Abstract

Over the past two decades, the survival of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) has increased constantly [1, 2]. No single advancement is responsible for this improvement, but a variety of essential elements like screening, better selection of patients including assessment by multidisciplinary teams (MDT), improved understanding of biology, better surgical techniques, improved postoperative care, and regular follow-up has together with an increased use of effective systemic therapy in the adjuvant and the palliative setting added to the overall survival benefit.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Over the past two decades, the survival of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) has increased constantly [1, 2]. No single advancement is responsible for this improvement, but a variety of essential elements like screening, better selection of patients including assessment by multidisciplinary teams (MDT), improved understanding of biology, better surgical techniques, improved postoperative care, and regular follow-up has together with an increased use of effective systemic therapy in the adjuvant and the palliative setting added to the overall survival benefit.

Since the introduction of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in 1957, numerous well-conducted randomized studies have proven its efficacy [3, 4]. For almost 40 years, 5-FU was practically the only available drug, and therefore numerous different treatment schedules were developed and compared. In the 1990s, it was established that biomodulation with folinic acid (FA) increased efficacy of 5-FU. However, the optimal combination of 5-FU and FA continued to be a matter of great debate—in which dose of 5-FU and FA, bolus or infusion, one or several days of therapy, and the sequence of 5-FU and FA were some of the many questions that were asked and discussed. Presently the most widely 5-FU/FA schedule is a combination of 5-FU bolus and 46 h infusion with FA (often referred to as the “de Gramont” regimen or LV5FU2). Adjuvant 5-FU/FA increases the chance of cure by absolutely 10% in colon cancer stage III and prolongs the median overall survival (OS) from 6 to 12 months in the palliative situation.

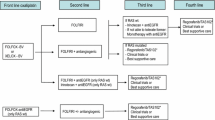

The era of modern combination therapy started in the late 1990s when it was shown that irinotecan prolonged survival in patients with 5-FU/FA refractory disease. Since then a large number of well-conducted randomized trials have proven the benefit of many new drugs in patients with CRC: irinotecan, oxaliplatin, two oral formulations of 5-FU (capecitabine and tegafur), and several targeted drugs—bevacizumab, cetuximab, panitumumab, ramucirumab, and aflibercept [3, 4]. In recent years, two new drugs (trifluridine/tipiracil and regorafenib) have been introduced in patients with chemo-refractory CRC [3, 5].

Even nowadays, a combination of 5-FU and FA continues to be the backbone of systemic therapy in patients with metastatic CRC—as first-line and second-line therapy. Optimal combination chemotherapy with 5-FU/FA and irinotecan or oxaliplatin generates tumour regression in 50% of patients with metastatic CRC. Progression-free survival (PFS) is prolonged to around 9 months, and with the use of several sequential lines of chemotherapy, median OS is now approaching 24 months, but only in fit selected patients who are fit enough to be included in clinical trials [6]. The addition of novel targeted agents further adds to efficacy of systemic therapy [3, 4]. However, when it comes to adjuvant therapy, only the combination of fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin has been shown to be superior to single agent 5-FU/FA.

As mentioned, the cornerstone of medical oncological therapy in patients with metastatic CRC is chemotherapy with targeted drugs. However, treatment of patients with metastatic CRC is changing from “one strategy fits all” to a more personalized approach based on clinical characteristics and molecular profiling [4, 7]. In the daily clinical practice, molecular profiling is used to identify therapeutically treatable alteration and to predict efficacy of targeted therapies. Currently, the molecular changes with immediate implication on the choice of therapy are rather limited, but RAS and BRAF status are used to select optimal treatment strategy in patients with metastatic CRC. Immunotherapy is effective but so far only in patients with deficient mismatch repair (MMR) or with microsatellite instability.

Around 30–40% of patients with CRC will develop hepatic metastases at some point during the course of the disease [8]. Surgical resection is the gold standard for patients with resectable colorectal liver metastasis (CRLM). After microscopic radical resection (R0), the expected 5-year survival is around 35% and even higher in recent selected series. Pre-and postoperative systemic therapy is used to reduce the risk of recurrence in patients with resectable CRLM, but major tumour regression has also permitted salvage surgery in 10–30% of patients with initially unresectable CRLM. Presently, around 10% of patients with CRLM are candidates for local treatment. This number will definitely increase due to introduction of newer surgical and ablative techniques and enhanced efficacy of systemic therapies. The optimal combination and sequence of these different modalities must be decided on by the MDT. Several chemotherapy regimens are known to induce hepatic injury as hepatic steatosis and sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. In such cases, surgical morbidity is increased but mortality is not higher if duration of preoperative chemotherapy is limited. However, it is important that patients are operated as soon as CRLM become resectable.

In the subsequent chapters of this new book, a number of outstanding experts will guide you through all aspects of oncologic therapy and decision-making in our patients. In many cases the optimal strategy has been established through several well-designed randomised studies, e.g. adjuvant postoperative therapy in a healthy patient after R0 resection for colon cancer stage III. However, there are still a large number of cases in which the decision-making is not as straightforward, because we are desperately lacking high-quality scientific evidence, and especially for these patients a MDT decision is mandatory.

Presently, one of the major challenges for a MDT are patients with rectal cancer. Optimal outcome is depending not only on high-quality surgery and pathology but also on excellent radiation techniques, best possible supplementary chemotherapy and long-term follow-up. A continuous quality control programme with feedback to the participants of the MDT is beneficial for the outcome.

How shall we treat a patient with resectable primary and resectable metastasis? Resection and systemic therapy must be combined but what is the optimal sequence—resection first or systemic therapy first? Should the primary always be resected in patients with synchronous non-resectable metastasis? Presently, we are awaiting results of ongoing randomized trials to answer these questions.

Most participants in MDT conference find them of huge importance because it makes the patient management more efficient, improves communication between different specialities, helps to prevent unnecessary investigations, and is a perfect model for education and training. Even though data from randomized studies are lacking, retrospective studies have revealed that a MDT-based strategy probably has contributed to a reduced local recurrence rate but also to an improvement in survival [9, 10]. Fortunately, MDT has nowadays been established at most colorectal centres.

We hope that the next chapters will inspire you in your daily practice and that it will add to an optimal management of your patients.

References

Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3677–83.

Sorbye H, Cvancarova M, Qvortrup C, et al. Age-dependent improvement in median and long-term survival in unselected population-based Nordic registries of patients with synchronous metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2354–60.

Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1386–422.

Pfeiffer P, Köhne CH, Qvortrup C. The changing face of treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2019;19:61–70.

Andersen SE, Andersen IB, Jensen BV, Pfeiffer P, Ota T, Larsen JS. A systematic review of observational studies of trifluridine/tipiracil (TAS-102) for metastatic colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2019;58:1149–57.

Sorbye H, Pfeiffer P, Cavalli-Bjorkman N, et al. Clinical trial enrolment, patient characteristics, and survival differences in prospective registered metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cancer. 2009;15:4679–87.

Pfeiffer P, Qvortrup C. How to select colorectal cancer patients for personalized therapy. EBioMedicine. 2019;41:36–7. pii: S2352-3964(19)30094-5.

Pfeiffer P, Gruenberger T, Glynne-Jones R. Synchronous liver metastases in patients with rectal cancer: can we establish which treatment first? Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918787993. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758835918787993.

Wille-Jorgensen P, Bülow S. The multidisciplinary team conference in rectal cancer—a step forward (Editorial). Color Dis. 2009;11:231–2.

MacDermid E, Hooton G, MacDonald M, et al. Improving patient survival with the colorectal cancer multi-disciplinary team. Color Dis. 2009;11:291–5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pfeiffer, P., Qvortrup, C. (2021). Introduction to Oncology. In: Baatrup, G. (eds) Multidisciplinary Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58846-5_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58846-5_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-58845-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-58846-5

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)