Abstract

The paper aims to review the current clinical evidence of various herbal agents as an adjunct treatment in the management of chronic periodontitis patients. Gingivitis and periodontitis are two common infectious inflammatory diseases of the supporting tissues of the teeth and have a multifactorial etiology. An important concern about chronic periodontitis is its association with certain systemic disease. New treatment strategies for controlling the adverse effects of chronic periodontitis have been extensively assessed and practiced in sub-clinical and clinical studies. It has been shown that the phytochemical agents have various therapeutic properties such as anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects which can be beneficial for the treatment of periodontitis. The findings of this review support the adjunctive use of herbal agents in the management of chronic periodontitis. Heterogeneity and limited data may reduce the impact of these conclusions. Future long-term randomized controlled trials evaluating the clinical efficacy of adjunctive herbal therapy to scaling and root planing are needed.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Periodontal disease, with the prevalence of about 20–50% of the global population, is one of the most significant public health concerns in both developing and industrial countries [1]. According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) study, in 2009–2012, nearly half (45.9%) of the United States population aged 30 years and older had periodontitis [2].

One of the main concerns about chronic periodontitis is its association with some systemic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), diabetes, and adverse pregnancy outcomes [1]. It is estimated that 19% increase in the risk of CVDs is related to periodontal disease and this relative risk increases to about 44% among the elderly population [1]. In comparison between the patients with diabetes with no or mild chronic periodontitis, patients with type 2 diabetes suffering from severe periodontitis have 3.2 times greater mortality risk [1]. More interestingly, treatment of the periodontal disease may help in controlling glycemic level in patients with type 2 diabetes [3].

The main etiological agents of periodontal disease are periopathogenic bacteria in the subgingival area [4]. The colonization of microorganisms such as Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg), and Prevotella intermedia initiate the inflammation that can lead to tissues breakdown in the susceptible host [5, 6].

Scaling and root planing (SRP) is an essential and the most common treatment procedure for the management of periodontal infections [7, 8]. It should be considered that SRP may not provide optimal benefits in areas with complex anatomies such as furcations, deep pockets, and developmental grooves [9].

To overcome the limitations of conventional treatment, the use of antimicrobial therapy to complement the outcomes of mechanical debridement has been assessed in clinical studies. Concerns about the systemic application of antimicrobials, such as bacterial resistance, associated adverse effects, and drug interactions, provided the impetus for the development of local antibacterial delivery systems and also finding some alternatives for pharmaceutical agents [10,11,12].

On the other hand, in recent years, it has been shown that the immunological responses of host tissues can be considered as an important factor in progressing periodontal tissue destruction. In this regard, a new concept named “host modulation therapy” emerged in the scientific literature [13]. Based on this approach, the treatment plan should be focused on modifying the inflammatory response of the body with the aim of reducing the destructive aspects of the immune system [14].

Recently, a growing body of evidence showed that nutraceuticals and medicinal compounds isolated from plants have several health benefits to prevent and treat various diseases, particularly dyslipidemia and CVD [15,16,17,18], diabetes mellitus [19,20,21], hypertension [22,23,24], and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [25]. These health benefits of herbal medicine include lipid-modifying, anti-tumor, antioxidant, insulin-sensitizing, anti-steatotic, anti-fibrotic, anti-atherosclerotic, antithrombotic, antidepressant, and antirheumatic, anti-inflammatory, anti-stress oxidative, and antimicrobial activates [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. In dental literature, recent preclinical studies showed anti-inflammatory effects of some of the herbal agents with respect to periodontal tissues [39,40,41,42]. Based on these properties, these phytochemical agents can be considered for host modulation therapy [43, 44]. Furthermore, several studies demonstrated the salient role of some nutraceuticals on decreasing bacterial load of dental and periodontal tissues [32, 45,46,47].

Selection of a right herbal antibacterial agent with an appropriate route of administration is the key point to achieve successful periodontal treatment. Reviewing clinical trials using herbal agents for the treatment of chronic periodontitis may be helpful for developing this concept. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study summarizing the results of the clinical studies regarding the effects of herbal medicine and nutraceuticals on periodontitis. With this background, the present review aims to summarize the current evidence on the application of herbal agents as an adjunct treatment in chronic periodontitis patients (Figs. 1 and 2).

Schematic summary of pathways of the effect of nutraceuticals and herbal bioactive compounds on clinical parameters of periodontal diseases and its potential related mechanisms. SBI Sulcus bleeding index, PPD Probing pocket depth, BOP Bleeding on probing, GI gingival index, IL-1β Interleukin 1β, SOD superoxide dismutase

2 Curcumin

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) is extensively used as an Indian spice and is derived from the rhizomes, a perennial member of the Zingiberaceae family. Lampe and Milobedzka identified and introduced curcumin (diferuloylmethane) as the main bioactive component of turmeric in 1910.

Curcumin has a wide spectrum of biological activities such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, antiviral, and antimicrobial properties. Curcumin modulates the inflammatory response by down-regulating the activity of cyclooxygenase-2, lipoxygenase, and inducible nitric oxide synthase enzymes and inhibits the production of the inflammatory cytokines. Moreover, there are some evidence regarding the effectiveness of curcumin in increasing collagen deposition and improving wound healing.

Based on the abovementioned features, many studies have been done to investigate the efficacy of curcumin in the treatment of periodontal disease. In a clinical trial in 2015, the efficacy of curcumin gel (10 mg/g) with and without photoactivation as an adjunct to scaling and root planing (SRP) in the treatment of chronic periodontitis was assessed. The results of this split-mouth clinical trial showed that the application of curcumin gel is an effective treatment modality as an adjunctive to conventional scaling and root planing. Moreover, the investigators showed that the effects were further enhanced by multiple applications of photodynamic therapy in addition to curcumin gel application [48]. The efficacy of treatment in this trial was evaluated based on clinical and microbiologic parameters. There was a significant reduction in clinical parameters such as the sulcus bleeding index (SBI), probing pocket depth (PPD), and clinical attachment level (CAL) in groups treated with curcumin gel. When compared for microbial parameters, there was a statistically significant reduction with respect to Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) and black pigment producing microorganisms (BPB) after 2 months and 3 months in quadrants in which curcumin gel was applied.

In another study with a larger sample size (30 cases), the efficacy of curcumin gel was compared with the efficacy of chlorhexidine (CHX) gel for the treatment of chronic periodontitis [49]. In this clinical trial, the patients were divided into two groups as control and experimental groups using a split-mouth design. At first, the standard SRP treatment was done for two groups. Following SRP, curcumin gel (2%) was applied in the experimental group and CHX gel (0.2%) in the control group. The main clinical criteria in this study were PPD, sulcus bleeding index (SBI), gingival index (GI), and plaque index (PI). These criteria were recorded at the day of treatment and subsequently after 1 month and 45 days.

Based on the statistical analysis in this clinical trial, all mentioned indices showed a significant reduction in both treatment groups. In comparison between two treatment modalities, the efficacy of curcumin gel was significantly better than CHX in reducing the pathologic parameters of periodontitis. Finally, the authors concluded that the curcumin gel has been shown to be more effective than the CHX gel in the treatment of mild to moderate periodontal pockets.

In another study conducted in 2016, the authors assessed the effect of 0.2% curcumin strip as a local drug delivery in conjunction with SRP for the treatment of chronic periodontitis [50]. In this study, the investigators not only registered the clinical parameters (PI, GI, SBI), but also they assessed the level of superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme, in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF). The results showed that the clinical parameters in both groups were improved and there was no statistically significant difference between groups. However, the level of enzyme in the group treated with the curcumin strip was significantly higher than in the control group. The SOD levels seem to be nearing to the healthy group when the curcumin strip was used as an adjunct to SRP.

In another study, the authors evaluate the level of IL-1β in saliva following treatment [51]. In this clinical trial, periodontal pockets of patients were randomly allocated to two treatment groups. Control group was treated with SRP alone while the experimental group was treated with SRP followed by subgingival application of curcumin gel. The results of this study showed a single application of curcumin gel had limited added benefit over scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. In this study, there was no significant difference between control and experimental groups regarding clinical and biochemical indices. None of the subjects who received curcumin gel in this study experienced any adverse effects.

In 2015 a clinical trial was performed to evaluate the effect of local application of curcumin on the “red complex” periodontal pathogens using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In this split-mouth study 30 patients with chronic periodontitis were treated. The control side received the routine SRP treatment and the test side of the mouth was treated with SRP and application of 10 g curcumin gel subgingivally in the base of the pocket [52].

Based on the clinical results of this study, the mean PPD in the test site was significantly reduced when compared to the control site. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding the CAL parameter. The microbiologic assay (PCR) also shown a significant reduction in P. gingivalis (Pg), Tanerella forsythia (Tf), and Treponema denticola (Td) in the test group compared to the control group. The authors suggested that this significant reduction could be related to the antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antiplaque activity of curcumin.

In another innovative study, the curcumin extract was incorporated into Type I collagen chips and used for the treatment of periodontal pockets [53]. This clinical trial compared the efficiency of CHX chips and indigenous curcumin-based collagen as a local drug delivery system in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. The results showed improvement in all clinical and microbiological indices in both groups. However, at the end of the follow-up period (6 months), CHX group showed greater improvement in all of the clinical and microbiological parameters compared to the curcumin-collagen group.

3 Green Tea

Green tea is a natural product of tea (Camellina sinensis) leaves that is consumed as a beverage worldwide. The active ingredients of green tea are polyphenols. Most of them are catechins (flavan-3-ols), which can be classified into four main groups. The most common type (59%) is epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), followed by epigallocatechin (EGC, 19%), epicatechin-3-gallate (ECG, 13.6%), and epicatechin (EC, 6.4%) [54]. In addition, this compound has antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticarcinogenic properties [55,56,57,58].

Green tea was found to be useful in oral health. In an epidemiological study conducted in 2009, it has been shown that there was a modest inverse association between the regular intake of green tea and periodontal disease [59].

Green tea catechins have an anti-oxidant and anti-bacterial effect on pathogens such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia. The mechanism of action is through the inhibiting effect of EGCG and EGC on cysteine proteases of P. gingivalis [60, 61].

In a recent clinical trial, the effect of drinking green tea adjunct to SRP treatment in periodontitis patients has been investigated [62]. In this trial, 30 patients with chronic periodontitis were randomly divided into two groups. All the patients in the two groups received the first phase of periodontal treatment (SRP). The participants of group A were asked to drink commercial green tea 2 times a day (morning and night) for 6 weeks. The average reduction of PPD and bleeding on probing (BOP) were significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group. However, there was no significant reduction in plaque index in interventional groups compared to the control group.

In another clinical trial, the adjunctive use of green tea dentifrice in periodontitis patients was assessed [63]. In this clinical trial, thirty patients with mild to moderate chronic periodontitis were randomly allocated into two treatment groups, “test” and “control” after initial SRP. The control group was given a commercially available fluoride and triclosan containing dentifrice, while the test group received green tea dentifrice with instructions on the method of brushing. All parameters were recorded at baseline and 4 weeks post-SRP.

In this study, not only the clinical indices were recorded, but also some biochemical parameters such as total antioxidant capacity (TAOC) and glutathione-S-transferase (GST) activity in the gingival crevicular fluid were assessed. At the end of the study period, the test group showed statistically significant improvements in GI, BOP, CAL, TAOC, and GST levels compared to the control group. It should be mentioned that GST activity was increased only in the test group. These results demonstrate the anti-inflammatory effect of green tea when used as an adjunct treatment of periodontitis.

Thermo-reversible sustained-release gel containing green tea was another form of this herbal agent which has been assessed for treatment of chronic periodontitis [64]. Thirty patients with two sites in the contralateral quadrants having a PPD ≥4 were included in this study. Total of 60 periodontal pockets from 30 patients was allocated in two groups. Following the completion of SRP treatment, green tea and placebo gels were applied to the periodontal pockets with a blunted cannula. In this study, the clinical parameters were recorded at the baseline and after 4 weeks of introducing the test or control gel into the pockets. The results showed a significant improvement regarding the clinical parameters (PPD, CAL, GI) in both groups. However, these improvements in all criteria were significantly greater in green tea groups compared to the placebo group.

The local effect of green tea for the treatment of periodontal pockets has been evaluated in another clinical trial. In this investigation, the green tea and placebo strips were randomly placed in the periodontal pockets of patients with diabetes and systemically healthy individuals [65]. The follow-up period in this study was 4 weeks. At the end of the study, the clinical indices (GI, PPD, and CAL) in the test sites of both groups were significantly improved compared to the placebo sites. Moreover, the prevalence of P. gingivalis in periodontal pockets of systemically healthy patients was significantly reduced from baseline (75%) to the fourth week (25%). However, the results showed no significant difference regarding microbiologic parameters in patients with diabetes before and after treatment.

Recently a systematic review has been conducted in this regard. In this review, four papers were included in the meta-analysis. All included studies performed SRP and an adjunct application of either a green tea catechin strip or gel on the test sites. Based on the conclusion of this review, the local application of green tea catechin may result in a beneficial reduction in PPD as compared to scaling and root planing with or without placebo [66]. However, there were high heterogeneity in the studies and some risk of bias related to the included studies. Hence, these data still need to be interpreted with caution.

4 Resveratrol

Resveratrol (3,5,4-trihydroxystilbene) is a polyphenol compound found in red wine, peanuts, apples, and several vegetables [67]. A well-known source of this component is Polygonum cuspidatum. From many years ago, the roots of Polygonum cuspidatum have been used in China and Japan as medicine [68]. Many preclinical and in vitro studies investigated the biological effects of resveratrol. These investigations showed anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, and antimicrobial properties for this agent [67]. Resveratrol may reduce the pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL6, IL-1B, IL8, IL12, and TNF [68]. These anti-inflammatory properties of resveratrol may influence the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Many animal studies assessed the influence of resveratrol administration on experimentally induced periodontitis showing promising results [69, 70]. However, this effect is not yet fully studied, making it difficult to incorporate resveratrol as a therapeutic/preventive agent clinically.

In a human clinical trial, the investigators evaluated the effects of resveratrol supplementation in adjunct with non-surgical periodontal therapy on inflammatory, antioxidant, and periodontal markers in patients with diabetes and chronic periodontitis. In this randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled clinical trial, 43 patients with diabetes suffering from chronic periodontitis were recruited. The subjects were randomly divided into control and intervention groups. In the first step, the phase one periodontal therapy was performed for all of the patients. Then the patients in the intervention and control groups received either 480 mg/d resveratrol or placebo capsules (2 pills) for four weeks. The results of this study showed that in the intervention group, the mean serum level of IL6 was significantly reduced post-intervention. No significant differences were seen in the mean levels of IL6, TNFa, TAC, and CAL between two groups post-intervention.

5 Propolis

Propolis is produced by honey bees from substances extracted from parts of certain plants, buds, and sap [71]. Propolis is a very complex mixture consisting of more than 230 constituents, including flavonoids, cinnamic acids and their esters, caffeic acid and caffeic acid phenethyl esters [72]. With regard to a wide range of biological constituents, propolis as a natural resin has several biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial, antiviral, fungicidal, hepatoprotective, free radical scavenging, immunomodulatory, and anti-glycemic activities [73, 74]. For hundreds of years, propolis was used to improve the health status of numerous diseases, such as mucocutaneous infections of fungal, bacterial and viral etiology, and gastrointestinal disorders [75,76,77]. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) is recently introduced as an important active molecule of propolis; most of its therapeutic properties such as anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial properties are related to this component [78,79,80,81]. Several studies have investigated the effects of this natural compound on periodontal diseases and we have summarized their main outcomes in this review. In a recent randomized controlled clinical trial, a total of 50 patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate-to-severe chronic periodontitis were divided into two groups to receive one propolis capsule (400 mg/day) or a placebo capsule for 6 months. After the intervention, in the propolis group, hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) was significantly reduced both 3 and 6 months after the SRP while there were no changes in the control group. In addition, in the propolis group, periodontal health improved as results showed that mean levels of CML significantly reduced in the intervention group though it did not notably change in the control group [82]. In another study, 20 patients with chronic periodontitis with at least 20 natural teeth were randomly either to the control (20 sites) or intervention (20 sites) groups. Control group treated by SRP alone and in the test group, subgingival placement of propolis was used after treatment with SRP. Local drug delivery was evaluated over SRP alone for a period of one month. Results showed that GI, bleeding index (BI), PPD, and CAL scores were significantly improved in the propolis plus SRP group; these changes were greater compared with the control group. Similar findings were obtained regarding microbiological parameters including Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg), Prevotella intermedia (Pi), and Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn). These findings showed that subgingival delivery of propolis as an adjunct to SRP had beneficial effects on clinical and microbiological parameters in patients with chronic periodontitis [83]. In one study, 34 patients with moderate or severe periodontitis were randomly assigned into two groups to receive a polyherbal mouthwash contained propolis resin extract (1:3), Plantago lanceolata leaves extract (1:10), Salvia officinalis leaves extract (1:1), and 1.75% of essential oils (intervention group) or a placebo mouthwash contained 2 ml of glycerin (sweetening agent), cinnamon and vanilla flavoring agents (control group) for 3 months. At the end of the study, in comparison to the control group, a significant reduction was observed in full-mouth bleeding score (FMBS) and full-mouth plaque score (FMPS). Compared with baseline, at post-intervention, PD and CAL significantly decreased in both groups, while differences between groups were not significant [84]. In another clinical trial, 30 patients with chronic periodontitis were assigned into two groups to receive 20% propolis hydroalcoholic solution 24 after SRP which was followed by one-stage full mouth disinfection (OSFMD) or control group in which patients received only SRP. After 12 weeks, probing depth reduction, reduction of microbiological counts of the periodontopathogens, and attachment gain were significantly higher in the treatment group compared with the control. In addition, PI, GI, BOP, PPD, and CAL significantly decreased in the propolis group compared with the control group [85]. In another study, 20 patients with chronic periodontitis, at first were subjected to scaling and root planing and after two weeks were treated with a hydroalcoholic solution of propolis extract twice a week for 2 weeks, or with a placebo twice a week for 2 weeks, or no additional treatment. At the end of the study, in comparison to the placebo and no-treatment groups, in response to propolis, the total viable counts of anaerobic bacteria were significantly reduced, and the proportion of sites with low levels (≤10 5 cfu/mL) of Porphyromonas gingivalis and the number of sites negative for bleeding on probing were significantly increased [86]. In their study, Tanasiewicz et al. evaluated the effects of propolis on the state of the oral cavity in 80 patients with periodontitis. Patients were assigned into 4 groups as follows: (i) Dental Polis DX toothpaste with propolis content (T), (ii) Dental Polis DX toothpaste without propolis content (G), (iii) Carepolis gel with propolis content (CT), (iv) Carepolis gel without propolis content (CG). After 8 weeks, results indicated that hygienic preparations with a 3% content of ethanol propolis extract efficiently support the removal of dental plaque and improve the state of the marginal periodontium [87]. In another clinical trial, 40 patients with chronic periodontitis were randomized into two groups to receive aloe vera tooth gel or propolis tooth gel. After 3 months of intervention, in aloe vera group, only P. gingivalis significantly reduced though in propolis group all the three red complex microorganisms significantly decreased. In addition, all the clinical parameters (PI, GI, Bleeding on Probing, PPD, and CAL) in both groups significantly reduced [88].

6 Aloe Vera

Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis) belongs to the Liliaceae family, is widely used as a medicinal plant for medicinal and skin oral care properties for several years [89, 90]. It has a variety of minerals and vitamins and has several beneficial health effects such as immunomodulatory, antiviral, antitumor, and anti-inflammatory, anti-aging, and antioxidant properties [89,90,91]. In addition, aloe vera has a beneficial effect on wound healing and helps in treating various lesions in the oral cavity [91]. Totally, aloe vera has attracted significant attention in the field of dentistry as a natural and safe product in the treatment of a various oral and dental diseases including lichen planus, oral submucous fibrosis, recurrent aphthous stomatitis, alveolar osteitis, and periodontitis [89,90,91,92,93,94]. Due to the several unique properties of aloe vera, particularly anti-septic and anti-inflammation, anti-viral, and anti-fungal properties [90, 91], several studies assessed its effectiveness on patients with periodontitis, which we have summarized here. In a randomized, controlled clinical trial a total of 90 volunteers with moderate-to-severe chronic periodontitis were randomized to three groups to treat with (i) SRP+ placebo gel; (ii) SRP + 1% metformin gel; and (iii) SRP + aloe vera gel. After 12 months, a significant improvement was observed in GI, BOP, PPD, and CAL in all the groups. However, compared to the placebo group, in the metformin and aloe vera groups, PPD reduction, CAL gain, and percentage of bone fill were greater [95]. In another study, 90 chronic periodontitis patients with class II furcation defects to three groups to treat with (i) SRP plus placebo gel; (ii) SRP plus 1% alendronate gel; and (iii) SRP plus aloe vera gel. After 12 months, a significant decrease in PD, relative vertical clinical attachment level (RVCAL), relative horizontal clinical attachment level (RHCAL), and gains were observed which were greater in the alendronate and aloe vera groups compared to the placebo group. Furthermore, a significantly greater change was also observed in Defect depth reduction (DDR) in the alendronate and aloe vera groups compared to the placebo group [96]. In their study, Moghaddam et al. assessed the effects of aloe vera gel as an adjunct to SRP for the treatment of chronic periodontitis. A total of 20 patients with moderate to severe chronic periodontitis were randomized to treatment with SRP (control group), or SRP combined with aloe vera gel (intervention group). After 60 days, the differences regarding PI were not significant between groups, GI and PD significantly reduced in both groups; however, the reduction was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group [97].

7 Other Nutraceuticals

Scrophularia striata is a plant species that belongs to Srophulariaceae family and has been used in traditional medicine from several years ago. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effect of S. striata has been shown in previous studies [98, 99]. In a recent randomized clinical trial, the effect of S. striata mouthwash in the treatment of chronic periodontitis has been tested [100]. In this study, 50 patients with chronic periodontitis were randomly assigned in two groups. A group of patients used Irsha mouthwash (Iranian form of Listerine) and another group were given S. striata mouthwash and asked them to wash their mouth with 15 ml mouthwash for 30 s each night. The results showed that all the clinical parameters (plaque index, gingival bleeding, and probing depth) and also microbiological index (number of Streptococcus mutans) were improved in the test group compared with the control group.

The cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait) is a native North American fruit that has recently received considerable attention in the treatment of infectious diseases [101,102,103]. The red cranberry extract is a rich source of various classes of potentially bioactive phenolic compounds which have biological properties and may be beneficial for the treatment of periodontal diseases [104]. There are several in vitro studies in the literature showing the antimicrobial effect of cranberry against periopathogens [105,106,107,108]. On the other hand, some in vitro studies showed anti-inflammatory effects of this pulpy and sour fruit which may be beneficial in controlling periodontitis [109,110,111,112]. In a randomized clinical trial, 41 patients who have both diabetes and chronic periodontitis were recruited. Results of this study showed that the consumption of cranberry juice adjunct with nonsurgical periodontal treatment could significantly improve periodontal status in patients with diabetes and periodontitis [113].

Āmla (Emblica officinalis) is another medical plant indigenous to tropical and subtropical regions of South-east Asia. This plant has various therapeutic effects. Previous studies, about Emblica officinalis, showed a wide array of biologic effects such as antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antioxidant, and immune-modulatory properties [114,115,116,117]. The antimicrobial property of E. officinalis fruit is attributed mainly to tannins, phenols, saponins, and flavonoids [118]. The effect of subgingivally delivered 10% Emblica officinalis gel as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis has been investigated in a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial [119]. In this study, 46 patients suffering from chronic periodontitis (528 sites) were randomly assigned to control and test groups. Patients in the control group only received standard SRP treatment but the patients in the test group received both SRP and 10% E. officinalis gel applied in their periodontal pockets. The results showed that locally delivered 10% E. officinalis sustained release gel used as an adjunct to SRP may be more effective in reducing inflammation and periodontal destruction in patients with chronic periodontitis when compared with SRP alone [119]. In another clinical study, the application of E. officinalis irrigation adjunct to SRP was tested. The result demonstrated significantly greater reductions in the mean PI, PPD, and BOP but a greater mean CAL at 3 months post-therapy in the test group than in the negative control group (p < 0.05) [120].

It has been shown that periodontitis is inversely related to plasma vitamin C levels [121,122,123,124]. Rich sources of vitamin C such as green fruits and vegetables may play an important role to treat periodontitis [122, 125, 126]. Kiwifruits are one of the richest dietary sources of vitamin C as green kiwifruit contains 93 mg of vitamin C per 100 g fruit. In a clinical trial study, this hypothesis has been tested [127]. In this single-centered randomized, parallel design, clinical trial with a 5-month follow-up, 48 patients with chronic periodontitis were assigned to two groups. The patients in the test group consumed two kiwifruits/day for 5 months and the control patients did not consume kiwifruits. After two months, all the patients received initial periodontal treatments. The results showed that the test group had significantly greater reductions of bleeding, plaque, and attachment loss than the control group. Systemic biomarkers and vital signs did not show clinically relevant differences between the test and control groups [127].

8 Conclusion

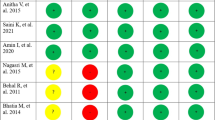

The results from animal and subclinical studies previously have shown a wide array of biological properties for herbal agents. The main biological properties of these agents are antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory effects. Also, there are a large number of original investigations regarding the subclinical effects of natural phytochemicals on periodontal tissues, though the clinical studies in this regard are rare. The purpose of this paper was to review the clinical trials of herbal anti-inflammation and antibacterial agents used as an adjunct therapy for the treatment of chronic periodontitis (Table 1). Based on the results, some of the agents such as curcumin, green tea, propolis, and aloe vera have been shown significant clinical effects in good numbers of clinical trials. However, some other herbal agents such as resveratrol, cranberry, and Emblica officinalis have been tested in very few clinical studies. The main clinical parameters which have been measured in the studies were sulcus bleeding index (SBI), probing pocket depth (PPD), and clinical attachment level (CAL). All of these parameters have been changed positively in response to using these herbal remedies. For future studies, it would be better to investigate not only the clinical indices but also the immunological parameters of chronic periodontitis. Based on the proven biological effects of herbal agents, the hypothesis of applying them as host modulation therapy can be considered for the future. In this regard, larger randomized clinical trials are necessary for developing these concepts in the future. Altogether, the results of clinical trials have considered positive effects for using these natural agents as adjunctive therapy for the treatment of chronic periodontitis. However, more clinical trials are required for the investigation of the appropriate route of administration and optimal doses of the products for the treatment of various stages of chronic periodontitis.

Conflict of interests

None

References

Nazir, M. A. (2017). Prevalence of periodontal disease, its association with systemic diseases and prevention. International Journal of Health Sciences, 11(2), 72.

Eke, P. I., Dye, B. A., Wei, L., Slade, G. D., Thornton-Evans, G. O., Borgnakke, W. S., et al. (2015). Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. Journal of Periodontology, 86(5), 611–622.

Sabharwal, A., Gomes-Filho, I. S., Stellrecht, E., & Scannapieco, F. A. (2018). Role of periodontal therapy in management of common complex systemic diseases and conditions: An update. Periodontology 2000, 78(1), 212–226.

Deng, Z. L., & Szafranski, S. P. (2017). Dysbiosis in chronic periodontitis: Key microbial players and interactions with the human host. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 3703.

Mysak, J., Podzimek, S., Sommerova, P., Lyuya-Mi, Y., Bartova, J., Janatova, T., et al. (2014). Porphyromonas gingivalis: Major periodontopathic pathogen overview. Journal of Immunology Research, 2014476068.

Holt, S. C., & Ebersole, J. L. (2005). Porphyromonas gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia: The “red complex”, a prototype polybacterial pathogenic consortium in periodontitis. Periodontology 2000, 2000, 3872–3122.

Deas, D. E., Moritz, A. J., Sagun, R. S., Jr., Gruwell, S. F., & Powell, C. A. (2016). Scaling and root planing vs. conservative surgery in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. Periodontology 2000, 71(1), 128–139.

Smiley, C. J., Tracy, S. L., Abt, E., Michalowicz, B. S., John, M. T., Gunsolley, J., et al. (2015). Systematic review and meta-analysis on the nonsurgical treatment of chronic periodontitis by means of scaling and root planing with or without adjuncts. Journal of the American Dental Association, 146(7), 508–524.e505.

Herrera, D., Sanz, M., Jepsen, S., Needleman, I., & Roldan, S. (2002). A systematic review on the effect of systemic antimicrobials as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in periodontitis patients. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 29(Suppl), 3136–3159. discussion 160-132.

Jepsen, K., & Jepsen, S. (2016). Antibiotics/antimicrobials: Systemic and local administration in the therapy of mild to moderately advanced periodontitis. Periodontology 2000, 71(1), 82–112.

Szulc, M., Zakrzewska, A., & Zborowski, J. (2018). Local drug delivery in periodontitis treatment: A review of contemporary literature. Dental and Medical Problems, 55(3), 333–342.

Rovai, E. S., Souto, M. L., Ganhito, J. A., Holzhausen, M., Chambrone, L., & Pannuti, C. M. (2016). Efficacy of local antimicrobials in the non-surgical treatment of patients with periodontitis and diabetes: A systematic review. Journal of Periodontology, 87(12), 1406–1417.

Preshaw, P. M. (2018). Host modulation therapy with anti-inflammatory agents. Periodontology 2000, 76(1), 131–149.

Golub, L. M., & Lee, H. M. (2020). Periodontal therapeutics: Current host-modulation agents and future directions. Periodontology 2000, 82(1), 186–204.

Alissa, E. M., & Ferns, G. A. (2012). Functional foods and nutraceuticals in the primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Journal of nutrition and metabolism, 2012.

Ramaa, C., Shirode, A., Mundada, A., & Kadam, V. (2006). Nutraceuticals-an emerging era in the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, 7(1), 15–23.

Zuchi, C., Ambrosio, G., Lüscher, T. F., & Landmesser, U. (2010). Nutraceuticals in cardiovascular prevention: Lessons from studies on endothelial function. Cardiovascular Therapeutics, 28(4), 187–201.

Badimon, L., Vilahur, G., & Padro, T. (2010). Nutraceuticals and atherosclerosis: human trials. Cardiovascular Therapeutics, 28(4), 202–215.

McCarty, M. F. (2005). Nutraceutical resources for diabetes prevention–an update. Medical Hypotheses, 64(1), 151–158.

Davì, G., Santilli, F., & Patrono, C. (2010). Nutraceuticals in diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Cardiovascular Therapeutics, 28(4), 216–226.

Bahadoran, Z., Mirmiran, P., & Azizi, F. (2013). Dietary polyphenols as potential nutraceuticals in management of diabetes: A review. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 12(1), 43.

Houston, M. (2014). The role of nutrition and nutraceutical supplements in the treatment of hypertension. World Journal of Cardiology, 6(2), 38.

Houston, M. C. (2005). Nutraceuticals, vitamins, antioxidants, and minerals in the prevention and treatment of hypertension. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 47(6), 396–449.

Houston, M. C. (2010). Nutrition and nutraceutical supplements in the treatment of hypertension. Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy, 8(6), 821–833.

Bagherniya, M., Nobili, V., Blesso, C. N., & Sahebkar, A. (2018). Medicinal plants and bioactive natural compounds in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A clinical review. Pharmacological Research, 130, 213–240.

Lee, H.-Y., Kim, S.-W., Lee, G.-H., Choi, M.-K., Chung, H.-W., Lee, Y.-C., et al. (2017). Curcumin and Curcuma longa L. extract ameliorate lipid accumulation through the regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum redox and ER stress. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 6513.

Teymouri, M., Pirro, M., Johnston, T.P., & Sahebkar, A. (2017). Curcumin as a multifaceted compound against human papilloma virus infection and cervical cancers: A review of chemistry, cellular, molecular, and preclinical features. BioFactors, 43(3), 331–346.

Panahi, Y., Khalili, N., Sahebi, E., Namazi, S., Simental-Mendía, L.E., Majeed, M., et al. (2018). Effects of Curcuminoids Plus Piperine on Glycemic, Hepatic and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Drug Research, 68(7), 403–409.

Ghandadi, M., & Sahebkar, A. (2017). Curcumin: An effective inhibitor of interleukin-6. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 23(6), 921–931.

Zorofchian Moghadamtousi, S., Abdul Kadir, H., Hassandarvish, P., Tajik, H., Abubakar, S., & Zandi, K. (2014). A review on antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal activity of curcumin. BioMed Research International, 2014.

Bazvand, L., Aminozarbian, M. G., Farhad, A., Noormohammadi, H., Hasheminia, S. M., & Mobasherizadeh, S. (2014). Antibacterial effect of triantibiotic mixture, chlorhexidine gel, and two natural materials Propolis and Aloe vera against Enterococcus faecalis: An ex vivo study. Dental Research Journal, 11(4), 469.

Dziedzic, A., Kubina, R., Wojtyczka, R. D., Kabała-Dzik, A., Tanasiewicz, M., & Morawiec, T. (2013). The antibacterial effect of ethanol extract of polish propolis on mutans streptococci and lactobacilli isolated from saliva. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2013.

Al-Okbi, S. Y. (2014). Nutraceuticals of anti-inflammatory activity as complementary therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Toxicology and Industrial Health, 30(8), 738–749.

Tapas, A. R., Sakarkar, D., & Kakde, R. (2008). Flavonoids as nutraceuticals: A review. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research, 7(3), 1089–1099.

Iranshahi, M., Sahebkar, A., Hosseini, S. T., Takasaki, M., Konoshima, T., & Tokuda, H. (2010). Cancer chemopreventive activity of diversin from Ferula diversivittata in vitro and in vivo. Phytomedicine, 17(3–4), 269–273.

Momtazi, A. A., Derosa, G., Maffioli, P., Banach, M., & Sahebkar, A. (2016). Role of microRNAs in the therapeutic effects of curcumin in non-cancer diseases. Molecular Diagnosis and Therapy, 20(4), 335–345.

Panahi, Y., Ahmadi, Y., Teymouri, M., Johnston, T.P., & Sahebkar, A. (2018). Curcumin as a potential candidate for treating hyperlipidemia: A review of cellular and metabolic mechanisms. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 233(1), 141–152.

Ghasemi, F., Shafiee, M., Banikazemi, Z., Pourhanifeh, M.H., Khanbabaei, H., Shamshirian, A., et al. (2019). Curcumin inhibits NF-kB and Wnt/β-catenin pathways in cervical cancer cells. Pathology Research and Practice, 215(10), art. no. 152556

Moro, M., Silveira Souto, M., Franco, G., Holzhausen, M., & Pannuti, C. (2018). Efficacy of local phytotherapy in the nonsurgical treatment of periodontal disease: A systematic review. Journal of Periodontal Research, 53(3), 288–297.

Ambili, R., Janam, P., Babu, P. S., Prasad, M., Vinod, D., Kumar, P. A., et al. (2017). An ex vivo evaluation of the efficacy of andrographolide in modulating differential expression of transcription factors and target genes in periodontal cells and its potential role in treating periodontal diseases. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 196, 160–167.

Chaturvedi, T. (2009). Uses of turmeric in dentistry: An update. Indian Journal of Dental Research, 20(1), 107.

Nagpal, M., & Sood, S. (2013). Role of curcumin in systemic and oral health: An overview. Journal of Natural Science, Biology, and Medicine, 4(1), 3.

Shetty, S., Bose, A., Sridharan, S., Satyanarayana, A., & Rahul, A. (2013). A clinico-biochemical evaluation of the role of a herbal (Ayurvedic) immunomodulator in chronic periodontal disease: a pilot study. Oral Health and Dental Management, 12(2), 95–104.

de Sousa, M. B., Júnior, J. O. C. S., Barbosa, W. L. R., da Silva Valério, E., da Mata Lima, A., de Araújo, M. H., et al. (2016). Pyrostegia venusta (Ker Gawl.) miers crude extract and fractions: prevention of dental biofilm formation and immunomodulatory capacity. Pharmacognosy Magazine, 12(Suppl 2), S218.

Araújo, N. C., Fontana, C. R., Bagnato, V. S., & Gerbi, M. E. M. (2012). Photodynamic effects of curcumin against cariogenic pathogens. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery, 30(7), 393–399.

Izui, S., Sekine, S., Maeda, K., Kuboniwa, M., Takada, A., Amano, A., et al. (2016). Antibacterial activity of curcumin against periodontopathic bacteria. Journal of Periodontology, 87(1), 83–90.

Parolia, A., Thomas, M. S., Kundabala, M., & Mohan, M. (2010). Propolis and its potential uses in oral health. International Journal of Medicine and Medical Science, 2(7), 210–215.

Sreedhar, A., Sarkar, I., Rajan, P., Pai, J., Malagi, S., Kamath, V., et al. (2015). Comparative evaluation of the efficacy of curcumin gel with and without photo activation as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A split mouth clinical and microbiological study. Journal of Natural Science, Biology, and Medicine, 6(Suppl 1), S102.

Hugar, S. S., Patil, S., Metgud, R., Nanjwade, B., & Hugar, S. M. (2016). Influence of application of chlorhexidine gel and curcumin gel as an adjunct to scaling and root planing: A interventional study. Journal of Natural Science, Biology, and Medicine, 7(2), 149.

Elavarasu, S., Suthanthiran, T., Thangavelu, A., Alex, S., Palanisamy, V. K., & Kumar, T. S. (2016). Evaluation of superoxide dismutase levels in local drug delivery system containing 0.2% curcumin strip as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in chronic periodontitis: A clinical and biochemical study. Journal of Pharmacy & Bioallied Sciences, 8(Suppl 1), S48.

Kaur, H., Grover, V., Malhotra, R., & Gupta, M. (2019). Evaluation of curcumin gel as adjunct to scaling & root planing in management of periodontitis-randomized clinical & biochemical investigation. Infectious Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-Infectious Disorders), 19(2), 171–178.

Nagasri, M., Madhulatha, M., Musalaiah, S., Kumar, P. A., Krishna, C. M., & Kumar, P. M. (2015). Efficacy of curcumin as an adjunct to scaling and root planning in chronic periodontitis patients: A clinical and microbiological study. Journal of Pharmacy & Bioallied Sciences, 7(Suppl 2), S554.

Gottumukkala, S. N., Sudarshan, S., & Mantena, S. R. (2014). Comparative evaluation of the efficacy of two controlled release devices: Chlorhexidine chips and indigenous curcumin based collagen as local drug delivery systems. Contemporary Clinical Dentistry, 5(2), 175.

McKay, D. L., & Blumberg, J. B. (2002). The role of tea in human health: An update. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 21(1), 1–13.

Taguri, T., Tanaka, T., & Kouno, I. (2004). Antimicrobial activity of 10 different plant polyphenols against bacteria causing food-borne disease. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 27(12), 1965–1969.

Cao, G., Sofic, E., & Prior, R. L. (1996). Antioxidant capacity of tea and common vegetables. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 44(11), 3426–3431.

Cooper, R., Morré, D. J., & Morré, D. M. (2005). Medicinal benefits of green tea: part II. Review of anticancer properties. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 11(4), 639–652.

Donà, M., Dell’Aica, I., Calabrese, F., Benelli, R., Morini, M., Albini, A., et al. (2003). Neutrophil restraint by green tea: Inhibition of inflammation, associated angiogenesis, and pulmonary fibrosis. The Journal of Immunology, 170(8), 4335–4341.

Kushiyama, M., Shimazaki, Y., Murakami, M., & Yamashita, Y. (2009). Relationship between intake of green tea and periodontal disease. Journal of Periodontology, 80(3), 372–377.

Okamoto, M., Sugimoto, A., Leung, K. P., Nakayama, K., Kamaguchi, A., & Maeda, N. (2004). Inhibitory effect of green tea catechins on cysteine proteinases in Porphyromonas gingivalis. Oral Microbiology and Immunology, 19(2), 118–120.

Okamoto, M., Leung, K. P., Ansai, T., Sugimoto, A., & Maeda, N. (2003). Inhibitory effects of green tea catechins on protein tyrosine phosphatase in Prevotella intermedia. Oral Microbiology and Immunology, 18(3), 192–195.

Taleghani, F., Rezvani, G., Birjandi, M., & Valizadeh, M. (2018). Impact of green tea intake on clinical improvement in chronic periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Stomatology, Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 119(5), 365–368.

Hrishi, T., Kundapur, P., Naha, A., Thomas, B., Kamath, S., & Bhat, G. (2016). Effect of adjunctive use of green tea dentifrice in periodontitis patients–A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. International Journal of Dental Hygiene, 14(3), 178–183.

Chava, V. K., & Vedula, B. D. (2013). Thermo-reversible green tea catechin gel for local application in chronic periodontitis: A 4-week clinical trial. Journal of Periodontology, 84(9), 1290–1296.

Gadagi, J. S., Chava, V. K., & Reddy, V. R. (2013). Green tea extract as a local drug therapy on periodontitis patients with diabetes mellitus: A randomized case–control study. Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology, 17(2), 198.

Gartenmann, S., Yv, W., Steppacher, S., Heumann, C., Attin, T., & Schmidlin, P. R. (2019). The effect of green tea as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in non-surgical periodontitis therapy: A systematic review. Clinical Oral Investigations, 23(1), 1–20.

Andrade, E. F., Orlando, D. R., Araújo, A. M. S. A., de Andrade, J. N. B. M., Azzi, D. V., de Lima, R. R., et al. (2019). Can resveratrol treatment control the progression of induced periodontal disease? A systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Nutrients, 11(5), 953.

Rizzo, A., Bevilacqua, N., Guida, L., Annunziata, M., Carratelli, C. R., & Paolillo, R. (2012). Effect of resveratrol and modulation of cytokine production on human periodontal ligament cells. Cytokine, 60(1), 197–204.

Corrêa, M. G., Absy, S., Tenenbaum, H., Ribeiro, F. V., Cirano, F. R., Casati, M. Z., et al. (2019). Resveratrol attenuates oxidative stress during experimental periodontitis in rats exposed to cigarette smoke inhalation. Journal of Periodontal Research, 54(3), 225–232.

Bhattarai, G., Poudel, S. B., Kook, S.-H., & Lee, J.-C. (2016). Resveratrol prevents alveolar bone loss in an experimental rat model of periodontitis. Acta Biomaterialia, 29, 398–408.

Sanghani, N. N., Shivaprasad, B., & Savita, S. (2014). Health from the hive: Propolis as an adjuvant in the treatment of chronic periodontitis-a clinicomicrobiologic study. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, 8(9), ZC41.

Czyżewska, U., Konończuk, J., Teul, J., Drągowski, P., Pawlak-Morka, R., Surażyński, A., et al. (2015). Verification of chemical composition of commercially available propolis extracts by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis. Journal of Medicinal Food, 18(5), 584–591.

Armutcu, F., Akyol, S., Ustunsoy, S., & Turan, F. F. (2015). Therapeutic potential of caffeic acid phenethyl ester and its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 9(5), 1582–1588.

Zhu, W., Chen, M., Shou, Q., Li, Y., & Hu, F. (2011). Biological activities of Chinese propolis and Brazilian propolis on streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes mellitus in rats. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2011.

Nolkemper, S., Reichling, J., Sensch, K. H., & Schnitzler, P. (2010). Mechanism of herpes simplex virus type 2 suppression by propolis extracts. Phytomedicine, 17(2), 132–138.

Coelho, L., Bastos, E., Resende, C. C., Sanches, B., Moretzsohn, L., Vieira, W., et al. (2007). Brazilian green propolis on Helicobacter pylori infection. A pilot clinical study. Helicobacter, 12(5), 572–574.

Santos, V., Pimenta, F., Aguiar, M., Do Carmo, M., Naves, M., & Mesquita, R. (2005). Oral candidiasis treatment with Brazilian ethanol propolis extract. Phytotherapy Research: An International Journal Devoted to Pharmacological and Toxicological Evaluation of Natural Product Derivatives, 19(7), 652–654.

Lima, V. N., Oliveira-Tintino, C. D., Santos, E. S., Morais, L. P., Tintino, S. R., Freitas, T. S., et al. (2016). Antimicrobial and enhancement of the antibiotic activity by phenolic compounds: Gallic acid, caffeic acid and pyrogallol. Microbial Pathogenesis, 99, 56–61.

Merkl, R., HRádkoVá, I., Filip, V., & ŠMIdRkal, J. (2010). Antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of phenolic acids alkyl esters. Czech Journal of Food Sciences, 28(4), 275–279.

El-Sharkawy, H. M., Anees, M. M., & Van Dyke, T. E. (2016). Propolis improves periodontal status and glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic periodontitis: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Periodontology, 87(12), 1418–1426.

Tolba, M. F., Azab, S. S., Khalifa, A. E., Abdel-Rahman, S. Z., & Abdel-Naim, A. B. (2013). Caffeic acid phenethyl ester, a promising component of propolis with a plethora of biological activities: A review on its anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, hepatoprotective, and cardioprotective effects. IUBMB Life, 65(8), 699–709.

Borgnakke, W. S. (2017). Systemic propolis (adjuvant to nonsurgical periodontal treatment) May aid in glycemic control and periodontal health in type 2 diabetes of long duration. The Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice, 17(2), 132–134.

Sanghani, N. N., & Bm, S. (2014). Health from the hive: propolis as an adjuvant in the treatment of chronic periodontitis – A clinicomicrobiologic study. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 8(9), Zc41–Zc44.

Sparabombe, S., Monterubbianesi, R., Tosco, V., Orilisi, G., Hosein, A., Ferrante, L., et al. (2019). Efficacy of an all-natural polyherbal mouthwash in patients with periodontitis: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Physiology, 10632.

Pundir, A. J., Vishwanath, A., Pundir, S., Swati, M., Banchhor, S., & Jabee, S. (2017). One-stage full mouth disinfection using 20% propolis hydroalcoholic solution: A clinico-microbiologic study. Contemporary Clinical Dentistry, 8(3), 416.

Coutinho, A. (2012). Honeybee propolis extract in periodontal treatment: A clinical and microbiological study of propolis in periodontal treatment. Indian Journal of Dental Research, 23(2), 294.

Tanasiewicz, M., Skucha-Nowak, M., Dawiec, M., Król, W., Skaba, D., & Twardawa, H. (2012). Influence of hygienic preparations with a 3% content of ethanol extract of brazilian propolis on the state of the oral cavity. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 21(1), 81–92.

Kumar, A., Sunkara, M. S., Pantareddy, I., & Sudhakar, S. (2015). Comparison of plaque inhibiting efficacies of Aloe vera and propolis tooth gels: A randomized PCR study. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research: JCDR, 9(9), ZC01.

Tanwar, R., Gupta, J., Asif, S., Panwar, R., & Heralgi, R. (2011). Aloe Vera and its uses in Dentistry. Indian Journal of Dental Advancements, 3(4), 656–658.

Mangaiyarkarasi, S., Manigandan, T., Elumalai, M., Cholan, P. K., & Kaur, R. P. (2015). Benefits of Aloe vera in dentistry. Journal of Pharmacy & Bioallied Sciences, 7(Suppl 1), S255.

Sajjad, A., & Subhani Sajjad, S. (2014). Aloe vera: An ancient herb for modern dentistry—A literature review. Journal of Dental Surgery, 2014.

Neena, I. E., Ganesh, E., Poornima, P., & Korishettar, R. (2015). An ancient herb aloevera in dentistry: A review. Journal of Oral Research and Review, 7(1), 25.

Subhash, A. V., Suneela, S., Anuradha, C., Bhavani, S., & Babu, M. S. M. (2014). The role of Aloe vera in various fields of medicine and dentistry. Journal of Orofacial Sciences, 6(1), 5.

Subramaniam, T., Subramaniam, A., Chowdhery, A., Das, S., & Gill, M. (2014). Versatility of Aloe vera in Dentistry-A review. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences, 13(10), 98–102.

Kurian, I. G., Dileep, P., Ipshita, S., & Pradeep, A. R. (2018). Comparative evaluation of subgingivally-delivered 1% metformin and Aloe vera gel in the treatment of intrabony defects in chronic periodontitis patients: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Journal of Investigative and Clinical Dentistry, 9(3), e12324.

Ipshita, S., Kurian, I. G., Dileep, P., Kumar, S., Singh, P., & Pradeep, A. R. (2018). One percent alendronate and aloe vera gel local host modulating agents in chronic periodontitis patients with class II furcation defects: A randomized, controlled clinical trial. Journal of Investigative and Clinical Dentistry, 9(3), e12334.

Ashouri Moghaddam, A., Radafshar, G., Jahandideh, Y., & Kakaei, N. (2017). Clinical evaluation of effects of local application of Aloe vera gel as an adjunct to scaling and root planning in patients with chronic periodontitis. Journal of Dentistry (Shiraz), 18(3), 165–172.

Azadmehr, A., Afshari, A., Baradaran, B., Hajiaghaee, R., Rezazadeh, S., & Monsef-Esfahani, H. (2009). Suppression of nitric oxide production in activated murine peritoneal macrophages in vitro and ex vivo by Scrophularia striata ethanolic extract. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 124(1), 166–169.

Jeong, E. J., Ma, C. J., Lee, K. Y., Kim, S. H., Sung, S. H., & Kim, Y. C. (2009). KD-501, a standardized extract of Scrophularia buergeriana has both cognitive-enhancing and antioxidant activities in mice given scopolamine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 121(1), 98–105.

Kerdar, T., Rabienejad, N., Alikhani, Y., Moradkhani, S., & Dastan, D. (2019). Clinical, in vitro and phytochemical, studies of Scrophularia striata mouthwash on chronic periodontitis disease. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 239, 111872.

Baranowska, M., & Bartoszek, A. (2016). Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of bioactive phytochemicals from cranberry. Postepy Higieny I Medycyny Doswiadczalnej (Online), 70, 1460–1468.

Duncan, D. (2019). Alternative to antibiotics for managing asymptomatic and non-symptomatic bacteriuria in older persons: A review. British Journal of Community Nursing, 24(3), 116–119.

Wawrysiuk, S., Naber, K., Rechberger, T., & Miotla, P. (2019). Prevention and treatment of uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections in the era of increasing antimicrobial resistance—non-antibiotic approaches: A systemic review. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 300(4), 821–828.

Feghali, K., Feldman, M., La, V. D., Santos, J., & Grenier, D. (2011). Cranberry proanthocyanidins: Natural weapons against periodontal diseases. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 60(23), 5728–5735.

Ben Lagha, A., Howell, A., & Grenier, D. (2019). Cranberry Proanthocyanidins Neutralize the Effects of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans Leukotoxin. Toxins, 11(11), 662.

Rajeshwari, H., Dhamecha, D., Jagwani, S., Patil, D., Hegde, S., Potdar, R., et al. (2017). Formulation of thermoreversible gel of cranberry juice concentrate: Evaluation, biocompatibility studies and its antimicrobial activity against periodontal pathogens. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 75, 1506–1514.

de Medeiros, A. K. B., de Melo, L. A., Alves, R. A. H., Barbosa, G. A. S., de Lima, K. C., & Carreiro, A. F. P. (2016). Inhibitory effect of cranberry extract on periodontopathogenic biofilm: An integrative review. Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology, 20(5), 503.

Ben Lagha, A., Sp, D., Desjardins, Y., & Grenier, D. (2015). Wild blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium Ait.) polyphenols target Fusobacterium nucleatum and the host inflammatory response: Potential innovative molecules for treating periodontal diseases. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 63(31), 6999–7008.

Tipton, D., Hatten, A., Babu, J., & Dabbous, M. K. (2016). Effect of glycated albumin and cranberry components on interleukin-6 and matrix metalloproteinase-3 production by human gingival fibroblasts. Journal of Periodontal Research, 51(2), 228–236.

Bedran, T. B. L., Spolidorio, D. P., & Grenier, D. (2015). Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate and cranberry proanthocyanidins act in synergy with cathelicidin (LL-37) to reduce the LPS-induced inflammatory response in a three-dimensional co-culture model of gingival epithelial cells and fibroblasts. Archives of Oral Biology, 60(6), 845–853.

Tipton, D., Carter, T., & Dabbous, M. K. (2014). Inhibition of interleukin 1β–stimulated interleukin-6 production by cranberry components in human gingival epithelial cells: Effects on nuclear factor κB and activator protein 1 activation pathways. Journal of Periodontal Research, 49(4), 437–447.

Tipton, D., Cho, S., Zacharia, N., & Dabbous, M. (2013). Inhibition of interleukin-17-stimulated interleukin-6 and-8 production by cranberry components in human gingival fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Journal of Periodontal Research, 48(5), 638–646.

Zare Javid, A., Maghsoumi-Norouzabad, L., Ashrafzadeh, E., Yousefimanesh, H. A., Zakerkish, M., Ahmadi Angali, K., et al. (2018). Impact of cranberry juice enriched with omega-3 fatty acids adjunct with nonsurgical periodontal treatment on metabolic control and periodontal status in type 2 patients with diabetes with periodontal disease. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 37(1), 71–79.

Penolazzi, L., Lampronti, I., Borgatti, M., Khan, M. T. H., Zennaro, M., Piva, R., et al. (2008). Induction of apoptosis of human primary osteoclasts treated with extracts from the medicinal plant Emblica officinalis. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 8(1), 59.

Kaur, P., Makanjuola, V. O., Arora, R., Singh, B., & Arora, S. (2017). Immunopotentiating significance of conventionally used plant adaptogens as modulators in biochemical and molecular signalling pathways in cell mediated processes. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 95, 1815–1829.

Yokozawa, T., Kim, H. Y., Kim, H. J., Okubo, T., Chu, D.-C., & Juneja, L. R. (2007). Amla (Emblica officinalis Gaertn.) prevents dyslipidaemia and oxidative stress in the ageing process. British Journal of Nutrition, 97(6), 1187–1195.

KL Shanbhag, V. (2015). Triphala in prevention of dental caries and as an antimicrobial in oral cavity-A review. Infectious Disorders-Drug Targets (Formerly Current Drug Targets-Infectious Disorders), 15(2), 89–97.

Kumar, A., Tantry, B. A., Rahiman, S., & Gupta, U. (2011). Comparative study of antimicrobial activity and phytochemical analysis of methanolic and aqueous extracts of the fruit of Emblica officinalis against pathogenic bacteria. Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 31(3), 246–250.

Grover, S., Tewari, S., Sharma, R. K., Singh, G., Yadav, A., & Naula, S. C. (2016). Effect of subgingivally delivered 10% emblica officinalis gel as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis–A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytotherapy Research, 30(6), 956–962.

Tewari, S., Grover, S., Sharma, R. K., Singh, G., & Sharma, A. (2018). Emblica officinalis irrigation as an adjunct to scaling and root planing: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Dentistry Indonesia, 25(1), 4.

Amarasena, N., Ogawa, H., Yoshihara, A., Hanada, N., & Miyazaki, H. (2005). Serum vitamin C–periodontal relationship in community-dwelling elderly Japanese. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 32(1), 93–97.

Tada A, Miura H (2019) Relationship between vitamin C and periodontal diseases: A systematic review.

Varela-López, A., Navarro-Hortal, M., Giampieri, F., Bullón, P., Battino, M., & Quiles, J. (2018). Nutraceuticals in periodontal health: A Systematic review on the role of Vitamins in periodontal health maintenance. Molecules, 23(5), 1226.

Staudte, H., Sigusch, B., & Glockmann, E. (2005). Grapefruit consumption improves vitamin C status in periodontitis patients. British Dental Journal, 199(4), 213.

Dodington, D. W., Fritz, P. C., Sullivan, P. J., & Ward, W. E. (2015). Higher intakes of fruits and vegetables, β-carotene, vitamin C, α-tocopherol, EPA, and DHA are positively associated with periodontal healing after nonsurgical periodontal therapy in nonsmokers but not in smokers. The Journal of Nutrition, 145(11), 2512–2519.

Woelber, J. P., & Tennert, C. (2020). Diet and periodontal diseases. In The impact of nutrition and diet on oral health (Vol. 28, pp. 125–133). Karger Publishers.

Graziani, F., Discepoli, N., Gennai, S., Karapetsa, D., Nisi, M., Bianchi, L., et al. (2018). The effect of twice daily kiwifruit consumption on periodontal and systemic conditions before and after treatment: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Periodontology, 89(3), 285–293.

Javid, A. Z., Hormoznejad, R., allah Yousefimanesh, H., Haghighi-zadeh, M. H., & Zakerkish, M. (2019). Impact of resveratrol supplementation on inflammatory, antioxidant, and periodontal markers in type 2 diabetic patients with chronic periodontitis. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 13(4), 2769–2774.

Abdelmonem, H. M., Khashaba, O. H., Al-Daker, M. A., & Moustafa, M. D. (2014). Effects of aloe vera gel as an adjunctive therapy in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A clinical and microbiologic study. Mansoura J Dent, 1(3), 11–119.

Deepu, S., Kumar, K. A., & Nayar, B. R. (2018). Efficacy of Aloe vera Gel as an Adjunct to Scaling and Root Planing in Management of Chronic localized Moderate Periodontitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. International Journal of Oral Care and Research, 6(2), S49–S53.

Pradeep, A., Garg, V., Raju, A., & Singh, P. (2016). Adjunctive local delivery of Aloe vera gel in type 2 diabetics with chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Periodontology, 87(3), 268–274.

Agrawal, C., Parikh, H., Virda, R., Duseja, S., Shah, M., & Shah, K. (2019). Effects of aloe vera gel as an adjunctive therapy in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. World Journal of Advanced Scientific Research, 2(1), 154–168.

Sahgal, A., Chaturvedi, S. S., Bagde, H., Agrawal, P., Suruna, R., & Limaye, M. (2015). A randomized control trial to evaluate efficacy of anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory effect of aloevera, pomegranate and chlorhexidine gel against periodontopathogens. Journal of International Oral Health, 7(11), 33–36.

Virdi, H. K., Jain, S., & Sharma, S. (2012). Effect of locally delivered aloe vera gel as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A clinical study. Indian Journal of Oral Sciences, 3(2), 84.

Singh, H. P., Sathish, G., Babu, K. N., Vinod, K., & Rao, H. P. (2016). Comparative study to evaluate the effectiveness of Aloe vera and metronidazole in adjunct to scaling and root planing in periodontitis patients. Journal of International Oral Health, 8(3), 374.

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fakheran, O., Khademi, A., Bagherniya, M., Sathyapalan, T., Sahebkar, A. (2021). The Effects of Nutraceuticals and Bioactive Natural Compounds on Chronic Periodontitis: A Clinical Review. In: Sahebkar, A., Sathyapalan, T. (eds) Natural Products and Human Diseases. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology(), vol 1328. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73234-9_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-73234-9_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-73233-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-73234-9

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)