Abstract

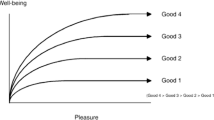

Hasko Von Kriegstein’s chapter aims to sketch a comprehensive theory of well-being based on a small set of principles of harmony. It is called harmonism. Here, Von Kriegstein develops a notion of harmony between mind and world that has three aspects. First, there is a correspondence between mind and world in the sense that events in the world match the content of our mental states. Second, there is a positive orientation toward the world, meaning that we have pro-attitudes toward the world we find ourselves in. Third, there is a fitting response to the world. Taken together these three aspects make up an ideal of being attuned to, or at home in, the world. Such harmony between mind and world constitutes well-being. These principles have the potential to provide a unified explanation of many items traditionally found on ‘objective lists’ of human values, such as achievement, knowledge, pleasure, self-respect, and virtue. The three principles can be understood as different aspects of a coherent ethical ideal of harmony.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Cf. Belshaw (2014, 580).

- 2.

Cf. the Stoic contention that sometimes even a choice like ending one’s own life can be according to nature (Baltzly 2019, section 5).

- 3.

- 4.

This notion is more or less equivalent to Zimmerman’s concrete states (Zimmerman 2001, 52–3).

- 5.

See, for example, Crisp’s debunking arguments against accomplishment (Crisp 2006b, 637–42).

- 6.

This assumes the object interpretation of desire-satisfactionism (Van Weelden 2019, 138).

- 7.

Cf. Rice (2013, 200).

- 8.

- 9.

- 10.

Cf. Lin (2017).

- 11.

Cf. Lin (2017).

- 12.

Relatedly, many have noted that some forms of hedonism are essentially one-item objective-list theories (e.g. Fletcher 2013, 206).

- 13.

Cf. Hurka (2004, 252).

- 14.

- 15.

- 16.

Cf. Searle (1983, 10–1).

- 17.

Cf. Keller (2009, 668).

- 18.

I would say, however, that the locution pre-established harmony is misleading insofar as it obscures the fact that the pre-establishment on God’s part is a necessary condition for there to be harmony at all rather than mere correspondence.

- 19.

This is not to endorse a correspondence theory of truth. Rather, it is to endorse the truism that truth is objective, that is, that true beliefs ‘portray the world as it is’ (Lynch 2004, 12). Any theory of truth (and of knowledge) will have to capture that thought.

- 20.

- 21.

- 22.

- 23.

Cf. Griffin (1986, 17).

- 24.

- 25.

Cf. Stalnaker (1984, 15).

- 26.

- 27.

- 28.

- 29.

Adapting one’s pro-attitudes is not necessarily a prudent strategy. Insofar as it might undermine one’s motivation to improve one’s circumstances it might keep one from improving one’s well-being more substantially than adapting one’s pro-attitudes does.

- 30.

Cf. Heathwood (2007).

- 31.

- 32.

- 33.

- 34.

A fortiori, it is not a subjectivist theory in the sense that would require every valuable event to be the content of a pro-attitude (Van Weelden 2019, 147–9).

- 35.

In cases of outrageous moral violations our indignation may, of course, quite rightfully overpower any such pity, however appropriate.

- 36.

Cf. Maguire (2018, 793).

- 37.

Cf. Sepielli (2009, 8).

- 38.

See Nozick (1981, 427 for NACP; 432 for POP; 433 for FRP).

References

Anderson, Elizabeth. 1993. Value in Ethics and Economics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Aristotle. 1984. Nicomachean Ethics. Trans. David Ross and James Urmson. In The Complete Works of Aristotle, ed. Jonathan Barnes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Arneson, Richard. 1999. Human Flourishing versus Desire Satisfaction. Social Philosophy and Policy 16 (1): 113–142.

Aydede, Murat. 2014. How to Unify Theories of Sensory Pleasure: An Adverbialist Proposal. Review of Philosophy and Psychology 5 (1): 119–133.

Baltzly, Dirk. 2019. Stoicism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/stoicism/.

Belshaw, Christopher. 2014. What’s Wrong with the Experience Machine? European Journal of Philosophy 22 (4): 573–592.

Bradford, Gwen. 2015. Achievement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brentano, Franz. 1889. Vom Ursprung Sittlicher Erkenntnis. Leipzig: Von Duncker & Humblot.

Broad, Charles Dunbar. 1930. Five Types of Ethical Theory. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

Bykvist, Krister. 2002. Sumner on Desires and Well-Being. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 32 (4): 475–490.

Chisholm, Roderick. 2013. The Defeat of Good and Evil. The American Philosophical Association Centennial Series 42: 533–548.

Crisp, Roger. 2006a. Reasons and the Good. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

———. 2006b. Hedonism Reconsidered. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 73 (3): 619–645.

Darwall, Stephen. 2004. Welfare and Rational Care. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dorsey, Dale. 2010. Three Arguments for Perfectionism. Noûs 44 (1): 59–79.

———. 2012. Subjectivism without Desire. Philosophical Review 121 (3): 407–442.

Ewing, Alfred Cyril. 1939. A Suggested Non-Naturalistic Analysis of Good. Mind 48 (189): 1–22.

———. 1953. Ethics. London: English Universities Press.

Feldman, Fred. 2004. Pleasure and the Good Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fletcher, Guy. 2013. A Fresh Start for the Objective-List Theory of Well-Being. Utilitas 25 (2): 206–220.

Griffin, James. 1986. Well-Being: Its Meaning, Measurement and Moral Importance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Haybron, Daniel. 2008. The Pursuit of Unhappiness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heathwood, Chris. 2007. The Reduction of Sensory Pleasure to Desire. Philosophical Studies 133 (1): 23–44.

———. 2017. Which Desires Are Relevant to Well-Being? Noûs. https://doi.org/10.1111/nous.12232

Hurka, Thomas. 1993. Perfectionism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2001. Virtue, Vice, and Value. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2004. Normative Ethics: Back to the Future. In The Future for Philosophy, ed. Brian Leiter, 246–264. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

———. 2011. The Best Things in Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kagan, Shelly. 2015. An Introduction to Ill-Being. Oxford Studies in Normative Ethics 4: 261–288.

Keller, Simon. 2004. Welfare and the Achievement of Goals. Philosophical Studies 121 (1): 27–41.

———. 2009. Welfare as Success. Noûs 43 (4): 656–683.

Khader, Serene. 2011. Adaptive Preferences and Women’s Empowerment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kim, Jaegwon. 1976. Events as Property Exemplifications. In Action Theory, 159–177. Dordrecht: Springer.

Lin, Eden. (2017). Enumeration and explanation in theories of welfare. Analysis 77(1), 65–73.

Long, Anthony Arthur, and David Sedley. 1987. The Hellenistic Philosophers. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lynch, Michael. 2004. True to Life. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Maguire, Barry. 2018. There are No Reasons for Affective Attitudes. Mind 127 (507): 779–805.

Mathison, Eric. 2018. Asymmetries and Ill-Being. PhD diss., University of Toronto.

Moore, George Edward. 1901. Principia Ethica. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Navarro, Jesús. 2015. No Achievement Beyond Intention. Synthese 192 (10): 3339–3369.

Nozick, Robert. 1974. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. New York: Basic Books.

———. 1981. Philosophical Explanations. Belknap: Cambridge.

Overvold, Mark. 1980. Self-Interest and the Concept of Self-Sacrifice. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 10 (1): 105–118.

Parfit, Derek. 1984. Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Railton, Peter. 1986. Fact and Value. Philosophical Topics 14: 5–31.

Rice, Christopher. 2013. Defending the Objective List Theory of Well-Being. Ratio 26 (2): 196–211.

Rosati, Connie. 1996. Internalism and the Good for a Person. Ethics 106 (2): 297–326.

Scanlon, Thomas Michael. 1998. What We Owe to Each Other. Belknap: Harvard.

Searle, John. 1983. Intentionality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sen, Amartya. 1987. On Ethics and Economics. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Sepielli, Andrew (2009). What to do when you don’t know what to do. Oxford studies in metaethics, 4: 5–28.

Stalnaker, Robert. 1984. Inquiry. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sumner, Wayne. 1996. Welfare, Happiness, and Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Weelden, Joseph. 2019. On Two Interpretations of the Desire-Satisfaction Theory of Prudential Value. Utilitas 31 (2): 137–156.

Von Kriegstein, Hasko. 2017. Effort and Achievement. Utilitas 29 (1): 27–51.

———. 2018. Scales for Scope: A New Solution to the Scope Problem for Pro-Attitude-Based Well-Being. Utilitas 30 (4): 417–438.

———. 2019. Succeeding Competently: Towards an Anti-Luck Condition for Achievement. Canadian Journal of Philosophy 49 (3): 394–418.

Wiggins, David. 1987. Needs, Values, Truth: Essays in the Philosophy of Value. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wilson, Timothy, and Daniel Gilbert. 2003. Affective Forecasting. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 35: 345–411.

Zimmerman, Michael. 2001. The Nature of Intrinsic Value. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

Acknowledgement

In thinking about this project I have greatly profited from conversations with a large number of colleagues. I remember the following individuals making particularly helpful comments at various stages: Dani Attas, Gwen Bradford, Kenneth Boyd, David Enoch, Avigail Ferdman, Diana Heney, Thomas Hurka, David Kaspar, Ittay Nissan-Rozen, Devlin Russell, Sergio Tenenbaum, Andreas T. Schmidt, Wayne Sumner, Ulla Wessels.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

von Kriegstein, H. (2020). Well-Being as Harmony. In: Kaspar, D. (eds) Explorations in Ethics. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48051-6_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48051-6_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-48050-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-48051-6

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)