Abstract

For social workers to work critically they need to be well versed in a pedagogy that equips them with the necessary knowledge, skills, and ability for lifelong learning and critical thinking. This chapter examines the key concepts of a critical pedagogy, its theoretical underpinnings and associated learning strategies and establishes its centrality in framing a critical practice for use in professional social work supervision. Critical pedagogy facilitates constant questioning and reflection and ongoing dialogue on, and critique of, the socio-political, economic and cultural power relations within the organisation as well as more broadly in the community and society at large. Its use in supervision has the potential to open up discussions and interaction beyond what is known to spaces where new knowledge, theory, practice options, and broader societal concerns are explored. It encourages ‘deep learning’ that can shepherd a transformational opportunity for new learning. Nothing begets learning that stimulates curiosity and the desire to learn more when a good supervisor and eager learner meet in supervisory relationship with an ultimate end to achieve justice for all.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This chapter examines the key concepts of a critical pedagogy, its theoretical underpinnings and associated learning strategies as both a process and teaching tool to support critically informed social work practitioners. Social workers are concerned with the ‘social spaces’ where injustices occur, where people are marginalised, excluded, or stigmatised as ‘bludgers’ and the like and opportunities for their well-being are denied (Mendes, 2017; Noble, Gray, & Johnston, 2016). Working in the ‘social’ involves empowering and liberating people from the margins, who are denied justice and human rights. It involves looking at the system of local and global governance, economic, political, and social relations that contribute to their oppression (Baines, 2011). If social work’s mission is to foster human rights and social justice outcomes for service users then they require the means and processes to ensure they are equipped for the task (Noble et al., 2016; Noble & Irwin, 2009).

Critical social work focuses on the elimination of domination, exploitation, oppression (internally and externally held) and all undemocratic and inequitable social, political, and economic relations that marginalise and oppress many groups in society; privileging a few, while oppressing the many (Baines 2011; Lundy 2011; Morley, Macfarlane, & Ablett, 2014). So, the questions are: How are practitioners supported in this mission? How do social work teachers prepare their students for this task? What educational material, teaching tools, processes and practices are available to equip new graduates with the practice skills to “promote social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people” (IASSW Global definition, 2014)?

The answer to the above questions is, I suggest, incorporating a critical pedagogy informed by critical theory for use in social work supervision. This then requires supervision to have a critical lens embedded in its practice. For critical supervision to work an understanding of the context that shapes the nature and context of social work and its impact on what it does, the how and the why is paramount. If social workers don’t mark out the social spaces that impact directly on their work and that of the service users, then all this activity and impact is rendered invisible. When invisible the politicians and power elites can exclude the poorer and marginalised members of society and leave them excluded, impoverished. They can cut services, deny there is a problem with poverty, inequality, violence, discrimination and minimise or hide the very real impact these practices have on the lives of service users. Not only do the service users suffer but social work goes unnoticed and marginalised too (Hair, 2015; Noble et al., 2016; Noble & Irwin 2009). The first question to address though is what are the challenges in the current welfare landscape that would demand a critical response? What is the broader social landscape and challenges that unilaterally impact on both service delivery and service user’s experiences, their issues and circumstances, and how well-placed organisations and practitioners are to address them through the use of a critical approach to supervision? (Noble et al., 2016, p. 40). The following sections explore these challenges.

Challenges

National and Organisational Influences

It is generally acknowledged that the culture and context in which social work is currently practiced is complex, unstable, and increasingly governed by fiscal restraints characteristic of neoliberal economics enshrined in the new public management (NPM) (Chenoweth & McAuliffe, 2015; Hughes & Wearing, 2013). NPM as a practice of economic conservatism has brought with it a new set of management practices that has transformed workplace culture in the human services. NPM management argues in favour of the private sector providing welfare services. It promotes private over public, profit over people, corporations over state supported services, individual responsibility over the social contract. Proponents argue that the private sector is more lean, efficient, productive, and cost effective in providing services and delivering programs. NPM discourse argues that citizenship and economic and social benefits are more efficiently determined by labour market participation, economic productivity, and useful employment! In fact, many who have embraced the NPM discourse publicly abhor the idea of universal or even targeted welfare.

The popularity of NPM is fast becoming the raison d’etre for delivering health and welfare services, assessing suitability attached to that assistance and evaluating their effectiveness. In other words, the human service sector has seen a return to a more conservative policy and a highly commercial agenda relying more on the ‘market’ than the state for the provision of welfare programs. Accompanying the neoliberal philosophy of market led services has been a gradual attack on the universality of welfare provisions previously supported by more progressive ‘left-leaning’ governments (Jamrozik, 2009). Calling for an end to the age of entitlement conservative discourse targets people who are unemployed, homeless, poor, disabled, sick and old as draining the limited welfare budget. Services that promote equality of opportunity and protection from poverty are considered too expensive for an underfunded welfare state; the private sector would achieve the same ends but more effectively with less pressure on the public purse. Ideally, the argument goes, is that the public sector should make way for a quasi-market enterprise to contractually deliver programs relieving the Government of any direct responsibility for its citizen’s well-being (Mendes, 2017).

Further, proponents argue that welfare spending should be reduced, and some form of paternalistic government regulation should be employed to discourage reliance on welfare, and non-government and/or volunteer services should replace government as main providers of welfare services and assistance for those who fall between the cracks. Individuals should be more proactive in providing for themselves rather than relying on Government ‘handouts’ (Mendes, 2017.) Individuals and families are primarily seen as responsible for their well-being and productivity and are encouraged to save for, and purchase their own health care, education, social and welfare needs and are blamed if they are unable to provide the funds to buy such benefits that make for a good, healthy life (Gray & Webb, 2016; Mendes, 2017)

This attitude is instrumental in creating a culture of blame. It absolves the state its responsibility to ensure all citizens have access to adequate education, health care, social services, and employment opportunities. This culture of blame also pits people against each other as ‘deserving’ or ‘undeserving’ of government help when their individual resources and opportunities are depleted. Indigenous peoples, refugees and asylum seekers as well the unemployed, the aged, differently abled, homeless people, and single women face social stigma, discrimination, and marginalisation as they struggle to provide for themselves in a culture of diminishing government help (Chenoweth & McAuliffe, 2015; Lundy, 2011; Mendes, 2017). This move towards individualism has replaced the notion of the common good; self-regulation and self-management has replaced a collective responsibility for the well-being of people disadvantaged, marginalise, or discriminated in society especially those people deemed unproductive and ‘idle’.

Organisational-Workplace

To achieve this efficiency and more productivity, NPM brings into the workplace stringent accountability practices including introducing performance monitoring and measurement indices and risk aversion policies, cost-cutting practices such as staff reduction and restructuring, sidelining or defunding previously available ‘free’ essential services (such as services for domestic violence, the homeless and indigenous communities) and prioritising other programs such as work-for-the dole (which sits more with its philosophy of work) (Baines, 2011). These changes in the workplace culture coincided with the weakening of the power of the unions to protect workers’ rights. Working conditions now include flexible hours and pay and conditions, more reliance on a casualised workforce and use of agency staff, increasing use of volunteers, and relying more on offshore processing and call centres for service delivery rather than direct service provision from qualified welfare staff. Increases in accountability practices and workplace reviews led to other changes in government agencies and organisations delivering welfare services. These included restructures to streamline decision-making, increased profit incentives, clients were renamed as ‘consumers’, personalisation of services by offering ‘consumer’ choice and outsourcing services leading to competition among former welfare collaborators and colleagues (Hughes & Wearing, 2013).

The growth of IT services has reduced face-to-face interaction with service users and along with the changes listed above has created a new landscape for welfare delivery and the human service culture. As a result, efficiency, productivity, and cost-cutting have become the norm in providing human service work enabling the government to reduce its spending in this area. These changes have destabilised a previously stable workforce making it extremely difficult to provide service users with certainty, continuity and consistent policy and practice options and standards (Baines, 2011, 2013). This is the climate many social workers are working in thus making the pursuit of social justice informed human rights practice an almost daunting task.

Global Influences

Of course, these national developments are a mirror of the global stage where neoliberal policies of globalism are, via the activities of, for example, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank (WB) and the European Union (EU) promoted and, in many cases, enforced globally. It is globalisation that has entrenched capitalism and free market economies throughout the world and has affected the way individual country’s social welfare and health systems operate (Noble et al., 2016, p. 43). In fact, many argue that it’s the global players that direct and govern (in absentia) western democratic governments (Gray & Webb, 2016; Lundy, 2011). We see this in the gradual adoption of welfare austerity, punitive approaches to individual and social problems and the incursions of for-profit-organisations and interests (such as Transfield and Serco) into service provision consolidating their place as key human service providers (Gray & Webb, 2013; Noble, 2007). This unfettered growth of privatisation of state funded welfare and health services has resulted in welfare provisions becoming lucrative business opportunities for these profit-making industries. Worryingly, not-for-profit organisations are also expanding their for-profit initiatives to cover depleted government budgets (Hughes & Wearing, 2013). A critique of how global multinationals are infringing on welfare and health services is yet to be fully evaluated as most ‘Free’ Trade Agreements are conduced out of the public gaze and scrutiny (Noble, 2007).

So, What Now?

These are some of the social spaces where injustices occur, where people are denied their basic human rights and placed on the margin or made invisible and thereby excluded from the benefits and opportunities essential to their well-being (Noble et al., 2016, p. 13). All these challenges and changes have had a deleterious impact on social work and how practitioners think about themselves as practicing professionals. These changes are exacerbated by the stressful nature of the human service work, high caseloads, increase work pressures to perform, less contact with service users and more administrative and computer-based work (Chenoweth & McAuliffe, 2015; Hughes & Wearing, 2013). Additionally, there are more pressures to hire less qualified workers. Left unresolved these changes and pressures have resulted in low morale and low job satisfaction, high staff turnover, poor practices, loss of professional standards, and a compromised ability to work productively with service users towards social change and empowerment outcomes. The consequence of a depleted welfare state means that under-resourced and over-stressed workers are the only ones left to battle for adequate services for those who are disadvantaged, marginalised, and discriminated against in mainstream society. Social workers are left alone and unsupported to advocate for those who bear the brunt of social stigma and discrimination from the cultural norms that promote economic productivity as the only means of securing citizens’ rights (Chenoweth & McAuliffe, 2015; Mendes, 2017).

It is in this analysis that I argue, along with my more critically informed colleagues, that the human services are facing a moral and philosophical crisis (Hughes & Wearing, 2013; Ife, 2013; Noble et al., 2016). The problems get worse if workplaces do not provide for and support their workers to reflect, strategize, and encourage them to think and practice critically and help them stay true to their emancipatory and transformative values. One way these issues can be addressed is for organisations and managers to support and provide workers with regular and professional supervision. The other is for social work supervisors to adopt a critical pedagogy with a critically informed lens within the supervisory processes to encourage resistance and change in this conservative environment.

Social Work Supervision—Applying a Critical Lens

Social work supervision is generally accepted as a core activity of professional practice whose function is to oversee professional accountability, independent practice, ethical and moral standards and reflection of practice outcomes against professional and organisational goals, processes, policies, and practices (Beddoe & Davys, 2016; Hair, 2015; Noble et al., 2016). More conventional models of supervision draw attention to its administrative, supportive, educational, and mediative functions (Beddoe & Davys, 2016). It is practitioner-centred in relation to the workplace and involves the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of the daily work. There are many ways of reviewing the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of social work supervision from surveillance to support, from ensuring personal survival against stress to quality assurance, from professional development to organisational constraint, from reviewing and monitoring to improving service delivery and increasing job satisfaction and enhancing professional values and ethics (Beddoe & Davys, 2016; Hair, 2015).

Supervision functions well when organisations see themselves as learning organisations that encourage individual growth in order to maximise organisation’s assets and standards. The content can cover practise issues and skill development, linking theory with practice, reviewing past and present cases and activities, refining and enhancing practice skills and knowledge development, reviewing policy initiatives and practice guidelines and planning for the future. Importantly, it provides a space for reflecting on key issues of concern to the practitioners and service users (Noble & Irwin, 2009).

To be effective, practitioners, supervisors, and supervisees must be open to explore a range of conversations, activities, interactions, events, political debates, and organisational behaviours that occur outside the practice domain, particularly those events that impact directly on service users circumstances and opportunities and the broader social work mission as well as those of their immediate practice context. It means that social workers be open to critically reflect on the ‘web of connections’ that are in play in the lives of service users, the organisations that interact with them and the politics that resource them (Morley et al., 2014; Noble et al., 2016).

Embedded in a working and helping relationship social work supervision provides a safe and supportive space to assist in the maintenance of hopeful, positive practice (Beddoe & Davys, 2016). An even stronger theme that emerges from the progressive debate is that supervision should promote ‘deep’ learning and critical reflection in preference to providing support, guidance, and professional survival (Noble et al., 2016; Smith, 2011). Its practice should never be reduced to professional surveillance and supporting conservative polices linked to (austere) welfare reform but as a means for practitioners to fulfil their critical mission to promote social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people (Hair, 2015, IASSW Global definition, 2014). The supervisors and supervisees who form the supervision relationship are often from the same discipline who share common ethics, values, norms and professional goals, which can help foster a critical dialogue and response (Hair, 2015; Noble & Irwin, 2009).

Critical Supervision—Foundations

A critical approach to social work supervision is to steep the practice and process in critical theory and seek its application so that practitioners and service users can reflect on their circumstances broadly as well as personally. The reflection is to find a path towards a resistance and a change in their circumstances in a way that will enhance their well-being and create a more democratic and equitable social order. It acknowledges that people who are oppressed are subject to unjust systems that do not distribute society’s benefits and opportunities equitably (Noble et al., 2016).

Critical supervision is informed by critical theory. Several critically informed options already exist that can inform a critical lens. These include structural and post-structural theory, feminism, social constructionism, constructivism, post-modernism, post-colonial theory and critical multiculturalism, post-conventional social work, new materialism and post-humanism (see Noble et al., 2016, pp. 117–123). Its focus is on understanding broader structural factors impacting on organizations, service users, practitioners, situations, and events. ‘Using critical perspectives enables a view of the broader contexts in which organizations function, service users live, and practitioners do their work and the interplay within and among them’ (Noble et al., 2016, p. 145). It also maps out a world view and the many facets comprising the socio-political and cultural and economic power plays influencing the broader structural context as well as organizational and professional contexts.

So how could social work supervision assist practitioners link critical theory with a critical practice and what skills and strategies would be useful in this endeavour? Importantly, what would supervision look like if we were to place service users their experiences, values, interests, ideas, and perspectives in the centre of the reflection. That is, what would its pedagogical practice entail? A key tool to get to the hidden context and influences is to engage in critical supervision within a critically informed pedagogy (also see Fook & Gardner, 2007; Smith, 2011).

Critical Supervision and Transformative Learning

Giroux (2011) and Brookfield (2005) as critical educationalists see education as a site of participatory democracy, civil activism, and social change. Knowledge production through learning and reflection has a social purpose. The purpose is to further social justice, keep democracy alive, and citizens engaged in securing their well-being. Its broad aim is to educate practitioners to question the “conditions giving rise to oppression, discrimination, human rights violations and social injustice, yet remain open to diverse perspectives, understandings and forms of knowledge to suit different purposes” (Noble et al., 2016, p. 130).

Critical supervision as a practice pursues social justice outcomes. It seeks anti-oppressive and culturally sensitive ways to review practice processes, context, and responses. The outcome is to create critical practitioners and the best interests of service users who bear the brunt of an oppressive capitalist social and economic system (Hair, 2015; Noble et al., 2016). A critical perspective is about seeing a bigger picture, naming the broader political, social, economic, cultural, environmental, technological factors shaping the immediate practice environment.

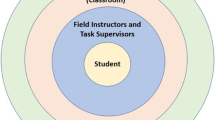

To undertake this process shifts the analysis from an individual view of social issues and solutions to the broader societal factors that shape the personal and professional lives of social workers and service users. It creates an openness to focus on social change and social justice outcomes. One aspect of critical supervision is to see individuals, families, groups, and communities as embedded within networks of social, political, economic, and cultural relations or webs of connection. Figure 51.1 sets out the parameters visually.

Web of connection in critical practice and supervision (Noble et al., 2016, p. 148)

Critical supervision facilitates an openness by encouraging practitioners to revisit critical theory, explore new ideas, seek out underlying assumptions and motives as well as encouraging questioning of routinised, superficial knee-jerk responses to complex social problems (Noble et al., 2016, p. 131). It is transformative when a new perspective emerges from a critical rethinking of prior interpretations, biases, and assumptions to form new meanings to understand the world and our experiences in it. By reformulating prior knowledge and the meanings and practices attached to it; by critically reviewing the dominant view of practice, policy and socio-political discourses it is possible to emerge from this process as an autonomous, critically focused practitioner (op. cit., p. 138).

Fundamentally, critical supervision is formed through conversations, that are thoughtful, reflective, and use an array of strategic processes, tools, techniques, and skills. Without the appropriate skills and tools linked to an understanding of critical theory and used in a particular way, a critical approach to supervision may stand or fall in its desire to develop critically informed and active practitioners.

Critical Pedagogy

Critical pedagogy is a teaching approach informed by critical and other radical and post-conventional theories and practices which helps practitioners and service users critique and challenge the oppressive structures of the status quo. It is a pedagogy that equips supervisors with the necessary knowledge, skills, and ability for critical thinking, critical reflection, and critical practice. It requires that a critical lens is placed on all practice and organisational interactions from the local to the global; from the individual to the structural. Its practice incorporates constant questioning and reflection and ongoing dialogue and critique of, the socio-political, economic and cultural power relations within the organisation as well as more broadly in the community and society at large (Fook & Gardner, 2007; Noble et al., 2016).

By applying a critical lens to the work and process of supervision practitioners as well as teachers can explore a critically reflective view of the socio-political landscape to support social works’ social justice and human rights agenda for societal and individual empowerment as well as its work, interactions, and practice outcomes. A critical pedagogy offers a framework for critical supervision to support the development of critical practitioners to untangle these webs in such a way as to free practitioners and service users from the political, economic, social, cultural, and organisational restraints that limit opportunities for a good life. Critical supervision sees the learning opportunities from this interaction as having a performing and empowering, transformative and emancipatory function (Freire, 1972; Noble et al., 2016; Noble & Irwin, 2009).

It is the position of marginalization that becomes the source of resistance, hope, and focus for supervision. It is the deliberate exploration of stories, collective histories, sense of community, culture, language, and social practices that become the source of power and resistance (Brookfield, 2005; Freire, 1972; Smith, 2011). This is true when reflecting on organizational behaviour as well as interacting with service users. A critical perspective is about questions, reflection, questions, reflection, questions, and so on. Critically informed questions shape the basis of critical pedagogies and encourage open and inclusive dialogues to “help those who seek greater control over their lives to envisage ways to achieve a better future” (Noble et al., 2016, p. 129).

Critical pedagogies seek to:

-

Engage in forms of reasoning that challenge dominant ideologies and question the socio-cultural and political-economic order maintaining oppression

-

Interpret experiences of marginalisation and oppression in ways that emphases our relational connections to others and the need for solidarity and collective organisation to others

-

Unmask the unequal flow of power in our lives and communities

-

Understand hegemony and our complicity in its continued existence

-

Contest the all-pervasive effect of oppressive ideologies

-

Recognise when an embrace of alternative views might support the status quo it appears to be challenging

-

Embrace, accept and exercise whatever freedoms they have to change the world

-

Participate in democracy despite its contradictions (adapted from Giroux 2011; Brookfield 2005 in Noble et al., 2016, p. 129).

The emphasis on using critical pedagogies in supervision assumes that professional supervision is a significant place for learning, review, reflection, and social change. It seeks to open up new avenues for exploration and through a process Carroll (2010) calls ‘transformational openness’ where we can create ‘shifts in mentality’ for new voices, perspectives, and understandings to emerge. Models are useful but without appropriate tools and skills used in a particular way and towards a particular end it may not achieve their intention. Indeed, supervision that is unreflective and unchallenging may just support the conservative and NPM status quo. Critical supervision is aimed at developing critically informed and critically active practitioners from a process of learning. This process must be informed by a critical lens.

Linked to critical analysis critical pedagogies are used to draw out our thinking, assumptions, use of language, power relations, biases, prejudices, conflicts, resistances, and beliefs. By placing our practice under a microscope, we open up previously closed spaces to make way for new practice approaches in supervision—practices that help practitioners as well as service users free themselves from oppressive daily habits and customs to create a ‘big picture’ interaction; one that sees and challenges existing power relations and structure that oppress, marginalise, and discriminate in order to promote human rights and social justice and empowerment outcomes (Hair, 2015; Noble et al., 2016).

Pedagogical Skills and Tools

Here, I identify six pedagogical skills and strategies that will help in establishing a critical narrative for use in professional supervision. These include the use of critical questions; critical thinking; critical analysis critical reading; critical reflection, and finally modelling critical practice.

Critical questions can encourage deep, sustained, reflective discussions. Open-ended questions can generate new thinking and dialogue as well as reflection and can move the conversations forward. Questions that link to prior discussions can lead to deeper reflection. Hypothetical, cause and effect questions, summary and synthesis questions and challenging questions are all part of the repertoire available for use. Examples include

Me and my supervision

-

What do you think a ‘transformative supervisor’ might look, sound, and feel like?

-

How do I feel about being supervised by a ‘transformative supervisor’?

-

How do you feel about being a transformative supervisor/supervisee?

-

What feedback might you invite from service users to enable your practice to be a medium in which all parties might shift perspectives, learn, and grow?

Supervision

-

What previous experiences informed your/my decisions/actions?

-

What knowledge did you draw on? Explore source, author, date, context, etc.

-

What particular theory or theories did you use?

-

What values guided your decision/action?

-

How did you feel?

-

What does this mean? To you, the service user, others involved?

-

What were the consequences of your decision/action??

-

Who benefitted from your actions and how?

-

Who was disadvantaged by your actions and how?

-

Were there alternatives and, if so, what are they?

-

Were there any constraints on your action, e.g., time, resources, agency policy, agency culture, and your own skills?

-

What, if anything, would you do differently next time?

-

Was there a desired outcome which was different from the actual outcome? (see Fook & Gardner, 2007; Noble et al., 2016; Noble & Irwin, 2009)

Critical thinking signals a willingness to open our actions and motivations to scrutiny to enable fresh perspectives and understandings to emerge and help form new learning and perspectives. Underpinned by a sense of curiosity and discovery, critical thinking uses analysis to examine in detail what happened and its consequences. Critical thinkers challenge values, ethics, assumptions, beliefs, theories, and practice knowledge to assess the veracity of information, research, and knowledge form diverse sources (Noble et al., 2016, p. 109). For example, it espouses differences between facts and values; between assumptions and assertions, between arguments and actions. Discerning their differences and exploring the impact can create critical conversations, reduce error in assumptions, and identify difference between facts and biases. Some reflection exercises when reviewing practice include;

-

What assertions, assumptions and biases are implicit and explicit in my analysis and action?

-

Where do these assumptions and biases originate from?

-

Is there another way to approach the situation or problem?

-

Was my judgement fair and balanced? Is it defensible?

-

Are the facts accurate?

-

What are the dominant discourses at play here?

-

Did I exercise enough curiosity and scepticism while examining them?

-

What are alternative responses? and have I explored them fully?

-

What was useful, helpful, affirming in what happened?

-

Has my thinking changed after this analysis? How? (also see Brookfield, 2005)

Critical analysis seeks to identify the structural factors leading to social inequalities and multiple oppressions in society. It involves breaking down those structures that are seen as harmful divisions with a view of overcoming them for a more equal and just society (Baines 2011). Its strategic analysis seeks to expose vested interests, power monopolies, inherited and ‘white’ privilege, gender, age and ability bias, elitist practices and unjust redistribution of resources and uneven access to knowledge sources (Baines, 2011; Lundy, 2011). Again Freire’s (1972) thesis on how ‘education for the oppress’ can be a tool for empowerment and social change is still an influential guide to transformative practice. In critiquing the existing social, political, and cultural arrangements it is hoped something better will be achieved. Critical analysis is informed by structural analysis steeped in social justice and human rights tradition (Ife, 2012).

Critical reading can be useful in going over case notes, reviewing research studies, literature, book chapters, journal articles, policy documents, media stories and agency and ethical guidelines. ‘Critical reading of our knowledge base enhances understanding, improves thinking, expands horizons and reveals a whole new world of thought and imagining’ (Noble et al., 2016, p. 192). It highlights ambiguities, inconsistencies, incoherencies, different cultural and gender basis and the appreciation of these complexities in practice and knowledge construction (Brookfield, 2005). For example, by examining a text for contradictions, biases, unsupported assumptions, social practices and language that oppress others we have the ability to uncover and expose perspectives and interpretations that need challenging, exposing, and repositioning (Fook & Gardner, 2007; Smith, 2011).

Critical reflection places emphasis and importance on uncovering values, assumptions, biases, and how and why power relations and structures of domination are created and maintained and who benefits. According to Fook and Gardner (2007) ‘a critical reflective approach holds the potential for emancipatory practice in that it first questions and then disrupts dominant structures and relations and lays the ground for (social) change’ (p. 47). Questions focusing on reflection include:

-

What are some of the key messages in this text?

-

Who is the intended audience?

-

What words, language, and statements do you see and hear?

-

What are their meanings? and what are the underlying assumptions?

-

Whose knowledge is privileged? How?

-

What power relations can be identified? To what end?

-

What strategies are available for challenging knowledge construction?

Modelling critical practice is about leading with action not words! Supervisors should model critical practice in various supervisory events. They should demonstrate the appropriate use of questions and encourage deep learning and reflection. In modelling a critical practice, supervisors can play an important role in creating and fostering a learning culture in their organisation—a culture that values knowledge, supports learning, and fosters worker expertise. Critical supervisors are also critical practitioners. The key intention in creating a critical perspective for use in supervision is to develop practitioners’ ability to counteract the socio-political and cultural constraints currently influencing a more conservative practice—that is to promote a social justice, anti-oppressive informed practice (Baines, 2011). Figure 51.2 outlines the process diagrammatically for a clear statement of how a critical approach for use in professional supervision can unfold.

A critical supervision and practice process (Noble et al., 2016, p. 152)

Conclusion

In this chapter, I have outlined key elements for supporting critical supervision and practice. It goes without saying that this process is complex and challenging and requires time, trust, commitment, and professional space to dig deeply into the way power relations and unjust social practices oppress practitioners and service users equally. If practiced with a critical lens professional supervision can provide an opportunity for both supervisor and supervisee to reflect on ways to disengage from oppressive structures with the aim of empowering social work practice and service users alike.

In the current context of neo-conservative politics and NPM discourse professional supervision may be the only available forum to reflect on practice, research and to explore and experiment new sites of resistance and social change. Its use in supervision has the potential to open up discussions and interaction beyond what is known to spaces where new knowledge, theory, practice options, and broader societal concerns are explored. It encourages ‘deep learning’ that can shepherd a transformational opportunity for new learning. Indeed, nothing begets learning that stimulates curiosity and the desire to learn more when a good supervisor and eager learner meet in a supervisory relationship with an ultimate end to achieve justice for all.

References

Baines, D. (2011). Doing anti-oppressive practice: Social justice social work. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Press.

Baines, D. (2013). Unions in the non-profit social services sector. In S. Ross & L. Savage (Eds.), Public sector unions in the age of austerity. Halifax, NS: Fernwood Publishing.

Beddoe, L., & Davys, A. (2016). Challenges in professional supervision. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Brookfield, S. (2005). The power of critical theory: Liberating adult learning and teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Carroll, M. (2010). Supervision: Critical reflection for transformational learning (Part 2). The Critical Supervisor, 29(1), 1–19.

Chenoweth, L., & McAuliffe, D. (2015). The road to social work and human service practice (4th ed.). South Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Cengage Learning.

Fook, J., & Gardner, F. (2007). Practicing critical reflection: A resource handbook. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Giroux, H. (2011). On critical pedagogy. New York: Continuum.

Gray, M., & Webb, S. (Eds.). (2013). Social work theories and methods. UK: Sage Publications.

Gray, M., & Webb, S. (Eds.). (2016). The new politics of social work. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hair, H. J. (2015). Supervision conservations about social justice and social work practice. Administration in Social Work., 15(4), 349–370.

Hughes, M., & Wearing, M. (2013). Organisations and management in social work. London: Sage.

IASSW Global definition of social work. (2014). https://www.iassw-aiets.org/global-definition-of-social-work-review-of-the-global-definition/.

Ife, J. (2012). Human rights and social work: Towards rights-based practice. GB: Cambridge University Press.

Ife, J. (2013). Community development in an uncertain world: Visions, analysis and practice. Port Melbourne, VIC: Cambridge University Press.

Jamrozik, A. (2009). Social policy in the post welfare state: Australian society in a changing world (3rd ed.). Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Education Australia.

Lundy, L. (2011). Social work, social justice and human rights: A structural approach to practice. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Mendes, P. (2017). The Australian welfare state system. In C. Aspalter. (Ed.), The Routledge international handbook to welfare state systems Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Morley, C., Macfarlane, S., & Ablett, P. (2014). Engaging with social work: A critical introduction. North Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

Noble, C. (2007). Social work, collective action and social movements. In L. Dominelli (Ed.), Revitalising communities in a globalising world. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Noble, C., Gray, M., & Johnston, L. (2016). Critical supervision for the human services: A socialmodel to promote learning and value-based practice. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Noble, C., & Irwin, J. (2009). Social work supervision: An exploration of the current challenges in a rapidly changing social, economic and political environment. Journal of Social Work, 9(3), 345–358.

Smith, E. (2011). Teaching critical reflection. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(2), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.515022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Noble, C. (2020). Critical Pedagogy and Social Work Supervision. In: S.M., S., Baikady, R., Sheng-Li, C., Sakaguchi, H. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Global Social Work Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39966-5_51

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39966-5_51

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-39965-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-39966-5

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)