Abstract

This chapter draws on the first-named author’s doctoral research with a group of female undergraduate students at Dhofar University in Oman, a Muslim Sultanate in the Middle East. The data corpus included responses to a questionnaire, semi-structured interviews with the students, the first-named author’s critically framed observations of the context in her role as the students’ English language teacher and her analysis of the late Sultan’s royal decrees that framed and implemented Omani government policies. The second-named author contributed the chapter’s conceptual framework, which was centred on critical interculturality (Dervin, Interculturality in education: A theoretical and methodological toolkit. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Pivot/Palgrave Macmillan, 2016; Critical interculturality: Lectures and notes. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017) as a vehicle for generating new and potentially transformative approaches to researching within the educational margins. These approaches centre on ethical and rigorous contestations of cultural essentialism and hegemony, and on resisting strategies of exclusion and othering.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Although women constitute half the human population , their circumstances and conditions vary considerably across place and time, ranging from figures of influence and power to victims of systematic abuse and marginalisation. From this perspective, women as learners within the educational margins (see e.g. Aikman & Robinson-Pant, 2019; Jackson, 2004; Lee & Kim, 2018) resist categorical homogenisation and conceptual essentialism, exhibiting instead contextualised heterogeneity and situated diversity of aspirations and achievements.

This chapter explores one specific manifestation of women’s experiences as situatedly marginalised learners in a particular place and time: a group of female undergraduate students at Dhofar University in Oman, a Muslim Sultanate in the Middle East, who were the participants in the first-named author’s doctoral study (see also Burns, Coombes, Danaher, & Midgley, 2014). The focus here is on demonstrating how the concept of critical interculturality (Dervin, 2016, 2017) was effective in analysing the participants’ voices, thereby illuminating wider issues pertaining to education research, marginalisation and vocality.

The chapter consists of the following four sections:

-

The Omani background and context

-

The first-named author’s doctoral study

-

The chapter’s conceptual framework

-

Selected data analysis.

The Omani Background and Context

Oman is a country located in the Middle East, at the mouth of the Persian Gulf and with its coastline facing the Arabian Sea, and sharing land borders with the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and Yemen. Prior to 1970, Oman was a closed Muslim Sultanate (Petersen, 2016). It was not possible for tourists to enter, or for nationals to leave and expect to be able to return. Money from oil was beginning to flow, but there was no evidence of this being used to improve the infrastructure of the country or the lives of its people. There were seven kilometres of roads throughout the country, three schools for boys for basic and Koranic studies in mosques and no government hospitals. It was a divided, tribal nation, with the southernmost region, Dhofar, involved in conflict as communists from Yemen were fighting for control.

To see Oman today, a modern, technologically advanced society, one marvels at the progress made in 50 years. The country now has 32 colleges and universities, 59 hospitals and 897 medical centres, and a comprehensive road system that connects all major areas of the nation. The force behind this development was the recently deceased ruler, Sultan Qaboos bin Said. As well as bringing the country into the twenty-first century, he united what was once “Muscat and the Sultanate of Oman” into a population unified behind the name “the Sultanate of Oman”.

However, Oman remains a patriarchal, Islamic culture with distinctive gender roles. In addition, Omani traditions are valued and passed down through the generations. This confluence of tradition and tribalism on the one hand and the influence of globalisation and modernity on the other hand created a particular context in which the study reported here was conducted.

The First-Named Author’s Doctoral Study

The Participants

The participants in the study were the first generation in their families to attend university. In a male-dominant society, this opportunity afforded the women alternatives to the traditional life patterns of remaining at home to care for the children and the household. As such, these individuals were sailing in uncharted territory as they sought a path between strong cultural traditions and modern educational ways of being.

Although all the participants were from Dhofar, Arabic was a second language to some of these women, and it was not until they entered school that they began to use Arabic. In some of these cases, their mother tongue was Mahri, Jabbali or Shahri that has no written language, so the concept of reading was introduced at school. In fact, English was a third or fourth language for some participants.

All the women were between 20 and 35 years of age. Some were already mothers; some were single. Some came from the mountains, and some from the city or the plains, yet all had a common culture, a love of Islam and a respect for their traditions .

Data Collection

Samantha began collecting data with a questionnaire sent to over 100 former and current female students at the university. From the responses, she chose seven women who demonstrated a command of English that would enable her to converse with them, and who had replied with added comments showing an interest in and opinions about the questions provided. It was important that Samantha did not use a translator, as this might have restricted the perspectives that the women were willing to share. Samantha understood the privileged position that she held whereby she was trusted and the women felt safe to speak freely.

After gaining formal ethics approval from the university to carry out the research, Samantha explained the study to the participants, assuring them of anonymity and confidentiality and receiving their signed acceptance to participate. The next step was to set up semi-structured interviews with the participants. These were recorded and transcribed for analysis.

More broadly, the data corpus for the study included the responses to the questionnaire, Samantha’s semi-structured interviews with the seven students, her critically informed observations of the context in her role as the students’ English language teacher and her analysis of the late Sultan’s royal decrees that framed and implemented Omani government policies.

Data Analysis

Samantha’s analysis of the identified elements of this data corpus was animated by the application of her three research questions:

-

1.

To what extent and how had being a university student changed these women’s reported perceptions of themselves?

-

2.

In what ways did these women state that university education had affected their role/status in their families? Which factors did these women identify as enabling these changes?

-

3.

To what extent, if any, did these women perceive university education as affecting their lives in the broader contexts of the community and the nation?

Analysis of the data corpus to address these research questions was undertaken by means of applying the principles and procedures of interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) (Smith, Flowers, & Larkin, 2009; Smith & Osborn, 2003). This approach explores the participants’ lived experiences as well as their perceptions. This is achieved using idiographic and inductive techniques to offer insights into how the participants make sense of what they are experiencing (Finlay, 2009). In this study, the application of IPA included the intensive and repeated re-reading of interview transcripts; description of the context of the interview exchange; linguistic comment on how content and meaning were presented; conceptual comment relating to general interaction; the development of emergent themes; and searching for connections across these themes and then looking for patterns among the data. This rigorous process facilitated the generation and verification of understandings of the participants’ insights into their individual lives against the backdrop of the cultural, economic and political shifts in their country, their region and their world.

The Chapter’s Conceptual Framework

The second-named author contributed the chapter’s conceptual framework, which was focused on critical interculturality (Dervin, 2016, 2017) as a vehicle for generating new and potentially transformative approaches to researching within the educational borders, and also for enhancing strategies for communicating and articulating diverse voices.

With characteristic insight mixed with humour, Dervin (2017) likened “the Sampo, … [an] element of Finnish mythology” (p. 1; italics in original), to “the ‘intercultural’, [which] is often of indeterminate type [and] which we hope can bring good fortune, especially in the fields of education and communication” (p. 1). Against that backdrop, he defined critical interculturality:

… as a never-ending process of ideological struggle against solid identities, unfair power differentials, discrimination and hurtful (and often disguised) discourses of (banal) nationalism, ethnocentrism, racism and other forms of -ism. Critical interculturality is also about the now and then of interaction, beyond generalizations of contexts and interlocutors. (p. 1; italics in original)

At the same time, it is vital to note Dervin’s ambivalence about the notion of interculturality, derived partly from his extended experience of its conceptual complexity and its difficulty in being empirically observed and analysed. Again somewhat tongue-in-cheek, Dervin (2016) asserted that “I am not sure what interculturality means and refers to today, or whom it includes and excludes” (Chap. 1). Crucially, Dervin (2016) contended that “it is we who decide what is intercultural and what is not” (Chap. 1)—an invitation that we take up in the following section of this chapter. Similarly, Dervin (2016) argued that:

Culture and the concepts to follow do not exist as such. They have no agency; they are not palpable. One cannot meet a culture but people who (are made to) represent it—or rather represent imaginaries and representations of it. (Chap. 2)

More broadly, Dervin’s seminal work in this scholarly field demonstrates at once the breadth and the depth of critical interculturality and its significant synergies with multiple manifestations of researching within the educational margins. These synergies traverse theoretical and practical concerns with culture, identity, globalisation, the other and othering, human rights, intercultural competences and social (in)justice (Dervin, 2016).

From this perspective, culture and interculturality emerge as “messy” and “slippery” concepts that elude easy definition and straightforward analysis—as Dervin (2016) noted, “interculturality tends to be polysemic, fictional, and empty at the same time, conveniently meaning either too much or too little” (Chap. 1). On the other hand, culture and intercultural interactions undoubtedly generate profound effects on multiple individuals and communities as they are mobilised by different interest groups for varied purposes. In particular, as we elaborate below, we see critical interculturality as affording important insights into the possibilities for ethical and rigorous contestations of cultural essentialism and hegemony, and for strategies of resisting and subverting exclusion and othering.

Selected Data Analysis

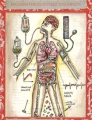

The analysis of selected data from the first-named author’s doctoral study presented in this section of the chapter needs to be understood by reference to the analytical framework that she developed for the study, presented in Fig. 12.1.

As is noted in Fig. 12.1, this analytical framework synthesised Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological human development model and Greenfield’s (2009) sociodemographic prototypes. While the comprehensive details of this framework cannot be elucidated here, the broader data analysis on which this section of the chapter draws identified several paired ideas that, rather than functioning as fixed essences or unchanging binaries, highlighted movement back and forth and dynamic tensions as evidenced in the participants’ voices. These paired ideas included:

-

community—society

-

family —individual

-

historical change—intergenerational change

-

patriarchy—equality

-

tradition —modernity

-

tribalism—nationalism

with changes and constants in the participants’ separate and shared ecologies emphasising the fluidity that was strikingly evident in their identity work.

These paired ideas, and the associated dynamic tensions for the participants and their families, were encapsulated in the late Sultan’s introduction of Omani Women’s National Day in 2007 to promote national goals for promoting women, by ensuring gender equality in law, and by educating the Omani public about the value and importance of women in nation building. Shehadeh (2010) provided examples of Omani women in various positions of responsibility, and discussed the multiple roles that such women play as “wives, mothers, employees and social changers” (n.p.) (see also Al Hasani, 2015). Shehadeh noted as well that Omani women would not have had these opportunities without support from the authorities, and he quoted Article 12 of the Basic Law of the State: “justice, equality and equal opportunities between Omanis are pillars of the Society and are guaranteed by the State” (Sultan Qaboos, 1996).

One example of the dynamic tensions accompanying the participants’ identity work against the broader backdrop of these nationwide changes related to contradictory expectations of young women being the first members of their families to enter Dhofar University. On the one hand, this access to university education accorded with the nation building that occurred after 1970, and with the official discourse of the promotion of women’s equality noted above. On the other hand, female students who showed their uncovered faces to young men from their villages brought shame to their families and distress to the students, as well as a father’s disapproval of his daughter’s confidence in presenting in front of a mixed gender class, rather than protecting her modesty. Data from the students showed their grandmothers’, and at times their mothers’, concerns that their daughters’ marriages might be under threat should they continue with their studies.

More specifically, each participant provided insights into the different opinions of family members with regard to her attending university in Dhofar. The majority of participants reported that their fathers and grandfathers, despite initial reservations in some cases, were proud of the role that they were playing in the development of the country, as well as within the family in relation to improving opportunities for the children:

My father say[s], “Take your time. If you have any project, if you have anything, if you cannot do this work, I will help you. If you don’t have time, I will give you anything that—maybe you are busy, I will do something. I will do another work that you have it to do this [important work] also.” (Participant 1)

By contrast, the participants’ mothers and grandmothers were often concerned about how the multiple roles operating in the domestic environment would be carried out: “My mother says, ‘Just—you have to do this work. If you finish, I want you to do another work’” (Participant 1).

A second dynamic tension was evidenced when participants expressed their awareness of both the scale and the significance of the changes to Omani women’s roles that the late Sultan was advocating. In doing so, they articulated support for as well as resistance to these changes within their own families. Participant 3 synthesised these divergent perspectives both powerfully and poignantly, as follows:

[The] Sultan, he want[s] to improve the country. … Women in Oman before cannot have any experience. Just they do something without understanding that [they] have [received] from their mother or their father or their grandmother, yes. But now they study to do something, to take something—they change. Mother[s] all must—women in Oman, like mother[s], can … change the life. Yes, women in Oman also can, yes, can be a mother of [Oman], to be changed.

Similarly, Participant 4 linked these profound sociocultural shifts in Oman with the material question of the different ages at which women in different generations of her family had become married. Her grandmother was “Seven … years old” when she married; her mother married at the age of “14”; and she was “20” when she married. She likened these demographic changes to a “Step by step” process of modernisation, and she extrapolated that her daughters might be “25 and 26, [something] like that” when they married.

A third example of the dynamic tensions attending the participants’ identity work was concerned with the responsibility for both work and family care falling on the woman’s shoulders. Husbands, mothers, grandmothers and the participants themselves saw this dual role of earning an income and taking care of the household and children as the woman’s domain. According to Participant 5:

Because that’s in our culture, that women should just stay at home and just take care of children, and the men should work and they would take care of the family, and they would earn money to feed their families.

Participant 5 distilled the following rationale for current changes to these traditionally gendered roles: “Because of [national] development first, and because His Majesty [has] made opportunit[ies] for women to work, and he say[s], ‘Make people [be able to access] more education [so] that women should work and they should go to schools’”. Participant 7 echoed this identification of Sultan Qaboos’s foundational national leadership in relation to the education of Omani women:

He said one word; he said at the beginning where people cannot accept the education and people who—at that time, it was so dark here. So he said, “We will learn; even under the tree, we will learn.” He opened the schools; the schools [were initially] for boys only—the rich boys also. He opened schools. He loved everything. So, because of that, we love him. He change[d] our life for the best. Also the families they change[d].

At the same time, Participant 5 communicated her understanding that the traditionally gendered roles were likely to persist in the home, thereby placing greater responsibility on Omani women:

If she can manage her time, … the effect will not be negative; it will be positive. If she can manage her time for [her] family and for her job, and balance between her family and [her] job, that will be fine. I think so.

For Participant 2, someone who was able to attain this balance “is [a] good woman and she is clever”:

I think … I will do like my mother—she take[s] care about us, and she work[s] at the same time. So I will divide my time—time for my children, and time for my job. So my job, I do that in my [workplace], and in my house. I am just a woman like any woman Omani. She has children to care about.

In a series of observations, Participant 6 explored significant differences between her friends’ and her experiences in Salalah, the capital city in Dhofar, and those of their counterparts in Muscat, the national capital. These differences accentuated striking divergences within Omani society, and constituted a timely reminder that Oman is far from being a monoculture, and that the participants’ experiences of changes centred on their English language undergraduate courses were heterogeneous and evoked complex and sometimes contradictory responses on their part and on the parts of their family members.

Participant 6 began this set of reflections by observing the noteworthy change that now her family members “ask me if they [want me] to give them some advice”. Previously, “they [didn’t] trust my opinion that much [because] our society is not that open-minded”. “[Now] they trust me [a lot], because they know that I [spend time] here [at the university] … sometimes eight or nine hours [each day]. … Before they … didn’t leave me to … spend all my time alone. But now, of course.”

In addition to enhanced trust by her family members, Participant 6 identified other changes in how those family members perceived her now: “… they look at me as [being a] responsible girl. [Furthermore,] [t]hey must ask first, ‘Would you like to do that?’ … because they know that I have my opinion now. I have [a] stronger personality.”

This greater trust and ascription of responsibility were accompanied by another profound shift in Participant 6’s family dynamics: “my mum now, and my dad also, they felt that they are proud of their daughter. I mean, ‘She’s working. She has a good job. She’s doing her Masters.’”

In relation to the differences between Salalah and Muscat noted above, Participant 6 stated baldly that, as well as feeling proud of their daughter, her parents “were worried, because it’s a new atmosphere” at the University: “I didn’t study with boys before, and it’s a big problem here in Salalah”. She elaborated: “Because, you know, we cover our face[s]. We cover our bod[ies]. … [I]t’s a taboo [to be] with men in the same place. But, … after two months, three months, it became okay, [and it is] common now.” Moreover, “Here in Salalah we must cover our face[s]. We must cover our bod[ies]. So no one can see you except if he’s your brother or your cousin sometimes. But in Muscat no. It’s the opposite.”

More widely, Participant 6 differentiated explicitly between locally based customs that varied from place to place and over time on the one hand, and perceived formal religious requirements on the other hand. From this perspective she analysed the dress code for female Omanis in Salalah as follows:

It’s from years [ago]. You can say it’s [been] … one hundred years like this. It’s a norm. It’s not coming from Islam, no. Islam [doesn’t] tell us to cover all of these things. Just cover your hair and do whatever you want to do, unless … [those] things … would harm your behaviour. But, you know, society sometimes forces you to do something [in] the name of Islam.

Participant 7 proffered a somewhat different analysis of the complex relationship between religion and social change in Oman:

… if you go and search in the society in our religion, you have to learn. You have to learn. If you didn’t learn—because the religion supports that, people accept it. People will accept it if it’s from the religion. If religion did not allow it, they will say, “No”, and they will fight for a long time. But, because they allowed that, they [got] us to study. They allowed us to do it. So I think it depends. Our culture at the beginning [in relation to] girls, “Why is she going?”. But people say to them, “Yeah, religion … and the government allowed them [to be educated]”.

With regard to the paired ideas portrayed in Fig. 12.1, several of these ideas were canvassed in the selected data analysed in this section of the chapter. For instance, Article 12 of the Basic Law of the State (Sultan Qaboos, 1996) distilled complex moves from patriarchy to equality, while the late Sultan’s introduction of Omani Women’s National Day in 2007 constituted a decisive bridging between tradition and modernity. Moreover, the participants interpreted both these developments as ongoing shifts between community and society, and between tribalism and nationalism. Furthermore, individual participants varied in their constructions of how these broader changes influenced their respective family and individual relationships, as well as of the interplay between historical change and international change within their specific family and occupational contexts.

In terms of the chapter’s conceptual framework, the data analysis presented here corroborated Dervin’s (2016) insight that “One cannot meet a culture but people who (are made to) represent it—or rather represent imaginaries and representations of it” (Chap. 2). In diverse ways, each participant contributed to representing such “imaginaries and representations” of Omani culture and society and of the Islamic religion in ways that were meaningful to her. Similarly, this data analysis confirmed Dervin’s (2017) characterisation of critical interculturality “as a never-ending process of ideological struggle against social identities, unfair power differentials, discrimination and hurtful (and often disguised) discourses of (banal) nationalism, ethnocentrism, racism and other forms of -ism” (p. 1). The participants’ insights and reflections reported here highlighted how complex, contextualised, nuanced and subtle this “process of ideological struggle” is and also how heterogeneous it is even from the perspectives of the seven participants in this study. As we noted also when presenting the chapter’s conceptual framework, these findings contributed in turn to operationalising possibilities for ethical and rigorous contestations of cultural essentialism and hegemony, as well as for specific strategies for resisting and subverting exclusion and othering in varied forms, while acknowledging always the material constraints on and limitations of doing so.

More widely, it can be seen from this analysis that mobilising critical interculturality in this way to research within the educational margins affords new understandings of and strategies for communicating and articulating voices within those margins. In particular, this chapter has illustrated starkly the conceptual fluidity and the situated manifestations of gendered discourses and critical interculturality alike. While each of these theoretical resources contributed important insights to this analysis, what emerges equally significantly are the singularity and specificity of Dhofar and Oman as culturally, geographically and historically constituted contexts that helped to frame and constrain the study participants’ agential and intelligent engagements with the distinctive opportunities generated by their undergraduate experiences in learning English at Dhofar University .

Conclusion

This chapter has explored the experiences and perceptions of a group of female undergraduate students studying English at Dhofar University in Oman, against the backdrop of significant changes to traditional tribal and patriarchal culture in that nation. Critical interculturality (Dervin, 2016, 2017) has been confirmed as instructive in analysing the participants’ voices. At the same time, the lessons arising from that analysis include wider issues pertaining to education research, marginalisation and vocality.

Firstly, the complexity and diversity of the regional, national, community, family and personal contexts, exemplified in the paired ideas elaborated in Fig. 12.1, explain why education research projects resist easy analysis or superficial generalisation. On the contrary, the differences among the participants’ responses identified in the preceding section of this chapter underscore the continuing need to remain attentive to the nuances and subtleties of individual variations on aspirations, experiences and insights related to researching educational opportunities and outcomes.

Secondly, marginalisation emerges as a complicated and elusive phenomenon that evokes as many questions as it resolves. One such question revolves around the ethics and utility of identifying certain individuals and groups as “marginalised” (Danaher, 2000). For instance, with regard to academic publications dealing with such individuals and groups, “it behoves the authors to ensure that they do not deploy the discourse of ‘marginalization’ in ways that actually help to replicate the inequalities that they are seeking to make explicit and to contest” (Danaher, Cook, Danaher, Coombes, & Danaher, 2013, p. 4). This is on the basis that, “unless considerable care is taken, naming practices involved in researching marginalization can serve to perpetuate the apparently different and deficit dimensions of the lived experiences and perceived identities of individual members of particular communities” (Danaher et al., 2013, p. 4). It was for this reason that we referred in the introduction to this chapter to the study participants as “situatedly marginalised learners”, given that they would not necessarily identify themselves as “marginalised”, and also given that our analysis has complicated and problematised, rather than homogenised and simplified, these women’s educational experiences.

Thirdly and finally, this book’s focus on communicating and articulating voices in research projects dealing with learners on the educational margins, in the context of this chapter’s account of the Dhofari women’s experiences of English language undergraduate courses in Oman, demonstrates that, like marginalisation, vocality is far from being a homogeneous, singular or undifferentiated phenomenon. This was highlighted by the divergences among the participants’ reported interactions with their courses and within the posited impact of those interactions on their respective families. Relatedly, in some ways the voices of those family members were as significant as those of the participants, whose utterances in the semi-structured interviews reflected and refracted the varied and in some cases contradictory perspectives of different generations in a single family.

Overall, then, this particular account of researching cultural differences and intercultural experiences, grounded in Dhofari women’s understandings of their English language undergraduate courses, and informed by the concept of critical interculturality (Dervin, 2016, 2017), has much to teach us about learning, teaching and researching within the educational margins beyond the national boundaries of Oman.

References

Aikman, S., & Robinson-Pant, A. (2019). Indigenous women and adult learning: Towards a paradigm change? Studies in the Education of Adults, 51(2), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2019.1641906

Al Hasani, M. H. H. (2015). Women’s employment in Oman. Unpublished Doctor of Philosophy thesis, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, QLD, Australia.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burns, S., Coombes, P. N., Danaher, P. A., & Midgley, W. (2014, August 27). Educating Raya and educating Rita: Contextualising and diversifying transformative learning and feminist empowerment in pre-undergraduate preparatory writing programs in Oman and Australia. Paper presented at the international conference on writing research, Roeterseiland, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Danaher, M. J. M., Cook, J. R., Danaher, G. R., Coombes, P. N., & Danaher, P. A. (2013). Researching education with marginalized communities. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Danaher, P. A. (2000). What’s in a name? The “marginalization” of itinerant people. Journal of Nomadic Studies, 3, 67–71.

Dervin, F. (2016). Interculturality in education: A theoretical and methodological toolkit. Basingstoke: Palgrave Pivot/Palgrave Macmillan.

Dervin, F. (2017). Critical interculturality: Lectures and notes. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Finlay, L. (2009). Debating phenomenological research methods. Phenomenology & Practice, 3(1), 6–25.

Greenfield, P. M. (2009, March). Linking social change and developmental change: Shifting pathways of human development. Developmental Psychology, 45(2), 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014726

Jackson, S. (2004). Differently academic? Developing lifelong learning for women in higher education (Lifelong learning book series). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Lee, R., & Kim, J. (2018, July). Women and/or immigrants: A feminist reading on the marginalised adult learners in Korean lifelong learning policy and practice. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 58(2), 184–208.

Petersen, J. E. (2016). Oman in the twentieth century: Political foundations of an emerging state. London: Routledge.

Shehadeh, H. (2010). Omani women on the march for equality and broader opportunities. Middle East Online.

Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. London: Sage Publications.

Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2003). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 51–80). London: Sage Publications.

Sultan Qaboos. (1996). Royal decree no. 101/96. Retrieved from https://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/om/om019en.pdf

Acknowledgements

The first-named author is extremely grateful to the female undergraduate Omani students who participated in her doctoral study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Burns, S., Danaher, P.A. (2020). Mobilising Critical Interculturality in Researching Within the Educational Margins: Lessons from Dhofari Women’s Experiences of English Language Undergraduate Courses in Oman. In: Mulligan, D.L., Danaher, P.A. (eds) Researching Within the Educational Margins. Palgrave Studies in Education Research Methods. Palgrave Pivot, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48845-1_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48845-1_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Pivot, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-48844-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-48845-1

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)