Abstract

Global trends in higher education which have seen increased research student enrolments have also brought growing uncertainty around employment outcomes, now encompassing both academia and industry (Jones, 2018). Related research has largely focused on the products of student work and the experience of supervision, with student voices often unnoticed, overlooked or unobserved. Through foregrounding student voices, this chapter explores the impact of relationships on the experience of negotiating academic culture and preparing for life, post-graduation. Linking our data to the leitmotifs of Dr. Seuss’ ‘Oh the places you’ll go’, themes emerged representing the highs, lows, uncertainties and unknowns inherent in their experience of academia and the relationships which sustain them. Data was viewed through the lens of identity theory (Whannell & Whannell, 2015), using a narrative approach (Crotty, 1998) and gathered from an anonymous survey of research students and recent graduates across universities in 15 countries (N = 425). Findings highlight students’ rich experiences and perceptions across the postgraduate research process, with attention given to the relationships that enabled or constrained their identity formation and sense of belonging. Whilst there was great diversity amongst the participants, there were surprising consistencies, particularly the significant impact of the quality of social interaction on identity and notions of belonging.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The profile of the ‘postgraduate research student’ has undergone enormous change, in part due to global trends toward increasing enrolments, bolstered by university advertising campaigns and government policy (Norton & Cherastidtham, 2014). Postgraduate research studentsFootnote 1 are faced with changing and more stringent requirements focusing on ‘higher level development of advanced practitioners’ (Fillery-Travis & Robinson, 2018, p. 841). These candidates increasingly have expert knowledge of practice in their field, which can exceed that of their supervisors (Jones, 2018). This progressive shift is reflected in changing demographics, with incoming students characterised by their diversity in age, background, culture, experience, professional standing and desired career outcomes (Becker et al., 2018; Boud et al., 2018; Fillery-Travis & Robinson, 2018; Jones, 2018; Lee, 2018; UA, 2015). However, with the exponential rise in enrolments comes uncertainty around what these research degrees prepare students for, particularly as a future in academia can no longer be guaranteed (Lundsteen, 2014; Marsh & Western, 2016).

Literature surrounding research student experience focuses largely on the outputs or products of student work and the experience of supervision. In these, student voices are often unnoticed, overlooked or unobserved in the very literature that was written in support of them. As if in answer to this silence, there has sprung up a plethora of social media highlighting research student voices (such as The Thesis Whisperer, PhD talk, #phdchat). The significance of relationship-development to the research degree process, is often also less or un-acknowledged, as institutionally, the process is flagged by ‘measurable’ milestones leading to completion. In this chapter, we focus on how relationships impact student experience as they negotiate and position themselves in academic culture during their study period and when considering their futures, thus bringing together academic investigation and students’ voices. As early career academics ourselves we have a keen interest (and recent memory) of how the path of employable scholars is trekked. We found much affiliation with the leitmotifs of Dr. Seuss’ (1957) Oh, the places you’ll go: the highs, lows, challenges, uncertainties and unknowns. So, also, did the themes which emerged from the words of our participants, offering insights into a diverse range of experiences of academia and those relationships which sustained them (or not). A review of the literature in the next section focuses on some of the implications of the changing nature of the research degree.

2 Oh, the Places We’ve Been…A Literature Review

The research degree process could be described in functional terms as a series of transition periods—flagged by milestones such as course completion, research proposal, data collection, writing up, full draft and so on—which tend to move from more to less structured support. Thus, students are constantly adapting as they navigate from high structural support in the early stages towards becoming an ‘expert.’ During these times of transition, relationships are often key to how students move into emerging roles, perceptions of self and levels of persistence to succeed in their research degrees (Baker & Pifer, 2011; Whannell & Whannell, 2015). While the outputs of study proposal and thesis are clearly foregrounded, many implicit expectations are rarely discussed and often left for the students themselves to discover and negotiate, often in isolation (Jones, 2018; Lundsteen, 2014). Thus, aside from the research topic, supervisor-student and peer relationships are significant, particularly in the murky area of bridging the unknown to known, and is an important part of the enculturation and identity forming processes.

Although full time research degrees are still the main path chosen ‘by those yet to start their working life’ (Boud et al., 2018, p. 915), the shift towards practitioner-focused research degrees has ushered in a change in the demographic characteristics of these students, thereby diversifying the cohort (Fillery-Travis & Robinson, 2018; Lee, 2018). This, in part, is reflective of institutions seeking to meet the demands of employers, but also to attract a share of international student market (Jones, 2018). According to Becker et al. (2018) employers are seeking graduates who are able to make connections with the ‘deep vertical knowledge’ in their particular domain, together with a broad set of soft skills such as ‘teamwork, communications, facility with data and technology, an appreciation of diverse cultures, and advanced literacy skills’ (p. 18). This demand for employability outside of the academy brings new challenges to supervisors, particularly if their supervision style is more traditional or if they themselves have not worked elsewhere. A student entering a research degree with a high level of expertise in their field requires a different kind of supervisory approach to those who rely on their supervisors for expert input, or to those who have had an uninterrupted progression from school to undergraduate to postgraduate study. Thus, the complexity of diversity at many levels, gives rise to the potential for mismatching expectations, particularly in the supervisory relationship.

Relationships, both within and outside of the academic community seem to become more important during the period of the degree where there is less structured support, and where students may experience a sense of isolation (Baker & Pifer, 2011, p. 9). Baker and Pifer (2011) argue that because these stages are ‘unlike any other professional or educational experience’ (p. 8) relationships become paramount to helping students navigate basic challenges associated with becoming autonomous, developing a high level of expertise and negotiating identities. During this period, the role of peers is invaluable for modelling socialization as ‘agents of community, learning, and development’ (Flores-Scott & Nerad, 2012, p. 76). As such, peer relationships can be multi-faceted, encompassing how students ‘learn the values, skills, and norms of their discipline or field’ as well as provide ‘emotional support, general advisement, and specific content knowledge’ (p. 76) and how they ‘teach each other the practices of research and scholarship’ (p. 79).

The changing nature of the research degree also highlights the reality that this qualification is no longer a natural progression into academic employment. While the goal of postgraduate research programs is ‘to socialize students into academia [and] prepare students to become researchers and faculty members’ through supportive relationships (Rogers-Shaw & Carr-Chellman, 2018, p. 236), the high numbers of students being admitted into degrees precludes any assurance of an academic career path (Jones, 2018; Lundsteen, 2014). As Lundsteen points out, the academic landscape is shifting, and students even though learning to become researchers may have little option but to consider non-academic pathways after completion. This uncertainty however, highlights the crucial role of relationship development throughout the doctoral degree, particularly for future employability. Doing a research degree is often a solitary experience (Jones, 2018), and it may not be made explicit that skills learnt in becoming part of an academic community are transferrable to and desirable for future contexts such as industry employment. Some valuable skills include problem-solving and solutions, working collaboratively, and communicating effectively (Rogers-Shaw & Carr-Chellman, 2018).

We argue that relationships are important shapers of the research experience. To explore the impact of relationships this chapter adopts Lee’s (2018) framework of supervisory practices to focus on relational aspects, guided by five themes: functional, enculturation, critical thinking, emancipation and relationship development (explained in the data analysis section). We examine supervisor and peer relationships only but acknowledge that these are not the only relationships that sustain students. The next section outlines the theoretical approach taken.

3 Theoretical Approach

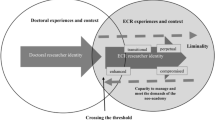

To explore how relationships impact students’ changing identities and perceptions of belonging, we use the lens of identity theory (Whannell & Whannell, 2015). The voices of students are foregrounded using a narrative approach, addressing the gap between the ‘measurable’ and student experience. Identity formation as a social construct is dynamic, emergent and dependent on opportunities afforded through ongoing socially-negotiated relationships and interaction (Gee, 2000; Knowles, et al., 2012). We draw on Whannell and Whannell’s (2015) University Student Identity Theoretical Model to understand how research students construct a multiplicity of identities, dependent on three factors working together within the social context of academia. These factors are Student Identity, Student Role and Emotional Commitment. Whannell and Whannell (2015) explain that perceptions of ‘successful’ academic engagement (or otherwise) will influence students’ sense of worthiness (identity) and thus their academic behaviours (role), which in turn influences the level of emotional commitment, associated with student identity. Separating the student role (i.e. what they do) from the student identities (who they are) enables a way of understanding the impact of relationships that form during a research degree. The relationships most mentioned in our data are with supervisors, peers and other academics. Sense of worthiness (identity), academic behaviours (role), and emotional commitment are understood within the social context of these relationships.

The focus of qualitative research is to harness theory in order to open up social contexts and relationships to a deeper richer view (Crotty, 1998). Stone and O’Shea (2012) state, ‘one of the best ways to understand the actions of individuals is to be allowed to hear their personal stories as they themselves choose to narrate them’ (p. 2). Therefore, a narrative approach has been adopted in this research to reveal students’ stories, fluid and altering, highlighting themes of belonging, identity formation and role through their stories of every day lived experience, noting conflicts and complexities (Andrews, Squire & Tamboukou, 2008). Such research reveals ‘the deep, layered and multifaceted lives of the participants’ (Harden-Thew, 2014, p. 71), the ‘messiness’ of their experience (Spyrou, 2011).

4 Methodology

Data was gathered from an anonymous survey of research degree students and recent graduates (N = 425Footnote 2). Following ethics approval from the University of Wollongong, the survey link was sent electronically firstly within Australia and then via various networks and social media between March and July 2018. Respondents were spread across 15 different countries from 98 different institutions studying within a range of disciplines, including humanities and arts, natural sciences (physical, earth, life, medical and health), computer science, mathematics, business and marketing, education, engineering, law and theology. The survey gathered demographic information as well as stage of degree, and student status. The qualitative section included questions about milestones, experiences of supervision and peer relationships, hurdles/barriers, goals, support and how well students perceived they were ‘finding their place’. These questions were partly informed by the University Student Identity Theoretical Model (Whannell & Whannell, 2015), focusing on relationships and perceptions of successful academic engagement; emotions and perceptions of milestones in terms of ‘worthiness’ and academic behaviours; and the role of relationships on forming student identity(ies). The narrative approach utilised enables student voices to be foregrounded.

4.1 Participants

The diversity within the participants is clear from the demographic information they provided. The majority were female (75%, n = 319), and 23% were male (n = 98) with some preferring not to indicate gender. Almost two-thirds were in the age ranges of 21–29 and 30–39 years (32%, n = 135; 30%, n = 125 respectively). Those who were 40–49 and over 50 years together represented 37% (18%, n = 78; 19%, n = 79 respectively), with twenty being in their 60s and four in their 70s. The youngest was 22 years and the oldest, 74. Of the total, 253 said they had a break in formal study before commencing their research degree, with the length of time varying from 6 months or less (4%, n = 9); 1 to 3 years (46%, n = 116); 4 to 5 years (15%, n = 37) and 6 to 10 years (19%, n = 48). The remainder indicated they had a break of more than 11 years (17%, n = 43), which included four who had a lengthy break of 30–35 years. Most indicated they were domestic students (81%, n = 346), with 74 being international. English is the first language of the majority (82%, n = 348), with 77 indicating first languages other than English (18%) and 36 different first languages named.

All stages of the postgraduate research process were represented—from pre-proposal to recent graduate. Most respondents indicated they were in the data collection/analysis phase and/or writing chapters or publications phase. Table 18.1 summarises this data.

Almost a third said they were part-time, with a small percentage varying between full and part-time at different stages of their candidature. 320 (75%) were enrolled as on-campus students, while 82 (19%) were distance, with some moving between on-campus and distance status over their candidature. Others, although enrolled as on-campus, only attended for supervisory or other meetings, or they were based elsewhere (such as an external research site or satellite campus).

5 Data Analysis

Lee’s (2018) framework for analysing the impact of supervisory relationships was used to gain a deeper understanding of the conditions under which such relationships developed, either positive or negative. Five themes comprise the framework developed from supervisor perspectives of the ‘essence of the modern doctorate’ (Lee, 2018, p. 882) (Table 18.2). This framework enabled us to code student perspectives of their supervisor and peer relationships. In preparation, each response was allocated a respondent number with a small sample of the dataset coded first according to Lee’s framework and imported into NVivo11 for sentence by sentence coding and then applied to the whole dataset. From this process, a sub-theme emerged, and was added to Relationship development: co-location.

6 Findings

While there was great diversity amongst the participants, identity formation was surprisingly consistent. Using Lee’s five themes as a guide, we analysed the comments from two of the survey questions on supervisor relationships and peer relationships: (1) What have been your experiences with establishing supervision relationships? (2) What kinds of relationships have you developed with your study peers? In total 316 students provided qualitative comments.

6.1 Supervisor Relationships

The qualitative data for the five themes yielded a total of 404 coded instances which provided insight into how students perceived the relationships with their supervisor/s. In order of frequency, relationship development (RD) was most mentioned, coded 142 times; functional (F) 102; emancipation (EM) 69; enculturation (EN) 64; and critical thinking (CT) 27. Some respondents simply evaluated the relationship (e.g. ‘my supervisors are great’ R208Footnote 3) which were coded only in terms of polarity. Many students were able to draw from experience of having more than one supervisor. More than half the comments reflected these relationships as positive (53%) but some were negative (21%) and others included a combination of these aspects (23%). The following quotes exemplify typical sentiments, and not surprisingly, many of these quotesFootnote 4 integrated more than one of the themes. To foreground the student voice, quotes are presented in their entirety, where practicable.

My relationships with my supervisors are excellent. I feel listened to, and my view is valued (RD). My supervisors keep an eye out for opportunities (e.g. seminars, conferences, and teaching) that might be appropriate to my development (EN). They are very supportive (RD). One of my current supervisors was also my honours supervisor, and I have worked (and continue to work) with her as a research assistant. This provides constant contact and opportunities for me to ask any questions related to PhD in an informal setting (EN) (R249, S1)

I was blessed to have great supervisors (RD). I believe their attitude towards me has been very important. They are always supportive (emotionally and academically), understanding (RD), and have been treating me like a peer rather than a student (EM). I believe them being accessible is very important. We meet regularly (F) (R402, S2)

These quotes highlight how positive relational experiences were fostered by reciprocal communication, attitudes and behaviours towards them as emerging researchers/academics, not merely as students. When supervisors were proactive in connecting students with opportunities to attend events or work, students were being exposed to and learning different ways of being and doing academic work that were discipline or research interest-related. Regular meetings were also mentioned as important for the performative aspect of the degree. However, the perspectives in the following responses provide insight into the effect of supervisor relationships which have been negative:

Hard work. Difficult to develop personal relationships from a distance. First primary supervisor leaving three months in highly disruptive and felt disrespectful as not given any indication it was possible when taken on (RD) (R258, S1)

Supervisors have kept me at a distance throughout this experience (RD). Even though I have struggled with the writing they have & continue to give the same advice they have given for the past four years (EM). They are also only interested in editing complete chapters which means I can waste up to 3–4 months of work & not realise it (F). This relationship has not been helpful or supportive & has turned this experience into the worse academic experience of my life (RD, EM) (R239, S4)

Many students had multiple supervision experiences and some of these were in stark contrast to each other, as articulated in these responses:

My supervisors have been very happy and supportive on both personal and professional levels, which has helped the development of those relationships (RD). I have another supervisor that consistently talks down to me, telling me that I’m not good enough to do things on my own (RD, EM) (R340, S4)

My primary supervisor was amazing at reaching out to build a relationship with me. He invited me and my partner to his house for dinner when I first arrived (RD) and organised informal meetings over coffee every week (F). He consistently invited me and other students to his house for events, to the canteen for lunch or to the pub on campus for drinks after work (EN)…My secondary supervisor, however, never got to know me…We hardly spoke outside of supervision meetings and I’m not convinced she even remembered my research topic at times (RD) (R174, S7)

Students mentioned the role of feedback and frank conversations on their work as beneficial, for example:

My supervisors have been wonderful: encouraging and hands-on, perceptive to challenges, frequently giving useful advice and honest feedback (CT) (R384, S2).

In the next excerpt the effect of non-constructive feedback is evident:

I felt that (my supervisor) was attacking me by repeatedly focusing on the things I hadn’t done, rather than giving me feedback on the things I had (CT); or commenting on the theoretical directions that worked (rather than honing in on the one that didn’t) (EM) (R206, S5)

6.2 Peer Relationships

Coding the peer relationship comments yielded a total of 394 instances showing how students perceived these relationships. In order of frequency, relationship development was coded 224 times, enculturation 98, critical thinking 17, functional 6, and emancipation 0. Some respondents simply evaluated the relationship (e.g. ‘No study peer relationships formed’ R187), coded for polarity. Interestingly, having access to a (shared) office space was mentioned by 49 respondents mostly as an enabler of peer relationships though sometimes as constraining. These were coded as ‘co-location’, a sub-theme we added to Relationship Building. Almost half reflected on peer relationships as positive (48%), around a quarter were negative (23%), while another quarter considered positive and negative aspects (25%). Many who considered these relationships in negative terms included that they were distance or part-time students, studying at home or elsewhere, working off-campus full/part-time, lacking time due to family or other commitments. A few stated they were not inclined to invest in peer relationships.

Similar to the findings in the previous section, students often described their experiences with peers in complex ways necessitating multiple coding. The following are some typical insights:

I have met a wonderful and supportive group of students via my principal supervisor. We are spread out around Australia, however [we meet] via zoom monthly and we get to connect and share our research (RD, EN). I’ve connected on LinkedIn and twitter and regularly engage in sharing ideas, debates and literature (CT). We have also met up at a conference, which was great to have some deep conversations (RD, EN) (R171, S1)

My closest study peer is a PhD student from another university…we will often provide emotional support and de-briefs. We know each other’s projects quite well and will bounce ideas, share resources, write together and read each other’s work (EN). If I did not have this peer I would have struggled and felt far more isolated than I have (RD) (R119, S2)

Very close. We met weekly as part of an organized doctoral seminar to give feedback on each other’s drafts and ideas (RD, CT). That sense of community has been crucial for all of us I think (EN) (R122, S7)

These students express peer relationships as enhancing the research experience and beyond. Activities organised by peers for peers also contributed to a sense of belonging through the opportunities that arose for sharing emotionally, socially and academically. However, where peer relationships were under-developed or dysfunctional, the experience was often reflected on negatively. The following provide insight into some mixed experiences in developing peer relations:

Because I’ve largely been working from home I have not had as much contact with my peers as I would have liked (RD, CoL). The lack of designated desk space for part-time PhD candidates is a problem (CoL)…The most consistent relationships are those with other PhD candidates that are also casual tutors in (professional) Unit - we support each other and try to have lunch at least once over a semester, as well as coffee/lunch (RD) (R324, S3)

Fairly close at the beginning because we shared a common office (RD, CoL). Changes to the location of offices disrupted these relationships (RD, CoL) (R50, S3)

Having a large group of peers working in the one room has enabled lifelong relationships to develop (RD, CoL). It has also led to disagreements with people with strong and opposing personalities (RD, CoL) (R346, S2)

A few students spoke of the impact of toxic personalities:

Good with some, I have made a few office friends. But some have been quite competitive, gossiping, and negative. Others are very disengaged. The culture is terrible (RD, EN) (R105, S5)

What has hindered is some toxic personalities that makes me anxious about forming connections with others (RD) (R31, S1)

7 Discussion and Conclusions

These findings highlight that the quality of social interaction has significant impact on identity and notions of belonging, with implications for how support through more holistic initiatives may better equip graduates for success during their research degrees and beyond. While each of the themes are intertwined, discussion follows the five themes, together with leitmotifs from Dr. Seuss’ Oh, the places you’ll go! which align playfully with aspects of the student experience.

7.1 Functional

You have brains in your head, you have feet in your shoes, you can steer yourself in any direction you choose

Supervisors were key to the functional aspects of student experience, particularly for keeping on-track as myriad distractions and side-tracks can arise. Developing healthy supervisory relationships helped students with the process of achieving milestones (Fillery-Travis & Robinson, 2018). In particular, regular meetings were deemed valuable, if these established ‘shared values, respect for each other and agreeing on expectations’ (Lee, 2018, p. 884). Positive peer interactions were also appreciated and added to increasing performativity and milestone achievement. In these relationships, students found positive functional interactions affected all aspects of their study experience.

7.2 Enculturation

You’ll be on your way up! You’ll be seeing great sights! You’ll join the high fliers who soar to high heights.

Becoming part of academic culture is important for these students who frequently work in isolation. Opportunities to feel a sense of belonging—joining ‘the high fliers’—provide examples and implicit understandings of the norms and practices of the community. Relationships with supervisors and peers were essential for creating spaces and reasons to interact which enhanced student experiences. These included, but were not limited to, casual coffee catchups, meals shared, seminars, part-time research assistant work or teaching engagements.

Networking opportunities provided by the institution, faculty or supervisor were key to ‘helping [students] feel part of the academic community and engaged in the ongoing identity development process’ (Baker & Pifer, 2011, p. 9). Flores-Scott and Nerad (2012) acknowledge the role of peers as ‘important agents of community, learning, and development’ (p. 75). Indeed, development of skills around networking and collaborating contributes to academic identity and confidence, producing greater independence.

7.3 Critical Thinking

And if you go in, should you turn left or right … or right-and-three-quarters? Or maybe, not quite? Or go around the back and sneak in from behind? Simple it’s not, I’m afraid you will find for a mind-maker-upper to make up his mind

The development of academic skills, particularly critical thinking demanded by both the Academy and industry employers, is increasingly impacting the structure of postgraduate research degrees (Jones, 2018). The nature of the feedback provided to students, the opportunities to engage with modelled critical approaches and behaviours, and the openings they are enabled to take up within the Academy all influence student outcomes. This was also significant in the peer relationships students formed which further impacted identity formation (Flores-Scott & Nerad, 2012).

7.4 Emancipation

The waiting place … that’s not for you! Somehow, you’ll escape all that waiting and staying. You’ll find the bright places where Boom Bands are playing. With banners flip-flapping once more you’ll ride high! Ready for anything under the sky.

Student expectations included supervisory practices that ideally aided resilience in the ebb-and-flow of shifting student identities: from knowledgeable outsider to student, toward becoming an independent scholar destined for employment post-graduation. As noted by Rogers-Shaw & Carr-Chellman, when students ‘acknowledged feeling respected and recognized by peers and professors in their programs’ (2018, p. 246) a greater awareness of their own capabilities resulted. Venturing into the unknown is also a shared responsibility, influenced by ‘the identity the learner wishes to maintain’ and learning in ways that ‘challenge the status quo’ (Boud et al., 2018, p. 917). However, where relationships highlighted micro-managing or a perceived lack of respect this led students to doubt their abilities and distrust their supervisors.

7.5 Relationship Development

And when you’re alone there’s a very good chance you’ll meet things that will scare you right out of your pants. There are some, down the road between hither and yon, that can scare you so much you won’t want to go on. But on you will go …

The research degree experience is often likened to an amusement park ride: ‘it’s like a rollercoaster. Some days are going to be awesome and others are going to be hell. But it’s part of the growth process you go through as an academic’ (R305, L2&3). During this ‘rollercoaster’ ride, the goodwill, friendship and wisdom developed in relationships with supervisors and peers was consistently acknowledged as important to persisting and identity formation. Where positive relationships were developed and sustained, students outlined a greater sense of belonging in the community as well as greater levels of confidence in successful participation. Fillery-Travis and Robinson (2018) emphasize the importance of quality in interpersonal factors which develop ‘trust, respect, liking, support, responsiveness, cooperation and openness’ (p. 851), contributing to the quality of the student-supervisor relationship. Students also noted that social and intellectual support from supervisors and peers, not only built community but also assisted proactive involvement (Lee, 2018). The converse was also true, where students experienced poor relationships with supervisors or peers, they experienced lower confidence in the academic community, increased frustrations and greater antagonism during the study process.

8 Conclusion

Clarity around the significant impact of supervisory and peer relationships on the postgraduate student experience was enabled through Lee’s framework (2018). With 425 students contributing to this survey from 15 countries, across all discipline areas, their many voices came together as one. These relationships affected not only their experiences of study from day-to-day, but also their feelings of confidence within the study processes and their determination for future success following their student experience. The leitmotif of Dr. Seuss’ children’s book harkens to a journey of difficulty, isolation, successes, adventure, hardships and character-building, finishing with this single line…perhaps most relevant to every research student’s dream:

And will you succeed? Yes! You will, indeed! (98 and ¾ percent guaranteed)

KID YOU’LL MOVE MOUNTAINS!

Notes

- 1.

We use the term ‘postgraduate research student’ to describe a student engaged in a range of programs termed variously, including Ph.D., professional doctoral programs (see Jones, 2018, p. 817), also Masters of Philosophy (M.Phil) or Masters by Research. For brevity, hereafter we refer to them as ‘student(s)’.

- 2.

This total takes into account 5 incomplete surveys which were removed.

- 3.

‘R’ = respondent identification.

- 4.

Note: student quotes are followed by respondent number and stage of degree (1–7, see Table 18.1), presented thus: (R233, S2).

References

Andrews, M., Squire, C., & Tamboukou, M. (Eds.). (2008). Doing narrative research. London: Sage.

Australia, Universities. (2015). Higher education and research: Facts and figures. Sydney: Universities Australia.

Baker, V. L., & Pifer, M. J. (2011). The role of relationships in the transition from doctoral student to independent scholar. Studies in Continuing Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2010.515569.

Becker, S. A., Brown, M., Dahlstrom, E., Davis, A., DePaul, K., Diaz, V., et al. (2018). NMC horizon report 2018 higher (Education ed.). Louisville: CO. EDUCAUSE.

Boud, D., Fillery-Travis, A., Pizzolato, N., & Sutton, B. (2018). The influence of professional doctorates on practice and the workplace. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1438121.

Crotty, M. (1998). The foundations of social research: Meaning and perspective in the research process. St Leonards, NSW: Allen and Unwin.

Dr. Seuss. (1957). Oh, the places you’ll go!. London: Harper Collins Children’s Books.

Fillery-Travis, A., & Robinson, L. (2018). Studies in higher education making the familiar strange-a research pedagogy for practice making the familiar strange-a research pedagogy for practice. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1438098org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1438098.

Flores-Scott, E. M., & Nerad, M. (2012). Peers in doctoral education: Unrecognized learning partners. New Directions for Higher Education, 2012, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.v2012.157.

Gee, J. P. (2000). Identity as an analytic lens for research in education. Review of Research in Education, 25(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X025001099.

Harden-Thew, K. (2014). Story, restory, negotiation: Emergent bilingual children making the transition to school. Thesis: University of Wollongong. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12421.55529.

Jones, M. (2018). Contemporary trends in professional doctorates. Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1438095.

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2012). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Abingdon UK: Routledge.

Lansoght, E. (n.d) PhDtalk blogspot. Accessed http://phdtalk.blogspot.com.au/2012/06/ten-great-blogs-for-phd-students.html.

Lee, A. (2018). How can we develop supervisors for the modern doctorate? Studies in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1438116.

Lundsteen, N. (2014). Doctoral Career paths and ‘Learning to be. In S. Carter & D. Laurs (Eds.), Generic support for doctoral students: Practice and pedagogy. New York: Routledge.

Marsh, H., &Western, M. (2016) How to improve research training in Australia— give industry placements to Ph.D. students. The Conversation, 19 April, 2016. https://theconversation.com/how-to-improve-research-training-in-australia-give-industry-placements-to-phd-students-57972.

Mewburn, I (n.d.) The thesis whisperer blog. Accessed from https://thesiswhisperer.com/.

Norton, A., & Cherastidtham, I., (2014). Mapping Australian higher education, 2014–15, Grattan Institute.

Rogers-Shaw, C., & Carr-Chellman, D. (2018). Developing care and socio-emotional learning in first year doctoral students: Building capacity for success, 13. https://doi.org/10.28945/4064.

Spyrou, S. (2011). The limits of children’s voices: From authenticity to critical, reflexive representation. Childhood, 18, 151–165.

Stone, C., & O’Shea, S. (2012). Transformations and self discovery. Champaign, Illinois: Common Ground Publishing.

Whannell, R., & Whannell, P. (2015). Identity theory as a theoretical framework to understand attrition for university students in transition. Student Success, 6(2), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.v6i2.286.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Delahunty, J., Harden-Thew, K. (2019). ‘Oh, The Places You’ll Go’: The Importance of Relationships on Postgraduate Research Students’ Experiences of Academia. In: Diver, A. (eds) Employability via Higher Education: Sustainability as Scholarship. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26342-3_18

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26342-3_18

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-26341-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-26342-3

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)