Abstract

Maternal imprisonment and foster care placement represent two system-enforced forms of mother-child separation. To inform policies and practices that may prevent such separations, this study examined the timing of mother’s incarceration in relation to her children’s involvement with social services, contributory factors leading to foster care placement, and foster care discharge outcomes. North Carolina administrative records from the Department of Corrections, Vital Statistics, and the Division of Social Services were used. Participants included women who entered state prison between 2006 and 2009, who had at least one child aged 0–14 years, and who had at least one child enter foster care in the 3 years before or after prison entry (N = 893 women). Outcomes were examined annually during the 3 years prior to and following maternal prison entry and included whether or not the mother had at least one child who (a) had a child protective services assessment/investigation, (b) entered foster care, (c) had parental rights terminated, and (d) exited foster care. Rates of child welfare engagement in the years prior to maternal prison entry were high, and substance-related issues were documented in over half the sample. A quarter of women had parental rights terminated, and one in six had a child adopted. This study extends prior work on the timing of maternal prison entry and her children’s social services involvement by focusing on a state prison population and investigating the contributory factors associated with foster care placement. These findings suggest opportunities that may reduce maternal-child separation by preventing future criminal justice involvement and foster care placements.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Decisions made by actors in the criminal justice and child welfare systems, separately and combined, often result in mother-child separations (Doyle & Joseph, 2007; Gifford, Evans, Kozecke, & Sloan, 2020). Decisions regarding incarceration fall under the authority of the criminal court and corrections systems, while decisions regarding foster care placements are made by the child welfare system. Structural factors impede our understanding of how often and under what conditions such separations occur. These systems have separate funding streams, accountability reporting mechanisms, and data infrastructures. Despite both serving public interests and overlapping populations, the two systems rarely coordinate prevention efforts that could potentially reduce both costly foster care placements and maternal incarcerations (Nickel, Garland, & Kane, 2009; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2011). To inform such prevention efforts, this study sought to understand the joint entanglement of women who enter state prison with her children’s involvement in child protective services and foster care.

The Timing of Maternal Incarceration and Their Children’s Child Protective Services Involvement

Only a handful of studies from a limited number of locations (New York and Illinois) have used linked administrative records to study the timing of mother’s incarceration and her children’s foster care placement(s). Administrative records are befitting for this endeavor because they document exact start and end dates of incarceration(s) and foster care placement(s) and provide reliable information on incarceration type (e.g., jail vs. prison) and details regarding the foster care entry and exit process.

Two studies examined the temporal relationship between maternal criminal involvement and children’s placement into foster care in New York City (Ehrensaft, Khashu, Ross, & Wamsley, 2003; Ross, Khashu, & Wamsley, 2004). Ehrensaft and co-authors (2003) found that among mothers whose children were in foster care, the foster care placement occurred before rather than after the maternal arrest in 70–75% of cases. This study also found that more mothers were sentenced to an incarceration in the years following their child’s entry into foster care relative to the years before foster care entry. Ross et al. (2004) focused more narrowly on maternal incarcerations that overlapped with children’s foster care stay and found that child’s placement into foster care preceded the maternal incarceration in 90% of cases.

Similar results emerged from a series of studies based on records from Illinois (IL) and jail records from Cook County, IL, the largest jail in the United States (Dworsky, Harden, & Goerge, 2011; Holst & LaLonde, 2011; Jung, LaLonde, & Varhese, 2011). For 75% of incarcerated mothers with children in foster care, the placement of their oldest children began more than a year before their own first incarceration (Holst & LaLonde, 2011). Moreover, in many cases, children’s foster care placement began and ended before their mothers’ incarceration (Jung et al., 2011). In Illinois and Cook County, 72% of foster care placements of children with incarcerated mothers began prior—typically at least a year before—their mother’s first incarceration (Dworsky et al., 2011). Taken together, these studies highlight that prior to maternal incarceration, the social service system is often involved in these families’ lives.

Termination of Parental Rights

Termination of parental rights is a potential outcome for women who enter prison (Genty, 1995). This is particularly true in light of the 1997 Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) whereby states are required to begin the process of terminating parental rights if a child has been in foster care for 15 of the previous 22 months. Approximately 1% of US children experience termination of parental rights (Wildeman, Edwards, & Wakefield, 2019). The studies from New York and Illinois found that, respectively, 2% and 3% of the mothers who were incarcerated had parental rights terminated (Jung et al., 2011; Ross et al., 2004). Others have suggested that this outcome varies by state and may be even more common cumulatively over the life course for women who experience incarceration compared to women who never experience incarceration (Wildeman et al., 2019).

Maternal Incarceration and Children’s Exit from the Foster Care System

Little is known regarding how children with incarcerated mothers exit the foster care system , including the timing of these exits in relation to the start of the incarceration. Evidence from New York and Chicago suggest that children with incarcerated parents experience relatively high rates of adoption. For example, in a New York City sample, 57% of the children of incarcerated mothers had a permanency plan that included adoption (Ehrensaft et al., 2003; Ross et al., 2004). In New York State, mothers incarcerated for 2 or more years during their lifetime were more likely to have their children adopted (Ehrensaft et al., 2003). In Illinois, when maternal incarceration overlapped with foster care, 60% of mothers had their children adopted or placed into subsidized guardianship (Jung et al., 2011). Children in foster care whose mothers were incarcerated were less likely to be reunified relative to children whose mothers were not incarcerated (Dworsky et al., 2011), and reunification was especially unlikely if a child’s placement overlapped with maternal incarceration (Jung et al., 2011).

The Current Study

The current study focused on mothers who were jointly involved in the prison and foster care system. The main aim was to understand the timing of her children’s child welfare services involvement (i.e., assessments/investigations for possible maltreatment, foster care entries and exits) in relation to the beginning of her incarceration. To gain a rich understanding of child welfare system involvement during the 3 years preceding and following prison entry, both annual point-in-time and cumulative estimates were calculated. Extending prior work, this study also examined factors which contributed to a mother having a child placed into foster care, including child maltreatment-specific factors (e.g., abuse and neglect), social factors (incarceration, housing insecurity, parental ability to cope, parental substance use), and other factors (e.g., parental death, abandonment, relinquishment), comparing rates between mothers who were and were not incarcerated. Statewide criminal corrections, birth, and child welfare records were used.

Method

Sample

The primary analytic sample was comprised of women who (a) entered prison in North Carolina between 2006 and 2009; (b) were mothers of minor children (aged 0–14) at the time of their first prison entry between 2006 and 2009; and (c) had at least one child who entered foster care during the 3 years before and/or after prison entry (n = 893). The 3-year window was chosen to reflect a window used in other investigations of foster care placements in relation to parental incarceration (Andersen & Wildeman, 2014; Dworsky et al., 2011; Gifford et al., 2020). It also reflected a practical time period for system actors to understand and evaluate how service provision may prevent adverse outcomes. Two comparison groups were created. The first was women who entered prison during this time period and were likewise mothers of minor children at prison entry (n = 893). The first prison entry during this time period was used as the index entry. The second comparison group included women who did not enter North Carolina state prison between 2006 and 2009 and who had at least one minor child at a randomly assigned counterfactual prison entry date between 2006 and 2009 (n = 9319). The unit of analysis in all calculations is the mother.

Data for this analysis came from three North Carolina state sources: the Department of Corrections (DOC) provided information on prison entries from 2006 to 2009; the Division of Social Services (DSS) provided information on children who were investigated or assessed for suspected child maltreatment and foster care placements from 2003 to 2012; and the Division of Vital Statistics provided birth records from 1992 to 2012. Maternal corrections records were linked to child DSS records via birth records. Linkages at the individual level were based on the individual’s first name, last name, birthdate, and gender. For observations that did not merge after the most stringent criteria were used, we used birthdate and last and first name, assisted with use of Soundex. The Soundex algorithm codes words or names phonetically (Fan, 2004). This study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board, the North Carolina Department of Corrections, and the North Carolina Division of Vital Statistics.

Measures

Social services involvement : Binary variables were created to examine whether or not the mother had at least one child who (1) was assessed and/or investigated by child protective services ; (2) who entered foster care ; (3) who had parental rights terminated ; and (4) who had any child exiting foster care . For termination of parental rights, we only consider termination of maternal rights, not paternal rights. A set of non-mutually exclusive variables described reasons for at least one of a mother’s children’s entry into foster care: physical abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, parent’s or child’s drug and/or alcohol misuse, child’s behavior, caregiver coping, incarceration, inadequate housing, and other (death of parent, abandonment, relinquishment, and child’s disability). The reasons in the “other” category each constituted less than 2% of the sample. A set of non-mutually exclusive variables described whether any of the women’s children exited foster care by (a) reunification, (b) adoption, (c) guardianship with a relative, (d) custody with non-removal parent or relative, and (e) other (emancipation, custody with court-approved caretaker, runaway, death of child, transfer to another agency, interstate compact placement agreement with another state was terminated, and authority revoked for other reasons).

Maternal demographic characteristics: Information obtained from their children’s birth records includes race/ethnicity (Black, White, Hispanic, other); age at prison entry (16–19, 20–25, 26–30, 31–35, and 36 years or older); highest recorded educational attainment (any schooling after high school, high school graduate, less than high school, education missing); if ever a teen parent (aged 16–19 at any child’s birth); the number of children at prison entry; the ages in years of children at prison entry (<1, 1–3, 4–6, 7–10, 11–13, 14–17); and whether or not child was born on or within 3 years of prison entry.

Criminal justice/corrections data: Variables included length of sentence (<3 months, 3–6 months, 7–12 months, 1–2 years, more than 2 years); any jail credit and number of days of jail credit; number of prior prison entries (0, 1, 2, 3, or more); and number of prior probation sentences (0, 1, 2, 3, or more). The most common offenses leading to a prison sentence were categorized as follows: violent (e.g., murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault), child and family (e.g., child abuse, domestic violence), sexual, substance related, larceny/theft, traffic, fraud, and non-aggravated assault.

Analysis

Chi-square tests were used to test the null hypothesis of homogeneity between two groups of mothers in prison (those with no children in foster care during the study window and those with at least one child who entered foster care during the study window) on characteristics such as mother’s race/ethnicity, mother’s age at prison entry, and mother’s education (Agresti & Finlay, 2009). When the results of the chi-square analysis indicated that the null hypothesis of homogenous populations could be rejected (p < 0.05), tests of proportions were conducted to assess differences (Agresti & Finlay, 2009; StataCorp, 2019). Tests of proportions were also used to test the non-mutually exclusive set of variables (e.g., age of women’s children and offenses leading to incarceration). For women in our sample, the cumulative incidence of having experienced CPS assessment/investigation, entry into foster care, exit from foster care, and termination of parental rights was calculated annually over the 3 years prior to prison entry and the 3 years following prison entry. All analyses were conducted in Stata 15 (StataCorp, 2017).

Results

Mothers Who Were in Prison: Comparing Mothers with and Without Children in Foster Care

Descriptive Characteristics

Among mothers (of children aged 0–14 years) who entered North Carolina state prison between 2006 and 2009, 16.3% had at least one child who entered foster care within 3 years before or after their prison entry (Table 1). A higher proportion of mothers with at least one child who entered foster care, relative to the other mothers in our sample, were White (55.3% vs. 67.1%, p < 0.001) and a smaller percentage were Black (28.6% vs. 40.3%, p < 0.001). For context, the female population of North Carolina during this time period was 62% White and 24% Black; thus, Black women were overrepresented among women in prison (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, & National Center for Health Statistics, 2019). Mothers who had a child enter foster care (vs. those who had not) differed in age (χ2(4) = 40.667, p < 0.001), tending to be younger [although a slightly lower percentage of the former group were teenagers at prison entry (2.1% vs. 3.8%, p = 0.0138)]. Notably, mothers with (vs. without) children who entered foster care, had on average more children, tended to have younger children, and were more likely to give birth to a child during the 3 years following prison entry, have less than a high school education, ever given birth prior to age 20 (i.e., ever a teen parent).

Mother’s Criminal Justice System Involvement

Substance-related followed by larceny/theft were the most common offenses for both groups of mothers. Mothers who had at least one child enter foster care (vs. those who did not) were more likely to have been convicted of substance-related offenses (48.6% vs. 43.8%, Z = −2.6543 p = 0.0079), traffic offenses (19.4% vs. 15.4%, Z = −2.9692 p = 0.0030), a child and family crime (4.3% vs. 2.1%, Z = −3.8060, p < 0.001), or a sex-related offense (4.0% vs. 2.2%, Z = −3.2322 p = 0.0012) (the latter two not shown).

Length of prison sentence did not differ by whether or not a mother had a child enter foster care, and for both groups, roughly two-thirds of sentences were of 6 months or less. Before entering prison, the majority of mothers had accrued jail credit (84.0% and 82.1%, Z = −1.3868 p = 0.1655 with and without a child who entered foster care, respectively); the median length of time was approximately 1 month (not shown). Most of the women had not previously been in prison (72.8% and 70.9%, Z = −1.1453 p = 0.2521); however, nearly all (95.5%) of the women had been on probation at least once and over half had been on probation two or more times (not shown).

Factors Contributing to Child’s Foster Care Placement

For women in our sample who had at least one child enter foster care, the five leading contributory factors were neglect (86.1%), parental drug and/or alcohol abuse (54.4%), caregiver’s ability to cope (23.0%), incarceration (16.2%), and inadequate housing (13.1%) (Table 2). Three of these five factors (neglect, parental drug and/or alcohol abuse, and incarceration) were identified at a higher rate for the mothers in our study sample relative to the statewide comparison sample. Notably, parental drug and/or alcohol use and incarceration were listed as a contributory factor at 1.6 times and 3.2 times more often in the study sample than the statewide comparison sample of women. Relative to mothers in the statewide comparison sample, physical abuse, child behavior, and sexual abuse were less frequently acknowledged as contributory factors among mothers in the study sample; in contrast, higher rates of child drug or alcohol use were observed in the study sample.

Timing of Social Services Outcomes for Mothers in Prison with Children in Foster Care

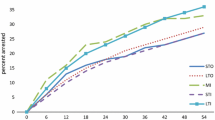

To understand mothers’ involvement with child welfare services prior to and following prison entry, we examined six 1-year cross sections and documented whether or not any of her children had experienced a specific social services event (e.g., CPS assessment/investigation, entered foster care, etc.) during that time period (Fig. 1). Importantly, in the 25–36 months (i.e., 2–3 years) before prison entry, 44.6% of mothers had at least one child with a CPS/assessment or investigation; this rate remained relatively constant in the time leading up to the incarceration and dropped following prison entry—dropping to 29.9% in the 0–1 year following prison entry. For women in the sample, 19.6% had at least one child enter foster care in the 2–3 years prior to prison entry, while this rate rose in the years leading up to prison entry—including 32.5% in the 0–12 months prior to prison entry. In the 3 years following prison entry, rates of foster care entry were lower, ranging from 13.8% to 14.8%.

Timing of social services involvement of mothers with children in foster care who enter state prison (n = 893 mothers). Note: The sample includes women with at least one child aged 0–14 years at prison entry and who had a child enter foster care within 3 years before or after the day they entered prison

Termination of parental rights , during the 25–36 and 13–24 months prior to prison entry, was uncommon. However, in the year prior to prison entry, 5.6% of women in our sample experienced termination of parental rights. Moreover, 6.7–7.2% of women in the sample had parental rights terminated in each of the 3 years following incarceration.

In each of the years prior to and following prison entry, a smaller percentage of women experienced a reunification than experienced a child exiting foster care by another means. Annually the percent of mothers in our sample who experienced reunification ranged from 2.9% to 5.7%. While the percentage of women who had at least one child who was adopted was low (<1%) in the years prior to prison entry, the rate grew in each of the years following prison entry from 4.1% to 7.4%.

Cumulative Incidence of Social Services Involvement

Beyond examining discrete time intervals, we also examined the cumulative percentage of mothers experiencing each child welfare event in the years prior to and following prison entry (Table 3). Notably, during the 3 years prior to prison entry, 81.2% of mothers had at least one child who was the subject of a CPS investigation, including 65.7% where the assessment/investigation had occurred at least a year prior to entry.

In the 3 years following prison entry, the mothers had lower cumulative rates of CPS assessments/investigations and foster care entries and higher rates of termination of parental rights and exits from foster care. A substantially higher share of women experienced termination of parental rights in the years following rather than prior to prison entry (20.0% vs. 6.0%) and the adoption of one of her children (16.2% vs. <1%).

Exit from Foster Care

To contextualize the experiences of mothers in our study sample with other mothers who have similarly aged children in foster care, rates of termination of parental rights and foster care discharge outcomes were compared (Table 4). In the ±3 years surrounding prison entry, mothers in our study sample, relative to mothers in a statewide comparison sample, experienced higher rates of termination of parental rights (25.4% vs. 14.0%, p < 0.001), lower rates of reunification (26.0% vs. 38.4%, p < 0.001), and higher rates of having a child adopted (16.8% vs. 8.1%, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Proximal to the time of prison entry, one in six mothers (of children aged 0–14 years) who entered state prison had a child who entered the foster care system. For these mothers who were jointly involved in the prison and foster care systems, a quarter had parental rights terminated, and one in six had a child adopted, rates substantially higher than other mothers with children in foster care. To inform service delivery and efforts aimed at preventing maternal incarceration and foster care entry, this study examined how and when public agencies may have been involved in these families’ lives. Prior to prison entry, nearly all of the women had been on probation. Two-thirds of the women had at least one child with an assessment or investigation by child welfare services in the 2–3 years prior to prison entry.

The rates of women who experienced termination of parental rights in this study were notably higher than in previous reports (Jung et al., 2011; Ross et al., 2004). The study from New York began with a sample of children in foster care and then examined their mother’s incarceration history (Ross et al., 2004), while the study from Illinois included mothers with short jail stays as well as prison entries (Jung et al., 2011). In contrast, this study focused on women who were in state prison and jointly had at least one child involved in the foster care system proximal to the prison entry. Thus, higher rates of termination of parental rights may highlight the vulnerability of this dually involved population.

The results of this study punctuate the need to understand how to incorporate effective strategies to provide services to families at their initial involvement with CPS. While this study could not assess substance misuse directly, the fact that nearly half of the women entered prison on a substance-related conviction and over half had a child enter foster in part due to parental substance use suggests improved efforts to substance abuse treatment may be warranted. Family drug treatment courts are one service intervention that is designed to address underlying substance misuse for families with children who are involved in the foster care system and have been demonstrated to decrease length of time children spend in foster care and increase reunification (Gifford, Eldred, Vernerey, & Sloan, 2014). However, these courts work only with caregivers who have already lost custody of a child.

In North Carolina, the civil rather than the criminal court system operates family drug treatment courts. Participation in adult drug treatment courts, which are not tailored to meet the needs of parents with children involved in CPS, did not mitigate the risk of CPS involvement (Gifford, Eldred, Sloan, & Evans, 2016). A literature review likewise found insufficient evidence to conclude that substance abuse treatment effectively prevented women who misuse substances from having their children placed into foster care (Canfield, Radcliffe, Marlow, Boreham, & Gilchrist, 2017), and others have shown that substance use treatment does not necessarily prevent recurrence of maltreatment reports (Barth, Gibbons, & Guo, 2006).

Probation is a form of court-ordered community supervision that serves as an alternative to incarceration and may include mandated services such as substance use treatment or may be limited to monitoring of behavior without services. Failing to comply with probation terms may lead to the reinstatement of one’s prison sentence. According to national estimates, among children who were assessed by child protective services and remained at home, 1 in 20 lived with a parent who was on probation at the time of the assessment; further, within 3 years, 40% of these children no longer lived with the parent who was on probation (Phillips, Leathers, & Erkanli, 2009). A recent literature review documented that women under community supervision experience considerable parenting stress and struggle with an array of issues such as a history of trauma, mental health problems, providing for their children’s basic needs, and their own health (Sissoko & Goshin, 2019). Moreover, community criminal justice programs may not be well suited to address unique needs of mothers that allow for participation such as childcare (Sissoko & Goshin, 2019).

These results suggest that prior to prison entry, multiple service entry points exist and indicate the potential for improved outcomes through cross-system collaboration. As noted in this study and others (e.g., Kennedy, Mennicke, & Allen, 2020), the needs of mothers who are incarcerated cross health and social systems as well as adult- and child-serving providers (Dallaire, Zeman, & Thrash, 2015). Fortunately, programs exist with evidence demonstrating effectiveness for preventing foster care placements and incarceration. Intensive family preservation services, when implemented with fidelity, have been documented to prevent children from entering foster care (Bezeczky et al., 2020). Moreover, correctional interventions exist to prevent recidivism among women, including substance use treatment (Gobeil, Blanchette, & Stewart, 2016).

Cautions regarding the potential pitfalls of such efforts must be considered. Coercive treatment with punitive outcomes such as loss of child custody or return to prison may not achieve the long-term desired behavioral changes of underlying issues such as substance misuse. Moreover, numerous scholars have raised concerns that cross-agency collaboration can result in extra surveillance and higher risk of child custody loss or being reported to law enforcement (e.g., Barth et al., 2006; Draine & Solomon, 2001; Drake, Jonson-Reid, & Kim, 2017). To be accessible, services must be designed around the multiple needs of women and their families and the multiple constraints (financial, time, coordinating with work schedules, and childcare availability) (Kennedy et al., 2020). Addressing such concerns as collaborative efforts are built or enhanced is critical for building trust among the women, children, and families who are served (Brayne, 2014; Fong, 2019).

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Only biological children born in North Carolina were observed, potentially excluding the social service experiences of some of the women’s children. The data lacked details on living arrangements; thus we did not know if the mother was living with the children’s father, other parental figures, or even the child. While a higher prevalence of fathers are incarcerated than mothers, children are more likely to live with their mother (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008). Thus, this study focused on maternal incarceration.

Constrained by available data (children born between 1992 and 2012), this study excluded mother’s experiences regarding her older children (aged 15–17 years) but included mother’s children who were born during our observation window. The first few years of life mark the highest risk of having a CPS investigation, experiencing confirmed maltreatment, being placed into foster care, and termination of parental rights (Kim, Wildeman, Jonson-Reid, & Drake, 2017; Wildeman et al., 2014; Wildeman et al., 2019; Wildeman & Emanuel, 2014). This analytic decision allowed comparable outcome variables to be constructed for the periods before and after prison entry.

Social service records were provided at the child level not the maternal level. While we could identify if a child had been reunified, we could not determine if the child was reunified with the mother or another caregiver. Only termination of parental rights that occurred through social services was observable—those that occurred through civil court proceedings were not assessed. Further, we could not observe cases where parental rights were restored. This study did not examine the timing of women’s prior criminal history, including arrests and convictions in relation to the incarceration and foster care placement. These points of contact could further be explored as opportunities to connect families with services. Despite these limitations, given the paucity of information on this subject, we believe that these results provide important insight on which future studies can build.

Conclusions

Mothers who jointly experience incarceration and having a child placed in foster care are at risk for permanently losing custody of their children, termination of parental rights, and adoption. Results from this study highlight that these women have high rates of engagement with child protective services prior to prison entry. A mother’s loss of child custody and her entry into prison share common underlying risk factors. Thus, policies that support investment of resources toward family preservation during these initial contacts with child protective services offer hope of preventing these adverse outcomes.

References

Agresti, A., & Finlay, B. (2009). Chapter 8. Association between categorical variables. Statistical methods for the social sciences. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Andersen, S. H., & Wildeman, C. (2014). The effect of paternal incarceration on children’s risk of foster care placement. Social Forces, 93(1), 269–298.

Barth, R. P., Gibbons, C., & Guo, S. (2006). Substance abuse treatment and the recurrence of maltreatment among caregivers with children living at home: A propensity score analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 30(2), 93–104.

Bezeczky, Z., El-Banna, A., Petrou, S., Kemp, A., Scourfield, J., Forrester, D., & Nurmatov, U. B. (2020). Intensive family preservation services to prevent out-of-home placement of children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 102, 104394.

Brayne, S. (2014). Surveillance and system avoidance: Criminal justice contact and institutional attachment. American Sociological Review, 79(3), 367–391.

Canfield, M., Radcliffe, P., Marlow, S., Boreham, M., & Gilchrist, G. (2017). Maternal substance use and child protection: A rapid evidence assessment of factors associated with loss of child care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 11–27.

Dallaire, D. H., Zeman, J. L., & Thrash, T. M. (2015). Children’s experiences of maternal incarceration-specific risks: Predictions to psychological maladaptation. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(1), 109–122.

Doyle, J., & Joseph, J. (2007). Child protection and child outcomes: Measuring the effects of foster care. The American Economic Review, 97(5), 1583–1610.

Drake, B., Jonson-Reid, M., & Kim, H. (2017). Surveillance bias in child maltreatment: A tempest in a teapot. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(9), 971.

Draine, J., & Solomon, P. (2001). Threats of incarceration in a psychiatric probation and parole service. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71(2), 262–267.

Dworsky, A., Harden, A., & Goerge, R. (2011). The relationship between maternal incarceration and foster care placement. Open Family Studies Journal, 4(Supplement 2; M5), 117–121.

Ehrensaft, M., Khashu, A., Ross, T., & Wamsley, M. (2003). Patterns of criminal conviction and incarceration among mothers of children in foster care in New York City. New York, NY: Vera Institute of Justice.

Fan, Z. (2004). Matching character variables by sound: A closer look at SOUNDEX function and sounds-like operator (=*). SAS® Users Group Institute, Paper. Retrieved March 3, 2016, from http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi29/072-29.pdf

Fong, K. (2019). Concealment and constraint: Child protective services fears and poor mothers’ institutional engagement. Social Forces, 97(4), 1785–1810.

Genty, P. (1995). Termination of parental rights among prisoners: A national perspective. In K. Gabel and D. Johnston (Eds.) Children of incarcerated parents. New York: Lexington Books, pp. 167–182.

Gifford, E. J., Eldred, L. M., Sloan, F. A., & Evans, K. E. (2016). Parental criminal justice involvement and children’s involvement with child protective services: Do adult drug treatment courts prevent child maltreatment? Substance Use & Misuse, 51(2), 179–192.

Gifford, E. J., Eldred, L. M., Vernerey, A., & Sloan, F. A. (2014). How does family drug treatment court participation affect child welfare outcomes? Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(10), 1659–1670.

Gifford, E. J., Evans, K. E., Kozecke, L. E., & Sloan, F. A. (2020). Mothers and fathers in the criminal justice system and children’s child protective services involvement. Child Abuse & Neglect, 101, 104306.

Glaze, L. E., & Maruschak, L. M. (2008). Parents in prison and their minor children. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

Gobeil, R., Blanchette, K., & Stewart, L. (2016). A meta-analytic review of correctional interventions for women offenders: Gender-neutral versus gender-informed approaches. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(3), 301–322.

Holst, R., & LaLonde, R. (2011). Does time in prison affect a mother’s chances of being reunified with her children in foster care? Evidence from Cook County, Illinois. In R. H. Susan George, H. Jung, L. L. Robert, & R. Varghese (Eds.), Incarcerated women, their children, and the Nexus with foster care. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

Jung, H., LaLonde, R., & Varhese, R. (2011). Incarcerated mothers, their children’s placements into foster care, and its consequences for reentry and labor market outcomes. In R. H. Susan George, H. Jung, L. L. Robert, & R. Varghese (Eds.), Incarcerated women, their children, and the Nexus with foster care. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

Kennedy, S. C., Mennicke, A. M., & Allen, C. (2020). ‘I took care of my kids’: Mothering while incarcerated. Health & Justice, 8(1), 1–14.

Kim, H., Wildeman, C., Jonson-Reid, M., & Drake, B. (2017). Lifetime prevalence of investigating child maltreatment among US children. American Journal of Public Health, 107, 274–280.

Nickel, J., Garland, C., & Kane, L. (2009). Children of incarcerated parents: An action plan for federal policymakers. New York: Council of State Governments Justice Center.

Phillips, S. D., Leathers, S. J., & Erkanli, A. (2009). Children of probationers in the child welfare system and their families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 18(2), 183.

Ross, T., Khashu, A., & Wamsley, M. (2004). Hard data on hard times: An empirical analysis of maternal incarceration, foster care and visitation. New York, NY: Vera Institute of Justice.

Sissoko, D. G., & Goshin, L. S. (2019). Mothering under community criminal justice supervision in the USA. In The Palgrave handbook of prison and the family (pp. 431–455). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

StataCorp. (2017). Stata statistical software: Release 15. College Station, TX: StataCorp.

StataCorp. (2019). Stata bae reference manual: Release 16. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Wildeman, C., & Emanuel, N. (2014). Cumulative risks of foster care placement by age 18 for US children, 2000–2011. PLoS One, 9, e92785.

Wildeman, C., Emanuel, N., Leventhal, J. M., Putnam-Hornstein, E., Waldfogel, J., & Lee, H. (2014). The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US Children, 2004–2011. JAMA Pediatrics, 168, 706–713.

Wildeman, C., Edwards, F. R., & Wakefield, S. (2019). The cumulative prevalence of termination of parental rights for U.S. children, 2000–2016. Child Maltreatment, 25(1), 32–42.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, & National Center for Health Statistics. (2019). Bridged-race population estimates, United States July 1st resident population by state, county, age, sex, bridged-race, and hispanic origin. Retrieved 2019, from http://wonder.cdc.gov/bridged-race-v2018.html

US Government Accountability Office. Child Welfare: More Information and Collaboration Could Promote Ties Between Foster Care Children and Their Incarcerated Parents. Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office; 2011. https://www.gao.gov/assets/590/585386.pdf.

Acknowledgements

Partial support for this work was provided by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Evidence for Action program and the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) R01DA040726. The NC Division of Social Services does not take responsibility for the scientific validity or accuracy of methodology, results, statistical analyses, or conclusions presented.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gifford, E.J., Golonka, M., Evans, K.E. (2021). Maternal Imprisonment and the Timing of Children’s Foster Care Involvement. In: Poehlmann-Tynan, J., Dallaire, D. (eds) Children with Incarcerated Mothers. SpringerBriefs in Psychology(). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67599-8_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-67599-8_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-67598-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-67599-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)