Abstract

This chapter introduces a conception of teachers’ ethos as a system of professional values, norms, and goals. Applying this perspective, we investigated preservice teachers’ endorsement of educational goals and their attribution of goals to school versus family in a four-wave panel study across the bachelor’s degree phase of initial teacher education. Specifically, we analyzed (1) how preservice teachers differentially endorsed social, intellectual, and conventional goals, and how this developed over time; (2) whether typical profiles of goal preferences were distinguishable; and (3) how educational goal endorsement could be predicted by socio-demographic, profession-related, and psychological background variables. The results revealed an overall rank order of social > conventional > intellectual goals that was stable over time. Preservice teachers attributed social goals more strongly to family; they attributed intellectual and conventional goals to school. Moreover, we identified three latent classes of goal commitment that changed in size across measurement occasions. We also found small to medium relationships between educational goal preferences regarding socio-demographic background, constructive and transmissive beliefs about teaching, pedagogical and subject-related interests, self-efficacy, and big five personality traits.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

There is general agreement that teachers’ ethos is a crucial component of their professional competence (Baumert & Kunter, 2013; Oser, 1998; Tenorth, 2006; Terhart, 2000). However, a scientific consensus about how to conceptualize and investigate teachers’ ethos empirically has not yet been reached. This is apparent from the diversity of theoretical and empirical approaches (Oser & Biedermann, 2018) that characterizes the contributions in this volume.

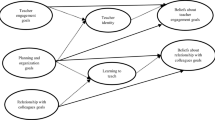

In this chapter, we advance a conceptualization of professional ethos as a system of profession-related values and goals (Bauer & Prenzel, 2013). Such values and goals are related to the diverse aspects of professional practice: they have an impact on, for example, teachers’ perceptions, decisions, interactions, and conditions, but are also affected by experiences of professional situations, reflections, and discussions in professional communities. Therefore, we believe that the proposed conceptualization provides a framework that can integrate more detailed aspects of teachers’ ethos, such as professional ethics or the norms and values that guide instruction.

The main interest of the present chapter is to explore how this theoretical concept can be realized in empirical research approaches. We investigated teachers’ commitment to various educational goals, such as fostering students’ attainment of knowledge and understanding, being ready to learn, and acting socially responsibly. As will be elaborated on later, educational goals describe competences or behavioral dispositions that are societally relevant and that parents and teachers hope to foster in children through educational interventions (Fuhrer, 2009; Stein, 2012; Tarnai, 2010). Educational institutions typically pursue educational goals that have to be interpreted and transposed and thus might be superimposed with the purposive ideas of individual professionals or professional communities.

In this general sense, educational goals represent core values underlying the teaching profession (Baumert & Kunter, 2013; Drahmann et al., 2018; Stein, 2012; Tarnai, 2010). The case made here is that the degree to which teachers as professional actors differentially endorse educational goals indicates whether or not they take responsibility for their attainment by students in school. Therefore, teachers’ commitment to such goals is a manifestation of their comprehensive professional value system, which can be understood as their professional ethos.

Based on this concept, we present data from a longitudinal panel study. In this study, we investigated how students in initial teacher education endorsed three important types of educational goals: intellectual, social competence, and conventional goals. Our research questions addressed (1) the priority (i.e., rank order) of the endorsement of these goals and their attribution to school or family, (2) how this endorsement develops over initial teacher education, and (3) whether goal endorsement can be predicted by socio-demographic, profession-related, and psychological background characteristics of students enrolled in teacher education.

To begin, we elaborate on the concept of teachers’ professional ethos. Then, we discuss the role of educational goals within this context and summarize pertinent research findings.

What Is the Professional Ethos of Teachers?

Generally, the term ethos designates the guiding beliefs, values, or ideals of a person, group, or institution (Merriam-Webster, 2019). Ethos can be analyzed both on a collective and an individual level. Applying this definition to the professional context, professional ethos comprises a unique and distinguishing system of profession-related values, norms, and goals to which professionals within a given community of practice feel committed (Wenger, 1998). Since goals and norms are based on values, we refer to ethos as a professional value system.

Some parts of professional value systems are typically grounded in institutionalized norms and even codified in standards or laws. Other parts represent more or less the shared beliefs of a professional community that are connected with a certain commitment or obligation for professional engagement and actions. It is debatable whether, in the case of teachers, there is one global professional community that shares a basic values system (like the Hippocratic oath taken in medicine) or nested professional communities, depending on national educational systems, subjects, and a range of duties and cultures of teaching. Such values systems are socially shared to a certain degree within a professional community. They are not fixed but evolve continuously according to changing demands and conditions.

Incipient professionals acquire both the institutionalized and evolving values of their community through a socialization process during professional education (Bauer, 2016; Lave & Wenger, 1991). These values provide a framework for establishing what is expected and judged as adequate or inadequate professional performance (Bauer, 2008; Oser et al., 1990). Nevertheless, values, norms, and goals, in the end, have to be interpreted and enacted individually, locally, and situationally by the individual professional. This is a reason why the values underlying professional ethos provide a backdrop that may guide actions and decisions in everyday practice but do not determine them.

Applying this generic definition of ethos to teaching, teachers’ professional ethos relates to the value system underlying their diverse tasks in lessons, examinations, school development, and social interaction with students, colleagues, and parents (Baumert & Kunter, 2013; Harder, 2014; Terhart, 2000). Though the explicit or implicit norms of such a value system provide general guidance in fulfilling these tasks, they also comprise substantial degrees of freedom that necessitate (situational) value-based judgment and decision-making by the individual teacher. According to Oser et al. (1990; Oser, 1998), teachers have a fundamental understanding of the obligations and responsibilities of their profession, both on the collective and individual level. This is constitutive of their professional ethos.

The focus of existing research on teacher ethos has been on professional ethics, with a specific interest in social interactions among teachers and students (Harder, 2014; Oser & Biedermann, 2018). The seminal work by Oser et al. (1990; Oser, 1998), for example, focused on professional ethics and morale and their related responsibilities in the form of caring, just, and truthful teacher behavior. Following this line of research, attempts have been made to measure teachers’ ethos in large-scale assessments, using situational judgment tests anchored in school-related conflict scenarios (Blömeke et al., 2007). However, this approach has not proliferated thus far.

Other approaches have focused on indirect manifestations of ethos in teachers’ instructional and classroom behavior, e.g., in the form of individualized and respectful learning support (Baumert et al., 2010). Such teacher behavior may be indicative of a professional value system in which the teacher commits to fostering students according to their individual needs and interacting with them respectfully. Nevertheless, this operational definition of ethos somewhat blurs the boundaries between proposedly distinguishable components of teachers’ professional competence; this includes their beliefs and values, on the one hand, and their professional knowledge and action routines, on the other (Baumert & Kunter, 2013; Bromme, 2001).

In summary, different lines of research on teachers’ ethos have focused on different types of values and their manifestation in professional practice. Despite their differences, the existing approaches share an understanding that the basis of ethos lies in value commitments that are shared, to a certain degree, within the profession and held and enacted by individual teachers. Our proposal to conceptualize teachers’ ethos as a profession-related value system may help to connect existing research approaches that focus on different sets of values (Bauer & Prenzel, 2013; cf. Drahmann et al., 2018; Harder, 2014) and, thus, advance theoretical considerations. In the following sections, this approach is applied to the analysis of teachers’ educational goals.

Educational Goals as Educational Value Commitments

Educational Goals

Education is inherently a goal-directed activity (Brezinka, 1972; Dewey, 1916). Educational goals describe competences or dispositions that are societally relevant and that parents or teachers hope to foster in children through educational interventions (Fuhrer, 2009; Stein, 2012; Tarnai, 2010). For teachers, educational goals have a generic prescriptive function because many of them are codified in laws and curricula (Drahmann et al., 2018). In terms of Baumert and Kunter’s (2013) framework of teachers’ professional competence, educational goals are also an element of professional beliefs and value commitments. Several characteristics of educational goals are important four our purpose.

First, educational goals are multidimensional. Educational goals address various aspects of children’s cognitive, affective, and social development, such as acquiring broad knowledge in diverse subjects or developing skills needed for successful social interaction. Moreover, educational goals comprise conventional virtues emphasizing conformity and achievement (Tarnai, 2010). This multidimensionality of goals even pervades school subjects. For example, science education does not only aim at the development of scientific knowledge and understanding, but also at related attitudes, motivational orientations, values, beliefs, and strategies (Schiepe-Tiska et al., 2016). Hence, several potentially relevant goals may be differentially salient or even competing in a given situation.

Second, because educational goals – such as comprehensive knowledge – are often quite abstract and decontextualized, they represent general value commitments rather than concrete action goals (Rost & Witt, 1993; Tarnai, 2010; cf. Neyer & Asendorpf, 2018). Such goals tend to be diffuse or fuzzy; it is not easy to define criteria for their attainment. Additionally, educational goals can only indirectly guide teacher behavior because they do not provide any specific information on what has to be done to attain them (Kremer, 1978; Patry & Hofmann, 1998; Tarnai, 2010). Given these characteristics, teachers need to interpret educational goals situationally and make principled decisions as to what goals to focus on and how to attain them. However, teachers may also have stable preferences for specific goals. Making reflective and balanced decisions in this context seems an important aspect of teachers’ professional ethos.

In summary, educational goals have a dual relevance concerning teachers’ professional ethos. First, from a personal perspective, commitments to goals and values are an essential part of a person’s professional competence and identity (Baumert & Kunter, 2013; Drahmann et al., 2018; Thome, 2013). Second, the goals that teachers endorse indicate a scope of the responsibility they are willing to take for their students’ education (cf. Oser, 1998; Rost & Witt, 1993; Tarnai, 2010). This includes, for example, prioritizing and specifying multidimensional goals, but also the attribution of responsibility. For example, a teacher might feel mainly committed to contribute to their students’ intellectual development and see the acquisition of conventional goals as the responsibility of the family.

Empirical Research on Educational Goals

Educational goals are a classic research topic of various disciplines, such as educational philosophy and theory (e.g., Brezinka, 1972; Dewey, 1916), empirical educational research (e.g., Anderson et al., 1990; Drahmann et al., 2018; Patry & Hofmann, 1998; Rich & Almozlino, 1999; Stein, 2012), educational psychology (e.g., Fuhrer, 2009; Rost & Witt, 1993; Tarnai, 2010, 2011), and sociology (e.g., Häder, 1998; Schreiber, 2007; Thome, 2013). Literature from educational philosophy suggests a tendency to include normative approaches, focusing on the definition, justification, and critique of educational goals. In contrast, empirical studies have attempted to analyze descriptively the degree to which the general public, parents, and teachers endorse different types of goals for educating children.

Specific research interests have focused on the internal structure of educational goals and the rank order of goal preferences (for an overview, see Tarnai, 2010). Another approach can be seen in evaluation research that assesses the extent of attainment of explicit goals in educational settings (e.g. Lüftenegger et al., 2016). Moreover, educational goals have served as an indicator of the change of societal value orientations (Häder, 1998; Schreiber, 2007) and family relationships (Huinink et al., 2011) in longitudinal studies. Below, we summarize findings that are relevant to this chapter.

Factor analytic studies on the internal structure of educational goals have led to only partially consistent conclusions, probably due to differences in questionnaire content, participants (e.g., parents vs. teachers), and methods (e.g., ranking vs. rating of goals) (Häder, 1998; Tarnai, 2010, 2011; Stein, 2012). Acknowledging this diversity, there seems to be a consensus that at least three categories of educational goals can be distinguished: (1) intellectual goals relating to the expansion of intellectual capacities and gaining of personal autonomy (e.g., acquiring broad knowledge, power of judgment, curiosity); (2) goals relating to the acquirement of social competence (e.g., respectful and empathic behavior); and (3) conventional goals emphasizing virtues of achievement and conformity (e.g., diligence, orderliness, discipline).

Studies on the prevalence of educational goals in the general population have indicated a shift toward an emphasis on intellectual/autonomy goals over traditional/conventional ones (Anderson et al., 1990; Fuhrer, 2009; Häder, 1998; Tarnai, 2010). While these trends occurred on the population level, individual preferences for educational goals seem to be rather stable over time (Anderson et al., 1990).Footnote 1 A number of studies have focused specifically on teachers’ educational goals (Anderson et al., 1990; Kremer, 1978; Patry & Hofmann, 1998; Rich & Almozlino, 1999). However, most were published pre-millennium. Moreover, few studies have investigated teachers’ educational goals based on larger sample sizes. A notable exception is a recent study by Drahmann et al. (2018) that surveyed teachers’ value orientations (including educational goals) based on a large random sample of German teachers and parents. The authors found that teachers rated the importance of social competence and intellectual goals in school to be relatively higher than conventional goals. Particularly, teachers in the academic track of secondary education (i.e., Gymnasium), as well as younger teachers, emphasized goals that were more closely related to achievement. Moreover, the surveyed teachers and parents agreed that family was the most central actor, concerning students’ value education.

Measurement of educational goals was also part of a teacher survey conducted as a part of the Program of International Student Assessment (PISA) 2003 in Germany (Prenzel et al., 2004).Footnote 2 In this survey, mathematics teachers rated the importance of various educational goals separately for school and family (Ramm et al., 2006). This approach is particularly interesting for the purpose of the present chapter. As argued above, the differential endorsement and attribution of educational goals to school and family provides an indicator of the scope of responsibility that teachers are willing to take for their students’ education. Beyond the absolute rating of goal endorsement, this difference can grant a complementary perspective on teachers’ professional value systems.

Figure 12.1 presents the means of the educational goals from the PISA 2003 teacher sample. The calculations used identical analytic specifications, as in the present study, to enhance comparability (see Analyses). In contrast to the aforementioned studies and in line with Drahmann et al. (2018), the PISA 2003 teachers ranked social competence goals highest, albeit with a higher attribution to family than to school. Interestingly, they rated intellectual/autonomy goals somewhat lower than conventional ones and associated them more closely with school than with family.

Beyond the ranking of goals, previous studies have investigated predictors of goal commitment, particularly the role of socio-demographic variables, such as age, gender, socio-economic and educational status (SES), and regional differences (e.g., eastern versus western Germany). A frequent finding was that persons with higher SES tended to prefer intellectual-autonomy goals over conventional ones (Tarnei, 2010). There is also evidence that teachers with less professional experience and teachers from academic track schools place a stronger emphasis on intellectual-autonomy goals (Anderson et al., 1990; Rich & Almozlino, 1999; Tarnei, 2010).

Surprisingly, little evidence is available regarding how typical psychological background variables, such as intelligence or personality, correlate with goal preferences. Such relationships are plausible, however. For example, a recent meta-analysis on the relationship between the big five personality traits and value commitments (Parks-Leduc et al., 2015) found that openness and extraversion related positively to values of achievement, self-direction, and benevolence, and negatively to conformity and tradition. Conscientiousness showed a similar pattern, though it was unrelated to achievement values. In contrast, agreeableness correlated negatively with achievement and conformity values, but positively with social values like benevolence. Neuroticism seemed to be largely unrelated to any value commitments. Whether such findings transfer to educational goals is uncertain, however, because Parks-Leduc et al. (2015) studied a different set of values.

Finally, the relationship between educational goals endorsement and beliefs about teaching and motivational orientations regarding the profession and teacher education (e.g., interests, self-efficacy) seems plausible but has scarcely been investigated. For example, teachers with a more constructive view of teaching might have different goal preferences than teachers with a transmissive view; the latter probably endorsing conventional goals more strongly (cf. Kremer, 1978).

In summary, existing research on educational goals has identified different goal dimensions and investigated their endorsement in various populations, including teachers. To our knowledge, no studies have analyzed the prevalence and development of educational goals in preservice teachers. Such studies would be important in gaining a better understanding of this aspect of professional development. For this purpose, a person-centered approach (Collins & Lanza, 2010) to investigating goal preferences could complement existing perspectives (cf. Bauer & Mulder, 2013; Bauer et al., 2018). That is, it would be interesting to identify persons with different configurations of goal preferences, next to the traditional dimensional approach that focuses on the absolute endorsement of different types of goals. Taking such a person-centered perspective would also allow for potential qualitative-typological changes to be identified in the course of teacher education, next to quantitative change in goal commitment. Finally, a broader set of predictors warrants investigation, including profession-related, study-related, and psychological variables, next to socio-demographic characteristics.

The Present Study

Based on the discussed concept of ethos, the present study aimed to investigate preservice teachers’ educational goals. Specifically, we addressed the following research questions (RQs). First, we wanted to know how preservice teachers endorse different educational goals (intellectual, social, conventional) and how their attribution to school versus family differs. In this context, we also investigated whether this goal endorsement changes over the course of initial teacher education. Hence, three aspects are in focus: the overall rank order of the commitment to the three educational goal dimensions (RQ1a), the difference in the relative importance of school versus family within each respective educational goal dimension (RQ1b), and changes in the endorsement of the educational goals (RQ1c).

Second, we explored the relative endorsement and development of educational goal preferences on the level of latent classes (Collins & Lanza, 2010). Complementary to RQ1, which addressed the overall sample level, in RQ2, we asked whether different subgroups of preservice teachers could be identified according to differences in their overall goal commitment, their preference for goal dimensions, and the relative importance attributed to school versus family (RQ2a). Moreover, we investigated whether qualitative and quantitative change in this classification occurs over the course of preservice teacher education (RQ2b). Qualitative change occurred in shifts in the profiles of belief endorsement that characterized the classes, i.e., the form of the profiles of class-specific means. Quantitative change occurred in changes in class sizes, i.e., how many participants were classified into the respective classes.

Finally, in RQ3, we investigated whether educational goal endorsement could be predicted based on the relevant background variables of the participating students. To reduce complexity, we focused on predicting educational goals at the first measurement point of the panel. Based on the discussion above, we considered profession-related variables (e.g., beliefs about teaching, pedagogical and subject-related interest as motivation for selecting teaching as a career), psychological variables (e.g., cognitive ability, study-related self-efficacy, big five personality traits), socio-demographic background (e.g., gender, SES), and characteristics of the participants’ study programs (e.g., preparing for teaching in an academic track vs. other tracks of secondary education). This part of the study was mostly exploratory as, due to the few available findings in the literature, we had only tentative expectations concerning the relationships between these variables and the educational goals.

Methods

Data

We analyzed data from the bachelor’s cohort of the PaLea study (Bauer et al., 2010; Kauper et al., in press). PaLea is a multi-wave cohort-sequential panel study of preservice teachers from 13 universities across Germany. The panel surveyed trajectories of professional development on a comprehensive array of variables. The investigated bachelor’s cohort started in the winter term of 2009/10 and was followed until entry into the master’s level, with data collection at approximately half-year intervals. Educational goals were measured at four occasions, covering the time from entry to the study program until the fifth semester (cf. Table 12.1). Of the effective sample at t1, 69% were female; 59% aimed to become teachers in the academic track of secondary education.

Table 12.1 shows the available sample sizes by measurement occasion. As can be seen, a substantial dropout occurred in the transition from t1 to t2 when the data collection mode changed from paper and pencil questionnaires to an online survey. Though the participation rate recovered somewhat after t2, the dropout was still substantial.

To gage selection effects, we conducted a nonresponse analysis comparing dropouts and stayers after t1 on a comprehensive set of variables, including educational goals (SES, cognitive ability, personality, motivational orientations, teacher beliefs, gender, type of study program, and so forth). This analysis revealed overall small effect sizes with a median Cohen’s d of 0.08 and an interquartile range of 0.04–0.14. The two largest effect sizes were still small according to Cohen’s conventions (the stayers had higher values of conscientiousness [d = 0.26] and cognitive ability [d = 0.18]). This indicated that panel mortality, while being of substantial size, did not seem to induce substantial selection bias.

To make efficient use of the available data, we used full information maximum likelihood estimation (Enders, 2010) as a modern missing data technique.

Instruments

Educational Goals

Educational goals were measured in PaLea using a set of 17 items. Participants rated the importance of these goals separately for school and family on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = less important, 4 = extremely important).Footnote 3 These items are identical to the PISA 2003 teacher survey. Unfortunately, the existing documentation (Baumert et al., 2009; Ramm et al., 2006) does not describe the items’ origin and theoretical background clearly. Some data come from the German General Social Survey 1982 (Hagstotz et al., 1983), and the set was adapted and extended for the TIMSS II teacher survey (J. Baumert, personal communication). A more recent application in the current format was used in the German National Educational Panel Study 2008/2009 (Sachse et al., 2012).

Since the present study aimed to compare educational goal commitment across school and family and across time, a measurement model with sufficient measurement invariance properties was required (i.e., scalar invariance; Brown, 2015). Using factor analyses, we selected items to attain a well-fitting and measurement-invariant model. This procedure resulted in a model with three items per goal dimension: (1) conventional goals: persistence and achievement motivation, orderliness and discipline, and readiness to learn; (2) intellectual goals: broad knowledge, intellectual curiosity, and power of political judgment; and (3) social competence goals: sense of social responsibility, respectful and helpful behavior, and appropriate social behavior. The final CFA model provided an acceptable fit to the data, χ2(2032) = 4529.525, p < .001, RMSEA = .018, CFI = .931, SRMR = .060. Findings for the invariance analyses are omitted for brevity and available from the authors. The reliability of the resulting scales was generally acceptable (average Cronbach’s α across time points for school: conventional = .64, intellectual = .58, social = .74; for family: conventional = .60, intellectual = .66, social = .71).

Predictors

The measures for the investigated predictors are listed below. Comprehensive documentation is available in Kauper et al. (2012).

-

Constructive and transmissive views of teaching (α = .73 and .77, respectively)

-

Pedagogical interest and subject-related interest as career choice motivation (α = .83 and .72, respectively) (Pohlmann & Möller, 2010)

-

Study-related self-efficacy (α = .68)

-

Cognitive ability: subtest figural analogies from the cognitive ability test (EAP reliability = .75) (Heller & Perleth, 2000)

-

Big five personality traits: agreeableness (α = .76), conscientiousness (α = .77), neuroticism (α = .64), extraversion (α = .68), openness (α = .53) (Herzberg & Brähler, 2006)

-

SES: Highest International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status (HISEI; Ganzeboom et al., 1992)

-

Gender (male = 1)

-

Teacher education study program (academic track = 1 vs. other = 0)

Analyses

To answer RQ1a and b, we compared latent means across the goal dimensions according to school versus family. For RQ1c, next to descriptive trajectories, we analyzed multi-indicator latent growth curve models. The latter were specified with slope loadings set to represent the months between measurement occasions (Little, 2013).

For RQ2, we conducted latent profile analyses (LPAs) separately for each measurement occasion. A LPA adopts a person-centered approach to analyzing categorical individual differences in terms of classification of persons (Collins & Lanza, 2010). It provides a probability-based assignment of persons to latent classes characterized by their response profiles on the investigated variables. We conducted the LPA on factor scores of the goal dimensions that were obtained from the CFA with invariance restrictions. The decision on the number of classes was based on fit indices (AIC, BIC, aBIC), the LMR-likelihood ratio test, as well as the substantive interpretability of the solution (Masyn, 2013).

Regarding RQ2b, we analyzed descriptive change in the latent class solutions by comparing the form of the profiles and the relative class sizes over time.Footnote 4 For RQ3, we regressed the educational goal variables simultaneously on the predictors in a structural equation model. To reduce model complexity, the predictors were included as manifest mean scores. All analyses were done in Mplus 8.3 using robust MLR estimation to account for non-normality and correcting for the complex sample structure.

Results

Research Question 1: Relative Endorsement of Educational Goals

The estimated means and 95% confidence intervals of educational goal endorsement are plotted in Fig. 12.2. These findings reveal the rank order of goal importance across school and family (RQ1a): in both domains, participants rated social goals highest with a substantial difference in intellectual and conventional goals. In relation to school, conventional goals were rated as somewhat more important than intellectual goals. In contrast, the participants rated intellectual and conventional goals as equally important in relation to family.

Regarding the relative importance of school versus family within each educational goal dimension (RQ2b), the findings indicated that the attainment of intellectual and conventional goals was associated more closely with school. In contrast, participants placed a stronger emphasis on family for social goals. Concerning change (RQ1c), the findings show descriptively that the rank order of educational goal endorsement stayed unchanged over time. This concerns both the rank order of the three dimensions and the relative importance in school versus family. Consequently, the respective slope coefficients of the latent growth curve models were close to zero (Table 12.2; all models fitted the data well; details are omitted here for brevity).

Research Question 2: Latent Classes of Goal Endorsement and their Development

The LPA resulted in a best-fitting solution with three latent classes (RQ2a). Across the four measurement occasions, this solution provided the most parsimonious model that yielded a substantively interpretable and consistent classification, though the fit indices did not provide unequivocal support (table available upon request). The three-class solution also avoided notorious problems (e.g., classes <5%) occurring in solutions with more than three latent classes (cf. Collins & Lanza, 2010). The reliability of the classification was high at each time point, as judged by the entropy values (range .71 < .85). Figure 12.3 depicts the latent mean profiles of the three classes by measurement occasion. Values on the y-axis are mean-centered and indicate deviations from the overall sample average. For interpretation, we inspected the class-specific profiles. For each class, these profiles indicated the overall goal endorsement, rank order, and relative importance in school versus family.

Inspecting the profiles at t1, the most prominent feature of Class 1 was an above-average commitment to all educational goal dimensions. Averaging across school and family, participants in this class tended to assign intellectual goals the highest importance. Finally, they rated the importance of family higher than school, especially for intellectual and conventional goals. We referred to this class as highly committed–intellectually oriented. With about 54% of participants, this was the largest class at t1 (see Table 12.3 for relative class sizes).

The profile of Class 2 was more diverse in terms of the distribution of means. Participants in this class rated social competence goals and conventional goals higher than intellectual goals. This pattern indicates a favor of goals advancing affirmative goals of education, that is, conforming with one’s societal role and behavior expectations (i.e., adequate social behavior, conforming to conventional norms). Moreover, participants in Class 2 assigned school substantially higher importance than family for these goals. We referred to this class as affirmatively oriented (31% of participants).

Finally, Class 3 is best described as demonstrating an overall below-average endorsement of the educational goals. At t1, participants in this class rated intellectual and conventional goals as equally important and somewhat higher than social goals. This preference might indicate an emphasis on cognitive and achievement-related goals. For these goals, school and family were rated as equally important, whereas social goals were more closely associated with school. We tentatively referred to this class as lowly committed–cognitively oriented (15%).

To answer RQ2b, we first checked the consistency of the class profiles and their interpretation over time. As can be seen from Fig. 12.2, the profiles of Class 1 and 2 remained largely stable across the four measurement occasions, despite slight changes. For Class 1, the size of the differences between the six indicator variables varied somewhat, and the distance to the sample average got smaller. However, the interpretation of the profile of Class 1 (i.e., highly committed–intellectual oriented) was consistent over time. The same was true for Class 2 (i.e., affirmatively oriented), though there were minor shifts in the (small) difference between the ratings for school versus family regarding social goals.

For Class 3, there were more notable differences: intellectual and conventional goals were rated as equally important in school and family at t1, but participants assigned a priority to family from t2 onward. Still, the class can best be described as being overall lowly committed and emphasizing cognitive and achievement-related goals.

As a final step, we descriptively checked for changes in the relative class sizes over time. For this purpose, Table 12.3 cross-tabulates the class sizes for t1 and t8. This indicates that more participants fell into Class 1 over time, while the other two classes got smaller.

Research Question 3: Predicting Educational Goal Endorsement

The model with the predictors of educational goal endorsement provided an acceptable fit to the data, χ2(285) = 1465.754, p < .001, RMSEA = .037, CFI = .911, SRMR = .038. The results of the regression are available in Table 12.4. Overall, the predictors explained 16% to 22% of the variance in educational goal endorsement. The individual effects hint at systematic relationships, though most of them are of small to medium size.

Concerning socio-demographic background and study-related characteristics, higher SES and presence of academic track teacher education predicted a higher endorsement of intellectual goals in school and family. There were also some very small effects, indicating that academic track preservice teachers had a slight preference for conventional goals and higher attribution of social goals to family when compared to teachers of other tracks. Moreover, gender had a small effect. Male preservice teachers indicated a higher commitment to intellectual goals in school and family and a somewhat smaller endorsement of social and conventional goals in school. The latter effect was close to zero.

Of the profession-related variables, a constructive view of teaching had consistent positive relationships with intellectual and social competence goals. In contrast, a transmissive view had a medium positive relationship with conventional goals as well as a very slight negative effect on intellectual goals. Moreover, pedagogical interest as a reason for choosing teaching as a career was related to a higher commitment to social goals. Interest in the teaching subjects had a small positive effect on teachers’ commitment to all goals, most strongly on intellectual and conventional goals in school.

Of the achievement-related psychological background variables, self-efficacy predicted higher intellectual goals and, to a lesser degree, conventional goals. Effects of cognitive ability proved to be inconsistent, showing small positive relationships with intellectual goals in school, social goals in family, and conventional goals in both domains. Concerning the big five personality traits, higher openness was positively associated with stronger endorsement of intellectual goals and agreeableness with social goals. Conscientiousness had a small to medium positive effect on conventional goals as well as a small negative effect on intellectual goals. Finally, extraversion and neuroticism were mostly unrelated to educational goals, with indications of a very small negative effect on intellectual goals.

Discussion

In the present study, we introduced the concept of teachers’ professional ethos as a system of profession-related values, norms, and goals. We explored this perspective by analyzing preservice teachers’ commitment to different types of educational goals. Drawing upon data from a large-scale panel study, we investigated the prevalence and development of educational goal endorsement, as well as relevant predictors. The conceptual points and findings presented in this chapter advance the research on teachers’ ethos, which, so far, has focused on professional ethics and their implications for teacher behavior (e.g., Oser & Biedermann, 2018). Conceptualizing ethos more generally as a professional value system, we connected various existing lines of research, providing opportunities to generate new RQs.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the development of educational goal endorsement in preservice teachers. The findings extend existing studies, first, by combining a traditional quantitative dimensional perspective with a person-centered typological approach and, second, by investigating a broader scope of predictors of educational goal commitment (cf. Drahman et al., 2018; Tarnai, 2010). Particularly, we provided evidence for the role of profession-related and psychological background variables, in addition to socio-demographic characteristics.

Concerning the overall rank order of goal commitment (RQ1a), the findings indicate a preference of social > conventional > intellectual goals. This is in line with the PISA 2003 teacher data presented above and Drahmann et al.’s results (2018). In contrast, older studies frequently found teachers to rank intellectual and autonomy goals highest (Tarnei, 2010; Rich & Almozlino, 1999). This divergent finding might indicate a change in teachers’ values, but other explanations related to differences in instrumentation, samples, or cultural/national characteristics are also plausible. Whatever the reasons, it is remarkable that recent studies have found that teachers consider social (and partly conventional) goals to be more important than intellectual ones. Given the challenges today’s teachers face, arising from the increasing diversity of student composition, these preferences might suggest that the pursuit of intellectual goals in the first place requires students to behave in a socially competent manner and adhere to conventional virtues.

The results on the relative goal attribution to school and family (RQ1b) differentiate these findings by showing that preservice teachers attributed social competence goals more strongly to family and intellectual and conventional goals to school. That is, despite clearly prioritizing social goals, preservice teachers allocated the responsibility for attaining them to family (cf. Drahmann et al., 2018). Again, this pattern is consistent with the PISA 2003 results. One possible reason for these findings might be that intellectual and conventional goals have a more direct relation to achievement than social competence goals.

The results regarding the developmental trajectories of goal endorsement (RQ1c) extend the evidence that educational goal preferences are stable over time (Anderson et al., 1990). The present study adds to earlier findings that this stability also applies to the relative attribution of educational goals to school and family. However, the seemingly implied conclusion that teachers’ educational values are largely unaffected by teacher education is premature. Continuing studies should investigate the potential effects of specific opportunities to learn in teacher education more precisely (cf. Schmidt et al., 2011).

The person-centered analyses (RQ2a) provided a complementary perspective by hinting at different profiles of goal preferences; the average tendencies discussed above do not fit all investigated persons in the same way. We found three latent classes characterized by differences in overall goal commitment, rank order of goals, and relative importance in school and family. While the class profiles seemed stable over time, our findings indicate changes in class sizes (RQ2b). Specifically, we found relative growth in class 1, characterized by overall high goal commitment and orientation to intellectual goals, in comparison to the other classes. These findings provide interesting directions for future research. However, cautious interpretation is warranted for two reasons. First, these findings are exploratory and require cross-validation in new samples. Second, normative interpretations of the classes should be avoided because there is no evidence of the potential effects of class membership on relevant outcomes yet.

The results related to the predictors of educational goal endorsement (RQ3) partly corroborated existing research but also delivered new insights. In line with earlier studies, we found that higher SES and preparation for teaching in the academic track of secondary education related to a stronger endorsement of intellectual goals (Anderson et al., 1990; Rich & Almozlino, 1999; Tarnei, 2010). Additionally, males indicated a stronger preference for intellectual goals and conventional goals related slightly more to family than to school.

Beyond such socio-demographic indicators, the present study provides evidence that profession-related and psychological background variables relate to educational goal endorsement. Concerning profession-related variables, a constructive view of teaching suggests a stronger emphasis on intellectual and social competence goals. In contrast, a transmissive view of teaching seems to emphasize conventional goals and has slight negative effects on intellectual ones. Similarly, Kremer (1978) reported consistencies between progressive (intellectual autonomy) and traditional (conventional) educational goals held by elementary school teachers, and their attitudes and classroom behavior. Our findings are also in line with evidence that teachers with a transmissive view of teaching provide less cognitive activation and individualized learning support in the classroom (Voss et al., 2013). Moreover, our finding that a higher pedagogical interest as motivation for career choice relates to a higher commitment to social goals is consistent with evidence that a strong social orientation is a distinguishing characteristic of students in teacher education (Klusmann et al., 2009; Pohlmann & Möller, 2010). Additionally, the positive relationship of subject-related interest with all types of goals might express a higher general engagement and commitment to the aims of the teaching profession.

Concerning psychological background variables, we found achievement-related characteristics to be related to educational goals. Specifically, higher study-related self-efficacy predicted higher intellectual goals and, to some degree, conventional ones. Effects of cognitive ability were very small and inconsistent, however. These findings indicate that teachers’ achievement-related self-perception is more closely related to their goals for the intellectual development of children than their actual cognitive ability. Hence, educational goals seem to depend more on teachers’ mindsets than on tangible abilities.

This interpretation is supported by the results on relationships with the big five personality traits. We found theoretically plausible positive effects of openness on intellectual goals, agreeableness on social competence goals, and conscientiousness on conventional goals. In contrast, extraversion and neuroticism were mostly independent of educational goals. This pattern of findings partly echoes correlations between the big five and general value commitments (Parks-Leduc et al., 2015), as discussed above.

As mentioned, most investigated predictors had quite small effect sizes. This indicates that values constitute a largely separate aspect of personality; however, they have systematic covariations with others (cf. Neyer & Asendorpf, 2018). According to Tarnei (2010), small effect sizes are a frequent plague in research on predictors of educational goals. This is especially the case in studies with rather homogeneous samples (i.e., in specific rather than general population surveys; Tarnei, 2010), such as the present study, which focused on preservice teachers in bachelor’s degree programs in Germany. Despite this limitation, the consistency of many of our findings with prior research adds to their validity. Concerning future research on educational goals—and more broadly, on teachers’ ethos—we conclude that relationships between profession-related beliefs as well as general psychological characteristics should be investigated more deeply.

Another limitation is that, compared to other studies, the present study only analyzed a specific set of educational goals. The selection of items was partly driven by the need to establish a measurement model with sufficient invariance to make sound comparisons across domains (school vs. family) and time. Other potentially relevant aspects of educational goals had to be omitted. This may be seen as a threat to content validity. However, we judge it preferable to analyze a few relevant indicators that satisfy the required measurement properties and allow valid comparisons to be made (Brown, 2015). Moreover, we believe that the three investigated dimensions of educational goals and their respective items cover a relevant core of educational goals also addressed in other studies. Clearly, more theoretical and empirical work on measuring educational goal preferences with adequate reliability and validity is required (Tarnei, 2011).

Finally, the present study only investigated a specific aspect of the professional value system that makes up teachers’ ethos. How educational goal preferences relate to other aspects of teachers’ ethos, such as professional ethics, is an open issue.

Notes

- 1.

This is only a seeming contradiction with the mentioned shift toward intellectual/autonomy goals on the population level. Even when individuals maintain their personal goal preferences, population change can occur over time through a cohort effect (Menard, 2002).

- 2.

Equivalent to the sample of the COACTIV study (Baumert et al., 2013).

- 3.

Unless stated otherwise, all scales used in this study used a 4-point answer format.

- 4.

Latent transition models would have been optimal, but did not converge, probably due to the complexity of the present data.

References

Anderson, D. B., Anderson, A. L. H., Mehrens, W., & Prawat, R. S. (1990). Stability of educational goal orientations held by teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 6, 327–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(90)90025-Z

Bauer, J. (2008). Learning from errors at work. Studies on nurses’ engagement in error related learning activities [Doctoral Dissertation, University of Regensburg]. http://www.opus-bayern.de/uni-regensburg/volltexte/2008/990

Bauer, J. (2016). Professionsbezogene Lern- und Entwicklungsprozesse. Zeitschrift für Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik, 112, 482–500.

Bauer, J., & Mulder, R. H. (2013). Engagement in learning after errors at work: Enabling conditions and types of engagement. Journal of Education and Work, 26, 99–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2011.573776

Bauer, J., & Prenzel, M. (2013 August). Approaches to investigate teachers’ ethos in large scale studies: Exemplary findings on teachers’ educational goals. Paper presented at the 15th biennial conference of the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction (EARLI), Munich, Germany.

Bauer, J., Drechsel, B., Retelsdorf, J., Sporer, T., Rösler, L., Prenzel, M., & Möller, J. (2010). Panel zum Lehramtsstudium – PaLea: Entwicklungsverläufe zukünftiger Lehrkräfte im Kontext der Reform der Lehrerbildung. Beiträge zur Hochschulforschung, 32, 34–55. www.bzh.bayern.de/uploads/media/2-2010-bauer-et-al.pdf

Bauer, J., Gartmeier, M., Wiesbeck, A. B., Moeller, G. E., Karsten, G., Fischer, M. R., & Prenzel, M. (2018). Differential learning gains in professional conversation training: A latent profile analysis of competence acquisition in teacher-parent and physician-patient communication. Learning and Individual Differences, 61, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.11.002

Baumert, J., & Kunter, M. (2013). The COACTIV model of teachers’ professional competence. In M. Kunter, J. Baumert, W. Blum, U. Klusmann, S. Krauss, & M. Neubrand (Eds.), Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers: Results from the COACTIV project (pp. 25–48). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5149-5_2

Baumert, J., Blum, W., Brunner, M., Dubberke, T., Jordan, A., Klusmann, U., et al. (2009). Professionswissen von Lehrkräften, kognitiv aktivierender Mathematikunterricht und die Entwicklung von mathematischer Kompetenz (COACTIV): Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente (Materialien aus der Bildungsforschnung No. 83). Berlin: MPI für Bildungsforschung. http://hdl.handle.net/11858/00-001M-0000-0028-662F-3

Baumert, J., Kunter, M., Blum, W., Brunner, M., Voss, T., Jordan, A., et al. (2010). Teachers’ mathematical knowledge, cognitive activation in the classroom, and student progress. American Educational Research Journal, 47(1), 133–180. https://doi.org/10.3102/2F0002831209345157

Baumert, J., Kunter, M., Blum, W., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., & Neubrand, M. (2013). Professional competence of teachers, cognitively activating instruction, and the development of students’ mathematical literacy (COACTIV). In M. Kunter, J. Baumert, W. Blum, U. Klusmann, S. Krauss, & M. Neubrand (Eds.), Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers: Results from the COACTIV project (pp. 1–21). Boston, MA, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5149-5_1

Blömeke, S., Müller, C., & Felbrich, A. (2007). Empirische Erfassung des professionellen Ethos von zukünftigen Lehrpersonen. Beiträge zur Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung, 25, 86–97. urn:nbn:de:0111-pedocs-136379.

Brezinka, W. (1972). Was sind Erziehungsziele? Zur logischen Analyse eines pädagogischen Grundbegriffs. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 18, 497–550.

Bromme, R. (2001). Teacher expertise. In J. J. Smelser & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 15459–15465). Pergamon.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford.

Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis. Wiley.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. Macmillan.

Drahmann, M., Cramer, C., & Merk, S. (2018). Wertorientierungen und Werterziehung von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern in Deutschland. Obtained 30 July, 2019, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328838643

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. Guilford Press.

Fuhrer, U. (2009). Lehrbuch Erziehungspsychologie (2nd ed.). Huber.

Ganzeboom, H. B. G., De Graaf, P. M., & Treiman, D. J. (1992). A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 21, 1–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-089X(92)90017-B

Häder, M. (1998). Erziehungsziele 1992–1996. In H. Meulemann (Ed.), Werte und nationale Identität im vereinten Deutschland: Erklärungsansätze der Umfrageforschung (pp. 197–212). VS-Verlag.

Hagstotz, W., Kirschner, H.-P., Porst, R., & Prüfer, P. (1983). Methodenbericht: Allgemeine Bevölkerungsumfrage der Sozialwissenschaften – Allbus 1982 (ZUMA research report 1982/21). Mannheim: ZUMA. https://dbk.gesis.org/dbksearch/file.asp?file=ZA1160_mb.pdf

Harder, P. (2014). Werthaltungen und Ethos von Lehrern. University of Bamberg Press.

Heller, K. A., & Perleth, C. (2000). Kognitiver Fähigkeitstest für 4.-12. Klassen, Revision. Hogrefe.

Herzberg, P. Y., & Brähler, E. (2006). Assessing the big-five personality domains via short forms: A cautionary note and a proposal. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 22, 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.22.3.139

Huinink, J., Brüderl, J., Nauck, B., Walper, S., Castiglioni, L., & Feldhaus, M. (2011). Panel analysis of intimate relationships and family dynamics (pairfam): Conceptual framework and design. Zeitschrift für Familienforschung/Journal of Family Research, 23, 77–101. https://www.budrich-journals.de/index.php/zff/article/download/5041/4198

Kauper, T., Retelsdorf, J., Bauer, J., Rösler, L., Möller, J., & Prenzel, M. (2012). PaLea - Panel zum Lehramtsstudium. Skalendokumentation und Häufigkeitsauszählungen des BMBF-Projekts (1. Welle). IPN.

Kauper, T., Bernholt, A., Möller, J., & Köller, O. (Eds.). (in press). Entwicklung professioneller Kompetenzen von Lehramtsstudierenden. Ergebnisse aus dem Panel zum Lehramtsstudium. Waxmann.

Klusmann, U., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Kunter, M., & Baumert, J. (2009). Eingangsvoraussetzungen beim Studienbeginn. Werden die Lehramtskandidaten unterschätzt? Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 23, 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652.23.34.265

Kremer, L. (1978). Teachers’ attitudes toward educational goals as reflected in classroom behavior. Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 993–997. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.70.6.993

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning. Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford.

Lüftenegger, M., Finsterwald, M., Klug, J., Bergsmann, E., van de Schoot, R., Schober, B., & Wagner, P. (2016). Fostering pupils’ lifelong learning competencies in the classroom: Evaluation of a training programme using a multivariate multilevel growth curve approach. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(6), 719–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2015.1077113

Masyn, K. (2013). Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling. In T. D. Little (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods in psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 551–611). Oxford University Press.

Menard, S. (2002). Longitudinal research. Sage.

Merriam-Webster. (2019). Ethos. Retrieved May 2, 2019, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ethos

Neyer, F. J., & Asendorpf, J. (2018). Psychologie der Persönlichkeit. Springer.

Oser, F. (1998). Ethos - die Vermenschlichung des Erfolgs. Zur Psychologie der Berufsmoral von Lehrpersonen. Leske + Budrich.

Oser, F., & Biedermann, H. (2018). The ethos of teachers. Is only a procedural discourse approach a valid model? In A. Weinberger, H. Biedermann, J.-L. Patry, & S. Weyringer (Eds.), Professionals’ ethos and education for responsibility (pp. 23–39). Brill.

Oser, F., Zutavern, M., & Patry, J.-L. (1990). Professionelle Lehrermoral: Das “gelebte Wertesystem” von LehrerInnen und seine Veränderbarkeit. In L.-M. Alisch, J. Baumert, & K. BECK (Eds.), Professionswissen und Professionalisierung (pp. 227–252). TU Braunschweig.

Parks-Leduc, L., Feldman, G., & Bardi, A. (2015). Personality traits and personal values: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19, 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314538548

Patry, J.-L., & Hofmann, F. (1998). Erziehungsziel Autonomie: Anspruch und Wirklichkeit. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 45, 53–66.

Pohlmann, B., & Möller, J. (2010). Fragbogen zur Erfassung der Motivation für die Wahl des Lehramtsstudiums (FEMOLA). Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 24, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1024/1010-0652/a000005

Prenzel, M., Baumert, J., Blum, W., Lehmann, R., Leutner, D., Neubrand, M., et al. (Eds.). (2004). PISA 2003. Der Bildungsstand der Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Waxmann.

Ramm, G., Prenzel, M., Baumert, J., Blum, W., Lehmann, A. C., Leutner, D., et al. (2006). PISA 2003. Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente. Waxmann.

Rich, Y., & Almozlino, M. (1999). Educational goal preferences among new and veteran teachers of sciences and humanities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 15, 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(99)00010-4

Rost, D. H., & Witt, M. (1993). Erziehungsziele von Eltern hochbegabter Kinder. In D. H. Rost (Ed.), Lebensumweltanalyse hochbegabter Kinder (pp. 75–104). Hogrefe.

Sachse, K., Kretschmann, J., Kocaj, A., Köller, O., Knigge, M., & Tesch, B. (2012). IQB-Ländervergleich 2008/2009. Skalenhandbuch zur Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente. IQB.

Schiepe-Tiska, A., Roczen, N., Müller, K., Prenzel, M., & Osborne, J. (2016). Science-related outcomes: Attitudes, motivation, value beliefs, strategies. In S. Kuger, E. Klieme, N. Jude, & D. Kaplan (Eds.), Assessing contexts of learning. An international perspective (pp. 301–329). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45357-6_12

Schmidt, W. H., Cogan, L., & Houang, R. (2011). The role of opportunity to learn in teacher preparation: An international context. Journal of Teacher Education, 62, 138–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487110391987

Schreiber, N. (2007). Zum Stichwort “Bündnis für Erziehung”: Erziehungsziele von Eltern und Erzieherinnen in Kindertageseinrichtungen. Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation, 27, 88–101.

Stein, M. (2012). Erziehungsziele von Eltern in Abhängigkeit sozio-struktureller Merkmale und subjektiver Orientierungen. Eine längsschnittliche internationale Analyse auf Basis der Daten des World Value Surveys. Bildung und Erziehung, 65, 427–444.

Tarnai, C. (2010). Erziehungsziele. In D. H. Rost (Ed.), Handwörterbuch Pädagogische Psychologie (pp. 168–175). Beltz PVU.

Tarnai, C. (2011). Analyse der Bewertung von Erziehungszielen. Ein Vergleich von Rating und Ranking. In C. Tarnai (Ed.), Sozialwissenschaftliche Forschung in Diskurs und Empirie (pp. 51–69). Waxmann.

Tenorth, H.-E. (2006). Professionalität im Lehrerberuf. Ratlosigkeit der Theorie, gelingende Praxis. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 9, 580–597. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-006-0169-y

Terhart, E. (2000). Perspektiven der Lehrerbildung in Deutschland. Weinheim.

Thome, H. (2013). Wandel gesellschaftlicher Wertvorstellungen aus der Sicht der empirischen Sozialforschung. In B. Dietz, C. Neumaier, & A. Rödder (Eds.), Gab es den Wertewandel? Neue Forschungen zum gesellschaftlich-kulturellen Wandel seit den 1960er Jahren (pp. 41–67). Oldenbourg.

Voss, T., Kleickmann, T., Kunter, M., & Hachfeld, A. (2013). Mathematics teachers’ beliefs. In M. Kunter, J. Baumert, W. Blum, U. Klusmann, S. Krauss, & M. Neubrand (Eds.), Cognitive activation in the mathematics classroom and professional competence of teachers: Results from the COACTIV project (pp. 249–271). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5149-5_12

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice. Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bauer, J., Prenzel, M. (2021). For What Educational Goals Do Preservice Teachers Feel Responsible? On Teachers’ Ethos as Professional Values. In: Oser, F., Heinrichs, K., Bauer, J., Lovat, T. (eds) The International Handbook of Teacher Ethos. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73644-6_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73644-6_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-73643-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-73644-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)