Abstract

A young woman seeks medical care for vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain. A trauma-informed approach by the clinician enables the patient to disclose several historical indicators that suggest child sex trafficking. Eventually the patient confirms she is experiencing sexual exploitation. The youth is found to be pregnant. The source of her symptoms requires hospital admission. Legal issues arise when the patient resists admission, indicates that she does not want her biological mother to be involved, and requests to be discharged to a potentially dangerous situation. Mandatory reporting laws, confidentiality requirements, adolescent rights, and safe harbor laws are addressed.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

FormalPara Case PresentationA young woman is brought into the emergency department presenting with severe abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding. You are a pediatrician working in the ED that night. The patient tells you her name is Josie, and she is 19 years old. She is accompanied by a woman who identifies herself as Josie’s mother. Josie seems nervous, and glances at the other woman throughout your initial interaction. You think she seems much younger than 19. You notice that she smells strongly of marijuana, that her teeth are yellowing, and that her gums are very light. She appears to be underweight. The patient tells you abruptly that she “knows” she is not pregnant and that she knows this because she took a pregnancy prevention pill after unprotected sex a little over a month ago.

You advise the other woman that per hospital practice you need to speak alone with Josie and that the woman will need to return to the waiting room. She mutters under her breath and glares at you, but complies. You attempt to build rapport with Josie and engender a feeling of safety by asking her if she is warm enough, needs an extra blanket, would like some water or a snack. You tell her you would like to ask her some questions to find out more about her and about her symptoms in order to find out what may be causing the pain and to see if you can help. You tell her she is free to answer or not answer any of the questions, and you ask her if she is willing to talk to you. She says she is, and she responds to your questions by telling you the bleeding started two days ago, has gotten worse over time (changing tampons every few hours now), and the pelvic pain began last night. She speaks quietly, and she is evasive while answering your questions about reproductive history but does tell you she has had gonorrhea in the past, as well as a prior pregnancy with elective termination.

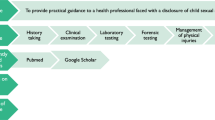

Approach to Care

When interacting with potentially trafficked/exploited patients, it is important to keep in mind some key concepts of the “trauma-informed approach” [1, 2]. With such an approach, the practitioner takes into account the impact of prior traumatic experiences in shaping a patient’s views of self, the world, and other people and in influencing behaviors and attitudes. Trauma-informed care is victim centered (patient’s desires and best interests are given the highest priority) and human rights based. There are five core values upon which a trauma-informed approach is built: (1) physical and psychological safety, (2) trustworthiness, (3) choice, (4) collaboration, and (5) empowerment [3]. The most important value of those five is safety, because without a sense of safety, patients will feel anxiety and stress which will add new trauma, amplify old trauma, and influence their reception of treatment. Therefore, care is taken to facilitate a sense of physical and psychological safety.

Privacy

Safety begins with separation of the patient from the person accompanying them in order to speak with the patient alone. An effective way to do this is to inform the companion that it is your practice’s policy to interview patients alone, so you’ll need them to step out for a few minutes and you’ll be glad to come get them when you are finished. If this is not effective, you can remove the patient from the examination room by indicating they need to come with you for a procedure (x-ray, laboratory testing), then take the patient to a comfortable and private room to talk. It takes time to build rapport, but this is an essential first step in building trust and encouraging the patient to talk about their experiences and needs. Open-ended questions about nonthreatening topics (what the child likes to do; what apps he/she enjoys) can begin to build this rapport. Asking the child if she/he is hungry, thirsty, or cold also conveys concern and a desire to assist.

Building Trust

Two additional components of trauma-informed care are respect and transparency, key ways you can build trust with the patient. It is essential that you convey a sense of respect for the patient and all they have experienced. This can be done by encouraging them to voice their opinions (including their objections), actively listening to what they say, informing them of what you would like to do during the evaluation (before doing it), and obtaining their permission for every step of the process. Asking their opinion about the various steps and encouraging questions and feedback incorporate a strength-based approach and facilitate a sense of agency and control, as does offering the patient choices whenever possible.

Disclosing to Josie Your Mandate to Report

Questions about medical history transition to those about recent mental health symptoms. Josie reports episodic periods of sadness without suicidal ideation. She experiences occasional nightmares and insomnia. You begin asking open-ended questions about her social history, and eventually she reveals that she is actually only 14 years old, and that the woman outside is not her mother. You tell her you’re glad she told you this and would like to find out more if she feels comfortable discussing it. However, since she is below the age of 18 years, you need to let her know something about privacy first. That is, while you want to respect her right to have information kept confidential and will make every effort to abide by that, there are two conditions under which you will need to speak with others about your conversation. Those conditions include if you are concerned that Josie is not safe or that Josie may harm someone else. Under those circumstances you would need to talk with other professionals in order to solicit their help, since safety is of the utmost importance. If this happens, you and Josie would discuss how you would go about notifying the other people. You ask if she has any questions about that and she says “no.”

Confidentiality

Informing the patient of the limits of confidentiality before beginning a discussion of sensitive issues is important so that the child does not feel betrayed later, should you disclose the need to involve authorities in the case. While discussing the limits of confidentiality early in a discussion may inhibit the patient from disclosing potentially important information, it is critical to respect their rights to privacy and choice [6]. In many cases, if sufficient time is spent building rapport and trust, a patient will decide to discuss their situation despite knowledge of confidentiality limits [7].

Josie Opens Up

You thank Josie for her honesty and tell her that you are concerned that she did not feel comfortable revealing her age at first and that the woman outside is pretending to be someone else. You ask her if she is comfortable telling you why she said she is 19 years old, and why the woman pretended to be her mother. Josie hesitates and does not meet your eye. You allow some silence and do not rush to fill the gap.

You are sitting at eye level with Josie, with an open posture. Josie tells you the woman is a ‘friend’ she met while ‘on the run.’ She pauses and at length you ask an open-ended question, “Can you tell me a bit more about that? About your being on the run and meeting this woman?” Your voice is calm, nonjudgmental, and conveys interest. Josie tells you she ran away 3 months ago because she ‘doesn’t get along’ with her mom, and she met this woman at a bus stop. The woman introduced her to her boyfriend and offered to let Josie stay with them for a while. You would like to know more about Josie’s difficult relationship with her mother but do not interrupt the flow of Josie’s story and decide to come back to this later. Instead, you nod, repeat back a bit of what Josie said (which conveys interest and the fact that you are listening.) “So she told you that you were welcome to stay with her and her boyfriend. Tell me about that…”

The Value of Open-Ended Questions and Silence

Open-ended questions (e.g., “Then what happened?”) are a helpful way to elicit information and give the speaker control over the conversation. They will often lead to a narrative with important details that can inform your evaluation and recommendations for referrals. Leading questions (those which introduce new information not disclosed by the patient) and suggestive questions (those that imply a preferred response) should be avoided, as should any question that implies blame or judgment. Furthermore, it is common for the flow of the story to be scattered or nonlinear if the child has experienced trauma. Allow the child to tell the story in the order they wish to, and come back to parts you wish to elaborate on later. Do not rush to fill silences, for these may offer the child time to think and to offer sensitive and critical information.

Josie’s Disclosure

Josie goes on to tell you that she stayed in an apartment with a few other girls, and that these girls seemed ‘young’. They would disappear at night and come back early in the morning, and talk about making money and getting drugs. After a few days, Josie’s friend told her about the ‘stroll’ and asked her if she wanted to make some money. You ask, “What is ‘the stroll’?” She tells you this is X Street, where the ‘players’ are and where ‘you do sex for money’. You follow up with another open-ended question, “So then what happened?” She says the woman’s boyfriend convinced her to do it, telling her she’d make lots of money because she’s so beautiful. Josie was scared, and when they got there she didn’t want to get out of the car, but he punched her and made her get out. She had sex with three men that night, and as many men nearly every night since then. When she ‘earns enough’ the woman and boyfriend give her methamphetamine; sometimes she uses it to stay awake when she ‘works’. She also uses marijuana nearly every day. She does this to ‘make it easier to handle.’ She wants to leave, but another girl tried to do this and the boyfriend beat her up. Josie doesn’t want to get beaten up. She doesn’t feel she can leave, and she is afraid of the woman and her boyfriend.

Handling a Disclosure

Josie is providing important information that allows you to assess risk of exploitation (she has actually disclosed that it is occurring), evaluate safety, and determine the possible need for after-care referrals, such as a formal assessment for substance abuse. Once Josie finishes her narrative, you may want to follow up with additional questions about injuries from this and other possible acts of violence, condom use, anogenital signs/symptoms, etc. These are important issues that will help you with your medical assessment. However, you would want to avoid irrelevant questions that will not provide you with useful information (e.g., “How much did you charge for each sex act?”), since these questions may elicit distress and anxiety and are inappropriate for the situation.

While Josie is describing what she has experienced, it is important for you to pay close attention to verbal and nonverbal cues that might signal traumatic stress and anxiety. You do not want to retraumatize her with your evaluation, if at all possible. Should you notice signs of distress (loss of eye contact, flat affect, nervousness, tears, fidgeting, etc.), it is important to take steps to alleviate the stress. This can be done by pausing, acknowledging the difficulty of what the patient has experienced, acknowledging her feelings, and emphasizing the strength it takes to talk about stressful experiences. You may want to offer her control by asking, “I can see this is very hard for you. Would you like to take a break or continue to tell me about it?”

Supporting Josie

You tell Josie that you are very glad she felt she could tell you about what is happening, that this takes a lot of courage. You acknowledge aloud that she has been through a great deal and is a very strong young woman. You tell her you are very concerned about her safety, and for this reason you are going to need to tell authorities about what is happening. You need police and child protective services to help offer assistance, to provide services you can’t provide. She becomes upset about this. You ask her to talk about why she doesn’t want anyone else to know. She tells you she is afraid of what the boyfriend will do, and afraid she’ll be sent back to live with her mother. She doesn’t want to live with her mother, but wants to go back to her former boyfriend, who is 24 years old. You reiterate your concern and your desire to help. You emphasize that it is important for her to tell the child protective services worker about her concerns and her desire not to return to her mother’s care. Also it’s important for her to tell police about her concern regarding the boyfriend’s violence. You encourage her to voice her opinions, as these are critical for others to know. You ask her for her thoughts on how you and she should go about informing authorities. Does she want to tell the police and the protective services worker herself? Does she want you to call them? Or would she prefer for both of you to talk to them?

A Careful Balancing Act

While you cannot ignore your mandatory reporting requirements, you can allow Josie as much control over the situation as possible. Encouraging her to help you decide how to contact authorities, talking about other referral options, and seeking her opinion about those options (you will need to obtain her consent to make nonmandated victim service referrals, such as to an anti-trafficking nonprofit organization) help her to feel respected and be able to impact her situation.

Addressing the Chief Complaint

You tell Josie that before you call anyone, you want to address the main issue: the cause of her pain and bleeding. You describe the general physical exam and the anogenital and speculum exams. You ask permission to do these exams. She agrees, albeit reluctantly. You assure her that you will explain all that you are doing during the exam and will stop if Josie becomes uncomfortable. With Josie’s permission, you ask a nurse to assist during the exam. The nurse provides emotional support to Josie and monitors her for signs of distress. During the anogenital and speculum exams, you notice a hymenal laceration and two small vaginal contusions. All injuries are carefully documented in her chart. The injuries do not require treatment. There is no vaginal or cervical discharge; a small amount of bright red blood is in the vaginal vault. After completing the exam and allowing Josie to dress and get comfortable, you ask about the cause of the vaginal trauma. Josie tells you she was ‘raped with a bottle’ two days ago. There was pain during the event and a small amount of bleeding thereafter. Later that day, she began bleeding more heavily, as above.

Trauma-Informed Physical Exam

The trauma-informed approach extends to the physical exam and diagnostic evaluation [2]. It is important to explain all the steps of the process before beginning them and to obtain patient permission to proceed. This allows patient control and maintains transparency. Keep attuned to signs of distress during the exam, and take steps to minimize retraumatization. For example, a child who has had a gang rape digitally recorded and been threatened with posting the video online may become very agitated by the appearance of a camera for injury documentation. You would need to ask permission to use a camera and respect the patient’s response. If she becomes upset during the anogenital exam (this is common), take breaks, explain each step, and acknowledge the strength it takes to undergo the exam. When you are contemplating STI, pregnancy, and/or drug testing, it is critical to obtain permission for these tests, after an explanation of what they entail.

In this case, Josie has obvious anogenital injuries, but in many cases the exam will be unremarkable, even with a history of multiple episodes of vaginal and/or anal intercourse [8, 9]. There are reasons for this: the adolescent hymen is able to distend to accommodate objects larger than its resting diameter without sustaining injury, as is the anus; and when injuries do occur, they typically heal within a few days to weeks, without scarring [10].

[See Chap. 16 Table 16.1, for information about the trauma-sensitive gynecologic exam.]

Evaluating and Examining Josie

You discuss your recommendations for further workup: urine testing for pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections; serum testing for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C; and complete blood count to test for anemia. Because her last tetanus booster was greater than 5 years ago, you recommend tetanus booster vaccine for the dirty wound. You also recommend prophylaxis for gonorrhea, chlamydia and trichomonas. You discuss the pros and cons of HIV PEP. You ask Josie what she thinks about this course of action and if she has any questions. Josie agrees to the evaluation.

The point-of-care urine pregnancy test is positive. You ask Josie how she feels about the result and she simply says that she’s ‘not surprised’ and that she doesn’t want to talk about it. You discuss the need for a transvaginal ultrasound, and she agrees to the procedure. The ultrasound shows a sub-chorionic hemorrhage, and you recommend admission for observation. You tell Josie that this will help you to provide better care, and will also give Josie some time to think about things. You’re glad to talk with her at any time, about the pregnancy or any other issues. Josie seems nervous and says she doesn’t want to be admitted; she wants to leave. She asks when the other woman will be allowed to come in. You offer to contact her real mother, but she doesn’t want her mother to know what is happening. She tells you she wants to go, will ‘work things out with the woman and her boyfriend,’ and will then go live with her 24-year-old ex-boyfriend.

Mandatory Reporting

Healthcare professionals are required to report suspected child abuse or neglect to any law enforcement official “authorized by law to receive such reports,” and you do not need the individual’s agreement in order to make this disclosure [11]. [See Chap. 3 section “Reporting” for nuances with adolescents]. State law may require more specific requirements as to whom clinicians must report and what information must be reported.

Adult abuse may be reported to law enforcement in specific circumstances, including: if the individual agrees; if the report is required by a different law; if expressly authorized by law, and based on the exercise of professional judgment, the report is necessary to prevent serious harm to the individual or others; or in certain other emergency situations [12]. In these cases, you may be required to give the individual notice of the report [12].

Healthcare professionals are required to report the amount of information that is the minimum necessary needed to accomplish the intended purpose of disclosure, unless more is required by a different law [13, 14]. Healthcare organizations typically have policies regarding what information this entails sharing. When it is reasonable, the clinician may rely upon the representation of the law enforcement official regarding what information is the minimum necessary for their lawful purpose [14].

Typically, a clinician should report when the clinician suspects or has reason to believe that a child has been abused or neglected [15]. Mandated reporters of child abuse are required to report the facts and circumstances that led them to believe the child is being abused or neglected [15]. Clinicians should ensure that they also are following the state reporting requirements and should contact their organizations’ general counsel if they have questions.

According to the Polaris Project, one in seven endangered runaways who were reported to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children was likely a sex trafficking victim, and of those, 88% were in the care of social services or foster care when they ran away [16]. According to the National Foster Youth Institute, 60% of all child sex trafficking victims have histories of child welfare involvement [17].

Josie should be referred to an attorney and to a social worker to help determine the best course of action for her. State laws vary regarding custody and emancipation, so Josie would need to be directed to someone who understands her state’s requirements.

Whether or not the clinician is required to disclose Josie’s pregnancy is a complicated question. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) defers to state and other laws to determine the rights of parents to access and control protected health information of their minor children. Parents, or a minor’s other personal representatives, typically are allowed access to the child’s protected health information. However, if the minor is subject to certain exceptions, this is no longer the case. For example, if the minor is emancipated, they are treated as a legal adult [18]. In some states, minors are considered emancipated for medical purposes when they are pregnant. Furthermore, when a clinician believes that “an individual, including an unemancipated minor, has been or may be subjected to domestic violence, abuse, or neglect by the personal representative, or that treating a person as an individual’s personal representative could endanger the individual, the covered entity may choose not to treat that person as the individual’s personal representative, if in the exercise of professional judgment, doing so would not be in the best interests of the individual” [13] [4]. If Josie’s mother were involved in her trafficking situation, the clinician could choose not to treat her as Josie’s personal representative because it would not be in Josie’s best interest.

Josie’s indication that she wishes to leave the hospital without being admitted and without further medical care raises the issue of whether the healthcare professional faces legal implications if the patient leaves against medical advice (AMA). There is no perfect answer. The clinician has the option of calling Child Protective Services (CPS) to arrange for protective custody so that treatment can continue right away. The clinician also may choose to discharge Josie with a note in the medical record indicating “discharged AMA” and with detailed follow-up instructions, including possibly an instruction to return – although that doesn’t seem promising in this scenario.

Above all, the decision to report the abuse depends on the medical determination as to the impact a delay in treatment would have on Josie’s long-term well-being. An AMA discharge does not necessarily immunize a clinician from liability; however it does affirm the clinician’s intent to provide further treatment [5]. Josie should be discouraged from leaving AMA and instead should be given information relative to the dangers and risks inherent. Likewise, the healthcare professional should reiterate that CPS will be informed due to mandated reporting requirements. All interactions should be clearly documented in the medical record, and a final attempt at referring Josie to legal counsel should be made.

There are several other reasons why a healthcare professional should refer Josie to legal representation. If Josie has any pending cases or convictions relating to her victimization, an attorney may be able to help her fight these through vacatur, expungement, and safe harbor laws: some states have “safe harbor” laws, which means that minors who have been prostituted will not be prosecuted for prostitution-related crimes. If Josie has already been convicted of prostitution-related crimes, an attorney may be able to help her through processes known as vacatur and expungement. Vacatur is when a conviction is set aside as if it never happened, while expungement is when convictions are removed from a person’s record.

Each of these processes can help Josie move forward without the burden of a criminal record, and it is important to let Josie know that she has this opportunity.

Documentation

You are now documenting your evaluation of Josie. It is important to balance detail with the desire for confidentiality, knowing that authorities are likely to read your report. You want future medical professionals to have important health and safety information, but you also want to respect the child’s privacy. When describing what the child told you, document as much of her responses verbatim as possible. Ideally you are not taking notes during your discussion with Josie, but to the extent that you can remember the wording of your questions and her comments, it is important to document this. Describe injuries carefully (written description of location, type of injury, approximate size, shape, color, etc.), and document the child’s affect, general state of health, untreated medical conditions, and acute conditions. Remain objective in your documentation and do not write anything you are not prepared to say in court, under oath.

It is important for your institution to consider privacy issues for patients with a history of human trafficking. Policies and protocols already in place to protect highly sensitive information (e.g., mental health records) may also apply to cases of trafficking. Access to information regarding a patient’s trafficking experiences should be limited to those who are working with the patient, and processes must be in place to restrict access by other medical staff and outside persons who lack legal rights to the record.

List of Resources Pertinent to the Chapter Topic

-

1.

NHTRC – National Human Trafficking Hotline: https://humantraffickinghotline.org/

-

2.

CSE Institute and ABA: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/domestic_violence/survivor-reentry-project/

-

3.

Guttmacher Institute: https://www.guttmacher.org/

-

4.

American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement – Child Abuse, Confidentiality, and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, 2010: https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/125/1/197.full.pdf

-

5.

Shared Hope International: https://sharedhope.org/

References

Substance abuse and mental health services administration [Internet]. 2016. Trauma-informed approach and trauma-specific interventions. Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma-interventions.

Substance abuse and mental health services administration trauma and justice strategic initiative [Internet]. 2014. Concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach; [1–27]. Available from: https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/sma14-4884.pdf

Wilson C, Pence DM, Conradi L. Trauma-informed care. Encyclopedia of social work [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 May]. Available from: https://oxfordre.com/socialwork/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.001.0001/acrefore-9780199975839-e-1063. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.1063.

Zimmerman C, Watts C. World Health Organization ethical and safety recommendations for interviewing trafficked women. 2003. Health policy unit, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Available from: https://www.who.int/mip/2003/other_documents/en/Ethical_Safety-GWH.pdf.

Kaltiso SO, Greenbaum VJ, Agarwal M, McCracken C, Zimitrovich A, Harper E, Simon HK. Evaluation of a screening tool for child sex trafficking among patients with high-risk chief complaints in a pediatric emergency department. Soc Academic Emerg Medicine. 2018;25(11):1193–1203.

Adams JA, Harper K, Knudson S, Revilla J. Examination findings in legally confirmed child sexual abuse: it’s normal to be normal. Pediatrics. 1994;94(3):310–7.

Smith TD, Raman SR, Madigan S, Waldman J, Shouldice M. Anogenital findings in 3569 pediatric examinations for sexual abuse/assault. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2018;31:79–83.

McCann J, Miyamoto S, Boyle C, Rogers K. Healing of hymenal injuries in prepubertal and adolescent girls: a descriptive study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1094.

Uses and disclosures for which an authorization or opportunity to agree or object is not required, 45 C.F.R. § 164.512 (2016).

Uses and disclosures of protected health information: general rules, 45 C.F.R. § 164.502 (2013).

Other requirements relating to uses and disclosures of protected health information, 45 C.F.R. § 164.514(d) (2013).

U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. When does the privacy rule allow covered entities to disclose information to law enforcement [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Office for Civil Rights; 2004 [updated 2013 July 26]. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/faq/505/what-does-the-privacy-rule-allow-covered-entities-to-disclose-to-law-enforcement-officials/index.html.

Child welfare information gateway [Internet]. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau; 2016. Mandatory reporters of child abuse and neglect; [1–61]. Available from: https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubpdfs/manda.pdf.

Polaris Project. The facts [Internet]. 2016; [cited 2019 May]. Available from: https://polarisproject.org/human-trafficking/facts.

National Foster Youth Initiative. Sex trafficking: sex and human trafficking in the U.S. disproportionately affects foster youth [Internet]. [cited 2019 May]. Available from: https://www.nfyi.org/issues/sex-trafficking/.

Michon K. The ins and outs of minor emancipation – what it means and how it can be obtained [Internet]. Nolo; [cited 2019 October]. Available from: https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/emancipation-of-minors-32237.html.

U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. Guidance: personal representatives [Internet]. Washington, D.C.: Office for Civil Rights; 2013. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/guidance/personal-representatives/index.html.

Alfandre D, Schumann JH. What is wrong with discharges against medical advice (and how to fix them). JAMA. 2013;310(22):2393–4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rhodes, S., Mersch, S., Greenbaum, J. (2020). Medicolegal Aspects and Mandatory Reporting. In: Titchen, K., Miller, E. (eds) Medical Perspectives on Human Trafficking in Adolescents. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43367-3_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-43367-3_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-43366-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-43367-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)