Abstract

This study is designed to investigate the effects of capital equity fund accessibility and the development of microenterprise training programmes on micro-entrepreneurship, economic vulnerability, and household income among members of Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM). This research adopted a cross-sectional study design and collected data through questionnaires and structured interviews. The participants were 523 impoverished families and low-income households in Peninsular Malaysia who were selected based on the information provided by AIM. Multiple regression analysis was used to analyse the collected data. The outcomes of this study presented some concrete evidence that access to the working capital generated a positive impact on low-income households and decreased the economic vulnerability among low-income urban and rural members of AIM. Furthermore, it was also found that the elongation of the participation period had a negative impact on microenterprise income and lowered the economic vulnerability level among the urban participants but displayed an opposite effect among the rural participants. In contrast, economic loan received had a positive impact on urban participants but negatively impacted the microenterprise income of rural participants. This study has extended the assets and financial approach of the neoclassical theory and also the understanding of low-income communities by offering some policy development to increase poverty eradication among the urban and rural low-income members of AIM in an emerging economy.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

1.1 Overview of Microcredit in Malaysia

A fundamental economic challenge in various countries that has been discussed in relation to disproportionate income and vulnerability is poverty. In developing countries, poverty is an important concern affecting economic development, particularly in urban and rural areas. Both these areas experience a high level of material poverty, affecting the wellbeing of the residents there (Al-Mamun et al. 2018). Thus, to enhance the economic wellbeing and eradicate poverty, income disparities must be reduced and income-generating activities must be created, which will lead to an increase in the household income, consumption level, and assets holding (Baye 2013; Khan 2014). According to Olateju (2016), poverty is multidimensional and influenced by the norms, culture, and practices of the communities. The World Bank (2018) has reported that approximately 2.4 billion people live in a pitiful condition with an income of less than US$ 1.90 daily. Notably, low-income families have been unable to allocate their finances to education and income-generating activities due to restricted access to financial support (Mustapa et al. 2018). Therefore, both financial and non-financial assistances are equally important in reducing poverty. Poverty is defined as a financial deficiency to gain fundamental necessities, including nutriment and non-nutriment sector (Economic Planning Unit 2002). The government of Malaysia has established a standard, poverty line income (PLI), to measure poverty. Based on the PLI, households in Peninsular Malaysia with monthly gross revenue of RM 460 are classified as poor (DSM 2017). The Malaysian government has succeeded in poverty alleviation, reducing the number of families who live below the PLI standard from 50% to less than 1% in 2014. Nonetheless, poverty still exists and remains a primary issue in rural and urban areas (Siwar et al. 2016). Thus, the government needs to pay serious attention to highlighting the issues of income allocation and poverty (Nair and Sagaran 2015). Economic vulnerability plays a crucial role as a poverty-diminishing element and reveals the susceptibility to poverty in the future (Feeny and McDonald 2015). Thus, it can be defined as the probability to experience poverty, with the chances to encounter shocks of poverty. In Malaysia, households and microenterprises confront vulnerabilities in multiple settings including economic, social and surrounding reduced incident and intolerable poverty (Al-Mamun and Mazumder 2015). The most crucial risks among low-income households in Malaysia, as well as in other developing countries are the inequality in income allocation and socioeconomic vulnerabilities (Nair and Sagaran 2015).

The government of Malaysia has a microfinancing sector, which is a formal scheme designed to increase the borrowers’ (low-income households) wellbeing by making it easier for them to access loans, savings, and other services (Schreiner 2000). This sector enables the clients to gain financial assistance and social services to empower their wellbeing that refers to their household and micro or small enterprise’s performance (Al-Shami et al. 2013). Microfinance exploits group-lending techniques, which provide financial working capital and social capital by improving the trust, interaction, and cooperation among clients for them to form memberships, networks and social mobilities (Al-Mamun 2014). Microfinance institutions (MFIs) provide a wide range of opportunities to overcome poverty, inequity in income distribution, and economic vulnerability via microcredit and training programmes to eligible clients (Al-Mamun 2014; Ikenwilo et al. 2016). This has demonstrated MIFs as an effective and efficient financial tool for combating poverty (Ariful et al. 2017), by creating jobs including self-employment and increasing the households’ income (Chhay 2011), improving the wellbeing of poor households and microenterprises (Waheed 2009), ameliorating women’s socioeconomic condition and empowerment (Samer et al. 2017), and enhancing the socioeconomic condition of the borrowers (Al-Mamun et al. 2014). Therefore, MFIs are recognised as a vital socioeconomic and financial instrument in rural and urban areas through the creation of income-generating opportunities and small businesses that reduce unemployment and eradicate poverty (Ariful et al. 2017; Tammili et al. 2018).

Internationally, microcredit is an essential financial instrument used to combat poverty and boost the socioeconomic wellbeing of low-income communities (Nader 2008; Ahmad et al. 2011; Noor Raihani et al. 2018). Both rural and urban households gain benefits by joining income-earning activities such as acquiring small loans and training to improve their competences via microcredit. In Malaysia, it has been proven that microcredit can generate progress in terms of socioeconomic development among low-income households and microenterprises. Based on past studies on economic effect, it was shown that microcredit improved microenterprises’ performance (Dzisi and Obeng 2013), increased microenterprises’ income, growth, and net worth of assets (Mustapa et al. 2019), greatly altered the household income level and personal asset acquirement among borrowers (Al-Shami et al. 2017a, b), decreased the level of economic vulnerability (Al-Mamun and Mazumder 2015), reduced unemployment (Khan 2014), elevated women’s status and their economic condition in the family and community (Chhay 2011), increased self-confidence and self-economic strength among women (Nader 2008), and ultimately, lowered the poverty rate (Ariful et al. 2017). In addition, microcredit has not only managed to create more employment opportunities at both the community and household levels, but it has also positively influenced the borrowers’ quality of life (Al-Mamun et al. 2011), assisted in developing the rural enterprises’ expansion, skills, confidence enhancement, and social positioning among the rural people (Chan and Abdul Ghani 2011), developed the formal bonding social capital (Al-Mamun 2014), improved gender equality and strengthened the women’s role in household decision-making and economic advantage in terms of economic resources (Al-Shami et al. 2017a, b). However, the impact of microcredit on economic wellbeing is still vague and it varies (Angelucci et al. 2013; Al-Shami et al. 2015) between the rural and urban areas (Baye 2013; Bhuiyan and Ivlevs 2018; Jain and Muñoz 2017), besides in the methodological approach used (Ikenwilo et al. 2016; Islam 2014). Angelucci et al. (2013) have indicated that there is no connection between access to microcredit and profit. Furthermore, household income and consumption have not affected the economic wellbeing. Meanwhile, Ganlea et al. (2015) found that microcredit harms rural women’s prosperity because of harassment and abuse, indebtedness, and the inability to repay loans. Omorodion (2007) has proclaimed that microcredit programmes are not improving poverty among rural women. On the other hand, Rooyen (2012) corroborated the effects of microcredit and micro-savings on impecunious families, which consisted of income, savings, expenditure, and accumulation of assets as well as non-financial outcomes including health, nutrition, food security, education, child labour, women’s empowerment, housing, job creation, and social cohesion. This confirmed that there are various impacts on the economic wellbeing of poor households. Some studies have found different findings between rural and urban areas concerning the influence of microcredit on economic wellbeing. For example, Baye (2013) indicated that access to credit in rural areas was more effective in augmenting the households’ economic wellbeing than credit access in urban areas. Likewise, Jain and Muñoz (2017) have divulged that rural borrowers are showing better progress in reducing poverty over time compared to urban ones, based on three Asian Microfinance Institutions (AMI). In contrast, Bhuiyan and Ivlevs (2018) showed that microcredit borrowing had an indirect negative effect on the entrepreneurs’ overall life satisfaction, consequently, decreasing their economic wellbeing in rural areas. Even though many studies on the impact of microcredit programmes on the economic wellbeing of participants have been conducted, not much evidence is available in the literature for participants in both rural and urban areas. Therefore, this study brings new evidence to analyse the effects of capital equity fund accessibility and the development of microenterprise training programmes on micro-entrepreneurship, economic vulnerability, and household income among members of Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM) in both rural and urban areas.

1.2 Overview of Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM)

AIM was established in 1987 in the state of Selangor as a non-governmental organisation (NGO) with the social mission of focusing on poor and low-income households (Samer et al. 2015). This NGO, which concentrates on the development of the socioeconomic needs of low-income households, is one of the leading organisations in Malaysia (Al-Mamun and Mazumder 2015). AIM’s loans are non-interest and based on Islamic principles with 10% operational and management fees including 2% as compulsory saving. Poor households receive assistance from AIM, which provides collateral-free small-scale financial services and skill-building training. AIM’s loan operation is based on the Grameen bank model of group-lending, in which a group of five women are given the loan and they settle the repayment through share joint liability (Al-Shami et al. 2017a, b). The selection of the groups is based on the clients’ average monthly household income. Families with an average monthly household income that is below the PLI are eligible to apply for a microcredit loan from AIM as they are categorised under the impoverished group. AIM used to focus only on households in rural areas with an income below the PLI standard. However, AIM has extended its programme’s services to urban areas since the middle of 2008. For urban areas, the benchmark for a household to be accepted into the programme is an average monthly income of below RM 2000 (AIM 2010). AIM prioritises the loan purpose differently for urban and rural areas. Specifically, income-generating activities are prioritised for urban areas, whereas economic loans, recovery loans, education loans, and housing loans are offered for rural areas (Al-Mamun and Mazumder 2015).

The principal objectives of AIM are to combat and eradicate poverty and economic vulnerability among poor and low-income households in both rural and urban areas (Hassan and Ibrahim 2015). AIM provides funding for income-generating activities, guidance, and training to entrepreneurs from poor and low-income communities (Al-Mamun et al. 2014; Terano et al. 2015; Tammili et al. 2018; Al-Shami et al. 2017a, b). Other than that, AIM also prioritises in providing financial services, guidance, and on-going training to entrepreneurs and microentrepreneurs (Hassan and Ibrahim 2015). Moreover, this NGO also delivers training development, including basic accounting knowledge, the necessary entrepreneurship skills, ways to successfully manage finance, communication in business, and borrowers’ development activities and programmes. These training programmes improve households and microenterprises’ management skills and enable the generation of income and creation of employment opportunities (Al-Mamun et al. 2014). The microcredit programmes increase small businesses’ revenue, improve the economic wellbeing, and raise the standards of living (Tammili et al. 2018). Financing activities of the households and microenterprises increase their income and economic wellbeing. Besides, financial vulnerability and deprivation of formal financial services among women have led AIM to target loans and other financial services for them. AIM believes women are the backbone of households and society and thus has chosen them as the target group for the microcredit services (Al-Shami et al. 2017a, b).

2 Literature Review

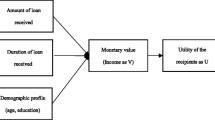

2.1 The Founding of the Theory

This study has developed the theory based on the neoclassical theory that emphasises the role of inequivalent funding of talents, skills, and capital influences on individuals’ productivity in causing poverty within a market based competitive economic system (Marshall 1984). According to the monetary approach, a neoclassical declared that impoverished households are facing a higher risk to become poor when they are hit by a negative income shock, thus, becoming more vulnerable to wellbeing shocks and it is the crucial factor that leads to poverty (David and Martinez 2014). Ulimwengu (2008) has opined that a non-existent credit and insurance market or risk related to the depletion of self-financing in physical, human, and social capital will result in individual or household poverty. Furthermore, Wood (2003) affirmed that fundamental security deprivation reflects poverty that is prevalent both over time and across multiple aspects of living conditions. The effort to assist the poor attain wellbeing comes hand in hand with a strategy that stresses on developing the improving system within the community including creating and developing alternative institutions which have access, openness, innovation, and a willingness, besides focusing on catering to alternative business and housing programmes (Bradshaw 2006).

2.2 Impact of Development Initiatives

Development initiatives’ primary mission is to provide funded and non-funded assistance to low-income communities to increase their income and decrease their economic vulnerability to prevent poverty. To achieve this mission, multilateral institutions such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and NGOs along with governments are working together to better assist low-income households and microenterprises to end their economic vulnerability and to alleviate their income and economic wellbeing. In Malaysia, organisations like AIM, TEKUN and LKIM administer income-generating activities through the development of enterprise training programmes for low-income households and microenterprises (Anderson and Laura 2002). In addition, poverty eradication programmes approved by the government (Bilan 2009) are broken down into several main areas such as business environment, loan eligibility, legal and regulatory environmental finance, direct finance, and loan guarantees.

2.3 Impact on Microenterprise Income

Mustapa et al. (2019) suggested that funding microentrepreneurs for job creation and income-generating activities are advantageous for poverty alleviation and economic wellbeing improvement during pre- and post-participation in microcredit and training programmes. Moreover, Dunn and Arbuckle (2011) added that enterprises, which received microcredit, experienced a positive effect from the microcredit programmes by showing better performance in terms of income, fixed asset, and employment compared to enterprises that did not receive financial assistance. Similarly, Tammili et al. (2018) have shown that AIM programmes positively affected microenterprises’ income after joining different microcredit programmes. Alam et al. (2015) indicated that AIM’s microcredit programmes enhanced microenterprises and households’ income and wellbeing. Nevertheless, involvement in microcredit programmes did not provide additional skills and knowledge to the targeted group as claimed by numerous borrowers. Mustapa et al. (2019) have analysed the conflicting effects on the psychological aspect of entrepreneurs based on credit availability and long-term loans. On the other hand, three microfinances from Bangladesh namely BRAC, ASA, and PROSHIKA had positively and significantly affected the poverty alleviation index and as a result, improved microentrepreneurs’ level of income (Khanam et al. 2018). However, Peprah (2012) has suggested that the wellbeing score can be low since the principal challenge of microfinance is to help low-income people to become economically independent. Corresponding to Olateju’s (2016) findings, microenterprise owners’ economic wellbeing is more significantly impacted by participating in microcredit programmes than the non-participants. Hence, the following hypothesis was developed:

Hypothesis 1: Access to working capital and enterprise development training programmes of Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM) increased the income of microenterprises in the urban and rural areas.

2.4 Impact on Household Income

Preceding studies have proved that a household’s income, i.e. the average monthly income of all the members of the household such as wage income, net income from a business, livestock and agricultural activities, rental income, investment income, and gifts earned, has increased through the essential role of microcredit and training programmes (Mustapa et al. 2018). A household’s income is assumed to increase through income-generating activities via the development initiatives that provide microcredit and training programmes in a base-scale of loan (Mustapa et al. 2018). Furthermore, previous research examined the influence of microcredit programmes on household’s income and a significant effect was demonstrated on the generation of new income, women’s socioeconomic well-being, and poverty reduction (Ahmad et al. 2011; Ariful et al. 2017). Badri (2013) has provided evidence of increment in the economic wellbeing of families through the increase in income, better food consumption, support for the education of children, and improvement of home furnishing with positively and significantly to household financial-economic and well-being (Baye 2013) along with crucial contributions of micro-credit programs. In addition, Jain and Muñoz (2017) have explored the effect of microcredit on the poverty level of rural and urban borrowers of three AMIs and concluded that it is generally an effective strategy for MFIs seeking a higher social return on investments by targeting disadvantaged rural people. Also, Khan (2014) has indicated that microfinance has shown a positive impact on household income and consumption. Nonetheless, other studies have reported that microcredit leads to a decrease in the economic wellbeing, whereby there is no relation between its programmes and household income (Ganlea, Afriyie, and Segbefia 2015; Omorodion 2007; Rooyen 2012). Based on past studies, the following hypothesis was developed:

Hypothesis 2: Access to working capital and enterprise development training programmes of Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM) increased the income of households in urban and rural areas.

2.5 Impact on Economic Vulnerability

Mustapa et al. (2018) have defined economic vulnerability as a risk of exposure to potential harmful events in the future and become an economical challenge for developing countries. Economic vulnerability factors are income poverty, asset poverty, and risk exposure to political, natural, and economic uncertainties. Al-Mamun et al. (2014) stated that economic vulnerability among low-income households can be minimised via access to both microcredit and training programmes. These researchers reported that participants of AIM’s microcredit programme had decreased economic vulnerability. Similarly, Al-Mamun and Mazumder (2015) found that participants of AIM’s microcredit programme displayed an increment in their household income, while the poverty rate and level of economic vulnerability had gradually reduced. However, Islam (2014) has discovered that having access to microcredit leads to an increase in susceptibility to poverty, particularly for hard-core poor households and concluded that there is a lack of evidence that microcredit contributes towards reducing poverty. Ikenwilo et al. (2016) have claimed that there is a positive outcome of microcredit programmes toward women’s vulnerability and empowerment in the city areas and have shown that women beneficiaries are significantly less vulnerable and more empowered than non-beneficiaries. Moreover, the social capital of the recipients is increased through the improved ability to network and undertake community activities, besides improved economic wellbeing. Recently, Mustapa et al. (2018) concluded that the duration of participating in the programme, economic loan received, and proportion of hours spent on training programmes positively impacted the household income to decrease economic vulnerability. Based on this evidence, the following hypothesis was developed.

Hypothesis 3: Access to working capital and enterprise development training programmes of Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM) decreased the economic vulnerability of participants in urban and rural areas.

3 Research Methodology

A questionnaire and structured interview were used to investigate the effects of working capital accessibility and the development of microenterprise training programmes on AIM members’ microenterprise income, household income, and economic vulnerability. The questionnaire had been designed by using unbiased terms to ensure the precise answers are provided based on respondent’s context. The questions were adopted from Man et al.’s (2008) with minor modifications. The sample of this study was poor and low-income households in Malaysia. To obtain the list of poor and low-income households, this study approached AIM, a development organisation funded by the Malaysian government. AIM has delivered financial assistance and training programmes to improve the socioeconomic status of nearly 380,000 poor and low-income households (AIM 2018). From a total of 134 branches in Malaysia, this study selected 15 AIM branches, i.e. three from Selangor, Seremban (Negeri Sembilan), Melaka, Johor Bahru (Johor), Kuantan (Pahang), Machang and Tumpat (Kelantan), Besut (Terengganu), Perlis, Batang Padang (Perak), and Alor Star, Baling and Pendang (Kedah). The sample was chosen during the weekly centre meetings. The selected respondents were engaged with the interview sessions based on the question given so that they can easily responses in similar cathegories. Data were derived from 523 poor households with a low-income in Peninsular Malaysia.

3.1 Sample Size

The sampling frame of this study was based on the latest report of AIM (AIM, 2018). According to this report, the total number of poor households was 380,000. Therefore, according to Krejcie and Morgan (1970), the sample size for collecting data was 384, i.e. at least 384 participants were needed for this study. Nevertheless, this study collected data from 523 poor households with a low-income in Peninsular Malaysia, which was higher than the minimum sample size required. Krejcie and Morgan (1970) have developed a well-established scientific table, which determines research population and its corresponding sample size applicable for scientific research.

Where.

S = required sample size.

X2 = the table value of chi-square for 1 degree of freedom at the desired confidence level (3.841).

N = the population size (380000).

P = the population proportion (assumed to be 0.50).

d2 = the degree of accuracy expressed as a proportion (0.05).

3.2 Dependent Variable

This study measured the effect of microcredit programmes on microenterprise income, household income, and economic vulnerability among AIM members. The average monthly income was the post-participation average monthly income (of the last 12 months) minus the pre-participation average monthly income (of the previous 12 months). The average monthly income was the combined income of all the members in the household. Since participants from different development organisations with varying household income requirements were included, the study’s main aim was to look in-depth into the effect of development programmes participation on the changes in current household income and household income before participation. The vulnerability can be conceptualised as vulnerability to income poverty, asset poverty, and risk exposure to political turmoil, natural disasters, and economic instability. It is measured by using the index below:

EV = Vulnerability index (measures the level of economic vulnerability).

CVi = Coefficient of variation of average monthly household income.

ASTA = \(\sqrt{\stackrel{\ldots}{\mathrm{A}}/\mathrm{Ai}}\)

DIVsi = Determines the fraction of total income from enterprise income,

POVi = \(\sqrt{PLI}\) PH /IHH.

IHH refers to the average monthly household income.

PLIPH reflects the income of bottom 40% of the Malaysian population.

DIVi = \(\sqrt{\mathrm{SOI}}\)

The total number of income sources.

DEPh = Households with higher fraction of dependent members per gainfully employed member ratio are presumed to appear more vulnerable.

3.3 Control Variable

Gender, education, age, marital status, and location were expected to affect microenterprise income, household income, and economic vulnerability. For instance, concerning the education variable in this study, the assumption was that participants with a high education level would be less vulnerable. Referring to gender, female-headed households would be more vulnerable to poverty and gain less income compared to male-headed households. As for marital status, it was assumed that married households would be more exposed to challenges in contrast to divorced, widowed, and separated households, corresponding to the economic level achievement. Next, older households would possess a better financial status and be less vulnerable to poverty compared to younger households. In terms of location, rural households were expected to be less vulnerable to poverty compared to urban households. For the selected variables, this study assigned a value of 1 for males and 0 for females, and 1 for married and 0 for single, separated, divorced, and widowed.

4 Findings Summary

4.1 Demographic Characteristics

Data were collected from 523 low-income households in Selangor, Melaka, Johor, Pahang, Kelantan, Terengganu, Perlis, Perak, and Kedah. Most of the respondents (98.5%) were females. In terms of the marital status, 442 of the respondents (84.5%) were married, followed by widowed 50 (9.6%), single (3.3%), and separated (2.7%). Concerning the employment status, most of the households, i.e. 487 (93.1) had gainful employment. The remaining respondents were categorised under domestic work only (4.8%), unemployed (0.8%), unable to work (0.8%), and working for food (0.3%). Most of the households resided in a rural area (53.7%) while the rest in an urban area (46.3%) (Table 1).

4.2 Descriptive Statistics

This part highlight the respondents’ feedback obtained from data collected through the questionnaires. Accordingly, Table 2 presents the mean value of the number of months of participation or the length of participation, i.e. 58.46 with a standard deviation (SD) of 64.15. The mean value of the economic loan received was RM 12,321.03 with an SD of RM 19,776.62. Furthermore, the mean age of the participants was 43.64 years, with an SD of 10.95 years, while the mean number of years in school was 4.84 years, with an SD of 4.73 years. Next, the mean number of gainfully employed members was 2.77, with an SD of 1.69 and the mean value of the household head’s number of years in school was 4.52 years with an SD of 5.05 years. Besides, the mean value of the source of income was 2.57 with an SD of 1.61, whereas the mean value of the proportion of loan invested in income-generating activities was 32.37 with an SD of 42.72. The mean value for average monthly microenterprise income was RM 1,498.68 with an SD of RM 1,598.32, while for household income it was RM 2,299.69 with an SD of RM 1,858.16. Finally, the mean value for economic vulnerability was 0.96 with an SD of 1.29.

4.3 Partial Correlation

A partial correlation was conducted to determine the change after participation in household income, microenterprise income, economic vulnerability, and economic loan received. The findings in Table 3 shows that the economic loan received has a positive and statistically significant correlation with the average monthly household income after controlling the effect of clients’ age, education (number of years in school), number of gainfully employed members, household head’s number of years in school, source of income, and proportion of loan invested in income-generating activities. Next, the findings revealed a positive significant correlation between the number of months of participation and the economic loan received. Furthermore, there was also a positive significant correlation between the number of months of participation and the average monthly microenterprise income and average monthly household income. Finally, it was demonstrated that the change in economic vulnerability negatively correlated with the number of months of participation (β = –0.065 and p-value = 0.069), the economic loan received (β = –0.034 and p-value = 0.220), the average monthly microenterprise income (β = –0.049 and significant value = 0.133), and the average monthly household income (β = –0.242 and significant value = 0.000) after controlling the effect of clients’ age, education (number of years in school), number of gainfully employed members, household head’s number of years in school, source of income, and proportion of loan invested in income-generating activities.

4.4 Impact on Micro-enterprise Income

The r2 value for microenterprise income was 0.046, expressing that 4.60% of the variation in changes in household income after participation in the programme was explained by the number of months of participation, economic loan received, average monthly microenterprise income, average monthly household income, economic vulnerability, gender, age, education, number of gainfully employed members, household head’s number of years in school, source of income, and proportion of loan invested in income-generating activities. Based on unstandardized residual value, the stem and leaf plot indicated outliers. Thus, the outliers were removed and the data were reanalysed using 298 respondents, whereby the p-value for Kolmogorov-Smirnov of normality (n = 298) was 0.092; therefore, the data were normal with the Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) value below 5.

The results in Table 4 demonstrate that the number of months of participation in the development initiatives has a positive effect (N = 523 and N = 298) on the changes of past-participation microenterprise income only after the removal of the outliers (N = 298). Moreover, the economic loan received positively and significantly affected the changes in microenterprise income. The impact of the number of years in school, number of gainfully employed members, household head’s number of years in school, source of income, and proportion of loan invested in income-generating activities had a positive and significant effect on the changes in microenterprise income. In contrast, the variable age had a positive and insignificant effect on microenterprise income.

4.5 Impact on Household Income

The r2 value for household income was 0.039, which indicated that 3.90% of the variation in changes in household income after participation in the programme was explained by the number of months of participation, economic loan received, average monthly microenterprise income, average monthly household income, economic vulnerability, gender, age, education, number of gainfully employed members, household head’s number of years in school, source of income, and proportion of loan invested in income-generating activities. After removing the outliers and reanalysing the data of the remaining 213 respondents, the p-value for Kolmogorov-Smirnov of normality (n = 213) was 0.200, r2 = 0.394, F (Sig) = 0.000, which indicated a normal data and no multicollinearity was identified in this study. The findings revealed that the number of months of participation in the development initiatives positively affected the changes in household income only after the outliers were removed (N = 523 and N = 213). Besides, the economic loan received had a positive and significant effect on changes in household income. Similarly, the number of years in school and the proportion of loan invested in income-generating activities had a significantly positive effect on the changes in household income. Nonetheless, the number of gainfully employed members, the household head’s number of years in school, and source of income had a positive but insignificant effect on household income. In terms of the control variable, age had a negative effect on the changes in household income (Table 5).

4.6 Impact on Economic Vulnerability

For economic vulnerability, the r2 value was 0.057, which indicated that 5.70% of the variation in economic vulnerability was represented by the number of months of participation, economic loan received, average monthly microenterprise income, average monthly household income, economic vulnerability, gender, age, education, number of gainfully employed members, household head’s number of years in school, source of income, and proportion of loan invested in income-generating activities. After removing the outliers, with the remaining 168 respondents, the p-value for Kolmogorov-Smirnov increased to 0.063 of normality (n = 168), r2 = 0.220, F (Sig) = 0.000; thus, the data of this study were normal. However, multicollinearity was present, as shown by the VIF value that was under 5.

The findings in Table 6 reveal that the number of months of participation has a reversed and significant effect on economic vulnerability among low-income respondents in the second model (N = 168). However, in the first model, it was not substantial. As such, economic vulnerability decreased with the duration of participation. Consequently, the number of months of participation in enterprise development training reduced economic vulnerability. For economic loan received and source of income, the effect on economic vulnerability in the second model was significantly negative. In contrast to the second model, the first model positively affected economic vulnerability. This implies that respondents who have applied a larger amount of loan are very vulnerable to poverty. After removing the outliers and the distribution became normal, the second model (N = 168) showed that the economic loan received had a negative effect on economic vulnerability. The number of years in school, number of gainfully employed members, household head’s number of years in school, and proportion of loan invested in income-generating activities had a negative and no significant effect on economic vulnerability. On the other hand, the variable age had a positive and insignificant effect on economic vulnerability.

4.7 Multi-group Analysis

The path coefficient results in Table 7 shows that the number of months of participation coefficient value for microenterprise income is –0.151, with a p-value of 0.024 for urban areas. This indicated that the number of months of participation negatively and significantly affected microenterprise income in urban areas. Next, the coefficient value for the number of months of participation was 0.103, with a significant value of 0.096 for rural areas. This meant that the number of months of participation had a positive and insignificant effect on microenterprise income in rural areas. The coefficient value for the number of months of participation was 0.254 with a significant value of 0.995 for urban-rural areas. Therefore, the number of months of participation positively and insignificantly affected microenterprise income in urban-rural areas. In addition, the coefficient for economic loan received showed a value of β = 0.317 at 0.001 significance level, indicating the positive and significant effect on microenterprise income in urban areas. Inversely, the coefficient for economic loan received showed a negative value (β = –0.011) and had an insignificant effect (p-value = 0.849; > 0.05) in rural areas. Finally, in urban-rural, the coefficient for economic loan received presented a positive value (β = 0.328) at 0.001 significance level. Next, the coefficient for the number of months of participation showed a negative (β = –149) and significant (p-value = 0.025; < 0.05) effect on the household income in urban areas. In contrast, the coefficient for the number of months of participation presented a positive (β = 0.021) and insignificant (p-value = 0.714; > 0.05) effect on the household income in rural areas. In urban-rural areas, the coefficient for the number of months of participation showed a positive (β = 0.170) and insignificant (p-value = 0.975; > 0.05) effect on household income. Furthermore, economic loan received had a value of β = 0.377 at 0.001 significance level, which positively and significantly affected the household income in urban areas. Similarly, the coefficient value for economic loan received in rural areas showed a positive value (β = 0.116) at 0.05 significance level (p = 0.045). Also, in urban-rural areas, the coefficient value for economic loan received presented a positive (β = 0.262) and significant (p-value = 0.007; < 0.05) effect on the household income.

Besides, the coefficient for the number of months of participation demonstrated a positive (β = 0.013) and insignificant (p-value = 0.865; > 0.05) effect on economic vulnerability in urban areas, whereas for rural areas, a negative (β = –0.146) and significant (p-value = 0.007; < 0.05) effect was shown. Additionally, the coefficient for the number of months of participation showed a positive (β = 0.159) and significant (p-value = 0.043; < 0.05) effect on economic vulnerability in urban-rural areas. For economic loan received, the coefficient value was negative (β = –0.089) and insignificant (p-value = 0.191; > 0.05) concerning the effect on economic vulnerability in urban areas. Similarly, the coefficient value for economic loan received presented a negative (β = –0.058) and insignificant (p-value = 0.241; > 0.05) effect on economic vulnerability in rural areas. Nonetheless, in urban-rural areas, the coefficient value for the economic loan received showed a positive (β = 0.031) and insignificant (p-value = 0.650; > 0.05) effect on economic vulnerability.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

This research was conducted to analyse the impact of access to working capital (the number of months of participation and economic loan received) on microenterprise income and household income among urban and rural participants of AIM’s microcredit programmes. The regression results showed that the effect of the number of months of participation on microenterprise income was negative and significant in urban areas and conversely, positive and insignificant in urban-rural areas. Nevertheless, for microenterprise income, economic loan received positively and significantly affected urban and urban-rural areas but negatively and insignificant affected rural areas. In addition, for household income, the number of months of participation negatively and significantly affected urban areas, whereas the effect was positive and insignificant in rural and urban-rural areas. Meanwhile, a positive significant effect on household income was exhibited by economic loan received. Besides, for economic vulnerability, the number of months of participation had a positive and insignificant effect in urban, a negative and significant effect in rural, and a positive and significant effect in urban-rural areas. As such, the number of months of participation among rural participants reduced their economic vulnerability. The effect of economic loan received was negative and insignificant in both urban and rural areas, whereas it was positive and insignificant in urban-rural areas for economic vulnerability. This indicated that economic loan received lowered economic vulnerability among both urban and rural participants through enterprise development programmes.

The key findings have proved that accessibility to working capital and training programmes offered via microcredit have an evident influence on household income and economic vulnerability. Further analysis of economic vulnerability would be an interesting subject matter to not only promotes economic performance but to expose financial crisis and downturns. Moreover, it would be appealing to investigate the role of economic vulnerability to be reduced by initiating investigating ways of low-income household and then relate exposure to risk with other variables. This will be useful information for formulating socioeconomic policies and poverty eradication programmes, particularly for low-income communities in urban and rural areas in Peninsular Malaysia. Therefore, to combat poverty, investigations should expand towards understanding the characteristics of households and microenterprises that are on average, more susceptible to income shocks. Besides, the AIM could potentially provide an effective implication of microcredit by offering flexible access to credit programmes and more training and motivational programmes in the areas of management and marketing support to further improve the entrepreneurial capacities of microenterprises. These training programmes can yield higher microenterprise income and household income and subsequently minimise economic vulnerability among city and village area low-income participants of AIM. Furthermore, it is notably pivotal for the borrowers to be given an appropriate channel for feedback and grievance regarding the performance of MFIs. Moreover, microcredit and training might be stimuli on a small scale and bring positive impacts on the overall standard of living of low-income household participants. For the microenterprise owners operating in the emerging business sector, the focus should be on development initiatives to obtain superior entrepreneurial competencies. Hence, establishing a training centre would provide an environment of continuous support and motivation to frequently participate in training programmes. Nevertheless, this study has a limitation since data were collected from only the AIM and thus, in future research, data can be collected for a longitudinal study and from different MFIs and research areas.

References

Ahmad, F., Siwar, C., Idris, N.A.: Contribution of microcrdit for improving family income of the rural women in Panchagarh District of Bangladesh. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 5(5), 360–366 (2011)

Alam, M., Hassan, S., Said, J.: Performance of Islamic microcredit in perspective of Maqasid Al-Shariah A case study on Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia. Humanomics 31(4), 374–384 (2015)

Al Mamun, A.: Investigating the development and effects of social capital through participation in group-based microcredit programme in Peninsular Malaysia. J. Interdiscip. Econ. 26(1 & 2), 33–59 (2014)

Al- Mamun, A., Abdul Wahab, S., Malarvizhi, C.: Examining the effect of microcredit on employment in Peninsular Malaysia. J. Sustain. Dev. 4(2), 174–183 (2011)

Al-Mamun, A., Mazumder, M.: Impact of microcredit on income, poverty, and economic vulnerability in Peninsular Malaysia. Dev. Pract. 25(3), 333–346 (2015)

Al-Mamun, A., Mazumder, M., Malarvizhi, C.: Measuring the effect of Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia’s microcredit programme on economic vulnerability among hardcore poor households. Progress Dev. Stud. 14(1), 49–59 (2014)

Al-Shami, S.A., Majid, I., Razali, R.M., Rashid, N.: The effect of microcredit on women empowerment in welfare and decisions making in Malaysia. Soc. Indic Res. 137, 1073–1090 (2017a)

Al-Shami, S.A., Majid, I., Razali, M., Rashid, N.: Household welfare and women empowerment through microcredit financing: evidence from Malaysia microcredit. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 27, 894–910 (2017b)

Al-Shami, S.A., Adbul Majid, A., Rashid, N.A., Rizal, M.S.: Conceptual framework: the role of microfinance on the wellbeing of poor people cases studies from Malaysia and Yemen. Asian Soc. Sc. 10(1), 230–242 (2014)

Al-Shami, S.A., Razali, M.M., Majid, I., Rozelan, A., Rashid, N.: The effect of microfinance on women’s empowerment: evidence from Malaysia. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 22(3), 318–337 (2016)

Angelucci, M., Karlan, D., Zinman. J.: Win Some Lose Some? Evidence from a Randomized Microworking Capital Program Placement Experiment by Compartamos Banco (No. w19119). National Bureau of Economic Research, Bonn (2013)

Ariful, C.H., Atanu, D., Ashiqur, R.: The effectiveness of micro-credit programmes focusing on household income, expenditure and savings: evidence from Bangladesh. J. Competitiveness 9(2), 34–44 (2017)

Badri, A.Y.: The Role of Micro-credit System for Empowering Poor Women. Develop. Country Stud. 3(5) (2013)

Baye, M.F.: Household economic well-being: response to micro-credit access in Cameroon. African Dev. Rev. 25(4), 447–467 (2013)

Bradshaw, T.K.: Human and Community Development Department University of California, p. 95616. Davis, CA (2006)

Cuong, N. V., Bigman, D., Berg, M. V., Thieu, V.: Impact of micro-credit on poverty and inequality: the case of the vietnam bank for social policies. Munich Personal RePEc Archive (2007)

Chhay, D.: Women’s economic empowerment through microfinance in Cambodia. Dev. Pract. 21(8), 1122–1137 (2011)

Dauda, R.S.: Poverty and economic growth in Nigeria: Issues and Policies. J. Poverty 21(1), 61–79 (2016)

Davis, E.P., Martinez, M.S.: A review of the economic theories of poverty. National Institute of economic and social research. 435. (2014)

Dunn, E., Arbuckle, J.G.: Microcredit and microenterprise performance: impact evidence from Peru. Small Enterp. Dev. 12(4), 22–31 (2011)

Dzisi, S., Obeng, F. (2013). Microfinance and the Socio-economic wellbeing of women entrepreneurs in Ghana. International Journal of Business and Social Research, 3(11), 45–62

Feeny, S., McDonald, L. (2015): Vulnerability to Multidimensional Poverty: Findings from Households in Melanesia. The Journal of Development Studies,

Ferdousi, F.: Impact of microfinance on sustainable entrepreneurship development. Dev. Stud. Res. 2(1), 51–63 (2015)

Fiala, N.: Access to finance and enterprise growth: evidence from an experiment in Uganda. In: International Labour Office, Employment Policy Department. Employment and Labour Market Policies Branch. ILO, Geneva (2015)

Ganle, J.K., Afriyie, K., Segbefia, A.: Microcredit: empowerment and disempowerment of rural women in Ghana. World Dev. 66, 335–345 (2015)

Goldberg, N.: Poverty eradication through self-employment and livelihoods development: the role of microcredit, variations on traditional microcredit, and alternatives to microcredit. Paper prepared for the United Nations Expert Group Meeting: “Strategies for Eradicating Poverty to Achieve Sustainable Development for All” (2016)

Hassan, M.S., Ibrahim, K.: Sustaining small entrepreneurs through a microcredit program in Penang, Malaysia: a case study. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 25(3), 182–191 (2015)

Idris, A.J., Agbim, K.C.: Micro-credit as a strategy for poverty alleviation among women entrepreneurs in Nasarawa State, Nigeria. J. Bus. Stud. Quart. 6(3) (2015)

Ikenwilo, D., Olajide, D., Obembe, O., Ibeji, N., Akindola, R.: The impact of a rural microcredit scheme targeting women on household vulnerability and empowerment: Evidence from South West Nigeria. Partnership Econ. Pol. (2016)

Islam, K.J.: Does microcredit reduce household vulnerability to poverty? Empirical evidence from Bangladesh. J. Econ. Dev. Stud. 2(2), 311–326 (2014)

Islam, D., Sayeed, J., Hossain, N.: On determinants of poverty and inequality in Bangladesh. J. Poverty 21(4), 352–371 (2016)

Jain, M.K., Muñoz, T.B.:. Do rural microcredit borrowers fare better in reducing poverty than urban borrowers? Oikocredit, Berkenweg 7, 3818 (2017)

Khan, N.A.: The impact of micro finance on the household income and consumption level in Danyore, Gilgit-Baltistan Pakistan. Int. J. Acad. Res. Econ. Manage. Sci. 3(1)

Khanam, D., Mohiuddin, M., Hoque, A., Weber, O.: Financing micro-entrepreneurs for poverty alleviation: a performance analysis of microfinance services offered by BRAC, ASA, and Proshika from Bangladesh. J. Global Entrepreneurship Res. 8, 27 (2018)

Marshall, A.: Principles of Economic, 9th edn. The Macmillan Press Ltd, London (1984)

Mustapa, W.N.W., Al Mamun, A., Ibrahim, M.D.: Evaluating the effectiveness of development initiatives on enterprise income, growth and assets in Peninsular Malaysia. Econ. Sociol. 12(1), 39–60 (2019)

Mustapa, W.N.W., Al Mamun, A., Ibrahim, M.D.: Economic Impact of Development Initiatives on Low-Income Households in Kelantan. Social sciences, Malaysia (2018)

Mustapa, W.N., Al Mamun, A., Anuar, N.I., Naeem, H.: Microcredit and microenterprises performance in Malaysia. Int. J. Appl. Behav. Econ. 8(2), 1–13 (2019)

Nader, Y.F.: Microcredit and the socio-economic wellbeing of women and their families in Cairo. J. Socio-Econ. 3(7), 644–656 (2008)

Zainol, N.R., Al Mamun, A., Ahmad, G.B., Simpong, D.B.: Human capital and entrepreneurial ompetencies towards performance of informal microenterprises in Kelantan Malaysia. Econ. Sociol. 11(4), 31 (2018)

Olateju, A.O.: An assessment of the impact of Microfinance Programme on Socioeconomic Well-being and business growth of micro entrepreneurs in Nigeria: a case study of Cowries Microfinance Bank. Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Universiti Sains Malaysia (2016)

Omorodion, F.I.: Rural women’s experiences of micro-credit schemes in Nigeria case study of ESAN women. J. Asian African Stud. 42(6), 479–494 (2007)

Peprah, J.A.: Access to micro-credit well-being among women entrepreneurs in the Mfantsiman Municipality of Ghana. Int. J. Fin. Bank. Stud. 1(1), 1–14 (2012)

Ryan, W.: Blaming the Victim. Vintage, New York (1976)

Rokhim, R., Adam, G., Sikatan, S., Lubis, A., Setyawan, M.I.: Does microcredit improve wellbeing? Evidence from Indonesia. Humanomics 32(3), 1–27 (2016)

Rooyen, C.V.: The impact of microfinance in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review of the evidence. World Dev. 40(11), 2249–2262 (2012)

Samer, S., Majid, I., Rizal, S., Muhamad, M., Halim, S., Rashid, N.: The impact of microfinance on poverty reduction: empirical evidence from Malaysian Perspective. Procedia – Soc. Behav. Sci. 195, 721–728 (2015)

Siwar, C., Ahmed, F., Bashawir, A., Mia, M.S.: Urbanization and urban poverty in Malaysia: consequences and vulnerability. J. Appl. Sci. 16(4), 154–160 (2016)

Tammili, F.N., Mohamed, Z., Terano, R.: Effectiveness of the microcredit program in enhancing micro-enterprise entrepreneurs’ income in Selangor. Asian Soc. Sci. 14(1) (2018)

Terano, R., Zainalabidin, M., Hakimi, J.H.: Effectiveness of microcredit program and determinants of income among small business entrepreneurs in Malaysia. J. Global Entrepreneurship Res. 5(22), 1–14 (2015)

Ulimwengu, J., Funes, J., Headey, D., You, L.: Paving the Way for Development? The Impact of Transport Infrastructure on Agricultural Production and Poverty Reduction in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Discussion Paper 00944, International Food Policy Research Institute (2008)

Waheed, S.: Does rural micro credit improve well-being of borrowers in the Punjab (Pakistan)? Pakistan Econ. Soc. Rev. 47(1), 31–34 (2009)

Wood, G.: Staying secure, staying poor: the ‘Faustian bargain. World Dev. 31, 455–471 (2003)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Zainol, N.R., Aidara, S., Yang, M., Al Mamun, A., Mohd, F. (2021). Microcredit and Economic Wellbeing: A Study Among the Urban and Rural Members of Amanah Ikhtiar Malaysia (AIM). In: Alareeni, B., Hamdan, A., Elgedawy, I. (eds) The Importance of New Technologies and Entrepreneurship in Business Development: In The Context of Economic Diversity in Developing Countries. ICBT 2020. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 194. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69221-6_81

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69221-6_81

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-69220-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-69221-6

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)