Abstract

Theoretical and empirical research on business cycles became the dominant theme in economics in the interwar period. The foundation of the Harvard Committee in 1917 and the NBER in 1920 in the USA stimulated the foundation of similar research institutions in many European countries from the mid-1920s onwards, often co-financed by the Rockefeller Foundation. A special focus is on the Kiel Institute of World Economics which in the years 1926–1933 attracted many scholars who soon gained international reputation, so that Schumpeter in a letter to Keynes from October 1932 classified it as “the finest economic institute in the world.” A few months later, almost all leading economists were forced to emigrate, from Nazi Germany, continuing their academic career mainly in the UK and the USA.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

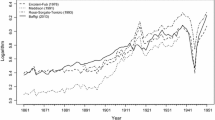

Theoretical and empirical research on business cycles became the dominant theme in economics in the interwar period. The foundation of the Harvard Committee on Economic Research in 1917 and the National Bureau of Economic Research NBER in 1920 in the United States stimulated the foundation of similar research institutions in many European countries, often co-financed by the Rockefeller Foundation. The Harvard Committee under its director Charles J. Bullock (1869–1941) soon hired Warren M. Persons (1878–1937) as its leading statistician who in 1919 was also appointed Professor of Economics at Harvard University and the first editor of the committee’s journal, The Review of Economic Statistics. Persons was instrumental in the creation of the famous Harvard Index of General Business Conditions, a three-curve barometer designed to forecast future outcomes by generalizing past experiences and as an indicator of turning points in the business cycle. Persons’s pioneering methods to eliminate seasonal and trend influences from time series data temporarily gave academic respectability to business cycle barometers in the 1920s during which the Harvard barometer disseminated quickly internationally.Footnote 1

Wesley C. Mitchell (1874–1948), who became the founding director of the NBER from 1920 to 1945, was already considered as the preeminent economist in business cycle research in the USA at the time of his appointment. Whereas in his earlier Business Cycles Mitchell (1913) had surveyed existing theories of economic fluctuations as well as the state of empirical knowledge about business cycles, and in contrast to later unfair attacks as “measurement without theory” acknowledged that theories determined which empirical facts should be examined more closely, in his subsequent Business Cycles: The Problem and Its Setting Mitchell (1927, 2) emphasized: “We must find out more about the facts before we can choose among the old explanations or improve upon them.” Although he pointed out that statistical data are of little use without illumination by theory, his priority to extensive description and measurement of real cycles, together with the empirical work at the NBER in his period to trace the timing of movements and of the amplitude of hundreds of variables within a cycle, across cycles and countries, without fully returning to address the question of causation, evoked some critique by more theoretically-minded economists.

From the mid-1920s onwards more systematic empirical research on business cycles became a major issue also in the German language areaFootnote 2 where new institutes were founded in Berlin and Vienna in 1925 and 1927, respectively. The Deutsches Institut für Konjunkturforschung, today’s DIW,Footnote 3 benefitted from the strong institutional cooperation with the Statistisches Reichsamt. Ernst Wagemann (1884–1956), the director in the first two decades was also the president of the Statistical Office of the Weimar Republic until he was dismissed from that position by the new Nazi-led government in March 1933. Ludwig von Mises was instrumental in the foundation of the Österreichisches Institut für Konjunkturforschung, today’s WIFO. Friedrich August Hayek (1899–1992) became the first director, succeeded in 1931, after his move to the London School of Economics, by Oskar Morgenstern (1902–1977) who stayed in that position until March 1938 when the Vienna Institute lost its independence after the “Anschluss” and became a branch office of the German Institute in Berlin.

In their empirical work both institutes were heavily influenced by the new methods of business cycle research, as they had been developed by Mitchell and the NBER and particularly by the Harvard University Committee on Economic Research. This was also noticed in the USA as, for example indicated by the two well-informed reports on the Austrian and German Institutes written by Carl Theodore Schmidt (1931a, b). The author gave particular attention to the extended elaboration of a series of “barometers” by Wagemann and his team, which took care of structural differences between the German and the US economies in their approach to the problem of economic forecasting.Footnote 4 This system of indices consisted of eight sectoral barometers covering production, employment, storage, foreign trade, business transactions, credit, comparative prices in security, money and commodity markets, and commodity prices.

Earlier on the Harvard index had also a stronger influence on the London and Cambridge Economic Service LCES which since its foundation in 1932 had a stronger cooperation with the Harvard Economic Service from which it also received substantial financial support until 1935.Footnote 5

In 1928 the Verein für Sozialpolitik, the Society for German-speaking economists, focused on the explanation of business cycles as the core topic for its annual meeting in Zurich. In his contribution on ‘Tasks and limits of the institutes for research on business cycles’ the young Morgenstern (1928a) distinguished two types of institutes, namely those with pronounced research intentions and those providing regular information services and forecasts for the subscribers of their publications. Whereas he classified the Kiel Institute of World Economics like the NBER in the former category, Morgenstern counted the institutes in Berlin and Vienna like the Harvard Economic Service to the latter. However, the separation between the two types was not an absolute one. This is demonstrated by the fact that Hayek as the first director of the Vienna institute exactly in those years made significant contributions to the (Austrian) theory of business cycles. In his keynote address to the 50th anniversary of the Austrian Institute Hayek (1977) confessed explicitly that business cycle theory always had interested him far more than regular reporting on the state of the economy and forecasting but that the latter was necessary to raise the money from business. Hayek had already the opportunity to study the new methods at Harvard and the NBER during his fourteen months stay in the USA in 1923–1924. However, in Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle Hayek ([1929] 1933, 27–28) entirely agreed with Löwe’s view that “empirical studies…cannot, in themselves, provide new insights into the causes or necessity of the Trade Cycle…and that to expect an immediate furtherance of theory from an increase in empirical insight is to misunderstand the logical relationship between theory and empirical research.”

Something similar can be said of the Berlin institute. Wagemann’s statistical approach is characterized by historical description and the construction of a series of indices, carefully avoiding (in contrast to Spiethoff) any simple general index of business conditions and a commitment to a clear formula of forecasting. No wonder that he is not even mentioned in Haberler’s great survey Prosperity and Depression (1937) which puts emphasis on the theoretical analysis of cyclical movements. But despite Wagemann’s aversion against theory it should not be overlooked that important theoretical contributions were made by members of the Berlin institute as, e.g. Arthur Hanau’s famous study on the cyclical fluctuations of supply and prices of pigs whose causes were explained in the form of the cobweb theorem (Hanau 1927), and thus contributed to the surmounting of the static by a more dynamic analysis of the cycle.

The Berlin “institute was perhaps the most important single influence in spreading knowledge of modern statistical methods (as then understood). Its methodological work is therefore of historical importance” (Schumpeter 1954, 1155). Wagemann, no doubt, was a capable organizer of economic research as was Bernhard Harms (1876–1939), “one of the most efficient organizers of research who ever lived” (ibid.), who had founded the Institute of World Economics at the University of Kiel in February 1914.Footnote 6 Until the mid-1920s the institute had collected masses of statistical material on international trade and sea traffic and was engaged in building up an impressive library but did not enter into deeper theoretical analysis. This changed completely when in April 1926 Harms hired Adolf Löwe (1893–1995, since September 1939 Adolph Lowe) to build up a new department for research in statistical economics and trade cycles (Abteilung für Statistische Weltwirtschaftskunde und Internationale Konjunkturforschung ASTWIK) which soon acquired international reputation.

Although Löwe had closely cooperated with Wagemann since he had been appointed head of the international department in the Statistical Office in 1924, and in particular in the foundation process of the Berlin Institute,Footnote 7 the research work at Kiel was remarkably different from the work in Berlin. It transcended beyond statistical economics and trade cycle analysis, addressing also long-run growth, structural change and employment consequences of technological change, and had a much stronger theoretical flavour. Like Morgenstern (1928b) Löwe was skeptical about economic forecasting. These differences contributed to an increasing alienation between Löwe and Wagemann who had established a new department on the statistics of business cycles at the Statistisches Reichsamt in 1924 which gave enormous support to the empirical work at the Berlin institute. Nevertheless Wagemann, who admired Mitchell’s synthesis of theoretical, statistical and historical work on business cycles,Footnote 8 defended himself against the reduction of the efforts of the institutes to pure empirical-statistical work. Löwe, on the other hand, recognized that the Berlin institute with its much greater man power had comparative advantages on the empirical side and concentrated his own efforts more on the theoretical side, as best reflected in his methodologically oriented Kiel habilitation thesis with the Kantian-inspired question “How is business-cycle theory possible at all?” (Löwe 1926), in which he placed the problem of (in)compatibility of the analysis of cyclical fluctuations within the dominant equilibrium approach in economics into the centre. He also criticized Wagemann when he pointed out: “To expect an immediate furtherance of theory from an increase in empirical insights is to misunderstand the logical relationship between theory and empirical research” (Löwe [1926, 166] 1997, 246). Löwe’s criticism was shared by the Austrians Mises, Morgenstern and Hayek who “recognized that the use of statistics can never consist in a deepening of our theoretical insights” (Hayek [1929] 1933, 32). The controversy, which sometimes contained elements of a new Methodenstreit (dispute on method), reflected a still existing gap between theoretical and empirical work among many contemporary researchers on business cycles in the interwar period.

In the following I will focus on the Kiel group which spread out internationally after the Nazis’ rise to power in 1933. An important role in the process was played by the Rockefeller Foundation giving financial support which became particularly important during the years of the Great Depression.

2 The Role of the Rockefeller Foundation

“The Kiel Institute constitutes one of the bright spots in German economics,” John Van Sickle, the assistant director of the social science division of the Rockefeller Foundation RF wrote to the director Edmund Day in his European office in Paris on August 2, 1932.Footnote 9 A year before he had already noticed in his diary that Harms “had gathered around him some of the best young economists in Germany” (Craver 1986, 216). Tracy Kittredge, Van Sickle’s successor considered the Kiel Institute even as “a Mecca for research workers interested in international economic problems”.Footnote 10 Beardsley Ruml, who had been appointed director of the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial in 1922, was already very much impressed with the facilities, particularly the library, when he first visited the Kiel Institute in 1925. In the same year the University of Kiel, at the initiative of Harms, awarded an honorary doctoral degree to John Maynard Keynes and Herbert Hoover, then Minister of Trade and later US President, on 10 June.

“[T]he work being done in Kiel was the kind of work done by the kind of economists, that directors of the [RF] foundation most wished to support and encourage,” Earlene Craver (1986, 216) notes in her excellent survey of the activities of the RF in Europe in the interwar period. This holds in particular for the ASTWIK whose members had acquired a high national and international scientific reputation in the last years of the Weimar Republic. However, it was not before spring 1931 that the RF decided to support the scientific programme with an annual amount of $10,000 over a period of three years.Footnote 11 Before the Kiel Institute had only received library grants of $1600 for 1925 and $10,000 for 1926–1927 to buy foreign books and journals which was a great help for the building up of its impressive library. Until today the library is a great worldwide attractor for economists to spend research periods at the Kiel Institute. The long-time director Wilhelm Gülich (1926–1960), who had established the famous Kiel catalogue, himself had visited the USA with a RF fellowship, and in 1926 had been considered a serious candidate for directorship of the library of the League of Nations in Geneva which also was financially supported by the RF.

Although $10,000 in 1926 amounted to almost 10% of the overall budget of the Kiel Institute, it was only a small sum compared to the $1,245,000 which the LSE alone received between 1924 and 1928. In that period emphasis of the RF was on institutional grants to foster strong centres of interdisciplinary research, preferably applying modern methods of empirical research such as the NBER. Major beneficiaries in Europe were also three institutions in Geneva, Stockholm and Copenhagen (Craver 1986, 208). German and Austrian economists mainly benefitted from the fellowship programme of the RF as, for example Gottfried Haberler, Ludwig Mises and Oskar Morgenstern. During his stay in the US the latter also developed a closer personal friendship with Andreas Predöhl (1893–1974) who later became director of the Kiel Institute in the Nazi period from 1934 to 1945. Predöhl, whose main area was location theory,Footnote 12 was one of the two from Kiel out of thirteen German fellows in economics until 1928.

As well explained by Craver (1986, 210ff.), after the outbreak of the Great Depression with the crash on Wall Street in October 1929 and under the new directorship of Edmund E. Day in the social sciences, the RF changed its funding policy in favour of institutes and projects aiming to find causes of cyclical fluctuations. “Economic stabilization became one of the three principal topics of interest of the social science division during Day’s administration” (212). A major beneficiary was the Institut scientifique de recherches économiques et sociales IRES founded by Charles Rist (1874–1955) in Paris in October 1933 with a seven years grant of $350,000. From today’s perspective the list of recipients documents an excellent knowledge and assessment of the quality of the research work being done at the various European institutes for research on business cycles. Besides the institutes in Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Kiel and the LSE also the one at the University of Oslo (Ragnar Frisch), the Dutch in Rotterdam (Peter Lieftinck and Jan Tinbergen), the Belgian in Louvain (Léon Dupriez), the Swedish in Stockholm (Bertil Ohlin) the Bulgarian in Sofia (Oskar Anderson), the Hungarian in Budapest (Stephan Varga), the Polish in Cracow (Adam Heydel) and the Roumanian in Bucharest (Dimitrie Gusti).Footnote 13 Anderson, Dupriez, Morgenstern, Ohlin, Rist and Tinbergen also attended the meetings of the Committee of Experts in Geneva from 29 June to 2 July 1936 to discuss Part II “Synthetic exposition relating to the nature and causes of business cycles” of Haberler’s investigation Prosperity and Depression, carried out on behalf of the League of Nations and financed by a grant from the RF.Footnote 14 The RF was also a key driving force and sponsor of the network of international cooperation between the national institutes which developed in the 1930s but collapsed with the outbreak of WWII. In Germany other recipients were also Arthur Spiethoff in Bonn and the Institute for Social and State Sciences at the University of Heidelberg with the two directors Alfred Weber (the younger brother of Max) and Emil Lederer, who moved to Berlin in 1931, and after his emigration in 1933 became the first Dean of the “University in Exile” at the New School for Social Research in New York. The Kiel Institute, however, was favoured by the RF since due to the broad team composition and high quality of its research staff it was least likely to succumb to the tendency of German institutes that with the death, retirement or moving away of the director the Institute vegetates or disappears, as Kittredge reflected in his report.Footnote 15

3 The Kiel Institute of World Economics: Excellence for Seven Years

The years of high theory started at the Kiel Institute in April 1926 and lasted exactly for only seven years. Within a short period of time Löwe was able to hire a top-calibre crew of young and innovative researchers who developed a great team spirit and soon won (inter)national reputation. The group of highly qualified researchers included Gerhard Colm (1897–1968), an expert on public finance,Footnote 16 who in April 1927 was recruited by Lowe from the Statistical Office in Berlin where he had developed an internationally comparative financial statistics which was important for the reparation problem. Colm was a pioneer in national income and wealth accounting. After Löwe was appointed Full Professor at the University, Colm succeeded him in March 1930 as head of the business cycle research department with Neisser as his deputy. Hans Neisser (1895–1975) also came in 1927 from Berlin, where he had worked as a researcher in the Enquête Aussschuss (State Committee of Industrial Investigations), to Kiel. He established himself as a leading monetary theorist with his habilitation thesis The Purchasing Power of Money but also contributed to general equilibrium theory, the machinery problem and other theoretically difficult and practically relevant topics. Neisser was highly appreciated by Keynes and Hayek alike and described by Schumpeter (2000, 247) “as a brilliant scientist”. Löwe, Colm and Neisser formed the core of the Astwik group that later came to be known as the “Kiel School ”.Footnote 17 The team included other excellent young economists such as Fritz Burchardt (1902–1958) or Alfred Kähler (1900–1981). The outstanding quality of the Kiel group is also indicated by the fact that two young émigrés from Russia, who later became world-famous economists joined the team for some years: Wassily Leontief (1905–1999) from April 1927 to April 1931, only interrupted by a twelve-months stay in China, and Jacob Marschak (1898–1977), “probably the most gifted scientific economist of the exact quantitative type now in Germany” (Schumpeter 2000, 247), from 1928 to 1930.

Löwe had already examined the existing body of theoretical and empirical work on business cycles in his survey “The present state of research on business cycles in Germany” (Löwe 1925) before he wrote his methodologically oriented Kiel habilitation thesis with the Kantian-inspired question “How is business-cycle theory possible at all?” (Löwe [1926] 1997), in which he raised the problem of incompatibility of business cycle theory within the dominant equilibrium approach in economics. Löwe clearly was inspired by the fundamental distinction between statics and dynamics in Schumpeter’s theoretical system and Schumpeter’s view that a Walrasian system of general economic equilibrium was inappropriate for the analysis of business cycles, when he made his claim for a new dynamic theory “in which the polarity of upswing and crisis arises analytically from the conditions of the system just as the undisturbed adjustment derives from the conditions of the static system. Those who wish to solve the business cycle problem must sacrifice the static system. Those who adhere to the static system must abandon the business cycle problem” (Löwe [1926] 1997, 267).

Löwe’s influential role in the subsequent debate can best be seen by looking into Hayek’s Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle ([1929] 1933) which is characterized by the challenge arising from Löwe’s attack which poses a major issue for Hayek. Whereas he agrees with Löwe’s identification of cyclical fluctuations in equilibrium theory as the crucial problem of business cycle theory; however, Hayek seriously disagrees in the conclusion drawn. Hayek’s writings on monetary theory and business cycle theory in the interwar period are firmly based on an equilibrium approach. He therefore also considered it essential to start the explanation of cyclical fluctuations from an assumption of an economy in equilibrium with full utilization of resources.

The contemporary theoretical debate in the German language area was dominated by the economists from Kiel and Vienna. This is also indicated by a second controversy which extends into modern times. Whereas Hayek and Löwe agreed that business cycle theory must present an endogenous factor causing fluctuations, they differed in the decisive dynamic impulse identified. In contrast to Löwe, who in line with Wicksell and Schumpeter emphasized technical progress as the fundamental causal factor, Hayek, in agreement with Mises, considered cyclical fluctuations to be caused by monetary factors. He later had a life-long controversy with Hicks who, as Löwe, considered technological changes as more fundamental. Löwe’s main intention in his contribution “On the Influence of Monetary Factors on the Business Cycle” to the 1928 Zurich meeting of the Verein für Sozialpolitik, which he had already presented earlier to the Austrian Economics Society (Nationalökonomische Gesellschaft) in Vienna, was to show that monetary factors are neither necessary nor sufficient for the explanation of business cycles. Löwe’s analysis was supported by the parallel study on the evolution of monetary theory by his closest research collaborator Burchardt (1928), which was distributed to the participants of the Zurich meeting, where the issue of monetary versus non-monetary business cycle theories had been chosen as a special theme. Recognizing that monetary influences manifested themselves primarily through changes in the price level, Burchardt concluded that monetary factors alone could not explain cyclical fluctuations. Non-monetary factors, in particular technical progress, play a central role. Thus Burchardt pointed out that in Wicksell’s theory the equilibrium of an economy is disturbed by technical progress which causes the natural rate to rise above the market rate of interest.

Hayek appreciated Burchardt’s essay as “very valuable in its historical part” (Hayek 1929, 57), but he criticized Löwe and Burchardt for resting their essential point “exclusively on the idea that only general price changes can be recognized as monetary effects” (Hayek [1929] 1933, 123). Therefore, in his Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle, which is an expanded version of his own contribution to the Zurich meeting, he emphasizes that monetary theory has by no means accomplished its task when it has explained the absolute level of prices. Hayek argues against simplified monetary theories of the business cycle which focus exclusively on the relation between changes in the quantity of money and changes in the general level of prices. A far more important task is to explain changes in the structure of relative prices caused by monetary injections and the consequential disproportionalities in the structure of production which arise because the price system communicates false information about consumer preferences and resource availabilities. Misallocation of resources due to credit expansion could even occur despite price level stability.

While in Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle Hayek’s focus is on the monetary factors causing the cycle, in his subsequent Prices and Production based on his LSE lectures (Hayek 1931), emphasis is on the real structure of production. Here we come to a third important point of agreement and disagreement between Hayek and the members of the Kiel School.Footnote 18 Both identified changes in the structure of production as a key characteristic of cyclical fluctuations which has to be addressed by business cycle theory . In the famous triangles of Prices and Production Hayek applies Böhm-Bawerk’s Austrian representation of the structure of production in which a sequence of original inputs of labour is transformed into a single output of consumption goods. In this unidirectional way of representing the production process only intermediate capital goods but not fixed capital goods or circularity exist as in a sectoral input–output system of a Leontief-Sraffa type. Burchardt and Löwe, on the contrary, preferred a horizontal or sectoral approach as in Marx’s schemes of reproduction. In two important essays Burchardt (1931–1932) provided the first synthesis of the schemes of the stationary circular flow in Böhm-Bawerk and Marx, i.e. of the vertical and the horizontal approach.Footnote 19

With the beginning of the new academic year in October 1931 Burchardt moved with Löwe to Frankfurt where the Goethe University had developed into a leading reform university in the social sciences during the Weimar Republic. Fifteen months later he submitted his habilitation thesis on Quesnay’s Tableau Économique as a foundation of business cycle theory. However, due to the Nazis’ rise to power shortly afterwards the habilitation process remained unfinished. Whereas at Frankfurt Löwe succeeded the Austrian Carl Grünberg (1861–1940) who became a victim of the Gestapo, the Christian Albrechts University in Kiel offered Löwe’s former chair to Hans Mayer (1879–1955) who had succeeded Friedrich von Wieser at the University of Vienna in 1923 on the chair formerly held by Carl Menger from 1879 to 1903. Mayer who also edited the Vienna-based Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie had substituted Löwe’s professorship since the Winter semester 1931/32 and already accepted a full professorship beginning with the Summer semester in April 1933. However, after some Nazi raids in the Institute of World Economics he revoked on April 21 anticipating his dismissal and returned to Vienna (Take 2019, 73–74), where he behaved in a more opportunistic way after the “Anschluss” in March 1938 and remained in all his positions during the Nazi period.

4 (In)Voluntary Internationalization

On October 22, 1932, shortly after his move from Bonn to Harvard, Schumpeter wrote in a letter to Keynes: “Harms…has built up the finest economic institute in the world” (Schumpeter 2000, 224). Less than six months later, on 7 April 1933, the Nazi government launched the Restoration of Civil Service Act which enabled them to dismiss civil servants either for racial and/or political reasons. Within a short time, almost 3000 scholars were removed from their academic positions, about 85% for their “non-Aryan” descent and 15% as political enemies. Starting on April 1, the day of organized boycott against Jewish shops, five brutal raids took place in the Kiel Institute. At the end of the month six Astwik members, with Colm and Neisser on top, and four from a related department were kicked out of the Institute.Footnote 20 Over the summer the director Harms (neither Jewish nor a social democrat but for having promoted too many of them) was attacked, thrown out and replaced by a young Nazi economist Jens Jessen who came from Göttingen. When in summer 1933 the RF sent Alva and Gunnar Myrdal to Kiel for assessing the situation, they delivered a precise and well-informed ReportFootnote 21 on the new situation. They pointed out that all talented economists were thrown out, that there remained only “a somewhat unimportant rump faculty,” and considered Jessen as a fanatic Nazi who “is not a very prominent scholar”.Footnote 22 It took until 1936 that the RF under its new president Raymond Fosdick finally stopped the (in) direct financial support of the Kiel institute.

On the other hand, the RF was a most important source of financial support for the émigré scholars from the beginning. For example, they co-financed the salary of Hans Neisser over several years during his time as professor at the Wharton School of Finance of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.Footnote 23

On April 19, only twelve days after the Restoration of Civil Service Act, Schumpeter wrote a letter from Harvard to Wesley C. Mitchell asking for support of outstanding Hebrew colleagues in Germany (Schumpeter 2000, 246–48). “The men listed may all of them be described as more than competent.” The ranking list of Schumpeter contained Gustav Stolper (his friend from Vienna whose son Wolfgang had moved with him as a PhD student from Bonn to Harvard in September 1932), Jacob Marschak, Hans Neisser, the sociologist Karl Mannheim, Emil Lederer, Adolph Löwe, Gerhard Colm, Karl Pribram and Eugen Altschul, i.e. four economists who had spent some years at the Kiel Institute between 1926 and 1933. Leontief was appointed Assistant Professor at Harvard at the same time when Schumpeter arrived. He had moved from Kiel to the U.S. already in the preceding year and spent the time at the NBER in New York. Eugen Altschul, the director of the Frankfurt Society for Research on Business Cycles (Frankfurter Gesellschaft für Konjunkturforschung) from its foundation in June 1926 to April 1933, who had edited the German translation of Mitchell’s Business Cycles, also got a position at the NBER from December 1933 to 1939. The important publication series which he had initiated at Frankfurt started with Oskar Anderson’s (1929) critical evaluation of the Harvard methods to decompose statistical time series. Anderson, an excellent statistician maintained closer contacts with the Vienna Institute in the 1930s, as, for example indicated by Morgenstern’s lecture “Organisation, achievements and further tasks of business cycle research” delivered in Sofia on 2 April 1935 (Morgenstern 1935). Due to Predöhl’s initiative Oskar Anderson (1887–1960) came to Kiel in May 1942 as the director of a new department on Eastern research at the Institute of World Economics (Take 2019). In 1947 Anderson was appointed Professor at the University of Munich.

Jacob Marschak was thrown out of his position in Heidelberg in April 1933. Immediately afterwards he suggested to the RF that the dismissed scholars from Kiel and Heidelberg should form a kind of “University in Exile” in Geneva with the redirected funds which the RF had donated to the German institutes (Take 2017, 284–86). After his proposal was rejected Marschak emigrated to Great Britain where he became Chichele Lecturer in economics at All Souls in Oxford in fall 1933. In 1935 Marschak was appointed Reader in Statistics and the founding Director of the Oxford Institute of Statistics OIS which received substantial financial support from the RF. In September 1936 the OIS hosted the famous conference of the Econometric Society at which John Hicks presented his “Mr. Keynes and the ‘Classics’” formalizing Keynes’ General Theory, which marked the beginning of the IS-LM model and the birth of the neoclassical synthesis. During the few years of Marschak’s directorship the OIS established itself as a leading international centre for empirical research in economics, advancing modern statistical and econometric techniques.

During the Nazi period the OIS hosted many refuge scholars from Central Europe. Among them was (since his emigration to England in 1935 Frank) Burchardt who built up the Institute’s Bulletin. In 1944 he edited the famous The Economics of Full Employment, a collection of six studies in applied economics (Burchardt 1944). With Burchardt, Michal Kalecki, E. F. Schumacher, Thomas Balogh and Kurt Mandelbaum five of the six authors were émigrés. In 1949 Burchardt became director of the OIS.

Due to their high academic qualification and their open-mindedness the former Astwik members were much better connected with the international community than most other contemporary German economists and social scientists. Particularly former RF fellows or RF-funded researchers had easier access to financial support from the Deposed Scholars Program. Marschak is an outstanding case. In December 1938 he embarked for the USA with a one-year fellowship from the RF. After the outbreak of WWII he remained in America, succeeding Gerhard Colm on his chair at the New School after the latter’s joining the Roosevelt administration.Footnote 24 Colm like Alfred Kähler, who, while at Kiel, had written an important study The theory of the displacement of workers by machinery (Kähler 1933) in which he analyzes the problem of technological unemployment on the basis of an early static input–output model, had been a member of the “Mayflower” generation of professors of the “University in Exile” in 1933.Footnote 25 In January 1943 Marschak was appointed Professor of Economics at the University of Chicago and Director of the Cowles Commission for Research in Economics. Under Marschak’s directorship (1943–1948) the Cowles Commission soon became the world centre of the econometric revolution in economics.

At the New School Marschak had met again his lifelong friend Adolph Lowe who came over from Manchester to New York in summer 1940. Lowe and Marschak were highly appreciated by the RF as “A-1, both scientifically and from the point of view of character”,Footnote 26 and regularly consulted by the Academic Assistance Council/Society for the Protection of Science and Learning to assess the qualification of persecuted social scientists who were looking for help.Footnote 27 The most prominent PhD student of Marschak and Lowe was Franco Modigliani (1918–2003),Footnote 28 himself an émigré economist from fascist Italy who had arrived in New York four days before the outbreak of WWII, and later received the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel in 1985 for his work in macroeconomic theory. On the Modigliani homepage of the Nobel Prize Committee we read:

I had the great luck of being awarded a free tuition fellowship by the Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science of the New School for Social Research…as I was discovering my passion for economics, thanks also to excellent teachers, including Adolph Lowe and above all Jacob Marschak to whom I owe a debt of gratitude beyond words. (Modigliani Homepage Nobel Prize Committee 1985, 1–2)

As a lecturer in econometrics and research associate of the Institute of World Affairs at the New School Modigliani cooperated closely with Neisser (who had come from Philadelphia to New York in 1943) in the years 1944–1948 which amounted in their joint publication National Incomes and International Trade: A Quantitative Analysis (Neisser and Modigliani 1953). The book contained the most comprehensive econometric investigation of its era, elaborating and extending earlier work on foreign trade, business cycles and structural change in the global economy. Neisser had already started similar work in Kiel and continued in Philadelphia (Trautwein 2017, 942–45). The Institute of World Affairs which officially was opened in November 1943 with enormous financial support from Doris Duke but was already engaged in major research projects since America’s entering the war in 1941, many of them financed by RF, was the research arm of the New School (Friedlander 2019, 149–51). At its creation the role model was the Kiel Institute of World Economics, an impression strengthened by the fact that Lowe was appointed its Director of Research who played a similar role as in Kiel 1926–1930.

Some of the scholars dismissed in Kiel temporarily or permanently remained in Europe. Rudolf Freund (1901–1955) who worked at the Kiel Institute from 1926–1929 and from 1931–1933 as the expert for international trade and cyclical fluctuations in the agricultural sector stayed as researcher at the Stockholm School of Economics until 1939 when he was appointed professor at the University of Virginia. He was strongly supported by Gunnar Myrdal as was the sociologist Svend Riemer (1905–1977) who moved further to the U.S. in 1938 where he ended up as professor at UCLA. The employment of Freund and Riemer was financed by the RF and the Swedish Academic Assistance Council. Konrad Zweig (1904–1980) who had worked in the Astwik as a specialist for the statistics of international capital movements was among the many émigré scholars who could not pursue an academic career, despite high appreciation by Hayek, Löwe and Colm alike. He earned his living by working for Lyons, a food manufacturer in London. On the other side, the high quality of the work at Kiel is illuminated also by the career of Hal C. (Hermann Christian) Hillmann (1910–1990), who was the student assistant of Colm and chairman of the socialdemocratic student group at the University of Kiel. After several months in a concentration camp he could escape to Britain in January 1934. During the war he worked as a research officer and expert on the German war economy in the Royal Institute of International Affairs at Balliol College in Oxford.Footnote 29

An interesting case is John H. (Jean) Herberts who was born in Bremen in 1905 and whose traces got lost in Paris at the beginning of WWII. He was dismissed in Kiel in August 1933 for his “non-Aryan” descent. In the same month he emigrated to France where he got a position at the IRES in Paris in the following May. Interestingly, Herberts who, for example represented the Institute at the fifth international conference of the research institutes on business cycles, which was organized by Oskar Morgenstern in Vienna in July 1936,Footnote 30 was able to publish an informative article on the Paris institute in the Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv (45, 1937), the journal of the Kiel Institute which had thrown him out four years before. In those years enormous efforts were made to establish a permanent secretariat for the international network of the business cycles research institutes. The chairman Rist and the majority favoured Geneva as the location, which made sense because of the League of Nations, ILO and a lot of statistical material available there, and Morgenstern as the half-time Secretary. Both proposals were heavily opposed by Dupriez who considered Geneva as a place too much dominated by Protestants and was against Morgenstern due to his double role and burden as the president of the Vienna institute. In May 1937 Dupriez also visited the Institute of World Economics in Kiel and the Berlin Institute directed by Wagemann, who two years earlier had opposed Van Sickle’s proposal to appoint Loveday as the coordinator of the conference of the business cycles research institutes. In his report to the RF of 9 July Dupriez, like so many before and after him, praised the excellent library of the Kiel Institute but understandably was critical of the overall intellectual climate in Germany. No doubt, in the years 1933–1938 the Vienna Institute under Morgenstern’s direction had the pole position in the German language area. Nevertheless it was shortly before the Anschluss in March 1938 that the coordinating secretariat was located at the Rist institute in Paris and Robert Marjolin, himself a former RF fellow, was appointed Secretary. Shortly afterwards the political events caused an end to the promising international cooperation of the leading research institutes on business cycles.

The spirit of international cooperation among the participating economists, however, was not dead. A characteristic example is Marschak’s article “Peace Economics,” written within the New School’s Peace Studies Project in summer 1940 when Nazism after the defeat of France was at its peak. Here the author attributes the rise of National Socialism in Germany, and the success of radical political parties in other countries, to the failure of the existing democracies to solve the mass unemployment problem. “No peace will be a lasting one with the economic problem unsolved” (Marschak 1940, 283). Marschak points out three postulates for peace economics, namely that there should be no idle resources, resources should be allocated in an optimal way and developed in the best possible proportions. “The first postulate is […] equivalent to a requirement that booms and depressions be mitigated” (286). The first postulate is the most important one where “the necessity to remove depression, comes in: idle resources must be put to work” (287). Time and again the author emphasizes that depression “has produced more unrest, and has been responsible for more dangers to the peace of the world than any difficulties in reconstructing equipment damaged by war or any delay in the development of new resources” (289).

Against superprotectionism, sauve qui peut or “beggar my neighbor” policies which would cause retaliation and thereby a downward spiral, Marschak favours policies that will safeguard internal equilibrium and external equilibrium simultaneously which “is the real problem of economic policy in a world where idle resources are possible” (292). Unilateral policies of austerity or devaluation are doomed to fail. However, internationally coordinated public works programmes between the major countries eliminating fears of balance of payments problems are a precondition for a successful antidepression policy and thereby a major contribution to peace. Such a “pari passu policy against booms and depressions” should also include “a joint development of the so-called backward countries” (291). Marschak’s position as a genuine internationalist is also reflected in his final plea for a setting up of institutions as instruments for a peaceful economic order such as the International Equalization Fund, an International Public Works Board or a Bank for International Credit, preshadowing the creation of institutions for international economic cooperation at Bretton Woods four years later.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

For an informative study on the beginnings of systematic empirical research on business cycles in Germany in the critical phase between 1925 and 1933 see Kulla (1996).

- 3.

On the history of the Berlin Institute see Krengel (1986).

- 4.

The business-cycle barometer constructed by Arthur Spiethoff (1873–1957) in the mid-1920s, on the other hand, almost exclusively concentrated on the consumption of pig iron. Most leading international researchers contributed to the Festschrift for Spiethoff on The State and the Near Future of Business Cycle Research (Clausing 1933).

- 5.

For a detailed analysis of the history and contributions of the LCES, in whose activities leading economists on both sides were involved, see Cord (2017).

- 6.

The original name was Institut für Seeverkehr und Weltwirtschaft.

- 7.

See also Lowe’s reflections on business cycles research in Weimar Germany (Löwe 1989).

- 8.

Mitchell wrote a Preface to the English translation of Wagemann’s Konjunkturlehre (1928).

- 9.

RF Archive Center RAC, Record Group 1.1, series 7175, box 20, folder 180.

- 10.

RAC, ibid., folder 186.

- 11.

See Take (2018, 258) who has carefully documented the support of the Kiel Institute by the RF in the period 1925–1950.

- 12.

See, for example, Predöhl (1928) as a main publication from this period.

- 13.

The Russian Konjuncture institute in Moscow which had been founded in 1920 was already closed down in 1928 and its director Nikolay Kondratieff was sent to Siberia where he was murdered in 1938 at the order of Stalin.

- 14.

See Boianovsky and Trautwein (2006, 62–76) for further details.

- 15.

- 16.

See his Kiel habilitation thesis Economic Theory of Government Expenditures (Colm 1927).

- 17.

See Hagemann (1997).

- 18.

For a more detailed discussion see Hagemann (1994).

- 19.

For its significance for modern theories of structural change see the contributions in Baranzini and Scazzieri (1990).

- 20.

For greater details see Take (2017, 2019).

- 21.

Alva and Gunnar Myrdal, Report to Dr. John Van Sickle in Paris, 20 July 1933, Stockholm, RFA, RG 1.1, series 717S, box 20, folder 1933.

- 22.

Jessen was replaced as the director by Predöhl in the following year and executed in November 1944.

- 23.

On Neisser see also Trautwein (2017).

- 24.

- 25.

On Colm see also Milberg (2017).

- 26.

John van Sickle, Paris, to the headquarter in New York, 10 May 1933; RAC, RG1.1, 200/109/539.

- 27.

The AAC was founded in May 1933 (renamed into SPSL in 1936) at the initiative of William Beveridge to help “University teachers and investigators of whatever country who, on grounds of religion, political opinion or race, are unable to carry their work in their own country”.

- 28.

See Hagemann (2017).

- 29.

For greater details on Freund, Hillmann, Zweig, Herberts et al. see the contributions in Hagemann and Krohn (1999).

- 30.

Among other participants were Alvin Hansen, Haberler, Tinbergen, Ohlin, Anderson, Mises, Schwartz (LCES), Dupriez, Pedersen (Copenhagen), Lipinski, Varga, Kittredge (RF) and also some Japanese.

References

Anderson, Oskar. 1929. Zur Problematik der empirisch-statistischen Konjunkturforschung. Bonn: Verlag Kurt Schroeder.

Baranzini, Mauro, and Roberto Scazzieri, eds. 1990. The Economic Theory of Structure and Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boianovsky, Mauro, and Hans-Michael Trautwein. 2006. “Haberler, the League of Nations, and the Quest for Consensus in Business Cycle Theory in the 1930s.” History of Political Economy 38 (1): 45–89.

Burchardt, Fritz A. 1928. “Entwicklungsgeschichte der monetären Konjunkturtheorie.” Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 28: 78–143.

———. 1931–32. “Die Schemata des stationären Kreislaufs bei Böhm-Bawerk und Marx.” Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 34: 525–564 and 35: 116–176.

———, ed. 1944. The Economics of Full Employment. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Clausing, Gustav, ed. 1933. Der Stand und die nächste Zukunft der Konjunkturforschung. Festschrift für Arthur Spiethoff. Munich: Duncker & Humblot.

Colm, Gerhard. 1927. Volkswirtschaftliche Theorie der Staatsausgaben. Tübingen: Mohr.

Cord, Robert A. 2017. “The London and Cambridge Economic Service: history and contributions.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 41: 307–26.

Craver, Earlene. 1986. “Patronage and the Directions of Research in Economics: The Rockefeller Foundation in Europe, 1924–1938.” Minerva 24: 205–22.

Friedlander, Judith. 2019. A Light in Dark Times: The New School for Social Research and Its University in Exile. New York: Columbia University Press.

Haberler, Gottfried. 1937. Prosperity and Depression: A Theoretical Analysis of Cyclical Movements. Geneva: League of Nations.

Hagemann, Harald. 1994. “Hayek and the Kiel School: Some Reflections on the German Debate on Business Cycles in the Late 1920s and Early 1930s.” In Money and Business Cycles: The Economics of F. A. Hayek, Vol. 1, edited by Marina Colonna and Harald Hagemann, 101–20. Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

———. 1997. “Zerstörung eines innovativen Forschungszentrums und Emigrationsgewinn. Zur Rolle der ‘Kieler Schule’ 1926–1933 und ihrer Wirkung im Exil.” In Zur deutschsprachigen wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Emigration nach 1933, edited by Harald Hagemann, 293–341. Marburg: Metropolis.

———. 2007. “German-Speaking Economists in British Exile.” Banca Nazionale del Lavoro Quarterly Review LX (242): 323–63.

———. 2011. “European Émigrés and the ‘Americanization’ of Economics.” The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 18 (5): 643–71.

———. 2017. “Franco Modigliani as ‘American’ Keynesian: How the University in Exile Economists Influenced Economics.” Social Research 84 (4): 955–85.

Hagemann, Harald, and Claus-Dieter Krohn, eds. 1999. Biographisches Handbuch der deutschsprachigen wirtschaftswissenschaftlichen Emigration nach 1933. Munich: K.G. Saur.

Hanau, Arthur. 1927. Die Prognose der Schweinepreise. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Hayek, Friedrich A. [1929] 1933. Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle. London: J. Cape.

———. [1931] 1935. Prices and Production. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

———. 1977. “Zur Gründung des Instituts.” In Österreichisches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung, 50 Jahre, 13–19. Vienna: WIFO.

Kähler, Alfred. 1933. Die Theorie der Arbeiterfreisetzung durch die Maschine. Eine gesamtwirtschaftliche Abhandlung des modernen Technisierungsprozesses. Greifwald: Julius Abel.

Krengel, Rolf. 1986. Das deutsche Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung (Institut für Konjunkturforschung), 1925–1979. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Kulla, Bernd. 1996. Die Anfänge der empirischen Konjunkturforschung in Deutschland 1925–1933. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Lenel, Laetitia. 2018. “Futurama. Business Forecasting and the Dynamics of Capitalism in the Interwar Period.” Working Paper No. 3 of the DFG Priority Programme 1859 Experience and Expectations, Historical Foundations of Economic Behaviour. Berlin: Humboldt University.

Löwe, Adolph. 1925. “Der gegenwärtige Stand der Konjunkturforschung in Deutschland” In Die Wirtschaftswissenschaft nach dem Kriege. Festschrift für Lujo Brentano zum 80. Geburtstag, edited by Julius Bonn and Melchior Palyi, Vol. 2, 329–77. Munich and Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.

———. 1926. “Wie ist Konjunkturtheorie überhaupt möglich?” Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 24: 165–97; English translation as “How Is Business-Cycle Theory Possible at All?” Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 8: 245–76, 1997.

———. 1928. “Über den Einfluß monetärer Faktoren auf den Konjunkturzyklus.” English translation “On the Influence of Monetary Factors on the Business Cycle.” In Business Cycle Theory. Selected Texts 1860–1939, Vol. III: Monetary Theories of the Business Cycle, edited by Harald Hagemann, 199–211. London: Pickering & Chatto, 2002.

———. 1989. “Konjunkturtheorie in Deutschland in den Zwanziger Jahren.” In Studien zur Entwicklung der ökonomischen Theorie, edited by Bertram Schefold, VIII, 75–86. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot.

Marschak, Jacob. 1940. “Peace Economics.” Social Research 7 (3): 280–98.

Milberg, William. 2017. “Gerhard Colm and the Americanization of Weimar Economic Thought.” Social Research 84 (4): 989–1019.

Mitchell, Wesley C. 1913. Business Cycles. Berkeley: University of California Press.

———. 1927. Business Cycles: The Problem and Its Setting. New York: NBER.

Morgan, Mary S. 1990. The History of Econometric Ideas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morgenstern, Oskar. 1928a. “Aufgaben und Grenzen der Institute für Konjunkturforschung.” In Beiträge zur Wirtschaftstheorie. Part II: Konjunkturforschung und Konjunkturtheorie, Schriften des Vereins für Sozialpolitik, Vol. 173/II, edited by Karl Diehl, 337–53. Munich and Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.

———. 1928b. Wirtschaftsprognose. Eine Untersuchung ihrer Voraussetzungen und Möglichkeiten. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer.

———. 1935. “Organisation, Leistungen und weitere Aufgaben der Konjunkturforschung.” Publications of the Statistical Institute for Economic Research No. 1. Sofia: State University.

Neisser, Hans. 1928. Der Tauschwert des Geldes. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

Neisser, Hans, and Franco Modigliani. 1953. National Incomes and International Trade: A Quantitative Analysis. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Predöhl, Andreas. 1928. “The Theory of Location in Its Relation to General Economics.” Journal of Political Economy 36: 371–390.

Schmidt, Carl T. 1931a. “The Austrian Institute for Business Cycle Research.” The Journal of Political Economy 39 (1): 101–3.

———. 1931b. “The German Institute for Business Cycle Research.” The American Economic Review 21 (1): 63–66.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. 1954. History of Economic Analysis. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. 2000. Briefe/Letters, edited by Ulrich Hedtke and Richard Swedberg. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck.

Take, Gunnar. 2017. “American Support for German Economists after 1933: The Kiel Institute and the Kiel School in Exile.” Social Research 84 (4): 809–30.

———. 2018. “One of the Bright Spots in German Economics.” Jahrbuch für Wirtschaftsgeschichte 59 (1): 251–328.

———. 2019. Forschen für den Wirtschaftskrieg. Das Kieler Institut für Weltwirtschaft im Nationalsozialismus. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter.

Trautwein, Hans-Michael. 2017. “Hans Neisser: The ‘Guardian of Good Theory’.” Social Research 84 (4): 929–54.

Wagemann, Ernst. 1928. Konjunkturlehre. Eine Grundlegung zur Lehre vom Rhythmus der Wirtschaft. Berlin; English translation as Economic Rhythm. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1930.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hagemann, H. (2021). The Formation of Research Institutes on Business Cycles in Europe in the Interwar Period: The “Kiel School” and (In)Voluntary Internationalization. In: M. Cunha, A., Suprinyak, C.E. (eds) Political Economy and International Order in Interwar Europe. Palgrave Studies in the History of Economic Thought. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47102-6_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47102-6_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-47101-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-47102-6

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)