Abstract

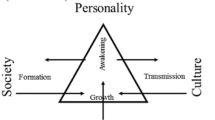

This chapter presents an account of a practice-focused research study conducted in an Arts Education college in England. Narrative inquiry (Clandinnin and Connelly, Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2004) informed both the methodology and the collection and analyse the data. The study explores direct experiences using story, critical dialogue and narrative inquiry in a Community of Enquiry (Lipman, Thinking in Education (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003). The intent is to encourage students of the Arts to think critically and creatively, improving their motivation to read and write about the Arts. A secondary aim of the study is to explore the formation and identity of the artist. The study is essentially an attempt to fuse horizons of educational research and practice (Scott and Usher, Understanding Educational Research. London: Routledge, 1996, pp. 21–22) through practice-focused research. It reports the findings of two pedagogical interventions. The first intervention, designed as a Diary Project, asked students to keep a diary of their experiences of the critical thinking interventions used in the study and to reflect upon and present an account of these experiences, including any changes in their ways of thinking, as they engaged in critical thinking interventions. The second intervention took the form of a Book Club where students, lecturers, and other education practitioners met each week to discuss narrative accounts of the lives of artists. An overarching Community of Enquiry (Lipman, Thinking in Education (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003) was used to structure and facilitate critical dialogue across the interventions.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- FE pedagogy

- Critical thinking

- Practice-focused research

- Narrative inquiry

- Community of inquiry

- Arts education

Introduction

Brown (1998, p. 189) states that the idea of educating students in an atmosphere of equality and joint inquiry could maximise each student’s access to the legacy of the critical traditions might at first appear to be a high risk strategy. He goes further describing critical the introduction of thinking interventions in education as an invitation to classroom disorder. Positive, creative, fruitful disorder is what I was hoping for when I embarked on this research journey. Close reading of the ideas of Lipman (2003) reveals that he turns his back on confrontational, rote, shame based teaching and instead advocates, telling stories to each other. Lipman observes that the education system can sometimes operate as a machine to create ‘biddable’ citizens who cannot think for themselves. Some of the Access students I teach have had a rough ride through education, and silent resistance with a set face is a polite version of the strong emotions their educational past brings up. Brown and Lipman offer us a soft skills alternative approach to teaching critical thinking (CT) which has a radical undertone. Art education in its best form allows for experimentation, unpicking past knowledge and remaking it with surprising new elements. Access students readily came to lunch time experimental critical thinking interventions involved in the research. They understand the value of social and cultural capital, and they do not want to be left out of the big conversations any more. Reading and adapting Brown and Lipman’s ideas, I developed Community of Inquiry interventions with my students Some students found critical thinking interventions moving, vocabulary expanding, healing, new horizon finding and (form them) authentic and ‘true’.

This chapter describes the nature of the educational issue which provided the impetus for this study and the context in which it occurred. It then discusses issues surrounding the development of critical thinking in educational contexts. It considers the works of key contributors to the debate concerning issues of whether critical thinking can be taught or whether conditions can only be created in which critical thinking can develop and flourish. It then presents, analyses and discusses illustrative examples of empirical data collected from the study’s participants. This chapter reports different perspectives of practitioners of the Arts, educational theorists, Arts educators and students regarding the development of critical thinking.

Definitions, problems, and issues in the development of critical thinking are considered in some depth. The stories of students of the Arts and those of their lecturers and other education practitioners regarding their experiences of engaging in the pedagogical interventions in the study are presented and discussed. This chapter also provides accounts of participants’ experiences in the study in relation to the development of their identity as artists. The chapter concludes by drawing attention to the ways in which pedagogy in the FE sector has become overly concerned with the acquisition of narrow learning ‘outcomes’ and preoccupations with highly prescriptive curricula, to the detriment of considerations of enduring educational issues and the development of more creative pedagogical approaches potentially capable of encouraging students to think critically, creatively and for themselves (Lipman 2003).

The Research Problem

Vocational students (particularly students of the Arts) often find it difficult to engage with theory. On the other hand, the same students often find practice to be enjoyable instinctive and fulfilling. Baldisserra (2020) draws attention to the resistance and frustration felt by many vocational students who are intent on engaging in thinking through making by creating artefacts and objects of art by hand. At the same time, students of the Arts are also required to think and write in order to demonstrate competence in their chosen vocational area and to meet the requirements of their course.

I work with intelligent, committed, and enthusiastic students who nonetheless feel inhibited in their learning by at least some of the assessment methods currently employed to capture their creative and critical achievements. On the face of it, this phenomenon could be seen to support the existence of Cartesian mind-body duality deriving from a nineteenth century rationalist philosophical world-view (see Chaps. 1 and 11) in which theory and practice are regarded as being separate or diametrically opposed (Carr 1998; Merleau-Ponty 1945). However, while intuitively appealing, taking arbitrary divisions and dichotomies in education at face value may in the long run prove to be unhelpful. Hyland (2017) points to the creation of a vocational and academic divide, a further dichotomy whose roots he detects in the social and political structures of ancient Greece where vocational education was regarded as subordinate to ‘intellectual’ pursuits.

Broad (2013), Gregson et al. (2015b) and Lavender (2015) draw attention to the importance of recognising that the value of learning of all human beings. They argue that the needs of vocational students are as important as those in any other sector of education or from any other walk of life. Hyland’s (2017) underscores the importance of this. He argues that any ranking between vocational education and academic education needs to be reconsidered in light of an affirmation that vocationalism is useful and meaningful. He notes Aristotelian intrinsic goods in vocational education and states how these should be valued as highly as those found in academic education. Dewey (1934, p. 236) concurs with Hyland (2017) controversially stating that all ranking of higher and lower when it comes to a Cartesian mind/body split, or vocational versus academic, are ‘out of place and stupid’. According to Dewey, each medium, craft, or discipline has its own efficacy and value. Kant (in Gregor and Denis 2017) notes that the concept of a rationally guided Will adds a moral dimension to human action and he argues it is this recognition, together with an appreciation of duty itself, that must drive our actions. Research in the field of critical thinking also fuels the debate between vocational and academic education. These competing perspectives are compared, contrasted and discussed in some detail in the literature review section of this chapter.

Context of the Research

The FE Art course which I teach has both practical art and theoretical contextual studies elements. This conflation causes a problem. Students come to art school because they are practically interested in making art. The same can be said for their lecturers (Baldissera 2020; Barrett and Bolt 2007). However, many students are indisposed and resistant to writing and reflection (Lavender 2015) and reluctant to commit themselves and their thoughts to paper (McNicholas 2012). Furthermore, many lecturers say they simply do not have time to provide extra tuition and support. An informal interview with FE lecturers Roma, Lupe and Jupiter in the data analysis section of this chapter highlights this issue.

Research Population

The research population for the Diary Project is made up of 26 participants from the art college: 18 students, 6 lecturers, 1 technician and a student’s husband. The project lasted for 12 weeks. Throughout the research, I also kept ongoing reflective field notes in the form of a research diary. Participants completed their diaries at home in their own time. There are 28 participants in the Book Club intervention, 23 students and 5 lecturers. This intervention lasts for 6 months and is held weekly at lunch time where the participants can discuss a chapter from a selection of books on artists in an informal learning atmosphere. Interviews were also set up as part of the study to capture the student and teacher voice, identity development, and gauge experience of engagement in the pedagogical interventions. Each intervention is informed by literature from the field of critical thinking with the aim of improving and developing students’ capacities for, and willingness to engage in critical thinking. Literature informing the study includes the works of Brown (1998) and Lipman (2003), together with literature and research regarding the development of professional identity Biesta (2014), Broad (2013). This chapter captures perceptions of experiences the Book Club and Diary Project. Research methods in this small-scale, qualitative, ethnographic study include observations, recorded field notes, analysis of students’ written notes from Book Club and Dairy Projects and images and artefacts created by the students reflecting their experiences of these interventions. The techniques of thematic analysis are employed to illuminate and analyse data.

Debates and Issues in the Teaching of Critical Thinking

In the past, the study of Education has been variously located in the fields of Philosophy, Liberal Studies or General Studies. The term ‘critical thinking’ in relation to discussions of the nature of thinking was used first by Dewey (1933) and then in the 1960s as a component of Bloom’s Taxonomy (Bloom et al. 1956). Through the late 1970s the Critical Thinking Movement, headed up by Elder and Paul (2018), emerged. Their framework of Intellectual Traits was tentatively taken up in the 1980s and 1990s as part of UK educational policy but soon came to be marginalized or dropped from curricula. In current policy (DfE 2016, 2018; UNESCO 2015) critical thinking is only referred opaquely, without overt references to peer-reviewed literature and research. In an alternate point of view McPeck (1981, in Hitchcock 2018) attacks the Critical Thinking Movement for its over generalisation. Brown (1998) illustrates how critical thinking must be understood in historical and philosophical terms [as a] recognition of an individual right of enquiry and criticism which has clear democratic and libertarian implications. Brown (1998) advocates teaching critical thinking but reminds us how, in his opinion, it is specificity that is all important. Lipman (2003) emphasizes the importance of experiential critical thinking, introducing the reader to the educational philosophies through the linguistics of Vygotsky (1989) and the epistemology of Piaget (1973). Lipman (2003) claims that it is essential to teach reasoning and argumentative skills to children. He argues this can be accomplished through his programme of Philosophy for Children (P4C). There is a genuine concern in Lipman’s work for the betterment of students. His central message is that didactic styles of teaching are not positive, and that confrontational education does not work. He goes on to argue that children are not learning because they are not learning to think / taught to think (Coalduca 2008).

The Right to Learn

Plato (428–347 BC), philosophised about the relationship between the individual and society and believed that education is a basic component of a good society. His thinking led to a vision of an ideal city or Republic, and an imagined social world with a tripartite education system. Citizens would be trained or taught from childhood within the bounds of their class. The UK school system used this Platonic triple streaming in post World War II. Some would argue that despite rhetoric to the contrary, this is how state schooling still operates today. Dystopian novels often use this trope to set up a system for the hero or heroine to rebel against.

Lipman (2003) supports the promotion of practice and experience-based thought and learning. If this theory were married to the utilitarianism of Mill (1859 in Philip and Rosen 2015) and the equality, freedom to learn and rights of education for all of Freire (1968), could go a long way to augment the State Educational programmes in the UK. Brown (1998) paraphrases On Liberty (Mill 1859), saying that the ‘rote’ learner whether it be a child or an FE student, is a microcosm of the ‘servile society’. This is reminiscent of Lipman’s concerns about education creating ‘biddable citizens’. For Lipman, learning appears to be inhibited because insufficient attention is being paid the development of critical thinking. Making a similar point, Brown observes that thought and action are ‘embalmed’ in superficiality and contradiction. Both Lipman and Brown are looking for a way to defrost the embalming process and its genesis in rote learning. Both note how little access or recourse to philosophy, debate and critical thinking students have in the current state systems of education in the UK and the USA.

Can Critical Thinking be Taught?

As a teacher I like to think that anything can be taught. It is however unhelpful to think of critical thinking skills in the same way that ‘special’ skills just as grammar or correct wiring can be learnt. Learning any skill to a high standard takes a great deal of time, effort, repetition and sacrifice (Sennett 2008). If Art and critical thinking are skills to be mastered the question is then becomes why cannot critical thinking in an arts context be honed in the same way that other skills are crafted and honed?

Against Generalization

Brown (1998) and McPeck (1981) say that critical thinking can be taught but not in a general way. They argue that critical thinking needs specificity. Brown (1998) and Oakeshott (2015) both point out that ideas about ‘exfoliating’ and rejecting generalization lead to the assertion that critical thinking cannot be vaguely channelled into what they assert as meaningless ‘transferable skills’. The specificity imperative is also echoed in Mitchell et al. (2017), who talk about critical thinking as being extremely specific. They believe critical thinking is contracted and negotiated between educators and students; it is a collaborative activity tailored to a particular pedagogic situation.

In this research lecturers, technicians, and FE students are both collaborators and participants. The futures of these FE students can be visualised in a geographic walk from our FE site, up the hill to the HE building. HE is a mapped upward ascent, mirroring student aspiration. The measurement may not come this year or next but maybe in five or seven years after graduation at undergraduate or postgraduate levels.

For Disciplinary Specificity: Brown’s Narrative

The concepts of intentionality, expectation and diverse standards make critical thinking a Herculean task to pin it down. Brown states that, worryingly, school leavers are showing a ‘thinking skills deficit’. Lipman (2003) wants to span the gap of this thinking skills shortfall. He corroborates the philosophies of Aristotle and Hyland (2017) extolling the virtue of teaching. He wants to wake students up to critical thinking and philosophy as a way of rousing minds to life, making the world more creatively potent.

McPeck (1981) believes that empirical subject-specificity raises the general problem of transferability. He argues that each subject must develop its own version of critical thinking. Once this is achieved what happens to critical thinking in everyday life problems and issues, or societal and governmental difficulties; how can critical thinking solve those? Proponents such as Brown (1998) and McPeck (1981) emphasise that transferability is more likely to occur if there is critical thinking instruction in a variety of subject areas, with explicit attention to dispositions and abilities (the transferable skills) that cut across FE sectors of teaching and education. In a previous pilot study I discovered that the separating of disciplines into ever narrower areas and silos is detrimental for the students and their learning. In an interview conducted for that research study it was found that FE students desired collaboration and interdisciplinarity: one participant reported the benefits of ‘working with old skills’ and in the ‘multiplatform context of a collaborative, creative multi-skill community’.

Brown’s specificity may not always be the answer. This raises the question as to whether generality always needs to be seen in opposition to or ‘versus’ specificity? Perhaps generality and specificity need not be binary or regarded as polar opposites of each other.

Transferability of Critical Thinking Skills

McPeck (1981) deems it is unsuccessful in education to teach critical thinking as if it were a separate subject. He insists that practitioners should guide their students to autonomous thinking by teaching in such a way that develops cognitive structure, discussion and argument. That critical thinking is specific is also contested by Sennett (2008) who points to the 10,000 hours of practice and repetition that it takes to develop mastery of a craft. The muscle memory of craft Sennett argues, lends itself easily to a different discipline that still involves using the eye, the judgement, sensibilities, and the hand. Hyland (2017) posits an example of less transferable skills, such as someone who inputs data into a computer being asked to engage in highly vocational occupations. Brown (1998) advises that early repetitive memorizing creates a foundation from which to start to think critically. FE students engaging in the acquisition of hairdressing, electronic engineering, or Art practice must start with emulation and mindful repetition. As Sennett says in his book The Craftsman (2008), the path to mastery has stages, and right at the beginning these stages involve learning to observe, to watch, to look, notice and to absorb. Then to imitate and to emulate. Finally it is the practice, and repetition, the 100,000 hours Sennett (2008) required for a practitioner to become proficient that leads to the modification, extension and transcendence of a practice from one tradition or form of life to another.

Lipman

Lipman (2003) proposes that conducive conditions for critical thinking can be created by teachers but that critical thinking cannot actually be taught. He judges that critical thinking must be practiced or experienced in tacit, experiential learning. This would echo the Aristotelian notion of phronesis, or practical wisdom advocated by Broadhead and Gregson (2018). However Elder and Paul (2018) have written books on how to teach critical thinking and are in no doubt that it is not only teachable but also successfully learn-able. Lipman (2003) is adamant that critical thinking also needs creative thinking.

Critical Thinking Toolkits

Critical thinking toolkits and tips for teachers are to be found on many college library shelves. It is important to view works of this kind though a highly critical lens. What appears to be a crucial toolkit for one teacher may not be relevant or be completely out of context for another. Elder and Paul (2010) have devised the Intellectual traits a framework by which to judge whether thinking is critical. They also introduce six stages of critical thinking, from Stage One: The Unreflective Thinker, to Stage Six: The Accomplished Thinker, and explanations of how each category may be understood for critical thinkers. While De Bono (1974) (among others) devises games, strategies and propositions to develop lateral thinking.

Critical Thinking, Critical Making

Broadhead and Gregson (2018), supported by Hyland (2017) have found through teaching experience and research that technical-rational world views have many shortcomings. They offer an alternative understanding of the world rooted in Dewey’s Pragmatic Epistemology which is informed by Aristotle’s understanding of practical wisdom. Hyland (2017) and Dunne (2005) challenge the primacy technical-rational reasoning. Somerson and Hermano (2013) show that critical thinking is at the heart of their practical curriculum in Rhode Island, say that students are immersed in a culture where making, questions, ideas, and objects, using and inventing materials, and activating experience all serve to define a form of critical thinking albeit with one’s hands. They call this critical making.

Transformation Through Narrative Inquiry

Gregory (2009) and Rogers (1994) discuss the changes educational stories and narrative inquiry can make on educators and FE students. Transformation has a lot to do with Mezirow’s idea (1991) that adult learners break out from ‘habitual action’ giving themselves permission to change, do something new. The transformation of class, gender stereotypes and life experiences can come into being through a strong sense of connection and identity. Data from this study suggests that this in some way has been facilitated and supported through the Book Club and the Diary Project, by meeting, sharing, talking, planning and becoming inspired by each other’s aspirations and stories.

Data Analysis

Pedagogical Intervention 1: Diary Project

Diaries have been used successfully in the past by Schönn (1991) which he calls reflection in action. Shulman (1989) in Sá (1996) describes diary writing as an important data source. Burke (2001, p. 9) adds a feminist framing and ‘auto/biographical’ elements to her Diary Project for Access students, using her own story as a starting point. The diary writers had no teaching or input, no parameters, did this increase writing skills? I was hoping to find out that that CT and skills in written and spoken English were developed through the practice of diary writing. A daily practice of setting down thoughts and reflections to increase criticality. Diary writing offers an approach for staging and conducting creative arts research, to situate art studio enquiry more firmly within the broader knowledge and cultural arena. The diary could be a work of fiction revealing underlying emotive, heartfelt beliefs about art, practice, and self-reflection of the participant. Criticism is that diaries could lead to unproductive introspection or overly descriptive entries, participants could get bored and their enthusiasm trails off leaving no entries at all in the latter days of the project. Data from thus study produced mixed findings from the Dairy Project intervention.

Artemis course leader of Access to HE used the diary in quite a formal way, making his reflections factual, and planning notes and used that space as a place to work out detailed schemes of work. Conversely Gaia, course tutor on Foundation Art and Design (FAD) observes herself as a practitioner, ‘becoming more confident in judgement and perceptive about where students are going wrong or what they need to consider’ including the development of her own capacity for the exercise of wise judgement through teaching practice and the reflective process.

Another aspect of practitioner identity is evident in Lupe’s narrative, a Pathway Leader on FAD, she expresses that she feels more comfortable as a team player (not being singled out) and often suffers from ‘imposter syndrome’, low self-esteem and class anxiety. Instances of practitioners in the study feeling like a fake or a fraud are documented and corroborated in, The Journal of Higher Education, article by Brems et al. (1994). Professional identity is not simple or straightforward and is often influenced by personal circumstance, past educational experiences both as a teacher and as a learner as well as in working contexts.

Research Project Interviews: Accidental Experts

Informal discussion in staff-rooms and interviews throughout the study repeatedly and regularly centred upon working with students and trying to find ways of encouraging the development of critical thinking in students. Examining the kinds of resistance practitioners come up against regularly and recognising that some of that hostility is actually something we as teachers struggle with too. This is a recurring theme in the data.

Roma, Lupe and Jupiter lecturers on FAD discuss the prevalence of dyslexia at art school, with the students and lecturers. Roma comments that she found reading ‘really frustrating’ and avoided it ‘I thought I was a moron’. Jupiter comments that ‘I have presumed students are neglectful or lazy when not keeping up with reflections [in their journal] but I’m doing the same thing.’ A study by the Royal College of Art (2015) states that twenty nine per cent of students identify as dyslexic. The theme of not having time also repeatedly recurred in the data. Roma states that some days it is ‘Hard slogging work,’ trying to see and speak to students in huge classes. She also talks about teacher guilt when students fail, ‘always asking if I could have done more?’ Lupe conjectures that ‘as a teacher you are passing on part of yourself’ and asks, ‘is being a supportive inspiring teacher just an ego dance?’

Issues such as, not having enough time to spend with students, or practicing our own vocational subject area were also repeatedly raised. Feeling pressure from the institution to complete paperwork, go to training and development sessions, away from family and being submitted to imperatives from outside college influences all served to make teaching a challenge. Staff in the study reported that the critical thinking issue as just ‘one more thing to add and we are already loaded with things to complete’. It was quite a task therefore to find volunteers who took the research project seriously were prepared to give it the time it needed. Coalter (2008), draws attention to the value of critical thinking in the classroom and the difference it can make to progression.

Eliahoo (2014) calls FE practitioners ‘accidental experts’, in her study she has found that very often their identity is with the actual subject they teach, they see themselves as an engineer, a hairdresser, a dental hygienist. Being a practitioner-lecturer seems to be a secondary identity. In a practitioner survey about critical thinking and professional identity devised in a previous study, eight lecturers and fourteen technicians responded. 92.31% of technician and 87.50% of lecturers identified as being an artist, designer or craftworker. So more technicians and instructor technicians see themselves first and foremost as an expert in their chosen field. A few less lecturers described themselves as art and design practitioners. Could this be that the dual role of practitioner and artist is difficult to maintain with the heavy load of administration and after teaching hours planning and paperwork? Surprisingly comparing the practicalities of being an artist and designer 100% of lecturer respondents said that the identity of being an artist was very important to them. A highly motivated group of lecturers who most clearly see that specification as artist is substantially significant to who they are. Conversely, when looking at the response to the question ‘Does teaching define you?’ it was a very mixed reaction. 37.50% replied yes teaching does define them. Positively associating as a pedagogue and embracing teacher status. However 62.50% replied that teaching does not define them. Leading to the conclusion that vocational lecturers much more strongly identify and their chosen professional subject rather than as a teacher. Eliahoo (2014, p. 19) corroborates this evidence stating that, ‘Those who taught in FE colleges were usually employed with professional and high level vocational qualifications.’ Despite this high level of expertise she goes on to state that 90% (Ofsted 2003) of FE practitioners did not have a teaching qualification at the point of employment, she goes on to acknowledge that, from her study, FE lecturers experience ‘dual professional identity’ at the start of their employment. That of being an expert and a learner a teacher and a student while they compete their in-service PGCE or PG certificate in education and training.

Pedagogical Intervention 2: Book Club

The Book Club is attended by lecturers and students. There is a flattened hierarchy here allowing for open dialectics (hooks 2007). This precedent is set on the first meeting when I read out my own educational story. One of misdiagnosed dyslexia, and being written off as non-academic and even special needs and starting my future art career colouring in with the dinner ladies, excused from formal classes with other children. This story connects with other students and practitioners who have a connection to my narrative and could find parallels in their own histories. My story gives permission and agency to the book club members, for students and lecturers to accept each other as equals in this particular situation and leads to an exploration through the personal stories along with the texts chosen to reflect life experiences of vocational students and teachers.

Change Theory from Mitchell et al. (2017, pp. 174–176) is applied to the Book Club. Participant stories of resistance and educational journeys are collected to build up a picture of collective experience. Book Club members listen to each other’s stories and coach each other with solutions to address resistance to writing and speaking. From interviews, students report increased confidence speaking in class and finding their voice. Duff (2018) has a particular perspective working with the Māori in New Zealand. ‘Instead of labelling them [students]…, we reach them with these narratives. When they hear the pūrākau (stories) you see a little spark in them.’ Māori creation stories are used as a form of healing, connecting alienated Māori to their whakapapa or their genealogy and culture. Perhaps participants by reading art texts and hearing about other’s educational journeys feel they are part of a Community of Inquiry. The group created a forum where political, economic, equality, diversity and inclusion discussions around the texts could develop and flow. Biesta and Goodson (2010) state that the interior conversations whereby a person defines their personal thoughts and courses of action and creates their own stories and life missions, is situated at the heart of a person’s map of learning and understanding of their place in the world. Coalter (2008) considers that social capital is used as a heuristic device to examine the mechanics of classroom activity, the bonding of the group and how the small world of an FE classroom relates to the larger networks of the workplace, the community and HE. Criticisms of the Book Club intervention could be that dominant members of the group might take over, speaking over everyone else. Varying the texts in an effort to interest all members could also alienate others in the group if they are not interested or feel they don’t have anything to say.

Discussion

Critical Thinking and Creative Thinking

Lucas and Spencer (2017) agree with Lipman (2003) and consider it natural for criticality and creativity to coexist. Lipman goes on to use the terms Creative and Caring when writing about critical thinking and adds that in addition to critical thinking students must also develop creative thinking and that the two elements of critical and creative go together to create holistic teaching experiences for students and lecturers. This is borne out in the experiences of the Book Club and the Diary Project. Each has grown into a Community of Inquiry where practice is developed in and through mutual engagement and dialogue (Fielding et al. 2005; Lipman 2003). Biesta (2014) and Dewey (1934) agree that critical thinking involves a conceptual investigation into problematic situations which disturb routine thinking and trigger a process of transaction where thinking occurs across the action in an attempt to understand the nature of the problem and potential responses to it. In this way problems begin to be unravelled through the research process, a process, which is itself a process of investigation.

Reflexivity and Measurability

For Socrates, a life unexamined is no life at all. This can equally apply to Aristotle’s concept of praxis which involves the development of practical knowledge and practical wisdom or phronesis. Baggini (2005) hints at academic elitism that leaves ‘unexamined’ the lives of 1000s of vocational practitioners of engineering, hairdressing, telephone operatives at call centres or teachers. Practice can be defined, reflected upon and captured in so many ways, not just the strict academic and scientific rules of measurement including highly questionable vanity metrics. Hairdressers may verbally analyse and make critical judgements of their last cut, which in FE we would call self-assessment and peer review with other students or with a tutor using speaking and listening. Mechanics working in pairs may collaborate, diagnosing and recommending solutions to complex mechanical problems, which Fielding et al. (2005) and Gregson et al. (2015b) would call collaborative working and Joint Practice Development (JPD).

Phronesis and professional judgement contribute to the development of art, the accumulation of experience, a judgement, getting your eye in, connoisseurship, expertise, deep physical knowledge, and knowing when it is enough, when it is just right, when to stop the process and how to avoid ruining a thing with overdoing it. In practice-focused research, the doing informs the thinking, or thinking through doing. In all of this, careful thinking is so important, it is the analysis of vocational subjects and the criticality of knowing. Asking, who else works like this? Contextualising professionalism with others in the same field. It is making choices and judgements to develop further. Making the teaching or electronic engineering more coherent, elegant, efficient and more inclusive. There is evidence from this study to illustrate the interconnectivity and inseparability of the two elements of thinking and doing in a non-dual, argument. Sennett (2008) reveals philosophical contexts for talking about the theoretical underpinnings of craft, vocation, professionalism, the intelligent hand and practice, whether it be carpentry, painting and decorating, computer science or graphic design.

Findings

Emerging findings from this research-in-progress are as follows:

Exploring practitioner story and identity through the two critical thinking pedagogical interventions employed in this study supplemented by a Community of Inquiry (Lipman and Sharp 1978) has been useful and illuminating to students and lecturers alike.

Both of these interventions provided lecturers, other practitioners and students with opportunities to intersect and interact in innovative and non-hierarchical ways.

The same interventions enabled story and personal narrative to inform and contribute to the formation and development of student identity through interpersonal connection and shared insights.

Through the Thinking Diary Project and Book Club, participants across the range of research participants, from students to practitioners and technicians found support and inspiration in published story texts as well as narrative accounts of their own experiences leading to aspirational long-term professional development. For example, Gaia applied for and is now in the first year of her MA. Roma seriously thinking about her future, post PGCE and planning in an MA either in education of art in the next few years. Artemis had the support and encouragement not to stall in his PhD and carry on to the end. Through the group work and discussions, Jupiter and Roma both had the courage to and achieved positions in HE as well as securing teaching positions in FE. Echo successfully completed her PGCE and has a teaching position at Gimmerton where she did her teaching practice and is planning to do an MA next year. Lupe after a period of uncertainty has gained a permanent contract and a teaching position in HE. Eos was almost cut from her team but through demonstration of commitment to the college as well as participating in the research project she was retained.

The central theme of the chapter asks, can critical thinking be taught or can we only create conditions to support its development?

Findings from this study also lend support to the claim that the same discursive aspects of all three interventions helped to create and sustain a sense of community and group identity.

Findings from this study also indicate that the pedagogical interventions employed in this study lend support to the claims that these approaches have contributed to enabling the students engaged in this study to think more critically, carefully and creatively about their engagement with their subject and their future as practitioners within it.

Data sets from this study suggests that using critical thinking skills to connect people and stories, and (Scott and Usher 1996, pp. 21–22) can fuse horizons between research and practice could prove to be an interesting way forward in the development of critical thinking skills in the arts and in other disciplines and subjects. Emerging findings are that critical thinking and be ignited with initial light touch teaching, in an informal teaching setting, with no learning outcome pressures or grades attached. As participant Skerrion states, ‘I think you can teach the structures of it [critical thinking] but is works best when there is spaces where people can do it in their own way.’ The theme is continued by Lamia when she says ‘I think once people understand what it [critical thinking] is, what it can do for them, then I think they can teach themselves.’ The most useful finding is that critical thinking once introduced by the facilitator develops through the practice of participants or students using critical thinking skills to interrogate a topic or creative project. Lamia again states, “I think it [critical thinking]… surely it unfolds if an opportunity presents itself. I think people have a knack for, you know, when they are talking with people, it is kind of something that just happens on its own. I don’t think you can teach it with a flow chart anyway. “wonderfully creative imagery expressed by Lamia of an unfolding, like a map and that the Book Club members have a knack of bringing out critical thinking in each other. It is by the doing of critical thinking, the practice of discussing, dialogics and thinking critically that critical skills are developed. Critical thinking needs an impetus and a structure to start it off in the minds of participants or students but essentially the best educators can do is create the conditions that support its development.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this small-scale qualitative ethnographic research study reports work-in-progress which is some respects runs counter to a trend which favours positivist methods and randomised control trials in the FE sector. A Department of Education report states,

There is a lack of evidence on how current practices operate to improve quality and improve learners’ outcomes. (Owen 2018, paragraph 6)

This research hopes to redress this trend towards positivist approaches … at least in some small part. The ‘softer’ aspects of these interventions described in this study may be viewed by some as being unreliable or ‘unscientific’ due to the interpretivist, and qualitative methodologies employed on the grounds that interventions analysed interpretively in a small-scale ethnography are not the same or of the same credence and value as hard statistics.

The Ethnographer Campbell- Galman (2013) and Burke (2001) an FE lecturer and researcher and Coffield (2008) an educational researcher of international standing, write about the messiness of educational research. Cultural art school practices especially are also ‘messy’ in contexts where too much system or structure is deemed suspicious and counter cultural. Critical thinking research in FE and art school is not neat and tidy. It is messy and non-conformist. It does not fit into clean categories, siloes or educational pigeonholes. It works in the interstitial negative spaces around the objects of teaching or not teaching. Lipman (2003) and Brown (1998) hold the view that some curricula have the intention to make ‘reasonable citizens’ biddable, compliant, un-argumentative students. Critical thinking aims to wake students up (Clarke et al. 2019) to rouse their minds to life. This involves infusing imagination, arousing curiosity and encouraging higher order thinking in students. This is an important ideal and a goal to work towards. Brown states that we need to dismantle and reconstruct the old institutions, that the traditional educational system must be replaced with a polymorphic education provision, an infinite variety of multiple forms of teaching and learning. This is a big ask. He calls for a radical reappraisal of the system and the freedom to let teachers and their students to develop and employ critical thinking interventions and strategies to become more critical, creative and caring in teaching and learning in a wide range of FE contexts. Data from this research-in-progress supports the view that the guiding principles of Community of Inquiry are helpful in framing pedagogical intervention aiming to develop critical thinking. Data also suggests that such interventions can be an accessible way of developing critical thinking through group discussion and investigation. Biesta (2010) calls for a shift in the focus of learning away from centralised curriculum prescription towards more democratic forms of education. The combination of creative pedagogies reported in this chapter appear to be capable not only of opening up spaces where personal narratives and story can be heard and shared but also in the process operate to strengthen connections between theory and practice, enhance professional identity and support the development of critical thinking.

References

Baggini, J. (2005). Wisdom’s Folly. The Guardian, May 12, Retrieved March 3, 2018, from https://www.theguardian.com/theguardian/2005/may/12/features11.g24

Baldissera, L. (2020). Curator as Storyteller: sensing and writing productive refusal. Unfinished PhD Thesis. Goldsmiths University of London. Retrieved May 11, 2020, from https://www.gold.ac.uk/art/research/current-mphil--phd-research/baldissera-lisa/

Barrett, E., & Bolt, B. (Eds.). (2007). Practice as Research Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd..

Biesta, G. (2010). Good Education in an Age of Measurement: Ethics, Politics, Democracy. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers.

Biesta, G. J. J. (2014). The Beautiful Risk of Education. Oxon: Paradigm Books.

Biesta, G. J. J., & Goodson, F. (2010). Narrative Learning. Oxon: Routledge.

Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Company.

Brems, C., Baldwin, M. R., Davis, L., & Namyniuk, L. (1994). The Imposter Syndrome as Related to Teaching Evaluations and Advising Relationships of University Faculty Members. The Journal of Higher Education, 65(2), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.2307/2943923. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/2943923.

Broad, J. H. (2013). Doing It for Themselves: A Network Analysis of Vocational Teachers’ Development of Their Occupationally Specific Expertise. PhD Thesis. Institute of Education, University of London. Retrieved May 4, 2018, from https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?did=5&uin=uk.bl.ethos.630844

Broadhead, S., & Gregson, M. (2018). Practical Wisdom and Democratic Education: Phronesis, Art and Non-Traditional Students. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Brown, K. (1998). Education Culture and Critical Thinking. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Burke, P. J. (2001). Accessing Education: A Feminist Post/Structuralist Ethnography of Widening Educational Participation. PhD Thesis. Institute of Education, University of London. Retrieved May 4, 2018, from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/83899.pdf

Campbell-Galman, S. (2013). The Good, The Bad and the Data: Shane the Lone Ethnographer’s Basic Guide to Qualitative Data Analysis. Oxon: Routledge.

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1998). Becoming Critical: Education Knowledge and Action Research. 8th edn. Oxon: Routledge, Deakin University Press.

Clarke, T., Lee, E., & Matthew, C. (2019). The I’m W.O.K.E. Project: Widening Options Through Knowledge and Empowerment (Paper Given at a Conference). In The 39th Annual International Conference on Critical Thinking and Educational Reform Cultivating the Intellect and Developing the Educated Mind through Critical Thinking. June 4–June 7, 2019 Presented by the Foundation for Critical Thinking in Partnership with CRITHINK EDU, KU Leuven, and University Colleges Leuven-Limburg (UCLL), Belgium.

Coalduca. (2008). Philosophy for Children, by Matthew Lipman, Taken from a BBC Documentary in 1990. (2/7). Retrieved June 29, 2018, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P7fYxuC5lBQ

Coalter, V. (2008) Second Chance Learning and the Contexts of Teaching: A Study of the Learning Experiences of Further Education Students with Few Qualifications. PhD Thesis. University of Glasgow. Retrieved May 4, 2018, from https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?did=25&uin=uk.bl.ethos.495171

Coffield, F. (2008). Just Suppose Teaching and Learning Became the First Priority. London: Learning and Skills Network.

De Bono, E. (1974). The Use of Lateral Thinking. London: Pelican Books.

Department for Education (DfE). (2016). Eliminating Unnecessary Workload Around Planning and Teaching Resources. Retrieved from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/511257/Eliminating-unnecessary-workload-around-planning-and-teaching-resources.pdf

Department of Education (DfE), Kantar Public and Learning and Work Institute. (2018). Decisions of Adult Learners. Retrieved February 10, 2019, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/742108/DfE_Decisions_of_adult_learners.pdf

Dewey, J. (1910, 1933). How We Think. Boston: D.C. Heath.

Dewey, J. (1934). Art as Experience. New York: Pedigree Books, Berkley Publishing Group.

Duff, M. (2018). In Narrative Therapy, Māori Creation Stories are Being Used to Heal. Stuff.com, New Zealand, March 9. Retrieved March 20, 2018, from https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/102115864/in-narrative-therapy-mori-creation-stories-are-being-used-to-heal

Dunne, J. (2005). What’s the Good of Education? In W. Carr (Ed.), Philosophy of Education (pp. 145–158). Abingdon: Routledge Falmer.

Elder, L., & Paul R. (2010). Critical Thinking Development: A Stage Theory with Implications for Instruction. Retrieved August 21, 2018, from http://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/critical-thinking-development-a-stage-theory/483

Elder, L., & Paul, R. (2018). The Aspiring Thinker’s Guide to Critical Thinking. Dillon Beach, CA: The Foundation for Critical Thinking Press.

Eliahoo, R. E. (2014). The Accidental Experts: A Study of FE Teacher Educators, Their Professional Development Needs and Ways of Supporting These. PhD Thesis. UCL Institute of Education. Retrieved May 4, 2018, from https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?did=1&uin=uk.bl.ethos.646041

Fielding, M., Bragg, S., Craig, J., Cunningham, I., Eraut, M., Gillinson, S., Horne, M., Robinson, C., & Thorp, J. (2005). Factors Influencing the Transfer of Good Practice. London: Department for Education and Skills.

Freire, P. (1968). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. London: Penguin Books.

Gregory, M. (2009). Shaped by Stories, The Ethical Power of Narratives. Indiana: University of Notre Dame.

Gregson, M., Nixon, L., Pollard, A., & Spedding, T. (2015b). Readings in Reflective Teaching in Further, Adult and Vocational Education. London, Bloomsbury.

Hitchcock, D. (2018). Critical Thinking. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2018 Edition). Retrieved August 20, 2018, from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/critical-thinking/

hooks, b. (2007). Teaching Critical Thinking, Practical Wisdom. New York: Routledge.

Hyland, T. (2017). Craft Working and the “Hard Problem” of Vocational Education and Training. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 5, 304–325. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.201759021

Kant, I. (1724–1804) in Gregor, M. J. (Trans.) & Denis, L. (Ed.). (2017). Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysic of Morals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lavender, K. (2015). Mature Students, Resistance, and Higher Vocational Education: A Multiple Case Study. PhD thesis. University of Huddersfield. Retrieved May 4, 2018, from http://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?did=1&uin=uk.bl.ethos.691347

Lipman, M. (2003). Thinking in Education (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lipman, M., & Sharp, A. M. (1978). Growing Up With Philosophy. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Lucas, B., & Spencer, E. (2017). Teaching Creative Thinking; Developing Learners who Generate Ideas and can Think Critically (Pedagogy for a Changing World Series). Carmarthen: Crown House.

McNicholas, A. M. (2012). A Critical Examination of the Construct of the Inclusive College with Specific Reference to Learners Labelled as Dyslexic. PhD Thesis. Open University. Retrieved May 4, 2018, from https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?did=3&uin=uk.bl.ethos.582805

McPeck, J. E. (1981). Critical Thinking and Education. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945). Phenomenology of Perception. London and New York: Routledge—Taylor and Francis Group.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative Dimensions. California: Jossey-Bass Inc, Publishers.

Mill, J. S. (1859). ‘On Liberty’, in M. Philp, & F. Rosen (Eds.). (2015). Utilitarianism and Other Essays, Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, C., De Lange, N., & Moletsane, R. (2017). Participatory Visual Methodologies, Social Change and Policy. London: Sage.

Oakeshott, M. (2015). Experience and Its Modes (9th ed.). London: Cambridge University Press.

Ofsted, (2003). The initial training of further education teachers: a survey. London: Ofsted. Retrieved May 11, 2020, from https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20141107081700/http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/resources/initial-training-of-further-educationteachers-2003

Owen, J. (2018). DfE report highlights FE sector’s weaknesses: New research finds problems in areas including teaching and leadership, in Times Educational Supplement. 8 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February, 2019 from https://www.tes.com/news/dfe-report-highlights-fe-sectors-weaknesses

Piaget, J. (1973). To Understand is to Invent, The Future of Education. New York: Grossman Viking Press.

Rogers, C. R. (1994). Freedom to Learn. Ohio: Charles E. Merrill.

Royal College of Art. (2015). Rebalancing Dyslexia and Creativity. Retrieved September 23, 2017, from https://www.rca.ac.uk/news-and-events/news/rebalancing-dyslexia-and-creativity-rca/

Sá, J. (1996). Diary Writing: A Research Method of Teaching and Learning. Paper presented at the Science Education: Research Teachers Practices Conference. University of Evora, Portugal. Retrieved May 11, 2020, from http://www.leeds.ac.uk/bei/Education-line/browse/author/sa__joaquim.html

Schön, D. A. (1991). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Oxon, Routledge.

Scott, D., & Usher, R. (1996). Understanding Educational Research. London: Routledge.

Sennett, R. (2008). The Craftsman. London: Penguin.

Shulman, S. L. (1989). In J. Sá (ed.), Diary Writing: A Research Method of Teaching and Learning. Retrieved September 23, 2017, from http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00001698.htm

Somerson, R., & Hermano, M. L. (2013). The Art of Critical Making: Rhode Island School of Design on Creative Practice. Rhode Island School of Design on Creative Practice. New Jersey: Wiley.

UNESCO, UNICEF, World Bank, UNFPA, UNDP, UN Women and UNHCR, World Education Forum. (2015). Education 2030, Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4. Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for all, 1380_FfA_Cover_8a.indd 1-3 30/08/2016 10:39. ED-2016/WS/2 [Online]. Retrieved May 15, 2019, from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245656

Vygotsky, L. S. (1989). Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Norton, F. (2020). Developing Critical Thinking and Professional Identity in the Arts Through Story. In: Gregson, M., Spedding, P. (eds) Practice-Focused Research in Further Adult and Vocational Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38994-9_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38994-9_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-38993-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-38994-9

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)