Abstract

Old and new challenges with respect to farm income support, the environment and climate, and territorial imbalances justify a further reform of the common agricultural policy (CAP). As compared to the CAP post-2013 reform, the new CAP post-2020 proposals imply a rebalancing of the responsibility between the EU and member states (MSs), allowing more freedom with respect to measure implementation and design to MSs (subsidiarity). Moreover, it shows enhanced ambitions with respect to the environment and climate by again revising the green architecture as well as with respect to innovation. However, there are fears that a negotiated new CAP may not be ambitious enough and can induce member states to low target levels, even though there seems to be a wide consensus about the general CAP objectives.

This chapter is based on a study by the authors for the European Parliament with the aim to assess the proposals for the CAP after 2020. See Erjavic et al. (2018), García Azcárate (2018) and Jongeneel and Silvis (2018).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Challenges

Although the characteristics of the agricultural sector vary widely between member states, the main challenges are broadly the same: lagging farm incomes, increasing resource constraints (land and water) and environmental concerns (including climate), and changing consumer food preferences. In order to meet these challenges, economic viability and resource use efficiency of the sector require continuing attention. However, with respect to the EU, there are a number of specific challenges. Existing policy has a weak intervention logic and is poorly targeted, which leads to requests for Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) tailoring.

Several studies have assessed the main challenges with respect to the EU’s agriculture and food sector (e.g. Pe’er et al. 2017; European Court of Auditors 2018). Using the three main objectives of the current CAP (viable farms, sustainable management of natural resources (environment) and territorial balance) as a reference, the following main challenges can be identified:

1.1 Viable Farms

Farm income support is unequally distributed and poorly targeted. The main instrument used to support farm incomes is direct payments, which consume about 70% of the total CAP expenditure. In 2015, in the EU28 81% of the farmers received 20% of the direct payments (European Commission 2018a, b). Thus a large group of farmers receives a low amount of payments, whereas a small group receives a high amount of payments.

The share of direct payments in farm income varies considerably from about one-third for the lower-income classes to more than half of the higher-income classes (EU average is about 46%; EU Commission 2018b). The provided income support is thus progressive: farmers with relatively high incomes receive relatively high payments, which contrasts with the basic need for income-support principle (Terluin and Verhoog 2018).

To the extent that incomes of farms are supported for which there is less need for such income support, the inequality leads also to an ineffective use and a waste of scarce public resources. Moreover, it then raises land prices, and as such direct payments can be argued to create a barrier to entry for young farmers.

EU agriculture is frequently confronted with volatile prices, natural disasters, pests and diseases. The policy reforms leading to an increase in market orientation have not only created opportunities for EU agriculture to benefit from global markets, but also made the sector more vulnerable to international shocks and market disturbances. Price variability, which tends to outweigh yield variability, is an important factor contributing to the risks faced by farmers. The comparison of the periods 1997–2006 and 2007–2016 indicates that price variability increased for key arable products (cereals, oilseeds, potatoes), dairy products and beef (cows and bulls). Every year, at least 20% of farmers lose more than 30% of their income compared with the average of the last three years (EU Commission 2018b). However, in spite of the increasing need, in 2017, only 12 member states included one or more instruments of the risk management toolkit in their rural development programmes (RDPs), with the Italian, French and Romanian programmes accounting for a large proportion of total programmed public expenditures (Chartier et al. 2016).

1.2 Natural Resources

As regards the environment, for a long time the CAP has had a classical productivist orientation (Thompson 2017) and has led to high intensities of production in many sectors (e.g. livestock, which is in some regions very dependent on cheap imports of feed), thereby disturbing the agro-ecology and imposing an increasing pressure on the environment. Agriculture is a major source of nitrogen losses, with the current nitrogen loss estimated to be 6.5–8 million tonnes per year, which represents about 80% of reactive nitrogen emissions from all sources to the EU environment (Westhoek et al. 2015). These nitrogen losses take place mainly in the form of ammonia to the air, of nitrate to ground and surface waters and of nitrous oxide, a powerful greenhouse gas. Around 81–87% of the total emissions related to EU agriculture of ammonia, nitrate and nitrous oxide are related to livestock production (emissions related to feed production being included).

The nitrogen surplus on EU farmland (averaging 50 kg nitrogen/ha) has a negative impact on water quality. Since 1993, levels of nitrates have decreased in rivers, but not in groundwater. Nitrate concentrations are still high in some areas, leading to pollution in many lakes and rivers, mainly in regions with intensive agriculture (European Court of Auditors 2018).

Ammonia is an important air pollutant, with farming generating almost 95% of ammonia emissions in Europe. While emissions have decreased by 23% since 1990, they started to increase again in 2012 (ECA).

About 45% of mineral soils in the EU have low or very low organic carbon content (0–2%) and 45% have a medium content (2–6%). Soil trends are difficult to establish due to data gaps, but declining levels of organic carbon content contribute to declining soil fertility and can create risks of desertification.

As regards the climate, greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture accounted for 11% of EU emissions in 2015. These emissions decreased by 20% between 1990 and 2013, but started to rise again in 2014. Moreover, net removals from land use, land use change and forestry offset around 7% of all EU greenhouse gas emissions in 2015.

Whereas there are several measures deployed which are targeted to biodiversity and landscape, they are criticised for their limited effectiveness. According to the European Court of Auditors (2018), the conservation status of agricultural habitats was favourable in 11% of cases in the period 2007–2012, compared to less than 5% in the period 2001–2006. However, since 1990, populations of common farmland birds have decreased by 30% and of those of grassland butterflies by almost 50%.

1.3 Territorial Balance

In 2015, 119 million European citizens, representing almost a quarter of the EU population, were at risk of poverty and social exclusion. The average poverty rate is slightly higher in rural areas, with very contrasting situations across the Union as some countries display a huge poverty gap between rural and urban areas. Rural poverty, which appears to be less documented than urban poverty, is linked to the specific disadvantages of rural areas. These include an unfavourable demographic situation, a weaker labour market, limited access to education and also remoteness and rural isolation. The latter is associated with a lack of basic services such as healthcare and social services, and with increased costs for inhabitants on account of travel distances. These factors are considered to be the main drivers of rural poverty (EP Think tank 2017).

In terms of agriculture, it is argued that there is an investment gap which hinders restructuring, modernisation, diversification, uptake of new technologies, use of big data etc., thereby impacting on environmental sustainability, competitiveness and resilience. These bottlenecks also influence the ability to fully explore the potential of new rural value chains like clean energy, emerging bio-economy and the circular economy both in terms of growth and jobs and environmental sustainability (e.g. reduction of food waste). There are also consequences in terms of generational renewal in agriculture and more widely in terms of youth drain. Only 5.6% of all European farms are run by farmers younger than 35. Access to land, reflecting both land transfers and farm succession constraints, together with access to credit, are often cited as the two main constraints for young farmers and other new entrants (EU Commission 2018b).

2 The Proposed CAP Reform

2.1 Future of Food and Farming

In November 2017 the European Commission published the communication “The Future of food and farming” (European Commission 2017), which outlines the ideas of the European Commission on the future of the CAP. The general and specific objectives for the CAP after 2020 have been laid down in legislative proposals later in May 2018 (European Commission 2018a). The overarching declared principles are to make the CAP smarter, modern and sustainable, while simplifying its implementation and improving delivery on EU objectives. Key aspects of the proposals are the introduction of Strategic Plans, as well as the evidence-based approach and the stronger environmental focus.

2.2 Objectives

The general objectives of the future CAP according to the European Commission are:

-

To foster a smart, resilient and diversified agricultural sector ensuring food security

-

To bolster environmental care and climate action and to contribute to the environmental and climate objectives of the EU

-

To strengthen the socio-economic fabric of rural areas

These general objectives are further detailed into specific objectives, as these are presented in Fig. 14.1. When comparing these objectives with the current CAP, there is a near complete overlap, despite some rewording.

The CAP objectives will be complemented by the cross-cutting objective of modernising the sector by fostering and sharing of knowledge, innovation and digitalisation in agriculture and rural areas. Both the first pillar, agricultural income and market support, and the second pillar, rural development, contain instruments that aim to contribute to these general objectives.

2.3 Path Dependency in Direct Payment (Aids) Schemes

Path dependency is the main characteristic of the approach where in terms of measures no paradigmatic change is proposed. Not targeted farm income orientation is still the main characteristic with more manoeuvre for MS to select the types of direct payments. To ensure stability and predictability, income support will remain an essential part of the CAP. Part of this, basic payments will continue to be based on the farm’s size in hectares. However, the future CAP wants to prioritise small and medium-sized farms and encourage young farmers to join the profession. This is why the Commission proposes a higher level of support per hectare for small and medium-sized farms, proposes a capping of payments (with a limit on direct payments at €100,000 per farm), with a view to ensure a fairer distribution of payments. It also proposes a minimum of 2% of direct support payments allocated to each EU country to be set aside for young farmers, complemented by financial support under rural development and measures facilitating access to land and land transfers.

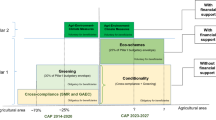

2.4 A New Green Architecture

In addition to the direct financial support, the new CAP claims to have a higher ambition on environmental and climate action (Matthews 2018b). The legislative proposals on the new CAP contain a new architecture for greening, which covers both pillars and consists of three components (i) enhanced conditionality; (ii) eco-scheme; and (iii) agri-environment, climate scheme and other management commitments (see Table 14.1 for a comparative overview).

Extended conditionality is the new word used for cross-compliance. The cross-compliance conditions are extended with respect to the current situation in that which are now the greening requirements (with the Green payment as a compensation) are proposed to be all included in the new cross-compliance.

Mandatory requirements following from the proposed “enhanced conditionality” include preserving carbon-rich soils through protection of wetlands and peatlands, obligatory nutrient management tool to improve water quality, reduce ammonia and nitrous oxide levels, and crop rotation instead of crop diversification. According to the proposal, farmers will have to comply with 16 statutory management requirements that relate to existing legislation with respect to climate and environment, public, animal and plant health and animal welfare. In addition, they have to follow ten standards for good agricultural and environmental condition of the land.

Farmers will have the possibility to contribute further and be rewarded for going beyond mandatory requirements. According to the proposal, EU countries will develop voluntary eco-schemes (offering at least one is obligatory) to support and incentivise farmers to observe agricultural practices beneficial for the climate and the environment (adoption by farmers is voluntary).

According to the proposal, the payments made for eco-scheme measures should take the form of an annual payment per eligible hectare, and they shall be granted as either payments additional “top up” to the basic income support, or as payments compensating beneficiaries for all or part of the additional costs incurred and income foregone as a result of the defined commitments. This allows member states to create a profit margin for farmers when participating in eco-schemes and could induce a wider spread adoption than in the case of agri-environmental and climate action schemes under Pillar II of the CAP (see Article 65). As such, eco-schemes can be a vehicle to, relative to Agri-Evironment and Climate Scheme (AECS), get a larger share of the farmers involved in pursuing lighter measures that are beneficent for the climate and environment.

2.5 Change of Policy Strategy

The European Commission proposes a flexible system, aimed to simplify and modernise the CAP. The emphasis is shifted from compliance and rules towards results and performance. Following the subsidiarity principle, member states get a more important role as they have to make national strategic plans, in which they set out how they intend to meet the nine EU-wide objectives using CAP instruments while responding to the specific needs of their farmers and rural communities.

3 Direct Payments and Rural Development Policy

3.1 Still Poor Targeting of Income Support

In the proposed CAP beyond 2020, direct payments will remain the core part of the interventions (measured in terms of budget spending) of the CAP in all member states. In terms of the type of interventions offered under the direct payments heading (first pillar of the CAP), probably the most notable change as compared to the current CAP is the new eco-schemes provision, which is part of the revised green architecture. The EU’s income support to farmers is suffering from inequalities in distribution of support, a lack of targeting and a lack of use of need-oriented criteria. The new CAP is likely to only address this problem to a limited extent, since the basic mechanism (hectare-based payments) is not changed (Jongeneel and Silvis 2018).

As regards the (voluntary) coupled income support, which is now labelled as “coupled income support for sustainability” this should be used in a targeted (or discriminatory) way rather than in a generic way, whereas otherwise it will distort the level playing field and go against the principle of the EU single market. The new proposal does not guarantee an improvement with respect to the current implementation practices.

The obligatory reduction of direct payments (capping) proposed by the EU Commission is, even in its proposed form, not likely to be very effective due to mandatory side condition to deduct the salaries of paid workers and imputed labour costs of unpaid labour (Matthews 2019). In the past, member states have often only adopted a rather weakened form of the capping schemes proposed by the Commission. Also with respect to this proposal, there seem to be already serious reservations by member states, which could easily lead to a further watering down of the Commission’s capping proposal (Petit 2019).

3.2 Greening via Enhanced Conditionality and Performance Schemes

The proposed new green architecture of the CAP implies a redefinition of the baseline, as this is comprised by the enhanced conditionality (Matthews 2018a). Grosso modo, the proposed new baseline includes the current baseline plus the current greening requirements (Jongeneel and Silvis 2018).

Member states have discretionary power to tailor the baseline to local conditions and preferences. On the one hand, this may tailor the baseline level better to local circumstances, but it may also lead to a divergence of baseline levels, as member states may make different decisions (e.g. with respect to the share of non-productive areas).

The enhanced conditionality contributes to establishing a baseline with respect to climate, environment, biodiversity and health, which goes beyond the current level. The extended greening requirements apply to all holdings receiving direct payments. Eco-schemes that are obligatory for member states and voluntary for farmers create possibilities to reward farmers for actions improving climate and the environment, which go beyond the baseline as established by the enhanced conditionality. Arguments are provided to further enlarge their potential and coverage.

As eco-scheme measures have to be complementary or additional to the baseline, both are related. The eco-scheme measures should also be different from those provided under the agri-environmental and climate action schemes of the second pillar of the CAP. As they are part of the first pillar of the CAP no co-financing by MS is needed. The eco-schemes allow member states to develop innovative schemes supporting climate and environment objectives, which go beyond mere flat rate payments (see Table 14.1) and allow for smart combinations of eco-schemes with AECSs.

As it has been emphasised by the Commission, the new CAP foresees an improved delivery model, including the strengthening of performance-based measures. Some member states have experience with such systems (e.g. Entry-Level Scheme of the UK) or are considering its potential (see the Public Goods Bonus scheme as this has been developed and proposed by the Deutscher Verband für Landschaftspflege (DVL 2017); also the Netherlands is considering a point-system type of approach). An important requirement of such performance-based schemes is to have reliable, simple and robust indicators (Dupraz and Guyomard 2019).

Such schemes would well fit in the philosophy of the new CAP (e.g. from compliance to performance or action to results; public funding for public goods principle) and have attractive properties (addressing the entrepreneurial rather than administrative qualities of farmers; rewarding farmers’ current efforts as well as offering farmers incentives to extend their environmental services to new areas of their farms; allowing farmers to offer an efficient mix of actions, or to “specialise” in the provision of specific public goods; offering flexibility to include a wide range of environmental services, including nutrient balancing and abstaining from artificial fertiliser use; and tailoring to regional conditions affecting agriculture, biodiversity and landscape). The proposal on the new CAP is vague in this respect, but should more explicitly stimulate performance or point-system approaches of eco-scheme implementations by member states, including “hybrid” schemes which involve simultaneously the public and private sectors (Jongeneel and Silvis 2018).

4 National CAP Strategic Planning

4.1 Strategic Planning

The proposed EC Regulation (COM (2018) 392) introduces comprehensive strategic planning at the MS level as one of the key new elements of the future CAP. The new delivery model may be seen as a step in the right direction, as this is the foundation of modern public policy governance. There will be also greater acceptance of the legitimacy of these policies.

The proposal draws on two precedents: the national strategy covering both CAP pillars foreseen in the fruit and vegetable regulation since 2006 and the model of strategic planning of rural development policy.

The CAP Strategic plans will presumably draw on analyses of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) and elaborations of needs in accordance with individual specific CAP goals (see above). In this regard, forming the environmental and climate objectives will have to take into account the relevant sectoral legislation, and special attention will be given to risk management. All needs addressed by the CAP Strategic plan will have to be described in detail, prioritised and their choice justified on the basis of the latest available and most reliable data. In the next step, the intervention logic will have to be determined for each specific goal. This means setting target values and benchmarks for all common and specific indicators and choosing and justifying the choice of instruments from the offered set based on sound intervention logic. The contribution of existing mechanisms will have to be considered (impact assessment of interventions so far), and comprehensiveness and conformity with goals in environmental and climate legislation will have to be demonstrated.

A review of the environmental and climate architecture of the strategic plan will have to be enclosed, as well as a review of interventions pertaining to the specific goal of generational renewal and facilitation of business development.

The mandatory elements of the CAP Strategic plans will contain overview tables with goals, measures and funding, a chapter on governance and coordination, a section on the Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems (AKIS) and digitalisation strategy, and enclosed will be the entire SWOT analysis, ex ante evaluation and description of the process and results of public consultation with stakeholders.

Strategic plans will be assessed by the Commission based on the completeness, the consistency, legal coherence, effectiveness and potential impacts of the proposals.

A concurrent review of the implementation of the CAP’s strategic plans will be carried out using annual reports in which MS will describe their progress through a system of output (referring to the implementation and use of finance) and outcome (referring to immediate result produced via application of a measure) indicators to be agreed at the Union level. In case of a more than 25% deviation from the respective milestone for the reporting year in question, the Commission may request the MS to draw up an action plan with corrective measures and the expected timeframe for their implementation.

Comparing the expected dynamics and quality of monitoring with existing rural development programmes, the proposed approach is more strategic and more result-oriented, demanding quick action and corrective measures in case of non-compliance.

4.2 Assessment of the Proposed Strategic Planning

The proposal gives some prospects for simplification, but essentially the governance system is not changed and contains all the shortcomings of the previous arrangements. The key question should therefore be how the proposed Strategic plans will be applied in the real world and whether it will bring about a more effective policy.

One of the key critics (Erjavec et al. 2018) is that the necessary accountability mechanism for strategic planning is weak. Limited accountability and ability to establish efficient intervention logic are serious gaps of the new delivery model. The current legal proposal does not frame the proposed CAP-specific objectives in a result-oriented manner. Three objectives relevant to the environment and their relating indicators are not directly linked to existing environmental legislation. The current proposals are also not clear on the method of quantifying the baseline situation. The study also questions the proposed exemption of background documents and analyses envisaged in the annexes of national strategic plans from the evaluation process.

Erjavec et al. (2018) mentioned that objectives should be quantified at the EU level and if associated legislation and objectives exist in other EU policies, these should be incorporated into the quantified definition of objectives in the CAP legal proposals. The legislative proposal requires a better demarcation of common EU and national objectives.

In principle, commonly defined should be those objectives that add value when implemented on a common scale, while the objectives where the principle of subsidiarity is more salient should remain at the national level.

The current system in designing measures is restrictive: Member states can only choose measures and adapt them. Moreover, some measures are compulsory in order to prevent renationalisation of policies and to achieve societal goals.

The process of strategic planning is left to the capacities and ingenuity of the member states, without guarantees that the performance at the EU level will be measurable as the national priorities emerge from SWOT analysis and may not necessarily reflect the EU-level priorities.

There are limited compelling incentives for member states to make efforts for better policies. The procedure related to the approval of the strategic plan is practically the only mechanism in the EC’s power for ensuring targeted and ambitious strategic planning. Therefore, it is of importance the Commission is empowered to make a proper qualitative assessment of the strategic plans (Erjavec et al. 2018).

CAP strategic plans should contain a satisfactory and balanced level of consultation between stakeholders and involvement of other public authorities, and that the Commission is well equipped to assess the plan within a reasonable period’s length. The adoption procedure should be more formalised, with the stakeholders’ opinions at the national level taken into account. This can improve the quality of the design and the legitimacy of the document.

As the approval by the Commission of the strategic plan will be the most important decision that the Commission will adopt, the current proposal represents a massive weakening of the institutional control capacity of the European parliament in the way the CAP is implemented. Therefore, the question remains of how to associate the European Parliament to this new decision process.

4.3 Risks of Strategic Planning at Member States Level

Striking a right balance between flexibility, subsidiarity, a level playing field at the EU level and policy control is a very complex task. Given that CAP funds have historically been based on a “measure by measure” approach, member states have little experience in programming various CAP instruments in an integrated way.

Developing planning and implementation capacities will be a major challenge for all member states, especially for small ones and those acceding EU after 2004. Empowering member states with greater subsidiarity may result in substantial administrative burden at the MS level.

For the member states with regional or federal legal organisation, the complexity of the internal negotiation of the contribution of each region to the achievement of the national and EU objectives should not be underestimated and could delay the real implementation of the new CAP.

Within chapter V of the proposed regulation (European Commission 2018b), the section on simplification is empty and left completely to MSs, which means that the Commission is leaving this at their discretion. The risks derive also from the varying capacity of actors in different member states. Flexibility may also be associated with risks of a departure from the pursuit of common goals at the EU level.

Therefore, the CAP proposals need to be accompanied by safeguards at the EU and MS levels, in particular by ensuring the effective engagement with civil society in both contributing to the design and monitoring the progress of strategic plans.

Without serious investment in personnel, processes, analytical support and inclusive preparation of Strategic plans, there may be considerable differences in policy implementation between individual member states. This could conceivably cause falling standards and negative trends in individual MS, which would in turn result in further weakening of the common policy.

4.4 Final Comments

The period 2021–2027 is a period of learning, in which the quality of data sources must be significantly increased, with systematic monitoring of the measures and their effects.

Both member states and EU bodies (JRC, EEA, Eurostat) have a role to play here. They see the utmost importance of strengthening the data sources related to needs analyses, and in particular, it is necessary to thoroughly reflect the appropriate data that will be employed as indicators for identifying and monitoring objectives. European Commission and member states need to be required to provide reputable and independent scientific and technical evidence to support their choices. This will require establishment of a common platform with an open access to all strategic plans, progress and evaluation reports.

5 Common Market Organisation

5.1 Marketing Standards and Rules on Farmers’ Cooperation Are Unchanged

As stated by the Commission in its presentation of the legislative proposals of June 2018, “the Common Market Organisation and its instruments remain largely unchanged”. The safety net continues to be composed of public intervention and private storage aid, on the one hand, and exceptional measures, on the other. Marketing standards and rules on farmers’ cooperation are unchanged. Nevertheless, the Commission underlines a “few important points for more effectiveness and simplification”:

-

The integration of sectoral interventions in the CAP plan regulation (for fruit and vegetables, wine, olive oil, hops and apiculture)

-

The extension of the possibility to initiate sectorial interventions to other agricultural sectors

-

Amendments to rules on geographical indications to make them more attractive and easier to manage

-

The adjustment of allocations following the multiannual financial framework (MFF) proposal

-

The deletion of a number of obsolete provisions

On the main issues related to the single common market organisation (CMO), the Commission has followed the Resolution of the European Parliament of 30 May 2018 on the future of food and farming (mentioned later on as “the Resolution”). The maintaining of the specific sectoral intervention has been also largely welcomed by the different stakeholders.

The European rules on producer organisations, their associations and the interbranch organisations deserve special attention. The first version of regulation 1308/2013 ended into a ceremony of the confusion. The same wording “producer organisation” was used in the same regulation with two significantly different meanings. The Omnibus regulation and the recent ruling of the European Court of Justice on the so-called endive case, represent important and positive steps in reducing the confusion and legal uncertainties.

5.2 Safety Net Provision

In the proposal for the future CAP, the current safety net system is continued. It is often argued that the current level of the European reference thresholds is “unrealistic” and does not contribute enough to achieve their safety net role. This argument has been, implicitly at least, partially accepted by the Commission when it increased withdrawal prices for many fruits and vegetables from 30% to 40% of the average EU market price over the last five years for free distribution (so-called charity withdrawals) and from 20% to 30% for withdrawals destined for other purposes (such as compost, animal feed, distillation).

In an increasingly market-oriented and open economy, such as the current European one, intervention prices cannot be related to production costs for, amongst others, two reasons. Firstly, there is no objective or unique “EU production cost” as such but rather a large range of production costs depending, for instance, on agronomic, climatic, farm and investments management, land prices, labour costs, national taxation systems and monetary factors. Secondly, too high intervention prices would stimulate EU imports of competitive products and discourage exports. Even more, they could stimulate increased production in third countries which could be exported to the EU.

Market orientation of the European agricultural sector and industry is one of the major achievements of the different waves of CAP reform. This is why EU agri-food trade surplus is at record levels (EC 2018a). This does not mean that, on a case-by-case basis, intervention (or withdrawal) prices could not be revisited. In some cases, they could be increased but in others, it could be the opposite. For instance, Jongeneel and Silvis (2018) concluded recently that “the intervention price level as it is currently defined for Skimmed Milk Powder (SMP) may need reconsideration and be in need to be lowered”.

5.3 Preventive Market Measures

Mahé and Bureau (2016) concluded that “the economics of market measures shows that they have the power to prevent or mitigate deep price disturbances, but when coming late they do not address properly the waste of productive and budget resources. Preventive policies look attractive at first glance, but their implementation raise political and institutional issues”.

Internal Commission rules and their corresponding Comitology make it practically impossible for the Commission to implement preventive measures despite the fact that these are more efficient and effective. Once the Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (DG AGRI) market unit is convinced that a potential problem is going to happen in a market, a time-consuming internal decision-making and consultation process starts (García Azcárate 2018).

After that, an official Interservice consultation is launched and a proposal is presented to, and voted by, the management committee if it is a Commission Regulation and approved by the Commission if it is a European Parliament and Council Regulation. Mahé and Bureau (2016) rightly assess “that the possibility, for all the three political institutions to interfere into details such as changing prices or volumes of intervention is not the best framework for good policy making”. They propose for that reason “an independent Administrative Authority for market measures”.

5.4 Crisis Management

Crisis management in the EU operates on a set of instruments and practices that are flexible enough to address a wide variety of needs arising from unforeseen extreme events. These tools can be found mainly in regulatory provisions for exceptional market support measures, market withdrawal, non-harvesting and green harvesting, as well as public interventions, private storage aid and incentives to supply reduction. The existing EU-level crisis management instruments are effective in addressing stakeholders’ needs to cope with crises (Ecorys-WUR 2019). They provide the necessary liquidity support to affected producers and reduce the need for ad hoc public aid. In addition, risk management tools constitute the first line of defence during a crisis, although the slow uptake of insurance, mutual funds and income stabilisation tools across the sector is identified as a potential gap in available crisis management responses.

In a context of increased globalisation and with a market-oriented policy, some crisis management instruments, such as public and private intervention, may have become less efficient. Derived from a long CAP history, measures related to supply and demand management are still one of the central parts of the crisis response strategy. In an open environment integrated with global markets, recourse to these measures may come at an increasingly high cost: crisis management by the EU indirectly benefits third country competitors, particularly for products where the EU is highly competitive on world markets. This may provide an argument for more international coordination with respect to market stabilisation (e.g. of the EU with key competitive suppliers) although feasibility might be a difficult issue. So far the current system and its funding have functioned reasonably well.

In the Commission’s proposal for a new CAP, a new agricultural reserve is proposed to be established under the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund. The amount of this reserve will be at least €400 million at the beginning of each financial year (including expenditure on public intervention and private storage), which compares to the current crisis reserve of €500 million. Unused crisis reserve amounts can roll over to the next year to constitute the new reserves. The new proposal aims at reducing the disincentive of not using the crisis reserve in case of a crisis (starting from 2020). With more and more budget constraints limiting the flexibility of reallocating CAP funds, it is not sure whether the newly proposed reserve approach will guarantee a well-functioning system in the future (lack of funding cannot be excluded).

5.5 Level Playing Field Needs Careful Attention

The interventions made available under Title III of the legal proposal for the future CAP offer member states a wide range of opportunities, the number and flexibility of which have been increased relative to those in the current CAP.

However, this runs the risk of increasing the differences in regulatory requirements and (compensating) support between member states. Level playing field concerns can be identified for at least three types of interventions: (1) the enhanced conditionality (potential differences in requirements over member states, combined with differences in basic income support for sustainability); (2) the payments for eco-schemes which can overcompensate the costs of efforts made; and (3) coupled income support. Also the sectoral interventions include aspects at the discretion of member states that can potentially distort the level playing field.

In order to avoid this, member states should be requested to motivate their choices and safeguards should be considered. In addition, the question remains if the Commission will be institutionally and politically strong enough to impose the common interest to any national “creative” measures which would disturb the single market, even if it comes from a big member states.

5.6 Rural Development Policy for Coping with Market Failure

The main change in the rural development policy is the new delivery model (from compliance to performance). With respect to its core principles and its coverage, it remains basically unchanged. The agri-environment, climate and other management commitments have a wide coverage (comprising measures contributing to all nine specific objectives of the CAP), with a special focus on environment and climate (obligatory).

Natural or other area-specific constraints and area-specific disadvantages resulting from certain mandatory requirements interventions contribute to fairness to farmers and are crucial policy interventions in an EU with very heterogeneous production and regulatory conditions.

The investment intervention possibilities in the proposed RDP plays a crucial role in helping agriculture to address its many challenges and facilitating the transition to a more sustainable agriculture while ensuring its long-term viability. When properly implemented, it should primarily address market failure (non-productive investments) and restore assets after crises. Its importance justifies introducing a minimum spending share requirement.

Investments and Young farmer support need a careful specification in order to ensure a level playing field and compatibility with WTO requirements. Risk management needs to be embedded in a broad approach (including awareness raising, farmer advice, accounting for interactions between various policy measures and private sector provisions) in order to contribute to a consistent, tailored and effective policy in which the proposed policy foresees.

Cooperation and knowledge- and information-sharing interventions, when properly combined with other interventions, play a key role in an effective innovation and farm modernisation strategy. The support and extension of the coverage of farm advisory services and its contribution to the improvement of agriculture’s sustainability are to be welcomed.

6 Concluding Remarks

There seems to be a wide consensus about the general policy objectives the CAP should pursue. Also the set of policy instruments that are proposed in the new CAP is not fundamentally different from the current CAP. Most significant are the proposed changes in the delivery model for the first pillar of the CAP, which should be more performance based and better be able to take into account the specifics of the member states.

The conceptual design of CAP Strategic planning at member state level is based on the theoretical concepts of policy cycle and evidence-based policy-making (EBPM). In real-world situations characterised by incomplete information and often conflicting policy goals, it is difficult for these two concepts to be fully realised. There are several reasons why decision-makers are not always able, or willing, to take evidence into account.

With respect to the policy, measures proposed under the new CAP as well as those with respect to the rural development policy remain largely unchanged. The most significant changes are with respect to the first pillar of the CAP, as a new green architecture is proposed (including eco-schemes as a new measure) and cross-compliance is extended into an enhanced conditionality including the current greening requirement now as standard baseline obligations.

The proposed legislation claims to be more ambitious with respect to improving the sustainability of EU agriculture, but there is still debate and uncertainty whether such a desired increased “value for money” will be finally realised (Dupraz and Guyomard 2019). The last discussion paper from the Presidency of the Council on CAP strategic plan, at the time this text was written (May 2019) clearly shows that the member states are moving in the direction of reducing the proposed ambition, limiting the commitments, increasing the flexibilities and decreasing the reporting obligations.

The increased implementation options at the member state level run the risk of distorting the level playing field in case of diverging ambition target levels between member states. In the Commission proposal, it was a potential risk. If the final result of the negotiation is close to what is today on the table of the Council, it could become a reality.

Also the measures of the CMO remain largely unchanged, although a new element is that member states will have the possibility (if they considerate necessary) to design operational programmes (otherwise called sectoral interventions) for other sectors than those that are already included in the existing regulation (fruit and vegetables, apiculture, wine, hops and olives).

References

Chartier, O., Cronin, E., Jongeneel, R., Hart, K., Zondag, M-J. and Bocci, M., eds. (2016). Mapping and Analysis of the Implementation of the CAP; Final Report. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/external-studies/2016/mapping-analysis-implementation-cap/fullrep_en.pdf

Dupraz, P., and H. Guyomard. 2019. Environment and Climate in the Common Agricultural Policy. EuroChoices 18 (1): 18–25.

DVL. 2017. Gemeinwohlprämie –Umweltleistungen der Landwirtschaft einen Preis geben; Konzept für eine zukunftsfähige Honorierung wirksamer Biodiversitäts-, Klima-, und Wasserschutz-leistungen in der Gemeinsamen EU-Agrarpolitik (GAP). Ansbach: Deutscher Verband für Landschaftspflege (DVL).

Ecorys-WUR. 2019. Improving Crisis Prevention and Management Criteria and Strategies in the Agricultural Sector; Final Report. Brussels: European Commission, DG-Agri.

EP Think tank. 2017. Rural Poverty in the European Union. Last Modified March 13. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2017)599333

Erjavec, E., M. Lovec, L. Juvančič, T. Šumrada, and I. Rac. 2018. Research for AGRI Committee – The CAP Strategic Plans Beyond 2020: Assessing the Architecture and Governance Issues in Order to Achieve the EU-Wide Objectives. Brussels: European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies.

European Commission. 2017. Report on the Distribution of Direct Payments to Agricultural Producers (Financial Year 2016). Brussells: European Commission.

———. 2018a. Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council. Brussels: European Commission, COM (2018) 392.

———. 2018b. The CAP 2021–2027; Legislative Proposal 2018; Questions and Answers. Brussels: European Commission, DG for Agriculture and Rural Development, Directorate C. Strategy, Simplification and Policy Analysis; C.1. Policy Perspectives.

European Court of Auditors. 2018. Future of the CAP; Briefing Paper. Luxembourg: European Union, March.

García Azcárate, T. 2018. Research for AGRI Committee – The Sectoral Approach in the CAP Beyond 2020 and Possible Options to Improve the EU Food Value Chain. Brussels: European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies.

Jongeneel, R., and H. Silvis. 2018. Research for AGRI Committee – Assessing the Future Structure of Direct Payments and the Rural Development Interventions in the Light of the EU Agricultural and Environmental Challenges. Brussels: European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies.

Mahé, L.P., and J.-C. Bureau. 2016. Research for Agri-Committee – CAP Reform Post 2020 – Challenges in Agriculture; Workshop Documentation. Brussels: European Parliament, Directorate-General; for Internal Policies; Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies.

Matthews, A. 2018a. The Greening Architecture in the New CAP. Blog-Post on June 20. http://capreform.eu/the-greening-architecture-in-the-new-cap/

———. 2018b. The Article 92 Commitment to Increased Ambition with Regard to Environmental- and Climate-Related Objectives. Blog-Post on June 30. http://capreform.eu/the-article-92-commitment-to-increased-ambition-with-regard-to-environmental-and-climate-related-objectives/

———. 2019. Capping Direct Payments – A Modest Proposal. Blog-Post on May 15. http://capreform.eu/

Pe’er, G., Y. Zinngrebe, F. Moreira, R. Müller, C. Sirami, G. Passoni, D. Clough, V. Bontzorlos, P. Bezák, A. Möckel, B. Hansjürgens, A. Lomba, S. Schindler, C. Schleyer, J. Schmidt, and S. Lakner. 2017. “Is the CAP Fit for Purpose? An Evidence-Based Fitness Check Assessment,” 1824. Leipzig: German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig.

Petit, M. 2019. Another Reform of the CAP; What to Expect? EuroChoices 18 (1): 34–39.

Terluin, I., and D. Verhoog. 2018. Verdeling van de toeslagen van de eerste pijler van het GLB over landbouwbedrijven in de EU. In Report 2018–039. Wageningen: WUR.

Thompson, P.B. 2017. The Spirit of the Soil: Agriculture and Environmental Ethics. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

Westhoek, H., J.P. Lesschen, A. Leip, T. Rood, S. Wagner, A. De Marco, D. Murphy-Bokern, C. Pallière, C.M. Howard, O. Oenema, and M.A. Sutton. 2015. Nitrogen on the Table: The Influence of Food Choices on Nitrogen Emissions and the European Environment (European Nitrogen Assessment Special Report on Nitrogen and Food). Edinburgh, UK: Centre for Ecology & Hydrology.

Websites

Direct Payments explained:

Cross compliance explained:

https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/direct-support/cross-compliance_en

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Jongeneel, R., Erjavec, E., García Azcárate, T., Silvis, H. (2019). Assessment of the Common Agricultural Policy After 2020. In: Dries, L., Heijman, W., Jongeneel, R., Purnhagen, K., Wesseler, J. (eds) EU Bioeconomy Economics and Policies: Volume I. Palgrave Advances in Bioeconomy: Economics and Policies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28634-7_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28634-7_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-28633-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-28634-7

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)