Abstract

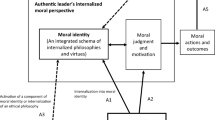

There is much debate about whether the morality of a leader influences their authenticity or transformational efficacy. Drawing on the writings of Aristotle, sacred texts, and contemporary leadership literature, this analysis examines the importance of a leader’s character, positing the necessity for universal acceptance, consistency, and moral distinction for a leader to be viewed as authentic or transformational. Hence, to be an authentic leader, character and conduct must be consistently apparent publicly and privately. Likewise, to be a transformational leader, ethical conduct and commitment to the leader’s espoused vision should be modeled and reinforced systemically. Therefore, the shared moral components of both authentic and transformational leadership styles represent moral forms of leadership because they both call for integrity and consistency of espoused beliefs and measurable action.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Bass and Steidlmeier (1999) proffered that for many moral analysts, leadership is a many-headed hydra that alternately shows the faces of Saddam Hussein and Pol Pot alongside leaders like Nelson Mandela and Mother Theresa. This raises questions concerning the place of moral character in leadership and how it affects the legitimacy of the programs and accomplishments of leaders. Does a leader’s morality contribute to the authenticity of their leadership?

In international politics, there are examples of leaders who have made the argument that it is not necessary to view morality in absolute terms, but rather be informed by prudence, flexibility, and the common good over the long term (Walker, 2006). From this perspective, the only universalities are the interests that exist, fulfilled with the broadest view of the common good possible. In fact, according to Walker, realists believe that human nature is selfish and that people will behave according to the rational pursuit of self-interest over the short term. This certainly reinforces the question of whether character provides a moral distinction for authentic leadership. This chapter explores this question from both philosophical and biblical perspectives.

Character and Morality

According to Lanctot and Irving (2010), it was Aristotle, drawing on Plato, who first articulated the nature of character and virtue by considering the telos (end) of humanity. Thus, Aristotle spoke of virtues as character traits that are the means of bringing a person from what they happen to be to what they could be by realizing essential nature. Furthermore, Aristotle emphasized that right action can only flow from right character. Similarly, Jesus disagreed with the thought of a dichotomous lifestyle, especially in leadership, using prophets as an example:

You will know them by their fruits. Are grapes gathered from thorns, or figs from thistles? So, every sound tree bears good fruit, but the bad tree bears evil fruit. A sound tree cannot bear evil fruit, nor can a bad tree bear good fruit. (Matt 7:16–18, RSV)

Keener (1993) reported that prophets were viewed as false if they led people away from the true God (Deut 13) or if their words did not come to pass (Deut 18:21–22). Although the rabbis allowed prophets to temporarily suspend a teaching of the law in the same way rabbis themselves did. However, if a prophet denied the law itself or advocated idolatry, they were false prophets. But Jesus raised the bar and took it beyond the veracity of the prophets’ words—if the prophets do not live right, they are false (Matt 7:21–23). In Jesus’ view, it was quite clear:

No good tree bears bad fruit, nor does a bad tree bear good fruit. Each tree is recognized by its own fruit. People do not pick figs from thorn bushes, or grapes from briers. The good man brings good things out of the good stored up in his heart, and the evil man brings evil things out of the evil stored up in his heart. (Luke 6:43–45, NIV)

Consequently, for both Aristotle and Jesus, character was the very fountain of a virtuous life. For, right action can only flow from right character (Aristotle), and the good person brings good things out of the good stored up in their heart, while the evil person brings evil things out of the evil stored up in their heart (Jesus). No wonder then, Lanctot and Irving (2010) defined virtue as a set of related personal attributes or dispositions that (a) is universal and not contextual, (b) has moral implications that extend beyond the individual, (c) recognized that possessing it without excess is considered good while lacking it is harmful, and (d) can be attained through practice. It follows, therefore, a person of virtue and character, should be one possessed of these qualities in a universally acceptable, morally distinct, and measurably consistent.

Character and Authentic Leadership

Quite in line with Lanctot and Irving’s (2010) argument, several studies found that moral character augments followers’ perceptions of a leader’s authenticity. For example, Fields (2007) predicted that authentic leaders whose actions were consistent with their own beliefs will likely have more influence on followers, in part because such followers interpret authenticity as evidence of a leader’s reliability. Thus, an authentic leader is more likely to be emulated by followers because they are a credible role model. This may be because authentic leaders are characterized as having (a) heightened capacity to effectively process self-information, which includes values, beliefs, goals, and emotions; (b) ability to use their self-system to regulate behaviors while acting as a leader; (c) high levels of clarity of self; and (d) ability to manage tension between self and social demands (Chan, Hannah, & Gardner, 2005). Hence, even for a new leader, if there is a perception of credibility, the uncertainty among followers is greatly reduced. This produces confidence in both the leader and the team. It is no wonder then the Bible sets out clear standards for biblical leadership based on an individual’s moral character traits.

For example, there were qualifying standards presented in I Tim 3:1–7. This pericope declared that any person who aspires to a leadership position must possess certain character traits and qualities to qualify for a role leading others. Advising Timothy on the appointment of leaders within the nascent church, Paul emphasized the need for definite character qualities evident in the lives of those who sought top leadership positions. The Apostle Paul acknowledged leadership was open to all who met the stated qualifications and the desire to be a leader was a noble pursuit (1 Tim. 3:1), and certain qualities were to be the hallmark of authentic Christian leadership (1 Tim. 3:2–3). These qualifications needed to be observable in the perspective prospective leader, especially given the heresy that had spread in Ephesus (Keener, 1993). Such authenticity was therefore predicated upon a proven track record of a consistent good conduct. It is noteworthy that between verse 2 and verse 7, the word must was repeated four times and was found at the opening of each verse, except for verse 3. In other words, the possession of these character traits was imperative and a prerequisite to ascending to any leadership position. Hence, according to Paul, the first imperative for leadership was for the aspirant to be above reproach: “Now a bishop must be above reproach, the husband of one wife, temperate, sensible, dignified, hospitable, an apt teacher, no drunkard, not violent but gentle, not quarrelsome, and no lover of money” (1 Tim 3:2–3, RSV). This appeared to be a list of character qualities that demonstrate self-discipline. Clarke (2006) posited that the Greek word anepileepton, translated as above reproach, was used for a person against whom no evil could be proved. Clarke further asserted, the word was a metaphor, taken from the case of an expert and skillful warrior, who so effectively defended every part of his body such that it was impossible for his antagonist to give one hit. Likewise, an authentic leader must be one who has so disciplined themselves in an irreprehensible manner. Paul, therefore, directed leaders to refuse to follow the path of polygamy, a common practice in Palestine (Keener, 1993). Rather, leaders have sufficient discipline to be a husband of only one wife. Such a leader had to equally take charge of emotions and appetites, and be willing to take in trustworthy travelers as guests, a practice that was a universal virtue at the time. Thus, according to Paul, the qualifying candidates for leadership had to be masters of their lives, showing self-control and mastery of passions. They likewise had to have restraint where money, wine, or violent temper was concerned (DeSilva, 2004). This must have been fundamentally critical, especially for the church, because such leaders were not only to be role models but also to serve as transformational leaders promoting humility in a decadent society. Hence, the authenticity of leaders was judged by their character and conduct, both in society and at home.

Character and Transformational Leadership

According to Burns (1995), transformational leadership occurs when an individual engages with others in such a way that both the leader and their followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality. This level of engagement challenges the follower to “transcend their own self-interest” (Yukl, 2013, p. 322) and results in the follower doing more than was originally expected. Thus, transformational leadership, though also goal-oriented, incorporates the preeminent role of morality at its core, with the leader playing a critical role in shaping the values and ethics of the follower.

Transformational leadership is comprised of four dimensions: charisma or idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration (Yukl, 2013). It seems likely the most critical component for impacting the character and behavior of the follower is idealized influence. This is the degree to which the leader behaves in admirable ways that, in turn, cause followers to identify with the leader. Such leaders display conviction, they take stands, and they appeal to followers on an emotional level. Accordingly, Bass and Steidlmeier (1999) argued that effective leaders not only influence the attitudes and actions of followers but also do so from an established code of ethical and moral values.

In scripture, there are many examples of these values and moral codes that represent foundational teachings. One such example was God’s charge to Joshua when commissioning him to lead the nation of Israel into the Promised Land:

This book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate on it day and night, that you may be careful to do according to all that is written in it; for then you shall make your way prosperous, and then you shall have good success. (Joshua 1:8)

Thus, the book of the law was intended to be Joshua’s leadership guide if he was to be prosperous and experience good success. It was this book that shaped Joshua’s character and defined his morality. Understandably therefore, Fields (2007) suggested that to be effective, leaders must not only behave reliably in ways consistent with their personal values but also adhere to values that are consistent with objective moral codes. In this regard, Bass (1985) originally argued that transformational leaders could wear the black hats of villains or the white hats of heroes, depending on their values. Bass and Steidlmeier (1999) later considered this to be mistaken. “Only those who wear white hats are seen as truly transformational. Those in black hats are now seen as pseudo-transformational” (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999, p. 187). In other words, those leaders whose lives and actions are incongruent with moral principles, while they may be transformational, are inauthentic as transformational leaders. Bass and Steidlmeier referred to these false messiahs and tyrants of history as pseudo-transformational leaders. They fit Jesus’ categorization of false prophets whose trees and fruits are irreconcilable.

To further refine this concept of morality as evidence of authentic transformational leadership, Walker (2006) made it clear it is not only the ends of the process that must be moral but also the means. In Walker’s view, this was a crucial distinction from alternative views of leadership such as Machiavellianism. For example, in Machiavelli’s view, true virtue was accomplishing one’s goals or ends on behalf of one’s constituents irrespective of the means (Mansfield, 1996). In fact, Machiavelli’s writings could be interpreted to mean leaders could not actually be that good, but rather goodness and virtue are only defined and established in a social, political context. Thus, for Machiavelli, virtue ethics were focused upon what makes a good person as opposed to a good action, implying that morality and leadership are distinct constructs that do not have to exist concurrently in the person of a leader. Many contemporary scholars challenged this divergent view of morality and leadership. For instance, Palanski and Yammarino (2007) reported that empirical research has linked various aspects of morality and integrity with transformational leadership. For example, Peterson (2004) noted that a leader’s integrity (defined as the absence of unethical behavior) was positively correlated with the moral intentions of his or her followers. Likewise, in a qualitative research about employees’ psychological expectations about their managers, Baccili (2001) found that integrity was often cited by participants as a key expectation. She determined that employees expect integrity from their immediate supervisors, even if the overall organization was not perceived to encourage integrity. Likewise, in a study on follower expectations of a leader, Oginde (2011) found that personal character and integrity was a common theme among those interviewed. The respondents described the good leader and admired leaders with phrases like transparent, honest, accountable, has character, has integrity, means what they say, and says what they mean.

In Trevion, Brown, and Hartman’s (2003) definition, integrity was equated with consistency—doing what you say, following up, and following through. It is a pattern that when you say something, people believe it because historically when you have said it, you have follow through. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that the perception of a leader as a person of integrity will produce an idealized influence with followers. Furthermore, according to Trevion, Brown, and Hartman (2003), such leaders hold followers accountable to standards by creating a system that reinforces ethical behavior and admonishes ethical violations. In this way, transformational leaders convey to followers how individuals win and lose within the organization. To this point, Fairholm (1998) asserted that a leader’s task is to integrate behavior and values. Likewise, Heifetz (1994) encouraged “adaptive work … to diminish the gap between the values people stand for and the reality they face” (p. 22). These findings all point to the crucial link between morality and effective transformational leadership.

Conclusion

Considering the above arguments, Avolio, Luthans, and Walumbwa’s (2004) definition of authentic leaders seems to be well supported. These authors viewed authentic leaders as those who are deeply aware of how they think and behave. Such leaders are consistently perceived by others as “aware of their own and others’ values/moral perspectives, knowledge, and strengths; aware of the context in which they operate; and [those] who are confident, hopeful, optimistic, resilient, and of high moral character” (p. 4).

Furthermore, Bass and Steidlmeier (1999) had strong criticism for those who merely present the impression of authenticity:

Pseudo-transformational idealized leaders may see themselves as honest and straightforward and supportive of their organization’s mission but their behavior is inconsistent and unreliable. They have an outer shell of authenticity but an inner self that is false to the organization’s purposes. They profess strong attachment to their organization and its people but privately are ready to sacrifice them. Inauthentic CEOs downsize their organization, increase their own compensation, and weep crocodile tears for the employees who have lost their jobs. (p. 188)

Jesus likewise spoke firmly to the inauthentic leaders he encountered:

You hypocrites! You are like whitewashed tombs, which look beautiful on the outside but on the inside are full of dead men’s bones and everything unclean. In the same way, on the outside you appear to people as righteous but on the inside you are full of hypocrisy and wickedness. (Matt 23:27–28)

It is clear, then, that authentic transformational leadership (Arenas, Tucker, & Connelly, 2017; Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999; Zhu, Avolio, Riggio, & Sosik, 2011) carries with it a component of high moral character as an indispensable leadership trait. It embraces the congruence between the leader’s beliefs and their practice. It displays an integral lifestyle that is both moral and transformative. Consequently, it rejects anything that is to the contrary. It is truly authentic in every sense of the word.

References

Arenas, F. J., Tucker, J., & Connelly, D. A. (2017). Transforming future air force leaders of tomorrow: A path to authentic transformational leadership. Air & Space Power Journal, 31(3), 18–33.

Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2004). Authentic leadership: Theory building for veritable sustained performance. Gallup Leadership Institute, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, 4.

Baccili, P. A. (2001). Organization and manager obligations in a framework of psychological contract development and violation. Unpublished dissertation, Claremont Graduate University.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181–217.

Burns, J. M. (1995). Transactional and transforming leadership. In T. J. Wren (Ed.), The leader’s companion: Insights in leadership through the ages. New York: Free Press.

Chan, A., Hannah, S., & Gardner, W. (2005). Veritable authentic leadership: Emergence, functioning, and impacts. In W. Gardner, B. Avolio, & F. Walumba (Eds.), Authentic leadership theory and practice: Origins, effects, and development. Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

Clarke, A. (2006). Adam Clarke’s commentary. Electronic Database, PC Study Bible (Version 5.0) [Computer Software]. Biblesoft, Inc.

DeSilva, D. A. (2004). An introduction to the New Testament: Contexts, methods, and ministry formation. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

Fairholm, G. W. (1998). Perspectives on leadership: From the science of management to its spiritual heart. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Fields, D. L. (2007). Determinants of follower perceptions of a leader’s authenticity and integrity. European Management Journal, 25(3), 195–206.

Heifetz, R. A. (1994). Leadership without easy answers. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Keener, C. S. (1993). IVP Bible background commentary: New Testament. Downers Grove, IL: Inter Varsity Press.

Lanctot, J. D., & Irving, J. A. (2010). Character and leadership: Situating servant leadership in a proposed virtues framework. International Journal of Leadership Studies, 6(1), 28–50.

Mansfield, H. C. (1996). Machiavelli’s virtue. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Oginde, D. A. (2011). Follower expectations of a leader: Most admired leader behaviors. International Leadership Journal, 3(2), 87–108.

Palanski, M. E., & Yammarino, F. J. (2007). Integrity and leadership: Clearing the conceptual confusion. European Management Journal, 25(3), 171–184.

Peterson, D. (2004). Perceived leader integrity and ethical intentions of subordinates. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 25, 7–23.

Trevion, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations, 56(1), 5–37.

Walker, M. C. (2006). Morality, self-interest, and leaders in international affairs. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 138–145.

Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in organizations (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Zhu, W., Avolio, B. J., Riggio, R. E., & Sosik, J. J. (2011). The effect of authentic transformational leadership on follower and group ethics. Leadership Quarterly, 22(5), 801.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Oginde, D.A. (2020). The Character of a Leader: Authenticity as a Moral Distinction. In: Peltz, D., Wilson, J. (eds) True Leadership. Christian Faith Perspectives in Leadership and Business. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46660-2_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46660-2_4

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-46659-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-46660-2

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)