Abstract

This chapter examines the determinants of entrepreneurial intentions of university students in an African university setting. The case illustration is based upon a sample of 261 university students at the University of Education, Winneba, Kumasi (Ghana). The chapter highlights the findings from a quantitative assessment of the determinants of entrepreneurial intentions among university students in this African setting. The study found high risk taking, support from contextual factors and perceived behavioural control as having strong influences on the entrepreneurial intentions of the investigated students. The findings have implications for the development of entrepreneurship education in Ghana specifically, and African universities more widely.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Due to its contribution to economic growth , innovativeness, job creation and wealth creation, entrepreneurship has gained global attention across most sectors from agriculture, through media and entertainment to higher education (Igwe et al. 2020; Taura et al. 2019; Buame 1996). Ghana as a developing nation encourages entrepreneurial activities in various ways due to the ever-growing undergraduate and/or graduate unemployment challenge. Universities and the wider tertiary education institutions across the country offer some form of entrepreneurship in the curriculum either as a full programme or as part of the required course.

In the past two decades, higher education has seen considerable growth both in the development of entrepreneurship as a subject and in the number of entrepreneurship courses offered (Bell 2015) and these courses are largely found in business schools within higher education institutions (HEIs) (Collins et al. 2006; Madichie and Fiberesima 2019; Madichie and Gbadamosi 2017; Fantazy and Madichie 2015; Healey 2019). The aim is to impart entrepreneurial skills among university students before graduation. Consequently, the solution to unemployment and economic problems would drastically reduce if not be eliminated. Outside the academic environment, the Government of Ghana has through some initiatives such as the Youth Enterprise Support (YES) among others encouraged entrepreneurship in order to address the challenges of youth unemployment.

Much of the literature on entrepreneurship in Ghana has concentrated on the development of formal or informal entrepreneur with their respondents being entrepreneurs (see Adom and Williams 2012; Black and Castaldo 2009; Buame 1996; Robson et al. 2009). Lee et al. (2011) argue that recognising the factors that influence entrepreneurial intentions represents a central component of studying the new business creation process. To this end, academic institutions are encouraged to investigate and understand the factors that determine entrepreneurial intentions (Maes et al. 2014). Whereas there is a great body of literature with respect to investigation of entrepreneurial intentions, there is paucity of research with respect to factors that determine the intention of students to undertake an entrepreneurial activity, particularly in the Ghanaian context.

The scant nature of the literature on the Ghanaian context, and especially in relation to the higher education sector, renders the study worthy of attention. In this regard, this chapter aims at identifying factors that predict entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Ghana.

Theoretical Background

Theory of Planned behaviour (TPB) is a widely accepted theory in psychology, which sets out to predict and explain human behaviour. This chapter is premised on the backdrop of TPB proposed by Ajzen (1985, 1991). The TPB is used as a theory for this study in that it seeks to present and explain the model that allows the understanding of the influence of attitudes and personal determinants on intentions to undertake an entrepreneurial venture (Kalafatis et al. 1999). This theory agrees that the best way for identifying the actions of people starting their own business is to find out if they intend to (Van Gelderen et al. 2015).

The TPB by far has become one of the most frequently cited and influential models in predicting human social behaviour (Ajzen 2011). According to Teo and Lee (2010), this was, however, an extension of Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) espoused by Ajzen and Fishbein (1980). Hobbs et al. (2013) contend that the TPB is a parsimonious theory, which identifies two proximal predictors of behaviour: intention and perceived behavioural control (PBC). The PBC was introduced in order to complement the other two components proposed in the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Ajzen 1991).

As reported in Teo and Lee (2010), Ajzen (1991) explained, “A person’s action is determined by behavioral intentions, which in turn are influenced by an attitude toward the behavior and subjective norms”. To predict behaviour, the theory argues that the underlying attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control play an important role. Miranda et al. (2017) added that with the TPB, the behaviour of a person is directly influenced by the intention of the person to perform (or not perform) that behaviour. The intention to perform such behaviour also depends on three major elements: entrepreneurial attitude, the subjective norm and PBC (Miranda et al. 2017). A meta-analytical assessment by Schlaegel and Koenig (2014) also concludes that the drivers of entrepreneurial intentions (EI) are attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control.

The theory has been shown to be very much relevant in the academic setting (e.g. Miranda et al. 2017; Obschonka et al. 2012, 2015; Autio et al. 2001; Peng et al. 2012; Aslam et al. 2012; Goethner et al. 2012). Hobbs et al. (2013) also echoed Ajzen (1991) that intention is itself predicted by attitudes towards the target behaviour, subjective norm, beliefs and PBC. In the work of Demir (2010), Ajzen (1991) reportedly postulated that “as a general rule, the more favourable the attitude and subjective norm with respect to behaviour, and the greater the perceived behavioural control, the stronger should be an individual’s intention to perform the behaviour under consideration”. It is for this reason that this study adds the elements of the theory, thus, attitudes, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control among other factors that trigger entrepreneurial intentions among university students in Ghana.

Ajzen (2011), however, conceded that the earlier handlings of the theories of reasoned action and planned behaviour (Ajzen 1991; Ajzen and Fishbein 1980) created the possibility of including additional predictors of intentions. The author further argued that the TPB was developed in this manner by adding perceived behavioural control to the original theory of reasoned action (TRA). This study proposes some additional constructs as predictors of entrepreneurial intentions.

Proposition Development

Citing Allport (1935), Paula and Shrivatavab (2016) defined attitude as a “mental and neural state of exerting readiness, exerting a directive or dynamic influence upon the individuals with regard to all objectives and situations”. An attitude towards a particular behaviour indicates the magnitude of a person’s favourable or unfavourable evaluation of the behaviour in question (Ajzen 1991, 2005). The intentions of a person to undertake a particular behaviour are influenced by the attitude regarding that behaviour. In their study, Yıldırıma et al. (2016) found that university students’ attitude towards behaviour loaded high on the factor, which indicates the extent of its significance. Van Gelderen et al. (2008) in their work on entrepreneurial intention using the TPB established that entrepreneurial intentions of students are influenced by their attitudes towards entrepreneurship. Positive attitude towards behaviour is found to improve on the entrepreneurial intentions of an individual (see Goethner et al. 2012; Kautonen et al. 2011; Autio et al. 2001). The work of Demir (2010) established a significant relationship between attitude and intention. In their study on entrepreneurship education at the university level, Küttima et al. (2014) established a significant relationship between attitude and intention. Hence, we hypothesise that:

Proposition 1: Attitude Is Related to Entrepreneurial Intentions

Subjective Norm (SN)

Subjective norm refers to the perceived social pressure to undertake a particular behaviour or otherwise (Ajzen 1991, 2002). Maresch et al. (2016) argue that social norms relate to the perception an individual has about the opinions of social reference groups (such as family and friends), which could determine the intention of the said individual to undertake a behaviour. They added further that a person is highly motivated to start a business when the reference group’s opinion is encouraging. Franke and Lüthje (2004) expressed the optimism that academic context is an important part of the students’ environment. Armitage and Conner (2001) suggest that the subjective norm construct is a generally weak predictor of intentions. Maresch et al. (2016) also concluded that the subjective norm negatively correlates entrepreneurial intentions for science and engineering students. However, Yıldırıma et al. (2016) report that university activities of “initiation, development and support” by some means “trigger” the intentions of students to become entrepreneurs and encourages them in the direction of business start-up plans. In this study, therefore, SN is used to refer to the academic environment of the student, the encouragement the student gets to start a business. Consequently, we hypothesise that:

Proposition 2: Social Norm Is Related to Entrepreneurial Intentions

Perceived Behavioural Control (PBC)

PBC as explained by Ajzen (1991) refers to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behaviour and it is assumed to reflect past experiences as well as anticipated impediments. Demir (2010) also views PBC as an individual’s perceived easiness or difficulty of performing a behaviour. PBC plays a central role in the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen 1991) and consequently predicts entrepreneurial intentions (Ajzen 2011). PBC was found to have a significant effect on respondents’ intentions to use the internet (Demir 2010). The work of Küttima et al. (2014) on entrepreneurship education at the university also established a substantial relationship between PBC and entrepreneurial intentions. In a study conducted by Murugesan and Jayavelu (2015), a significant relationship was established between PBC and entrepreneurial intentions. Therefore, we hypothesise that:

Proposition 3: Perceived Behavioural Control Is Related to Entrepreneurial Intentions

Internal Locus of Control

Rotter (1954) explored personality traits by using the concept of locus of control, asserting that people with an internal locus of control believe that success and failure depend on the amount of effort invested and that they can control their fate (Hsio et al. 2016). By contrast, people with an external locus of control believe that their fate is determined by chance or luck and is not within their control (Lii and Wong 2008). Luthans et al. (2006) indicated that people with an internal locus of control tend to positively face challenges and obstacles, resolving problems by seeking constructive solutions. People with an external locus of control exhibit higher achievement motivation compared with people with an internal locus of control (Hsio et al. 2016). Consequently, they are more willing to learn and enhance their capabilities and knowledge when encountering challenges (Johnson 1980). Compared with other methods for classifying personality traits, locus of control typically enables effectively distinguishing between subjects; thus, people with an internal locus of control and people with an external locus of control are commonly recruited as research subjects in studies related to psychology and applied psychology for analysing various personality traits (Judge and Bono 2001).

Proposition 4: Internal Locus of Control Is Related to Entrepreneurial Intentions

Risk Taking

Risk reflects the degree of uncertainty and potential loss associated with outcomes which may follow from a given behaviour or set of behaviours (Forlani and Mullins 2000). Yates and Stone (1992) opine that the basic element of risk construction can be identified as potential losses and the significance of those losses. According to Kvietok (2013), the decision to take on the business risk is symptomatic of a certain type of people. A significant part of the motivation to take risks in business follows from the success motivation. To achieve the set goals, successful people are willing to take on reasonable risks associated with feedback about the level of achieved results.

Knörr et al. (2013) mentioned creativity, risk taking and independence increase the probability of becoming an entrepreneur and these characteristics decrease the probability of becoming an employee. Similarly, Almeida et al. (2014) perceived entrepreneurs primarily as enterprising and creative, and to some degree as social and investigative (Kozubíková et al. 2015). According to Beugelsdijk and Noorderhaven (2005), entrepreneurs differ from the general population and from paid employees in that they are more individually oriented and have a greater individual responsibility and effort (Kozubíková et al. 2015). In this context, Omerzel and Kušce (2013) indicate that the inclination to take risks, self-efficacy and the need for independence are the most important factors affecting personal performance of the businessman. Fairlie and Holleran (2012) assert that people with a higher tolerance for risk use more of their professional knowledge from the past than personalities with a lower tolerance for risk. In relation to that Cassar (2014) states that these people have realistic expectations in business, and this advantage is manifested mainly in areas with a high degree of uncertainty, such as high technology (Kozubíková et al. 2015). Thus we hypothesise that:

Proposition 5: Risk Taking Is Related to Entrepreneurial Intentions

Favourable Support from Contextual Factors

Favourable support refers to the support the student gets from the academic or business environment to start a business. Lüthje and Franke (2003) concluded that universities are in a position to shape and encourage entrepreneurial intentions. The work of Schwarz et al. (2009) on students’ entrepreneurial intent found that a positive perception of university actions to encourage entrepreneurship hints at a stronger willingness to start up an own business in the future. Siegel and Phan (2005) postulated that training for entrepreneurship and contact with entities that provide support for entrepreneurs have a tendency to encourage the willingness to start a business. In a study conducted by Rauch and Hulsink (2015) it was stated that entrepreneurial training with access to resources makes it possible for an individual to yearn for a business start-up. Prior studies (Autio et al. 1997; Yıldırıma et al. 2016; Fantazy and Madichie 2015; Healey 2019; Madichie 2015; Madichie 2013) have shown that the support received from the university environment tends to account for one of the factors influencing students’ intention to become entrepreneurial. For this reason, we hypothesise that:

Proposition 6: Favourable Support Is Related to Entrepreneurial Intentions

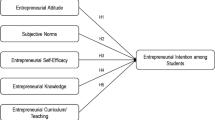

Figure 8.1 presents the model that was explored in this study. It describes the constructs that influence entrepreneurial intention.

Methodology

In this section, we first present a background into the origins of the case university before we go on to explain the survey process and development of the constructs for the study.

Case Background

The University of Education, Winneba (UEW), was established in September 1992 as a University College under the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) Law 322 to train teachers. On 14 May 2004, the University of Education Act (i.e. Act No. 672) was enacted to upgrade the status of the University College of Education of Winneba to the status of a full university (www.uew.edu.gh). The University College of Education of Winneba brought together seven diploma awarding colleges located in different towns under one umbrella institution. These colleges were the Advanced Teacher Training College, the Specialist Training College and the National Academy of Music, all at Winneba; the School of Ghana Languages, Ajumako; the College of Special Education, Akwapim-Mampong; the Advanced Technical Training College, Kumasi; and the St. Andrews Agricultural Training College, Mampong-Ashanti. The University has four satellite campuses that together form the University of Education. These campuses are the Colleges of Technical Education located at Kumasi, the College of Agriculture Education located at Mampong, the College of Languages Education located at Ajumako and the Winneba Campus where the main administration is also located.

The Survey Process

Based on a survey of university students in the Ghanaian setting, using self-administered questionnaires on 261 respondents, a range of constructs are developed. These constructs (with their respective indicators) in the study were developed from the review of literature, and these include attitude, perceived behavioural control, social norm, risk taking, internal locus of control, favourable support (i.e. independent variables). The dependent variable for the study (entrepreneurial intention) was also developed from previous studies. The partial least squares (PLS) technique was employed to test the model and this resulted in the use of the Smart PLS software (Ferreira et al. 2012). The PLS method is particularly beneficial in predicting dependent variables from a (very) large set of independent variables (i.e. predictors) (Abdi 2003). Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted first to determine the strength of each statement on a construct they supposed to measure. To ensure a better model performance, factors with loading below 0.6 were dropped, which resulted in most of the constructs having only two factors. In all, 271 respondents made up of university students (Business Administration) were sampled. Through data cleaning, the sample reduced to 261. The smartpls developed by Ringle et al. (2015) was used for the analysis.

Discussion of Findings

According to Gartner et al. (1992) entrepreneurship is the process of organisational emergence. It is also seen as the innovative and creative process with the potential of value addition to products, which would go a long way to improve productivity and to develop the economy (Guerrero et al. 2008). Entrepreneurial intention has also received much attention in the literature. It has been used in the literature to refer to the personal orientations, desires or interest which would result in the creation of a business (Thompson 2009). Bird (1988) considers entrepreneurial intentions as the state of the mind of the individual which directs them towards the creation of new business.

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

From Table 8.1 it can be seen that male respondents constituted 158 (62.0%) of valid respondents while females were 97 (38%) of valid respondents. This is not surprising because more males are admitted into universities than females. The marital status of respondents revealed that 90.3% were single compared to 9.3% of the valid respondents who were married. This is again expected as most students at the university are direct intakes from the secondary schools and are therefore not employed. Respondents with family members or friends who were self-employed were 72.5% of the valid respondents with 27.5% not coming from families with a business background. This is very reassuring as this increases the likelihood of producing future entrepreneurs.

The mean age of respondents from Table 8.2 is about 25, which is not surprising given the fact that university students constituted the sampling unit. The study revealed a minimum age of 20 and a maximum of 39.

Reliability and Validity of Scales

Before establishing the relationship between entrepreneurial intention and the independent variables in the study, the scale used must pass the test of reliability and validity. To test for reliability, Cronbach Alpha, Composite Reliability and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were used. Before examining the relationship between the key variables, reliability and validity tests were performed. Reliability tests were examined using the Cronbach’s alpha and the composite reliability statistics. On the other hand, construct validity and discriminant validity were also checked to confirm the overall validity of scales. To pass the test of reliability a factor must have a value above 0.7 for Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability and above 0.5 for AVE. The results from Table 8.3 showed that all factors passed the test of reliability based on composite reliability and AVE but most failed the test based on Cronbach’s alpha. However, once the test of AVE was achieved, the factors could be deemed reliable.

From Table 8.3, it is clear that all the factors loaded higher than any other factor on their scales. Attitude on its scale had a value of about 0.9, which is higher than any other construct on that scale. As Ferreira et al. (2012) argued that the composite reliability is a better measure to Cronbach’s alpha due to the latter’s assumption of parallel measures, which represent a lower bound estimate of internal consistency. To test for validity, a discriminant analysis was performed and the result presented in Table 8.4. Discriminant analysis requires a factor to correlate higher than with any other construct on its scale (Messick 1988). As can be seen in Table 8.4, EI has a value of 0.8, FS (0.8), RT (0.8), ILC (0.9), PBC (0.8) and SN (0.9).

Regression Results

To assess the relationship between entrepreneurial intention and a set of independent factors, the partial least square model was used and the resultant bootstrap presented in Table 8.5.

The results from Table 8.5 show that favourable support, risk taking and perceived behavioural control were the factors that significantly and positively influence entrepreneurial intention. Favourable support is said to be significant in determining entrepreneurial intentions of Ghanaian students. This relates to the positive image Ghanaian entrepreneurs enjoy as well as the availability of qualified consultants and service support for new enterprise. The university environment also plays a major role here as the work of Schwarz et al. (2009) concludes that students’ willingness to start a business largely emanates from the actions of universities in encouraging entrepreneurship. Similar findings were made by Siegel and Phan (2005) who added that entities that provide support for entrepreneurs have the tendency to encourage the willingness to start a business.

The findings from the study further suggest that risk taking plays a major role in determining the intentions of students to start a business. Respondents are ready to undertake behaviour with an uncertain outcome. In this regard, students are ready to try new things and have taken at least a risk in recent times. One of the surest factors that increase the probability of starting up a business is risk taking, which decreases the likelihood of becoming an employee (Knörr et al. 2013; Omerzel and Kušce 2013). Furthermore, there are indications that PBC significantly influences students’ intention to start a business. This is associated with the belief in individual skills and capabilities to succeed as an entrepreneur, which makes them perceive easiness in starting up a business. Prior studies (Murugesan and Jayavelu 2015; Küttima et al. 2014; Demir 2010) have variously confirmed the significance of PBC on entrepreneurial intentions. The implication is that perceived behavioural control can be a strong measure for one’s ability to be independent (i.e. being on one’s own in terms of taking business initiatives and creating value for society).

Conclusions and Implications

The main focus of this chapter was to highlight factors contributing to the entrepreneurial intentions of university students taken from the purview of the University of Education, Winneba. The theory of planned behaviour was used as the backdrop in an attempt to explain behaviour and entrepreneurial intentions of students. The findings indicate that, first, risk taking, second, favourable support from contextual factors, and, third, perceived behavioural control all proved significant in determining entrepreneurial intentions of students.

These findings are consistent with what is already reasonably well established in the literature—that is, favourable support has both a practical and a theoretical impact on entrepreneurial development. In an enabling environment where there is access to credit at lower cost for start-ups, ease of business registration, protection of intellectual property (among others), people will be attracted to develop their entrepreneurial skills and potential. Risk taking is also a key element in determining who can become an entrepreneur. The business environment is full of uncertainty and risk, and one’s ability to take risk amid uncertainty can definitely be a strong measure in determining entrepreneurial intentions.

In recognition of this, universities are well advised to initiate programmes that nurture and support students with identifiable entrepreneurial intentions to actualise their aspirations to the betterment of the wider society. However, considering the unresolved distinction between “intentions to start a business” and “actually starting a business”, future research could further interrogate the root causes of this disconnection. Overall, this chapter has implications for theory and practice—especially for universities already teaching, or planning to teach, courses in entrepreneurship in Africa and beyond.

References

Abdi, H. 2003. PLS-Regression; Multivariate Analysis. In Encyclopedia for Research Methods for the Social Sciences, ed. M. Lewis-Beck, A. Bryman, and T. Futing. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Adom, K., and C.C. Williams. 2012. Evaluating the Motives of Informal Entrepreneurs in Koforidua Ghana. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship (JDE) 17 (1): 1–17.

Ajzen, I. 1985. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action-Control: From Cognition to Behaviour, ed. J. Kuhl and J. Beckmann, 11–39. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

———. 1991. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and the Human Decision Process 50: 179–211.

———. 2002. Residual Effects of Past on Later Behavior: Habituation and Reasoned Action Perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Review 6 (2): 107–122.

———. 2011. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psychology and Health 26 (9): 1113–1127.

Ajzen, I., and M. Fishbein. 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Allport, G.W. 1935. Attitude. In Handbook of MA, ed. C. Murchison, 798–884. Worcester: Clark University.

Almeida, P.I.L., G. Ahmetoglu, and T. Chamorro-Premuzic. 2014. Who Wants to Be an Entrepreneur? The Relationship Between Vocational Interests and Individual Differences in Entrepreneurship. Journal of Career Assessment 22 (1): 102–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072713492923.

Armitage, C.J., and M. Conner. 2001. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Metaanalytic Review. British Journal of Social Psychology 40: 471–499.

Aslam, T.M., A.S. Awan, and T.M. Khan. 2012. Entrepreneurial Intentions Among University Students of Punjab a Province of Pakistan. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 2 (14): 114–120.

Autio, E., R.H. Keeley, and M. Klofsten. 1997. Entrepreneurial Intent Among Students: Testing an Intent Model in Asia, Scandinavia, and USA. In Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research. Wellesley: Babson College.

Autio, E., R.H. Keeley, M. Klofsten, G.C. Parker, and M. Hay. 2001. Entrepreneurial Intent Among Students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterprise and Innovation Management Studies 2 (2): 145–160.

Bell, R. 2015. Developing the Next Generation of Entrepreneurs: Giving Students the Opportunity to Gain Experience and Thrive. The International Journal of Management Education 13: 37–47.

Beugelsdijk, S., and N. Noorderhaven. 2005. Personality Characteristics of Self-Employed; An Empirical Study. Small Business Economics 24 (2): 159–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-003-3806-3.

Bird, B. 1988. Implementing Entrepreneurial Ideas: The Case for Intentions. Academy of Management Review 13: 442–454.

Black, R., and A. Castaldo. 2009. Return Migration and Entrepreneurship in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire: The Role of Capital Transfers. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 100 (1): 44–58.

Buame, S.K. 1996. Entrepreneurship: A Contextual Perspective. Discourses and Praxis of Entrepreneurial Activities Within the Institutional Context of Ghana. In Lund Studies in Economics and Management, 28.

Cassar, G. 2014. Industry and Startup Experience on Entrepreneur Forecast Performance in New Firms. Journal of Business Venturing 29 (1): 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.busvent.2012.10.002.

Chen, Y. 2010. Does Entrepreneurship Education Matter to Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention? A Chinese Perspective. Paper presented at the Second International Conference on Information Science and Engineering, China.

Collins, L.A., A.J. Smith, and P.D. Hannon. 2006. Applying a Synergistic Learning Approach in Entrepreneurship Education. Management Learning 37 (3): 335–354.

Demir, K. 2010. Predictors of Internet Use for the Professional Development of Teachers: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Teacher Development 14 (1): 1–14.

Fairlie, R.W., and W. Holleran. 2012. Entrepreneurship Training, Risk Aversion and Other Personality Traits: Evidence from a Random Experiment. Journal of Economic Psychology 33: 366–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.02.001.

Fantazy, K., and N.O. Madichie. 2015. Standardisation/Adaptation of the Curriculum–Relevance of ‘Western’ Business Textbooks for the MENA. International Journal of Business & Emerging Markets 7 (4): 380–395.

Ferreira, J.J., M.L. Raposo, R.G. Rodrigues, A. Dinis, and do Paço A. 2012. A Model of Entrepreneurial Intention: An Application of the Psychological and Behavioral Approaches. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 19 (3): 424–440.

Forlani, D., and J.W. Mullins. 2000. Perceived Risks and Choices in Entrepreneurs’ New Venture Decisions. Journal of Business Venturing 15: 305–322.

Franke, N., and C. Lüthje. 2004. Entrepreneurial Intentions of Business Students—A Benchmarking Study. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management 1 (03): 269–288.

Gartner, W.B., B.J. Bird, and J.A. Starr. 1992. Acting as If: Differentiating Entrepreneurial from Organizational Behaviour. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 16: 13–31.

Goethner, M., M. Obschonka, R.K. Silbereisen, and U. Cantner. 2012. Scientists’ Transition to Academic Entrepreneurship: Economic and Psychological Determinants. Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (3): 628–641.

Guerrero, M., J. Rialp, and D. Urbano. 2008. The Impact of Desirability and Feasibility on Entrepreneurial Intentions: A Structural Equation Model. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 4 (1): 35–50.

Healey, N.M. 2019. The End of Transnational Education? The View from the UK. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education: 1–11.

Hobbs, N., D. Dixon, M. Johnston, and K. Howie. 2013. Can the Theory of Planned Behaviour Predict the Physical Activity Behaviour of Individuals? Psychology & Health 28 (3): 234–249.

Hsio, C., Y. Lee, and H. Chen. 2016. The Effects of Internal Locus of Control on Entrepreneurship: The Mediating Mechanisms of Social Capital and Human Capital. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 27 (11): 1158–1172.

Igwe, P., D. Hack-Polay, J. Mendy, T. Fuller, and D. Lock. 2020. Improving Higher Education Standards Through Reengineering in West African Universities: A Case study of Nigeria. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1698534.

Johnson, R.C. 1980. Summing Up Review of Personality and Learning Theory, Vol. 1: The Structure of Personality in Its Environment. Contemporary Psychology 25: 299–300.

Judge, T.A., and J.E. Bono. 2001. Relationship of Core Self-Evaluations Traits-Self-Esteem, Generalized Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and Emotional Stability-with Job Satisfaction and Job Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 86: 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.80.

Kalafatis, S.P., M. Pollard, R. East, and M.H. Tsogas. 1999. Green Marketing and Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Cross-market Examination. Journal of Consumer Marketing 16 (5): 441–460.

Kautonen, T., E.T. Tornikoski, and E. Kibler. 2011. Entrepreneurial Intentions in the Third Age: the Impact of Perceived Age Norms. Small business economics 37 (2): 219–234.

Knörr, H., C. Alvarez, and D. Urbano. 2013. Entrepreneurs or Employees: A Cross-Cultural Cognitive Analysis. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 9 (2): 273–294.

Kozubíková, L., J. Belás, Y. Bilan, and P. Bartoš. 2015. Personal Characteristics of Entrepreneurs in the Context of Perception and Management of Business Risk in the SME Segment. Economics and Sociology 8 (1): 41–54. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2015/8-1/4.

Küttima, M., M. Kallastea, U. Venesaara, and A. Kiisb. 2014. Entrepreneurship Education at University Level and Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions. Social and Behavioral Sciences 110: 658–668.

Kvietok, A. 2013. Psychological Profile of the Entrepreneur. http://www.psyx.cz/texty/psychologickyprofilpodnikatele.php. Accessed 24 Dec 2018.

Lüthje, C., and N. Franke. 2003. The ‘Making’ of an Entrepreneur: Testing a Model of Entrepreneurial Intent Among Engineering Students at MIT. R&D Management 33 (2): 135–147.

Lee, L., P.K. Wong, M.D. Foo, and A. Leung. 2011. Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Influence of Organizational and Individual Factors. Journal of Business Venturing 26: 124–136.

Lii, S.Y., and S.Y. Wong. 2008. The Antecedents of Overseas Adjustment and Commitment of Expatriates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 19: 296–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190701799861.

Luthans, F., J.B. Avey, B.J. Avolio, S.M. Norman, and G.M. Combs. 2006. Psychological Capital Development: Toward a Micro-Intervention. Journal of Organizational Behavior 27: 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.373.

Madichie, N. 2013. “Unintentional Demarketing ” in Higher Education. In Bradley, N., and Blythe, J. (Eds.) Demarketing (pp. 198–211). Routledge New York.

———. 2015. An Overview of Higher Education in the Arabian Gulf. International Journal of Business & Emerging Markets 7 (4): 326–335.

Madichie, N.O., and O. Fiberesima. 2019. Management Education Trends and Gaps–A Case Study of a Community Education Provision in London (UK). The International Journal of Management Education. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.04.004.

Madichie, N., and A. Gbadamosi. 2017. The Entrepreneurial University: An Exploration of “Value-Creation” in a Non-management Department. Journal of Management Development 36 (2): 196–216.

Madichie, N., and J. Kolo. 2013. An Exploratory Enquiry into the Internationalisation of Higher Education in the United Arab Emirates. The Marketing Review 13 (1): 83–99.

Madichie, N., K. Mpofu, and J. Kolo. 2017. Entrepreneurship Development in Africa: Insights from Nigeria’s and Zimbabwe’s Telecoms. In Entrepreneurship in Africa, 172–208. Leiden: Brill Publishing.

Maes, J., H. Leroy, and L. Sels. 2014. Gender Differences in Entrepreneurial Intentions: A TPB Multi-Group Analysis at Factor and Indicator Level. European Management Journal 32: 784–794.

Maresch, D., R. Harms, N. Kailer, and B. Wimmer-Wurm. 2016. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on the Entrepreneurial Intention of Students in Science and Engineering Versus Business Studies University Programs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 104: 172–179.

Messick, S. 1988. Validity. In Educational Measurement, ed. R.L. Linn, 3rd ed. New York: Macmillan.

Miranda, F.J., A. Chamorro-Mera, and S. Rubio. 2017. Academic Entrepreneurship in Spanish Universities: An Analysis of the Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intention. European Research on Management and Business Economics 23 (2): 113–122.

Murugesan, R., and R. Jayavelu. 2015. Testing the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Business, Engineering and Arts and Science Students Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Comparative Study. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 7 (3): 256–275.

Obschonka, M., M. Goethner, R.K. Silbereisen, and U. Cantner. 2012. Social Identity and the Transition to Entrepreneurship: The Role of Group Identification with Workplace Peers. Journal of Vocational Behavior 80 (1): 137–147.

Obschonka, M., R.K. Silbereisen, U. Cantner, and M. Goethner. 2015. Entrepreneurial Self-Identity: Predictors and Effects Within the Theory of Planned Behavior Framework. Journal of Business and Psychology 30 (4): 773–794.

Omerzel, G.D., and I. Kušce. 2013. The Influence of Personal and Environmental Factors on Entrepreneurs’ Performance. Kybernetes 42 (6): 906–927. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-08-2012-0024.

Paula, J., and A. Shrivatavab. 2016. Do Young Managers in a Developing Country Have Stronger Entrepreneurial Intentions? Theory and Debate. International Business Review 25: 1197–1210.

Peng, Z., G. Lu, and H. Kang. 2012. Entrepreneurial Intentions and Its Influencing Factors: A Survey of the University Students in Xi’an China. Creative Education 3 (Supplement): 95–100.

Rauch, A., and W. Hulsink. 2015. Putting Entrepreneurship Education Where the Intention to Act Lies: An Investigation into the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education on Entrepreneurial Behavior. Academy of Management Learning & Education 14 (2): 187–204.

Robson, P.J.A., H.M. Haugh, and B.A. Obeng. 2009. Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Ghana: Enterprising Africa. Small Business Economics 32: 331–350.

Rotter, J.B. 1954. Social Learning and Clinical Psychology. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Schlaegel, C., and M. Koenig. 2014. Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intent: A Meta–Analytic Test and Integration of Competing Models. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 38 (2): 291–332.

Schwarz, E.J., M.A. Wdowiak, D.A. Almer-Jarz, and R.J. Breitenecker. 2009. The Effects of Attitudes and Perceived Environment Conditions on Students’ Entrepreneurial Intent: An Austrian Perspective. Education+ Training 51 (4): 272–291.

Siegel, D. S., and P. Phan. 2005. Analyzing the Effectiveness of University Technology Transfer: Implications for Entrepreneurship Education. Advances in the Study of Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Economic Growth 16 (1): 1–38.

Taura, N. D., Bolat, E., & Madichie, N. (Eds.). 2019. Digital Entrepreneurship in Sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges, Opportunities and Prospects. Springer. Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04924-9

Teo, T., and C.B. Lee. 2010. Explaining the Intention to Use Technology Among Student Teachers. Campus-Wide Information Systems 27 (2): 60–67.

Thompson, E.R. 2009. Individual Entrepreneurial Intent: Construct Clarification and Development of an Internationally Reliable Metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33 (3): 669–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00321.x.

van Gelderen, M., M. Brand, M. van Praag, W. Bodewes, E. Poutsma, and A. van Gils. 2008. Explaining Entrepreneurial Intentions by means of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Career Development International 13 (6): 538–559.

Van Gelderen, M., T. Kautonenb, and M. Fink. 2015. From Entrepreneurial Intentions to Actions: Self-Control and Action-Related Doubt, Fear, and Aversion. Journal of Business Venturing 30: 655–673.

Yates, J.F., and E.R. Stone. 1992. The Risk Construct. In J. F. Yates (Ed.), Wiley Series in Human Performance and Cognition. Risk-Taking Behavior (p. 1–25).

Yıldırıma, N., Ö. Çakır, and O.B. Aşkun. 2016. Ready to Dare? A Case Study on the Entrepreneurial Intentions of Business and Engineering Students in Turkey. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 229: 277–288.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Madichie, N.O., Ibrahim, M., Adam, D.R., Ustarz, Y. (2020). Entrepreneurial Intentions Amongst African Students: A Case Study of the University of Education, Winneba, Ghana. In: Adesola, S., Datta, S. (eds) Entrepreneurial Universities. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48013-4_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48013-4_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-48012-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-48013-4

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)