Abstract

This chapter examines affective factors in Chinese language study, at undergraduate university level, making use of a collation of data from three studies of motivation in this context. The teaching and learning of Chinese has been promoted in Australian schools and universities amidst the globalized spread of the teaching of Chinese as a second and foreign language. This aligns with the Australian government’s drive to produce ‘Asia-literate’ graduates, and puts pressure on educators to understand how to support the motivation of their students. The data presented in this chapter derived from three studies conducted respectively in 2011, 2013 and 2017. The studies reveal differences and similarities between heritage and non-heritage language learners. For both groups, learning Chinese for future job prospects features strongly, while for the heritage cohorts, familial heritage, cultural identity, and parental views all come into play to influence students’ choice of learning Chinese. Our studies also show that motivation factors may be shaped by changes in immigration patterns and social and political discourse.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Shifts in global power and employment opportunities, increasing mobility, and rediscovery of family heritage in diaspora communities, all contribute to shaping new reasons for people to study an additional language. Increased diversity within learner groups has also given rise to a more nuanced conceptualization of motivation constructs. With the growth of China’s economy and international outlook, and the growth of the Chinese diaspora, Chinese language learning has greatly expanded in many international contexts. This chapter briefly overviews current global interest in learning Chinese and the international research foci on teaching Chinese as a foreign language both in China and abroad, focusing particularly on the area of learner motivation. It is followed by an analysis of three case studies carried out in the Australian context against the background of fast development of teaching Chinese as a foreign language (CFL) in the past decade. The studies represent a progressive observation over a number of years of motivation in groups of tertiary Chinese language learners.

Chinese Language Education Internationally

The formal teaching of Chinese as a foreign language (CFL) began in the 1950s when basic Chinese language training was offered to some Eastern European exchange students at Qinghua University (Sun, 2009; Zhao, 2006). Chinese language courses were later extended to other universities in Beijing as more foreign students came to study short-term Chinese courses or to gain Chinese language proficiency in order to undertake formal university education in China. It was in the 1980s that CFL gained momentum after China opened its doors to the outside world (Sun, 2009; Zhao, 2006). Since then, there has been a steady increase of CFL programs across the country, with many universities offering short and long term CFL courses as well as bachelor and master degrees in CFLteacher training in recent years. Furthermore, driving the support of the growth of Chinese programs, there have been concerted efforts in China to train more qualified teachers of Chinese and to produce and disseminate resources, through Hanban (Chinese National Office for Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language) and the Confucius Institutes set up in various countries in recent years. In addition, Hanban annually trains and sends teachers and teaching assistants as volunteers to schools and universities in many different countries to solve teacher shortage problems. For example, by 2014, Hanban had sent over 30,000 volunteers to about 20 countries in Asia, Europe, America, Africa and Oceania (Xu & Moloney, 2015).

Internationally, the teaching of Chinese has expanded in many contexts as a result of perceived opportunities arising from the growing economic strength of China. As of 2014, there were about 100 countries with more than 2500 universities offering Chinese language subjects (Zhou, Liu, & Hong, 2014). The Chinese learning ‘fever’ has also seen a steady increase in learners of Chinese. According to an article by Cai and Wang (2017), by 2017, it is roughly estimated that there were more than 100 million learners of Chinese globally, among whom about 60 million leaners were overseas heritage leaners. In the US, for example, by 2015, there were Chinese programs in more than 550 elementary, junior high and senior high schools, while at the college level, enrolment in Chinese-language classes has increased 51% since 2002 (Shao, 2015). The growth in teaching of Chinese has also occurred in the UK where, by 2016, 13% of UK state schools and 46% of independent schools offered some form of Chinese study (BACS, n.d.). In other European contexts such as in Denmark, due to public interest in China within Danish society, Chinese language classes have been introduced into high school curricula as elective courses. In the last three years, more than one fifth of Danish high schools have begun offering Chinese classes.

Australia, with a large Chinese diaspora, has taken initiatives to support the learning of Chinese through the Federal Government’s policies and funding programs (Commonwealth of Australia, 2012). There is an increasing number of weekend Chinese community schools set up, and the number of students enrolled in Chinese courses at day schools has risen steadily. By 2016, there were about 170,000 students studying Chinese in more than 319 schools (Orton, 2016). The expansion can be observed in the tertiary sector, where the majority of universities and colleges offer Chinese programs. Although there is no recent estimate of tertiary Chinese language learners, the increasing rate of 60% between 2001 and 2006 (cf. White & Baldauf Jr, 2006) is a clear indication of an upward trend.

At the same time, while initial enrolments in courses are strong, there is also a high drop-out rate from school and university Chinese study. In the case of school study, of all students who commence Chinese study in primary or secondary schools, 96% have dropped out by senior secondary level (Orton, 2016). There is no equivalent data for university study, but we can observe anecdotally a significant drop in numbers between each year of undergraduate study. Thus the issue of motivation is a crucial one in sustainable Chinese language education, and a worthy object of research.

A Brief Overview of CFL Research

Chinese Context

After more than 60 years of practice and rapid growth, CFL has developed into a fully-fledged academic discipline (Xu & Moloney, 2015). Apart from the teaching and learning, it is also evidenced in robust research activities, including the emergence of a number of journals devoted to CFL research since the 80s. These include 汉语教学与研究 (Chinese Language Teaching and Research) (1979), 汉语教学 (Chinese Language Learning) (1980), 世界汉语教学 (Chinese Teaching in the World) (1987), 海外华文教育 (Overseas Chinese Education, 2000), 国际汉语教学 (International Chinese Education, 2009), 国际汉语教学研究 (Journal of International Chinese Teaching, 2014), to name but a few. Furthermore, the setting up of local and national research organizations, such as “the Language Teaching and Research Society of Beijing Language Institute” (1984) and “Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language Research Society of the Chinese Education Academy” (1983), further demonstrate an emerging CFL research agenda in China (Wang, Moloney, & Li, 2013; Zhao, 2006).

As a new area of study in the early 1980s, CFL research tended to adopt western second language acquisition theories and practice, focusing mainly on areas similar to EFL, such as error analysis, grammar and language acquisition. A search of extant literature on the development of CFL research in Chinese yields titles such as “On the development of research in interlanguage in CFL in the past 30 years”, “An analysis of research on error analysis in CFL in the past 30 years”, “A review of the research of pedagogy grammar of CFL since the 80s”. As noted, the 1990s witnessed even greater growth of CFL in China. It was at this stage that Chinese scholars began to take a strong interest in the motivation of learning Chinese. According to Gao (2013), early studies on ‘motivation’ were mainly of a descriptive nature, lacking a theoretical framework, scientific methodology design and in-depth analysis (Tan, 2015). However, with the continuing interest in the field (e.g., Wang, 2000; Feng, 2003; Gong, 2004; Zhang, 2008; Wang, 2011; Chen, 2012, among many others), many studies started to apply western motivation theories such as Gardner’s social psychological model (1985; see Gardner, this volume), using well known motivational constructs and survey instruments. For example, Fan’s (2015) review of some motivation studies in CFL in China states that for overseas students, instrumental, integrative, intrinsic and extrinsic motivations all come into play and influence learning in different ways: integrativemotivation is closely linked to intrinsicmotivation, which plays an important role in students’ early learning process. As their study deepens, extrinsic motivation relating to job prospects, further study, and a desire for increasing social status will also come into play. Shen’s study (2008) identified a further category—achievement motivation—while Guo (2009) found that for Indonesian students, there was also a ‘passivity’ factor, which refers to motivation coming from parental influence. That parents’ views have influenced students’ motivation for learning Chinese was also confirmed in another empirical study on South-East Asian learners of Chinese (Yuan, Shang, Yuan, & Yuan, 2008). Adapting Gardner’s Attitude and Motivation TestBattery (AMTB) (1985), their study identified seven important motivational factors: pedagogy factor, collaboration/competition factor, parent support factor, integrative factor, attitude towards foreign language and culture factor, study desire factor, and social responsibility factor.

Adopting the AMTB survey instrument, Yu’s (2010) study involved 215 learners of 25 nationalities at Beijing Language and Cultural University which has the largest CFL programs in China. The study investigated the interrelationships of affective variables and social and academic adaptation. The study points to a very positive and significant correlation between integrativemotivation and social, cultural and academic adaptation. It also found that two important measures of integrativemotivation, attitude towards the Chinese culture and interest in foreign language, are enhanced as an outcome of studying and also led to better language learning achievement. That motivation is a dynamic construct is echoed in Ding’s study (2015) which looks at what impacts on the strengthening of learner motivation over time. The study revealed three motivational factors: the students’ views on Chinese political, economic and language influence, their views on the bilateral relationship between their home country and China, and their interest in learning Chinese characters.

As CFL motivation study advances, Ding (2016) points out that CFL motivation research needs to employ more empirical methods in order to generate a more accurate picture of motivation types of learners of Chinese. She argues that this is because English and Chinese enjoy a different status in the world, so the types of motivation for learning English and learning Chinese must also be distinguished. Indeed, Dörnyei and Al-Hoorie (2017) hold the same view, suggesting that learner motivation for studying a language other than English (LOTE) is likely to be different from that of learning English. For example, LOTE learning may be more associated with highly specific and personalized reasons on the part of the learner. Departing from existing motivational constructs, Ding (2016) developed a questionnaire instrument from an initial open survey of 100 international students learning Chinese in a Chinese university in Beijing. The questionnaire had 30 statements and was administered to more than 620 students learning Chinese in the same university. A factor analysis identified five major factors of learning Chinese among the participants. These were, in order of importance:

-

1.

Career (e.g., ‘Chinese has to do with my work’; ‘Major in Chinese’)

-

2.

Opportunities (e.g., ‘Chinese political and economic influence’, ‘Learning Chinese brings new learning opportunities’, ‘Can find a good job’)

-

3.

Interest (e.g., ‘Interested in characters’, ‘Want to challenge myself’; ‘Like Chinese language and culture’)

-

4.

Learning Experience (e.g., ‘The influence of Chinese friends, teachers’; ‘Feels good when interacting with others in Chinese’)

-

5.

External influence (e.g., ‘Family has Chinese heritage’, ‘My peers are learning Chinese’; ‘Others suggest that I learn Chinese’).

The study also showed that for students of Japanese and Korean backgrounds, their motivational orientation is more geared towards instrumental types such as career advancement, while students of English-speaking backgrounds are studying Chinese because of intrinsicmotivation. This suggests that students of different cultural and linguistic backgrounds, while studying the same target language, may possess different motivational characteristics. Furthermore, as will be shown in the next section, there is also a major contextual variable influencing students’ learning motivation. That is, students coming to China to study Chinese may possess different motivation than those who are studying Chinese in their home country where Chinese is often studied as an elective towards a university degree. As such, motivation related to academic achievement is not uncommon (e.g., Wen, 1997).

International Contexts

There is growing recognition that each international CFL teaching context demands local pedagogical adaptation and diversification, in order to align with local expectations, to stem the drop-out rate and to achieve sustained motivation in young learners (Xu & Moloney, 2015). Against this background, a community of scholars is leading research in CFL, driven also by new understandings of foreign language teaching in the era of globalization (Kramsch, 2014). We acknowledge as a sample, a series published by the Chinese Language Teachers Association in America, including, Chinese Pedagogy: An Emerging field (McGinnis, 1996), Research among Learners of Chinese as a Foreign Language (Everson & Shen, 2010), and the collections of studies in the volumes by Tsung and Cruickshank (2011), Everson and Xiao (2011), and Zhou et al. (2014). Recent CFL publications have also focused on a wider range of topics such as teacherbeliefs, teacheridentities, application of technology, intercultural learning, and task based learning, reflecting new developments in CFL (e.g., Du & Kirkebæk, 2012; Jin & Dervin, 2017; Moloney & Xu, 2012, 2015, 2016, 2018; Ruan, Duan, & Du, 2015; Wang et al., 2013; Xu & Moloney, 2011a, 2011b).

In the past decade or so, there has been a rapid growth in Chinese education in international contexts, partly due to a steady increase of learners from Chinese-speaking migrant families. Referred to as heritage language learners (HLLs) (see Xu & Moloney, 2014a, 2014b), their growing presence in Chinese-as-a-foreign-language classrooms has attracted researchers interested in identifying learner motivations for the HLLs and non-HLLs, instantiated by studies such as those carried out in the US (see Lu & Li, 2008; Wen, 1997, 2011; Zhang & Slaughter-Defoe, 2009). Wen’s early study (1997) investigates the motivational factors of CFL students of Asian and Asian-American backgrounds in two US universities. The study incorporates expectancy-value theories in investigating how the relative attractiveness of learning outcomes, expectancies of learning ability and probability of obtaining the outcomes can influence the motivation of the students. The results of the study show that intrinsic interest in Chinese culture and the desire to understand one’s own cultural heritage are the initial motivation factor. Another motivating factor identified is ‘passivity’ which relates to course requirements. However, this is different from the construct found by Guo (2009, see above), which described ‘passivity’ relating to parental pressure. Wen’s study also shows that integrativemotivation is not a significant factor for students to continue learning Chinese, rather, the best predictor of eventual language attainment is the expectation of achieving a successful outcome, which generates more effortful learning. In a later study, Wen (2011) focuses on HLLs and non-HLLs, with the aim of investigating similarities and differences between the different learner groups. Using a number of theoretical frameworks such as Gardner’s social educational model (1985), the internal structure model of Csizér and Dörnyei (2005), and Weiner’s attribution theory (1985), the study was conducted with more than 300 students at three US universities. What the results show is the consistency of instrumentality as a powerful motivation, especially for heritage language learners (p. 57). This was observed also in a comparative study between HLLs and non-HLLs of Chinese language in a US college (Lu & Li, 2008), though it also found that integrativemotivation correlated more highly with both groups’ overall language scores. Wong and Xiao (2010, p. 172), using Bourdieu’s (1973) notion of ‘cultural capital’, have suggested that Chinese heritage language learners’ motivation is not merely connected with their past, but also with looking ahead; they view their Chinese linguistic ability as about “accumulating cultural capital in the globalized Chinese communities for their future” (p. 72).

In other multicultural contexts with large Chinese community diasporas such as Canada and Australia, there also have emerged a few studies on Chinese learner motivation, such as Comanaru and Noels’s study (2009) in the Canadian context and Xu and Moloney (2014a, 2014b) in Australia. Using the Self-Determination theoretical framework, Comanaru and Noels’s study investigates the social-psychological differences and similarities between HLLs and non-HLLs of university Chinese classes as well as HLL subgroups, namely, those who speak Chinese as the mother tongue and those who speak English. Their findings indicated that there were no motivational differences between the two groups of HLLs, while HLL groups did differ from non-HLL groups. For the HLLs, Chinese study was related to identity and that they felt familial pressure to learn Chinese. This pressure, similar to the findings of Wen (1997) and Guo (2009) (see above), may come either from parents or be a self-imposed obligation (p. 151).

In the Australian context, the authors have conducted a number of case studies, over a number of years, to survey students’ motivation for learning Chinese at their university, with the aim of finding out if HLLs and non-HLLs hold different motivational orientations and if, over time, there are changes in these motivational orientations. The rest of this chapter provides an overview of these studies. We next describe the methodology, present key findings, and draw out some theoretical and pedagogical implications.

Motivation of Australian Undergraduate Learners of Chinese

Methodology

Three small case studies were conducted in 2010, 2013 and 2017, within the Chinese Program at the researchers’ university. The participants were undergraduate students of Chinese between the ages of 18–25, most of whom are born in Australia and living with their parents, with a roughly even gender representation. While a small number of participants study Chinese as part of their major, most of them major in Commerce, Economics, Law, Education and International Studies, and choose Chinese as an elective. Motivation can be a key factor in choosing to continue to higher levels of Chinese studies.

While the three studies were carried out with different cohorts, they did share some common methodology. Each study featured a quantitative survey, which in addition to demographic information, elicited students’ motivational orientations to learning Chinese and their self-rated efforts and motivational level, on different Likert scales.

Results

Case Study 22.1

Our first study was conducted in the context of a Beginner mixed class of heritage language learners (HLLs) and non-heritage language learners (non-HLLs). At the time of the project, CFL enrolment had seen a noticeable increase in HLLs compared to non-HLLs. However, as it was a new phenomenon, and due to constraint of resources, there was only a mixed class offered. 44 first-year students of Chinese took part in the quantitative survey, which was part of a large internal departmental (of Researcher 1) survey to assess first year language students’ motivation and intention to continue into second year study. Some extra questions were added to the survey for Chinese learner participants to shed light on reasons for the rise of HLL enrolment. Of relevance to this chapter are three sections of the survey: students’ social and cultural background, reasons for studying Chinese, and self-reported motivational level. In terms of students’ social and linguistic background, over 40% of the students reported that they were born in a Chinese background family and 50% of the students responded that Chinese was an ancestral language of theirs, even though only about 27% said that Chinese was a home language. What this indicates is that although Chinese is not a day-to-day language at home for many students, it is a language recognized as spoken by either their grandparents or great grandparents or even ancestors dating back several generations

Figure 22.1 below shows the mean level of students’ responses to six statements about their motivation for studying Chinese. The statements have a Likert scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being Strongly Disagree and 5 being Strongly Agree. As can be seen, the most important reasons for both groups are ‘career prospect’ and ‘like the language and culture’. ‘Communicate with others’ is reasonably important for both groups, more so for the HLLs who also rated family heritage and societal expectation above the medium. For all the students, parents’ decision seemed the least important.

Motivation orientations for Studying Chinese (Case Study 22.1, N = 44)

In terms of students’ self-rated motivation level (5 represents ‘extremely motivated’, 4 ‘considerably motivated’, 3 ‘somewhat motivated’, 2 ‘not very much motivated’, 1 ‘not at all motivated’), the responses indicate that the mean motivation intensity of both the HLLs and non-HLLs was about 3, representing a middle range motivational intensity.

Case Study 22.2

By 2013, the percentage of HLLs in the Chinese Program of the researchers’ university had reached over 50% and more so in advanced level units, as more non-HLLs had dropped out (based on internal enrolment figures) due to reasons such as poorer performance or perceived disadvantage compared with the HLLs. Thus there was research interest in the motivation of the HLLs, and the second study was thus conducted with HLLs only, 44 students in all, including first, second and third year students. Our questionnaire had 14 statements covering a comprehensive range of motivation variables identified in existing literature, with Likert Scale responses (rated 1–5: 1 being Strongly Disagree and 5 being Strongly Agree). The results displayed in Fig. 22.2 show the mean ranking for each of the 14 statements

Motivation orientations for Heritage Students Studying Chinese (Case Study 22.2, N = 44)

If we consider only the values of each of the means, we can see that the first four orientations, which are related to ‘job prospects’ and ‘cultural heritage and identity’, have the highest scores (mean = 4 and above) while the two related to ‘study requirements’ received the lowest scores. In the middle, we can find a range of other motivation orientations: intrinsic (e.g., love the language), extrinsic reasons (e.g., travel), ‘social pressure’ (e.g., parents’ opinions, and external influence).

Factor Analysis was conducted to identify underlying influences that may contribute to the structure of motivation. The fourteen questions were exposed to a factor extraction and rotation process. Principal Axis factoring was used to extract factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0. Around 70% of the total variance was explained by four motivation factors, summarized in Table 22.1.

As ‘effort’ is an important component to show motivational intensity, we measured this by using two quantitative measurements: (a) whether students seek practice outside class, and (b) the number of hours spent practicing outside class. 86% of the students responded ‘Yes’ while 14% gave a negative response to question (a). The responses to question (b) showed that 46% of the students undertook between 1 and 3 hours, 26% of the students undertook 3–6 hours, 21% undertook between 1 and 3 hours, and only 7% spent 6 or more hours of outside study per week.

Another variable we measured was students’ self-rated motivational level. The data (mean = 3.6; median = 4) show that about 7% of students rated their motivation in the bottom two levels, 1 and 2, while the rest rated themselves 3 and above. The overall result shows that students believe themselves to be a reasonably well motivated group. It should be pointed out that as the second study consists of second- and third-year students whose continuing to the higher level can be a reflection of a higher motivational level, this may have elevated the motivational level of the entire cohort.

Case Study 22.3

The third case study was conducted in the first semester of 2017. Since 2013, due to increased HLL enrolment, a separate stream for HLLs has been set up at the Beginner level. In recent years, it was observed that the HLL group has become linguistically more diverse. A survey was conducted to help shed light on whether there were changes in the motivations for learning Chinese with a more diverse group. Of the total 24 students, as the survey was on a voluntary basis, only 18 returned the form, and of these, 6 were non-HLLs, but were Korean and Japanese students who had high prior Chinese proficiency due to previous study and were thus placed with the HLL stream. As these non-HLLs were too small in number to form a contrastive group and to produce any statistically significant result, they were removed from the data analysis, leaving the sample size for this study as 12. Although small in sample size, it was hoped that the data would still offer some indication of trends in students’ motivation. We used the same questionnaire as the second case study for this third one

Students’ demographic information confirms our observation that there are more diverse linguistic backgrounds in the student group, from previously mainly Cantonese to include Mandarin, Shanghainese, Southern Min, Hakka, and Fujian. It has showed a general increase of Mandarin speaking in the families, even though ancestors or grandparents might still speak other Chinese language varieties. Such a phenomenon is worth noting as it may have influenced students’ motivational orientations, as shown below.

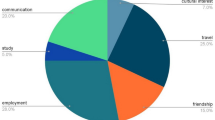

Figure 22.3 shows the means of the students’ responses to the questionnaire about their motivation for studying Chinese. Ratings were from 1 for ‘Strongly Disagree’ to 5 for ‘Strongly Agree’.

Motivation orientations for Heritage Students Studying Chinese (Case Study 22.3, N = 12)

If we consider the value of each of the means, we can see some slight changes in the ranking of the statements in terms of importance from the second study. Here, ‘cultural heritage’, ‘cultural identity’, and ‘parents’ opinions on own culture’ have the highest mean of 4.5 and above, while at the lower end are orientations to do with study, consistent with the second study. All the other orientations received mean scores in the middle range.

Again, a factor analysis was performed to identify underlying factors. The fourteen questions were exposed to a factor extraction and rotation process. Principal Components factoring was used to extract factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0. Just over 78% of the total variance were explained by four motivation factors. As noted above, we acknowledge the small sample size, unlike the second case study which, statistically, is sufficiently large to extrapolate to a broader population (Table 22.2).

Regarding the number of hours spent studying Chinese, as an indicator of motivational intensity, over 65% of the students reported to undertake between 1 and 3 hours, over 20% undertook 3–6 hours and less than 10% only undertook 1 hour of outside study per week. However, the result for self-rated motivation level shows that the students tend to rate their motivational level as high: the whole group rated themselves at least 3 out of 5 in terms of motivation level with half of these rated themselves 4 out of 5, but this is not reflected in their external study time. We discuss some reasons behind this in next section.

Discussion

The studies have revealed some interesting findings. Firstly, it was found that HLLs and Non-HLLs have some similar and some contrasting motivational orientations. This was shown in the study of the first mixed cohort. For both groups, the most important reason for taking up Chinese is future career prospects, more so for the non-HLLs. In the context of learning Chinese in 2010, this is understood as supported at that time by media and government policy discourse, as noted, and linked to external factors such as the political and economic influence of China and the perceived potential career advantages. This creates a favorable ‘milieu’ (Csizér & Dörnyei, 2005) which views Chinese as a means to an end. Both groups also displayed integrative orientations reflected in interest in the target language and culture, in love of foreign languages, and in learning Chinese for the purpose of communication. This demonstrates the students’ awareness of the need, in this increasingly globalized world, to be multilingual and multiculturally competent. However, given the importance of ‘career’ orientation to the students, to be able to communicate with others can also be interpreted as instrumental orientation, as it may indicate a desire to gain the language proficiency for job opportunities. With an expanding Chinese-speaking community in Australia, this also means the students wish to be able to speak Chinese in the work place and in social settings.

Secondly, the two studies that focused only on the HLLs show that studying Chinese for the benefit of future employment, be it the perception of the students themselves or their parents, continued to receive a very high rating, consistent with various studies reviewed above. While it is inappropriate to generalize with such a small sample, this is indicative of both the local and global perception of increasing opportunities arising in trade, tourism and cultural exchanges.

Thirdly, factor analysis of the last two studies shows some consistent underlying influences that may contribute to the structure of motivation of the two cohorts. Noticeably, both studies identified that heritage language culture and identity interact positively with integrative orientation such as liking the language and people, intrinsic orientation such as loving foreign languages, as well as with instrumental orientations such as pursuing future study, travel, and future employment. The positive association among these components is not difficult to understand. For example, while postgraduate study was ranked at the lowest end in terms of mean rating, for the HLLs, a future plan to pursue postgraduate study may constitute part of their strong interest and effort in achieving high proficiency in their heritage language. As for learning the heritage language for the purpose of travel, as shown in study 3, we have noted that recent HLL cohorts are children of the new generations of Chinese speaking migrants, most of whom come from mainland China. It is expected that there will be more frequent visits to their parents’ birthplaces and, as such, their interest in studying their heritage language naturally correlates with travel purpose. The two studies also confirm findings from studies conducted in China (see Ding, 2016; Yuan et al., 2008) that external influences, such as parental opinion, societal expectation and studying for credit points, play an important role in motivating HLLs’ study choice. As they are mostly first generation immigrants in Australia, with strong ties to their birth country and strong desire to maintain the heritage language and culture, parents may also have exercised their influence on the students’ decision and motivation for studying Chinese. Such a phenomenon was not as prevalent in the 2010 study.

The fourth finding shows that although engaged in such affective identity and strong career-related goals, the motivational level of both the HLLs and non-HLLs is middling, except the third cohort. It can be conjectured that as these students perceive Chinese as an advantage in the jobs market, and they do not wish to pursue postgraduate studies, an intermediate level will be adequate for functional communication, at work or within HLL families. The third study reveals a more complex picture: while rating themselves quite high on their motivational level, the effort they expended was less than the second cohort. Such a negative correlation can be for two reasons: the HLLs in the 2017 cohort are children of the new migrants who hold a very strong desire for their children to learn Mandarin Chinese, thus exerting much stronger influence on their children’s learning desire. Secondly, as the new generation of migrants are mainly from Mainland China and from families who speak Mandarin, the children have been exposed to more Mandarin in the home environment and so do not feel a strong necessity to exert greater effort to study. Furthermore, in the third study, travelling and post-graduate studies were found to be correlated with heritage and cultural identity components in the factor analysis. This could be because, for this 2017 HLL cohort with their parents’ closer connection with China, travelling to China and gaining a deeper knowledge of the heritage language and culture are a more important part of their identity.

Conclusion

This chapter has provided a brief review of international research into college students’ motivation to learn Chinese as a foreign language. The expansion of the teaching of Chinese, in the global context of the economic rise of China and the global mobility of peoples, is a response to diverse motivations. These include, but are not limited to, possible employment opportunities, travel, and reclamation of heritage language and culture in diaspora community families.

In common with other multicultural nations, Australia’s cities, homes and schools and university Chinese classes are diverse. Both non-HLLs and HLLs are valued by teachers and deserve equity of achievement. In the Chinese language classroom, teachers need understanding of all student needs and motivations, and how to maximize learning in the dual-level class. A data-informed understanding of motivation will assist teachers to design appropriate tasks and materials, stimulate enquiry, and actively support development in both the non-HLLs and HLLs.

In our work, following the first study, we have paid particular attention to HLL motivation, due to their increasing numbers in undergraduate classes. We would like to see more motivation research investigating the higher drop-out rate in non-HLLs. While government initiatives hope to create more young citizens with Chinese communicative abilities, regardless of background, it is the non-HLLs who particularly need encouragement to persevere in building their Chinese knowledge.

We have suggested, however, that both non-HLLs and HLLs have shifting profiles. Most are studying Chinese in the first instance for employment purposes, and opportunities both within and beyond Australia. However we note that both groups’ love of the language and culture also has to do with their lives in multilingual cities such as Sydney. The non-HLLs are studying with peers of Chinese origins, and mix socially with Chinese speaking workmates, friends, neighbors, all of whom have a shaping influence in motivation orientations.

Our three studies confirm that HLLs have a particular set of HL-related motivation factors, similar to studies involving HLLs reviewed above, but we also found that these factors are fluid, and can change. The motivation factors may be shaped by changes in immigration patterns and social and political discourse. We have noted the interplay between ‘heritage’ and ‘career’ motivation. We suggest that the career motivation may not be at odds with the family heritage motivation, but in some cases, congruent with it. Career choice and aspirations may be the focus of family encouragement, equally with family language communication issues. However, both of these two important motivational factors appear to operate in balance regardless of dialect, temporal distance from immigration, or degree of family linguistic abilities. We recall Wong and Xiao’s (2010) notion of heritage learners looking back and looking forward. This relationship was also evident in this study’s HL students. Their interest in their past linguistic and cultural heritage is balanced with a sense of their personal and professional future. For these students their motivation for Chinese study may be the connecting fulcrum between two areas of their life. Our findings also reinforce the view of Ding (2016), and Dörnyei and Al-Hoorie (2017) that learners’ motivation for studying a language other than English is, when freely chosen, associated with highly specific and personalized reasons. Our HLLs’ heritage-related motivational orientations are strong evidence.

We believe our study contributes questions, if not answers, to the emerging literature on CFL motivation. Australia is a CFL context which has explicitly supported Chinese study, has a well-developed pedagogy and resources, and the context relevance of a large Chinese diaspora. And yet it appears to still suffer from similar classroom motivation challenges as US, UK and European classrooms. The studies underline the need for differentiation in the body of motivation studies in Chinese language learning. If the growth of Chinese language study internationally is to be sustained, there is need for extensive future research studies in student motivation, how this may shift from context to context and over time, and the implications for pedagogy. Understanding this will be of ongoing importance to teachers, students and curriculum designers, in the global drive to strengthen the teaching and learning of Chinese.

References

BACS (n.d.) Chinese in UK Schools. Retrieved from http://bacsuk.org.uk/chinese-in-uk-schools

Bourdieu, P. (1973). Cultural reproduction and social reproduction. In R. K. Brown (Ed.), Knowledge, education and cultural change. London: Tavistock.

Cai, R. & Wang, Z. (2017). How popular is Chinese language study? The number of people learning to use Chinese language has exceeded 100 million. [柴如瑾,王忠耀(2017).汉语有多火?全球学习使用汉语人数已超一亿]. Retrieved from https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1842377

Chen, T. (2012). Research on the motivation of Thai and American students in non-target language environment. Language Teaching and Research. [陈天序 (2012). 非目的语环境下泰国与美国学生汉语学习动机研究. 语言教学与研究, (4), 30–37], 1(4), 30–37.

Comanaru, R., & Noels, K. A. (2009). Self-determination, motivation, and the learning of Chinese as a heritage language. Canadian Modern Language Review, 66(1), 131–158.

Commonwealth of Australia. (2012). Australia in the Asia century. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Csizér, K., & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The internal structure of language learning motivation and its relationship with language choice and learning effort. The Modern Language Journal, 89, 19–36.

Ding, A. (2015). Analysis on the changes of motivational orientations of students with increased Chinese language study intensity in non-target language environment. Applied Linguistics [丁安琪 (2015).目的语环境下汉语学习动机增强者动机变化分析. 语言文字应用, (2), 116–124.]

Ding, A. (2016). Analysis of motivational categories of overseas students of Chinese in China. Overseas Chinese language education. [丁安琪 (2016).来华留学生汉语学习动机类型分析. 海外华文教育, (3), 359–372.]

Dörnyei, Z., & AL-Hoorie, A. H. (2017). The motivational foundation of learning languages other than global English: Theoretical issues and research directions. The Modern Language Journal, 101(3), 455–468.

Du, X., & Kirkebæk, M. J. (2012). Exploring task-based PBL in Chinese teaching and learning. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Everson, M. E., & Shen, H. H. (2010). Research among learners of Chinese as a foreign language (4). Honolulu, HI: National Foreign Language Resource Centre.

Everson, M. E., & Xiao, Y. (2011). Teaching Chinese as a foreign language. Boston: Cheng & Tsui.

Fan, Y. (2015). On the important influence of motivation on Chinese language study of overseas students of Chinese. Journal of Chifeng College, 36(1), 255–256. [范亚杰. (2015). 试论学习动机对留学生汉语学习的重要影响. 赤峰学院学报. 36(1), 255–256].

Feng, X. (2003). Analysis on the study motivation of short term overseas students of Chinese. Journal of Yunnan Normal University., 1(2), 11–14. [冯小钉. (2003) 短期留学生学习动机的调查分析. 云南师范大学学报- 对外汉语教学与研究版, 1(2), 11–14].

Gao, Y. (2013). A review of research of Chinese language study motivation in China in the past twenty years. Journal of Yunnan Normal University, 11(5), 26–33. [高媛媛. (2013). 国 内近二十年来汉语学习动机研究述评. 云南师范大学学报: 对外汉语教学与研究版 11, no. 5, 26–33].

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Gong, Y. (2004). Research on Chinese language learning motivation of Japanese students. Unpublished MA Thesis. Beijing Foreign Language Study University. [龚莺日 (2004). 日本学生汉语学习动机研究. 北京语言大学硕士学位论文].

Guo, Y. (2009). On Chinese language learning motivation of Indonesian overseas students of Chinese. Unpublished MA thesis, Xiamen University. [郭亚萍 (2009). 印尼留学生汉语学习动机调查研究. 厦门大学,硕士论文].

Jin, T., & Dervin, F. (Eds.). (2017). Interculturality in Chinese language education. New York: Springer.

Kramsch, C. (2014). Teaching foreign languages in an era of globalization: Introduction. The Modern Language Journal, 98(1), 296–311.

Lu, X., & Li, G. (2008). Motivation and achievement in Chinese language learning: A comparative analysis. In A. Weiyun He & X. Yun (Eds.), Chinese as a heritage language: Fostering rooted world citizenry. Hawaii: University of Hawaii, National Foreign Language Resource Center.

McGinnis, S. (Ed.). (1996). Chinese pedagogy: An emerging field. Chinese language teachers association monograph No. 2 and pathways to advanced skills (Vol. 11). Columbus: National Foreign Language Resource Center, At the Ohio State University, and the Ohio State University Foreign Language Publications.

Moloney, R., & Xu, H. L. (2012). “We are not teaching Chinese kids in Chinese context. We are teaching Australian kids”: Mapping the beliefs of teachers of Chinese language in Australian schools. In Culture in foreign language learning: Framing and reframing the issue (pp. 470–487). Singapore: National University of Singapore Centre for Language Studies.

Moloney, R., & Xu, H. L. (2015). Transitioning beliefs in teachers of Chinese as a foreign language: An Australian case study. Cogent Education, 2, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2015.102496

Moloney, R., & Xu, H. L. (2016). Exploring innovative pedagogy for the teaching of Chinese as a foreign language. New York: Springer.

Moloney, R., & Xu, H. L. (2018). Teaching and learning Chinese in schools: Case studies in quality language education. Palgrave Pivot.

Orton, J. (2016). Building Chinese language capacity in Australia. Sydney: Australia-China Relations Institute (ACRI).

Ruan, Y., Duan, X., & Du, X. Y. (2015). Tasks and learner motivation in learning Chinese as a foreign language. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 28(2), 170–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2015.1032303

Shao, G. (2015). Chinese as a second language growing in popularity. Retrieved from https://america.cgtn.com/2015/03

Shen, Y. (2008). On the relationship between Chinese language learning motivation and study strategies of overseas students of Chinese. Unpublished MA thesis, Shanghai Jiaotong University. [沈亚丽. (2008). 来华留学生汉语学习动机与学习策略及其相关性研究. 上海交通大学硕士论文.]

Sun, D. (2009). An overview of research and teaching of Chinese language as a foreign language. Language Teaching and Linguistic Studies, (2), 45–53. [孙德金. (2009) 五十余年对外汉语教学研究纵览. 语言教学与研究,(2), 45–53.]

Tan, X. (2015). A review of research studies on Chinese language learning motivation in China and abroad in the past 30 years. Journal of Kunming Ligong University. [谭晓健. (2015) 国内外 30 年来汉语学习动机研究述评. 昆明理工大学学报 (社会科学版), 94–101].

Tsung, L., & Cruickshank, K. (Eds.). (2011). Teaching and learning Chinese in global contexts: CFL worldwide. London: Continuum.

Wang, A. (2000). Cultural identity and Chinese language learning motivation of overseas students from Southeast Asia. Journal of Overseas Chinese University. [王爱平. (2000). 东南亚华裔学生的文化认同与汉语学习动机. 华侨大学学报: 哲学社会科学版 3: 67–71.]

Wang, D., Moloney, R., & Li, Z. (2013). Towards Internationalising the curriculum: A case study of Chinese language teacher education programs in China and Australia. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(9), 8. Retrieved from http://ro.ecu.edu.au/ajte/vol38/iss9/8

Wang, E. (2011). Development of research in motivation to learn Chinese. Higher Education Forum. [王恩界. (2011). 对外汉语学习动机的研究进展. 高教论坛, (10), 135-137.]

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548.

Wen, X. (1997). Motivation and language learning with students of Chinese. Foreign Language Annals, 30(2), 235–251.

Wen, X. (2011). Chinese language learning motivation: A comparative study of heritage and non-heritage learners. Heritage Language Journal, 8(3), 41–66.

White, P., & Baldauf Jr., R. B. (2006). Re-examining Australia’s tertiary language programs: A five year retrospective on teaching and collaboration. St Lucia, QLD, Australia: Collaborative Structural Reform Research Project, UQ.

Wong, K. F., & Xiao, Y. (2010). Diversity and difference: Identity issues of Chinese heritage language learners from dialect backgrounds. Heritage Language Journal, 7(2), 152–187.

Xu, H. L., & Moloney, R. (2011a). Perceptions of interactive whiteboard pedagogy in the teaching of Chinese language. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(2), 307–325.

Xu, H.L. & Moloney, R. (2011b). “It makes the whole learning experience better”: Student feedback on the use of the interactive whiteboard in learning Chinese at tertiary level. Asian Social Science (November Special edition).

Xu, H. L., & Moloney, R. (2014a). Identifying Chinese heritage learners’ motivations, learning needs and learning goals: A case study of a cohort of heritage learners in an Australian university. Language Learning in Higher Education, 4(2), 365–393,. ISSN (Online) 2191-6128, ISSN (Print) 2191-611X. https://doi.org/10.1515/cercles-2014-0020

Xu, H. L., & Moloney, R. (2014b). Are they more the same or different? A case study of the diversity of Chinese learners in a mixed class at an Australian university. In S. M. Zhou, G. Q. Liu, & L. J. Hong (Eds.), Teaching Chinese: Challenges in a globalized world (pp. 176–216). Shanghai, China: Fundan University Press.

Xu, H. L., & Moloney, R. (2015). Tapping into Teachers’ practical knowledge as a foundation of innovative practice: Narratives of international experience from Chinese CFL teachers. In R. Moloney & H. L. Xu (Eds.), Exploring innovative pedagogy for the teaching of Chinese as a foreign language. Cham: Springer.

Yu, B. H. (2010). Learning Chinese abroad: The role of language attitudes and motivation in the adaptation of international students in China. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 31(3), 301–321.

Yuan, Y., Shang, Y., Yuan, Y., & Yuan, K. (2008). Empirical research on the Chinese learning motivation and attitude of southeast Asian overseas students. Journal of Yunnan University, 6(3), 46–52. [原一川,尚云,袁炎,袁开春. (2008). 东南亚留学生汉语学习态度和动机实证研究. 云南师范大学学报, 6(3), 46–52].

Zhang, D., & Slaughter-Defoe, D. T. (2009). Language attitudes and heritage language maintenance among Chinese immigrant families in the USA. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 22(2), 77–93.

Zhang, K. (2008). On Chinese language learning motivation of overseas students and teaching strategies. Journal of Higher Correspondence Education, 21(4), 64–65. [张柯. (2008). 试论外国留学生的汉语学习动机与教学策略. 高等函授學報 (哲社版), 21(4), 64–65].

Zhao, J. (2006). From Chinese language education to internalization of Chinese education. Foreword, Chinese language education and research. [赵金铭. (2006).从对外汉语教学到汉语国际推广 (代序). 赵金铭,李泉. 对外汉语教学研究. 北京: 商务印书馆.]

Zhou, S. M., Liu, G. Q., & Hong, L. J. (Eds.). (2014). Teaching Chinese: Challenges in a globalized world. Fudan: University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Xu, H.L., Moloney, R. (2019). Motivation for Learning Chinese in the Australian Context: A Research Focus on Tertiary Students. In: Lamb, M., Csizér, K., Henry, A., Ryan, S. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Motivation for Language Learning. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28380-3_22

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28380-3_22

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-28379-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-28380-3

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)