Abstract

In this book, we ask readers to consider what value means in CSR (for business and society, both by drawing from the past and by looking into the future), where it comes from and how it is enacted (organizational legacies or managers’ values) and its purpose (communicative value, co-operation, community). The chapter introduces the idea of value from an economic perspective and then explores the integration of values at the core of ethical business practice and CSR activities. It also provides an overview of the chapters, including historical developments of value in CSR, how value is linked to a positive vision of the future and how it is communicated by a range of private and public organizations to various audiences. Finally, it explains how leaders’ values can drive responsible business practice and enhance social cohesion, solidarity and resilience in fractured and unequal communities.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Economic value

- Shared value

- Managers’ values

- Corporate responsibility

- The UN Sustainable Development Goals

We live in a world of competing and sometimes, it seems, increasingly antagonistic values. These values are shaped by a bewildering multitude of experiences, as well as diverse political, religious, ethical and cultural assumptions of how to behave, how to treat others and how we understand what is ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ at the most fundamental level. So, what if anything could we hold on to as common values that might underpin corporate social responsibility (CSR) in an international context? The United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 reflect a worldwide common agenda for sustainable development, built around the painstakingly negotiated shared values of the UN Charter and subsequent efforts to build a peaceful world of mutually respectful coexistence and justice. Each of the UN’s ambitious 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) includes a range of governmental, corporate and personal responsibilities as citizens and specifies a framework for collective action through a Global Partnership. The role of business and the private sector in this partnership is essential, but cannot be untangled or divorced from the actions of political leaders and bodies, the UN system and other international institutions, civil society, indigenous peoples, the scientific and academic community—‘and all people’ (UN 2015). It is in this spirit that we explore the importance of values in CSR.

In this book, we capture and explore different aspects of value in corporate social responsibility (CSR). This includes the historical development of value in CSR, how value is linked to a positive vision of the future and how it is communicated by a range of private and public organizations to various audiences. The book also contrasts corporate strategic value with cooperative value, and community value. Finally, it explains how leaders’ values can drive responsible business practice and enhance social cohesion, solidarity and resilience in fractured and unequal communities. The book therefore asks the reader to consider what value means in CSR (for business and society, both by drawing from the past and by looking into the future), where it comes from and how it is enacted (organizational legacies or managers’ values) and its purpose (communicative value, co-operation, community). The book also presents CSR as a global project by noting how values are cultural. Understanding value creation or co-creation, value delivery and value measurement in corporate responsibility, and connecting these with corporate and societal values, offers a chance to re-legitimize businesses in their attempts to meet sustainability goals, including those ambitious targets mapped out by the UN.

1.1 Defining Value: An Economic Perspective

Defining value in a way that prioritizes sustainability is both a business opportunity and a challenge. Markets aim to create all sorts of value: economic value, social value, brand value, lifetime value and so on. Some values sit uneasily alongside others.

From the economic reductionism perspective, value might be reduced to cost-benefit calculations (from the era of Fordism) where this means ‘value for money’ and the emphasis is on ‘more of something for less money’ (or less labour). In business studies, especially in marketing, the concept of value is most commonly understood as a subjective measure of the perceived utility of a product or service (Grönroos and Ravald 2011). The economic value offered by firms to society is just one kind of value. Most obviously, value has a more everyday meaning relating to our beliefs about right and wrong, or as it relates to ethics. One of the Oxford Dictionaries’ definitions presents value as ‘principles or standards of behaviour; one’s judgement of what is important in life’. We see a return to this definition in the consumer as citizen and in CSR. The legitimacy of economic value is that this was what ‘the free market’ promises to consumers and ironically economic value may be easier to justify morally than the market’s expansion into, or claims around, other value domains.

In terms of who creates (economic) value, the cost-benefit approach invites the view that value is created by an organization, at first through production, and later through marketing and/or branding, that is, brand valueor the recognition that value is not (just) in production, but in the symbolic meanings of brands. This is an ‘internal’ perspective of value that suggests it is created inside the organization by the actors who assemble it. However, this view has been challenged by the idea of a ‘value system’ and more recently by the idea of ‘value in use’ and ‘shared value’.

For example, Porter’s (1985) value systemtheorization recognizes that value is incrementally created through material and immaterial changes. This may be ‘internal’, capturing the different functions of an organization, but it also recognizes external actors or stakeholders. For example, as aluminium is extracted from the ground, then transformed into a statement of design and lifestyle ‘cool’ in the form of an iPhone. In other words, the Porter’s approach adopts a macro (i.e., business system) level of analysis of value, as it shows all the activities or operations necessary to transform raw materials into goods/services that are consumed by people. The ‘value system’ allows an examination of where value is added, where more can be added (or costs reduced) and what sorts of value may be added, and some see it as an important planning tool to meet ‘sustainable competitive advantage’ (Priem et al. 1997).

Such macro arrangements also have ramifications for marketing practices where consumers are seen as a primary source of value. The turn to the consumer is best captured in ‘relationship marketing’ where marketers nurture, expand and exploit what they know about consumers and aim to extract value from ‘long-term mutually beneficial relationships’. Alternatively, it can be found in the idea of ‘customer lifetime value’—a prediction of the net profit attributed to entire future relationships with customers—that recognizes consumers as more valuable than transactions. In recent years, especially in marketing, another target for value has been consumer data. Data is seen as value in itself and is inherently valued by business (e.g., consumer databases or insight, value exchange, integrated campaigns), but raises significant privacy issues about how and whether businesses respect consumers/individuals’ boundaries (see, e.g., Shoshana Zuboff’s 2019, Surveillance Capitalism, a chilling presentation of business models and algorithms underpinning the digital economies). In parallel to ‘escalating market value and values’, consumers and other stakeholders ‘learn’ to be savvy. They seek new values from their engagement with markets and these might be financial, but also result in other demands, that is, ethical business practice.

1.2 Ethical Business Practice, CSR and Value(s)

As ideas about value expand in business contexts, we are naturally drawn back to broader definitions of values. For example, several authors note that Western economies keep perpetuating several values such as individualism, with implications for care and responsibility (Bauman 2013), materialism, with a contested debate about implications for human relationships (Fromm 1976; Illouz 2007; Miller 2008; Molesworth and Grigore 2019) or competitiveness, with implications for identity (Marcuse 1964). The task of businesses might seem to be to persistently create new value, which risks a sort of imperialism where markets seek to capture more and more ‘values’ in their quest for new value with the implication that all aspects of life become marketized. Similar ideas are captured in Klein’s (2009) ‘No Logo’, Barber’s (2008) ‘Consumed: How markets corrupt children, infantilize adults, and swallow citizens whole’, Kuttner’s (1999) ‘Everything for Sale: The virtues and limits of markets’ or Sandel’s (2012) ‘What money can’t buy: the moral limits of markets’ where the authors draw attention to the fact that markets erode moral values. Indeed, in an experiment about how people behave when they received financial incentives in a simulated marketplace conducted by researchers at the Universities of Bonn and Bamberg the main result was that: ‘people decide very differently depending on whether they act in markets or outside of markets […] individually, outside of markets, people have difficulties in killing these mice, they don’t want the money. In markets most people actually find it easier to kill the mice even for very small amounts of money’ (DW 2013).

Although business might be about the generation of value, ethical issues in business are therefore also tied to the moral values held by individuals and the contexts in which they are situated (Forsyth 1992). This brings us to an alternative way of seeing value: ‘shared value’. Porter and Kramer (2019) suggest that the purpose of organizations needs to be redefined so that there is a focus not just on profit and value for money, but on creating shared value, such that economic value can also create value for society. This view brings together a company’s success and social progress, opening the possibility of new discourses around new sources of value that can be obtained by connecting business and society. In other words, organizations need to create economic value in a way that also creates value for society. The shared value perspective places CSR at the hearth of business, and Porter and Kramer (2019) see this as ‘our best chance to legitimize business again’.

The origins of CSR can be tracked to at least the nineteenth century (religiously motivated) and in a more secular form from the 1920s when Clark mentions that businesses have obligations to society. A decade later, Berle (1932: 1365) suggests that managers have to provide ‘safety, security, or means of support for that part of the community which is unable to earn its living in the normal channels of work or trade’. One of the most referenced early definition of CSR is Bowen’s (1953: 6) one, who states that it encompasses ‘the obligations of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of actions which are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of our society’. From these early conceptualizations, we note that there was a search for a deeper purpose of firms in society that extends beyond just making money or achieving financial value, to accomplishing contributions to or ‘value’ for the community and society.

CSR takes place within specific cultural contexts and therefore produces local or regional types of CSR theories/philosophy and practices. CSR has been developed in Western developed countries and is therefore underpinned by free market logic, conditions and values, but varies significantly in each country (Dahlsrud 2008; Gjølberg 2009; Jamali et al. 2017). Dahlsrud (2008) and Gjølberg (2009), for example, argue that CSR ‘cannot be separated from the contextual factors of the nation in which it is practiced’.

As such, studies on ‘CSR and values’ attempt to understand the context, or culture, or ‘local’ philosophy to identify nuances in various CSR theories and practices. Culture is learned within a society and therefore shapes collective or individual values. Organizations operate in national or regional relations that create a distinctive environment for their practice; hence CSR is also dependent on the contexts or institutional dynamics in which it is assembled. For example, Wang and Juslin (2009) show how CSR can be interpreted through a moral philosophy—Confucianism—that reveals the ethical values in CSR work in Chinese culture. In their paper, the authors focus on a ‘harmony approach’ which draws on Confucian values to show how people can be motivated to assume individual responsibilities which in turn can lead to self-cultivation, self-control and a harmonious society (Wang and Juslin 2009). In such context, the motivation for conducting CSR becomes a cultivation of virtues, where people learn to live in harmony with nature, and hence they are able to assemble a ‘harmonious society’. Other studies that focus on developing countries show how CSR has been introduced by multinationals, aiming to introduce a set of values that does not account for specific practices and contexts, which results in a gap between the public discourse of CSR and the actual practice (Jamali et al. 2017), that is, a ‘selective decoupling’, where rather than transform an institution or a context, CSR remains a decoupled practice separate from the realities or conditions on the ground. Jamali et al. (2017) question whether CSR can actually improve the lives of beneficiaries they claim to help or the communities especially where such CSR practices remain divorced from the conditions in which they take place.

1.3 The Role of Value(s) in Corporate Responsibility Theories and Practices

In this book, we look at concepts and practices that might better explain and align both the ‘value’ and ‘values’ of corporate responsibility and offer solutions to individuals engaged in making corporate responsibility a reality, rather than a discredited marketing exercise. The edited collection brings together papers presented at the 7th International Conference on Social Responsibility Ethics and Sustainable Business, held at Norwegian Business School in Oslo on the 12th and 13th of October 2018. This conference invited submissions that explore the intersections between and ramifications of ‘value(s)’ and ‘corporate social responsibility’. In this book we therefore (re)connect value(s) and corporate social responsibility. We present articles that include current thinking and developments by both academics and practitioners, combine theoretical foundations on value and CSR with practical insights and help managers in decision-making processes. Additionally, we present conceptualizations from various cultures including Japan, Tanzania, Bangladesh, United Kingdom, Norway, France, Germany, Belgium and Romania.

The first part of the book adopts a theoretical approach on value and values, and their role in shaping CSR frameworks, tools, conceptualizations, and then how practice is informed by such theories. For example, in Chap. 2, Candice Chow and Nada Kakabadse talk about the importance of executives’ values in shaping enterprises’ corporate responsibility practices. Making use of a ‘values-theory’ lens and drawing on stories from Canadian executives, this chapter shows how executives’ values have come to the fore and shaped their views concerning corporate responsibility practice. Additionally, these stories highlight the link between executives’ values and corporate responsibility adoption, that is, the more robust the values, the stronger the individual’s belief in their ability to drive change without influence from external constraints. This chapter concludes by advocating for the need to emphazise and integrate management values into all levels of further and higher education. Personalreflexivity and immersiveexperiential learning should be championed to help strengthen and raise awareness of individuals’ values and to acknowledge that the personal growth process is an essential driver for positive change.

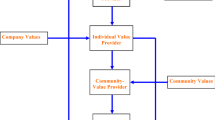

Moving from the importance of executives’ values in shaping organizational practices, then in Chap. 3, Atle Andreassen Raa problematizes philanthropy from the perspective of economic theory. The author concludes by relating the stakeholder-shareholder dichotomy in CSR discourses with a corresponding dichotomy in the interpretation of Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ with or without morality and ethics included. In this way, Chap. 3 deepens our understanding of how philanthropy and CSR can be reconciled from an economic and ethical perspective. Then, in Chap. 4, Dušan Kučera situates the desirable and declared value concept of CSR (corporate social responsibility) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with the present regression of moral values in Western society and Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). The author argues that from a philosophical perspective, the ‘crisis of values’ and the ‘moral recession’ of the Western societies are caused by a modern dualist conception of corporate goals. In Chap. 5, Gerhard Kosinowski introduces a strategic tool to create ‘cooperative value’. His theoretical approach shows how and why cooperative banks’ activities exceed the creation of value for their members. Drawing on 24 in-depth interviews with practitioners from German cooperative banks, the author reveals that they have the aspiration to be a high-quality, long-term partner for all their clients and, as such, they act as orchestrators for their members and non-member clients.

The second part of the book provides case studies, or ‘local’ interpretations of, or empirical studies on how, by corporate responsibility into organizational strategies and practices, value for all stakeholders can be generated, which in turn may cultivate values. For example, in Chap. 6, David McQueen and Amelia Turner present a case study exploring the environmental and sustainable values of UK energy firm Ecotricityand its founding-director and owner, Dale Vince. The authors consider Ecotricity’s expansion and diversification from a clean energy provider to offering a range of sustainable business initiatives including electric car charging stations, grid-scale battery storage, green mobile phone service and vegan school food supplies. It also explores marketing strategies and media coverage of the company and assesses the extent to which the director’s single-minded and uncompromising values have helped secure a loyal, niche customer base and could provide a model for future business success in the face of the rapidly accelerating climate crisis. The chapter concludes with a critical discussion of CSR in light of this crisis and the need for sustainability to take centre stage at every level of business decision-making and strategic planning.

From a case study exploring the environmental and sustainable values of UK energy firm, we then move to Chap. 7, where Adrian Baumgartner proposes the concept of strategic corporate social responsibility (SCSR), defined as a corporation’s clearly articulated and communicated policies and practices towards gaining a competitive advantage by addressing unmet social needs. His study shows that SCSR activities have a positive impact not only on corporate financial performance (CFP), or economic value (EV) but also on societal value (SV). The proposed framework aims to support future research on CSR and related concepts, as well as to provide practical guidance and recommendations to business leaders aiming to implement the principles of CSR in their business. In Chap. 8, Florian Weber and Kerstin Fehre examine how corporate social responsibility activity (CSRA) and corporate social responsibility communication (CSRC) impact legitimacy. The empirical results indicate that neither CSRA, nor CSRC have a standalone effect; nonetheless, CSR is important for organizational legitimacy. The authors suggest that a CSR strategy that combines high levels of CSRA with low levels of CSRC is the most effective way for (re)gaining legitimacy, while an opposite strategy that combines low levels of CSRA with high levels of CSRC emerges is the worst. In another empirical study, Anca-Teodora Şerban-Oprescu provides an analysis of the impact of cultural and educational values on the entrepreneurial mindset. Chapter 9 therefore focuses on three main aspects: the connection between education and entrepreneurship; the risk aversion in entrepreneurship, and related ethics, social responsibility and entrepreneurship. The author concludes that Romanians still need to have a more profound understanding of the core values that make for ethical and socially responsible behaviour in independent ventures.

In Chap. 10, Mohammad Tazul Islam and Katsuhiko Kokubu interrogate the use of legitimacy theory to infer managers’ perceptions of corporate social reporting in a bank from a developing country, Bangladesh. Their study finds that CSR as a concept is not clear to practitioners and regulators, who mostly view it as corporate philanthropic activity. Moreover, the authors find that there is no structured format for CSR reporting; instead the reporting format is bank-centric. From a legitimacy theory perspective, the study therefore confirms that the legitimate reasons for CSR reporting in the banking industry of Bangladesh are mostly driven by external stakeholder influences (i.e., regulators, employees, local community, NGOs, political leader and civil society). In Chap. 11, Omary Swallehe evaluates activities of the corporate citizens in Tanzania to find the best way of aligning CSR initiatives to obtain mutual benefits for both the organizations and the general public. Drawing on a survey of both public and private organizations, the authors find that the majority of the organizations regard CSR as a source of competitive advantage through legitimization of companies’ offerings to the customers and general public. When CSR is not seen to provide competitive advantage opportunities, then the organizations are unlikely to justify the ‘value’ of CSR for their organization.

1.4 Value(s) and Corporate Responsibility: Quo Vadis?

The complex and diverse ‘context and culture’ for understanding CSR and values touched on above changed worldwide in 2020. This was because, as we have all discovered, Covid-19 changed everything. It has been said that our lives will never be the same, but exactly how is hard to say as this book goes to press. Optimists believe that this pandemic will make us more compassionate and empathetic, others perhaps cling to the hope that everything will be as it was before. Pessimists think that these are the last days of humanity, or that at the very least we are on the brink of an economic downturn that will rival the Great Depression of the 1930s. As editors, we were caught in the midst of the pandemic in February and March 2020 and, we discussed by video conference from our homes, rather than our usual workplaces, the impact that this dramatic global lockdown could have on corporate responsibility and values while finalizing this book. Notions of values and responsibility have already changed, that is for sure. Many companies are suffering enormous losses, or bankruptcy, while others struggle on and show their solidarity and responsibility to customers, their staff and the wider community in empathetic and creative ways. Not all companies are making losses: Amazon, for instance, is making gains. However, not everything is about financial gains, as we are learning. We have lost our freedoms and we are locked in our homes. Keeping your distance is now, paradoxically, a sign that you love someone, better still, that you love and care for everyone, even people you have never met and never will. The need for empathy and care are at the heart of the final chapter of the book by David McQueen, Francisca Farache and Georgiana Grigore which explores how Nietzsche’s troubling notions of the ‘herd’, ‘masculine’, warrior values and attitudes to empathy for the weakest members of society have been shown to resonate in disturbing ways in the response of several right-wing populist leaders to the Coronavirus pandemic sweeping the globe in 2020. What seemed, at worse, shocking unpreparedness and a casual disregard for the well-being of vulnerable groups, or the wider safety of the nation, indicated a lack of responsibility that was thrown into dramatic relief by the quick, decisive action of other leaders, organizations and businesses.

So, this book ends with initial reflections on what extent such a worldwide health crisis is shaping our understanding of both economic value and values? There are many more issues we have not touched on. What kind of responsibilities will companies undertake, and what will be the external stakeholders’ expectations during such ‘unprecedented’ times? How will this pandemic shape our future? And how will companies demonstrate their responsibility and values to society? There are questions for future research. In this book, we join contemporary conversations on the intricate relationship between values and corporate responsibility, and we hope that it can be used for future theorizations on CSR and values, or applications within different national or organizational contexts.

References

Barber, B. R. (2008). Consumed: How markets corrupt children, infantilize adults, and swallow citizens whole. WW Norton & Company.

Bauman, Z. (2013). The Individualized Society. London: John Wiley & Sons.

Berle, A. A. Jr. (1932). ‘For Whom Corporate Managers Are Trustees: A Note’, Harvard Law Review, 45(8), 1365–1372.

Bowen, H. R. (1953). Social responsibilities of the businessman. University of Iowa Press.

Dahlsrud, A. (2008). ‘How Corporate Social Responsibility Is Defined: An Analysis of 37 Definitions’, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1–13.

DW. (2013). ‘Markets erode moral values, researchers find’, DW, Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/markets-erode-moral-values-researchers-find/a-16813795

Forsyth, D. R. (1992). ‘Judging the morality of business practices: The influence of personal moral philosophies’, Journal of business Ethics, 11(5–6), 461–470.

Fromm, E. (1976). To Have or to Be? London: Abacus.

Gjølberg, M. (2009). ‘The Origin of Corporate Social Responsibility: Global Forces or National Legacies?’, Socio-Economic Review, 7(4), 605–637.

Grönroos, C., & Ravald, A. (2011). ‘Service as business logic: implications for value creation and marketing’, Journal of Service Management, 22(1), 5–22.

Illouz E (2007). Cold intimacies: The making of emotional capitalism. Polity: Cambridge.

Jamali, D., Lund-Thomsen, P., & Khara, N. (2017). ‘CSR institutionalized myths in developing countries: An imminent threat of selective decoupling’. Business & Society, 56(3), 454–486.

Kuttner, R. (1999). Everything for sale: The virtues and limits of markets. University of Chicago Press.

Klein, N. (2009). No logo. Vintage Books Canada.

Marcuse, H. (1964). One-dimensional man: the ideology of advanced industrial society. Croydon: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Miller, D. (2008). The comfort of things. Polity.

Molesworth, M., & Grigore, G. (2019). Scripts people live in the marketplace: An application of Script Analysis to Confessions of a Shopaholic. Marketing Theory, 19(4), 467–488.

Porter, M. E. (1985). Value chain. The Value Chain and Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance. NY: Free Press.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2019). ‘Creating shared value’, In Managing sustainable business (pp. 323–346). Springer, Dordrecht.

Priem, R. L., Rasheed, A. M., & Amirani, S. (1997). ‘Alderson’s transvection and Porter’s value system: a comparison of two independently developed theories’, Journal of Management History, 3(2), 145–165.

Sandel, M. J. (2012). What money can’t buy: the moral limits of markets. Macmillan.

UN. (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The United Nations. Accessed at: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

Wang, L., & Juslin, H. (2009). ‘The impact of Chinese culture on corporate social responsibility: The harmony approach’, Journal of Business Ethics, 88(3), 433–451.

Zuboff, S. (2019). Surveillance capitalism and the challenge of collective action. Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Grigore, G., Stancu, A., Farache, F., McQueen, D. (2020). Corporate Responsibility and the Value of Value(s). In: Farache, F., Grigore, G., Stancu, A., McQueen, D. (eds) Values and Corporate Responsibility. Palgrave Studies in Governance, Leadership and Responsibility. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52466-1_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52466-1_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-52465-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-52466-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)