Abstract

Christian Wolff discusses the so-called three systems of mind–body interaction (which are actually five systems including materialist and idealist monism) at quite some length in the Psychologia rationalis, without arriving at a conclusion, however, that he himself considers satisfactory. He does support pre-established harmony eventually, but only as the lesser evil. In a similar vein, he officially endorses Leibnizian monadology but adds the caveat that it applies only to minds, thus in fact rejecting the monistic panpsychism that is characteristic at least of Leibniz’s mature metaphysics. The aim of this chapter is to disentangle some of the complexities of Wolff’s view of the mind–body problem and thus shed some light on what his view of it and of related metaphysical issues actually amounts to.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

This chapter deals with a few core metaphysical aspects of Wolff’s psychology, specifically with his understanding of monadology and the doctrine of pre-established harmony.Footnote 1 I will try to specify to what extent Wolff repudiates Leibniz’s understanding of monads as the basic elements the world is composed of, and what the alternative he puts forward consists in (Sects. 7.2 and 7.3). I will also reconstruct Wolff’s motivation behind this repudiation that I believe is based on his opposition to materialism and his supposition that Leibniz’s doctrine of monads might not be able to avoid it (Sect. 7.4). My topic is thus not restricted to rational psychology but touches on general ontology and cosmology as well. For, although Wolff restricts pre-established harmony to the interaction between human mind and body, his repudiation of Leibniz’s version of it is based on broader metaphysical considerations. Leibniz’s monadology is a general ontological doctrine, and what Wolff finds dubious about it pertains to his alternative general ontology (which he develops mostly within his cosmology). I will thus look more closely into Wolff’s theory of simple substances.

In Wolff’s own interpretation, Leibniz is straightforward as to how simple things act: Leibniz argues, according to Wolff, that each simple thing represents the entire world from its own perspective. Wolff considers this to be a consistent explanation of how each simple thing differs from all other simple things, and how each simple thing is related to the entire world. However, he remains hesitant: “But I still have reservations about adopting this” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.598, p. 368), and he becomes more outspoken in the Anmerckungen , where he remarks that “he cannot endorse what Herr von Leibniz has taught about the monadibus ” (Wolff, 1724, p. 462). So while Wolff appreciates Leibniz’s monadology and deems it a consistent philosophical theory, he ultimately remains unconvinced. Nonetheless, he states that it is not only internally consistent, but also compatible with his own doctrine: it is “not contrary to what we have established with regard to the elements of the world” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.599, p. 369). But what are the reasons for these “reservations”? And since Wolff does not reject monadology in general, how does he modify and appropriate it? The concept of “element” is Wolff’s replacement for that of monad, as I will discuss in more detail below. The question thus is to what extent Leibniz’s doctrine of monads goes together with Wolff’s doctrine of elements, and where their differences lie. Wolff’s own take on Leibniz’s monadology has been discussed in the literature on various occasions. Brandon Look, for instance, argues that Wolff advances a “non-Leibnizian theory of simple substances” by rejecting their representational nature (Look, 2013, p. 199). According to Look, this explains why Wolff is a weak advocate of the doctrine of pre-established harmony: Wolff claims that it is a likely hypothesis, but remains mostly agnostic about further details (p. 201). In a similar fashion, Eric Watkins argues that Wolff is agnostic about whether all simple substances must have a representative power (see Watkins, 2006, pp. 275–90, in particular p. 281).Footnote 2 So according to this view, Wolff is mainly less straightforward than Leibniz and rather remains agnostic about some of its more ambitious aspects.

In this chapter, I want to defend a slightly different though not entirely incompatible view on this score: Wolff’s “doctrine of elements” is a minimal theory of simple things and their operation. This doctrine of elements is minimal, compared to Leibniz’s monadology, in that it does not necessarily include that simple things as such have mental attributes. However, it does not exclude mental features either. According to the minimal theory, all simple things have a certain set of attributes, but only some of them have mental attributes in addition.Footnote 3

My suggestion is thus more in line with the (albeit brief) accounts of Christian Leduc and Gualtiero Lorini (Leduc, 2018; Lorini, 2016). Leduc also argues that Wolff with the “elements” introduces a basic concept that is quite different from Leibnizian monads but not incompatible with them, and not just a less ambitious or more cautious version of Leibniz’s conception.Footnote 4 I thus call Wolff’s theory of simple substances a minimal theory because it is partly, but not entirely agnostic about their essence. Hence, although we do not know much about them, we do know something and can establish this as a minimal metaphysical theory.

2 Wolff’s Minimal Theory of Elements

The passages where Wolff notes his hesitations about Leibniz’s monadology that I have discussed so far remain rather vague as to what exactly bothered Wolff. There is one passage in a recently edited letter, though, that Leduc (2018) mentions and that is quite informative in this regard:

I have known the abbot Mr. Conti for many years, and I have received letters from him for almost 30 years, or even longer, dating back to when Herr von Leibnitz’ [sic!] monads still used to be a puzzle; although even now only a few know them and have an appropriate notion of his system which only begins where mine ends. The confusion, however, is due to Herr Bülffinger who first came up with the concept of a Philosophia Leibnitio-Wolfiana. And thus one could still say that the Leibnizian monads on which his actual system is built are a puzzle that has not been fully resolved, and that I do not like to resolve although I could, because I do not need it in my endeavours and therefore I leave it at that, in its value and its disvalue. (Middell & Neumann, 2019, vol. 2, pp. 287–292).

This letter provides some interesting information. First, Wolff obviously takes issue with being too closely aligned to Leibniz. Second, Leibniz’s monadology is a puzzle that Wolff has no intention to solve (though he claims that he could), because it is unnecessary for his purposes. So neither his doctrine of elements nor the purported pre-established harmony between human mind and body require a full understanding and acceptance of Leibniz’s doctrine. This suggests that Wolff intends his own theory to be more independent and different from Leibniz’s one than one might expect.

According to Wolff, simple things must exist because the world is a composite thing, and composite things must ultimately consist of simple things. There must be simple things ultimately because otherwise, the parts of the composed things would have to consist in yet smaller parts, according to Wolff. If that were so, however, “we could give no reason where the composed parts ultimately come from”, in a similar way as “we could not comprehend how a composite number originates if it did not contain any units in it” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.76, p. 36). The principle of sufficient reason demands that such a reason exists. Thus, there must be simple things, according to Wolff, because only simple things can serve as the sufficient reason of composed things whose parts they are. Watkins (2006, p. 276f.) has provided a concise formal reconstruction of this argument, the essence of which is, in abbreviation:

-

1.

If there were no simples, everything would be composite.

-

2.

If everything were composite, all parts of composites would be further divisible (in infinitum).

-

3.

If all parts were divisible into parts, there would be no ultimate reason for the existence of the parts.

The key to Wolff’s argument seems to consist in the third premise: infinitely divisible parts lack a proper reason of their existence. But why is that, i.e. what exactly would qualify as a sufficient reason of parts? Watkins (2006) discusses a few clues from Wolff’s Ontologia that are helpful here although they ultimately rest on a premise that is itself problematic (Wolff, 1736/1977a, §§.686, 533, 789–791). In brief, in the Ontologia Wolff argues that composition as a mere relation is fundamentally accidental, i.e. the essence of a composite being must be something else and thus requires a substance, according to Wolff. If composition is only accidental, only the entities that are combined can be substances, and thus composition ultimately depends on the things that are combined.

This line of reasoning illustrates why Wolff thought that combination requires non-composite ultimate parts, although it seems problematic in itself. One might object that physically indivisible atoms could serve as a foundation as well, though Wolff would reply that physical atoms are still divisible geometrically. Another potential objection is that Wolff still does not explain how exactly unextended parts can be combined in such a way as to yield extended composites, i.e. that the most pressing issue is not solved in the way suggested. But these issues are not important for the purposes of this chapter.

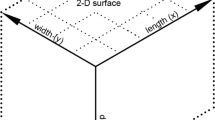

Having established the necessity of simple things, Wolff calls those simple things the world is composed of “elements” in the cosmology section of Deutsche Metaphysik (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.582). These elements exist by themselves (compare Wolff, 1751/1983, §.127) and can only cease to exist by annihilation (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.102), i.e. they are substances. Wolff infers from the simplicity of simple substances that (1) they have no size and no parts, (2) they are not composed of other things, (3) they do not occupy space, and (4) they do not have inner physical motion (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.73).Footnote 5 These are the attributes of extended, composite things; thus, simple things are heterogeneous with them; i.e., “we cannot attribute anything we perceive in them [composite things] to simple ones” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.82, pp. 40). As the elements are simple substances, the same applies to them (compare Wolff, 1751/1983, §§.583ff.), and as simple things and thus the elements are indivisible, they can only be limited by degrees (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.125); i.e., they only have different intensive magnitudes. Things that are both indivisible and limited by degrees have a power, according to Wolff:

-

1.

Indivisible things contain a manifold because otherwise there would be no ground for the different degrees that are the basis of their limitations.

-

2.

Because this manifold is grounded in a simple thing but is also mutable and thus not absolutely necessary, it can become real only through the action of the simple thing.

-

3.

This action arises from a continuous effort, and thus a simple thing must have a power.

Wolff seems to argue here that due to their simplicity, simple things cannot be acted upon “from outside” like material objects that can be pushed or otherwise mechanically impacted by other material objects. But simple things such as the human soul or the elements of material objects do undergo modifications. If there is no intelligible way of there being an external influence on simple things, though they do change, this change must have an internal source. Thus, simple things can only have an internal source of modifications, while at the same time, they must have a source of modifications since they are not absolutely necessary and thus mutable (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.127).

In §.597 of Deutsche Metaphysik , Wolff discusses these internal sources in more detail: the inner state of a simple thing is nothing but the kind of “limitation” of the grounds of its existence, and its modifications are changes in its limitations―in the same way as, for instance, concepts are limitations of the soul (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.121). The modifications of a simple substance are the changes of its limitations, and at the same time, they are nothing but the alterations of the degree of its powers, according to Wolff (compare Wolff, 1751/1983, §.115). Simple things continuously act in this way, and thus, their actions must have an effect not only on all other simple things, but also on all composite things in the entire world since they are all connected. But Wolff deliberately leaves it open at this stage what exactly the effects of the actions of the simple things are, thus he is agnostic in this quite specific regard.

In the Anmerckungen , Wolff states that there is a general harmony between the states of simple things, in the sense that their states correspond to each other (Wolff, 1724, p. 337). But it remains an open question what exactly this harmony consists in. Wolff thus acknowledges that he has not determined yet what the inner state of elements and their powers consists in. So, again, Wolff’s ontology is clear about some things: that there are simple elements composite things are composed of and that they have a power, but agnostic about others, e.g. what that power is, or whether it is one and the same for all elements. The latter point―that there may be different kinds of elements with different kinds of powers―is an idea Wolff discusses in another passage in the Anmerckungen , in fact in one of the few passages where he reveals a little more of his metaphysics of elements (Wolff, 1724, §.215). Wolff here again protests against the “allegation” that he identified Leibnizian monads with the basic elements of the world. While he acknowledges that the elements must have a power that causes the modifications of their states, he finds fault with the Leibnizian idea that all elements have one and the same kind of power. He here ponders whether the elements of corporeal things may have a specific power (distinct from the power of mind-like things) “wherefrom the power of the bodies that reveals itself in addition to their modification in motion can be deduced in an intelligible way” (Wolff, 1724, §.215, p. 335). So, the specific power of the elements of corporeal things would be one to which modifications of material objects can be reduced, and it would allow one to explain the modifications of material objects other than motion.

Moreover, Wolff maintains that he also has a proof of the mental nature of many other simple things that represent the world in a less perfect way than the human soul. Wolff hence does allow for simple things that only have dark, i.e. unconscious representations, and are thus in a persistent sleep-like state (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.900). This description matches the one Leibniz has given for the lowest kind of monads, “simple” monads. But even though Wolff believes in the existence of permanently “sleeping” simple things, he explicitly rejects Leibniz’s view here that all elements of the world are of this kind: “I have mentioned above already … that I will leave it undecided for the time being whether the elements are the kind of things that represent the world in an obscure way, that is without being conscious of it” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.900, p. 560). So according to Wolff, there may be simple things that only have unconscious mental states, but there may also be simple things that have no mental states at all.

Wolff concludes his discussion of simple things or elements on the cosmological level by announcing that he will prove in his rational psychology (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.742) that the human soul belongs to the class of simple things. Significantly, this proof consists in an anti-materialist argument; i.e., Wolff seeks to prove the simplicity of the soul by way of proving that matter cannot think and that the soul has a power to represent the world (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.753).Footnote 6 Wolff thus claims that he has a proof for the mental nature of some of the simple substances, namely human souls, whereas for Leibniz, each simple thing represents the entire world (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.598). Hence, it seems obvious that Wolff mainly takes issue with Leibniz’s view that all basic elements in the world have mental features, a view that has often been called Leibniz’s “panpsychism” or “idealism”. I will use the former term here because Wolff sets aside idealism for George Berkeley (1685–1753) alone (Wolff, 1740/1994, §.36).Footnote 7

For Wolff, Leibnizian monads are merely a possibility: “such things are possible, like the Leibnizian unities of nature ” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.599), because monads have all the features required for simple substances (according to Wolff, 1751/1983, §.597). These common features are that (1) the inner state of a simple thing is its kind of limitation; (2) its modifications are the changes of its limitations; and (3) its modifications are nothing but the modifications of the degrees of its powers. This much holds true of all simple things per se, regardless of their further metaphysical nature. So according to Wolff, we know quite a few things about the basic elements of the world, significantly more than a thoroughly agnostic theory would maintain.

Leibniz’s monadology thus turns out to be a more specific version of Wolff’s minimal theory of elements: according to the minimal theory, the inner state of all elements refers to all other things in the world, and Leibniz explains this relation more specifically as one of representation, the representation of the entire world in every simple thing according to its location: “and Herr von Leibniz had explained this [relation] in such a way that in each simple thing the entire world is represented according to the point where it is” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.600, p. 370). The minimal theory of elements, on the contrary, merely states that the simple elements are related to all other things while leaving it undetermined or more abstract in what that relation consists. Remarkably, though, Wolff does not only cite Leibniz’s monadology as a kind of theory that shares a common ground with his theory of elements, but also that of Henry More (1614–1687) (Wolff, 1737/1977b, §.182), albeit in a rather superficial way.Footnote 8 More (1671, pp. 75–87) does speak of monads, mostly “monades physicae”, but merely as a synonym for atoms.Footnote 9

Wolff could conceive of Leibniz’s doctrine of pre-established harmony as one potential application of his own theory of simple things: it consists in the representations of the elements matching with the states of the world, whereas Wolff allows for the possibility that this relation may be explained differently, i.e. not as one of representation. One might call this indeterminacy “agnostic”, but it is a rather local agnosticism that does not extend any further. Wolff also readily acknowledges that some of the elements of the world, namely souls, do relate to other things by way of representation; he only questions whether all elements of the world operate in this way. This explains why there is not a lot of disagreement between Wolff and Leibniz when it comes to rational psychology as such, as I will discuss in what follows.

3 Wolff on Simple Souls

I will address two points here: First, briefly what Wolff positively has to say about simple souls; and second, how he conceives of pre-established harmony in relation to mind–body interaction.

Wolff concludes that because material bodies and matter in general cannot think, the entity underlying thought must be simple. Since all simple things are substances and thus exist per se, also the soul is a substance (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.743). Because every simple thing has a power, it can be the source of its own modifications (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.127). Thus, the status of the soul as a substance comes with a power that is the source of its modifications (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.744), and it can only have one single power since the soul has no real parts.

In the Psychologia rationalis Wolff states: “The elements of material things are not spirits” (Wolff, 1740/1994, §.644, p. 588). It is important to note that in Leibniz’s terminology, a spirit is a specific kind of monad; i.e., not all monads are spirits in spite of their mental features.Footnote 10 Only monads that have apperception, beyond perception and appetition, qualify as spirits, for Leibniz. Wolff explicitly acknowledges this and states: “Leibniz admittedly attributed perception and appetition to his monads, from which he thought that they are the elements of material things, but without apperception” (Wolff, 1740/1994, §.644n, p. 589). Thus, Wolff does not reject the Leibnizian concept of monad in this very passage but rather acknowledges that Leibniz does not hold the problematic view that brute material things have fully developed mental states—notwithstanding Wolff’s general reservation about Leibnizian pre-established harmony.

So, what is Wolff’s view of pre-established harmony when applied to the mind–body relation alone? Notably, experience plays a crucial role in Wolff’s argument. He maintains that it is a basic fact of experience that there is often a “harmony” between the thoughts (or mental states) of our soul and bodily events. That is, we often experience accurate mental representations of the actual state of our body, for instance when a part of our body is modified in a way that results in an injury. Our representation of our bodily states is correct more often than not.Footnote 11 That is what he has in mind when he speaks of the experiential fact of harmony. But experience alone just reveals that there is some harmony, i.e. that mental states match with bodily ones, but it does not include any hint as to the metaphysical grounds of it, according to Wolff.

On the basis of this experiential advantage for pre-established harmony, Wolff criticizes the two other “systems” of mind–body interaction, i.e. physical influx and occasionalism. Against physical influx, or natürlicher Einfluß, Wolff objects that it is a naive common sense doctrine whose followers believe that it is based on experience while it is really not. He sees important theoretical arguments against physical influx, primarily the familiar one that minds acting on bodies would increase the motive force in the world, which however should remain constant (Wolff, 1740/1994, §.762). According to occasionalism (in Wolff’s reconstruction under the name of “Cartesianism”), God causes thoughts in the mind and motions in the body, and the soul is only the occasional cause of certain motions in the body such as voluntary ones. Wolff objects that the actions of body and soul are not sufficiently distinct from those of God, according to this system, and since they are not primarily grounded in the nature of body and soul, they are miracles.Footnote 12

Wolff insists that it is not enough to maintain that God has set up the harmony between mental and bodily states, which would make pre-established harmony collapse into occasionalism. To distinguish pre-established harmony from occasionalism, it is crucial for Wolff that the chains of modifications both in bodies and in minds follow their immutable orders respectively, so that it suffices that they have been put into harmony only once, i.e. at the very creation. After this, they have to be able to proceed based on their own laws paralleling each other, without further divine intervention. But these demands are fulfilled by Leibnizian pre-established harmony, and Wolff thus states that “in the system of pre-established harmony the interaction [commercium] between soul and body … is explained in an intelligible way” (Wolff, 1740/1994, §.620, p. 552) and that as a consequence, the “system of pre-established harmony … is to be preferred in rational psychology over the other systems explaining the interaction between soul and body” (Wolff, 1740/1994, §.639, p. 581). It thus turns out that Wolff can easily accommodate Leibnizian pre-established harmony to his own views of mind–body interaction and thus prefer it within rational psychology, and why he can do so.

4 Against “Materialisterey”: Why Did Wolff Find Fault with Leibnizian Panpsychism?

After having discussed the internal mechanics of Wolff’s theory of simple elements and the arguments he makes explicit against Leibnizian panpsychism, it remains to be seen what the philosophical motivation of his rejection of the latter could be. Watkins has pointed out that Wolff asked Leibniz for a proof of the mental nature of the basic elements but never received an answer. Thus, Wolff’s motivation could be that while he grants that some simple things, namely souls, have the power to represent the world, “he notes that it has not yet been proved that all simples must have such a power” (Watkins, 2006, p. 282). Leibnizian panpsychism is thus problematic plainly because there is no appropriate proof available. In what follows, I would like to discuss another reason why Wolff would consider Leibniz’s proposal problematic (not in contrast but in addition to Watkins).

It is first striking that Wolff’s rejection of materialism plays a central role within the very arguments of Deutsche Metaphysik and Psychologia rationalis. In the rational psychology part of Deutsche Metaphysik , the rejection of materialism figures at the beginning right after the introductory definitions of consciousness and thought (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.727–737). Similarly, the claim that material bodies cannot think is the first actual claim Wolff makes in Psychologia rationalis: “The body cannot think” (Wolff, 1740/1994, §.44, p. 29). Moreover, Wolff explicitly seeks to establish the simplicity of the soul by way of rejecting materialism, i.e. in an indirect way and distinctly not by a positive argument like, for instance Descartes does. As Wolff puts it:

Because a body can, according to its essence and nature, neither think (§.738.739) nor can a power to think be communicated to it or to matter (§.741); the soul cannot be anything corporeal nor consist of matter (§.192). And since it becomes evident from the proofs of the reasons discussed that thoughts cannot inhere in a composite thing; the soul must be a simple thing. (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.742, p. 463)

And since the soul is a simple substance, Wolff concludes: “Materialism is a false hypothesis” (Wolff, 1740/1994, §.50, p. 33). There are other indications that Wolff did see materialism as the foremost opponent of his theory, for instance when he complains in the Anmerckungen that “materialism [die Materialisterey] gets out of control these days—unfortunately!—, and thereby people drawn to salaciousness are pulled away from religion and call the immortality of the soul into question” (Wolff, 1724, p. 413).

The main point here is that Wolff’s hesitation about panpsychism and his rejection of materialism are in fact two sides of the same coin. Even though there is no doubt that Leibniz opposed materialism, one could still see materialist potential in the claim that all ontologically basic things in the world, monads, have mental states because it includes that also the elements material objects are composed of have them. It is thus possible that Wolff thought that Leibniz’s doctrine is not strong enough against materialism, or that it even unintentionally provides a foundation materialists could make use of. First, since monads are the only basic elements of the world, all elements of the world have mental features, including the monads material objects are composed of. But this comes dangerously close to claiming that matter can think in an at least rudimentary way, which Wolff avoids by claiming that the elements of material objects do not have this feature. Second, monads are inherently active, since all monads have appetitions. As matter too is based on monads, materialists could exploit this feature for their purposes, since many of them (with the potential exception of Hobbes) consider matter to be fundamentally active.Footnote 13 This is not to say that Wolff or anyone else constructs Leibniz as a secret materialist, but rather that Wolff saw that materialists could disingenuously use Leibnizian panpsychism as a source of inspiration.Footnote 14

There are also more general reasons for Wolff to put particular emphasis on the rejection of materialism during the first decades of the eighteenth century. As he himself notes in the passage quoted above, die Materialisterey was on the rise. Although early modern materialism is often associated with Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) and Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), John Locke’s (1632–1704) proposal that God could have endowed matter with the capacity of thought was the most important origin of materialist theorizing. John Yolton, for instance, has thus argued that the

story of the thinking matter controversy in eighteenth-century Britain is largely the story of reactions to Locke’s suggestion. While Hobbes and Spinoza are routinely cited as the arch materialists, it is to Locke’s suggestion that most of the reactions were directed. (Yolton, 1983, p. xi).

It is thus apt that Wolff pays particular attention to Locke-inspired materialism, as I will discuss in what follows.

The turmoil caused by “die Materialisterey” occurred not only in Britain, however, but also in Wolff’s immediate academic context. The best-known case is that of the clandestine pamphlet Zweyer guten Freunde vertrauter Brieff-Wechsel vom Wesen der Seele (The intimate correspondence of two good friends on the nature of soul) that was written by Urban Gottfried Bucher (1679–?), a medical student at Wittenberg and Halle between 1704 and 1707, and published anonymously in 1713, probably without Bucher’s knowledge.Footnote 15 Wolff had been a university professor at Halle since 1706. Bucher’s text was widely known and attacked immediately. It was mentioned by the theologian Johann Franz Budde (1667–1729) as early as 5 February 1713, a lecture was devoted to it in the summer semester of 1713 at Jena (by Johann Jacob Syrbius, 1674–1738), and it was criticized in Valentin Ernst Löscher’s (1673–1749) periodical Unschuldige Nachrichten von alten und neuen theologischen Sachen. These were only the beginnings of a then widely known controversy.Footnote 16 Bucher’s pamphlet is straightforwardly materialistic in claiming, for instance, that there is no human soul (not even a material one, Bucher, 1713, p. 17) and that instead all mental content derives from sensation, which in turn derives from the sense organs and the nerves (Bucher, 1713, pp. 19–21).

Hence, there was ample reason for Wolff to address materialism in particular, which would explain why its discussion figures so prominently in Deutsche Metaphysik and Psychologia rationalis. Turning towards Wolff’s actual arguments against materialism, it is striking that he presents three different ones: the first against materialism in general and two further ones against specific forms of materialism, both in Deutsche Metaphysik and in Psychologia rationalis . The first, general argument is presented in a rather confusing way in §.738 of Deutsche Metaphysik and in almost identical fashion in §.44 of Psychologia rationalis. Essentially, Wolff seeks to make the following points here:

-

1.

According to Wolff, all modifications of a material body occur through motion and are based on the size, shape and position of the parts of the body. If a body could think, its thoughts would have to be modifications based on the position of some of its parts, and the modifications would have to be caused by a determinate motion.

-

2.

If the body were to become conscious of these modification and thus think―thoughts are, by Wolff’s definition, modifications of the soul it is conscious of (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.194)―the different states of the body would have to be compared and their differences noticed.

-

3.

This cannot be accomplished by the motion of parts, “because they cannot do anything other than represent something composite by means of their size, figure and position” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.738, p. 461).

So Wolff seems to allow for the possibility that material objects represent something, but he denies that they can become aware of it, however without providing a more detailed argument than the one outlined. The argument is reminiscent to some extent of what has come to be called the “Achilles argument” according to which the unitary character of thought requires a unitary substratum, but it would be too speculative to treat it as an actual instance of this argument.Footnote 17 Another possibility is that Wolff simply wants to make the point that consciousness and physical motion are too heterogeneous to render one of them the cause of the other, similar to Leibniz’s mill example in the Monadology (Leibniz, 1714/1885, p. 609).

Wolff’s arguments against specific forms of materialism are in fact more interesting. First, Wolff addresses the widespread idea that human thought is based on a specific kind of matter that differs from ordinary, tangible matter. He thus acknowledges: “I know well that those who attribute thoughts to the body fancy that thoughts consist in the motion of a subtle matter in the brain” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.739, p. 461). Against this proposal, Wolff indicates that his refutation of materialism is not restricted to “gross” matter and insists that also subtle matter can only yield representations of something composite: “For we cannot make it any further than that a representation of a composite is best obtained in this way; but consciousness, which is still required for thought (§.194), is missing as it is earlier [i.e. in the first argument]” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.739, p. 461). Historically, a materialist recourse to subtle matter was often combined with the view that there is a soul distinct from the body that is composed of subtle matter.Footnote 18 This seems to be Wolff’s target in §.47 of the Psychologia rationalis where he makes a separate point that the “soul cannot be material or a body”, although he has previously established that bodies cannot think (Wolff, 1740/1994, §.44).

Wolff’s second, more specific argument is intended to reject the possibility that God could have endowed a material body or matter in general with the capacity to think, i.e. Locke’s proposal. He thus acknowledges that “I know well that some believe that God could communicate the power of thinking to a body, or, as they argue even more awkwardly, to matter” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.741, p. 462). What Wolff has in mind here is Locke’s proposal that the latter conceived rather as a theoretical possibility than actually advocating it: Locke argues that our cognitive means do not allow us to exclude the possibility that God has endowed matter with the capacity of thought by way of “superaddition”. He argues that it “being, in respect of our Notions, not much more remote from our Comprehension to conceive, that GOD can, if he pleases, superadd to Matter a Faculty of Thinking, than that he should superadd it to another Substance, with a Faculty of Thinking” (Locke, 1690/1975, p. 541).Footnote 19 Although this proposal was often seen as a contribution to materialist theory, if not a concealed endorsement, Locke himself does not intend to establish materialism but rather argues that our cognitive means are insufficient to decide between the options of dualism and materialism, in part because we do not even understand the idea of thinking. His argument is thus both directed against dogmatic materialists and dualists

who … finding not Cogitation within the natural Powers of Matter, examined over and over again, by the utmost Intention of Mind, have the confidence to conclude, that Omnipotency it self, cannot give Perception and Thought to a Substance, which has the Modification of Solidity. (Locke, 1690/1975, p. 542).

In detail, Wolff argues against Locke:

-

1.

By claiming that God should endow matter with the capacity of thought, (crypto-) materialists of this kind acknowledge that material things as such cannot think, since they need an external power to enable them to do so. Similarly, Wolff states against this theory: “The faculty of thinking cannot be communicated to the body or to matter, which they do not have by themselves” (Wolff, 1740/1994, §.46, p. 31).

-

2.

If the (crypto-) materialists of this camp were right, God would have to “occasion that from the essence of a body something follows that cannot follow from it and thus either change the essence of that thing, or to at the same time communicate the essence of another thing that has the capacity of thought to it” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.741, p. 463).

-

3.

But it is known both that the essence of a thing is invariant and that it cannot be communicated to another thing.

-

4.

Therefore, arguing that God could communicate the power of thought to matter is tantamount to arguing that God could turn one thing into another one in such a way that it would have the essential features of both things at the same time.

In sum, Wolff argues that it is impossible for God to attribute faculties to material bodies that they do not already have by their own nature, which is exactly what Lockean superaddition would amount to. Providing a material body with the capacity of thought would be tantamount to either changing the essence of that body or to bestow the essence of another thing on it at the same time. But essences are immutable, according to Wolff, and also one thing cannot have two different essences concurrently. Accordingly, Wolff argues that maintaining that God communicates the power of thought to matter implies “demanding that GOD should turn iron into gold at the same time, so that is would be iron and gold at the same time” (Wolff, 1751/1983, §.741, p. 463). Apparently, essence means something like substance concept here, in the sense of a concept that provides the most fundamental answer to the question: what is that thing? There can be only one answer to this question for a given thing, although it may be controversial what this answer is. For instance, one could argue that human beings are most fundamentally organisms, or one could argue that they are persons most fundamentally. Either way, they cannot be both most fundamentally.Footnote 20

5 Conclusion

Although Wolff deems Leibnizian panpsychist monadology a consistent philosophical theory, he refuses to adopt it. But instead of merely remaining agnostic about whether the most basic things in the world have mental features, he sets up a more abstract theory of “elements”. Whereas monads have a power to represent the world, elements have an indeterminate power, or different kinds of them could have different kinds of powers, including but not restricted to representative ones. Thus, all monads (including basic ones that just have unconscious representations) are elements, in Wolff’s ontology, but not all elements are monads. Monads or “mental elements” are just ordinary elements with some additional, mental features, whereas human souls, or more precisely: spirits, are elements with additional, more advanced features, and thus Wolff is content to hold both monadology and pre-established harmony when taken as an explanation of the human mind and its interaction with the body. To conceive of all basic elements of the world as having mental features, on the other hand, would open a door to materialism, which makes it plausible why Wolff was at great pains to avoid the panpsychist aspects of Leibnizian monadology.

Notes

- 1.

A preliminary version of this chapter was presented at the conference “Christian Wolffs Deutsche Metaphysik/Christan Wolff’s German Metaphysics” at Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. I would like to thank the participants of this conference for their helpful comments, as well as Eric Watkins for his detailed and thorough comments on a later draft.

- 2.

- 3.

Watkins would agree thus far, I take it that the main point of disagreement here is whether this is primarily an agnostic thesis about the ultimate constituents of the world, or an actual, positive claim about them.

- 4.

Leduc (2018) argues that Wolff introduces the concept of element to designate the first constituents of bodies in the first place (i.e. without mental attributes at all) and mentions Leibniz just as one example of such a theory among others.

- 5.

Wolff (1751/1983, §.583) makes it clear that the internal power of simple things is not to be confused with an inner motion, i.e. a kind of physical motion, as that would require real parts, which a simple thing obviously does not have.

- 6.

I will analyze this peculiar argument in Sect. 7.3 in more detail.

- 7.

For an overview of the discussions of Leibniz’s “idealism” or “panpsychism”, see Smith (2011, pp. 101–105).

- 8.

I take this reference to More from Leduc (2018, p. 46).

- 9.

On this, see Reid (2012, pp. 44–51), in particular p. 51.

- 10.

Compare Leibniz’ Monadology (1714/1885, p. 609).

- 11.

Wolff discusses various empirical cases of harmony between mind and body in the section on empirical psychology in Deutsche Metaphysik (Wolff, 1751/1983, §§.527–539).

- 12.

This criticism of Malebranche is neither original (i.e. adopted from Leibniz) nor fair, because in Malebranche, God acts through natural laws and not by miraculous intervention (see Perler & Rudolph, 2000, pp. 229–234).

- 13.

On this aspect, compare Wunderlich (2016) and Wunderlich (forthcoming). On Leibniz as a potential resource for materialism see also Wolfe (2014, pp. 96–99, in particular p. 97f.) on Leibnizian influences on Diderot and Montpellier vitalism.

- 14.

A case in point would be John Toland (1670–1722) who appropriated and modified Leibnizian theorems into a partly Spinozistic, materialistic doctrine; compare, for instance, Leask (2012) and the literature quoted there.

- 15.

For a detailed reconstruction of the contents of this pamphlet and its publication history, see Mulsow (2002) and Mulsow (2018, vol. 2, pp. 11–96). Bucher apparently discussed the manuscript with his teacher Johann Baptist Roeschel (1652–1712). It was found in Roeschel’s estate and then later published by an unknown editor (see Mulsow, 2018, vol. 2, pp. 27, 37f).

- 16.

For details of the reception of Bucher’s pamphlet, see Mulsow (2018, vol. 2, pp. 73–77).

- 17.

Compare, for instance, Lennon and Stainton (2008).

- 18.

Compare Wolfe and van Esveld (2014).

- 19.

- 20.

For this use of substance concepts, see Olson (1997, pp. 27–31). Thanks to Eric Watkins for pointing me to this problem.

References

Blackwell, R. (1961). Christian Wolff’s doctrine of the soul. Journal of the History of Ideas, 22(3), 339–354.

Bucher, U. G. (1713). Zweyer Guten Freunde vertrauter Brief-Wechsel vom Wesen der Seelen. Peter von der Aa (forged publisher).

Corr, C. (1975). Christian Wolff and Leibniz. Journal of the History of Ideas, 36(2), 241–262.

École, J. (1986). Des différentes parties de la métaphysique selon Wolff. In W. Schneiders (Ed.), Christian Wolff 1679–1754 (pp. 121–128). Meiner.

Fabian, G. (1925). Beitrag zur Geschichte des Leib-Seele-Problems. Hermann Beyer und Söhne.

Jolley, N. (2015). Locke’s touchy subjects: Materialism and immortality. Oxford University Press.

Leask, I. (2012). Unholy force: Toland’s Leibnizian ‘consummation’ of Spinozism. British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 20(3), 499–537.

Leduc, C. (2018). Sources of Wolff’s philosophy: Scholastics/Leibniz. In R. Theis & A. Aichele (Eds.), Handbuch Christian Wolff (pp. 35–53). Springer.

Leibniz, G. W. (1885). Principia philosophiae, Seu Theses in gratiam Principis Eugenii &c. [Monadology]. In C. Gerhardt (Ed.), Die philosophischen Schriften von Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (Vol. 6, pp. 607–623). Weidmann. (Original work published 1714).

Lennon, T., & Stainton, R. (2008). The Achilles of rationalist psychology. Springer.

Locke, J. (1975). An essay concerning human understanding. Clarendon Press. (Original work published 1690).

Look, B. (2013). Simplicity of substance in Leibniz, Wolff and Baumgarten. Studia Leibnitiana, 45(2), 191–208.

Lorini, G. (2016). Receptions of Leibniz’s pre-established harmony. Wolff and Baumgarten. In M. Camposampiero, M. Geretto, & L. Perissinotto (Eds.), Theodicy and reason: Logic, metaphysics, and theology in Leibniz’s Essais de Théodicée (1710) (pp. 163–179). Edizioni Ca’ Foscari.

Middell, K., & Neumann, H.-P. (Eds.) (2019). Briefwechsel zwischen Christian Wolff und Ernst Christoph von Manteuffel. 1738–1748 (3 Vols.). Olms.

More, H. (1671). Enchiridion metaphysicum. Flesher.

Mulsow, M. (2002). Säkularisierung der Seelenlehre? Biblizismus und Materialismus in Urban Gottfried Buchers Brief-Wechsel vom Wesen der Seelen (1713). In L. Danneberg, S. Pott, J. Schönert, & F. Vollhardt (Eds.), Säkularisierung in den Wissenschaften seit der frühen Neuzeit (Vol. 2, pp. 145–173). De Gruyter.

Mulsow, M. (2018). Radikale Frühaufklärung in Deutschland 1680–1720 (2 Vols.). Wallstein.

Olson, E. T. (1997). The human animal. Personal identity without psychology. Oxford University Press.

Perler, D., & Rudolph, U. (2000). Occasionalismus. Theorien der Kausalität im arabisch-islamischen und im europäischen Denken. Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht.

Reid, J. (2012). The metaphysics of Henry More. Springer.

Smith, J. E. H. (2011). Divine machines. Leibniz and the sciences of life. Princeton University Press.

Stuart, M. (2013). Locke’s metaphysics. Oxford University Press.

Watkins, E. (2006). On the necessity and nature of simples: Leibniz, Wolff, Baumgarten, and the pre-critical Kant. Oxford Studies in Early Modern Philosophy, 3, 261–314.

Wolfe, C. (2014). Materialism. In A. Garrett (Ed.), The Routledge companion to 18th century philosophy (pp. 91–118). Routledge.

Wolfe, C., & van Esveld, M. (2014). The material soul: Strategies for naturalising the soul in an early modern Epicurean context. In D. Kambaskovic (Ed.), Conjunctions of mind, soul and body from Plato to the enlightenment (pp. 371–421). Springer.

Wolff, C. (1724). Der vernünfftigen Gedancken von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen überhaupt, anderer Theil, bestehend in ausführlichen Anmerkungen. Andreae.

Wolff, C. (1977a). Philosophia prima, sive Ontologia, methodo scientifica pertractata, qua omnis cognitiones humanae principia continentur. In J. École (Ed.), Christian Wolff: Gesammelte Werke (Prima philosophia sive Ontologia) (Vol. 3, Pt. II, 2nd ed.). Olms. (Original work published 1736).

Wolff, C. (1977b). Cosmologia generalis, methodo scientifica pertractata, qua ad solidam, inprimis die atque naturae, cognitionem via sternitur. In J. École (Ed.), Christian Wolff: Gesammelte Werke (Cosmologia generalis) (Vol. 4, Pt. II). Olms. (Original work published 1737).

Wolff, C. (1983). Vernünfftige Gedancken von Gott, der Welt und der Seele des Menschen, auch allen Dingen überhaupt. In C. Corr (Ed.), Christian Wolff: Gesammelte Werke (Deutsche Metaphysik) (Vol. 2, Pt. I, 11th ed.). Olms. (Original work published 1751).

Wolff, C. (1994). Psychologia rationalis, methodo scientifica pertractata, qua ea, quae de anima humana indubia experientiae fide innotescunt, per essentiam et naturam animae explicantur, et ad intimiorem naturae ejusque autoris cognitionem profutura proponuntur. In J. École (Ed.), Christian Wolff: Gesammelte Werke (Psychologia rationalis) (Vol. 6, Pt. II, 2nd ed.). Olms. (Original work published 1740).

Wunderlich, F. (2016). Varieties of early modern materialism. British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 24(5), 797–813.

Wunderlich, F. (forthcoming). Materialism. In D. Jalobeanu & C. Wolfe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of early modern philosophy and sciences. Springer.

Yolton, J. (1983). Thinking matter: Materialism in eighteenth-century Britain. University of Minnesota Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wunderlich, F. (2021). Wolff on Monadology and “Materialisterey”. In: Araujo, S.d.F., Pereira, T.C.R., Sturm, T. (eds) The Force of an Idea. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, vol 50. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74435-9_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74435-9_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-74434-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-74435-9

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)