Abstract

Minority clients still experience mental health disparities due to barriers in accessing and receiving quality mental health treatments. Research shows that empirically supported treatments (EST) may not be as effective for minority populations. Culturally adapted interventions have shown positive results in decreasing mental health symptoms. However, it is unclear how cultural factors should be included in mental health treatments. This chapter summarizes existing literature on cultural factors (e.g., racial and ethnic match, cultural identity, face concerns) and how they influence treatment processes and outcomes. The proximal-distal model is proposed as a promising framework to guide interventions to be more culturally relevant, and to help clinicians identify potential barriers for their minority clients and adapt treatment for their specific needs.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Culture

- Ethnic minority clients

- Empirically supported treatment

- Mental health disparities

- Culturally adapted interventions

Disparities in health can be defined as the discrepancy between the mental health needs of a certain group compared to the treatment received (McGuire, Alegria, Cook, Wells, & Zaslavsky, 2006). Mental healthdisparities continue to be a pressing problem among minority communities (Cook et al., 2018; Sue, Fujino, Hu, Takeuchi, & Zane, 1991). In a large study, Sue et al. (1991) examined the utilization rates of the mental health system for a five-year period. The authors observed that African Americans had higher utilization rates (20.5%) given their representation in the area (12.8% of the total population) compared to Asian Americans and Latinos utilization rates (3.1% and 25.5%) and their representation in the area (8.7% and 33.7%). The results strongly indicate a pattern of overutilization and, possibly, over-diagnosing certain minority groups, while others have a significant underutilization. Either patterns may not be adequately addressing minority groups mental health needs. More recently, Cook et al. (2018) conducted an extensive literature review including over 600 articles on health disparities and observed that there was no significant change in access to mental health care among minority groups compared to White. The authors observed that factors such as negative attitudes towards mental health, immigrant status, and economic strains were consistently associated with disparities. Clearly, mental health disparities continue to be a pervasive issue that significantly affects minority communities.

Another recent study highlighted the differences in access and diagnosis rates among African American, Latino, and White clients of a large public inpatient service in the Northeast (Delphin-Rittmon et al., 2015). Latino individuals were more likely to access services through crisis-emergency referrals, whereas African American clients were more likely to be referred to services by other inpatient units. Moreover, African American individuals were more likely to receive diagnoses such as schizophrenia, mood disorder, or substance use. On the other hand, Latino clients were more likely to be discharged from the inpatient unit without a conclusive diagnosis (Delphin-Rittmon et al., 2015). These findings suggest that racial and ethnic minority groups may experience systematic biases in treatment which may not account for the culturally specific presentations, values, and beliefs around mental health issues. Being multiculturally competent involves understanding what specific factors affect minority clients and their access to, engagement in, and benefits from mental health treatments. To address mental health disparities, it is crucial to further develop culturally sensitive interventions and test their effectiveness in decreasing mental health problems.

Although mental healthdisparities are pervasive and affect most ethnic minority communities, this review primarily focuses on research involving African American, Asian American, and Latino clients. The dearth of efficacy studies with Native American, Native Alaskan, and Pacific Islander participants is a significant limitation in the literature. This chapter presents and discusses the research on empirically supported treatments for ethnic minorities and the cultural considerations that may impact their effectiveness. In addition, the proximal-distal model is presented to provide one framework of how cultural considerations may be incorporated into research and empirically supported treatments for these clients. Finally, limitations and future directions in this field are discussed.

Empirically Supported Treatments

Empirically supported treatments (ESTs) are described as interventions with research evidence of their efficacy to treat certain conditions (Spring, 2007). Because of their systematic evaluation and demonstrated results across various studies, ESTs are considered best practice for psychological treatment (APA, 2005). ESTs are one of the components of an evidence-based practice, defined as the integration of evidence gathered through research with clinical expertise as well as clients’ characteristics, values, and context (Sackett, Straus, Richardson, Rosenberg, & Haynes, 2000). Sackett et al.’ (2000) definition of evidence-based practice and the American Psychological Association policy (2005) underscore that incorporating the client’s unique characteristics and context is an essential step in the treatment process to enhance outcomes. Spring (2007) explains the treatment decision-making process with the metaphor of a “three-legged stool” comprising of the best available research evidence; clients’ values, characteristics, preferences, and circumstances; and clinical expertise. The metaphor attempts to encapsulate the interdependency of research, clients, and clinical practice as each one informs and is informed by the other.

Although ESTs have demonstrated positive effects in treating a variety of mental health problems, methodological issues limit the generalizability of the results for minority communities. Recently, Spielmans and Flückiger (2018) reviewed 15 meta-analyses on psychotherapy process aiming to investigate potential moderators. The authors examined different study variables that could influence treatment outcomes such as clients’ preferences regarding different treatment modalities, therapist effects, characteristics on treatment, and sample representativeness that directly affects the generalizability of the findings beyond the study sample. The authors pointed out that clinical trials and meta-analyses should include more detailed information about the sample characteristics allowing co-researchers and clinicians to contextualize the results (Spielmans & Flückiger, 2018). In other words, it should be clear in intervention studies where, to whom, and how interventions have shown evidence of their effectiveness. Yet, many studies do not sufficiently describe their participants’ characteristics and do not reflect on the impact of these factors on the results (Spielmans & Flückiger, 2018).

Such limitations should be factored in by clinicians when deciding if and how to implement ESTs. Helms (2015) reviewed three meta-analyses on evidence-based treatments for minority populations and found that most studies conceptualize race and ethnicity as sociodemographic categories instead of examining them as constructs that may affect diagnoses, treatment processes, and outcomes. That is, cultural factors that underlie the racial and ethnic categories may have a significant effect on how mental health and mental health treatments are experienced by minority clients. However, such cultural factors are not accounted for when studies operationalize their variables only as sociodemographic categories. Considering the unique experiences of minorities, researchers and clinicians have tried to adapt ESTs to make them more culturally relevant for diverse communities.

Culturally Adapted Evidence-Supported Treatments

One method to convert ESTs into more “friendly” interventions for minority clients is to adapt them by incorporating specific cultural values, experiences, and contextual circumstances into treatment. Most studies of adapted interventions employ a “top-down” approach where an existing treatment is tailored to a specific group (Bernal & Rodríguez, 2012). Common aspects that are modified in the intervention are the language used to deliver it, the content of the sessions or curriculum, and the inclusion of metaphors and examples that are specific to the target group. Some researchers have criticized the “top-down” approaches, as they tend to make changes that are arbitrary and do not necessarily reflect the community values and circumstances (Hwang, 2006). Other conceptual models of adaptations include “bottom-up” approaches, which emphasize the design of interventions within the cultural context, being that the intervention is originally created for that specific group attending to their needs and resources (Bernal & Rodríguez, 2012). Independently from the conceptual model used, the process of adapting an intervention should be systematic and based on cultural factors that are linked to treatment processes and, thus, relevant to improve outcomes. Yet, many adaptations do not clearly justify the treatment changes, therefore limiting the generalizability of the findings. In this section, the literature on adapted ESTs for minority groups will be reviewed to highlight current findings and challenges in the field.

Griner and Smith (2006) reviewed 76 studies that tested the effects of adapted interventions for minority clients. Participants from all studies (N = 25,225) identified as African Americans (31%), Hispanic/Latino(a) Americans (31%), Asian Americans (19%), Native Americans (11%), European Americans (5%), or not specified (i.e., “other”; 3%). The authors observed that the most common method of adapting the intervention (84% of reviewed studies) was by explicitly incorporating cultural values and beliefs of the target group in the intervention, such as using a cultural folk tale in a storytelling intervention with minority children. The meta-analysis found an overall effect size of d = 0.45 (SE = 0.04, p < 0.0001), indicating a small to moderate effect of adapted interventions in promoting positive outcomes.

However, there was significant variability in the intervention effect sizes across studies indicating that certain characteristics were moderating the outcomes. Variables such as sample (e.g., ethnicity), methodological procedures (e.g., randomization, no group comparison), type of cultural adaptation, and outcome measures (e.g., mental health symptoms, attrition rates) significantly influenced the effectiveness of the intervention (Griner & Smith, 2006). Particularly, clients who identified as Hispanic/Latino(a) (d = 0.56), Asian (d = 0.53), or Native American (d = 0.65), and who were less acculturated to the mainstream American culture (d = 0.50) were found to benefit more from adapted interventions compared to other groups. This finding suggests that the outcomes of adapted interventions are not equally distributed among diverse populations, which highlights the importance of identifying treatment moderators and mediators that are specific to these groups.

The authors also examined the effects of the ethnic match between client and therapist as well as the language spoken by the therapist other than English (Griner & Smith, 2006). Ethnic match refers to the pairing of therapists and clients who have the same ethnic background in an effort to enhance client engagement and the intervention’s cultural sensitivity. The results showed that when ethnic match was attempted, it did not have a significantly higher effect size compared to when there was no report of ethnic match (d = 0.31 versus d = 0.58). This suggests that ethnic match alone may not be a significant factor to improve minority client engagement and treatment outcomes. On the other hand, it was found that when therapy was provided in the same language as the client (other than English) the effect sizes were larger than when there was no report of this characteristic (d = 0.49 versus d = 21). This finding indicates that language match may be more relevant to minority clients than the racial/ethnic match in adapted interventions. Thus, services provided in the client’s preferred language may not only be more accessible for minority clients but may also increase the treatment effectiveness (Griner & Smith, 2006).

A more recent meta-analysis compared the effects of adapted versus non-adapted interventions for minority clients regarding mental health outcomes. Hall, Ibaraki, Huang, Marti, and Stice (2016) found 78 studies and included a total of 13,998 participants in the analyses. Almost all participants identified as non-White individuals (95%): 29% identified as African American, 30% as Asian American or Asian, 26% as Hispanic/Latino(a), 4% as Native American/American Indian/First Nations Canadian, 1% as of Arab descent, 5% as other groups of color, and 5% as of White/European descent. Additionally, a relevant amount (24%) of studies were conducted outside the USA, with adaptations of cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) as the most commonly tested adaptation (36%). Authors found an overall effect size of g = 0.67, indicating that adapted interventions outperformed other conditions promoting better mental health outcomes among minority clients. Also, adapted interventions were found to be particularly effective in treating anxiety and depression symptoms (marginal mean = 0.76) compared to general psychopathology (marginal mean = 0.48; Hall et al., 2016).

Similar to the previous meta-analysis (Griner & Smith, 2006), Hall et al. (2016) observed that certain factors would moderate the effect of adapted interventions. Regarding the study design, studies that compared the adapted intervention with no intervention yielded higher effect sizes in favor of the adapted intervention (marginal OR = 9.8). On the other hand, when the adapted interventions were compared with other manualized treatment, the effect sizes were smaller (marginal OR = 3.47). This emphasizes the importance of employing rigorous methodological designs to accurately capture the efficacy of adapted interventions for minority clients. In terms of the client’s characteristics, the ethnic match between therapist and client was not a significant moderator of these effects (B = −0.51, p = 0.52). In contrast to the previous research study, the language of the intervention other than English was not found to be a significant moderator in this meta-analysis (B = 0.29, p = 0.73). This result may be related to the large number of international studies included in the analyses indicating that adapted ESTs may be as effective in international settings as they are found to be in the USA where they were first developed. Yet, within the U.S., it is possible that less acculturated clients may especially benefit from services that are delivered in languages other than English.

The authors also observed that nearly all of the adapted interventions employed a “top-down” approach by changing parts of a treatment originally designed and tested for other groups (Hall et al., 2016). Although this approach has demonstrated effectiveness in promoting positive outcomes among minority clients, it may neglect cultural-specific manifestations of psychopathology (e.g., neck-induced panic among Cambodian refugees, ataque de nervios—nervous attack—among Latinos/as), values and beliefs around treatment processes, and socially valid coping strategies. These factors significantly impact how researchers and clinicians assess treatment outcomes. Therefore, it is unclear how effective the intervention is in addressing such presentations and engaging minority clients. Despite the methodological limitations, the meta-analysis offers important evidence that adapted treatments are effective in reducing mental health symptoms among minority clients (Hall et al., 2016).

In sum, the findings point to the complex process of adapting treatments to be more culturally relevant and, consequently, engaging and effectively treating minority clients. Studies have pointed to multiple factors that may moderate the effectiveness of adapted interventions among diverse clients such as racial and ethnic group identification, acculturation level, and fluency in English. Moreover, adapting interventions by including cultural values may not be sufficient to significantly increase client engagement and promote mental health outcomes, as it is essential to understand how mental health issues may manifest and in which ways treatment processes may differ for minority clients. It is possible that they perceive, understand, and value treatment components such as treatment goals and techniques differently, which then influence how they engage in the therapeutic alliance and benefit from treatment. In the next section, we will further explore distinct factors that may affect relevant treatment processes for minority groups.

Significance of Cultural Factors in Treatment

As previously highlighted, the literature points to the fact that minority clients may have unique treatment experiences which significantly impact their engagement and outcomes. For instance, a study found that participants who preferred to speak a language other than English tended to endorse an avoidant coping style compared to those who preferred to speak English (Kim, Zane, & Blozis, 2012). An avoidant coping style was significantly associated with negative symptoms and psychological discomfort after treatment. Thus, preference for a different language was related to avoidant style which, in turn, was associated with poorer treatment outcomes. These findings suggest that language preferences may not directly impact treatment outcomes, but this relationship may be mediated by specific factors such as coping styles, which are arguably largely based on cultural values (Kim, Sherman, & Taylor, 2008). In this case, treatments that focus on direct coping styles and strategies may not be sensitive to minority clients who employ more avoidant coping styles as a result of cultural values and norms.

It is also important to examine how the therapist’s cultural background may play a role on treatment processes. Meyer and Zane (2013) assessed three culture-specific elements—racial match between client and therapist, care provider’s knowledge of prejudice or discrimination, and therapist’s ability or willingness to openly discuss issues of race and ethnicity in treatment—in a group of 102 clients in outpatient mental health services and tested for ethnic group differences on these elements. Results showed significant ethnic group differences on two of the three cultural elements: ethnic minority clients reported that it is more important to have a therapist from the same racial background and that the therapist is more knowledgeable of prejudices/discrimination experiences compared to Whites clients (Meyer & Zane, 2013). These preferences may influence how minority clients perceive and engage in mental health treatments. In fact, studies have shown that for a client whose primary language was not English, racial and ethnic match was associated with lower therapy attrition compared to clients whose primary language is English (Sue et al., 1991). The authors found that same ethnic background and same language were significant predictors of positive outcomes for those clients who were less proficient in English, pointing to the importance of considering not only the client’s racial and ethnic background but also their language skills and acculturation level (Sue et al., 1991). These studies are extremely important to be considered in the context of the USA where the majority of psychologists identify as White (84%; American Psychological Association, 2018). Although it may not be possible to always match client and therapist regarding their race and ethnicity, research has shown that having a therapist who speaks the client’s language has a positive effect on outcomes (Griner & Smith, 2006). By being aware of cultural factors that may impact treatment for minority clients, clinicians can actively implement strategies to increase the relevance of interventions.

In general, research indicates that culturally specific factors significantly influence how minority clients perceive, value, and engage in different elements of the therapeutic process. When these factors are not considered, they may negatively affect therapy processes and outcomes. Thus, understanding how to make mental health treatments more valid and engaging for minority clients is essential to better serve these communities. In the next section, we will introduce a conceptual model that provides a framework to examine the influence of culture on treatment and treatment outcomes.

Cultural Influences in Treatment: The Proximal-Distal Model

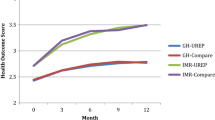

When exploring the role of culture in treatment processes and client outcomes, it is important to identify the specific factors involved. There are few conceptual models or clinical approaches that systematically articulate how cultural factors may affect the treatment process and outcomes. The proximal-distal model (Sue & Zane, 1987) provides one such framework to articulate the effects of cultural differences in psychotherapy with minority clients. As the model shows (Fig. 8.1), there is an interface between specific cultural factors and important treatment processes that cause and/or exacerbate the issues for these clients. For instance, cultural differences in communication style between therapist and client could affect establishing an effective therapeutic alliance. The cultural elements (e.g., worldviews, help-seeking belief, communication styles) may affect key treatment processes (e.g., treatment credibility, client engagement, self-disclosure, treatment goals), which in turn affect treatment outcomes. Therefore, ethnic and cultural variations between client and therapist may be examined in terms of distal variables (e.g., communication styles) influencing more proximal variables (e.g., self-disclosure) that are experienced in treatment and have an impact on outcomes (Sue & Zane, 1987). By using the model as a framework to understand clinical work with minority clients, researchers and clinicians may identify and explore hypotheses related to how the client’s cultural background may influence treatment. Moreover, based on this framework, adaptations and strategies can be elaborated to better serve minority communities. Treatment credibility is a robust predictor of treatment effectiveness and particularly important for minority clients (Kazdin & Wilcoxon, 1976). The proximal-distal model has identified three domains that may negatively impact treatment credibility: (1) problem conceptualization, (2) coping strategies and problem-solving, and (3) treatment goals (Huang & Zane, 2016).

Proximal-distal model (Adapted from Huang & Zane, 2016)

Problem Conceptualization

This domain refers to how the intervention conceptualizes or explains the client’s difficulties according to its theoretical orientation. The problem conceptualization guides the therapeutic strategies that are used and how the therapist will evaluate the outcomes. However, the client’s cultural beliefs and values may shape how they perceive their mental health issues. The incongruence/discrepancy between therapist and client problem conceptualization may negatively affect therapy process and results. For instance, Asian American clients, who tend to endorse that mind and body are deeply interconnected, may emphasize more the role of somatic symptoms (e.g., headaches, stomachaches) in mental health compared to White clients (Lin & Cheung, 1999). This may influence the credibility (i.e., the extent to which the client believes the therapist is effective, trustworthy, and an expert to help them; Sue & Zane, 1987) of clinical practices that do not include somatic symptoms and strategies to improve the client’s well-being. The tendency for some clients, particularly ethnic minority clients, to express mental health symptoms somatically goes counter to more Western-based, cognitive perspectives of mental health, which conceptualize mental health problems as a result of maladaptive cognitions rather than somatic experiences. Therefore, the discrepancy between therapist and client conceptualizations of the mental health problem may diminish therapeutic alliance and treatment credibility. In fact, there is evidence showing that agreement between therapist and client regarding the perceived problem would predict short-term positive outcomes while controlling for client’s racial and ethnic background (Zane et al., 2005).

Minority clients may present and/or focus on certain mental health issues according to their cultural values and perspectives. As previously mentioned, Asian American as well as Latino clients tend to present more somatic symptoms compared to other groups (Flaskerud, 1986; Lin & Cheung, 1999). These somatic complaints are often culturally valid expressions of distress that lead to less stigmatizing help-seeking behaviors among minority populations (Hwang, Myers, Abe-Kim, & Ting, 2008). For example, Chinese patients diagnosed with depression tend to report only somatic complaints and not mention emotional complaints in their first visits to the psychiatrist compared to White patients who would emphasize the emotional disturbances. This difference is thought to be related to the cultural tendency to not disclose emotional distress to others as well as the high prevalence of mental health stigma in Asian cultures (Hwang et al., 2008).

Guarnaccia, Lewis-Fernández, and Marano (2003) interviewed 121 Puerto Ricans who had experienced a cultural-specific condition, ataque de nervios (i.e., nervous attack) following an environmental disaster in the island. Participants described the condition as the combination of social, emotional, and physical symptoms (e.g., no control over behaviors and emotions, tension, loss of consciousness). The authors highlighted that Latino individuals often talk about nervios (i.e., nerves) instead of mental health diagnoses because it is a more culturally meaningful concept. Additionally, suffering from nervios is related to social causes such as familial trauma and loss, which provides a cultural framework to understand problems (Guarnaccia et al., 2003). Thus, factoring in somatic and physical presentations in treatment may help minority clients, whose cultures emphasize the mind and body connection, to better express their distress and address their concerns in culturally relevant ways. ESTs that are structured and manualized may not account for the cultural variations in conceptualizing mental health problems.

Coping Strategies and Problem-Solving

This domain is defined by the potential cultural differences in coping and problem-solving strategies between client and therapist. In order for ESTs to be more culturally relevant, they may need to propose clinical strategies that address mental health symptoms that are valid or normative according to the client’s cultural background. For example, earlier studies have shown that Asian American clients prefer more directive, explicit, and pragmatic therapeutic interventions compared to White clients (Arkoff, 1959; Meredith, 1966). Although some evidence-based approaches are more structured and solution-focused (e.g., cognitive-behavior therapy; CBT), they may also assume that the individual has the primary control over their life events to implement these strategies and do not consider the involvement of significant others and the larger community (Iwamasa, Hsia, & Hinton, 2006). Minority clients who come from more collectivistic cultures, such as Asian and Latino cultures, may find this individualistic approach inappropriate or incongruent with their beliefs regarding the involvement of family and the respect for elders. In this case, a client from a more collectivistic culture may find interventions that focus exclusively on the individual as less relevant and, consequently, benefit less from it.

Research has found that minority individuals may endorse different coping strategies to address stress and interpersonal conflicts compared to White individuals (Lam & Zane, 2004). A study examined the coping styles of Asian and White Americans and observed significant differences between the two groups. White participants endorsed more strategies such as changing the nature of the stressor (i.e., primary control). Conversely, Asian participants endorsed more strategies that change how they feel and think about the stressor (i.e., secondary control). The results suggest that an intervention that focuses mainly on primary control may be less relevant for Asian clients who are less oriented towards this type of coping strategy. In fact, authors found that orientation towards the individual’s independence fully mediated the ethnic difference in preference for primary control. White participants were significantly more oriented towards individual independence compared to Asian participants, and those participants who were more independence-oriented also endorsed more primary control (Lam & Zane, 2004). Considering that many psychological interventions were developed and tested in the context of Western culture that emphasizes independence, self-reliance, and autonomy (Markus & Kitayama, 1991), the recommended coping strategies tend to reproduce these values emphasizing independence and primary control over interdependence and secondary control. For minority clients who are less oriented towards Western values, this approach can be less socially acceptable or applicable to their lives.

Another study compared coping strategies endorsed by African American and White community college students (Ayalon & Young, 2005). The authors observed that African American students reported less use of psychological services compared to their White counterparts (34.3% vs 53%). On the other hand, the former group was more likely to endorse spiritual coping strategies and seek help from their religious community (87.1% vs 74.2%, p < 0.01). Moreover, African American students endorsed more external sources of control (e.g., God, powerful others, chance) as explanations for their psychological symptoms than White students (Ayalon & Young, 2005). These results suggest that for this minority group, religious beliefs have a significant role in understanding and coping with psychological stress. Not accounting for these factors may negatively impact trust and alliance in the therapeutic work. Indeed, research has pointed to the importance of incorporating spirituality into treatment with African American clients since it is a salient cultural value (Snowden, 2001).

By being aware of cultural differences in coping strategies, clinicians can incorporate the client’s orientation into treatment to improve engagement and outcomes. For instance, clients who shared the same coping orientation (e.g., avoidant coping style) with their therapists at pretest reported less discomfort and less depressive symptoms after four sessions compared to a client who did not share the same coping orientation with their therapists (Zane et al., 2005). The findings point to the effect of cultural variance in coping and problem-solving orientation. Interventions that endorse strategies that are not culturally acceptable or congruent with the client’s values may have less effect on treatment outcomes for minority clients.

Treatment Goals

This domain highlights the importance of clients’ perceptions about therapy goals and outcomes, which may vary from those identified by the therapist. Early studies have shown that East Asian and Western psychotherapies diverge from what they consider as the treatment primary goal (Murase & Johnson, 1974). While East Asian therapies emphasize recovery and improvement of the client’s roles in society, such as being a good worker or fulfilling their role as a parent or spouse, Western therapies emphasize reduction of client’s stress related to their life or identity. This comparison clarifies the underlying social values that shape how therapy may be perceived by minority clients. According to the proximal-distal model, there may be dissonance between a client’s expectations of the treatment and the actual proposed treatment (by the therapist) due to relevant cultural differences that will ultimately affect the effectiveness of the intervention for certain groups. For instance, a minority client who is oriented towards rehabilitation to their social roles may perceive a treatment that focuses on reducing stress to be ineffective because the client’s primary goals with treatment are not aligned with the goals of that treatment. Research found that when clients and therapists had similar treatment goals, clients tended to report better outcomes compared to when the goals differed (Zane et al., 2005). Moreover, when there was agreement on treatment goals, clients reported perceiving their sessions as more impactful, feeling more comfortable in sessions, and having more positive perceptions about the work in the sessions.

Family support and cohesion are also salient aspects of Latino culture. Domenech Rodríguez, Baumann, and Schwartz (2011) described the systematic adaptation of a parenting intervention for Latino families. During focus groups, participants identified superación (i.e., the child going beyond the parents’ achievements) and educación (i.e., the child being competent and respectful toward adults) as important parenting goals within their culture. The cultural value of respect (i.e., respect to elders) was underscored as another relevant factor shaping family interactions. After identifying these concepts associated with parenting, the authors framed the treatment goals in a more culturally valid way. For instance, parental encouragement was linked to promotion of educación and respecto. The adaptations were effective in retaining families longer in the intervention and promoting positive parenting behaviors (e.g., limit setting) at comparable rates with other samples (Domenech Rodríguez et al., 2011). The results suggest that framing treatment goals and interventions according to the client’s cultural values can significantly increase treatment engagement.

The proximal-distal model provides a framework to investigate and assess the effect of cultural factors on treatment processes and outcomes. In addition to the three domains mentioned above, there are other cultural factors that may directly impact the credibility of ESTs among minority clients.

Cultural Identity

The literature has demonstrated that African American clients tend to mistrust mental health services, especially when the therapist is White (Cabral & Smith, 2011; Whaley, 2001). In fact, as discussed before, African American patients tend to be overdiagnosed and overrepresented in inpatient units (Sue et al., 1991). Whaley (2001) conducted a systematic review focusing on cultural mistrust, or skeptic attitudes and beliefs towards White individuals including therapists, in the context of mental health services. The author examined 22 studies and found a moderate effect size (r = 0.303), indicating that African American clients experience cultural mistrust in therapy as they experience in other social interactions (Whaley, 2001). Client’s attitudes towards the therapist may explain some barriers to building an effective therapeutic alliance with minority clients. Particularly for African American communities, having a White therapist may increase their cultural mistrust in therapy and hinder treatment outcomes.

Besides the therapist racial/ethnic identity, their therapeutic style (e.g., more or less directive) may be perceived in a variety of ways affecting the treatment process. Wong, Beutler, and Zane (2007) conducted an experiment to test how ethnicity would influence perceptions of therapist credibility (i.e., how credible and effective they found the therapist) depending on the therapeutic style used. Asian and White American participants observed expert therapists using a directive or nondirective approach in a therapy session and reported on their reactions to the therapists. Results showed that Asian American participants rated the nondirective sessions lower in credibility and working alliance compared with White participants. Additionally, Asian American participants found that nondirective therapists were less easy to understand, and this perception was significantly associated with lower rates of intervention credibility as well (Wong et al., 2007). In this case, the minority (i.e., Asian American) clients’ perspectives of their therapists were negatively impacted by their treatment approach preference (i.e., directive over nondirective). These perceptions may, in turn, negatively impact their treatment responses or outcomes.

Similar results were observed in a study that compared the credibility of two ESTs, cognitive therapy and time-limited dynamic psychotherapy, among Asian American participants (Wong, Kim, Zane, Kim, & Huang, 2003). Participants were randomly assigned to read about one of the approaches for treating depression and reported on their perceptions of treatment credibility. Findings showed that Asian American participants with lower levels of White identity perceived cognitive therapy to be more credible than dynamic therapy. On the other hand, Asian American participants with higher levels of White identity did not perceive the two approaches differently (Wong et al., 2003).

A mixed-methods study examined differences in therapeutic styles between Latino and non-Latino clinicians (Lu, Organista, Manzo, Wong, & Phung, 2001). Participants rated their style according to three primary domains: direct, instrumental, and relational. The authors found that Latino clinicians endorsed less direct and instrumental styles and more relational styles compared to non-Latino clinicians. Interviews with the clinicians supported these findings; Latino clinicians emphasized that developing a strong relationship with Latino clients and their families is crucial for treatment engagement (Lu et al., 2001). Reinforcing this view, Perez (1999) argues that therapists could integrate components of interpersonal therapy (IPT)—which focuses on restoring interpersonal relations—into conventional cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) to make it more relevant and effective for Latino communities. Overall, the research highlights that cultural factors such as ethnicity, cultural identity, and endorsement of Western values may moderate treatment credibility, which, in turn, may affect treatment engagement and its effects on mental health.

Face Concern

Face has been defined as an individual’s set of claims about their character and integrity that are socially sanctioned and defined based on roles that the individual is expected to fulfill as a member of a certain group (Zane & Yeh, 2002). This concept was previously identified as playing an important role in defining interpersonal dynamics in Asian social relations and, consequently, associated with help-seeking behaviors (Shon & Ja, 1982; Sue & Morishima, 1982). In Asian interpersonal relations, individuals are expected to behave in a certain way in order to avoid losing face. This is problematic, since common treatment processes that characterize Western psychotherapies, such as diagnosis of mental health symptoms and self-disclosure of personal experiences, may elicit negative reactions in individuals concerned with losing face. Stigma and stereotypes around mental illnesses are a significant barrier to seeking treatment for many minority groups (Gary, 2005). For instance, among Chinese immigrants, stigma towards mental illnesses is higher when it is associated with the individual’s inability to work and be productive in society (Yang et al., 2014). That is, having a diagnosis of mental illness may be perceived as failing to fulfill important social roles (e.g., work) or losing face, which subsequently decreases the chance of the individual seeking help. Furthermore, a core part of psychotherapies (such as CBT) requires clients to self-disclose their thoughts and emotions. Self-disclosure may be an issue for minority clients whose cultures value privacy and limited exposure of problems to strangers, especially when related to interpersonal issues. For instance, self-disclosing about problems or conflicts with other people may evoke feelings of shame in minority clients who could be concerned about saving face. As a result, concerns about face loss may significantly influence treatment processes such as establishing a positive therapeutic relationship, engaging the client in treatment, and using therapeutic strategies.

As observed, face loss may be an important concept to understand the unique experience of minority clients in the context of psychological treatment. Zane and Yeh (2002) developed and validated the Face Loss Questionnaire comprised of 21 items assessing the extent to which the responder is concerned about face. The measure was tested with White and Asian American participants yielding high levels of reliability α = 0.83 (Zane & Yeh, 2002). Additionally, the authors found that face concern was positively correlated with concerns about others, private self-consciousness, and public self-consciousness, and negatively correlated with extraversion, tendency to perform before others, and White cultural identity. Importantly, ethnic differences were observed regarding levels of face concern; Asian American participants reported higher levels of face concern compared to White Americans (Zane & Yeh, 2002).

Research using this instrument has shown that individuals who are highly concerned with face tend to be less inclined to self-disclose their personal values/feelings, private habits, close relationships, and sexual issues (Zane & Ku, 2014). Moreover, the authors tested the effect of gender and ethnic match between therapist and client on the levels of self-disclosure. They found that gender match improved disclosure of sexual issues while the ethnic match did not increase self-disclosure, indicating that clients who are concerned about losing face do not benefit from having a therapist from the same ethnic background to increase self-disclosure (Zane & Ku, 2014). This is possibly because clients will attempt to save face irrespective of their conversational/interactional partner.

Another study examined the impact of face concerns on treatment credibility (Park, Kim, & Zane, 2019). Results showed that minority participants who reported higher levels of face concern preferred a more directive therapist. That is, face concern moderates the participants’ preferences on the therapist’s counseling style. A possible explanation is that those who are more concerned about face social roles may see the therapist as an authority figure from whom they receive advice and directives. In this sense, a therapist whose style is less directive may be also seen as less credible, as it becomes unclear to certain minority clients the roles and structure of the treatment. These results highlight the importance of understanding the specific cultural factors that affect therapy processes, such as face concern, to better address minority clients’ needs.

Racial and Ethnic Match Between Therapist and Client

Having a diverse staff in mental health clinics and agencies can be attractive to minority clients and reflect the diversity in the communities themselves. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, matching therapist and client racial and/or ethnic background (i.e., racial and ethnic match) may not directly translate into more culturally competent services (Flaskerud, 1986; Sue, 1977). Meta-analyses (Cabral & Smith, 2011; Maramba & Nagayama Hall, 2002) have reviewed the effects of the racial and ethnic match between therapist and client on treatment outcomes and dropout rates. It was often expected that minority clients who shared similar cultural backgrounds with their therapists would benefit more from therapy and have lower dropout rates compared to minority clients who had a therapist from a different background. In fact, Maramba and Nagayama Hall (2002) found significant but small effect sizes for treatment utilization (r = 0.04, p < 0.001) and dropout (r = 0.04, p < 0.001) rates when therapist and client were ethnically matched. Moreover, the effect sizes were significantly larger for ethnic minority clients compared to White clients. That is, the racial and ethnic match is particularly beneficial for minority clients. On the other hand, when analyzing treatment outcomes at termination, the authors did not find significant differences between clients who had ethnic matched therapists and those who did not (r = 0.01, p > 0.05; Maramba & Nagayama Hall, 2002). Possibly, the match has stronger effects in the beginning of the treatment when cultural differences may lead to early dropout or poor therapeutic alliance. Once the work alliance and treatment goals are established, ethnic match may have a smaller effect.

Another meta-analysis found similar results. Cabral and Smith (2011) calculated the effect sizes of 52 studies investigating the client’s preferences for a therapist from the same race/ethnicity. Results showed that clients tended to have a moderately strong preference for a therapist of the same racial/ethnic background (r = 0.63, p < 0.001). However, when it came to therapeutic outcomes, the authors found small effect sizes (r = 0.09, p < 0.001) indicating that there was a small difference between clients working with matched therapists versus unmatched therapists. Examining preferences across racial groups, the authors observed significant differences: African American participants reported higher preferences (d = 0.88) for matched therapists compared to other groups (Asian Americans d = 0.28; Hispanic/Latino Americans d = 0.62; White/European Americans d = 0.26; p = 0.03; Cabral & Smith, 2011). This finding suggests that for African American clients, the racial and ethnic match between therapist and client is more salient than for other minority clients.

Thompson and Alexander (2006) randomly assigned 44 African American clients to either an African American or a White therapist. Therapy modality (i.e., problem-solving and interpersonal) was also randomly assigned and controlled through close supervision of each session. After treatment (i.e., maximum of 10 sessions), clients rated their symptom levels and perceptions about therapy. Results showed no moderation of racial match on therapy outcomes. However, clients who had an African American therapist had significantly higher ratings of understanding and acceptance of treatment goals and strategies while controlling for therapy modality (Thompson & Alexander, 2006). These studies underscore that African American clients may benefit more from sharing their racial/ethnic background with their therapist compared to other minority groups. As discussed in previous sections, this may be related to cultural mistrust (Whaley, 2001). Thus, culturally sensitive ESTs should consider the particularities of the communities and integrate them into treatment to maximize outcomes.

The literature on cultural factors, as highlighted by the proximal-distal model, points to the critical fact that minority clients may perceive and value different aspects of their therapist and therapy approaches compared to White clients. Such differences may not be explicit in ESTs that are, overall, developed for and tested mainly with White clients. ESTs that do not consider the experiences and values of minority clients may not be as effective for these populations. Furthermore, these treatments may unintentionally perpetuate disparities in mental health by offering interventions that may not be valid for minority clients. These limitations of ESTs in addressing minority clients’ needs are even more pronounced when we consider culturally relevant treatments for minority adolescents and children. In the next section, the available literature in this area is presented to highlight ways that minority youth and their families may particularly benefit from ESTs that account for their context and cultural background.

Empirically Supported Treatments for Minority Adolescents and Children

Research has shown that adolescents and children from diverse backgrounds have similar or even higher mental health needs compared to their non-Hispanic White peers (Georgiades, Paksarian, Rudolph, & Merikangas, 2018). For instance, a study analyzed data from more than 6000 adolescents ages 13–18 years and found that minority teens were as likely as their White peers to develop mood or anxiety disorders (Hispanic: AOR = 1.30; non-Hispanic Black: AOR = 1.14; Asian: AOR = 1.07, ps > 0.05). However, when looking at service use rates, minority youth were significantly less likely to receive mental health treatments compared with their White counterparts (Hispanic: AOR = 0.7; non-Hispanic Black: AOR = 0.54, ps < 0.01; Asian: AOR = 0.8, p > 0.05; Georgiades et al., 2018). These findings suggest that although minority youth experience the same levels of mental health problems as their White counterparts, they do not engage in treatment as much, possibly, because of significant barriers to access these services. Moreover, youth depend on their parents/caregivers to access services (Stiffman, Pescosolido, & Cabassa, 2004). In minority families, caregivers may have limited English fluency to understand and interact with the health system, have concerns about their immigration status, and lack insurance coverage to utilize services preventing youth from receiving treatment (Georgiades et al., 2018; McGee & Claudio, 2018). Thus, it is particularly important to engage minority adolescents, children, and their parents/caregivers in mental health treatments that effectively address their difficulties and foster a healthy development.

Nevertheless, there is a lack of methodologically sound research studies that evaluate the effectiveness of interventions among minority adolescents and children. One of the few systematic reviews examining the evidence supporting mental health treatments for minority youth was conducted by Huey and Polo (2008). The authors aimed to identify ESTs targeting behavioral and emotional problems among adolescents and children. The meta-analysis included 25 different control trials yielding an overall moderate effect size of d = 0.44 (SE = 0.06) at posttreatment. Overall, the results support the effectiveness of ESTs for minority youth favoring their implementation to address mental health issues (Huey & Polo, 2008).

The authors also analyzed the difference between culturally enhanced interventions in comparison to regular ones (Huey & Polo, 2008). The evidence was not consistent in supporting the idea that culturally enhanced interventions promote better outcomes compared to non-adapted interventions. Such findings may be due to the small sample sizes in the studies and the inaccuracy in measuring and assessing the quality of the cultural adaptation that was used (Huey & Polo, 2008). Yet, the authors highlight the importance of considering the family’s values when tailoring interventions to the youth’s social and cultural context. It is particularly important to identify individual factors (e.g., ethnic identity, developmental level, gender) that are significantly related to treatment processes and can guide how interventions are translated to “real world” settings. That is, researchers should focus on how ESTs are implemented in minority communities that face a variety of barriers to services that are not accounted for in “lab” settings (Huey & Polo, 2008).

Another systematic review conducted by Jackson (2009) focused on evaluating culturally sensitive prevention interventions for minority youth. Using the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse’s Scientific Rating Scale (CEBC, 2007), which is a systematic method to evaluate the extend of evidence supporting an intervention, the author classified the various studies using a range. The classification ranged from level 1—Superior, which describes research employing experimental designs with an equivalent control and comparison group, to level 5—concerning, which describes no evidence of positive change. The author examined 15 studies and found that eight of them were at level 3—efficacious, as the interventions demonstrated efficacy over the control group or comparable to another intervention in quasi-experimental studies. Four interventions were classified as level 2—effective. That is, they employed an experimental design with random assignment to conditions and observed a significant reduction in the target behavior among the participants assigned to the intervention condition (Jackson, 2009). In general, these results suggest that there is empirical support for ESTs for minority youth. However, there is an urgent need for further research in this area including experimental designs and larger youth samples from different racial and ethnic backgrounds to clearly identify culturally relevant treatments for this population. Moreover, research should focus on the specific factors that are implicated in treatment processes and outcomes for minority adolescents and children. As highlighted in previous sections, studies including adult samples are growing in number and yielding important results to guide interventions. In the same way, studies including youth samples must increase in number to provide clearer data about effective interventions and salient factors affecting mental health outcomes. In the next section, considerations of limitations in this field and future directions for research are presented.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are important limitations in the evaluation research that has been conducted particularly regarding the effectiveness of culturally adapted interventions for minority populations. Often, the culturally adapted intervention is compared to the non-adapted intervention for the same community in terms of treatment outcomes. When the results of these studies show that the culturally adapted intervention is as effective as the non-adapted intervention, there is a tendency to conclude that the non-adapted one should be preferred, since there is no difference between them. However, the results could be interpreted as showing that the adapted intervention is in fact as effective as the original intervention suggesting the former holds the therapeutic components of the latter. Moreover, given they have the same effects, the adapted intervention should be preferred over the non-adapted one because it is more socially valid for the target community by incorporating cultural aspects while maintaining similar effectiveness. Research aiming to better evaluate the effects of ESTs for minority clients may benefit from the critical process approach (CPA; Zane, Kim, Bernal, & Gotuaco, 2016), as it offers a systematic guideline to adapt interventions for minority clients and identify critical treatment components that can be tailored to the specific population. Therefore, evaluation studies may test the effects of specific variables and determine the equivalency between adapted and non-adapted interventions. Again, the adapted intervention should be seen/acknowledged to be as effective as the non-adapted intervention and not necessarily superior to it. This approach may be extremely positive for advancing the field and disseminating the use of ESTs for minority populations.

Nonetheless, there are other significant challenges particularly related to the lack of theoretical models that support the adaptation of interventions while considering relevant treatment processes and outcomes. Few researchers employ a bottom-up approach when adapting an intervention for a specific population (Hall et al., 2016). Most of the studies select cultural values that they consider relevant to integrate in the intervention. However, there is a lack of evidence regarding whether the selected cultural values are associated with increasing treatment credibility in the target population. One possible systematic approach to cultural adaptations is Kazdin’s (1977) conceptualization of the social validity of treatments. This conceptual model supports the idea that diverse groups may hold unique perceptions, understanding, and acceptability levels of mental health treatments which significantly impact how they engage in them. The framework encouraged further work, such as the development of assessment tools of treatment social validity (Reimers & Wacker, 1988) that, in turn, can inform the adaptation process of interventions. Based on ratings of social validity and the consideration of the specific components that are not socially valid, researchers can more accurately modify interventions that will be more culturally informed and relevant.

Conclusions

For cultural minority clients, mental health disparities involve critical problems and difficulties in access, engagement, and benefit from psychological interventions. This review indicates that cultural factors influence treatment and may challenge the implementation of ESTs with minority clients. There are a multitude of cultural issues that may affect the treatment experience of these clients. However, the pressing and continuing challenge for clinicians centers on how to systematically apply this empirically based knowledge to provide culturally competent care. We propose the proximal-distal model as one promising and practical strategy in which clinicians can generate and test working hypotheses to enhance the treatment impact and experience for minority clients by addressing specific cultural issues that may mitigate certain treatment processes and outcomes. In this approach, the major premise nominates treatment credibility as the primary treatment process that cultural issues often adversely affect which, in turn, negatively impacts treatment outcomes. Treatment credibility is a critical treatment process that has been linked to treatment outcomes, (Kazdin & Wilcoxon, 1976) as well as treatment utilization (Kim & Zane, 2016). Clinicians can generate working hypotheses as to how a certain cultural issue may affect credibility. For example, there is evidence that minority clients may benefit from racial/ethnic match with their therapist (e.g., Cabral & Smith, 2011), particularly African American clients. However, ethnic mismatches between White therapists and African American clients often occur. In these cases, some research suggests that White clinicians should hypothesize that cultural mistrust may be a significant barrier to developing an effective therapeutic alliance with African American clients (Whaley, 2001). Failure to do so may contribute to serious problems in the therapist’s credibility. On the other hand, for certain Asian American clients, face and shame issues may hinder the necessary and critical process of open self-disclosure in treatment (Zane & Ku, 2014). To maintain their credibility and influence in treatment, clinicians may need to use specific face restoration strategies, such as encouraging clients to problem-solve to demonstrate their mastery and control. Similarly, there is evidence to indicate that folding in the value of respecto (i.e., respect) when working with Latino families may significantly enhance the therapist’s credibility and the client’s engagement in treatment (Bernal & Rodríguez, 2012). Clinicians may hypothesize that this approach may be more valid and have more credibility with their clients than a more traditional one that frames problems as mental health disorders. As such, they may frame familial conflict in terms of a lack of respect and offer strategies to solve these interpersonal problems.

ESTs have shown positive effects among minority populations, yet challenges remain in truly determining if they are “friend” or “foe” for minority clients. For one, ESTs are developed from the Western, predominately White mainstream perspective, and even the adaptation of these interventions is still taking the mainstream perspective and applying it to minority communities (i.e., top-down process). The use of frameworks such as the proximal-distal model can help guide the process of translating research to practice. This model is promising, but it is not the only one available. Hwang’s (2006) psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework (PAMF) was developed to help clinical researchers adapt ESTs for ethnic minority clients and for training mental health professionals. This framework includes four domains to assist in the adaptation of ESTs, including (1) dynamic issues and cultural complexities (i.e., awareness of clients’ identities and group membership), (2) orientation (e.g., how they orient therapy, treatment goals and structure, beliefs about disease development), (3) cultural beliefs (e.g., cultural bridging to relate treatment concepts to clients), and (4) client-therapist relationships (e.g., understand how client’s cultural beliefs influenced their help seeking, clearly address client-therapist roles and expectations). More frameworks like the PAMF and proximal-distal model are needed to facilitate the development of “friendly” ESTs for minority clients.

Another way to identify “friendly” ESTs is to diversify our research in this field. Many forms of interventions may already exist that are indigenous to communities of color, or originate from the countries from which minority clients emigrated. For example, a recent review of literature found that tai chi was effective at decreasing depression symptoms for Asian clients (Berger, Huang, & Zane, in press). Another study found a Lishi intervention to be effective at promoting treatment engagement and mental health outcomes in a sample of Southeast Asian elderly adults (Huang et al., in press). Since ESTs are anchored in mainstream, White culture, including indigenous treatments in EST research may propel the field in ways that benefit minority communities.

Finally, researchers should be examining their own practices and policies in how they approach and describe issues of diversity. Currently, the general practice is for researchers to describe how their research findings may be generalizable to minority populations. If the intention of creating “friendly” ESTs is truly serious, researchers should be more explicit about how their treatment may only be applicable to Whites and how it may be limited for other groups. This will allow other researchers to build upon those limitations and design studies that are targeted specifically for minority populations. Journals can facilitate this practice by instituting policies that require authors to explicitly discuss their research findings using this format. Taking these meaningful steps will likely push the field toward providing culturally informed and effective ESTs for cultural minority clients and their communities.

References

American Psychological Association. (2005). Policy statement on evidence-based practice in psychology. Retrieved from: https://www.apa.org/practice/guidelines/evidence-based-statement.aspx

American Psychological Association. (2018). Demographics of the U.S. psychology workforce: Findings from the 2007–16 American Community Survey. Washington, DC: Author.

Arkoff, A. (1959). Need patterns in two generations of Japanese Americans in Hawaii. The Journal of Social Psychology, 50(1), 75–79.

Ayalon, L., & Young, M. A. (2005). Racial group differences in help-seeking behaviors. The Journal of Social Psychology, 145(4), 391–404.

Berger, L., Huang, C. Y., & Zane, N. W. (in press). Integrating approaches to advance research on culturally informed evidence-based tCabraleatments for Asian Americans. In F. Leong & G. Bernal (Eds.), Clinical psychology of ethnic minorities: Integrating research and practice.

Bernal, G., & Rodríguez, M. M. D. (2012). Cultural adaptations: Tools for evidence-based practice with diverse populations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Cabral, R. R., & Smith, T. B. (2011). Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: A meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 537–554.

Cook, B. L., Hou, S. S. Y., Lee-Tauler, S. Y., Progovac, A. M., Samson, F., & Sanchez, M. J. (2018). A review of mental health and mental health care disparities research: 2011–2014. Medical Care Research and Review, 00(0), 1–28.

Delphin-Rittmon, M. E., Flanagan, E. H., Andres-Hyman, R., Ortiz, J., Amer, M. M., & Davidson, L. (2015). Racial-ethnic differences in access, diagnosis, and outcomes in public-sector inpatient mental health treatment. Psychological Services, 12(2), 158–166.

Domenech Rodríguez, M. M., Baumann, A. A., & Schwartz, A. L. (2011). Cultural adaptation of an evidence-based intervention: From theory to practice in a Latino/a community context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47(1–2), 170–186.

Flaskerud, J. H. (1986). Diagnostic and treatment differences among five ethnic groups. Psychological Reports, 58(1), 219–235.

Gary, F. A. (2005). Stigma: Barrier to mental health care among ethnic minorities. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 26(10), 979–999.

Georgiades, K., Paksarian, D., Rudolph, K. E., & Merikangas, K. R. (2018). Prevalence of mental disorder and service use by immigrant generation and race/ethnicity among US adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(4), 280–287.

Griner, D., & Smith, T. B. (2006). Culturally adapted mental health intervention: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43(4), 531–548.

Guarnaccia, P. J., Lewis-Fernández, R., & Marano, M. R. (2003). Toward a Puerto Rican popular nosology: nervios and ataque de nervios. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 27(3), 339–366.

Hall, G. C. N., Ibaraki, A. Y., Huang, E. R., Marti, C. N., & Stice, E. (2016). A meta-analysis of cultural adaptations of psychological interventions. Behavior Therapy, 47(6), 993–1014.

Helms, J. E. (2015). An examination of the evidence in culturally adapted evidence-based or empirically supported interventions. Transcultural Psychiatry, 52(2), 174–197.

Huang, C. Y., & Zane, N. (2016). Cultural influences in mental health treatment. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 131–136.

Huey, S. J., & Polo, A. J. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 262–301.

Hwang, W. (2006). The psychotherapy adaptation and modification framework: Application to Asian Americans. American Psychologist, 61, 702–715.

Hwang, W. C., Myers, H. F., Abe-Kim, J., & Ting, J. Y. (2008). A conceptual paradigm for understanding culture’s impact on mental health: The cultural influences on mental health (CIMH) model. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(2), 211–227.

Iwamasa, G. Y., Hsia, C., & Hinton, D. (2006). Cognitive-behavioral therapy with Asian Americans. In P. A. Hays & G. Y. Iwamasa (Eds.), Culturally responsive cognitive-behavioral therapy: Assessment, practice, and supervision (pp. 117–140). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Jackson, K. F. (2009). Building cultural competence: A systematic evaluation of the effectiveness of culturally sensitive interventions with ethnic minority youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 31(11), 1192–1198.

Kazdin, A. E., & Wilcoxon, L. A. (1976). Systematic desensitization and nonspecific treatment effects: A methodological evaluation. Psychological Bulletin, 83(5), 729–758.

Kazdin, A. E. (1977). Assessing the clinical or applied importance of behavior change through social validation. Behavior Modification, 1(4), 427–452.

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., & Taylor, S. E. (2008). Culture and social support. American Psychologist, 63(3), 518–526.

Kim, J., & Zane, N. (2016). Help-seeking intentions among Asian American and white American students in psychological distress: Application of the health belief model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(3), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000056

Kim, J. E., Zane, N. W., & Blozis, S. A. (2012). Client predictors of short-term psychotherapy outcomes among Asian and white American outpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(12), 1287–1302.

Lam, A. G., & Zane, N. W. (2004). Ethnic differences in coping with interpersonal stressors: A test of self-construals as cultural mediators. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35(4), 446–459.

Lin, K. M., & Cheung, F. (1999). Mental health issues for Asian Americans. Psychiatric Services, 50(6), 774–780.

Lu, Y. E., Organista, K. C., Manzo, S., Jr., Wong, L., & Phung, J. (2001). Exploring dimensions of culturally sensitive clinical styles with Latinos. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 10(2), 45–66.

Maramba, G. G., & Nagayama Hall, G. C. (2002). Meta-analyses of ethnic match as a predictor of dropout, utilization, and level of functioning. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 8(3), 290–297.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253.

McGee, S. A., & Claudio, L. (2018). Nativity as a determinant of health disparities among children. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 20, 517–528.

McGuire, T. G., Alegria, M., Cook, B. L., Wells, K. B., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2006). Implementing the Institute of Medicine definition of disparities: An application to mental health care. Health Services Research, 41(5), 1979–2005.

Meredith, G. M. (1966). Amae and acculturation among Japanese-American college students in Hawaii. Journal of Social Psychology, 70, 171–180.

Meyer, O. L., & Zane, N. (2013). The influence of race and ethnicity in clients’ experiences of mental health treatment. Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 884–901.

Murase, T., & Johnson, F. (1974). Naikan, Morita, and Western psychotherapy: A comparison. Archives of General Psychiatry, 31(1), 121–128.

Park, S., Kim, J., & Zane, N. (2019). Effects of ethnicity, counseling expectations, and face concern on counseling style credibility and the working alliance. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Perez, J. E. (1999). Integration of cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal therapies for Latinos: An argument for technical eclecticism. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 29(3), 169–183.

Reimers, T. M., & Wacker, D. P. (1988). Parents’ ratings of the acceptability of behavioral treatment recommendations made in an outpatient clinic: A preliminary analysis of the influence of treatment effectiveness. Behavioral Disorders, 14(1), 7–15.

Sackett, D. L., Straus, S. E., Richardson, W. S., Rosenberg, W., & Haynes, R. B. (2000). Evidence based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM (2nd ed.). London, England: Churchill Livingstone.

Shon, S. P., & Ja, D. Y. (1982). Asian families. In M. McGoldrick, J. K. Pearce, & J. Giordano (Eds.), Ethnicity and family therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Snowden, L. R. (2001). Barriers to effective mental health services for African Americans. Mental Health Services Research, 3(4), 181–187.

Spielmans, G. I., & Flückiger, C. (2018). Moderators in psychotherapy meta-analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 28(3), 333–346.

Spring, B. (2007). Evidence-based practice in clinical psychology: What it is, why it matters; what you need to know. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63(7), 611–631.

Stiffman, A. R., Pescosolido, B., & Cabassa, L. J. (2004). Building a model to understand youth service access: The gateway provider model. Mental Health Services Research, 6(4), 189–198.

Sue, S. (1977). Community mental health services to minority groups: Some optimism, some pessimism. American Psychologist, 32, 616–624.

Sue, S., Fujino, D. C., Hu, L.-t., Takeuchi, D. T., & Zane, N. W. S. (1991). Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: A test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(4), 533–540.

Sue, S., & Morishima, J. K. (1982). The mental health of Asian Americans. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sue, S., & Zane, N. (1987). The role of culture and cultural techniques in psychotherapy: A critique and reformulation. American Psychologist, 42(1), 37–45.

The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (2007, October). The scientific rating scale. Retrieved from: https://www.cebc4cw.org/ratings/scientific-rating-scale/

Thompson, V. L. S., & Alexander, H. (2006). Therapists’ race and African American clients’ reactions to therapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 43(1), 99–110.

Whaley, A. L. (2001). Cultural mistrust and mental health services for African Americans: A review and meta-analysis. The Counseling Psychologist, 29(4), 513–531.

Wong, E. C., Kim, B. S. K., Zane, N. W. S., Kim, I. J., & Huang, J. S. (2003). Examining culturally based variables associated with ethnicity: Influences on credibility perceptions of empirically supported interventions. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9(1), 88–96.

Wong, E. C., Beutler, L. E., & Zane, N. (2007). Using mediators and moderators to test assumption underlying culturally sensitive therapies: An exploratory example. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 169–177.

Yang, L. H., Chen, F. P., Sia, K. J., Lam, J., Lam, K., Ngo, H., … Good, B. (2014). “What matters most:” a cultural mechanism moderating structural vulnerability and moral experience of mental illness stigma. Social Science & Medicine, 103, 84–93.

Zane, N., Kim, J., Bernal, G., & Gotuaco, C. (2016). Cultural adaptations in psychotherapy for ethnic minorities: Strategies for research on culturally informed evidence-based psychological practices. In N. Zane, G. Bernal, & F. Leong (Eds.), Evidence-based psychological practice with ethnic minorities: Culturally informed research and clinical strategies (pp. 169–198). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Zane, N., & Ku, H. (2014). Effects of ethnic match, gender match, acculturation, cultural identity, and face concern on self-disclosure in counseling for Asian Americans. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 5(1), 66–74.

Zane, N., Sue, S., Chang, J., Huang, L., Huang, J., Lowe, S., … Lee, E. (2005). Beyond ethnic match: Effects of client–therapist cognitive match in problem perception, coping orientation, and therapy goals on treatment outcomes. Journal of Community Psychology, 33(5), 569–585.

Zane, N., & Yeh, M. (2002). The use of culturally-based variables in assessment: Studies on loss of face. In K. S. Kurasaki, S. Okazaki, & S. Sue (Eds.), Asian American mental health (pp. 123–138). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Nishioka, S.A., Huang, C.Y., Zane, N. (2020). Friend or Foe: Empirically Supported Treatments for Culturally Minority Clients. In: Benuto, L.T., Gonzalez, F.R., Singer, J. (eds) Handbook of Cultural Factors in Behavioral Health. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32229-8_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32229-8_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-32228-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-32229-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)