Abstract

This study, informed by experiential learning and constructivist theories of learning, aims to examine online asynchronous and synchronous education in postsecondary contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic and offer recommendations for improving online teaching and learning. The COVID-19 pandemic has had educational impacts on student life, one being the physical closure of educational institutions. 26% of respondents in a recent study (Learning Disruptions, 2020) had some of their courses postponed or canceled. Almost all participants had some (17%) or all (75%) of their courses subsequently offered online. These numbers imply the popularity of online education as an alternative for face-to-face classes during the pandemic. Online learning seems a reasonable replacement for face-to-face instruction. However, students who lack appropriate tools – such as broadband Internet or no suitable home environment for remote learning – can find online learning challenging (Learning Disruptions, 2020). The studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in postsecondary contexts have tended to examine financial aspects (Measuring COVID-19’s Impact, 2020), medical education (Ferrel & Ryan, 2020), and students and staff’s health (Sahu, 2020). Little attention seems to be paid to the impact of COVID-19 on the quality of online teaching and learning. While the previous studies illuminate important issues, the need for investigating the quality of online education during the pandemic is felt. To bridge this gap, the study herein aims to examine online asynchronous and synchronous education in postsecondary contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic. The chapter reviews the literature on teaching and learning during the pandemic; then the authors’ teaching experiences in four General Studies and two Interior Design classes are presented. Conclusions are drawn and recommendations offered.

Teaching is the greatest act of optimism.

Colleen Wilcox

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Literature Review

Missing classes can negatively impact students’ skill growth during a pandemic (Burgess & Sievertsen, 2020). Also, while homeschooling can provide valuable learning opportunities for students, they are unlikely to replace formal education (Burgess & Sievertsen, 2020). The extent to which families can assist their children with education depends on their availability, resources, and noncognitive skills and subject matter knowledge (Oreopoulos et al., 2006). Furthermore, some exams have been administered online, which is a new experience for students and teachers and can “have larger measurement error than usual” (Burgess & Sievertsen, 2020, para. 12).

From a social justice perspective, teaching and learning during the COVID-19 outbreak can perpetuate inequalities between students from advantaged and disadvantaged backgrounds. The Canadian Radio and Telecommunications Commission (2019) discovered that only 69% of Canadians in the first income quintile, who earn less than 33,000 annually, had access to the Internet at home in 2017 compared to 94.5% in the fifth quintile, who earn more than $132,909 annually. Furthermore, only 63% of Canadians in the first income quintile have access to a home computer, compared to 95% of those in the fifth quintile. Therefore, students from first income quintile families are more likely to struggle with accessing the Internet and computer compared to those in the fifth quintile.

Similar challenges exist in Europe. 6.9% of children live in homes with no access to the Internet, and 5% of them have no appropriate place to complete assignments (Guio et al., 2018). Students living in these conditions struggle to continue their studies remotely, while those from a higher socioeconomic backgrounds shift to online education without encountering housing and Internet challenges (Van Lancker & Parolin, 2020). Many instructors have adapted their teaching, assessment, and classroom management techniques to facilitate remote learning for students. This chapter discusses two instructors’ experiences with remote teaching during the pandemic.

2 Theoretical Framework

This study has been informed by constructivist theories of learning. Constructivism implies that the learners are constructors of their own knowledge, which is created by interacting with their sociocultural environment (Vygotsky, 1978). Constructivism assumes that learners learn by connecting new information to old through the context where new information is acquired and learners’ attitudes and beliefs impact learning (Bada, 2015).

This study has also been informed by the experiential learning theory proposed by Kolb (1984). This model includes the following assumptions: (1) learning is a process, (2) learning is driven from experience, (3) learning requires the learner to resolve conflicts through dialogue, (4) learning carries a more holistic view, (5) learning requires the individual to interact with their environment, and (6) learning creates knowledge (Kolb, 1984; pp. 25–38).

The authors design teaching and learning activities according to constructivist and experiential learning theories. They review past lessons and provide the class with prerequisite information to assist them with learning new knowledge; then, they have the students complete task-based activities to discover new information. After that, the authors encourage the students to apply new knowledge to real-world situations. Although the previously classroom-based activities were modified to suit the new online environment, the principles of constructivist and experiential learning theory, including activating the students’ prior knowledge and assigning task-based activities and pair and group work, were followed in online classes.

3 The Study

3.1 Research Design and Methodology

This study presents two qualitative case studies, each detailed by one of the authors. According to Yin (2003), a case study design is used when (a) the focus of the study is to answer “how” and “why” questions, (b) the researcher cannot manipulate the participants’ behavior, (c) the researcher aims to cover contextual conditions because they believe they are relevant to the phenomenon under investigation, or (d) the boundaries are unclear between the phenomenon and context. This study aims to answer how and why the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted postsecondary education by describing and reflecting on the teaching and learning activities without manipulating students’ behaviors. The study investigates online education within the pandemic context because the shift to remote learning has occurred as a result of the pandemic, and the context and the phenomenon (teaching and learning) are inseparable.

3.2 Data Collection Procedure and Analysis

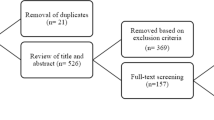

Data were collected by the authors taking descriptive and reflective field notes and analyzing the educational activities and classroom management techniques used during spring 2020 classes. The first author reflected on teaching four synchronous General Education courses in the undergraduate Bachelor of Business Administration program at Coastal University (a pseudonym). Synchronous courses refer to courses delivered via remote synchronous delivery with virtual classes in Zoom each week. The second author reflected on teaching two asynchronous Interior Design courses in the Bachelor of Art in Interior Design program at Global College (a pseudonym). The asynchronous courses refer to the weekly lessons delivered fully online with asynchronous resources, PowerPoint slides, lecture notes, discussion forums, activities, and assignments. The institutions’ name and course titles have been changed for confidentiality, and codes have been used to refer to them. The alphabetical letters, GE and ID, allude to the course titles. GE stands for General Education courses delivered via remote synchronous classes in Zoom each week, and ID refers to Interior Design (ID-Studio 1 and 2 classes) delivered completely asynchronously online. The authors wanted to compare and contrast the teaching experiences and findings related to synchronous and asynchronous online delivery.

While the researchers were collecting the field notes and educational documents, they would meet weekly to discuss their teaching experiences. This process began in April and ended in June 2020. The notes were color-coded based on major reoccurring themes, and the emerging themes were identified at our last meeting.

4 Results

4.1 Synchronous Classes

The synchronous GE studies lectures and classes were delivered via Zoom using PowerPoint slides. The students were assigned pair work, group work, and discussions in the breakout rooms during classes via Zoom video conferencing. Students also watched videos individually, answered discussion and comprehension questions, and read articles individually and collectively.

To assess student learning, the instructor asked students to answer comprehension and discussion questions in the breakout rooms while the instructor joined the rooms one at a time to monitor their participation. She also asked them comprehension, application, and critical thinking questions in the Zoom room and had them complete reflective papers and research projects at home.

The instructor created class policies, including assignment submission guidelines and classroom behavior and Zoom netiquette, and posted the documents on the class discussion forum. She explained the guidelines in the first session to clarify instructor expectations and course objectives. She also reminded the students frequently about netiquette, attendance, and assignment submission. Naghmeh would join the breakout rooms during discussions to monitor students’ participation.

4.2 Asynchronous Classes

Short lectures were delivered biweekly in the ID1-Studio class, and lecture slideshows were uploaded on the learning management system. The instructor also raised a discussion question on the online forum, the students answered it, and the instructor commented on their responses. A sample discussion question was “How would you define home? Refer to your readings for descriptions of home vs. house.”

Assignments were due weekly and biweekly in ID1-Studio. They consisted of a concept statement, client introduction, images, drawings, and schematic design. Comments were made by the instructor in writing and by drawings, for example, “There is no clear distinction between programmatic and design concept.” In later stages of design development in the course, a sample comment included: “Bulkhead is also extruded out which gives it a visible appearance. Is this intended? Explain.”

To record attendance and participation in ID1-Studio, the students were asked to complete an activity and submit the answer. This involved answering a question raised by the instructor about the discussed topic that week, and students were asked to comment on or summarize the concept. The instructor then commented on the posts. This activity counted as student attendance and participation.

The ID2 Software lectures were recorded, and their links were provided weekly for students. In the lectures, the instructor introduced Command and demonstrated its use and purpose. The video recording showed the computer screen accompanied by the instructor’s voice.

Assignments were due weekly or biweekly in ID2 Software. Submissions consisted of drafting, applying building information, modeling concepts and techniques. Assessment criteria were given for each assignment. They were detailed and related to the discussed commands during the week. Comments were given in writing, for example, “Visibility parameters were not set up correctly in the dynamic block.”

The ID2 Software students were asked to summarize the commands they had learned during the week and explain their application to record their attendance. Questions such as “Why would we use attributes in blocks?” were discussed and explained.

5 Opportunities

5.1 Synchronous Classes

While in large face-to-face classes, the instructor had a hard time remembering the students’ names, whereas in the online classes via Zoom, she could identify them by their names posted in the corner of their video screen from the beginning of the term. Calling the students by their first names added a personal touch to the instructor-student interaction.

Shifting to online education prevented the disruption of teaching during the pandemic. The curricula were delivered, the weekly topics were covered, and exams were administered as planned. Synchronous classes positively impacted the instructor-student relationship because they were able to virtually interact with each other, make eye contact, and clarify unclear ideas during class. Naghmeh’s students were asked to log into the Zoom classroom with their official names, and this facilitated identifying them. Also, the students were able to interact with each other in small groups or pairs in the breakout rooms, which provided a safe space for those who felt uncomfortable sharing their views in the main room and offered all the students an opportunity to participate in discussions.

5.2 Asynchronous Classes

ID1: In the design studio online, students were unaware of each other’s progress. As a result, they felt no peer pressure and could perform in a more relaxed learning experience.

ID2 Software students were able to watch the lectures at their convenience. They could also complete the weekly exercises at their own pace. This was a major advantage over face-to-face classes for design software. In the face-to-face classes, some students learned and performed the activities quickly, whereas other students were struggling to keep up with the instruction pace.

6 Challenges

6.1 Synchronous Classes

One challenge pertained to classroom management. In the first session, the instructor’s students in the four classes were given a set of policies to follow throughout the quarter. One of these policies pertained to attendance, according to which students needed to turn their video camera on during class and write their official full name as the display name. Some students in GE 1, 2, 3, and 4 logged in, entered the Zoom classroom, and turned off their cameras. The instructor constantly reminded them to turn on their cameras. Two students in GE4 asked whether they could keep the camera off because they were eating lunch. The instructor insisted they should turn the camera on; one student did, while the other one asked whether he could join the class in 5 minutes. The instructor accepted this to save class time and resume lecturing to avoid keeping the rest of the class waiting.

Students who lacked a private digital device sometimes used another person’s laptop, and the Zoom display name showed the laptop owner’s name rather than the student’s. The instructor would ask the student to revise their display name, and in some cases, the student was unable to do so. This made recording attendance challenging for the instructor.

Finding a quiet space for Zoom classes was sometimes also challenging for students who shared their place with roommates. Background noises and roommates’ presence would distract them and prevent them from fully engaging in discussions. These would also distract the instructor when the student’s microphone was on. In an instance in GE4, a student and their roommate were captured on camera chatting with each other, and the student was asked to move to a more private space. He mentioned that he lived in a crowded place, and his roommates continued chatting with him. He became distracted, and the instructor removed him from the class. This incident distracted the student, instructor, and probably other students and interrupted the lecture.

Having the students participate in the discussion in the breakout rooms was sometimes challenging. In some cases in GE2 and GE4, as sometimes the instructor found the students chatting and lying down instead of discussing the given topic.

6.2 Asynchronous Classes

ID1-Studio students were unaware of each other’s progress and did not spontaneously encounter each other; rather, they mainly interacted with the instructor. The instructor played a more prominent role as he was the only source for critique, compared to face-to-face classes. Also, the students needed to be comfortable with online learning tools. In a similar face-to-face design studio, students were expected to work in the college’s material library and select finishes. They would examine the finishes closely and use multiple senses such as vision and touch to select them. This was in contrast to the online experience where students were able to only use digital images. The previous classroom experience resulted in a more comprehensive learning experience.

ID2 Software class students contacted the instructor by email when they had a question. This delayed solving their problems, as opposed to face-to-face classes where the instructor was available for answering questions immediately in class.

7 Discussion

This chapter exemplifies synchronous General Education (GE) and asynchronous Interior Design (ID) courses that were previously offered face-to-face before the pandemic and were adapted to synchronous remote delivery and asynchronous online delivery, respectively, during the COVID-19 pandemic at two Canadian higher education institutions. In synchronous classes, the instructor would use Zoom for giving presentations, and in asynchronous classes, the instructor would record lectures or upload PPT files for students’ reference. In both methods, the instructors clarified the classroom policies for students to ensure a productive educational experience. Assessment in both methods was least affected by the shift to online teaching as instructors could comment on students’ assignments outside class time as both types of courses required that assignments be submitted via online assignment boxes.

Online teaching provided new opportunities in teaching. In synchronous classes via Zoom, students could be moved to breakout rooms for small group work. This enhanced the participation of those who felt uncomfortable participating in larger groups. In asynchronous classes online, there was no peer pressure, and in the asynchronous ID2 Software, the students could complete the tasks at their own pace.

Online teaching presented challenges alongside the opportunities. Lacking a private study space, interacting with roommates, and engaging in irrelevant activities during class time sometimes distracted the students and disrupted the synchronous lectures and discussions. Internet disruption affected both synchronous and asynchronous methods, while the former was affected more. In asynchronous classes, the students did not spontaneously interact with each other to exchange ideas and peer feedback, and the instructor’s role was more prominent compared to face-to-face classes: he delivered the lectures via video and PowerPoint, answered the students’ questions, and critiqued their works. Also, the multisensory experience of the design process was reduced to one dimension in online delivery, and the students had to adapt to working with online resources. In the face-to-face remote synchronous classes, the instructor was conveniently available for troubleshooting, whereas in asynchronous classes, the students needed to contact the instructor via email in case of problems. Despite the challenges, the instructors adapted to the situations caused by the pandemic, maintaining that “Teaching is the greatest act of optimism” (Colleen Wilcox).

Some of the opportunities and challenges described here demonstrate the advantages and disadvantages, as well as the social inequities in learning perpetuated by the pandemic. Other studies have revealed social inequalities caused by the pandemic in Europe (Van Lancker & Parolin, 2020). The study herein reveals that the pandemic has had similar consequences in Canada. Online teaching requires access to computers and the Internet, which for students from lower-income families is challenging. Students who had privacy while attending synchronous classes benefited more from the instruction, while those who shared their residence were often distracted and were unable to participate as much as others.

8 Recommendations

To teach synchronous and asynchronous classes, instructors need to post course/program policies which clarify instructor expectations, attendance requirements, assignment submission expectations, classroom management rules, and other class details. This document could be shared with the class in the first session. Clarifying these expectations can lessen students’ emotional burden, particularly during the potentially stressful time of a pandemic and other crises. "

Since delivering long lectures can tire the instructor and students, the instructor needs to give several short breaks during the synchronous class and also facilitate students completing individual, pair, and group activities. This can enhance autonomous and collaborative learning for the students.

Since students might lack high-speed Internet, personal digital devices, and a private study space to access synchronous lectures, instructors should provide alternative learning options such as posting the lecture files on the learning management system, as well as be available for one-on-one support during office hours.

In asynchronous classes, given students have different communication preferences, instructors should consider communicating with students through various ways such as chat, audio or video calls, and email.

Despite challenges, as professors we maintained our belief in “Teaching as an act of optimism.” We were able to adapt our teaching and courses to effectively transition and support our students in their General Studies remote synchronous courses via Zoom and asynchronous online Interior Design courses. Our main recommendation is to “teach with optimism.” COVID-19 has been a time of challenge but an opportunity for growth as well.

References

Bada, S. O. (2015). Constructivism learning Theory: A paradigm for teaching and learning. Journal of Research & Method in Education, 6(1), 66–70. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1c75/083a05630a663371136310a30060a2afe4b1.pdf

Burgess, S., & Sievertsen, H. H. (2020). Schools, skills, and learning: The impact of COVID-19 on education. Vox EU. https://voxeu.org/article/impact-covid-19-education

Canadian Radio and Telecommunications Commission. (2019). https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/publications/reports/policymonitoring/2019/cmr.htm

Ferrel, M. N., & Ryan, J. J. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Education. Cureus, 12(3), e7492. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7492

Guio, A. C., Gordon, D., Marlier, E., Najera, H., & Pomati, M. (2018). Towards an EU measure of child deprivation. Child Indicators Research, 11, 835–860.

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on post-secondary students. (2020). The Daily. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/200512/dq200512a-eng.htm

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experiences as a source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall.

Learning disruptions widespread among post-secondary students. (2020). Statcan COVID-19: Data to insights for a better Canada.https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00015-eng.htm

Measuring COVID-19’s impact on higher education. (2020). ICEF.https://monitor.icef.com/2020/04/measuring-covid-19s-impact-on-higher-education/

Oreopoulos, P., Page, M., & Stevens, A. (2006). Does human capital transfer from parent to child? The intergenerational effects of compulsory schooling. Journal of Labor Economics, 24(4), 729–760.

Sahu, P. (2020). Closure of Universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus, 12(4), e7541. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7541

Van Lancker, V., & Parolin, Z. (2020). COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making. The Lancet Public Health, 5(5), 235.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Sage.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Babaee, N., Ghandhari, S. (2021). The Quality of Teaching During the COVID-19 Era and Beyond. In: Fayed, I., Cummings, J. (eds) Teaching in the PostCOVID-19 Era. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74088-7_45

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-74088-7_45

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-74087-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-74088-7

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)