the Getting Ready skills are successfully embedded within the ECEs everyday practices, there are no incremental costs to maintaining the intervention (or very minimal costs that might be associated with periodic professional development booster sessions). That is, as a professional approach that defines the manner in which ECEs interact with children and parents in the naturalistic setting of classrooms and home visits, there are no “extra” costs in daily operations. Likewise, the intent is that ECEs and parents can use materials that are already available in the classroom or home setting; thus, there is no need to purchase additional curricular materials or teaching or learning tools.

Hence, the major costs of the Getting Ready intervention involve the initial training and supporting ECEs through individualized or small group coaching. Research is needed to quantify the costs associated with training and supporting ECEs as they learn to engage parents actively as partners and as they acquire skills associated with the Getting Ready strategies, contexts, and collaborative planning elements. In addition, research is needed to determine whether the Getting Ready skills are sustained in the daily practice of trained ECEs or whether some level of ongoing supervision, monitoring, or periodic professional development support is needed to sustain high-fidelity implementation of the Getting Ready strategies.

Adaptations and Scalability

Ultimately, a goal for early childhood intervention researchers is to develop an evidence-based product that supports and improves developmental outcomes for young children. A related challenge is moving that product from a research context to an authentic practice environment. The process of translating an evidence-based approach to the real world is guided by an implementation science framework (Metz et al., 2015). Using this framework, we will approach scale-up of Getting Ready through stage-based implementation including exploration, installation, initial implementation, and, ultimately, full implementation. Data and feedback loops, including rapid-cycle problem solving, will be a priority implementation component as we move forward to provide assessment of need, infrastructure, and usability. To prepare Getting Ready for a move to scale, we must first understand modifications and adaptations that may produce strong treatment effects with greater efficiency, thus facilitating scalability. Specifically, we are interested in exploring the duration and intensity of the intervention and professional development, as well as user-friendly methods for measuring fidelity.

Getting Ready has been operationalized and evaluated as a two-year intervention. This requires implementation across 2 years of preschool or 2 years of infant/toddler programs. The duration was intentionally selected to align with the partnership focus of the intervention based on the recognition that relationships would need time to evolve. The professional development model as previously described includes 1 year (six visits) of co-facilitation between coach and educator with a reduction in support during the second year. While this duration and intensity have produced significant gains, there are limitations when considering a move to authentic early childhood programs. Given typical programmatic resources, the length and cost of a two-year coaching model with an exclusive focus on family engagement may be a barrier to wide dissemination. Additionally, many children are enrolled in pre-K settings for only 1 year before kindergarten, yet we want this model to be effective for all children and families and not just those enrolled for 2 years of programming. Thus, we may improve the scalability of the program if we can identify methods for increasing intervention intensity over a shorter period of time (i.e., one academic year or less). Furthermore, our current approach for measuring fidelity has been designed through a research lens. As previously discussed, a more efficient and less complex tool for monitoring fidelity needs to be developed and tested. With these adaptations to duration, intensity, and measurement, our partnership intervention could move more readily to real-world early childhood settings.

Contextual Influences

Most of the research on Getting Ready has taken place in the Midwest, namely, one state (Nebraska) that is comprised of two urban areas and many remote rural communities. Our research has not sufficiently explored the effect of geographic locale on the uptake and effects of Getting Ready. For example, services in rural communities may be situated in unique settings relative to those offered in urban contexts. Differences between settings in personnel (education, training, experience, availability), connections with other early childhood professionals, opportunities for professional development, financial resources, and external community supports for families may influence how the Getting Ready or other family engagement interventions function. Though we have not explored the impact of geographic or similar contextual variations on the implementation and efficacy of Getting Ready intentionally, it has been effectively implemented in communities of varying population size and demographics and in programs experiencing a range of internal and external resources. We have reason to believe it could generalize given our experience in various communities to date; however, because our research has been relatively confined to the Midwest, we simply do not know how geographic factors interact with the Getting Ready approach and its effects.

Over several years, we have worked in various program contexts, such as Early Head Start, Head Start, Part C programming, and other publicly funded programs. Variability in policies, services, personnel, support staff, agency resources, and other contextual factors that may influence uptake and sustainability need to be considered in future research. Different practice settings provide very different delivery mechanisms and opportunities for parents and ECEs to interact. For example, we recognize that our specification of six meaningful contacts taking place in home visits or conferences may not be plausible in all settings. Contrarily, in some situations and within some early childhood agencies, services are delivered entirely via a home-based approach with few opportunities for unstructured, incidental interactions between parents and ECEs. The intent is for Getting Ready implementation to become integrated seamlessly into existing service structures; thus, we need to explore carefully interactions between structural features of Getting Ready and contextual variations within which it is implemented to determine the feasibility and impact of varying implementation formats.

Role of Language

Little is known about practice implications and outcomes for children and families for whom English is not their first language. Whereas our prior evaluation of the Getting Ready intervention demonstrated greater effects on children’s expressive language skills when children did not speak English at preschool entry, there is still much to be learned about how this intervention works with non-English-speaking families. There may be added factors to consider when building collaborative partnerships with non-English-speaking families. The degree to which there is a match between parent and ECE in cultural expectations and spoken language may impact child and family outcomes of the intervention (Good et al., 2010).

A related area for future research involves the exploration of the role of interpreters when working with families for whom English is not their first language. To date the Getting Ready approach has been conducted with both English- and Spanish-speaking families. With English-speaking coaches and educators, the intervention has relied on the use of interpreters during structured contacts with Spanish-speaking families. While we have seen positive effects on outcomes for all families receiving the Getting Ready intervention, the role of the interpreter in intervention services delivered to non-English-speaking families remains underexplored. Beyond simply offering word-for-word translation, interpreters serve as cultural and linguistic brokers during structured contacts as they attempt to relay the meaning behind the words expressed by both teachers and parents (Cheatham, 2011; Davitti, 2013). This suggests that interpreter level characteristics, such as years of experience in early childhood, knowledge of the family, and familiarity with the Getting Ready intervention, may impact the interpreter’s ability to both accurately relay information and assist in the promotion of a collaborative partnership between educator and parent. As interpreters working with the Getting Ready intervention have ranged from family members or family friends to project or agency staff, the impact of these characteristics warrants investigation. Further, observational assessments have shown that factors such as positioning of the interpreter, eye contact between conversational partners, and interpreter’s use of gesturing impact parent engagement during parent-teacher interactions (Davitti & Pasquandrea, 2017). Future research should assess the impact of these factors on parent engagement in the intervention.

Additionally, the linguistic needs of early childhood programs continue to grow more diverse as programs have increasing numbers of English language learners who are part of many diverse language groups. Future work should focus on how to scale up Getting Ready to meet these varied needs, as the intervention to date has exclusively focused on working with English- and Spanish-speaking families. A first step may be examining the feasibility and impact of providing all written materials translated into the parent’s first language for families with a first language other than English or Spanish (Ma et al., 2014).

2.4 Conclusions

The Getting Ready intervention has been developed and tested in several randomized controlled trials over the past two decades. We have found routinely that it is efficacious for producing important outcomes for children and parents and that with training and intentional professional support, ECEs can implement the intervention in ways that improve quality of engagement relative to comparison participants. Much is now known about child and family characteristics that moderate certain effects. However, there is a plethora of research questions still to be addressed, including those associated with mediation (how the Getting Ready operates to produce certain effects), cost, fidelity and uptake, scalability, role of providers’ personal and professional characteristics, contexts, and influence of family language, to name a few. These and related issues provide a robust research agenda moving forward.

References

Cheatham, G. A. (2011). Language interpretation, parent participation, and young children with disabilities. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31, 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121410377120.

Davitti, E. (2013). Dialogue interpreting as intercultural mediation: Interpreters’ use of upgrading moves in parent–teacher meetings. Interpreting, 15, 168–199. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.15.2.02dav.

Davitti, E., & Pasquandrea, S. (2017). Embodied participation: What multimodal analysis can tell us about interpreter-mediated encounters in pedagogical settings. Journal of Pragmatics, 107, 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2016.04.008.

Downer, J. T., & Myers, S. S. (2010). Application of a developmental/ecological model to family–school partnerships. In S. L. Christenson & A. L. Reschly (Eds.), Handbook of school–family partnerships (pp. 3–29). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Embry, D. D., & Biglan, A. (2008). Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 11, 75–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-008-0036-x.

Good, M., Masewicz, S., & Vogel, L. (2010). Latino English language learners: Bridging achievement and culture gaps between schools and families. Journal of Latinos and Education, 9, 321–339.

Knoche, L. L., Sheridan, S. M., Edwards, C. P., & Osborn, A. Q. (2010). Implementation of a relationship-based school readiness intervention: A multidimensional approach to fidelity measurement for early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.05.003.

Knoche, L. L., Edwards, C. P., Sheridan, S. M., Kupzyk, K. A., Marvin, C. A., Cline, K. D., & Clarke, B. L. (2012). Getting ready: Results of a randomized trial of a relationship-focused intervention on parent engagement in rural early head start. Infant Mental Health Journal, 33, 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21320.

Knoche, L. L., Sheridan, S.M., Boise, C.E., Prokasky, A.A., Scruggs, S.L. & Hechtner-Galvin, T.S. (2020). Creating connections between infant/toddler educators and families: Effects of the Getting Ready 0-3 approach. In K. Dwyer (Chair), Targeting parents and teachers to support infant and toddler development: Initial findings from the Early Head Start Parent-Teacher Intervention Consortium. Paper symposium presented at the 2020 National Research Conference on Early Childhood, Washington, DC, United States.

Lines, C., Miller, G. E., & Arthur-Stanley, A. (2011). The power of family–school partnering (FSP): A practical guide for school mental health professionals and educators. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Ma, X., Shen, J., & Krenn, H. Y. (2014). The relationship between parental involvement and adequate yearly progress among urban, suburban, and rural schools. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25, 629–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/092433453.2013.862281.

McCollum, J. A., & Yates, T. J. (1994). Technical assistance for meeting early intervention personnel standards: Statewide processes based on peer review. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 14, 295–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/027112149401400303.

Metz, A., Naoom, S. F., Halle, T., & Bartley, L. (2015). An integrated stage-based framework for implementation of early childhood programs and systems (Research Brief OPRE 2015–48). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation.

Rush, D. D., & Shelden, M. L. (2011). The early childhood coaching handbook. Baltimore: Brookes.

Sheridan, S. M., & Kratochwill, T. R. (2008). Conjoint behavioral consultation: Promoting family–school connections and interventions. New York: Springer.

Sheridan, S. M., Knoche, L. L., Edwards, C. P., Bovaird, J. A., & Kupzyk, K. A. (2010). Parent engagement and school readiness: Effects of the getting ready intervention on preschool children’s social–emotional competencies. Early Education and Development, 21, 125–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280902783517.

Sheridan, S. M., Knoche, L. L., Kupzyk, K. A., Edwards, C. P., & Marvin, C. A. (2011). A randomized trial examining the effects of parent engagement on early language and literacy: The getting ready intervention. Journal of School Psychology, 49, 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2011.03.001.

Sheridan, S. M., Knoche, L. L., Edwards, C. P., Kupzyk, K. A., Clarke, B. L., & Kim, E. M. (2014). Efficacy of the getting ready intervention and the role of parental depression. Early Education and Development, 25, 746–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2014.862146.

Sheridan, S. M., Knoche, L. L., Boise, C. E., Moen, A. L., Lester, H., Edwards, C. P., Meisinger, R. E., & Cheng, K. (2019). Supporting preschool children with developmental concerns: Effects of the getting ready intervention on school-based social competencies and relationships. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 48, 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.03.008.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sheridan, S.M., Knoche, L.L., Boise, C. (2022). Getting Ready: A Relationship-Based Approach to Parent Engagement in Early Childhood Education Settings. In: Bierman, K.L., Sheridan, S.M. (eds) Family-School Partnerships During the Early School Years. Research on Family-School Partnerships. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74617-9_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74617-9_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-74616-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-74617-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)