Abstract

Szunomár explores the main characteristics of Chinese investments and types of involvement and identifies the home and host country determinants of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) within the East Central European (ECE) region, with a focus on structural, institutional and political factors. The chapter presents the historical evolution and main characteristics of outward FDI as well as the major push drivers and public policies. By looking at the changing patterns of Chinese outward FDI in the ECE region and Chinese investors’ potential motivations when choosing a specific destination for their investments, Szunomár assumes that pull determinants of Chinese investments in the ECE region differ from those of Western companies in terms of specific institutional and political factors that seem especially important for Chinese companies.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- China

- East Central Europe (ECE)

- Outward foreign direct investment (outward FDI)

- Push and pull factors of outward FDI

- Structural factors

- Institutional factors

- Political factors

1 Introduction

Chinese outward foreign direct investment (FDI) has increased in the past decades; however, in the last one and a half decades this process has accelerated significantly. In 2012, China became the world’s third largest investor—up from sixth in 2011—behind the US and Japan and it still holds its position with 129.8 billion USD in 2018. In the meantime, the stock of Chinese outward FDI has reached 1938 billion USD according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) data. As a result, Chinese multinational enterprises (MNEs) are not only the largest overseas investors among developing countries but are a top global investor with continuing growth potential. Several factors fuelled this shift, including the Chinese government’s wish for globally competitive Chinese firms or the possibility that outward FDI can contribute to the country’s development via multiple channels, such as through (1) investments in natural resources exploration, (2) export of domestic technologies, products, equipment and labour, (3) technological upgrading and (4) increasing competitiveness by promoting brands and by building global networks of sales, supply and production (Sauvant and Chen 2014: 141–142; Luo et al. 2010: 76; Caseiro and Masiero 2014: 248).

Although traditionally Chinese outward FDI is directed towards the countries of the developing world, Chinese investments into the developed world, including Europe, increased significantly in the past decade. While the resource-rich regions remained important for Chinese companies, they started to become increasingly interested in acquiring European firms after the global economic and financial crisis of 2008. The main reason behind the shift towards such an entry mode is that through European firms Chinese companies can have access to important technologies, successful brands and new distribution channels (Clegg and Voss 2012: 16–19). As a result, Europe has emerged as one of the top destinations for Chinese investments. According to Rhodium Group’s statistics, annual FDI flows in the 28 EU economies has grown from 700 million EUR in 2008 to 30 billion EUR in 2017, which represents a quarter of the total Chinese FDI outflows that year.

Nevertheless, Chinese approach towards Europe is far from being unified since China follows different motives and uses different approaches when dealing with different countries or regions of Europe (Szunomár 2017): the access to successful brands, high technology and know-how motivates China when entering Western European markets, investments in the green energy industry and sustainability brings Chinese companies to Nordic countries, and greenfield investments (manufacturing), acquisitions and recently also infrastructural projects pulls them to Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), including also the non-EU member Western Balkan countries.

In recent years Chinese companies have increasingly targeted CEE countries, with East Central Europe (ECE)—the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia—among the most popular destinations. Compared with the Chinese economic presence in the developed world or even in Europe, China’s economic impact on the ECE countries is still relatively small but it has accelerated significantly in the past decade. This development is quite a new phenomenon but not an unexpected one. On the one hand, the transformation of the global economy and the restructuring of China’s economy are responsible for growing Chinese interest in the developed world, including Europe. On the other hand, ECE countries have also become more open to Chinese business opportunities, especially after the global economic and financial crisis of 2008, with the intention of decreasing their economic dependency on Western (European) markets.

In line with the above, the aim of this chapter is to map out the main characteristics of Chinese investment flows, types of involvement, and to identify the home and host country determinants of Chinese FDI within the ECE region, with a focus on structural/macroeconomic, institutional and political pull factors. According to our hypothesis, pull determinants of Chinese investments in the ECE region differ from those of Western companies in terms of specific institutional and political factors that seem important for Chinese companies. This hypothesis echoes the call to combine macroeconomic and institutional factors for a better understanding of internationalization of companies (Dunning and Lundan 2008). The novelty of this chapter is that—besides macroeconomic and institutional factors—it incorporates political factors that may also have an important role to play in attracting emerging, especially Chinese, companies to a certain region.

In order to assess the role and importance of outward FDI from China towards the ECE region, it must be evaluated within a global context, taking into account its geographical, as well as sectoral, distribution and major push as well as pull factors. Therefore, this chapter first describes the driving forces behind the international expansion strategies of Chinese MNEs by presenting the historical evolution and main characteristics of outward FDI as well as the major push drivers and public policies. Next, it examines the changing patterns of Chinese outward FDI in the ECE region by showing the major trends, patterns and available data. It then discusses the main trends, patterns and Chinese investors’ potential motivations when choosing a specific ECE destination for their placements, which is followed by the author’s conclusions.

As the topic of Chinese FDI in European peripheries is new and has started to draw academic attention only recently and the available literature is rather limited and based mostly on secondary sources, the author conducted personal as well as online interviews with representatives of various Chinese companies in the ECE region. Personal interviews were conducted at four companies; where personal interviews were not applicable (three companies), the author used other sources, such as former employees of different Chinese companies that have invested in ECE, business professionals, experts and academics from ECE countries. The interviews were conducted anonymously by the author between May 2017 and September 2019 and all interviewees were guaranteed confidentiality. Each interview lasted from one to two hours. The author used semi-structured questionnaires; that is she drew up a questionnaire and structured the interview based on some basic questions concerning the background of investment, motivations before the investment and the significance of the same factors later, a few years after the investment took place. Several more questions arose based on the original questions and the responses to them; therefore, the structure of each interview was unique. The answers were noted down by the author in detail and were then analysed. Later, information from the company interviews was supplemented by data from the balance sheets of the subsidiaries.

The author will usually take into account FDI by mainland Chinese firms (where the ultimate parent company is Chinese), unless marked explicitly that due to data shortage or for other purposes they deviate from this definition. Since international statistics or national data in FDI recipient ECE countries and Chinese data show significant differences, these datasets will be compared to point out the potential source of discrepancies in order to get a more complex and nuanced view of the stock and flow of investments. Statistics from the Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China (MOFCOM), UNCTAD and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) will be considered and sometimes compared.

2 Driving Forces Behind the International Expansion Strategies of Chinese MNEs

From the late 1970s, in hand with the so-called “Open Door” policy reforms, the Chinese government encouraged investments abroad to integrate the country with the global economy, although the only entities allowed to invest abroad were state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The total investment of these first years was not significant and concentrated on the neighbouring countries, mainly Hong Kong. The regulations were liberalized after 1985 and a wider range of enterprises—including private firms—were permitted to invest abroad. After Deng Xiaoping’s famous journey to South China in 1992, overseas investment increased dramatically; Chinese companies established overseas divisions almost all over the world, concentrated mainly in natural resources. Nevertheless, according to UNCTAD statistics, Chinese outward FDI averaged only 453 million USD per year between 1982 and 1989 and 2.3 billion USD between 1990 and 1999.

In 2000, before joining the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Chinese government initiated the so-called going global or “zou chu qu” policy, which was aimed at encouraging domestic state-owned as well as private companies to become globally competitive. It introduced new policies to induce firms to engage in overseas activities in specific industries, notably in trade-related activities. In 2001 this encouragement was integrated and formalized within the tenth five-year plan, which also echoed the importance of the “Go Global” policy (Buckley et al. 2007). This policy shift was part of the continuing reform and liberalization of the Chinese economy and also reflected the Chinese government’s desire to create internationally competitive and well-known companies and brands. Both the 11th and 12th five-year plans stressed again the importance of promoting and expanding outward FDI, which became one of the main elements of China’s new development strategy.

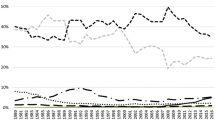

Chinese outward FDI has steadily increased in the last decade (see Figs. 3.1 and 3.2), particularly after 2008, due to the above-mentioned policy shift and the global economic and financial crisis. The crisis brought more overseas opportunities to Chinese companies to raise their share in the world economy as the number of ailing or financially distressed firms has increased. While outward FDI from the developed world decreased in several countries because of the recent global financial crisis, there was a greater increase in Chinese outward investments: between 2007 and 2011, outward FDI from developed countries dropped by 32 per cent, while China’s grew by 189 per cent (He and Wang 2014: 4; UNCTAD 2013). As a consequence, according to the World Investment Report 2013, in the rankings of top investors, it moved up from the sixth to the third largest investor in 2012, after the US and Japan—and the largest among developing countries—as outflows from China continued to grow, reaching a record level of 84 billion USD in 2012. Thanks largely to this rapid increase of its outward FDI in recent years China also became the most promising source of FDI when analysing FDI prospects by home region (UNCTAD 2013: 21).

2.1 Characteristics of Chinese FDI Globally

As has been already mentioned in the introduction, traditionally Chinese outward FDI is directed towards the developing world, especially Asia; however, Chinese investments into the developed world have increased significantly in the past decade. The EU, for instance, received 0.4 billion USD investment flow from China in 2003, 6.3 billion USD in 2009—with an annual growth rate of 57 per cent, which was far above the growth rate of Chinese outward FDI globally—and 35 billion in 2016 (Clegg and Voss 2012; Hanemann and Huotari 2017: 4). While the resource-rich regions remained important for Chinese companies, they started to become more and more interested in acquiring European firms after the financial and economic crisis. The main reason for this is that through these firms Chinese companies can have access to important technologies, successful brands and new distribution channels, while the value of these firms has fallen too due to the global financial crisis (Clegg and Voss 2012: 16–19).

This increase is impressive by all means; however, according to Chinese statistics, China still accounts for less than ten per cent of the total FDI inflows into the EU and the US. Nevertheless, during the examination of the actual final destination of Chinese outward FDI, Wang (2013) found that as a result of round-tripping investments—when the investment is placed in offshore financial centres only to flow it back in the form of inward FDI to China to benefit from fiscal incentives designed for foreign investors—developed countries receive more Chinese investments than developing economies: according to his project-level data analysis, 60 per cent of Chinese outward FDI went to developed economies like Australia, Hong Kong, the US, Germany and Canada.

As Fig. 3.2 shows outward FDI has started to gain momentum in the new millennium. The year of the global economic and financial crisis, 2008, provided a tremendous impetus to Chinese outward FDI, while 2015 was the first year when Chinese outward FDI exceeded inward FDI. However, following this rapid growth, China’s global outward FDI has started to decline from 2017 onwards, as a result of Beijing’s administrative control to limit capital outflows. This control has been maintained in 2018 (and 2019) too; consequently, outward FDI flows declined further. Besides the already mentioned administrative control, the Chinese state also “pressured highly leveraged firms to sell off overseas assets; and it reduced liquidity in the financial system amidst a broader clean-up of the financial sector, thus drying out financing channels for overseas investments” (Hanemann et al. 2019: 8). Another potential reason for these declining outflows could be that more and more countries have continuing reservations about Chinese companies’ investments, including national security concerns that result in, for example, the implementation of foreign investment screening mechanisms in many developed countries.

Several experts believe that Chinese outward FDI could be greater if host countries were more hospitable. According to He and Wang (2014: 4–5), there are several reasons for this: (1) SOEs are the dominant players in Chinese outward FDI and they are often viewed as a threat for market competition as they are supported by the Chinese government; (2) foreign companies often complain that Chinese companies may displace local companies from the market as they take technology, resources and jobs away and (3) there are fears about Chinese companies’ willingness to adapt to local environment, labour practices and competition. Although the above-mentioned problems indeed exist, they are often overestimated as Chinese companies are willing to accommodate to the international rules of investment as well as to the local environment (Sass et al. 2019).

According to Scissors (2014: 5), however, if the concern is about national security, the role of Chinese ownership status is overblown as Chinese rule of law is weak, which means that a privately owned company has to face as much pressure and constraint as its state-owned competitor. Nevertheless, it is worth differentiating between the two types of SOEs: locally administered SOEs (LSOEs) and centrally administered SOEs (CSOEs). Most of the LSOEs operate in the manufacturing sector and they are facing competition from both private companies and other LSOEs, while CSOEs are smaller in number but more powerful as they operate in monopolized industries such as finance, energy and telecommunication (He and Wang 2014: 5–6). Although the share of private firms is growing, SOEs still account for the majority—more than two-thirds—of total Chinese outbound investments. However, the range of investors is broader; next to state-owned and private actors it includes China’s sovereign wealth fund and firms with mixed ownership structure. The role of SOEs seems to be declining in the past few years, although the government will continue to emphasize their importance as it relies on the revenue, job creation and provision of welfare provided by the SOEs (He and Wang 2014: 11–12).

Regarding the entry mode of Chinese outward investments globally, greenfield FDI continues to be important, but there is a trend towards more mergers and acquisitions (M&As) and joint venture projects overseas. Overall, greenfield investments of Chinese companies outpace M&As in numerical terms; however, greenfield investments are smaller in value in total as these include the establishment of numerous trade representative offices.

As Clegg and Voss note (2012: 19), the industry-by-country distribution of Chinese outward FDI is difficult to determine from Chinese statistics. However, based on their findings, it can be stated that Chinese investments in the mining industry are taking place mainly in institutionally weak and unstable countries with large amounts of natural resources and that these investments are normally carried out by SOEs. Investments in manufacturing usually take place in large markets with low factor costs, while Chinese companies seek technologies, brands, distribution channels and other strategic assets in institutionally developed and stable economies.

Generally speaking, Chinese outward FDI is characterized by natural resource-seeking, market-seeking (see Buckley et al. 2007) and recently also strategic asset-seeking motives (see Di Minin et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2012); however, motivations differ between regions. In developed economies Chinese investment is less dominated by natural resource-seeking or trade-related motives but more concerned with the wide range of objectives, including market-, efficiency- and strategic assets-seeking motives. In the case of developed countries, Chinese SOEs usually have the majority of deal value but non-state firms make the greater share of deals (Rosen and Hanemann 2009). In addition to greenfield investments and joint ventures, China’s M&A activity in developed countries has recently gained momentum and continues an upward trend since more and more Chinese firms are interested in buying overseas brands to strengthen their own.

2.2 Push Factors and Public Policies Behind Chinese Outward FDI

As mentioned in Chap. 1 of this book, driving forces of outward FDI can be grouped into push and pull factors (or home country and host country determinants, respectively) to differentiate between the factors that drive investment out of the home country and those that attract investments into another (host) country. When it comes to push factors, we can differentiate between institutional and structural types. While structural push factors are related to the home country’s domestic economy and market, institutional push factors are related to the distance between the home and host countries—such as cultural proximity, which can be measured by the size of the Chinese diaspora in the host country—and government policies.

China’s rise is often compared to the post-war “Asian Miracle” of its neighbours. When we analyse the internationalization processes of Japanese, Korean and Chinese companies there are indeed several common features and similarities. Nevertheless, one of the main common characteristics of these three nations is the creation and support of the so-called national champions, that is, domestically based companies that have become leading competitors in the global market. In fact, during their developmental period, both the Japanese and Korean governments provided strong state financial support to their companies to protect and promote them as well as to strengthen them against international competition. China has followed them later in subsidizing domestic industries and supporting their overseas activities, for example, in the form of government funding for outward FDI.

Irwin and Gallagher (2014) found that—unlike Japan or Korea—China’s market entry has more to do with developing project expertise and supporting exports than it does with tariff-hopping or outsourcing industries fading on the mainland. They identified two major reasons for China’s high (31%) ratio of outward FDI lending to total outward FDI. “First, China has a greater incentive to give outward FDI loans than Japan or Korea ever did because its borrowers are state-owned so it can more easily dictate how they use the money. Second, China has a greater capacity to give outward FDI loans because it has significantly higher savings and foreign exchange reserves than Japan and Korea, both today and especially during equivalent developmental stages” (Irwin and Gallagher 2014: 22–23). Peng (2012) reports that Chinese MNEs are characterized by three relatively unique aspects: (1) the significant role played by home country governments as an institutional force, (2) the absence of significantly superior technological and managerial resources and (3) the rapid adoption of (often high-profile) acquisitions as a primary mode of entry.

According to the “Go Global” strategy, Chinese companies should evolve into globally competitive firms; however, Chinese companies go abroad for varieties of reasons. The most frequently emphasized motivation is the need for natural resources, mainly energy and raw materials, in order to secure China’s further development (resource-seeking motivation). Mutatis mutandis, they also invest to expand their market or diversify internationally (market-seeking motivation). Nevertheless, services such as shipping and insurance are also significant factors for outward FDI for Chinese companies if they export large volumes overseas (Davies 2013: 736). Moreover, despite China’s huge labour supply, some companies move their production to cheaper destinations (efficiency-seeking motivation), for example, Southeast Asia. Recently, China’s major companies are also looking for well-known global brands or distribution channels and management skills, while another important reason for investing abroad is technology acquisition (strategic asset-seeking motivation). Scissors (2014: 4) points out that clearer property rights—compared to the domestic conditions—are also very attractive to Chinese investors, while Morrison (2013) highlights an additional factor, that is, China’s accumulation of foreign exchange reserves: instead of the relatively safe but low-yielding assets such as US treasury securities, the Chinese government wants to diversify and seeks more profitable returns.

In China, initially, only large SOEs from the natural resource sector were supported to invest abroad to overcome the resource scarcity of the Chinese economy. Later on, to help small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) develop their international markets, a government regulation on capital support for SMEs was introduced in 2000, at the very beginning of the “going global” policy. In contrast, the promotion of outward FDI by privately owned companies was only approved in February 2006.

However, the government’s “paternalism” over outward investments has not ended with the liberalization steps listed above. Through the approval process for outward FDI projects and access to foreign exchange and preferential loans, the government can exert direct influence on the growth and patterns of outward investments. The MOFCOM requested that companies invest in countries that

-

1.

have a close relationship with China,

-

2.

exhibit complementarities to the Chinese economy,

-

3.

are important trading partners of China,

-

4.

have signed investment and taxation agreements with China and

-

5.

are part of an important economic region in the global economy (MOFCOM 2004).

The desired geographical and industry direction of Chinese companies’ investment has been governed by the so-called “Catalogue of Industries for Guiding Foreign Investment”. The Catalogue has usually been issued by the National Development and Reform Commission and the MOFCOM. Initially, in the early 2000s, there were 67 recommended countries and 7 recommended industries for Chinese outward FDI. The country recommendations included 26 Asian countries (three in Central Asia), 13 African countries, 12 European countries (10 of them in the EU, old member states + Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland), 11 countries in North and South America and 5 countries in Oceania.

The Catalogue retains the classification of industries based on those that are encouraged, restricted or prohibited. For manufacturing, the most recommended industries are usually electric machines and consumer electronics, while for services, trade and distribution were suggested most often. In the highly technologically developed EU member countries, France, Germany, the UK and Sweden, investment in R&D was advocated as well. Rather surprisingly, investment in IT services was recommended in the “new” EU member countries.

China is indeed paradigmatic for state control of major corporations. However, in opposition to older versions of state capitalism and developmental states, there is neither a classical top-down control nor a “single-guiding enterprise model” such as the South Korean Chaebol or Japanese Keiretsu system. We can distinguish between different views on the characteristics of Chinese state control. One possible opinion is Nölke et al.’s (2015) state-permeated market economy, where mechanisms of loyalty and trust between members of state-business coalitions are based on informal personal relations. Witt and Redding (2013) consider the Chinese system as a system combining predatory elements with personal relations, while the Chinese themselves are emphasizing the advantages of the strong but effective government that provides internal as well as external stability.

We also support the idea that China forms a unique model on its own, which can be characterized by a sustained—or even never-ending—transition from socialism to capitalism. In China, there are new forms of profit-oriented and competition-driven state-controlled enterprises, such as China Mobile, that have emerged recently, while there are several private firms and public-private hybrids, such as Huawei, Lenovo or Geely, that have also been able to become successful companies on the Chinese market as well as globally (Nölke et al. 2015). These days, such non-state—but politically supported—national firms are considered—and treated—as “national champions” by state managers: they are or were protected from competition and granted different types of state support, including, for example, export subsidies (Naughton 2007; Ten Brink 2013). With some exceptions—such as the IT sector, which is deeply integrated into global production networks—most industries are dominated by national (state-controlled, hybrid and private) capital and not by foreign multinationals (Nölke et al. 2015).

3 Chinese Outward FDI in ECE

Although various Chinese companies have been operating in Europe since the early 2000s, they are still facing challenges. Due to the geographical, cultural and institutional distance between the home and host countries, Chinese companies—like all other MNEs—suffer from the “liability of foreignness” (Kostova and Zaheer 1999; Hymer 1976), while they also suffer from—as Amendolagine and Rabellotti (2017) call it—the “liability of emergingness”, which is related to their emerging market origin, reducing their legitimacy in advanced markets (Madhok and Keyhani 2012; Ramachandran and Pant 2010). The case of Chinese information and communications technology (ICT) companies such as Huawei is even more complex: in addition to these above-mentioned challenges, they also have to face national security concerns raised by most of the European states (Muralidhaara and Faheem 2019).

Chinese FDI flows to Europe, more specifically to the EU, peaked in 2016 when Chinese companies invested 37 billion EUR in the EU. It was a 77 per cent increase from the previous year (Hanemann and Huotari 2017: 4). From 2017 onwards, as Chinese global outward FDI has dropped, Chinese FDI transactions in the EU have also declined: in 2018 Chinese companies invested 17.3 billion EUR based on MERICS’s report (Hanemann et al. 2019). However, this report also outlines the fact (p. 9) that Chinese outward FDI flows in 2018 would have been significantly higher if transactions connected to the acquisitions of stakes below 10 per cent would have been added to them.Footnote 1 The report mentions (on p. 9) the 7.3 billion EUR acquisition of a 9.7 per cent stake in Daimler in February 2018 as an example for recent acquisitions of stakes right below that threshold.

Figure 3.3 presents those EU countries (+ the UK) that host more than one billion USD Chinese FDI stock.Footnote 2 Majority of the top destinations are Western, Northern and Southern European countries with only one ECE country—Hungary—on the list of the top 12. Germany, France and Sweden—the top three destinations—together host more Chinese investment than the remaining nine countries combined. Chinese FDI stock in the ten new CEE member states—in those CEE countries that joined the EU in 2004 and 2007Footnote 3—is relatively modest when compared to that in the core EU countries. The ten new member states together host a bit less than 5000 million USD Chinese FDI stock, which represents a bit more than six per cent of the total Chinese investment stock in the EU. Annual FDI flows are characterized by rather hectic movements and often related to one or two transactions per year. In 2018, Luxembourg, Sweden and Italy were the major receivers of Chinese MNEs’ transactions; in 2017, it was Sweden, the UK and Portugal.

In the past years Chinese companies gained foothold in a wide range of industries in Europe. According to MERICS-Rhodium Group calculations (Hanemann et al. 2019), in 2018 the top sectors included automotive, financial and business services, ICT and health and biotech; in 2017 the most popular sectors were transport, utilities and infrastructure, ICT and real estate. The share of SOEs in total Chinese investment in Europe had started to decline between 2010 and 2012 (to 80–90 per cent); reached the lowest peak in 2016 (36 per cent); increased again in 2017 as a result of some major transactions of SOEs as well as the already mentioned capital controls that affected manly the private companies; and decreased again (to 41 per cent) in 2018 (Hanemann et al. 2019: 13–14).

3.1 Characteristics and Major Trends of Chinese Outward FDI in ECE

The transition of CEE—including ECE—countries from centrally planned to market economies resulted in increasing inflows of FDI to these countries. During the transition, the region went through radical economic changes which had been largely induced by foreign capital. Foreign MNEs realized significant investment projects in this region and established their own production networks. Although the majority of investors arrived from Western Europe, the first phase of inward Asian FDI also occurred right after the transition: Japanese and Korean companies indicated their willingness to invest in the ECE region even before the fall of the iron curtain. Their investments took place during the first years of the democratic transition. The second phase came in the new millennium, when the Chinese government initiated the “Go Global” policy, which was aimed at encouraging domestic companies to become globally competitive. Therefore Europe—including European peripheries—also became a target region for Chinese FDI (see Szunomár 2017).

Although China considers the CEE region as a bloc (this is one of the reasons for creating the 16 +1 initiative, which is a joint platform for the 16 CEE countries—now 17, including Greece—and China), some countries seem to be more popular investment destinations than others. CEE countries host Chinese FDI to varying degrees: the four Visegrád countries, Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, take more than 75 per cent of the total Chinese outward FDI to the broader CEE region, while the other CEE countries—despite slight increases in many cases—have not received significant amounts of Chinese FDI flows so far.Footnote 4 The reason behind this representation is twofold. On the one hand, Chinese companies prefer EU member states. As Chinese companies are often targeting EU markets with their products, they prefer to establish or purchase company sites in the EU member states to avoid trade barriers such as tariffs and non-tariff barriers (e.g. quotas or embargoes) in market access. On the other hand, China tries to play safe. It targets with FDI CEE countries that have already attracted investments from elsewhere, for example, the US, Japan or Western Europe, Germany, in particular.

The selected five ECE countries account for a major share of the population (around 66 million) and economic output (more than 1000 billion USD according to the World Bank) of CEE. Moreover, all of the five countries have strengthened their relations with China in recent years. Among ECE countries, Hungary, Czechia and Poland have received the bulk of Chinese investment in recent years, while Slovakia and Slovenia lag a little behind due to their small size and lack of efficient transport infrastructure. Besides stock and flow amounts, comparison of the data of the ECE countries shows that in per-capita terms, too, Hungary is the most important host country for Chinese FDI as it has more FDI per capita than the other four.

As can be seen from Fig. 3.4, Chinese outward investment stock in the five ECE countries has steadily increased in the last one and a half decades, particularly after 2004 and 2008: after the countries’ accession to the EU and the economic and financial crisis, respectively. According to Chinese statistics, there was a real rapid increase from 9.6 million USD in 2004 to 673 million USD in 2010. By 2017, the amount of Chinese investments had further increased and reached 1009 million USD according to the data published by the MOFCOM.

At this point, it is important to note that MOFCOM statistics are adequate to show the main trends of Chinese outward FDI stocks and flows; however, apart from this, they prove to be a less reliable data source as they do not show the Chinese investments that have flowed to a country through a foreign country, company or subsidiary. To identify the home country of the foreign investor who ultimately controls the investments in the host country, the new International Monetary Fund (IMF) guidelines recommend compiling inward investment positions according to the Ultimate Investing Country (UIC) principle. Therefore we decided to use the database of the OECD as it tracks back data to the ultimate parent companies (see Fig. 3.5). When comparing the two datasets—MOFCOM and OECD—we find huge discrepancies that justify the assumption that Chinese companies are indeed using intermediary companies when investing in Europe, including in ECE countries. It also confirms that Chinese FDI is much more significant in the ECE region—especially in Czechia, Hungary and Poland—than previously thought.

Based on OECD statistics, FDI flows are relatively hectic (see Fig. 3.6), which probably means that FDI flows from China are connected to one or two big business deals per year. Disinvestments are less characteristic for the majority of the analysed countries; however, one big disinvestment indeed took place in Czechia in 2018, which is probably the result of the financial problems of one particular Chinese company, CEFC China Energy, a major Chinese company that invested in Czechia.

As has been already mentioned, China’s economic impact on ECE countries—although accelerated significantly in the past decade—is small; Chinese investments are still dwarfed by, for example, German MNEs’ investments into these countries. When calculating percentage shares, we found that Chinese FDI stocks are around 1 per cent of the total inward FDI stocks in ECE countries (see Fig. 3.7). As a result, China’s share of the total FDI in ECE is still far from being decisive: it is below 1 per cent for Czechia, Slovakia and Poland and below 2.5 per cent for Hungary and Slovenia. It is worth mentioning that in ECE countries, (Western) European investors are still responsible for more than 70 per cent of the total FDI stocks, while among non-European investors, companies from the US, Japan and South Korea are typically more important players than those from China.

3.2 Changing Patterns of Chinese MNEs’ Activities in ECE

As presented in Table 3.1, Chinese investors typically target secondary and tertiary sectors of the selected five ECE countries. Initially, Chinese investment flowed mostly into manufacturing (assembly), but over time, services have attracted more and more investment as well. For example, in Hungary and Poland there are branches of the Bank of China and the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China as well as offices of some of the largest law firms in China, such as Yingke Law Firm (established in Hungary in 2010 and in Poland in 2012) and Dacheng Law Offices (established in Poland in 2011 and in Hungary in 2012). The main Chinese investors targeting these five countries are primarily interested in telecommunication, electronics, the chemical industry and transportation.

The main entry modes of and sectors targeted by Chinese investment are similar in all ECE countries, despite being more diverse in the more popular target countries (Hungary and Poland). With regard to certain sectors, such as tourism, Chinese companies have preferred to target Slovenia.

Although the main entry mode used to be greenfield in the first years after Chinese companies had discovered the ECE region, M&As became more frequent later on, especially after the global economic and financial crisis of 2008. However, ECE countries—unlike countries in, for example, Western Europe—are not offering too many M&A opportunities since the number of successful, globally competitive companies are lower in the region. The low number of such acquirable companies is one of the potential reasons for the lack of new investments in these countries in recent years. On the one hand, Chinese companies have been increasingly motivated by gaining access to brands and new technologies and by discovering market niches that they can fill on European markets in the past decade. On the other hand, new Chinese greenfield projects have been targeting less developed regions (of Europe) with low factor costs. The ECE region lies somewhere in between: it has just a few good M&A deals while it is a less attractive destination for greenfield projects when compared to countries, for example, in the Balkans. Nevertheless, the ECE region’s position as a manufacturing or logistic base is still important for the Chinese MNEs—due to EU membership of these countries and the resulting “Made in EU” label on products assembled here—as will be explained in more detail in Chap. 4.

The Amadeus database, which provides information for public and private companies across Europe, lists 413 companies with Chinese ultimate owner in the five ECE countries: 230 in Czechia, 14 in Hungary, 61 in Poland, 103 in Slovakia and 5 Slovenia. More than half (243) of those 413 companies are located in the respective capitals of the five ECE countries, but the majority of the other companies are also operating in bigger cities of the analysed countries or in smaller cities near the capitals.

It has to be emphasized though that the number of companies listed by the Amadeus database does not really reflect the amount of Chinese FDI stock in these countries since—as mentioned above—Hungary hosts the majority of Chinese FDI—almost two billion USD—in the region, followed by Poland and Czechia. There are three potential reasons for this phenomenon. First, this database—as many other similar databases—seems to be incomplete as it does not include all of the Chinese companies that have invested in the ECE countries. For example, in the Hungarian case, for some reason, even some of the most significant investors are not listed by the Amadeus database: Huawei, which has its logistic centre as well as parts of its assembly activity in Hungary; BYD, which produces electronic buses in Northern Hungary; and Joyson, which develops and manufactures automotive safety systems in the eastern part of the country, just to mention a few. Second, majority of the numerous companies that are listed by Amadeus in, for example, Czechia or Slovakia are small wholesale or retail companies or firms operating restaurants or mobile food service activities. They employ a few people, and their assets as well as turnover are not very significant. Third, Hungary also hosts a lot of Chinese wholesale and retail companies, as well as restaurants, but those are operated by local Chinese nationals, that is, by Chinese people that arrived in the country in the late 1980s or the early 1990s when there were no visa requirements between the two countries. As a result, these companies do not appear in the Amadeus database. According to the company information database of Opten Ltd Hungary,Footnote 5 there were 1117 companies registered in Hungary with Chinese ownership in 2019.

4 Host Country Determinants of Chinese Outward FDI in the ECE Region

Chinese MNEs’ motivations are often different from those of developed countries. For example, as Hanemann (2013) points out, there are commercial reasons behind most investments: (1) the acquisition of well-known brands or (high-)technology to increase competitiveness and (2) money-saving by moving towards higher value-added activities in countries where regulatory frameworks are more developed.

As mentioned already, host country determinants—or pull factors—are those characteristics of the host country markets that can help attract MNEs’ investment. Pull factors—just like push factors—can be grouped into institutional and structural factors. We can further categorize institutional factors by dividing them into two levels: the supranational level and the national level. Both levels are important elements in the location decisions of Chinese companies investing in the five ECE countries (see McCaleb and Szunomár 2017). Based on the literature mentioned in the Chap. 1 as well as based on interviews conducted with company representatives and experts, in the case of Chinese MNEs, the main structural and institutional pull factors are presented in Table 3.2.

4.1 ECE Countries’ Structural and Institutional Pull Factors for Chinese MNEs

When searching for possible pull factors that could make ECE countries a favourable investment destination for Chinese investors, the labour market is to be considered as one of the most important elements: a skilled labour force is available in sectors for which Chinese interest is growing, with labour costs being lower than the EU average. However, there are differences within the broader CEE region as well; unit labour costs are usually cheaper in Bulgaria and Romania than in the five ECE countries. Corporate taxes can also play a role in the decision of Chinese companies to invest in the region. Nevertheless, the differences in labour costs and corporate taxes within the broader CEE region do not really seem to influence Chinese investors. After all, there is more investment from China in ECE countries (especially in Czechia, Hungary and Poland) than in Romania or Bulgaria, where labour costs and taxes are lower. This can be explained by the theory of agglomeration as outward FDI in ECE countries is the highest in the region (see McCaleb and Szunomár 2017).

Although the above-mentioned efficiency-seeking motives play a role, the main type of Chinese FDI in ECE countries is definitely market-seeking investment: by entering these markets, Chinese companies have access to the whole EU market; moreover, they might also be attracted by free trade agreements between the EU and third countries, such as Canada, and the EU neighbouring country policies as they claim that their ECE subsidiaries are to sell products in the ECE host countries, the EU and Northern American or even global markets (see Wiśniewski 2012: 121). For example, the subsidiary of Nuctech (a security scanning equipment manufacturer) in Poland also sells to Turkey; the subsidiary of Guangxi LiuGong Machinery in Poland targets the EU, North American and Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) markets, while Huawei’s logistic centre in Hungary supplies over 50 countries located in Europe and North Africa.

Based on the interview results, Chinese companies wanted to operate in ECE due to their already existing businesses in Western Europe and to strengthen their presence in the wider European market. In addition, there are also cases of Chinese companies following their customers to the ECE region, as in the case of Victory Technology (supplier to Philips, LG and TPV) or Dalian Talent Poland (supplier of candles to IKEA) (see McCaleb and Szunomár 2017: 125). Moreover, through their ECE subsidiaries, Chinese firms can participate in public procurements and access EU funds. As a case in point, Nuctech established its subsidiary in Poland in 2004, initially targeting mainly Western European markets, before focusing more on the ECE (CEE) region, which benefits from different EU funds. Recently, Chinese firms have also become interested in investing in the food industry as a result of the growing awareness about food safety standards and certificates. They are interested in exporting agricultural products which meet EU safety certificates to China where food safety causes problems. These factors lead us to the institutional host country determinants of the ECE region (Table 3.3).

As for supranational institutional factors, we can state that the change in the ECE countries’ institutional setting due to their economic integration into the EU has been the most important driver of Chinese outward FDI in the region, especially in the manufacturing sector. EU membership of ECE countries allowed Chinese investors to avoid trade barriers, and ECE countries could serve as an assembly base for Chinese companies. Moreover, not only actual EU membership but also the prospects of EU membership attracted Chinese investors to the region: thus, some companies made their first investments even before 2004, that is, in the early 2000s. New investments arrived in the year of accession, too. The second “wave” of Chinese FDI in CEE dates back to the global economic and financial crisis, when financially distressed companies all over Europe, including ECE, were often acquired by Chinese companies.

Another aspect of EU membership that has induced Chinese investment in the five ECE countries was institutional stability (including, e.g., the protection of property rights). This was important for early investors from Japan and Korea and was one of the drivers of FDI by Chinese firms, given the unstable institutional, economic and political environment in their home country. These findings are in line with those of Clegg and Voss (2012: 101), who argue that Chinese outward FDI in the EU shows “an institutional arbitrage strategy” as “Chinese firms invest in localities that offer clearer, more transparent and stable institutional environments. Such environments, like the EU, might lack the rapid economic growth recorded in China, but they offer greater planning and property rights security, as well as dedicated professional services that can support business development”.

National-level institutional factors include, for example, strategic agreements, tax incentives and privatization opportunities. The significance of such factors has begun to increase only recently as the majority of ECE countries—with the exception of Hungary—neglected relations with China in the early 2000s, starting to focus on the potentials of this relationship only since the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2008. Based on our observations as well as responses from interviewees, Chinese companies indeed appreciate business agreements that are supported by the respective host country government. Thus, the high-level strategic agreements with foreign companies investing in Hungary offered by the Hungarian government could have also spurred Chinese investment in the region. Moreover, personal (political) contacts between representatives of the respective host country government and Chinese companies also proved to be important when choosing a host country in the ECE region.

Based on the available literature, companies interested in acquiring foreign assets might be motivated by a common culture and language as well as trade costs (see Blonigen and Piger 2014; Hijzen et al. 2008). We also found that in the case of Chinese MNEs’ motives in the ECE region, a significant role is devoted to other less quantifiable aspects, such as the size and feedback of Chinese ethnic minority in the host country, investment incentives and subsidies, possibilities of acquiring visa and permanent residence permit, and the quality of political relations and government’s willingness to cooperate. A clear example for that is the stock of Chinese investment in Hungary, which is the highest in the ECE region (as well as in the broader CEE region).

Hungary is a country where the combination of traditional economic factors and institutional factors seems to play an important role in attracting Chinese investors. The country has historically had good political relations with China, established earlier than by other ECE countries. From 2003 onwards, the Hungarian government has intensified bilateral relations to attract Chinese FDI. Moreover, Hungary is the only country in the region that has introduced special incentives for foreign investors from outside the EU, that is, a “golden visa” programme which enables investors to acquire a residence visa in exchange for investing a certain amount of money. Moreover, Hungary has the largest Chinese diaspora in the region, which is an acknowledged attracting factor for Chinese FDI in the extant scientific literature—in other words, a relational asset that constitutes an ownership advantage for Chinese firms when they invest in countries with a significant Chinese population (see Buckley et al. 2007). An example for this is Hisense’s explanation of the decision to invest in Hungary which, besides traditional economic factors, was motivated by “good diplomatic, economic, trade and educational relations with China; big Chinese population; Chinese trade and commercial networks, associations already formed” (see CIEGA 2007).

4.2 The Role of Political Relations in Attracting Chinese FDI to the ECE Region: Friendship Factor?

In addition to the above-mentioned supranational- and national-level institutional pull factors, political relations between China and the respective ECE countries also seem to have influenced Chinese MNEs’ investment decisions. Those countries that have acted in favour of China, supported Chinese global and regional initiatives and/or welcomed and fostered Chinese MNEs’ investments typically host—or have hosted during the period of rather friendly ties—more Chinese FDI stock than those ECE countries that remained neutral over the opportunity to host Chinese FDI and/or where the political leaderships have a rather negative stance on China.

Hungary, for example, seems to be politically committed to China. In fact, Hungary was among the first countries to establish diplomatic relations with China (3 October 1949); since then, diplomatic gestures have been made and confidence-building measures taken from time to time. For instance, Hungary was the first European country to sign a memorandum of understanding with China on promoting the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road during the visit of China’s foreign minister Wang Yi to Budapest in June 2015. The Hungarian government was also very keen on promoting the Budapest-Belgrade railway, a long-negotiated soon to be started construction project under the Belt and Road umbrella. When signing the construction agreement in 2014, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán called it the most important moment for the cooperation between the EU and China (see Keszthelyi 2014). Supporting China’s infrastructural endeavour is, however, not the only field where Hungary excelled in exams. In 2016, Hungary (and Greece) prevented the EU from backing a court ruling against China’s expansive territorial claims in the South China Sea (see The Economist 2018), while in 2018, Hungary’s ambassador to the EU was alone in not signing a report criticizing the Chinese One Belt, One Road (OBOR ) initiative for benefitting Chinese companies and Chinese interests and for undermining principles of free trade through its lack of transparency in procurement (see Sweet 2018). In addition, as mentioned in the section above, it provided incentives for Chinese MNEs that have invested in the country. It has to be mentioned, though, that in the past few years the amount of Chinese FDI stock has been very slightly increasing in Hungary. The potential reason for that is China now focuses on infrastructure projects in the EU and the already mentioned Budapest-Belgrade railway project—if successfully implemented—would be a good base for reference when applying for other projects within the EU.

Starting from a rather cold and critical stance, Czechia’s relationship with China changed a few years ago. Since then, similar political factors—compared to the Hungarian case—have been observed in Czech-Chinese relations: after Czech “political sympathy” emerged, inflows of Chinese FDI to Czechia started to increase. As a case in point, the Czech president Milos Zeman—who was the only high-level European politician visiting Chinese celebrations of the end of World War II in 2015—declared that he wants his country to be China’s “unsinkable aircraft-carrier” in Europe (see The Economist 2018). Zeman also had a Chinese adviser on China, coming directly from a Chinese company with a controversial background. Moreover, as a potential result of the improving political relations, the Chinese company CEFC recently invested sizeable amounts—1.5 billion EUR—in Czechia. It has to be added, however, that this company is now under investigation by Chinese authorities for “suspicion of violation of laws” (see Lopatka and Aizhu 2018). As a result, Czech-Chinese relations have been cooling off again, and new Chinese FDI flows have not arrived since then; moreover, disinvestment has taken place in 2017 (see Figs. 3.5 and 3.6)

Slovakia can be currently perceived as one of the most pro-Western states in the region, particularly in terms of its relatively pro-EU stances, especially when compared with other Visegrád countries. As a result, Slovakia was more ignorant towards China during the past years, although it supported 16(17) + 1 and Belt and Road initiatives but with less enthusiasm and rather chose a “wait and see” approach. Similarly, Slovenian-Chinese relations have not received high priority on the political level, not even in the country’s foreign policy orientation. Besides, the former (2004–2008; 2012–2016) as well as current (2020–) prime minister, Janez Jansa, has a rather negative stance on China: previously (while in opposition) he met the Dalai Lama and travelled to Taiwan at the invitation of the government of the Republic of China. Consequently, Chinese investment into both Slovakia and Slovenia has relatively insignificant when compared to Chinese MNEs’ investments in the other three ECE countries.

Poland used to be more enthusiastic about the potentials of its economic relationship with China. Recently, however, the country has taken a more critical—or even cautious—stance. For Poland, high trade deficits represent the biggest problem with regard to the country’s bilateral ties with China: Poland imports from China goods to a value of some 12 times that of Poland’s exports to China, with the deficit reaching 20 billion EUR according to Eurostat. Potential security risks of Chinese investments caused the Polish government to reconsider its rather positive approach towards China and to use firm rhetoric about trade deficits as a serious political problem. This reconsideration was signalled, for example, by the cancellation of a tender in February 2018 for a land in Łódź where a transhipment hub was to be built and in which a Polish-Chinese company expressed interest. Another example was a government adviser’s statement in connection with the Central Communication Port, a current flagship project of the Polish government, saying that Chinese (party) financing in return for control over the investment would be rejected (see Szczudlik 2017). As a probable result of this, investment flows are stagnating in the past one or two years. Poland is, however, too big a market for China to completely turn back on it; therefore it is possible that Chinese MNEs will be more persistent there.

5 Conclusions

The rise of Chinese multinationals is a new and dynamic process, while their approach towards their host economies is relatively unique compared to more developed MNEs. This chapter presented the main features of Chinese outward FDI globally, focusing both on push and pull factors behind the international expansion strategies of Chinese MNEs.

As presented in the above sections, initially the Chinese government had promoted outward FDI mainly to secure access to natural resources, while later market-seeking and efficiency-seeking motivations started to become important too. More recently the desire to acquire new technologies and managerial experience also came to the fore. The Chinese government has promoted and guided outward FDI with the main aim of acquiring assets that were scarce in the country or considered as crucial for further development of the domestic economy. With this objective it has mainly focused on the dynamic comparative advantages available in the host countries. Chinese MNEs’ motivations for investment, however, vary from host country to host country: Chinese outward FDI in emerging or developing countries is characterized more by resource-seeking motives, while Chinese companies in the developed world are rather focusing on buying themselves into global brands or distribution channels, getting acquainted with local management skills and technology. Regarding modes of entry, investments shifted from greenfield projects to M&As, which represent currently around two-thirds of all Chinese outward FDI in value. This shift is driven by the financial crisis; however, it also seems to be a new trend of Chinese FDI to the developed world, while greenfield investment remains significant in the developing world. Outward FDI has also become more diversified in the past years: from mining and manufacturing it turned towards high technology, infrastructure and heavy industry, and lately to the tertiary sector, business services and finance but also health care, media and entertainment.

On the home country side, the Chinese government has pursued both proactive and interventionist strategies at the same time to promote the international expansion of Chinese companies in various sectors. This feature—that is, the prominent role of the state in initiating and intervening in corporate capital outflows—seems to be a distinctive element in the behaviour of Chinese MNEs when compared to multinational corporations of developed countries. These national champion companies were either state-owned or state-backed private firms that have benefitted from government subsidies and for a shorter or longer period of time were protected from—domestic as well as foreign—competition.

Asia continues to be the largest recipient of total Chinese outward FDI, accounting for nearly three-quarters, followed by the EU, Australia, the US, Russia and Japan. The numbers might be misleading though due to round-tripping investments. According to project-level analysis, 60 per cent of Chinese outward FDI is aimed at developed economies. As for Chinese MNEs’ FDI to the EU, Chinese investors have preferred “old European” investment destinations not only because of market size but also because of well-established and sound economic relations with these countries.

The decline in Chinese outward FDI flows is relatively significant in the past few years; however, Chinese companies are still spreading and expanding in Europe, which often results in scrutiny and caution in some of the European countries as well as on the EU level. Chinese greenfield investments and acquisitions are perceived—especially but not exclusively by Western European governments—to threaten the competitiveness, strength and unity of Europe, both economically and politically. However, in Eastern and Southern Europe, where China is engaging within the so-called 16(17) + 1 framework, some of the countries rather welcome than fear Chinese FDI transactions.

Chinese investment in ECE countries constitutes a small share in China’s total FDI stock, even if compared to Chinese total FDI stock in Europe, and is quite a new phenomenon. Nevertheless, Chinese FDI in the ECE region is on the rise and may increase further due to recent developments between China and certain countries of the region, especially Hungary. The analysis of the motivations behind Chinese outward FDI in ECE shows that Chinese MNEs mostly search for markets. ECE countries’ EU membership allows them to treat the region as a “back door” to the affluent EU markets; moreover, Chinese investors are attracted by the relatively low labour costs, skilled workforce and market potential. It is characteristic that their investment patterns in terms of country location resemble that of the world’s total FDI in the region.

As demonstrated in the analysis above, macroeconomic or structural factors do not fully explain the decisions behind Chinese FDI in the broader CEE region, including ECE countries. For example, Hungary, Czechia and Poland, the three largest recipients of Chinese investment in CEE, are not the most attractive locations either in terms of cutting costs or when searching for potential markets in the broader CEE region. This indicates that institutions may be crucial for Chinese companies when deciding on investment locations. In order to map out the real significance of such institutional factors, these were divided into two levels: the supranational level and the national level. Supranational institutional factors that attract Chinese companies to the ECE region are linked to the EU membership (economic integration) of ECE countries, especially to the institutional stability provided by the EU. Country- or national-level institutional factors that impact location choice within ECE seem to be privatization opportunities, investment incentives, such as tax incentives, special economic zones, “golden visas” or resident permits in exchange for a given amount of investment, and the size of the Chinese ethnic population in the host country.

Although we could not find clear evidence for causal links between the level of political relations and the amount of Chinese investment in ECE countries, good political relations between the respective host country and China seem to play an important role in attracting investment from Chinese state-owned as well as private companies. Examples are (1) Hungary’s good political relations with and strong political commitment to China, while hosting the biggest stock of Chinese FDI in the ECE and the broader CEE region; (2) the positive political shift in Czech-Chinese relations that induced increasing amounts of Chinese FDI in Czechia; (3) stagnating stock of FDI in Poland as a result of a more critical stance on China and (4) the parallel between the lack of real interest to host Chinese MNEs from Slovakia and Slovenia and the low levels of Chinese FDI stock in these countries.

In order to investigate the topic in far more detail and find clear evidence on the existence of a political factor—or a “friendship factor”—among pull factors for Chinese FDI in the ECE region, a further possible step could be firm-level in-depth interviews with the officials of the most important Chinese companies that have invested in the ECE region, as well as personal interviews with government officials and business organizations in these countries.

Notes

- 1.

The ten per cent threshold is traditionally required for a transaction to qualify as FDI. Transactions that fall under the ten per cent threshold are usually qualified as portfolio investments and are not included in majority of the FDI datasets.

- 2.

The non-EU member Switzerland hosts the biggest amount of Chinese FDI stock in Europe. In 2018 it reached 18,084 million USD according to OECD Statistics.

- 3.

Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia joined in 2004 and Bulgaria and Romania in 2007.

- 4.

Countries in the Balkans have not received so far big amounts of FDI from China, despite some of them being EU members and others potential candidates. Romania, Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria are the major recipients in the Balkan region; they host 80 per cent of the Chinese FDI stock in the Balkans (still, it is just one quarter of the Chinese FDI stock in the Visegrád region). Based on Chinese statistics, countries such as Albania and Bosnia and Herzegovina seem not to attract any significant Chinese FDI at all (both data are below 10 million USD), while North Macedonia, Montenegro, Slovenia and Croatia also host less than 100 million USD Chinese FDI stock.

- 5.

References

Amendolagine, V., & Rabellotti, R. (2017). Chinese Foreign Direct Investments in the European Union. In J. Drahokoupil (Ed.), Chinese Investment in Europe: Corporate Strategies and Labour Relations (pp. 99–120). Brussels: ETUI.

Blonigen, B. A., & Piger, J. (2014). Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment. Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(3), 775–812.

Buckley, P. J., Clegg, L. J., Cross, A. R., Liu, X., Voss, H., & Zheng, P. (2007). The Determinants of Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4), 499–518.

Caseiro, L., & Masiero, G. (2014). OFDI Promotion Policies in Emerging Economies: The Brazilian and Chinese Strategies. Critical Perspectives on International Business, 10(4), 237–255.

CIEGA. (2007). Investing in Europe. A Hands-on Guide. Retrieved November 4, 2016, from http://www.e-pages.dk/southdenmark/2/72.

Clegg, J., & Voss, H. (2012). Chinese Overseas Direct Investment in the European Union. Retrieved August 17, 2017, from http://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Asia/0912ecran_cleggvoss.pdf.

Davies, K. (2013). China Investment Policy: An Update. OECD Working Papers on International Investment. 2013/01. OECD Publishing. Retrieved August 17, 2017, from https://doi.org/10.1787/5k469l1hmvbt-en.

Di Minin, A., Zhang, J. Y., & Gammeltoft, P. (2012). Chinese Foreign Direct Investment in R&D in Europe: A New Model of R&D Internationalization? European Management Journal, 30, 189–203.

Dunning, J., & Lundan, S. M. (2008). Institutions and the OLI Paradigm of the Multinational Enterprise. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 25(4), 573–593.

Hanemann, T. (2013, January 27). The EU-China Investment Relationship: From a One-way to a Two-way street. New Europe Online. Retrieved August 17, 2017, from http://www.neurope.eu/kn/article/eu-china-investment-relationship-one-way-two-way-street.

Hanemann, T., & Huotari, M. (2017). Record Flows and Growing Imbalances – Chinese Investment in Europe in 2016. MERICS Papers on China, No 3. Retrieved October 15, 2017, from https://www.merics.org/fileadmin/user_upload/downloads/MPOC/COUTWARDFDI_2017/MPOC_03_Update_COUTWARD FDI_Web.pdf.

Hanemann, T., Huotari, M., & Kratz, A. (2019). Chinese FDI in Europe: 2018 Trends and Impact of New Screening Policies. Rhodium Group (RHG) and the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS). Retrieved from https://www.merics.org/en/papers-on-china/chinese-fdi-in-europe-2018.

He, F., & Wang, B. (2014). Chinese Interests in the Global Investment Regime. China Economic Journal, 7(1): 4–20. Retrieved October 15, 2017, from https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2013.874067.

Hijzen, A., Görg, H., & Manchin, M. (2008). Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions and the Role of Trade Costs. European Economic Review, 52(5), 849–866.

Hymer, S. H. (1976). The International Operations of National Firms: A Study of Direct Foreign Investment. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Irwin, A., & Gallagher, K. P. (2014). Exporting National Champions: China’s Outward FDI Finance in Comparative Perspective. GEGI Working Paper, Boston University, June 2014, Paper 6. Retrieved from http://www.bu.edu/pardeeschool/files/2014/11/Exporting-National-Champions-Working-Paper.pdf.

Keszthelyi, C. (2014). Belgrade-Budapest Rail Construction Agreement Signed. Budapest Business Journal, December 17.

Kostova, T., & Zaheer, S. (1999). Organizational Legitimacy Under Conditions of Complexity: The Case of the Multinational Enterprise. Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 64–81.

Lopatka, J., & Aizhu, C. (2018). CEFC China’s Chairman to Step Down; CITIC in Talks to Buy Stake in Unit. Reuters, March 20. Retrieved November 28, 2018, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-cefc-czech/cefc-chinas-chairman-to-step-down-citic-in-talks-to-buy-stake-in-unit-idUSKBN1GW0HB.

Luo, Y., Xue, Q., & Han, B. (2010). How Emerging Market Governments Promote Outward FDI: Experience from China. Journal of World Business, 45(1), 68–79.

Madhok, A., & Keyhani, M. (2012). Acquisitions as Entrepreneurship: Asymmetries, Opportunities, and the Internationalization of Multinationals from Emerging Economies. Global Strategy Journal, 2(1), 26–40.

McCaleb, A., & Szunomár, A. (2017). Chinese Foreign Direct Investment in Central and Eastern Europe: An Institutional Perspective. In J. Drahokoupil (Ed.), Chinese Investment in Europe: Corporate Strategies and Labour Relations (pp. 121–140). Brussels: ETUI.

MOFCOM (2004): Foreign Trade Law of The People’s Republic of China. Available at: http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/aarticle/policyrelease/internationalpolicy/200705/20070504715845.html.

Morrison, W. M. (2013). China’s Economic Conditions. CRS Report for Congress. Retrieved August 15, 2017, from http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/crs/rl33534.pdf.

Muralidhaara, G. V., & Faheem, H. (2019). Huawei’s Quest for Global Markets. In China Europe International Business School (Ed.), China-Focused Cases. Singapore: Springer.

Naughton, B. (2007). The Chinese Economy: Transitions and Growth. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Nölke A., Ten Brink T., Claar S., May C. (2015): Domestic structures, foreign economic policies and global economic order: Implications from the rise of large emerging economies. European Journal of International Relations 2015, Vol. 21(3) 538–567.

Peng, M. W. (2012). The Global Strategy of Emerging Multinationals from China. Global Strategy Journal, 2, 97–107.

Ramachandran, J., & Pant, A. (2010). The Liabilities of Origin: An Emerging Economy Perspective on the Costs of Doing Business Abroad. In T. Devinney, T. Pedersen, & L. Tihanyi (Eds.), The Past, Present and Future of International Business and Management (pp. 231–265). New York: Emerald Group Publishing.

Rosen, D. H., & Hanemann, T. (2009). China’s Changing Outbound Foreign Direct Investment Profile: Drivers and Policy Implications. Policy Brief – Peterson Institute for International Economics, PB09-14. Retrieved August 15, 2017, from http://www.iie.com/publications/pb/pb09-14.pdf.

Sass, M., Szunomár, Á., Gubik, A., Kiran, S., & Ozsvald, É. (2019). Employee Relations at Asian Subsidiaries in Hungary: Do Home Or Host Country Factors Dominate? Intersections: East European Journal of Society and Politics, 5(3), 23–48.

Sauvant, K. P., & Chen, V. Z. (2014). China’s Regulatory Framework for Outward Foreign Direct Investment. China Economic Journal, 7(1), 141–163.

Scissors, D. (2014). China’s Economic Reform Plan Will Probably Fail. Washington, DC: AEI. Retrieved August 15, 2017, from https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/-chinas-economic-reform_130747310260.pdf.

Sweet, R. (2018). EU Criticises China’s ‘Silk Road’, and Proposes Its Own Alternative. Global Construction Review, May 9. Retrieved November 28, 2018. from http://www.globalconstructionreview.com/trends/eu-criticises-chinas-silk-road-and-proposes-its-ow/.

Szczudlik, J. (2017). Poland’s Measured Approach to Chinese Investments. In J. Seaman, M. Huotari, & M. Otero-Iglesias (Eds.), Chinese Investment in Europe – A Country-Level Approach. ETNC Report, December.

Szunomár, Á. (2017). Driving Forces Behind the International Expansion Strategies of Chinese MNEs. IWE Working Paper 237.

Ten Brink, T. (2013). Chinas Kapitalismus. Entstehung, Verlauf, Paradoxien / China’s Capitalism: Emergence, Trajectory, Paradoxes. Frankfurt; New York: Campus.

The Economist. (2018). China Has Designs on Europe. Here Is How Europe Should Respond. Print Edition of 4 October, 2018.

UNCTAD. (2013). Global Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development. United

Wang, B. (2013). A Misread Official Data: The True Pattern of Chinese ODI. International Economic Review (GuoJi Jing Ji Ping Lun) 2013/1, pp. 61–74.

Wiśniewski, P. A. (2012). Aktywność w Polsce przedsiębiorstw pochodzących z Chin [Activity of Chinese Companies in Poland]. Zeszyty Naukowe, 34. Kolegium Gospodarki Światowej, SGH, Warszawa.

Witt, M. A., & Redding, G. (2013). Asian Business Systems: Institutional Comparison, Clusters and Implications for Varieties of Capitalism and Business Systems Theory. Socio-Economic Review, 11(2), 265–300.

Zhang, Y., Duysters, G., & Filippov, S. (2012). Chinese Firms Entering Europe: Internationalization Through Acquisitions and Strategic Alliances. Journal of Science and Technology Policy in China, 3(2), 102–123.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Szunomár, Á. (2020). Home and Host Country Determinants of Chinese Multinational Enterprises’ Investments into East Central Europe. In: Szunomár, Á. (eds) Emerging-market Multinational Enterprises in East Central Europe. Studies in Economic Transition. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55165-0_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55165-0_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-55164-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-55165-0

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)