Abstract

The debate between categorical and dimensional systems has marked the history of psychiatry and psychology from its origins. The former has often been criticized as reductionist, while the latter have been considered as anti-scientific. DSM-5 retained the categorical classification of previous editions for personality disorders (PD) but integrated an alternative evaluation system with dimensional bases. This “compromise solution” between the need to preserve the clinical tradition and the imperative of overcoming important diagnostic restrictions opened the doors for a better approach. This chapter summarizes the advantages and limitations of each perspective, considering the observations that have been made to the most widespread theories of personality, as well as to evaluation instruments that derive from them. The aim is to enrich the theoretical approaches without rejecting the baggage achieved so far. We propose a moderation of the use of self-records of the patient and a deeper analysis of the experiential psychopathological history. We conclude that the dimensional alternatives do not solve all the clinical problems – cutoff point for diagnosis, overlapping of diagnostic criteria, distinction between axis I and axis II disorders, preponderance of the conscious aspects – but provide valuable resources tending to the constant refinement that is expected from any discipline.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders preserved with minimal modifications the categorical classification of previous editions for personality disorders (PD), influenced by the traditions of Schneider and Kraepelin [1]. Although some researchers predicted an imminent advance towards the installation of a dimensional system, it was imposed a period of coexistence of models suggested by others [2]. Thus, Section III of the manual presented an alternative model, conceived as a palliative for possible deficiencies derived from the use of the categorical system.

There were proposed seven general criteria to diagnose and a double assessment that includes the level of personality deterioration and the existence of pathological features [3]. That is to say that despite the fact that certain authors have noticed the poor validation and the high overlap between the diagnostic criteria of each of the disorders included in the three clusters, the definitive leap towards a dimensional-factorial system has not been made. The explicit purpose of “preserving a continuity with current clinical practice” was explicitly stated, although the inadequacy of current nosography has been empirically recognized. This chapter does not propose an exhaustive analysis of the dimensional model of the DSM-5 but a review of its potential advantages and certain limitations attributable to this type of system, considering methodological aspects involved in the generation of evidence and underlying hypotheses and problems that remain unsolved.

Critics and Limitations of the Categorial Model for PDs in the DSM-5

Explicitly, the authors of the DSM-5 postulated that their categorical perspective implies the understanding of PDs as isolated and differentiable entities [4], which contrasts with the overlapping of diagnostic criteria between different categories and the number of possible combinations that could lead to confirmation in each case. In addition, it has been pointed out that the division into three clusters (A, “eccentric”; B, “dramatic, emotional, and erratic”; and C, “anxious, fearful”) seems to be based on a simplicity criteria, despite the great amount of evidence that questions its empirical validation [1]. Even so, some of the arguments that justify their permanence cannot be dismissed either. It is due to the fact that the system expresses in a dichotomous way the decision linked to the “need or inadmissibility of administering treatment.” Moreover, it facilitates the communication and training of clinicians and aims the discussion to large pathological groups supported by a long academic tradition [2]. As a counterpart, Esbec and Echeburúa [1] have indicated that it generates a discrepancy between the patient’s symptomatology and the underlying theory, promotes inconsistencies between evaluators, and sustains superimpositions between the PDs –presumably sustained over time – and the clinical disorders traditionally ascribed to the axis I of multiaxial diagnosis.

In summary, the most relevant critics of the categorical model of the DSM seem to be based on four main axes:

-

1.

There is no empirical evidence that validates the definition of the PDs in terms of 10 dichotomous variables.

-

2.

It has not been precisely justified why a number of necessary symptoms are chosen – and not another – for a given diagnosis.

-

3.

High levels of comorbidity and overlapping between categories hinder both the clinical and the planning of investigations [4].

-

4.

The temporal endurance , the center of differentiation between PDs and clinical disorders, often is not observed in axis II diagnoses [2].

For this reason, a dimensional system would presumably help to solve certain difficulties by clarifying the diffuse limits between pathology and normality; solving the problem of comorbidity by exploring measurable traits in all people; improving the reliability of the evaluation; and helping to capture the complexity of the pathologies [1].

The Alternative Evaluation of the DSM-5

Skodol et al. [5] presented the alternative model of personality evaluation that was later reflected in the final edition of the manual. Four elements composed it:

- (a)

A scale composed of five levels of severity in personality deterioration, including an assessment of nuclear and interpersonal functioning;

- (b)

Five specific disorders, defined by pathological personality traits (Antisocial/Psychopathic, Avoidant, Borderline, Obsessive compulsive and Schizotypal).

- (c)

Six major domains of pathological features (Negative Affection, Detachment, Antagonism, Disinhibition and Psychoticism / Schizotypy), with 4 to 10 more specific facets in each;

- (d)

New General Criteria for the diagnosis of PD based on extreme or severe deficits of the nuclear capacities and functioning of the personality.

The arguments and evidence provided by the authors to support the inclusion of each element are vast. Given the objectives of this chapter, we will present them in a summary way.

Regarding the first, it has been pointed out that general severity has been identified as the most important predictor of current and prospective dysfunction and that failures in the assignment of social categories or attributes appear significantly increased in those with personality disorders. Thus, it has been said that such individuals possess problematic states of the self, personal representations – or “inadequate narratives” – and poor self-regulatory strategies: phenomena also linked to the problematic narcissism that many psychological theories postulate.

Regarding nosography , they proposed a reduction in the number of disorders – including a narrative description of the types – and a dimensional evaluation of the degree to which the patient resembles each of them. They justified these decisions by the excessive comorbidity between the old categories, the limited validity of some, the arbitrary thresholds established, and the instability of the characteristics evaluated for the diagnosis. Regarding the domains and facets , they argued that its implementation would solve the problem of comorbidity and the overlapping of criteria, since it offers a complete characterization of the individual personality and explains the similarities or differences between people. The proposed assessment recognizes the existence of a continuity between normality and pathology, and its potential usefulness was postulated even when the existence of a PD is not verified.

Third, the domains – with some modifications – are explicitly inspired by the negative pole of each of the factors commonly known as the Big Five.

Finally, regarding the new general criteria, they indicated that a personality disorder cannot be defined only by extreme positions in certain domains but also implies a disorganization of the personality and a significant difficulty in developing the important aspects for an adaptive functioning, oriented both to itself and to others (see Table 37.1).

Limitations and Axioms Implied in Dimensional Perspectives

Although the dimensional approaches seem to overcome most of the difficulties attributable to the categorical approach, it is necessary to consider theoretical and methodological aspects that historically outlined some characteristics. In the first place, the term “dimensional” has been used to describe a large number of approaches and heterogeneous modalities aimed at quantifying personality pathologies. Thus, according to Trull and Durret [2], the simplest meaning refers to the practice of quantifying the levels of presence-absence of diagnostic criteria, independently of the nosography that is applied. Examples of this trend are the prototype models of Oldham and Skodol [6] and Westen and Shedler [7].

A second definition consists of factorially identifying the traits underlying certain PD constructs: the 18-dimensional model of Livesley [8] and the 12-dimensional model of Clark [9] are examples of this perspective. Finally, there are approaches that transcend the strictly psychiatric-psychological constructs and integrate psychometric, neurobiological knowledge, etc: Cloninger’s Seven Factors model [10] and the Big Five Factors model are the main exponents of this perspective at present.

The Model of the Seven Factors

Cloninger describes temperament as the individual’s ability to perceive and respond to sensory stimuli, citing a large burden of genetic inheritance [10]. The combination between temperamental variables, subsequent learning, and their interaction with environmental factors generates the expansion of their characteristics; it allows phenotypicity to distance itself from the inheritance and shapes the self as the combination of temperament and character. These two interact and mutually modulate through the propositional and procedural systems allowing learning that would render the hereditary neurobiological structure. It could be argued that Cloninger’s model emphasizes the integrative character of all the components of behavior, admitting the genetic basis as the foundation of some personality traits, as well as the importance of environmental structures and the individual interpretations of them.

The Model of the Big Five Factors

Since the 1980s, innumerable evidence has been gathered showing that the aspects affected by the main classical dimensional theories can be precisely grouped into five main factors [11,12,13,14], one of whose numerous denominations can be detailed as follows: I, extraversion/introversion; II, pleasantness/hostility; III, responsibility; IV, emotional stability; and V, culture intelligence. Despite the favorable findings, limitations derived from at least two sources cannot be ignored: their foundation in the so-called lexical hypothesis and the characteristics inherent to factorial analyses.

On the “Lexical Hypothesis”

The model of the Big Five Factors is an heir of the lexical paradigm. It argues that the human sense or interest is codified or represented in language. The latter could thus be understood as a sedimentary deposit of people’s observations, in which the necessary terms would be found to define the main characteristics of the human personality. In a critical review, Richaud de Minzi [15] noted that the current consensus on the existence of five superfactors can only be understood from a historical perspective. Thus, she indicated that Allport and Odbert [16], influenced by the interest of Germans Klages [17] and Baumgarten [18] on the analysis of language as a way of knowing the human personality, provided the first list of 4504 names ascribable to the determinant, stable, and consistent tendencies of the adjustment of the individual to his environment.

Later, Cattell [20,21,21] gradually revised the original list, finally arriving at a set of 12, using a factor analysis limited by the statistical resources of his time. Tupes and Cristal [22], for the first time, attributed reliability and recurrence to a set of five factors, although their work was not free of questionable statistical choices. For example, the synonymy between terms was not considered as a possible semantic explanation of their confluence. Although the “lexical hypothesis” – whose influence is often omitted – is attractive, it has not been proven. In the words of Mc. Rae and Costa:

No one could suppose that an analysis of common terms for parts of the body would provide an adequate basis for the science of anatomy. Why should personality be different? [23]

About Factor Analysis

The use of factor analysis involves a number of decisions that may condition the fate of the results of a study [15]. The first one is the set of variables that goes under evaluation, whose structuring “prefixes” initially how many and which factors will be found. Thus, their grouping may be due to semantic and conceptual issues and not necessarily linked to the underlying structure of the personality. This condition is a reason for questioning the so-called universality [16] of the five-factor model, since it is not part of a previous psychological theory but rather derives remotely – as previously indicated – from Cattell’s own list [14].

The Use of Self-Reports and the Conscious Assessment of Traits

Although the evaluation practices suggested by the authors of the different dimensional models are heterogeneous, most of them include the use of self-administered questionnaires, based on comparative, simple, general, and vague statements [24]. Among the most recognized are the MMPI-II of Hathaway and McKinley [25]; the NEO-PI-R of Costa and McRae [26]; the MCMI-III of Millon, Davis, and Grossman [27]; the 16-PF of Cattell of Eber and Tatsuoka [28]; the EPQ of Eysenck and Eysenck [29]; and the PANAS of Watson of Clark and Tellegen [30].

The Minnesota Multifaceted Personality Inventory [25] from its origins in the 1940s is one of the most widely used psychological tests worldwide due to its high standards of reliability and validity. The authors created the technique with an empirical-rational approach, comparing analysis of stories, attitudes, and ideas frequent in different patients with the characteristics exposed in the nosology of Kraepelin. Its adaptation to the Argentinian context in 1989 made it possible to exponentially increase its use, resulting in an indispensable technique in the clinical and legal spheres. Through 567 items of dichotomous response, the evaluated construct is pathological personality, understood as those lasting characteristics of a subject that are determinants of their behavior. The technique has three validity scales and nine clinical scales that allow obtaining information about different personality traits. The intrinsic difficulties associated to the instrument are related to its long extension and the outdated theoretical criteria and terms.

The NEO-PI-R test by Costa and McRae [26] is a self-conscious instrument , presented as a nonexclusive clinical test, suggesting its use in the educational and organizational context. It has the model of the Big Five as a theoretical basis and explicitly excludes standards from the rest of the literature concerned. One of the admitted weaknesses of the instrument is its low internal consistency. Some authors mention the natural impossibility that presents for retesting, for inter-rater observation, and even for longitudinal follow-up [31].

The MCMI-III instrument of Millon, Davis, and Grossman [27] is oriented with the diagnostic system ratified in the editions of DSM-4 and DSM-5 grouping the categories in the axes I towards the clinical disorders and II towards the disorders of the personality and mental retardation. Through a scoring system, it maintains a scale of values that indicate the severity of psychopathology.

Some criticisms about these instruments are focused on their limited contribution to the symptomatological description of depressive disorders and on methodological errors presented by the major depression and anxiety disorder scales: as described, they show a considerable number of false positives and false negatives. A professional review of each result is necessary [32]. The lack of literature regarding its methodological validity was also highlighted, with the lack of interevaluation cross-sectional studies or analysis of internal coherence regarding collateral data or forensic analysis. Some authors [33] consider the validation of anxiety scales to be poor, making it difficult to classify their severity and even to discriminate against depressive symptoms.

Cattell’s 16PF test [28] consists of an evaluative questionnaire of 16 personality traits called first-order factors which are identified as affectivity, reasoning, stability, dominance, impulsivity, group conformity, daring, sensitivity, suspicion, imagination, cunning, guilt, rebellion, self-sufficiency, self-control, and tension. All individuals could be described based on these traits, and the difference in the extent of each of them would confirm the personality. Some of the questioning of the proposed instrument focuses on the critique of Cattell’s model, which, among other things, subtracts from the semantic character of language and makes it prone to misunderstandings or coherence problems. On the other hand, authors like Nowakowska [34] question that Cattell has not been exhaustive enough in the verification of his hypotheses about the personality before elaborating the instrument to analyze its features.

The personality questionnaire of Eysenck and Eysenck [29] called EPQ is used in a self-administered form, answering items in a dichotomous way. It results in a description of the personality that represents the combination of its intervening factors that can be classified in a double axis of four points: stability-neuroticism, extroversion-introversion, normality-psychoticism, and lability-veracity.

Basing his theory mainly on the model of the Big Five, many of the criticisms are made about the supposed anachronism of the model or the low methodological reliability, despite having obtained coefficients greater than 0.7 in internal coherence and retest. However, the same authors recognized certain psychometric weaknesses and reformulated the scales by adjusting the arithmetic mean. It has also been pointed out that the scales are not intercultural, so they are ineffective in certain social contexts and that, on the other hand, although the use of the first version of the test is discouraged, it is still the most used in the world. It can be inferred a lack of knowledge of their reviews or a considerable difference of values between different countries [35].

Finally, the PANAS affectivity scale elaborated by Watson, Clark, and Tellegen [30] evaluates positive and negative affectivity through 20 items with a Likert-like response. It supports its construct in the hypothesis that the characteristics of extroversion in personality are linked to positive affectivity and introversion or neuroticism to negative affectivity. Based on this postulate, depression and anxiety could be discerned, as well as the correlation of the values contributed by this scale with respect to other personality evaluations validating their reliability [36, 37].

Although this instrument has found some correlation with scales of other complexity, some authors argue that the dimensional analysis within the factorial construct tends to limit the expression of some characteristics of the subject, showing that negative affectivity can be quickly related to a determined set of symptoms. This tendency cannot be verified in terms of positive affectivity and anxiety symptoms or their consequences on personality traits [38].

All the aforementioned instruments can contribute to the evaluation of the level of prototypicity and the severity of a disorder, but this does not eliminate the need for a qualitative clinical assessment of the structure and functioning of the personality, as well as specific subjective and interpersonal difficulties. In this sense, the perspective of Westen et al. [39] makes an important contribution, since it emphasizes the approach by prototypes and proposes a protocol for recording the observations of clinicians [7] that is not limited only to the patient’s conscious self-perceptions. In this way, intrapsychic and dynamic aspects of the personality [1] are included.

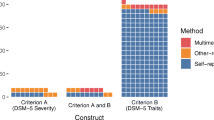

In the alternative system of the DSM-5 , the clinician is in charge of collecting the information to perform a characterization by prototypes, domains, and facets. In any case, it would be important to consider which techniques were applied in the studies that have provided their theoretical foundations.

The Differentiation Between Health and Pathology

From a dimensional perspective, to define whether a personality has pathological characteristics, it is necessary to have “thresholds” or “cutoff points” [40]. Even when population statistical indicators can be established, any limit imposed is in some sense arbitrary – we remember that Skodol [5] admits continuity between normality and pathology – and may be useless for the actual treatment. The definitions that only consider the “universal” aspects bring with them the risk of a partial clinical judgment that obscures the particularities of the individual case.

As McAdams [24] warned, nuclear features indicate very little about the characteristics that differentiate people and motivate their actions: these aspects seem unattractive to the methodologies usually used in dimensional models.

Synthesis and Discussion

A Dimensional System Could Optimize Existing Nosography?

Given that the categorical constructs of the DSM have shown little empirical validity, it is reasonable to suppose that the dimensional perspective would make the definition of the PD more objective. However, the high use of self-administered questionnaires for the collection of information fosters a bias towards people’s conscious self-assessments, while the factorial techniques underlying the theories generate reasonable doubts about their construction and validity. Likewise, such limitations do not invalidate the usefulness of the dimensional approach, although it is reasonable to note that without meticulous and systematized clinical observations, a vague, trivial, and atheoretical nosography could be reached, providing limited usefulness to understand the genesis and evolution of the pathologies. In this sense, we consider remarkable the proposals that involve registration protocols for professionals, as well as contrast methodologies with standard cases.

The construction of an optimal nosography should cover the currently existing taxonomy in the clinical and research areas and encourage the revision of its categories. Otherwise, the use of overlapped parameters that make it difficult to trace the evolution and treatment could be insisted upon.

A Dimensional System Would Enrich the Existing Theories?

Part of the resistance to the adoption of a dimensional methodology in the clinical context can be ascribed to the need to maintain continuity with theoretical constructs that have been shaped and perfected over long periods of time. All the theories concerning the structure of the personality are subject to criticism, but they also integrate valuable postulates and synthesize an effort of several centuries dedicated to the understanding of key aspects of human existence. In this sense, we consider that the revisions that are carried out from now on should contribute to a more complete understanding of the conditions that affect the development of the personality. Therefore, they should not be based on a mere statistical pragmatism that gives apparent objectivity to the systems we adopt for the study and the clinic.

The theoretical reformulations must not be exempt from scientific rigor and should incorporate the new contributions that neurobiology and cognitive psychology have made in this field. Every scientific model must have the precision to account for the observable and flexibility to explain the data that future advances may obtain. The arrival of determining classifications should not be – a priori – an obstacle to appreciate the singularities of each case.

A Dimensional System Would Simplify Clinical Decisions?

Among the aspects mentioned above, two are contradictory to each other: although theoretically the use of a dimensional system would clarify the limits between normality and pathology by focusing on dimensions attributable to all people, it would maintain the need to establish certain boundaries or cutoff points. In this sense, it may be pertinent that clinical decisions were based on the specific impact that the identified characteristics have on the patient’s daily life: the difference between condition and health should be based on the presence of unwanted or disabling manifestations for the patient’s personal and social development.

It is at this point that clinical expertise must be present and determine the process to be followed with each case. An important aspect to consider is the frequent egosintonicity of the symptoms: the self-perception of the patient would not in all cases be sufficient for an objective analysis, for which additional sources of information must be required. Therefore, caution should be exercised when making estimates regarding the intensity of a condition or the need for its treatment by the mere application of statistical procedures. At this point, we mention the need to review the tests of external validity and internal coherence of some instruments commonly used for diagnosis.

The following table outlines the route proposed by this review. Finally, possible future debates are opened, and some considerations are recommended to propitiate this path (Table 37.2).

Conclusions

The consideration of the dimensional perspective involves important contributions for the diagnosis and treatment of PDs. Although it maintains some difficulties – especially about therapeutic frontiers – it allows a more detailed description of the problems and could contribute to the definition of the relevant aspects of personal history and development, in which deepening is key to deciding therapeutic modalities. The comparison with prototypes is also a valuable resource for clinical training.

We consider that the conditions of this transition reflect the current effort to encompass the profound complexity of the human personality and to reconcile it as much as possible with the scientific refinement that is expected from any discipline. There are several personality theories currently recognized. It is unlikely that its synthesis will be reached: they start from different assumptions and have been built using unequal technical procedures. Perhaps this diversity contributes to maintaining high levels of effort that result, little by little, in a better approach to the ailments.

References

Esbec E, Echeburúa E. The reformulation of the PT in the DSM-V. Span Acts Psychiatry. 2011;39(1):1–11.

Trull TJ, Durrett CA. Categorical and dimensional models of personality disorder. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:355–80. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144009.

American Psychiatric Association. Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5®. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Pub; 2014.

Krueger RF, Eaton NR. Personality traits and the classification of mental disorders: toward a more complete integration in DSM–5 and an empirical model of psychopathology. Personal Disord Theory Res Treat. 2010;1(2):97.

Skodol AE, Clark LA, Bender DS, Krueger RF, Morey LC, Verheul R, Oldham JM. Proposed changes in personality and personality disorder assessment and diagnosis for DSM-5 Part I: description and rationale. Personal Disord Theory Res Treat. 2011;2(1):4.

Oldham JM, Skodol AE. Charting the future of Axis II. J Personal Disord. 2000;14(1):17.

Westen D, Shedler JA. Prototype matching approach to diagnosing personality disorders: toward DSM-V. J Personal Disord. 2000;14(2):109–26.

Livesley WJ. Trait and behavioral prototypes of personality disorder. Am J Psychiatr. 1986;143(6):728–32.

Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S. Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103(1):103.

Cloninger CR. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:573–88. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180093014.

Suzuki T, Samuel DB, Pahlen S, Krueger RF. DSM-5 alternative personality disorder model traits as maladaptive extreme variants of the five-factor model: an item-response theory analysis. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015;124(2):343.

De Raad B, Mlacic B. Big five factor model, theory and structure. In: International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences, vol. 2. 2nd ed: London: Elsevier; 2015.

Allen TA, De Young CG. In: Widiger TA, editor. Personality neuroscience and the five-factor model. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015.

Digman JM. Personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model. Annu Rev Psychol. 1990;41(1):417–40.

Richaud de Minzi C. Una revision crítica del enfoque lexicográfico y del Modelo de Cinco Grandes Factores. Rev Psicol de la PUCP. 2002;20(1):5.

Allport GW, Odbert HS. Trait names: a psycho-lexical study. Psychol Monogr. 1936;47(1):i.

Widiger TA, Trull TJ. Plate tectonics in the classification of personality disorder: shifting to a dimensional model. Am Psychol. 2007;62(2):71.

Klages L. The science of character (Translated 1932). London: Allen and Unwin. McCrae, R. R.; 1926.

Cattell RB. The description of personality: basic traits resolved into clusters. J Abnorm Soc Psychol. 1943;38(4):476–506. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054116.

Cattell RB. The description of personality: principles and findings in a factor analysis. Am J Psychol. 1945;58:69–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/1417576.

Cattell RB. Confirmation and clarification of primary personality factors. Psychometrika. 1947;12:197–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02289253.

Tupes EC, Cristal RC. Recurrent personality factors based on trait ratings. J Pers. 1992;60:225–51.

McCrae RR, Costa PT. Openness to experience. In: Hogan R, Jones WH, editors. Perspectives in personality: theory, measurement, and interpersonal dynamics, vol. 1. Greenwich: JA1 Press; 1985.

McAdams DP. The five-factor model in personality: a critical appraisal. J Pers. 1992;60(2):329–61.

Butcher JN, Dahlstrom WG, Graham JR, Tellegen A, Kaemmer B. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2): manual for administration and scoring. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 1989.

Costa PT, MacCrae RR. Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO FFI): professional manual. Psychol Assess Resour. 1992.

Millon T, Millon C, Davis RD, Grossman S. Millon clinical multiaxial inventory-III (MCMI-III): manual. San Antonio: Pearson/PsychCorp; 2009.

Cattell RB, Eber HW, Tatsuoka MM. Handbook for the sixteen personality factor questionnaire (16 PF): in clinical, educational, industrial, and research psychology, for use with all forms of the test. Institute for Personality and Ability Testing; 1970.

Eysenck HJ, Eysenck SBG. Manual for the eysenck personality questionnaire:(EPQ-R adult). San Diego: Educational Industrial Testing Service; 1994.

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063.

McCrae R, Kurtz J, Yamagata S, Terracciano A. Internal consistency, retest reliability, and their implications for personality scale validity. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15(1):28–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310366253.

Otiniano Campos F. Validity of construction and diagnostic efficacy of the scales of major depression and anxiety disorder of the millon multiaxial clinical inventory III (MCMI-III). Doctoral thesis not published. Lima. Catholic University of Peru; 2012. Available from: http://tesis.pucp.edu.pe/repositorio/bitstream/handle/123456789/1479/OTINIANO_CAMPOS_FIORELLA_VALIDEZ_CONSTRUCTO.pdf?sequence=1

Saulsman LM. Depression, anxiety, and the MCMI–III: construct validity and diagnostic efficiency. J Pers Assess. 2011;93(1):76–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.528481.

Nowakowska M. Perception of questions and variability of answers. J Behav Sci. 1973;18(2):99–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830180203.

Zambrano CR. Systematic review of the Eysenck personality questionnaire (EPQ). J Psychol. 2011;17(2):147–55.

Crawford JR, Henry JD. The positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004;43(Pt 3):245–65. https://doi.org/10.1348/0144665031752934.

Robles García R, Páez F. Study of Spanish translation and psychometric properities of the positive and negative affect scales (PANAS). Salud Ment. 2003;26(1):69–75.

Kotov R, Watson D, Robles JP, Schmidt NB. Personality traits and anxiety symptoms: the multilevel trait predictor model. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(7):1485–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.11.011.

Westen D, Defife JA, Bradley B, Hilsenroth MJ. Prototype personality diagnosis in clinical practice: a viable alternative for DSM-V and ICD-11. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2010;41(6):482–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021555.

Trull T, Widiger TA. Dimensional models of personality: the five-factor model and the DSM-5. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;15(2):135–46.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Alfonso, G. et al. (2021). The Transition to a Dimensional System for Personality Disorders: Main Advances and Limitations. In: Gargiulo, P.Á., Mesones Arroyo, H.L. (eds) Psychiatry and Neuroscience Update. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61721-9_37

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61721-9_37

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-61720-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-61721-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)