Abstract

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between perceived HRM practices and faculty members’ turnover intention. Drawing on the social exchange theory, we hypothesised that perceived HRM negatively relates to turnover intention and that perceived job opportunities has a moderating effect on this relationship. The data was collected from 170 Pakistani full-time faculty members that were conveniently available. The hypotheses were tested using partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). The results provided support for the negative relationship between perceived HRM practices and turnover intentions. The findings also revealed that job opportunity moderated the negative relationship between HRM practices and turnover intentions. The cross-sectional nature of the study and the use of a single source for data collection limit the generalizability of the study. This study helps HR professionals in designing strategies that not only reduce faculty turnover but also provide competitive advantages to the organization over its competitors in terms of attracting and retaining employees. The study is the first of its kind that examined the moderating effect of job opportunities on HRM practices-turnover intention relationship. Besides, this is the only study on HRM practices, job opportunities and turnover intention from the perspective of faculty members working in higher education and Pakistan.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Perceived human resource management (HRM) practices

- Turnover intention

- Social exchange theory

- Job opportunities

- Intention to leave

1 Introduction

Over the last few decades, the issue of faculty members turnover intention is receiving the attention of researchers and practitioners. This issue is critically important because, on the one hand, faculty members are the source of organisations’ competitive advantages, productivity (Aboramadan et al. 2020; Webber 2018), and quality education (Ashraf 2019). While, on the other hand, their turnover results in loss of organisations’ productivity, work disruption (Gibbs 2018), employees’ demoralisation (Asrar-ul-Haq et al. 2019), and flight of intellectual capital. Besides, the high turnover rate of the faculty members not only diminishes the motivation and morale of the current faculty members, but it also affects students learning and research activities (Asrar-ul-Haq et al. 2019). Hence, higher education institutions (HEIs) spend a vast amount of money to attract, select, train, and retain faculty members. A recent study shows that 52% of the faculty members had considered leaving their current job (Kim and Rehg 2018). Thus, a better understanding of why faculty members leave their current jobs and move to other organisations should allow organisations to improve their retention efforts and reduce their academic members’ turnover.

Several studies have attempted to address this issue of faculty retention by exploring the impact various factors such as bullying at the workplace (Ahmad et al. 2017; Meriläinen, et al. 2019), job security, professional maturity, salary (Caraquil et al. 2016), work-life balance, faculty morale (Johnsrud and Rosser 2002), organisation politics (Asrar-ul-Haq et al. 2019), job opportunities (Daly and Dee 2006), job-hopping and organisation commitment (Smart 1990) on faculty members turnover intention. In addition, other studies have examined the influence of human resource management (HRM) practices on faculty members’ organisation commitment and engagement (Aboramadan et al. 2020). However, the potential effects of faculty members’ perception of HRM practices on their turnover intention have received little attention in the academic literature.

Only few researchers such as Kakar et al. (2019) have made attempts to study the effects of perceived HRM practices on faculty turnover intention. Despite offering useful insights, a major limitation of this study was ignoring the moderating role of job opportunities in the relationship between HRM practices and turnover intention. Hence, this research paper aims to examine the influence of perceived HRM practices on faculty members turnover intention, and what role do job opportunities play in determining HRM practices-turnover intention relationships?. In doing so, this study makes contributions to the literature in the following ways. First, it examines the effects of perceived HRM practices on faculty turnover intention. Second, this is among the first studies that examine the moderating role of job opportunities in the relationship between HRM practices and turnover intention, especially in the context of HEIs in Pakistan.

2 Literature Review

2.1 Perceived Human Resource Management Practices

Various conceptualisations and definitions of HRM practices exist in the literature. For instance, Schuler and Jackson (1987) define HRM practices as a system that attract, select, train, motivate and retain employees, whereas Delery and Doty (1996) view it as a set of integrated policies and practices designed and implemented to achieve organisational goals. According to another conceptualisation, HRM practices is a collective name of an organisation’s activities concerned with recruitment, selection, training, performance appraisal, compensation, development and management of its employees (Huselid 1995; Wall and Wood 2005). Likewise, Appelbaum et al. (2000) viewed HRM practices as a set of practices designed by the organisation to enhance individual abilities, motivation, and provide opportunities in order to achieve organisational effectiveness. Boxall and Purcell (2011) have conceptualised HRM practices into three different groups: the intended, actual, and perceived HRM practices. The intended HRM practices are designed by top management and can be found in the HR manual (Boxall and Purcell 2011). The intended HRM practices are concerned with employees’ ability, motivation, and opportunity to participate (Boxall and Purcell 2011). The actual HRM practices are those practices which are actually applied by the line manager or supervisor and may differ from intended HRM practices (Boxall and Purcell 2011; Nishii and Wright 2008). Perceived HRM practices refer to employees’ subjective evaluations, interpretation, and the actual experience of intended HRM practices (Boxall and Purcell 2011; Nishii and Wright 2008). Bowen and Ostroff (2004) suggested that perceived HRM practices differ from an organisation intended and actual HRM practices, as employees perceive the same set of HRM practices differently.

Collectively, HRM practices aim to achieve desired work outcomes such as, building long term relationships with employees, enhancing employees skills and knowledge (Appelbaum et al. 2000; Jiang et al. 2012), strengthening employees organisation commitment, engagement (Aboramadan et al. 2020), and reducing their burnout and turnover (Huselid 1995). However, research shows that it is not HRM practices intended by the organisation that is important in HRM practices and work outcomes relationships, but rather how employees perceive those practices (Bowen and Ostroff 2004; Farndale and Sanders 2017; Nishii and Wright 2008). Besides, scholars suggest that when the objective of the research is to investigate individual outcomes (e.g., turnover intention), then understanding HRM practices from employees’ perspectives are effective and desirable techniques (Jiang et al. 2017). Hence, this study focuses on perceived HRM practices and how it relates to faculty members turnover intention.

2.2 Turnover Intention

Turnover intention is defined as the probability of leaving the job in the near future (Sousa-Poza and Henneberger 2004). Mashile et al. 2019, Wells et al. (2016) conceptualised turnover intention as a cognitive or thinking process in which employees plan or desire to quit the job. According to Sager et al. (1998), turnover intention reflects individuals’ mental decisions intervening between attitudes toward a job and the decision of whether or not to quit the job. Earlier theories and empirical research suggest that turnover intention is the last stage of withdrawal cognition (Ajzen 1991; Steers and Mowday 1981; Mobley 1977), and has been viewed as an immediate predictor of actual leaving behaviour (Allen et al. 2010; Rubenstein et al. 2018). Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) in attitude theory of reasoned action stated that “the best single predictor of an individual’s behaviour will be a measure of his intention to perform that behaviour” (p. 369). Hence, in line with this stream of research, the focus of this study is on turnover intention rather than actual leaving behaviour.

2.3 Job Opportunity

Job opportunity is defined as the availability of job alternatives outside the organisation (Hofaidhllaoui and Chhinzer 2014). It reflects an employee’s belief that a prospective and lucrative job exists outside the organisation. According to Weng and McElroy (2012), job opportunities serve as a psychological force that motivates turnover intentions. For example, Rathi and Lee (2015) stated that when employees believe that alternative job opportunities are available outside the organisation, then their thinking of leaving the job will be high. In contrast, when job opportunities are rare, their thought of leaving the job will be low. This view is consistent with March and Simon (1958) arguments that “under nearly all conditions the most accurate single predictor of labour turnover is the state of the economy when jobs are plentiful, voluntary movement is high; when jobs are scarce, voluntary turnover is small” (p. 100).

Moreover, job opportunities act as a ‘jarring’ event that initiates a psychological process where employees seek to adjust his/her level of fit with the environment (Lee et al. 1999). If employees perceive that alternative job opportunities match their values and goal, they are more likely to quit the current job or vice versa (Wheeler et al. 2005). Weiler (1985) noted that 21% of faculty member attributed attractive employment opportunities outside the organisation for their switchover. Prior researchers have also found evidence about the positive association between job opportunities and intention to quit (Hofaidhllaoui and Chhinzer 2014; Treuren 2013) and negative relationship between job opportunities and intention to stay (Ababneh 2016). Similiarly, Daly and Dee (2006) found a negative relationship between job opportunities and academic intention to leave the job.

Although job opportunities continue to receive ample attention in organisational research (e.g., Weiler 1985; Wheeler et al. 2005; Daly and Dee 2006), yet, to date, the moderating impact of job opportunities on HRM practices and turnover intention is under-studied. Therefore, we conducted this study to understand the influence of job opportunities on HRM-turnover intention relationship. To achieve this goal, the authors present the formulation of hypotheses, results, and discussions in the following sections.

2.4 HRM Practices, Turnover Intention, and Job Opportunity

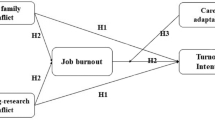

Since this study explores the relationship between perceived HRM practices and faculty members’ turnover intention, considering the moderating role of job opportunities, therefore, it is essential to theories the relationship between these constructs (Fig. 1). Though researchers have confirmed that perceived HRM practices and turnover intention are negatively related (Lam et al. 2009; Alfes et al. 2012), yet, the moderating role of job opportunities on this relationship is unexplored.

Alfes et al. (2012), in a study on a sample of UK based organisation, found that employees perception of HRM practices (i.e., training and development, selection, career management, promotion opportunity, and appraisal system) was negatively related to their intention to leave the job. In a similar vein, Lam et al. (2009) found that Sino-Japanese joint venture employees’ perception of training and compensation was negatively related to their desire to quit the job. Although these studies document the negative relationship between HRM practices and turnover intention, none of the studies was conducted in academic work settings. This is a critical oversight as research shows that work setting has a significant influence on employees’ perception of HRM practices (Farndale and Sanders 2017; Nishii and Wright 2008). In this study, we expect that faculty members’ perception of HRM practices (i.e., recruitment and selection, training and development, job security, performance appraisal, compensation, and career management) is negatively related to their intention to leave the job.

To explain this relationship, we refer to Blau’s (1964) social exchange theory. This theory posits that employment relationships (i.e., the relationship between employee and employer) depend upon social exchanges. Social exchanges are voluntary actions, “which may be initiated by organisation’s treatment of its employees, with the expectation that such a treatment will eventually be reciprocated” (Gould-Williams and Davies 2005, p. 3). On the other hand, an organisation’s treatment of its employees (e.g., the provisions of HRM practices by the organisation) is seen by the employees as an investment in them. When employees perceive their organisation to be investing in them by providing HRM practices (Kuvaas 2008; Alfes et al. 2012), they are more likely to reciprocae a wide range of positive work outcomes. For instance, employees’ positive perception of HRM practices increases organisation commitment (Kooij and Boon 2018), organisation citizenship behavior (Lam et al. 2009), and employees’ well-being (Alfes et al. 2012). On the other hand, a negative perception of HRM practices instigates burnout, emotional exhaustion (Kilroy et al. 2016), and turnover intention (Kuvaas 2008; Lam et al. 2009; Alfes et al. 2012). Hence, keeping in view these findings, it is plausible to propose that:

H1: Faculty members’ positive perception of HRM practices are negatively related to their intention to leave the job.

As mentioned above, turnover intention reflects individuals’ mental decisions intervening between attitudes toward a job and the decision of whether or not to quit the job (Sager et al. 1998); and this decision may change depending upon several factors including the perception of HRM practices and external job opportunities. Previous research has shown that employees’ perception of HRM practices is negatively related to intention to leave the job (Lam et al. 2009; Alfes et al. 2012). The present study assumes that this relationship is moderated by employees’ perception of job opportunities. For instance, in case of a negative perception of HRM practices, a faculty member who has limited job opportunities is more likely to stay with the organisation than a faculty member who has numerous alternative job opportunities. Research also demonstrates that faculty members are more likely to quit the job when they perceive the existence of job opportunities outside the organisation (Daly and Dee 2006; Rathi and Lee 2015).

Although research on the moderating influence of job opportunities on HRM practices and turnover relationship is scarce, other studies have found that job opportunity is a significant moderator of the relationship between turnover intention and its antecedents. For example, Hofaidhllaoui and Chhinzer (2014) found that job opportunities moderated the negative relationship between turnover intention and job satisfaction. Similarly, Swider et al. (2011) and Gardner et al. (2015) in their studies report the significant moderating role of job opportunities between turnover intention, self-esteem, and job search, respectively. These scholars suggest that employees with positive perceptions of the availability of job opportunities tend to have a higher intention to leave the job than those with a low perception of job opportunities. Based on this premise, we predict that job opportunities may also moderate the relationship between HRM practices and turnover intention. This idea is based on the observation that when job opportunities are high, faculty members are more likely to quit the job as they have more alternative employment opportunities. On the other hand, when job opportunities are rare, faculty members’ tendency toward leaving the job will be low because they have fewer employment opportunities in the labor market. Hence, we predict that the availability of job alternatives will moderate the influence of HRM practices on faculty members’ intention to quit.

H2: The relationship between employees’ perceptions of HRM practices and turnover intention is moderated by employees’ perceptions of job opportunities..

3 Methodology

3.1 Sampling and Design

Since the purpose of this study was to ascertain the implications of HRM practices in higher education institutions, therefore, the target population of this study were full-time faculty members of public sector colleges in Baluchistan, Pakistan. Research has also shown that faculty members turnover is a significant area of concern (Jin et al. 2018; King et al. 2018), and their perception of HRM practices is relatively poor (Naeem et al. 2019).

For this study, the minimum sample size was calculated using G*power analysis. With an estimated effect size of 0.15, α error = 0.05, and 1 – β = .95, the G*power analysis resulted in a minimum sample size of 74. However, a total of 280 questionnaires were self-administered among conveniently available faculty members. Out of 280 questionnaires, 177 were returned (61% response rate). From 177 surveys, 7 cases were deleted based on suspicious responses (e.g., straight-lining) and missing values. Hence, the final data for analysis was 170 cases.

The demographic details of the participants are shown in Table 1. The statistics in Table 1 reveals that the majority of the participants were male, i.e., 71.8%, and only 28.2% were female. Further, the sample consisted of lecturers (68.2%), assistant professors (28.8%), associate professors (2.4%), and professors (0.6%). The age of the participants ranged between 25 and 65 years.

3.2 Instruments

Five-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree = 1” to “Strongly Agree = 5” were used to measure the instruments. For the measurement of HRM practices, eight items were adapted from Alfes et al. (2012). The sample item for HRM practices includes, “I receive the training I need to do my job”. The job opportunity was measured with four items adopted from Daly and Dee (2006), and the sample item is, “There are plenty of good jobs that I could have”. The turnover intention was measured with five items adopted from Cennamo and Gardner (2008), O’Reilly et al. (1991), and the sample item is, “As soon as I can find a better job, I will leave the current job”.

3.3 Results and Analysis

Mean, Standard Deviation, and Correlations

The mean, standard deviation, and zero-order correlations among variables (Table 2) revealed that HRM practices have significant and negative, and job opportunities have significant and positive associations with turnover intention.

3.4 Analysis Method

The present study employed partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) to test the hypothesised relationship between constructs. PLS-SEM was used because it does not make distributional assumptions and maximise the explained variance of the dependent latent construct. The assessment of the model was carried out in two steps. In the first steps, the measurement model was assessed for reliability and validity. The second step involved the assessment of the structural model for path coefficients and moderation analysis. SmartPLS 3.2.8 was used for data analysis (Ringle et al. 2015).

3.5 Measurement Model Evaluation

The evaluation of the measurement model includes constructs and items reliability and validity. The reliability of items was assessed via factor loadings (Table 3). All items factor loading were well above the threshold of 0.60 (Byrne 2016). The reliability of the scales was assessed via Cronbach Alpha (CA) and Composite Reliability (CR; Table 3). All scales of CA and CR were well above the threshold of 0.70 (Hair et al. 2011). The scales were also subject to convergent and discriminate validity. The average variance extracted (AVE) satisfies the requirements for convergent validity of 0.5 for all constructs (Table 3). Furthermore, the results of the Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion (Table 4) revealed that the correlation of constructs with other constructs of the model was less than the square root of AVE of all constructs, thus affirming that discriminate validity was not an issue in the model. Likewise, Henseler et al. (2014) proposed heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) values were well below the threshold of 0.90 (Table 4), thus affirming that all constructs are distinct from each other.

3.6 Structural Model

The structural model refers to the relationships between the latent constructs of the study. The assessment of the structural model was done by estimating the model’s predictive capabilities (R2) (Chin and Dibbern 2010), Cohen’s (1988) effect size (f2), and path coefficients (β).

R2 reflects the amount of variance in the endogenous (dependent) construct accounted for by all exogenous constructs of the model. In this study, the model explained 31.50% (R2 = 0.315) variance in the dependent variable (turnover intention), which is well above the recommended value of 0.10 (Falk and Miller 1992). We also calculated the model’s effect size (f2) using Cohen’s (1988) equation. The effect size for HRM practices was 0.05, and for the interaction term (HRM*JO) was 0.03, implying that both HRM practices and interaction terms of HRM*JO had a weak effect on intention to quit the job.

Moreover, the significance of the path coefficient (β) was estimated using bootstrapping procedures (5000 resample). The findings (Table 5) revealed that perceived HRM practices had a negative and significant impact on intention to quit the job (β = −0.186, p > 0.05), thus providing support for H1. For the assessment of the moderating role of job opportunities, Hair et al. (2017) recommended two-stage approach was used. This approach involves the multiplication of the latent score of the exogenous construct with the moderator. In this study, the indicators of both constructs were standardised before multiplication to avoid multicollinearity. In the second stage, an interaction term of HRM practices and job opportunities (HRM*JO) was created. Finally, PLS bootstrapping was run in SmartPLS 3.2.8. The findings of the moderation analysis revealed that job opportunities moderated the negative relationship between HRM practices and turnover intention (β = 0.14, p > 0.05, LLCI 0.001 – ULCI 0.238). The graphical representation of the moderation analysis (Fig. 2) also shows that faculty members with higher job opportunities were more likely to quit than those with a low level of job opportunities.

4 Discussion and Conclusions

Following social exchange theory, this study examined the relationship between perceived HRM practices, job opportunities, and turnover intention. Specifically, this study investigated whether job opportunities moderate the negative influence of HRM practices on faculty members’ turnover intention. The findings revealed that HRM practices had a negative impact on faculty members’ turnover intention. This finding implies that faculty members’ positive perception of HRM practices will engender a sense of feeling among them that they are treated well by the organisation. This feeling of being good treatment on the part of the organisation is then reciprocated with lower turnover intention. The finding of this study is aligned with the proposition of Blau’s (1964) SET that individual reciprocates fair and supportive treatment from their organisations with positive work outcomes such as lowering the intention to quit. Furthermore, this result is also consistent with other studies such as Lam et al. (2009) and Alfes et al. (2012) that have found similar results, albeit in non-academic work settings.

The findings also revealed that job opportunities moderated the effect of HRM practices on turnover intention. In other words, faculty members who believed that job opportunities exist in the market were more likely to quit the job than those who had low belief in the existence of job opportunities. This finding is parallel to the conclusions of Rubenstein et al. (2018) that job opportunity is a significant moderator of turnover intention and their antecedents. Besides, the moderating role of job opportunities between HRM practices and turnover intention also substantiates and provides empirical support to the HRM contingency approach. This approach suggests that the performance of HRM practices is subject to contextual and environmental factors (e.g., job opportunities; Banks and Kepes, 2015). In addition, the finding of this study concurs Gardner et al. (2015), Hofaidhllaoui and Chhinzer (2014), Nelissen et al. (2017) conclusions that job opportunities are the significant moderators of turnover intention and their respective antecedents (e.g., self-esteem, development activities, and job satisfaction).

4.1 Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study provides several theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, this research extends the body of knowledge regarding the HRM contingency approach by examining the effectiveness of HRM practices on faculty members’ intention to quit in the context of Pakistan. Previous studies in this research area were mainly conducted in Western countries (Alfes et al. 2012; Kooij and Boon 2018), which can not be generalised to the Asain context. The present study takes one step further by examining job opportunity as a moderator between HRM practices and turnover intention, which, to the best of authors’ knowledge, has rarely been empirically investigated. The study revealed that HRM practices are less effective when job opportunities are in abundance in the market; thus, HR professionals need not only focus on HRM practices but also keep an eye on the existing labor market conditions.

Practically, this study helps HR professionals in reducing faculty turnover in numerous ways. For instance, this study found that faculty perception of HRM is important in their decision to quit or not quit the job. Therefore, mere provisions of HRM practices set by the top management may not be practical; instead, management needs to ask faculty members of what sorts of HRM practices they need and prefer. For example, some faculty members may prefer ability-enhancing practices (e.g., training and development), while others may prefer compensation-related practices. In this case, adopting HRM practices that are preferred by the majority of the faculty members would be an appropriate strategy. Besides, adopting HRM practices in line with external job markets would better able HR professionals to reduce turnover intention. For example, providing competitive pay, benefits, and growth and development opportunities (internal job opportunities) will enhance management efforts in reducing faculty turnover intention.

4.2 Limitations and Directions for Future

Despite theoretical and practical implications, this study has certain limitations. First, cross-sectional nature and small sample size limit the generalisability of the findings. Second, the results of the study are subject to common method bias because the data were collected at a particular point in time and from a single source. Moreover, this study only investigated the moderating impact of job opportunities. Future researchers may examine whether or not other organisational and environmental factors such as perceived employability, job offer, organisational culture, national norms, and values would moderate HRM practices-turnover intention.

References

Ababneh, K.I.: Effects of met expectations, trust, job satisfaction, and commitment on faculty turnover intentions in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 31, 1–32 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1255904

Aboramadan, M., Albashiti, B., Alharazin, H., Dahleez, K.A.: Human resources management practices and organisational commitment in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 34, 154–174 (2020)

Ahmad, S., Kalim, R., Kaleem, A.: Academics’ perceptions of bullying at work: Insights from Pakistan. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 31(2), 204–220 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-10-2015-0141

Ajzen, I.: The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50, 179–211 (1991). https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Alfes, K., Shantz, A., Truss, C.: The link between perceived HRM practices, performance and well-being: the moderating effect of trust in the employer. Hum. Res. Manag. J. 22(4), 409–427 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12005

Allen, D.G., Bryant, P.C., Vardaman, J.M.: Retaining talent: replacing misconceptions with evidence-based strategies. Acad. Manag. Pers. 24(2), 48–64 (2010). https://doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2010.51827775

Appelbaum, E., Bailey, T., Berg, P.B., Kalleberg, A.L., Bailey, T.A.: Manufacturing Advantage: Why High-Performance Work Systems Pay Off. Cornell University Press, Ithaca (2000)

Ashraf, M.A.: Influences of working condition and faculty retention on quality education in private universities in Bangladesh: an analysis using SEM. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 33(1), 149–165 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-03-2018-0121

Asrar-ul-Haq, M., et al.: Impact of organisational politics on employee work outcomes in higher education institutions of Pakistan: Moderating role of social capital. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 8(2), 185–200 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-07-2018-0086

Banks, G.C., Kepes, S.: The influence of internal HRM activity fit on the dynamics within the “black box.” Hum. Res. Manag. Rev, 25(4), 352–367 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.02.002

Blau, P.M.: Exchange and power in social life. John Wiley & Sons, New York (1964). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203792643

Bowen, D.E., Ostroff, C.: Understanding HRM-firm performance linkages: the role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Acad. Manag. Rev. (2004). https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2004.12736076

Boxall, P., Purcell, J.: Strategy and human resource management. Macmillan International Higher Education (2011)

Byrne, B.M.: Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming. Routledge, Abingdon (2016)

Caraquil, J.A., Yepes, P.I.G., Sy, F.A.R., Daguplo, M.S.: Simulation modeling of intention to leave among faculty in higher education institutions. J. Educ. Hum. Res. Dev. 37(37), 26–37 (2016)

Cennamo, L., Gardner, D.: Generational differences in work values, outcomes and person-organisation values fit. J. Manag. Psychol. 23(8), 891–906 (2008)

Chin, W.W., Dibbern, J.: Handbook of Partial Least Squares. How to Write Up and Report PLS Analyses. Springer, New York (2010)

Cohen, J.: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Erlbaum, Hillsdale (1988)

Daly, C.J., Dee, J.R.: Greener pastures: faculty turnover intent in urban public universities. J. High. Educ. 77(5), 776–803 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2006.11778944

Delery, J.E., Doty, D.H.: Modes of theorising in strategic human resource management: tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Acad. Manag. J. 39(4), 802–835 (1996)

Falk, R.F., Miller, N.B.: A Primer for Soft Modeling. University of Akron Press, Akron (1992)

Farndale, E., Sanders, K.: Conceptualising HRM system strength through a cross-cultural lens. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 28(1), 132–148 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1239124

Fishbein, M., Ajzen, I.: Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research (1975)

Fornell, C., Larcker, D.F.: Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18(1), 39 (1981). https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Gardner, D.G., Huang, G., Niu, X., Pierce, J.L., Lee, C.: Organisation-based self-esteem, psychological contract fulfillment, and perceived employment opportunities: a test of self-regulatory theory. Hum. Res. Manag. 54(6), 933–953 (2015)

Gibbs, T.: Making sure crime does not pay: recent efforts to tackle corruption in Dubai: the 2016 creation of the Dubai economic security centre. J. Money Laund. Control 21(4), 555–566 (2018)

Gould-Williams, J., Davies, F.: Using social exchange theory to predict the effects of HRM practice on employee outcomes. Public Manag. Rev. 7(1), 1–24 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1080/1471903042000339392

Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M.: PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19(2), 139–152 (2011). https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M.: A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2017)

Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M.: A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43(1), 115–135 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hofaidhllaoui, M., Chhinzer, N.: The relationship between satisfaction and turnover intentions for knowledge workers. EMJ – Eng. Manag. J. 26(2), 3–9 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1080/10429247.2014.11432006

Huselid, M.A.: The impact of human resource management practices on turnover , productivity, and corporate financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 38(3), 635–872 (1995)

Jiang, K., Hu, J.I.A., Liu, S.: Understanding employees’ perceptions of human resource practices: effects of demographic dissimilarity to managers and coworkers. Hum. Res. Manag. 56(1), 69–91 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1002/HRM.21771

Jiang, K., Lepak, D., Hu, J., Baer, J.: How does human resource management influence organizational outcomes? a meta-analytic investigation of mediating mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 55(6), 1264–1294 (2012). https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0088

Jin, M.H., McDonald, B., Park, J.: Person-organization fit and turnover intention: exploring the mediating role of employee followership and job satisfaction through conservation of resources theory. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 38(2), 167–192 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X16658334

Johnsrud, L.K., Rosser, V.J.: Faculty members’ morale and their intention to leave: a multilevel explanation. J. Higher Educ. 73(4), 518–542 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2002.0039

Kakar, A.S., Saufi, R.A., Mansor, N.N.A.: Person-organisation fit and job opportunities matter in HRM practices-turnover intention relationship: A moderated mediation model. Amazonia Investiga 8(20), 155–165 (2019)

Kilroy, S., Flood, P.C., Bosak, J., Chênevert, D.: Perceptions of high involvement work practices, person-organization fit, and burnout: a time-lagged study of health care employees. Hum. Res. Manag. 44(5), 1–5 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm

Kim, H., Rehg, M.: Faculty performance and morale in higher education: a systems approach. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 35(3), 308–323 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2495

King, V., Roed, J., Wilson, L.: It’s very different here: practice-based academic staff induction and retention. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 40(5), 470–484 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1496516

Kooij, D.T.A.M., Boon, C.: Perceptions of HR practices, person–organisation fit, and affective commitment: the moderating role of career stage. Hum. Res. Manag. J. 28(1), 61–75 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12164

Kuvaas, B.: An exploration of how the employee-organisation relationship affects the linkage between perception of developmental human resource practices and employee outcomes. J. Manag. Stud. 45(1), 1–25 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00710.x

Lam, W., Chen, Z., Takeuchi, N.: Perceived human resource management practices and intention to leave of employees: the mediating role of organisational citizenship behaviour in a Sino-Japanese joint venture. Int. J. Hum. Res. Manag. 20(11), 2250–2270 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190903239641

Lee, T.W., Mitchell, T.R., Holtom, B.C., Mcdaniel, L.S., Hill, J.W., Mitchell, T.R., Hill, J.W.: the unfolding model of voluntary turnover : a replication and extension. Acad. Manag. J. 42(4), 450–462 (1999)

March, J.G., Simon, H.A.: Organizations. John Wiley & Sons, New York (1958)

Mashile, D.A., Munyeka, W., Ndlovu, W.: Organisational culture and turnover intentions among academics: a case of a rural-based university. Stud. Higher Educ. 46, 1–9 (2019)

Meriläinen, M., Nissinen, P., Kõiv, K.: Intention to leave among bullied university personnel. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 33, 1686–1704 (2019)

Naeem, A., Mirza, N.H., Ayyub, R.M., Lodhi, R.N.: HRM practices and faculty’s knowledge sharing behavior: mediation of affective commitment and affect-based trust. Stud. Higher Educ. 44(3), 499–512 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1378635

Nelissen, J., Forrier, A., Verbruggen, M.: Employee development and voluntary turnover: testing the employability paradox. Hum. Res. Manag. J. 27(1), 152–168 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12136

Nishii, L.H., Wright, P.M.: Variability within organisations : implications for strategic human resource management. In: The people make the place: Dynamic linkages between individuals and organisations (D. B. S, pp. 225–248). Routledge (2008)

O’Reilly, C.A., Chatman, J., Caldwell, D.F.: People and organisational culture: a profile comparison approach to assessing person-fit. Acad. Manag. J. 34(4), 487–516 (1991)

Rathi, N., Lee, K.: Retaining talent by enhancing organisational prestige: an HRM strategy for employees working in the retail sector. Pers. Rev. 44(4), 454–469 (2015)

Ringle, C.M., Wende, S., Becker, J.-M.:SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH (2015). https://www.smartpls.com

Rubenstein, A.L., Eberly, M.B., Lee, T.W., Mitchell, T.R.: Surveying the forest: a meta-analysis, moderator investigation, and future-oriented discussion of the antecedents of voluntary employee turnover. Pers. Psychol. 71(1), 23–65 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12226

Sager, J.K., Griffeth, R.W., Hom, P.W.: A comparison of structural models representing turnover cognitions. J. Vocat. Behav. 53(2), 254–273 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1997.1617

Schuler, R.S., Jackson, S.E.: Linking competitive strategies with human resource management practices. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1(3), 207–219 (1987). https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.1987.4275740

Smart, J.C.: A causal model of faculty turnover intentions. Res. High. Educ. 31(5), 405–424 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992710

Sousa-Poza, A., Henneberger, F.: Analysing job mobility with job turnover intentions: an international comparative study. J. Econ. Issues 38(1), 113–137 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2004.11506667

Steers, R.M., Mowday, R.T.: A model of voluntary employee turnover. Res. Organ. Behav., 233–281 (1981)

Swider, B.W., Boswell, W.R., Zimmerman, R.D.: Examining the job search-turnover relationship: the role of embeddedness, job satisfaction, and available alternatives. J. Appl. Psychol. 96(2), 432–441 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021676

Treuren, G.: The relationship between perceived job alternatives , employee attitudes and leaving intention. The relationship between perceived job alternatives, employee attitudes and leaving intention, pp. 1–18 (2013)

Wall, T.D., Wood, S.J.: The romance of human resource management and business performance, and the case for big science. Hum. Relat. 58(4), 429–462 (2005)

Webber, K.L.: Does the environment matter? Faculty satisfaction at 4-year colleges and universities in the USA. High. Educ. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0345-z

Weiler, W.C.: Why do faculty members leave a university? Res. High. Educ. 23(3), 270–278 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00973790

Wells, J.B., Minor, K.I., Lambert, E.G., Tilley, J.L.: A model of turnover intent and turnover behavior among staff in juvenile corrections. Crim. Justice Behav. 43(11), 1558–1579 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854816645140

Weng, Q., McElroy, J.C.: Organisational career growth, affective occupational commitment and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 80(2), 256–265 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.014

Wheeler, A.R., Buckley, M.R., Halbesleben, J.R.B., Brouer, R.L., Ferris, G.R.: The elusive criterion of fit” revisited: toward an integrative theory of multidimensional fit. Res. Pers. Hum. Res. Manag. 24(05), 265–304 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(05)24007-0

Mobley, W.H.: Intermediate linkage in the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 62(2), 237–240 (1977)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

kakar, A.S., Saufi, R.A. (2021). Human Resource Management Practices and Turnover Intention in Higher Education: The Moderating Role of Job Opportunities. In: Alareeni, B., Hamdan, A., Elgedawy, I. (eds) The Importance of New Technologies and Entrepreneurship in Business Development: In The Context of Economic Diversity in Developing Countries. ICBT 2020. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 194. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69221-6_138

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69221-6_138

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-69220-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-69221-6

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)