Abstract

This chapter revolves around how ethical tensions confront researchers at each stage of research. It refers to ‘pre-research phases’ where particular attention needs to be paid to anonymity/confidentiality and informed consent. During ‘data collection’ and ‘analysis’, care of participants and researcher self-care go together, and there is a need to manage emotional intensity and power relations. Following this, the ‘writing up and dissemination phases’, research integrity and care of wider communities are prioritised, prompting a new need for ethical sensitivity–often guided by reflexivity and a need to handle each individual situation, and the complex relational dynamics involved, as they arise in context. This often means that what may seem responsible, respectful and caring to one person may not to another. The chapter explores how to negotiate an ethical path where often tricky decisions and compromises may need to be made. The trustworthiness and integrity of the research must, in this sense, be balanced by respect and concern for the well-being of participants, researchers and wider communities. The chapter refers to the challenge of making ethical judgements with care, humane intention, reflexivity and as much conscientiousness as researchers can summon.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

-

Describe the ethical requirements arising in the planning and contracting phase of research, including managing confidentiality/anonymity and informed consent;

-

Critically analyse the challenges posed by emotional intensity and power relations during data collection;

-

Appreciate the need for researchers to attend to their own self-care;

-

Discuss the ethical value of participant validation (or member checking) to ‘prove’ the validity of the research;

-

List at least four potential risks of doing research on clients’ experiences of therapy;

-

Explain how researchers can take responsibility for their research and ensure the research has integrity.

Knotty Situations in Research

There are several kinds of knotty situations we regularly experience once we dig below the surface of ethics.

► Example

Peter has volunteered to be a participant in Vineeta’s phenomenological study of the lived experience of being adopted. As the interview progresses he starts to sob as issues of feeling abandoned and not belonging surface. Vineeta feels torn. Their conversation has moved into an area which would add valuable dimensions to her data but she also recognises how Peter’s welfare is paramount.

How should this researcher handle the dilemma confronting her: that the very act of collecting her research data makes Peter, her participant, dissolve into tears? At what point should the recorder be turned off or the interview ended? The researcher is caught in a balancing act in which the needs and integrity of the research become set against responding to Peter’s needs. Was she aware that he might become distressed and does she have the right to use this situation for her own research ends?

Professional guidelines on the ethical conduct of research are based on certain core principles: a concern to promote scientific integrity; an awareness of social responsibility; and respect for individuals’ autonomy, privacy, values and dignity. To show a duty of care that maximises benefit and minimises risks or harm to individuals, researchers are asked to ensure confidentiality/anonymity and informed consent. Care is taken to brief and debrief participants, who are informed of their right to withdraw from the research if they so choose.

When we present our research, we lay claim to these guidelines and through them assert the ethical integrity of our work. In practice, however, every research encounter brings up context-specific ethical challenges. What may seem responsible, respectful and caring to one person may not to another. It depends. Negotiating an ethical path can often be tricky and compromises may need to be made (Finlay and Molano-Fisher 2009). Ethics then can be understood as ongoing reflexivity (critical self-awareness) of our research actions, thoughts and motivations (Finlay 2019).

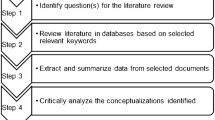

This chapter sketches some of the ethical tensions confronting us as researchers at each stage of a research project, drawing on different research examples. It starts by considering key ethical requirements of the pre-research planning stage. The next two sections explore the data collection and analysis phases. A final section looks at the challenges involved in writing up and disseminating the research. Most of the discussion relates especially to qualitative research given the unpredictable situations and complex dynamics usually involved. The aim is to get you thinking reflexively and ethically about the requirements of your own research….

Pre-research Phase

Research usually begins with a researcher’s passionate concern to learn something more about a subject. Then comes the time-consuming planning process, where researchers work out how to operationalise the research. Often this involves a process of gaining ‘official’ ethics approval before any research can begin. There may even be the need to convince a formal independent Research Ethics Committee of the value and ethical rigour of the research.

But getting a proposal through an ethics approval process doesn’t ensure that the research will be ethical. It’s the ongoing process in which we engage that determines ethicality. Beyond procedures, it’s about attending to the research context and relationship (Guillemin and Gillam 2004).

Perhaps the biggest challenge is drawing up the research agreement we use when meeting prospective participants. Often this takes the form of a written contract participants are asked to sign and date if they agree to participate in the research. As with contracting for counselling/psychotherapy, there are many issues to consider, including:

-

Aims of the project

-

Criteria for inclusion

-

Informed consent (including ‘process consent’)

-

Participant–and researcher–safety/risk

-

Confidentiality and anonymity (including limits)

-

How participants will be briefed, debriefed and/or given support if needed

-

Division of labour and responsibilities of both researcher and participant (including involvement in subsequent research phases)

-

Participant’s right to withdraw from the study (including date beyond which they cannot withdraw)

-

Storage and disposal of participant information and data (and General Data Protection Regulation [GDPR]).

A delicate balancing act is involved as we seek to set boundaries and establish mutual trust. What will work for one person or project may not be suitable in other situations. Two particularly knotty areas are confidentiality/anonymity and informed consent.

Confidentiality/Anonymity

As with confidentiality in therapy, a key ethical principle of research is that data will be treated respectfully, with attention paid to confidentiality, anonymity and data protection. Yet complications can arise, and there may be times when legal and safeguarding issues emerge.

More commonly, random details revealed in findings might mean participants can be identified. Below, two researchers discuss how they approached the ethical issues involved in conducting their study:

Because of the highly sensitive nature of the information disclosed during the interviews special precautions were adopted. The possibility, however remote, that the therapists and the clients they discussed in their vignettes could be identified was a particular concern. All demographic and descriptive information about therapists was minimized and kept at a group level. In order to protect the participants’ privacy, pseudonyms were used and any information that would make them susceptible to identification was omitted or deliberately made vague. (Thériault and Gazzola 2006, p.317)

In some situations, we might go beyond simply keeping details vague to changing participants’ demographic details to further camouflage their identity. For example, I might say my participant lives in England when they live in Scotland; or I might change the sex or profession of the participant. While lying is unethical, concealing the truth may at times be necessary to preserve a participant’s anonymity.

In legal terms, the removal of identifying information means that the data is no longer considered ‘personal’ and as such does not fall under the GDPR. However, it may not always be possible to fully de-identify data, and participants should be informed of how their data will be anonymisedFootnote 1 so that they can make an informed decision about consent for its storage and sharing (for further information about the GDPR, see the document from the British Psychological Society (2018): Data Protection Regulation: Guidance for researchers).

The researchers above used pseudonyms, the most common way of de-identifying data. However, I’ve done some research where participants wanted their contribution acknowledged. Mindful of this, I now always ask participants to choose the name they wish to go by. Although participants can also be allocated numbers, I regard letting them choose a name more as humanising.

One final tip for data protection is ‘data minimisation’: keeping the details about personal data to a minimum. Not every survey or research study needs to collect data about participants’ age, sexuality or ethnicity.

Informed Consent

Informed consent in research means ensuring that participants know about their rights and understand what is expected of them. However, in qualitative research we rarely know in advance how the exploration will proceed and what will be ‘unearthed’. In this situation, how can a participant give ‘informed consent’?

This is where ethical, reflexive practice becomes imperative. We need to involve participants in an ongoing consent process in which we keep checking to see if they are okay with how the research is going and negotiate how best to proceed–relationally. Just as we do in therapy, we must regularly review the research agreement and check that the participant is prepared to continue.

Often researchers give participants the option of withdrawing from the research after they’ve had a chance to think about their contribution. It’s good practice to make it clear to participants at the outset the date or stage after which they cannot withdraw. I know of a student whose participant asked to be withdrawn after she had handed in her project, creating considerable turmoil for all.

The examples below demonstrate the need to be careful when obtaining consent. The first is a reflexive dialogue between Kim Etherington (2007) and two co-researchers/participants who were her ex-clients.

► Example

Narrative inquiry and ethics

You will have read parts of this in-depth discussion in ► Chap. 5 where Etherington expands on this research. The following is a continuation from this relational negotiation of interest (Etherington 2007).

Kim: The process of doing this may very well open up things again, and I wonder what that would be like for you…

Stephen: I feel like I’m ready for that, I think I could cope with that now – at a distance. I could deal with that now.

Kim: How about you Mike?

Mike: [Pause] Mmm. Yes, I think so. I think I’ve demonstrated by recent events [his separation from his wife] that I can mobilize support if I need to.

Kim: But here we are now, moving into a different relationship, when I’m not your counselor. What would that mean if anything did come up? What might be your expectations of me if you got very distressed about something that was happening as part of the research process? I suppose my concern is – that if you needed counseling – I don’t think it would be appropriate for me to offer that.

Stephen: That would be OK.

Kim [to Stephen]: But I am also aware that you have financial limitations that would make it hard for you to get counseling elsewhere. I just wondered if you had thought about that…There are other agencies where you can go for low-fee or reduced-fee counseling… That’s not to say that I didn’t expect this to be therapeutic, or, that I’m not going to be able to be supportive as a researcher. (pp. 606–607).

The second example is from Morrow’s (2006) feminist collaborative research with sexually abused women.

► Example

Morrow (2006) refers to how the process of gaining consent circumvented her control over data collection:

I had originally planned to meet for a short time with each interviewee to explain the project, get acquainted, explain and have participants sign the informed consent form and schedule our longer interview. I had explained this expectation to the first participant, Paula, when we first made telephone contact. However, after we had finished the informed consent process and I pulled out my calendar to schedule our interview appointment, she objected, saying, ‘I thought we were going to do the interview now. I’m ready to talk!’ I consented and, feeling a little panicky, searched for my interview guide. Unable to find it, I finally responded,

‘Well, uh, er, um. Tell me, as much as you are comfortable sharing with me right now, um, what happened to you when you were sexually abused.’ This kind of question, both very personal and potentially disturbing for a participant, is not the kind of question with which I would normally begin an interview, but Paula’s desire to tell her story and my own personal style (I’ve been described as an ‘earth mother’ who elicits trust very early in a relationship) converged to make the question both appropriate and effective (p.153).

Here, Morrow indicates that she placed her ethical concern for her co-researchers above her research strategy. The significant step demanded of the relationally minded researcher is to release control, or rather take “control in a new humanistic sense by being clearly conscious of the choice of letting the informant have a voice” and to lay the ground for an open, authentic, mutual interaction (Kruger 2007).

Having gained ethical approval for a project, worked satisfactorily with official gatekeepers and then negotiated the appropriate consent, some researchers are content that they’ve gone through the required ethics hoops. However, ethics doesn’t stop here. An ethical sensibility is needed at every stage of research.

Data Collection Phase

Professionally orientated research frequently uses data on sensitive areas of human experience: health, life experience and personal disclosure. With qualitative research, we might also aim to ‘witness’ and/or ‘give voice’ to our participants’ experiences. We need to be mindful that research which encourages participants to reflect on themselves and the social world around them may evoke strong emotional responses. In such a context, risk assessment is complicated, and questions arise regarding emotional intensity and unequal power relationships.

Emotional Intensity

Emotional intensity in the data collection phase raises challenging issues. At what point should a participant be deemed ‘at risk’? If a participant becomes irritated or offended, or feels uncomfortable while doing a survey, does that constitute ‘harm’? If a person grows upset during an interview, is that a problem? Should researchers avoid tackling potentially emotive topics (something that goes against the very grain of our research curiosity)? And what if participants actually welcome the opportunity to talk at a deep, personal level and be ‘seen’? For them, it’s possible that getting upset may be a relief rather than a ‘problem’; it may even be therapeutic. How we manage emotional intensity goes to the heart of negotiated ethics.

I collaborated with my friend/colleague Pat about her lived experience of receiving a cochlear implant (Finlay and Molano-Fisher 2008). I not only heard a story about new hearing and well-being, I also saw close-up her struggle with deafness and disability. Profoundly deaf for much of her life, after her implant Pat found herself in a surreal, alien world filled with hyper-noise. Over the course of the following year her life was turned upside down. She slowly learned new ways to connect with her world, but at a psychological and social level her relationships with others changed and part of her felt more disconnected than before. Loss of confidence, shame, alienation and isolation were some of the emotional themes which surfaced repeatedly. In the following extract from our interview, Pat expresses embarrassment about her disability:

Pat: My sense of confidence is battered…How many mistakes have I made in my work and interactions? I cringe when I think about it.

The fact that our research tapped sensitive emotions made me worry whether our project of probing her lived world was forcing Pat to face her pain more than she would have otherwise. At times Pat seemed angry; her vulnerability was highlighted, and we had to work through that (Finlay and Molano-Fisher 2009).

In other words, there are no clear-cut answers about what level of disclosure or degree of restraint is desirable in relational research. Negotiations can only take place within the relationship, always with awareness of the power we wield as researchers.

The solution, says Krüger (2007), “lies within the relation itself”. In a sense the researcher needs to be “aware of the obligation to stay in the impasse, and at the same time to situate the problem where it belongs: in the relationship”. Here Kruger comes close to taking a therapeutic approach, highlighting the ethical value of working dialogically.

Power

Research asks people “to take part in, or undergo, procedures that they have not actively sought out or requested, and that are not intended solely or even primarily for their direct benefit” (Guillemin and Gillam 2004, p. 271). More than this, research is inherently instrumental and uses participants for researcher benefit. Is there a way this unequal power relationship can be owned and managed with ethical sensibilities to the fore?

The examples above in this section all implicitly grapple with the power dimension inherent in data collection. We don’t even need to think in extremes of manipulation and coercion. Researcher instrumentality is exposed at a simple level when (metaphorically speaking) we don the ‘white coat’ of the scientist and ask probing, intrusive, private questions while not disclosing ourselves. At a subtler level, the researcher is the one who uses ‘expert’ knowledge/techniques (such as using empathetic responses and reflecting back) to both open up participants and close them down again. Alert to opportunities to obtain data, we may push hungrily ahead instead of attending to participants’ needs. A key question to ask of your research is: “Whose interests are being served?” (Finlay and Ballinger 2006).

However, as we know from our therapy work, power is not clear-cut or one-way, with researchers having power and participants being powerless. Instead, there’s a complex interplay of structural dimensions: social position, race, gender and ethnicity. A young black female novice researcher-student may not feel any researcher power and authority when interviewing an older, white, male professor who is being dismissive of her research efforts. Power is layered, comes in different guises and is enacted between people in particular contexts. We need to be alert to how different types of power cross-cut each other and impact our research.

► Example

In the following example, Hunt (1989) discusses how her status as an unwanted female outsider studying police organisations raised some unexpected gender issues:

Positive oedipal wishes…appeared mobilized in the fieldwork… The resultant anxieties were increased because of the proportion of men to women in the police organization and the way in which policemen sexualized so many encounters…The fact that I knew more about their work world than their wives also may have heightened anxiety because it implied closeness to subjects. By partly defeminizing myself…I avoided a conflictual oedipal victory. (p.40).

Here, Hunt ‘defeminized’ herself to circumvent being sexualised. This seems to be an attempt to minimise her impact on the participants’ lives, but it may also have increased her authority. In other situations, we might want to do more to equalise our relationship. However, it is also not enough for researchers to relinquish some of their ‘power’ in favour of their participants. Efforts to ‘empower’ our participants may be misplaced, since we’re still claiming power to control access to power. Instead, it’s important to keep the communication channels open; be reflexive, acknowledge any emotional and political tensions arising from different social positions, and (where relevant) deconstruct the “researcher’s authority” (Hertz 1997).

Personally, I believe that Proctor’s (2002) reasoning about our use of power as therapists can equally be applied to research:

The ethical challenge in psychotherapy is to minimise the therapist’s potential to violate the other through therapy…this is the potential violence of theory, authority, expertise and technology to override the client’s contribution to their life narrative (p.60).

At its best, data collection can be both strategic and sensitively respectful. Here, the power within it emerges as an ongoing, mutual, interactive relationship where individuals exert degrees of agency, choice and control. As with therapy, we attempt a balancing act: we seek to enable and facilitate disclosure while at the same time intervening to protect our participants from too much exposure. Such “dialectical oppositions” (Ellis 2007, pp.20–21) involve moving back and forth between expression and protection, between disclosure and restraint (Bochner 1984). More than this, we need to be sensitive and recognise the importance of the relational context. Ellis (2007) sums this up well:

Relational ethics requires [therapists]… to act from our hearts and minds, acknowledge our interpersonal bonds to others, and take responsibility for actions and their consequences. (p.3).

Data Analysis Phase

The analytical phase of research raises ethical issues relating to the integrity of the research. Another question which confronts (particularly qualitative) researchers is the extent to which participants can/should be involved in producing, or at least validating, the findings. The respective roles of researcher and participant may need to be carefully negotiated, and careful thought needs to be given to the degree of participant involvement in validating results. The researcher also needs to attend to their own self-care.

Research Integrity

Research integrity refers to the moral character of the research. Has it been done in a way that allows others to have trust and confidence in the methods and findings, and in subsequent publications? Is there a commitment to intellectual honesty and regard for the scientific record? Does the researcher take personal responsibility for their research actions? Such values are important for both qualitative and quantitative research, despite varying criteria for what makes a study ‘trustworthy’. With qualitative research, trustworthiness is often displayed by methodological transparency and reflexivity (i.e. critical self-awareness). With quantitative research, trustworthiness is equated with scientific rigour and the use of both valid measurement tools and appropriate statistical tests. In all research there is a need for any interpretations to be set in context.

A key issue for quantitative researchers is the degree to which data might be falsified and/or subsequent analysis manipulated. (There is some truth to the phrase attributed to the British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli: “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.”) The trouble comes when researchers, keen to promote a position, ‘massage their data’ by taking out rogue or disconfirming bits so that the results fit their hypothesis or argument. They also might misrepresent their research by omitting key elements (e.g. an insufficiently representative sample). Or they might mislead by presenting results divorced from the larger context in which sense can be made of them.

Distortion can also occur at the very start of the research process, when researchers seeking an empirical rationale for their proposal assert that ‘little or no research exists in the field’ when a closer look says otherwise. Here, they are disrespectfully misrepresenting the work of others in order to shine a brighter light on their own.

Then there are those rarer cases of outright dishonesty and fraud where spurious results are fabricated. A colleague once told me about a student of hers who had produced some suspicious survey results. Initially, the student’s sample contained only 25 participants, which did not offer statistically meaningful results. After just two days the number of participants had tripled. The tutor was concerned to see that all the new data seemed to say implausibly similar things, all supportive of the student’s hypothesis, and that they all emanated from the same IP address.

A few high-profile historical cases of research fraud have been unearthed. In the field of educational psychology, Cyril Burt’s case was particularly grave. He both manipulated and fabricated the research data in his study of twins to enable him to confirm his theory of the heritability of intelligence. It turns out that many of his twins did not exist; nor did some of the research collaborators he talked about.

Deception–at whatever level–within psychological research occurs with the pressure to publish, both to gain personal/professional status and to please stakeholders, putting grant money to good use (Lilienfeld 2017). Given these pressures, there is an ever-present need for care and critical awareness, alongside continued vigilance and monitoring of our research processes.

Negotiating Respective Roles

Professionally orientated researchers often confront the question of how transparent they should be with participants about research findings. To some extent this depends on the methodology involved. With qualitative discourse analysis, for instance, participants are unlikely to get involved given its highly technical nature. Discursive methods tend to “utilise counter-intuitive, and possibly impenetrable, understandings of subjectivity which participants may reject”, not least because the participant’s sense of lived experience can be undermined (Madill 2009, p.20). While these researchers usually carry out their analysis on their own, the process of identifying and naming discourses still involves ethical, moral and political choices on the part of the analyst (Parker 1992). For this reason, discursive researchers are encouraged to be reflexive about how they position themselves and their participants within the social world.

In contrast, collaborative and participatory action forms of qualitative research rely on the process of iteratively taking evolving understandings back to participants. Halling et al. (1999) suggest a kind of collaborative approach where the analysis is conducted through group members’ dialogue. Their dialogical phenomenological study of forgiveness saw them collaborate with a group of Masters’ students, with positive results:

Working in dialogue and comparing personal experiences and the interviews with each other allowed us to come to a rich, collective understanding of the process of forgiving another… Freedom infused the process with a spirit of exploration and discovery, and is evident through the group members’ ability to be playful and imaginative with their interpretations. Trust provides the capacity to be genuinely receptive to what is new and different in the others’ experiences. (1999, pp. 253, 261).

While Halling et al. are committed to the fullest possible collaboration with co-researchers, others involve their participants only to the extent that the latter wish to be involved. With Pat and the cochlear implant research (Finlay and Molano-Fisher 2008), for example, we put effort into managing a division of labour. We decided we were both responsible for co-creating Pat’s narrative. But I wanted to engage a more in-depth existential phenomenological analysis, not least because I was due to present these findings (with Pat’s consent) at a conference. However, Pat was in a different place. She was finding her new implant difficult to cope with and was not ready to engage further analysis. We had to set the research aside for a few months, which later required a delicate process of re-contracting/process consent. I had to gauge when to gently nudge Pat to engage once more (or perhaps to disengage fully while giving me authorial control). I also had to be prepared to end the research.

► Example

Below is an extract from my reflexive diary (Finlay and Molano-Fisher 2008) indicating the questions I was asking:

There’s the issue of control and who has it. How ethical/acceptable is it for me to lead, reassure, persuade, convince, and in the process take more control? I don’t want to take Pat’s sense of control away. Yet are there dangers in my being too passive? Have I got the energy for this? (LF diary).

Later Pat contacted me, and we exchanged emails:

Pat: Hi Linda. I am ready again, sorry about long time, thanks for the space… couldn’t handle the analysis. Felt I wanted to move on, not to dwell in the past…

Linda: It’s understandable you want to move on – totally understandable. Rest assured that you don’t need to do any more with the analysis if you don’t want to... Let me know how you want to proceed… I want to understand more what is scaring you if you feel able to talk…

Pat: What scares me is that I don’t want to face deafness, disability, implants anymore...I don’t like that I cannot follow things like others do even with the implant. It scares me that I really like my silence and miss it…Even if I have progressed, I feel I will never feel ‘normal’ as I felt before because my bubble has been burst!! …I am scared about what else I don’t know will come in the analysis and I rather hide it and don’t face it!...

Pat eventually agreed to me doing the analysis, but she wanted to see and comment on everything (claiming some editorial control). Pat didn’t want it to become my research. My (somewhat disingenuous) response was to emphasise she had been the ‘expert’ in the data collection; now I was taking on that mantle for the analysis (Finlay and Molano-Fisher 2009).

Participant Validation?

Many qualitative researchers embrace the idea of participant validation or member checking to ‘prove’ the validity of their research. Here, researchers refer their evolving analysis back to their participants for confirmation: when the participant agrees with the researcher’s assessment, it is seen as strengthening the researcher’s argument. Time and again as you read reports you will see researchers claiming their research is trustworthy because participants have affirmed the results.

Such assurance and confidence, however, may be misplaced. It needs to be remembered that participants have their own motives, needs and interests. They also have varying degrees of insight. Moreover, what may have been true for them at the time of the interview may no longer be the case. Their ability to put themselves back into the specific research context may well be compromised. For all these reasons, processes of participant validation need to be conducted carefully and with awareness of the complex conscious, unconscious and contingent dimensions which may lead a participant to support or refute any one analysis. (Of course, the researcher, too, is subject to their own complex conscious, unconscious and contingent elements, and hence the need for researcher reflexivity.) It also comes down to the epistemological assumptions of the study and whether it can be validated in this way. Member checking might be appropriate in a post-positivist, realist study; it is less meaningful for interpretive, relativist studies where meanings are more fluid and there isn’t one ‘truth’ to affirm.

When I did my PhD research, it was suggested that I take my interview transcripts back to participants to check them and share my findings to gain their approval. In practice, both processes proved sticky and backfired. I learned an uncomfortable lesson–namely to avoid engaging procedures on autopilot.

Do participants want to see interview transcripts? After all, they’ve already given their time to the researcher. Are we requiring they spend more time reading the transcript? Also, re-visiting the interview via the transcript can be emotionally taxing. If a distressing subject was talked about, do the participants want to be reminded of it yet again? More than this, if you’ve ever seen a transcript, you’ll know words often come across as jumbled, rambling, full of ‘ums’ and ‘errs’. People often feel embarrassed when they realise how inarticulate they have been.

Of course, there are situations where a participant would value seeing the transcript. It may give them an opportunity to pick out bits they’d prefer to be removed. In one study I participated in, I asked to see the transcript, following which I requested that a passage be removed: I felt too exposed especially as the passage compromised my anonymity. The point is to offer the participant a choice.

► Example

When it comes to participants ‘validating’ analyses, further critical questions arise. If it’s an interpretive study, then who holds the authorial control? When carrying out some case study research on the lived experience of early stage multiple sclerosis (MS) (Finlay 2003), I did take my emerging analysis back to my participant, Ann, but this was more about collaborative sharing than validation (Finlay and Langdridge 2007):

As Ann was a physiotherapist, she had a reasonable understanding of the aims, process and intended outcomes of my case study research. This was important as it meant that her consent to take part in the research was properly informed…While she wanted an opportunity for discussion, she seemed content to hand authorial control to me…

Ann was particularly active on hearing my preliminary analysis of the interviews with her. She affirmed certain themes, suggesting I had captured her experience ‘nicely’. At other points she suggested my analysis (particularly my metaphorical flourishes) needed to be ‘toned down’ as she didn’t feel they adequately represented her ordinary, everyday experience. One notable example here was my initial use of an analogy: that of Ann situation being akin to ‘living with an alien monster’. I rather liked this metaphor, regarding it as both punchy and poetic, and was reluctant to let it go. However, it was not something Ann could relate to. I therefore deleted all references to the monster while retaining (I ruefully acknowledge) some sense of the notion of alien infiltration.

In retrospect, I can see that it was useful to get Ann’s feedback. For one thing, it helped me to better appreciate how Ann had, in fact, managed to reconnect with her ‘disconnected’ arm… While Ann gave me some feedback, I retained control of my analysis and writing. In the end it is I who was choosing where, when, what and how to publish the findings. And, in the end, these are my findings, my interpretations. I could have involved Ann much more collaboratively but chose not to. (pp.194–195).

Comments

It could be argued that Ann’s involvement in co-producing the findings strengthens the trustworthiness and ethical basis of this research. This is not the same as saying that Ann has validated this study thus ensuring its veracity. It’s about acknowledging that findings emerge in a specific context. Another researcher, or a study undertaken at another time, could unfold a different story.

In his critical exploration of participant validation, Ashworth (1993) supports it on political-moral grounds but warns against taking participants’ evaluations too seriously: after all, it may be in their interest to protect their ‘socially presented selves’. As he notes, “Participant validation is flawed…, since the ‘atmosphere of safety’ that would allow the individual to lower his or her defences, cease ‘presentation’, and act in open candour (if this is possible), is hardly likely to be achieved in the research encounter” (Ashworth 1993, p.15).

Researcher Self-Care

The all-consuming nature of data analysis can be stressful, overwhelming, disorientating and painful. This was shown poignantly in a study looking at therapists’ bodily engagement with research, by Bager-Charleson et al. (2018). One therapist owned: “It’s been horrific, I’ve agonised so much, feeling like a fraud, so stupid... I’ve been feeling desperate, all the time thinking that I am doing this right with themes and codes and tables” (2018, p.14).

While formal ethical guidelines tend to focus on protecting the client, the researcher also needs protecting. Doing research can be stressful and lonely. “When support is present it can make the research process more bearable, less stressful, more manageable, more interesting and even quite an exciting process” (Sreenan et al. 2015, p.249).

When we engage relationally as researchers, we can be drawn into participants’ own distress or trauma. There is an ethical imperative to be reflexive about our research processes; we need to make active use of supportive opportunities (such as continuing professional development and supervision). Without this reflexivity, we can be in danger of using the research to act out of awareness and simply reproduce prejudices and partialities, undermining the credibility of the researc. Also, as researchers we need to give ourselves time to think, build our confidence and trust our intuitions. We also need to make sure that we are kept safe as researchers. Supervision offers an opportunity to learn, be mentored and process ethical dilemmas where ‘mistakes’ can be viewed with curiosity, as a path to growth and learning (Finlay 2019).

Sometimes we need to prioritise our self-care. Indeed, this can be seen as an ethical-professional ‘duty’. The analysis phase, especially, can be a taxing time for qualitative researchers, who can feel they are ‘drowning’ in data, including participants’ emotions and vulnerability. A participant from the Bager-Charleson et al. (2018) study expressed this well: “There would be different sentences in each transcript, it was like a sword going through me, right there where my heart is, where my soul is, and then the tears would come and sometimes it’s quite unexpected” (p.14).

► Example

Through my own research on trauma, I’ve experienced first-hand the challenge of managing my own emotions to minimise the danger of secondary traumatisation. The use of supervision (and an internal supervisor) becomes important. In the following example of reflexive journaling with my internal supervisor, I show how the process enabled me to better attune to my participant’s experience while simultaneously protecting myself from getting lost in the trauma of my research topic (the experience of having a traumatic abortion–see Finlay and Payman 2013):

The interview made a profound impact on me. I had anticipated finding Eve’s experience intense and painful to hear. What I had not expected were certain disturbing images which haunt me still. Through these I caught the edge of a deep and abiding trauma. As I faced Eve in the interview and later dwelt with the data, I was aware of a continuing, lurking impulse to flee, cut off and deny… I forced myself to stay present with Eve’s story and open to our relational space…

Transcription has been hard … I’m on my third day …I keep needing to stop. I recognize my sense of feeling disturbed, a fuzzy but tight spiralling anxious grip in my stomach. I want to stop. I tune into my felt-sense:

I have that fuzzy feeling… I am finding it difficult to breathe – breathing shallowly. …There are some tears there; aloneness; an unspeakable horror. My tummy tightens some more… [and says] ‘I need to hold on; I need to hold in; I need to not cry, not speak’.

I reflect then on these words. I wonder to what extent they reflect Eve’s experience and how she had to hold on to her emotions and push down her words (Finlay 2015).

Concluding the Research and Dissemination

The end phase of research involves tying things up with participants, and then writing up and disseminating the research.

The process of tying up the research with participants usually involves some sort of debrief towards closure of the research relationship. When and how this is achieved varies enormously depending on the type of research involved. It may occur for a few minutes after the interview or survey, with researcher and participant perhaps sharing their observations and experience. In more collaborative types of research, the process is layered and ongoing. Whichever situation, participants should be offered an opportunity to reflect on their experience–and learn what will happen to their data.

Fresh ethical questions arise in the stages that follow relating to our sense of discomfort when writing up and when presenting to the wider world.

Discomfort When Writing Up

When settling down to write, researchers confront the ethical challenge of treating their participants as objects to ‘talk about’ rather than as persons to ‘talk with’. Many will experience the discomfort that goes with writing about others in an objectifying way. Josselson (1996) expresses this discomfort well as she owns some guilt and shame:

My guilt, I think, comes from my knowing that I have taken myself out of relationship with my participants (with whom, during the interview, I was in intimate relationship) to be in relationship with my readers. I have, in a sense, been talking about them behind their backs and doing so publicly...for my own purposes…I am guilty about being an intruder and… betrayer… I suspect this shame is about my exhibitionism, shame that I am using these people’s lives to exhibit myself, my analytic prowess, my cleverness. I am using them as extensions of my own narcissism and fear being caught, seen in this process. (Josselson 1996, p.70).

There are no easy ways to preclude such feelings of discomfort. However, being reflexively aware of both the nature of our research enterprise and our ethical responsibilities is a good place to start. Just as in life, we make choices in difficult, uncertain circumstances, and cope with competing demands and responsibilities.

It also helps if you believe your research has the potential to benefit, at some level, your participants even if your initial intention was to benefit a wider community. In the following extract, a co-researcher in Morrow’s study of the experience of sexual abuse (mentioned above) shares her positive response to the experience of being a co-analyst:

The participant co-researcher analytic process was a shared voice…That creates the experience of being understood. The amount of, just, honor and respect – it’s just not like anything I’ve ever experienced, Sue. The research is also…it rings true…You have done something really extraordinary. It’s so much more than a dissertation…Honor and respect. That’s what we all lost. Reading it was an experience of that. It’s touching the place I’ve been protecting, I think – the place I’m afraid to open up, even to myself. It’s the place that believes I’m honourable, worth knowing. (Morrow 2006, p.165).

Presenting to the Wider World

When researchers present their findings to wider professional and academic circles, the first ethical priority is to re-present the research honestly, accurately and with integrity. This means, for instance, not plagiarising another’s work and owning any investments and competing interests. The Committee on Publication Ethics (2019) conducted a survey and focus group of 656 editors of humanities and social science journals. They found that the two most pressing ethical problems editors face were: i. writing quality barriers and English language while remaining inclusive (64%) and ii. plagiarism and poor attribution practices (58%). Participants noted that the likelihood of self-plagiarism and predatory publishing was likely to increase given our current output-orientated academic culture.

Beyond issues around getting published, further ethical discomfort can arise when disseminating research. It’s important to factor in how others may react to experiences that participants have been willing to share. For example, in the Ellis et al. (1997) research on the experience of bulimia, the co-researchers needed to think carefully about how they would be seen by others after telling their stories–particularly as they were about to apply for academic jobs. The research article they collaboratively wrote was to become part of their job application packets and clearly identified them as women with eating disorders if not other emotional vulnerabilities (Ellis 2007).

We also carry the responsibility to respect and be sensitive to our audiences. When I’ve talked of my traumatic abortion study at conferences, I’ve been acutely aware of the need to avoid burdening the audience with excessive detail and painful imagery. Mindful that there will be people in the audience who themselves have had distressing abortion experiences, I try to offer warnings that give them some choice over whether they hear/read my work.

In my research with Ann about her experience of MS, Ann was keen for me to share her story. She wanted me to ‘spread the word’ to health care professionals about what it was ‘really like to have MS’. Over the last 15 years, I have written about and presented our research many times. I have remained mindful of the ethics of protecting Ann’s identity by changing random biographical details given the risk of her being identified by those reading the research. I have also sought to evoke and represent her experience while transparently owning my interpretive flourishes. I remain touched when I recognise how others have been impacted by hearing Ann’s poignant story. People who themselves had had their lives affected by MS seemed grateful for the way the research voiced something of their experience. But it was the wider impact on health professionals which I particularly valued. The research helped them recognise the need to tune in more to their patients’ inside experience. In this respect, I believe I have honoured Ann’s experience.

Summary

In this chapter, I’ve highlighted some of the ethical dilemmas we face when conducting research. I’ve argued for the need to be ethically sensitive and reflexive throughout the research process, handling each situation as it arises in context. I’ve also shown how care of participants and researcher self-care go hand-in-hand. The trustworthiness and integrity of the research must be balanced by our respect and concern for our participants’ well-being, ourselves and our wider communities.

As you engage in research, you’ll need to apply the code of ethics relevant to your professional situation. That said, professional ethical guidelines, while useful, can never prepare us sufficiently for situations arising in the research which make our heads spin and hearts ache (Ellis 2007; Finlay and Molano-Fisher 2009). As Reid et al. (2018) note, “Troubling dilemmas are sometimes hard to anticipate and require response in the moment”. At every stage of your study, you’ll find yourself reflexively grappling with the minutiae and conundrums that surface in all worthwhile research. The challenge is to make our ethical judgements with care, humane intention, reflexivity and as much conscientiousness as we can summon.

Ethical tensions confront researchers at each stage of research. In the pre-research phase, particular attention needs to be paid to anonymity/confidentiality and informed consent. During data collection and analysis, care of participants and researcher self-care go together, and there is a need to manage emotional intensity and power relations. In the writing up and dissemination phases research integrity and care for wider communities are prioritised. There is a need to be ethically sensitive and reflexive throughout, handling each individual situation and the complex relational dynamics involved as they arise in context. What may seem responsible, respectful and caring to one person may not to another. It depends. Negotiating an ethical path can often be tricky and compromises may need to be made. The trustworthiness and integrity of the research must be balanced by respect of, and concern for, the well-being of participants, researchers, and wider communities. The challenge is to make ethical judgements with caring, humane intention, reflexivity, and as much conscientiousness as researchers can summon.

Notes

- 1.

Legally speaking, data is only ‘anonymised’ when individuals can no longer be identified. A dataset that has identifying information removed but which is linked to a separate file (including consent forms) is not strictly anonymised (and hence it is often called ‘pseudonymised’).

References

Ashworth, P. D. (1993). Participant agreement in the justification of qualitative findings. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 24, 3–16.

Bager-Charleson, S., Du Plock, S., & McBeath, A. (2018). Therapists have a lot to add to the field of research, but many don’t make it there: A narrative thematic inquiry into counsellors’ and psychotherapists’ embodied engagement with research. Language and Psychoanalysis, 7(1), 4–22. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.7565/landp.v7i1.1580.

Bochner, A. P. (1984). The functions of communication in interpersonal bonding. In C. Arnold & J. Bowers (Eds.), The handbook of rhetoric and communication (pp. 544–621). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

British Psychological Society. (2018). Data protection regulation: Guidance for researchers. Retrieved from https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/bps.org.uk/files/Policy/Policy%20-%20Files/Data%20Protection%20Regulation%20-%20Guidance%20for%20Researchers.pdf

Committee on Publication Ethics. (2019). Exploring publication ethics in the arts, humanities, and social sciences: COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics). Initial Research Findings. Retrieved from https://publicationethics.org/files/u7140/COPE%20AHSS_Survey_Key_Findings_SCREEN_AW.pdf

Ellis, C. (2007). Telling secrets, revealing lives: Relational ethics in research with intimate others. Qualitative Inquiry, 3, 13–29.

Ellis, C., Kiesinger, C. E., & Tillmann-Healy, L. M. (1997). Interactive interviewing: Talking about emotional experience. In R. Hertz (Ed.), Reflexivity and voice (pp. 119–149). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Etherington, K. (2007). Ethical research in reflexive relationships. Qualitative Inquiry, 13(5), 599–616.

Finlay, L. (2003). The intertwining of body, self and world: A phenomenological study of living with recently diagnosed multiple sclerosis. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 34, 157–178.

Finlay, L. (2015). The experience of ‘Entrapped Grief’ following traumatic abortion. International Journal of Integrative Psychotherapy, 6, 26–53.

Finlay, L. (2019). Practical ethics in counselling and psychotherapy: A relational approach. London: Sage.

Finlay, L., & Ballinger, C. (Eds.). (2006). Qualitative research for allied health professionals: Challenging choices. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley.

Finlay, L., & Langdridge, D. (2007). Embodiment. In W. Hollway, H. Lucey, & A. Phoenix (Eds.), Social psychology matters (pp. 173–198). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Finlay, L., & Molano-Fisher, P. (2008). Transforming’ self and world: A phenomenological study of a changing lifeworld following a cochlear implant. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 11, 255–267. (Online version available from 2007.).

Finlay, L., & Molano-Fisher, P. (2009). Reflexively probing relational ethical challenges. Qualitative Methods in Psychology, 7, 30–34.

Finlay, L., & Payman, B. (2013). This rifled and bleeding womb: A reflexive-relational phenomenological case study of traumatic abortion experience. Janus Head, In E. Simms (Ed.). Special issue on ‘feminist phenomenology’, 13(1), 144–175.

Guillemin, M., & Gillam, L. (2004). Ethics, reflexivity, and ‘ethically important moments’ in research. Qualitative Inquiry, 10(2), 261–280. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800403262360.

Halling, S., Leifer, M., & Rowe, J. O. (1999). Emergence of the dialogal approach: Forgiving another. In C. T. Fischer (Ed.), Qualitative research methods for psychology: Introduction through empirical studies (pp. 247–278). San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press.

Hertz, R. (1997). Reflexivity and Voice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hunt, J. C. (1989). Psychoanalytic aspects of fieldwork (Qualitative Research Methods, 18). Newbury Park: Sage.

Josselson, R. (1996). On writing other people’s lives: Self analytic reflections of a narrative researcher. In R. Josselson (Ed.), Ethical process in the narrative study of lives (Vol. 4, pp. 60–71). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Krüger, A. (2007). An introduction to the ethics of gestalt research with informants. European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy, 2, 17–22.

Lilienfeld, S. O. (2017). Psychology’s replication crisis and the grant culture: Righting the ship. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(4), 660–664.

Madill, A. (2009). Construction of anger in one successful case of psychodynamic interpersonal psychotherapy: Problem (re)formulation and the negotiation of moral context. The European Journal for Qualitative Research in Psychotherapy, 4, 20–29. Retrieved from https://ejqrp.org/index.php/ejqrp/article/view/23/20.

Morrow, S. L. (2006). Honor and respect: Feminist collaborative research with sexually abused women. In C. T. Fischer (Ed.), Qualitative research methods for psychology: Introduction through empirical studies (pp. 143–172). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Parker, I. (1992). Discourse dynamics: Critical analysis for social and individual psychology. London: Routledge.

Proctor, G. (2002). The dynamics of power in counselling and psychotherapy: Ethics, politics and practice. Ross-on-Wye: PCCS Books.

Reid, A.-M., Brown, J. M., Smith, J. M., Cope, A. C., & Jamieson, S. (2018). Ethical dilemmas and reflexivity in qualitative research. Perspectives on Medical Education, 7(2), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0412-2.

Sreenan, B., Smith, H., & Frost, C. (2015). Student top tips. In A. Vossler & N. Moller (Eds.), The counselling and psychotherapy research handbook (pp. 245–256). Los Angeles: Sage.

Thériault, A., & Gazzola, N. (2006). What are the sources of feelings of incompetence in experienced therapists? Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 19(4), 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070601090113.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Finlay, L. (2020). Ethical Research? Examining Knotty, Moment-to-Moment Challenges Throughout the Research Process. In: Bager-Charleson, S., McBeath, A. (eds) Enjoying Research in Counselling and Psychotherapy. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55127-8_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-55127-8_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-55126-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-55127-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)