Abstract

Schwartz Centre Rounds (Rounds), which originated in Boston, USA, are organisation-wide forums for healthcare staff which prompt reflection and discussion of the emotional, social or ethical challenges of healthcare work. Drawing on data from our UK National evaluation of Rounds we outline the unique features of Rounds as an organisational intervention, highlighting their differences to other wellbeing interventions and explain how Rounds work to influence organisational change and patient safety. As Rounds are open to all staff they are able to shine a spotlight on hidden organisational roles and staff groups, sparking greater insight and understanding of what peoples’ roles involve, resulting in reported reduced isolation and staff connection through sharing similar experiences. Rounds can help staff see and connect with the bigger picture of how the organisation functions helping to develop organisational cohesiveness and connectedness to the organisational mission and values and provide a space to process patient cases and learn from mistakes. Rounds can provide a counter-cultural space, allowing opportunities for staff to process and reflect upon difficult and satisfying aspects of their work as individuals, within teams and as an organisation. We reflect upon the challenges of implementing and sustaining Rounds including their evaluation and measuring organisational change resulting from Rounds provision.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This chapter draws upon data from a UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) commissioned national evaluation of Schwartz Center Rounds®(Rounds) in the UK which aimed to examine how, in which contexts and for whom, participation in Rounds affects staff wellbeing at work, social support for staff and improved relationships between staff and patients (Maben, Taylor, et al., 2018). Rounds originated in Boston, USA in 1994 and were introduced to the UK in 2009 and Australia in 2017. They are now run in over 420 healthcare organisations in the US, over 200 healthcare organisations in the UK and Ireland and approximately 10 organisations respectively in Canada and Australia and New Zealand (Maben, Taylor, et al., 2018).

Rounds were inspired by the experiences of a 39-year old healthcare lawyer, Kenneth Schwartz, who when terminally ill with lung cancer wrote in the Boston Globe in 1995 (Schwartz, 1995) that “small acts of kindness made the unbearable bearable” noting the importance of caregivers showing empathy and engaging with him as a person. He noted some caregivers could do this and others couldn’t and even those that did, could not do it every day. This led him to consider what it was like to work in an environment where people were regularly dying—what was the toll on healthcare staff and how could they be supported to remain engaged and compassionate? Before his death, he set up the Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care (SCCC) as a not-for-profit organisation where Rounds were developed and then implemented in North America over 20 years ago. Rounds were implemented in the UK, via the Point of Care FoundationFootnote 1 (PoCF), who have held the license with SCCC to run Rounds in the UK since 2009.

Rounds provide a regular, usually monthly, forum where structured time and a safe, confidential space is offered for staff to get together to discuss and share the emotional, social or ethical challenges of caring for patients and families. They are organisation-wide forums, open to all staff (clinical and non-clinical)—implicitly recognising that all staff within healthcare organisations are integral to the provision of compassionate patient care. They are intended to help improve staff wellbeing, effectiveness of communication and work engagement, and ultimately patient care. Thus the purpose of Rounds is to support staff and enhance their ability to provide empathic and compassionate care.

Each Round usually lasts for one hour and begins with a pre-prepared multidisciplinary panel presentation of a patient case by the team who cared for the patient, or a set of different stories based around a common theme. Up to four panellists each describe the impact on them of the difficult, demanding or satisfying aspects of the situation and the topic is then opened to the audience for group reflection and discussion. Trained facilitators (usually a senior doctor and psychosocial practitioner, e.g. a psychologist or social worker) then guide discussion of emerging themes and issues, allowing time and space for the audience to comment and/or reflect on similar experiences they may have had. Rounds are typically organised and managed by a steering group and championed by a senior doctor/clinician. The role of the steering group is to support the facilitator and clinical lead to source stories that will resonate with the wider organisation and its staff, and support panellists to tell their stories safely and succinctly. Consequently, staff with roles that give them organisational or departmental/faculty perspectives are often approached to be members. Attendance is voluntary and staff attend as many or as few Rounds as they are able. Food is provided, usually before the Round. Rounds take place during work hours and organisations typically experiment with the timing of Rounds (e.g. early morning to capture those finishing night shifts, lunchtimes, afternoons) in order to allow different types and members of staff to attend.

There had been few evaluations of Rounds prior to the study we report in this chapter (<15 empirical studies to date), though evidence from evaluations conducted in the USA and UK suggests that those attending Rounds perceive benefits to their wellbeing (e.g. reduced stress and improved ability to cope with psychosocial demands at work) and improved relationships with colleagues (e.g. better teamwork), and that Rounds attendance may lead to more empathic and compassionate patient care, and wider changes to institutional culture (Goodrich, 2012; Lown & Manning, 2010). The evidence base mostly consists of weak study designs including lack of control groups, and non-validated measures (e.g. self-report views/satisfaction with Rounds) (Taylor, Xyrichis, Leamy, Reynolds, & Maben, 2018). Only one previous study has included non-attender control group comparisons (Reed, Cullen, Gannon, Knight, & Todd, 2015). Evidence shows Rounds to be highly valued by attenders and most studies reported positive impact on ‘self’ (e.g. improved wellbeing, improved ability to cope with emotional difficulties at work, self-reflection/validation of experiences) (Taylor et al., 2018).

2 Unique Features of Rounds Compared to Other Wellbeing Interventions

Healthcare organisations that wish to address the wellbeing needs of their workforce are faced with a plethora of interventions to choose from including those designed to reduce stress (e.g. stress management, relaxation, mindfulness programmes) through to those designed to restructure working conditions (e.g. flexible working policies). One way in which wellbeing interventions have been categorised is according to their intended purpose: primary (reduce/eliminate stressors); secondary (reducing individuals perceptions of or reactions to stressors); or tertiary (treating or ‘rehabilitating’ those who have poor wellbeing and intended scope (aimed at individuals, teams or whole organisations) (DeFrank & Cooper, 1987; deJonge & Dollard, 2002; Tetrick & Quick, 2011), and numerous authors have called for a “systems approach” to tackling poor wellbeing at work, that includes interventions addressing both individual and environmental/structural factors, and for preventing, reducing and treating poor wellbeing (Boorman, 2009; Goetzel & Pronk, 2010). However, systematic reviews of healthcare workforce wellbeing interventions have repeatedly highlighted the lack of interventions targeting organisational impact or change, with most targeting the individual (e.g. stress management, mindfulness courses etc.) (Graveling, Crawford, Cowie, Amati, & Vohra, 2008; Marine, Ruotsalainen, Serra, & Verbeek, 2006; NICE, 2009; Seymour & Grove, 2005). The focus on the individual, whilst important, risks placing the onus of responsibility for wellbeing solely on the individual (‘blaming’ them that they are not coping). As stated by Chambers and Maxwell over 20 years ago in an editorial in the British Medical Journal, but relevant to all healthcare professionals, “if the job is making doctors sick, why not fix the job rather than the doctors”. (Chambers & Maxwell, 1996).

Rounds are a rare example of an intervention that targets wellbeing at an organisational level. They offer many of the same resources as other wellbeing interventions, such as a safe and confidential space for reflection and open, honest communication. Such features are key to many interventions designed to support healthcare workers manage the impact of their work on their wellbeing, including Critical Incident Stress Debriefing, After Action Reviews; and Clinical Supervision. However, a key purpose of these other interventions is to ‘problem solve’ or action plan: to use the patient case or event as the purpose of the discussion to challenge, explore and discuss what happened and what could be done (or felt) differently (Taylor et al., 2018). However, Rounds differ from these other types of reflective practice interventions, as solving problems or focusing upon the clinical aspects of patient care is not the intention, rather the focus is on the impact on staff of providing care for patients often in challenging emotional social or ethical circumstances, not the clinical case itself (Maben, Taylor, et al., 2018). Instead the stories (or cases) shared within a Schwartz Round are instead intended as trigger stories, to resonate with the audience and encourage reflection about their thoughts and feelings. Indeed they are prepared prior to the Round (in panel preparation, with the facilitator and ideally with the other panellists too) so that the essence of their stories and in particular those aspects that will most resonate with the audience are prioritised in the story told in the Round itself. The facilitator is trained to intervene if the audience attempt to question those sharing their stories, or to problem solve in relation to their story, instead directing the audience to reflect and share the resonance it has with them. This is important to ensure the psychological safety of those sharing their stories in Rounds (see below), as unlike these other interventions, Rounds are open to all staff, meaning the composition of the audience/group is different in every Round. This differs from the closed (or ‘invited’) membership of other interventions (such as Balint Groups or Critical Incident Stress Debriefing) that includes only staff involved in an incident or event or who have a relationship with each other for other purposes. The sharing of the ‘story’ or ‘case’ thereby has a very different purpose in Rounds compared to other interventions.

Schwartz Rounds are most similar to group interventions such as Balint Groups and Reflective Practice Groups, both of which are also designed to be ongoing programmes providing facilitated forums for staff to share experiences of delivering patient care, and have as core features the ability to offer and receive peer support in safe confidential environments. However, both have “closed” (e.g. invited) membership, are often uni-disciplinary (e.g. Balint Groups originated in primary care for General Practitioners), and thereby are not open to all staff in an organisation. Nor do they offer the opportunity for ‘silent’ participation—there would be an expectation that all members of the group would contribute and participate.

The size of the evidence base for comparative alternative interventions to Rounds is variable, ranging from being very sparse for some (less than five empirical evaluations within healthcare for Psychosocial Intervention Training, Peer-supported storytelling, Critical Incident Stress Debriefing and Caregiver Support Programme), with the most evidence available for Clinical Supervision and Balint Groups (Taylor et al., 2018). Akin to Schwartz Rounds, much of the evidence is low quality in relation to study design (e.g. cross-sectional studies; post-interventional evaluations lacking control comparisons); sampling (e.g. non-probability and small samples; many focused only on nursing workforce); used non validated outcome measures; and were heterogenous in relation to aims, content and format of interventions. However, across most interventions there is limited evidence of beneficial impact to the individual healthcare workers, in their relationships with others, and to the wider organisation, as found with Schwartz Rounds (Taylor et al., 2018).

Therefore key features that are unique to Schwartz Rounds, and that lead to them having unique and specific outcomes (see section below) include (a) that they are an ongoing intervention that is open to all staff in an organisation: they do not require sign-up or membership, and all staff are welcome—regardless of their seniority or role, including those in non-clinical roles); (b) they provide a space where there is no expectation for contribution (silent reflection is valued and acceptable); (c) where storytelling (of an event or patient case) is used as a vehicle for resonance and reflection in others rather than as an end in itself; and (d) their central purpose is to focus on the impact of caregiving on the caregivers themselves: other interventions may do this sometimes but not as a key feature.

3 The Research

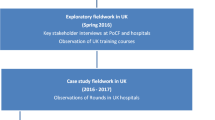

We conducted a realist-informed mixed methods evaluation of Schwartz Rounds with data collected in 2015 and 2016. Realist Evaluation is a theory-driven approach to evaluation that involves identifying causal explanations of how Rounds work, for whom, and under which circumstances. Using this methodology allowed us to take account of the complexity of the intervention and its interaction with the organisational settings of our case study sites. The aim is therefore to understand the effect that Context (C) has on how an intervention works, in relation to enhancing or decreasing the effects of Mechanisms (M) in order to produce outcomes (O): C + M = O. Following an initial mapping phase where we undertook telephone interviews with Rounds leads and facilitators (45/76 59%) and surveyed all sites regarding implementation and resources (41/76 54%) (Robert et al., 2017) we sampled nine case study sites for in-depth realist evaluation using observation and interview methods. In addition, and due to the perceived need to also provide data on ‘hard’ outcomes from Rounds attendance, we sampled ten case study sites to participate in a longitudinal staff survey. Six sites participated in both.

3.1 Longitudinal Staff Survey

In ten sites (acute/mental health/community Trusts and hospices), following a pilot study in two sites, a staff survey was conducted with staff who had never attended Rounds, recruited either immediately prior to the start of a Round, or via a random sample of staff through an online survey. All were followed up 8 months later, resulting in completed surveys at both time points by 256 staff who had attended at least one Round by the time of the follow-up (51 classified as regular attenders, having attended at least half of the Rounds that had run in their site between baseline and follow-up surveys), and 233 who were non-attenders (controls, e.g. had never attended Rounds at Baseline or when re-assessed at follow-up). This longitudinal staff survey was administered to determine if Rounds have an impact on work engagement, wellbeing, as well as empathy, compassion and reflective practice. The questionnaire included validated measures of work engagement, psychological wellbeing, self-reflection, empathy, compassion, peer support and organisational climate for support, and questions about absenteeism and views on Rounds (see Maben, Taylor, et al., 2018 for measures). The primary analysis compared regular attenders (defined as attending at least half of the Rounds held in the organisation in the 8 month period, n = 51) to non-attenders (n = 233); supplementary analysis examined the effects of attending different numbers of Rounds (thereby including the intermediary group of those that attended fewer than half of the Rounds available at their site).

3.2 Organisational Case Studies: Realist Evaluation

Concurrently, organisational case studies were undertaken in nine sites (acute/mental health/community Trusts and hospices: six were also survey sites). These were purposively sampled from all Rounds providers to provide maximum variation (such as size of institution, established and new Rounds and early and late adopters). The purpose was to understand (1) the mechanisms by which Rounds ‘work’ and result in outcomes and ripple effects regarding staff wellbeing and social support and outcomes for patients; and (2) staff experiences of attending, presenting at and facilitating Rounds.

We observed 42 Rounds, 29 panel preparation meetings and 28 steering group meetings and we undertook a large number of interviews with clinical leads, facilitators, panellists, and members of steering groups, audiences, organisation Boards and regular, irregular and non-attenders across the nine case studies (n = 177). Data were managed using NVivo, and analysed thematically to identify staff experiences and contextual variation of Rounds. Data were also analysed concurrently, using realist evaluation methods (Manzano, 2016; Pawson & Tilley, 1997), to identify causal explanations for how Rounds work (articulated as Context + Mechanism = Outcome (CMO) configurations) which were then tested and refined in subsequent interviews (Manzano, 2016) and two focus groups with Rounds mentors and key Point of Care Foundation (PoCF) stakeholders (Maben, Taylor, et al., 2018). This in-depth iterative process of simultaneous collection and analysis of data resulted in the development of nine interlinked programme theories explaining how and why Rounds produce outcomes:

-

(i)

The importance of trust, psychological safety and containment;

-

(ii)

Group interaction enhances reflection and sharing of stories;

-

(iii)

Rounds provide a counter-cultural space for staff;

-

(iv)

Rounds create an environment where staff are willing to self-disclose;

-

(v)

Story-telling provides a vehicle for staff to talk about their experiences at work;

-

(vi)

Staff role modelling vulnerability, courage and bravery reveals their humanity

-

(vii)

Stories provide greater context to patient and staff experiences;

-

(viii)

Stories shine a spotlight on hidden stories and roles; and

-

(ix)

Rounds facilitate experiences to be shared through storytelling that resonate and trigger reflection (Maben, Taylor, et al., 2018).

4 How Rounds Work to Produce Outcomes

The use of realist evaluation methods in our organisational case studies identified how Rounds work to produce their outcomes by influencing individuals, teams and organisational change to impact on patient care (Maben, Taylor, et al., 2018).

Overall, through analysis of our observation of Rounds and interviews with Rounds participants, we identified that good facilitation and the creation of a safe space supported staff to disclose stories revealing difficult, demanding and satisfying aspects of their work. When staff showed their human and vulnerable side it broke down barriers between them, and created a level playing field for all staff. The group interaction and hearing multiple perspectives created a recognition of shared experiences and feelings, and provided greater insights into patient, carer and staff behaviours. Rounds shone a spotlight on hidden organisational stories and roles, and provided opportunities for reflection and resonance so staff could make sense of their experiences at work. Interviewees described Rounds as interesting, engaging and a source of support, valuing the opportunity to learn more about their colleagues, understand their perspectives and motivations and reflect and process work challenges. Rounds reportedly increased understanding, empathy and tolerance towards colleagues and patients. A few Rounds attenders interviewed described feelings of negativity associated with Rounds, including questioning the purpose of unearthing feelings of sadness, anger and frustration in work time and others found witnessing the anguish of others uncomfortable. Asked about ‘unsuccessful’ Rounds some suggested poor attendance, prolonged silences, strained discussions and perhaps a lack of personal interest in the Round topic defined whether they felt the Round was successful or not. Yet others felt silence was an important and unique aspect of Rounds that supported contemplation, and provided an alternative to their usual busy, noisy professional lives.

In-depth analysis of our interviews with clinical leads, facilitators, panellists, and members of steering groups and audiences across the nine case studies (n = 177) enabled us to identify the self-reported impacts of Rounds. Over time, Rounds have a cumulative effect (as illustrated by the arrows in Fig. 17.1). For example, a Schwartz-savvy audience develops (Rounds attenders who really understand the purpose of Rounds, know and follow the explicit and implicit rules of how to contribute appropriately and support each other in a non-judgemental way) who can support the facilitator to ensure safety and containment, build trust and a supportive community. Staff who attended Rounds reported attendance having a beneficial impact on them as an individual, on relationships with colleagues, on relationships and encounters with patients and on the organisation and its culture. Staff reported having increased empathy and compassion for colleagues and patients; reduced feelings of isolation; and improved teamwork and communication (see Table 17.1).

Key components of Rounds that result in impact. Adapted from Understanding Schwartz Rounds: Findings from a National Evaluation film: https://youtu.be/C34ygCIdjCo

Our survey of Rounds attenders and non-attender control groups across the ten case study organisations (500 responses at time points 1 and 2) found a significant reduction in poor psychological wellbeing of staff as a result of attending Rounds. There was no significant impact of Rounds attendance on any of the other outcomes measured in the survey.

At the beginning of our study, a third of all staff in our survey (n = 32%) reported poor psychological wellbeing before attending any Rounds. Staff who did not attend any Rounds during the study (and who had never attended Rounds before: our control group) reported poorer baseline psychological wellbeing (37%) compared to attenders (25%), suggesting those that attend Rounds may be a self-selecting group with better well-being than non-attender peers. When we re-surveyed the same group 8 months later, there was little change in these staff who hadn’t attend Rounds (37% at baseline 34% at 8 month follow-up). However, in staff who attended Rounds, the proportion with poor psychological wellbeing had halved over the same 8 months period from 25 to 12%. The odds ratio for this effect was 0.28 (95% CI 0.08–0.98) See Figs. 17.2 and 17.3 infographics below. The difference between the two groups at baseline should be acknowledged, however (a) the analysis controlled for baseline values so the change was the focus of the analysis; (b) the higher level of ‘caseness’ was found in the non-attenders group (where we found less change over time) ruling out any regression to the mean effects; (c) the effect of Rounds attendance was not limited to this one analysis, but was consistent across a range of effects (e.g. when using different definitions of regular attendance, or comparing any attendance with non-attendance).

So how is poor psychological well-being halved in regular Rounds attenders? Our study supported Wren’s work (Wren, 2016) to suggest that Rounds offer a unique countercultural space by providing a psychologically safe contained space, where staff experience is the priority, emotional disclosure is encouraged, and staff support and listen to each other without judgement. Wren writes: “the process of Schwartz Round implementation is in many ways counter-cultural. Good Rounds shift an organisation and its workers away from their default position of urgent action, reaction and problem solving to an hour of stillness and slowness”. (Wren, 2016: page 41). This is ‘counter-cultural’ because it differs very much from the usual healthcare culture in the UK where there is a busy, hierarchical, outcome-oriented environment, where stoicism is valued and where staff are exhorted to put patients (not their own well-being) first. In this counter-cultural Rounds space, hierarchies are flattened, defences are left at the door and staff humanity is revealed, supporting other to disclose, share experiences and make themselves more open and vulnerable creating a cycle of support and facilitating greater empathy and compassion for self, other staff and ultimately patients and carers, reducing poor psychological wellbeing in staff attenders.

While Schwartz Rounds do not set out to solve problems, or produce outcomes per se, we identified examples of changes in practice such as the revision of resuscitation protocols based on Rounds discussions as well as other ripple effects such as changes in types of conversations occurring in organisations (allowing more open conversations, or more wellbeing focussed, noting links between the importance of staff wellbeing for good patient care delivery), and new support groups were reportedly set up when unmet needs were identified.

5 What Are the Challenges of Implementing, Evaluating and Sustaining Rounds?

Rounds are a complex organisational intervention, with many interacting components that work to produce the outcomes described above. Aside from the complexity inherent to all interventions that include behavioural/human interaction, Rounds are a multi-stage intervention; we identified four stages to Rounds, with the Round itself only constituting one of those stages (Fig. 17.4).

Rounds stages, with cumulative effects [reproduced with permissions from NIHR journals (Maben, Taylor, et al., 2018)]

Stage one is sourcing stories and panellists to tell the stories; stage two is preparing the panellists to tell their stories; then stage 3 is the Round itself, where staff tell their stories and the audience reflects and share further stories; then finally stage 4 is the post-Round after effects; the outcomes and ripple effects resulting from the Round and preparation for the next Round. Over time, stage four of one Round/series of Rounds, impacts upon the early stages of the next Round/Rounds to have cumulative effects and impact. This complexity in structure and process for Rounds lends itself to a variety of challenges in implementing, evaluating and sustaining Rounds.

Our evaluation highlighted key challenges relating to both the structure (personnel resources for running Rounds especially in relation to the core team: facilitators, clinical lead and administrators); and in relation to the process of running Rounds (particularly sourcing stories and panellists, preparing them adequately to ensure safety in Rounds, ensuring reach and accessibility to all staff, and evaluating and measuring outcomes from Rounds). We found that some Rounds sites were inadequately resourced either lacking administrative support or only having one facilitator. Furthermore, in many organisations the responsibility for running and sustaining Rounds rested on the shoulders of a few individuals with an apparent lack of senior organisational commitment and support.

Our key recommendations for implementing and sustaining Rounds based on findings from our evaluation (Maben, Leamy, et al., 2018) include:

-

(a)

Ensuring organisational support for Rounds: This is a key feature built into the contract required by organisations wishing to run Rounds. In the UK, the Point of Care Foundation require a letter of support from the chief executive before they will issue a licence. This support is fundamental to the success of Rounds in relation to the provision of adequate resources (see below); supporting staff to implement initiatives to enable staff to attend Rounds; and actively demonstrating shared ownership and responsibility for the sustainability of Rounds. Ideally, we recommend identifying a Board member to share responsibility with the clinical lead and facilitator to implement and sustain Rounds.

-

(b)

Ensuring adequate resources for Rounds: this includes the personnel required to run Rounds (appropriate amounts of time in job plans for facilitators, clinical leads and administrators; funding for facilitator training for sufficient numbers of facilitators); any room and publicity costs; and the provision of food at each Round (which is a contractual requirement). It is important to ensure that facilitators have appropriate skills to safely run Rounds (e.g. prior group facilitation knowledge, experience and skills in identifying and managing distress), and our data suggest that to keep Rounds psychologically safe there should always be at least two facilitators in each Round.

-

(c)

Ensuring adequate support for facilitators and clinical leads: Running and sustaining Rounds can place considerable strain and burden on facilitators and clinical leads, both in terms of the sheer time it can take to organise and run Rounds, and in relation to the psychological impact of facilitating and providing emotional support to others. We found that facilitators were often at risk of burnout themselves due to lack of consideration given to the impact of running Rounds on them. The sustainability of Rounds therefore depends upon the provision of adequate support to mitigate these stressors. This should include:

-

(i)

Training sufficient numbers of facilitators (planning for sick leave, annual leave, succession planning);

-

(ii)

Ensuring the provision of administrative support for Rounds so that this is not an additional task taken on by facilitators (Rounds publicity, organising steering group meetings, booking rooms, organising food, coordinating sign-in and evaluation in Rounds, synthesising feedback to produce reports for internal and external use);

-

(iii)

Providing continued professional development (CPD) and supervision for facilitators and clinical leads to ensure they have a reflective space/psychological support that provides a sounding board (pre Rounds) and space for debriefing (post Rounds).

-

(iv)

Ensuring appropriate use of steering group members and active membership: appointing steering group members to cover a range of departments in the organisation; with clear roles that include attending Rounds and playing an active role in helping to sustain them (e.g. by helping to identify stories and panellists for Rounds). Rotating membership (e.g. every 6–12 months) can help with the sustainability of this and with spread to new parts of the organisation.

-

(i)

-

(d)

Raising awareness and understanding of Rounds: It can be difficult to explain what a Round is to someone that has never attended one before, as they are unlike any other intervention that staff would be familiar with. In our evaluation, we interviewed staff that told us they had been to a Round but it was clear they were talking about something else; and other staff who had heard of Rounds but didn’t think they were ‘invited’. Overcoming these misconceptions is important to enhancing reach and accessibility: we recommend using multiple communication modes (not just relying on electronic forms) to let people know about Rounds, perhaps incorporating available resources such as films depicting real or re-enacted Rounds (via https://www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk/our-work/schwartz-rounds/); and using more explanatory titles and information within publicity for Rounds (in particular emphasising that they are open to ALL staff and using titles that would spark interest and resonate across the organisation).

-

(e)

Encouraging attendance: Rounds will not be felt as required—or useful to—all staff, but we found that there were groups of staff that were less able to attend Rounds due to practical barriers. This particularly applied to ward based nursing and support staff who were not able to leave their patients/wards for long enough to attend Rounds, which were often held at lunch times (one of the busiest times for those working on wards). Some organisations are trialling ‘pop-up’ Rounds where Rounds are taken to ward based staff—these Rounds tend to be shorter (30 min) and often uni-disciplinary (e.g. nursing staff) and these have yet to be evaluated. Further attention should be paid to potential solutions to this, either in relation to workable solutions to enable staff to attend (e.g. on a rotational basis with other staff covering their roles to enable this); or by providing alternative forms of Rounds (see section below about creative alternatives to Rounds). Other staff may be encouraged to attend if they receive accreditation for attending (e.g. CPD points, which some organisations were offering), and others built Schwartz Rounds into their in-house training programmes, though it is important for Rounds fidelity that attendance is voluntary, not mandatory.

-

(f)

The importance of panel preparation: We uniquely identified this as a specific stage of Rounds (Stage 2), and found that it was a key aspect determining the success of a Round particularly in relation to psychological safety. Panel preparation enables panellists to shape their stories and to ensure that it is ‘safe’ to share; to hear about how the Round will run (and that their story may not be commented on by the audience, and not to take this personally); and to hear the other panellists stories. As well as ensuring safety and relevance, panel preparation also enables the facilitator to identify the themes that may come up in the Round itself. A key challenge is the time taken for this, in particular to meet with all panellists together in a group which was not always possible, but we recommend that at least one-to-one preparation occurs (even if by telephone).

-

(g)

Implementing creative adaptations of Rounds ‘peripheral components’: We identified that there were core (essential) components of Rounds that should not be adapted (Leamy, Reynolds, Robert, Taylor, & Maben, 2019), but that other aspects could potentially be modified to support adaptation to local contexts to support sustainability. Core components include: having senior clinical leadership; two facilitators (with appropriate skills as above) to maintain trust, safety and containment; that they are a group intervention; ongoing (not one-off) and not combined with other things; that food is provided; staff-only (not patients); that they use pre-prepared staff stories about the emotional impact of work to trigger audience reflection; and do not focus on the clinical detail or problem solving. Potentially adaptable components include the diversity of the audience (e.g. targeting specific staff rather than open to all); the source of stories (e.g. using filmed rather than live stories); having fewer panellists; and shortening the format (e.g. ‘pop-up’ Rounds (PoCF, 2016)) to reach those that cannot attend normally. These adaptations remain untested and may potentially dilute or change the outcomes.

-

(h)

Evaluating Rounds: Resisting the desire to demonstrate ‘hard’ outcomes from Rounds evaluation in single organisations: We found an expectation in some organisations that it was both possible and desirable to measure ‘outcomes’ to demonstrate the effectiveness of Rounds—either outcomes for staff and or for patients and carers. This is unsurprising given the prevailing healthcare culture of monitoring and targets and evidence-based medicine. However, together with being in contrast to the ‘counter-cultural space’ that we argue Rounds sits within, we also argue that an individual organisation would rarely be able to undertake a robust quantitative evaluation with sufficient ‘control group’ data for staff outcomes (our quantitative evaluation required ten organisations, many of whom had to be ‘new organisations’ to provide us with sufficient participants). In addition, whilst we based our selection of survey measures on our initial programme theory about how Rounds work to produce outcomes (including for example the role of reflection and compassion), we now have a more comprehensive understanding of how and why Rounds work to produce outcomes and would argue that such measures do not capture the full effects of Rounds. Furthermore, as Rounds are open to all staff which can attend as many or as few as they like—linking individual staff attendees to specific patient experiences or outcomes is fraught with methodological difficulty. We did not feel we could deliver a robust evaluation at the patient level due to not being able to control for all the many confounders that may also affect patients and carer experiences and outcomes. Other evaluators have also not been able to achieve this despite trying. Rather we sought to evaluate Rounds impact on staff well-being, and reported impacts on self, colleagues, patients and the organisation, drawing on evidence that has identified the link between staff wellbeing at work and patient experiences of care (Maben et al., 2012). We therefore recommend that organisations instead should focus on reported experiences of Rounds attendance, and capturing any ripple effects (changes in practice, perhaps through an annual survey of attenders to capture these). Our data suggest that it is important to ensure clarity at Board level regarding the complexity of evaluation, and to confirm their expectations (if any) for reporting and “evidence”, perhaps considering Schwartz Rounds steering groups reporting directly to the Board or a sub-committee.

6 Conclusions

Rounds are a complex intervention methodologically (e.g. comprising many interacting components, and non-linear causal pathways). They were developed in the USA and are now being taken up in other countries. Our national UK evaluation has identified how Rounds work to produce their outcomes creating ripple effects within and across organisations that facilitate cultural changes and changes in practice. In our study Rounds reduced poor psychological wellbeing for staff who regularly attended Rounds, and our in-depth qualitative case study data shed more light on how this happened and the mechanisms by which Rounds act as a counter-cultural space to have effects on individuals, teams, patients and the organisation. Key messages for researchers and for healthcare delivery are summarized below (Tables 17.2 and 17.3).

Notes

- 1.

The Point of Care Foundation was established in 2013 as an independent charity. Previously known as the Point of care programme established in 2007 and hosted at the King’s Fund.

References

Boorman, S. (2009). The final report of the independent NHS Health and well-being review. London: TSO: Department of Health.

Chambers, R., & Maxwell, R. (1996). Helping sick doctors. BMJ, 312(7033), 722–723.

DeFrank, R. S., & Cooper, C. L. (1987). Worksite stress management interventions: Their effectiveness and conceptualisation. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 2, 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb043385

deJonge, J., & Dollard, M. F. (2002). Stress in the workplace: Australian Master OHS and environment guide. Sydney, Australia: CCH.

Goetzel, R. Z., & Pronk, N. P. (2010). Worksite health promotion: How much do we really know about what works? What works in worksite health promotion systematic review findings and recommendations from the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38, S223–S225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.032

Goodrich, J. (2012). Supporting hospital staff to provide compassionate care: Do Schwartz Center Rounds work in English hospitals? JRSM, 105, 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110183

Graveling, R. A., Crawford, J. O., Cowie, H., Amati, C., & Vohra, S. (2008). A review of workplace interventions that promote mental wellbeing in the workplace. Edinburgh: Institute of Occupational Medicine.

Leamy, M., Reynolds, E., Robert, G., Taylor, C., & Maben, J. (2019). The origins and implementation of an intervention to support healthcare staff to deliver compassionate care: exploring fidelity and adaptation in the transfer of Schwartz Center Rounds® from the United States to the United Kingdom. BMC Health Services Research, 19, 457.

Lown, B. A., & Manning, C. F. (2010). The Schwartz Center rounds: Evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Academic Medicine, 85, 1073–1081.

Maben J., Peccei R., Adams M., Robert G., Richardson A., Murrells T., & Morrow, E. (2012). Exploring the relationship between patients’ experiences of care and the influence of staff motivation, affect and wellbeing. Final Report: NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation Programme.

Maben J., Taylor, C., Dawson, J., Leamy, M., McCarthy, I., Reynolds, E., et al. (2018). A realist informed mixed methods evaluation of Schwartz Center Rounds® in England. Health Services and Delivery Research, 6(37). Published in November 2018, https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr06370, https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hsdr/hsdr06370#/abstract

Maben, J., Leamy, M., Taylor, C., Reynolds, E., Shuldham, C., Dawson, J., et al. (2018). Understanding, implementing and sustaining Schwartz Rounds: An organisational guide to implementation. London: King’s College. https://www.surrey.ac.uk/content/schwartz-organisational-guide-questionnaire

Manzano, A. (2016). The craft of interviewing in realist evaluation. Evaluation, 22, 342–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389016638615

Marine, A., Ruotsalainen, J. H., Serra, C., & Verbeek, J. H. (2006). Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4), CD002892. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002892.pub2

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2009). Promoting mental wellbeing through productive and healthy working conditions: guidance for employers. London: NICE.

Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. London: Sage.

Point of Care Foundation. (2016). https://www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk/event/training-pop-rounds/. Accessed 15/08/19.

Reed, E., Cullen, A., Gannon, C., Knight, A., & Todd, J. (2015). Use of Schwartz Center Rounds in a UK hospice: Findings from a longitudinal evaluation. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 29, 365–366.

Robert, G., Philippou, J., Leamy, M., Reynolds, E., Ross, S., Bennett, L., et al. (2017). Exploring the adoption of Schwartz Center Rounds as an organisational innovation to improve staff wellbeing in England, 2009-2015. BMJ Open, 7(1), 1–10.

Schwartz, K. (1995, July 16). A patient’s story. Boston Globe Magazine.

Seymour, L., & Grove, B. (2005). Workplace interventions for people with common mental health problems. London: British Occupational Health Research Foundation.

Taylor, C., Xyrichis, A., Leamy, M., Reynolds, E., Maben, J. (2018). Can Schwartz Center Rounds support healthcare staff with emotional challenges at work, and how do they compare with other interventions aimed at providing similar support? A systematic review and scoping review. BMJ Open, 8, e024254. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024254n. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/8/10/e024254.full

Tetrick, L. E., & Quick, J. C. (2011). Overview of occupational health psychology: public health in occupational settings. In J. C. Quick & L. E. Tetrick (Eds.), Handbook of occupational health psychology (2nd edn., pp. 3–20). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Wren, B. (2016). True tales of organisational life. London: Karnac.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Maben, J., Taylor, C. (2020). Schwartz Center Rounds: An Intervention to Enhance Staff Well-Being and Promote Organisational Change. In: Montgomery, A., van der Doef, M., Panagopoulou, E., Leiter, M.P. (eds) Connecting Healthcare Worker Well-Being, Patient Safety and Organisational Change. Aligning Perspectives on Health, Safety and Well-Being. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60998-6_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60998-6_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-60997-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-60998-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)