Abstract

The quality of data determines the ability to make a decision in the era of evidence-based medicine. A discussion around the level of evidence provided by an individual study is helpful in this process. Laparoscopic treatment of colorectal disease has been subjected to all levels of scrutiny from Levels 1 to 4, and there is enough data in the recent decade alone to determine that laparoscopic approaches to colorectal disease should be considered standard of care.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction and Rationale

The original concept of laparoscopic colectomy was to minimize the surface impact on the abdominal wall, while the same extent of resection was being performed on the colon, as might be accomplished through an open large incision. Since that concept was proposed and started in 1991 with the first case report of a laparoscopic right colectomy , the ability of laparoscopic surgeons has increased to the point that almost all operations on the entire gastrointestinal tract can be accomplished laparoscopically. It is remarkable that laparoscopic technique and instrumentation have not changed much from the initial explosion of long straight instruments inserted through the abdominal wall access ports which mirrored most of the instruments used in open operations. Laparoscopy is considered standard of care for most general surgical procedures, and the same can be said for colorectal operations, even though some surgeons lag behind in adoption of the approach. The evidence is mature and fills the surgical literature with solid evidence that laparoscopic techniques can be utilized for almost all routine and even some advanced colorectal procedures .

Levels of Evidence and Data Quality

As we consider recent publications on outcomes from laparoscopic operations, we should only accept Level 1 or 2 evidence to make our decisions and adhere to the principles of evidence-based practice . The early reports of laparoscopic techniques and outcomes were in the form of case reports or small, single-institution, retrospective reviews of consecutive patient series with, at best, a case-matched retrospective historical control group of patients treated with open technique. This barely qualified as Level 4 evidence on the literature quality scale, where randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are considered Level 2 and systematic meta-analysis of data from similar-design, RCTs is considered Level 1 evidence (e.g., Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews) [1, 2]. In the early days of laparoscopic general surgery, very few randomized controlled trials for comparison of outcomes between minimally invasive and open procedures were performed. Fortunately, comparison of large retrospective series with historic outcomes measures was able to detect a rise in complication rates (e.g., bile duct injury during cholecystectomy). Efforts were redirected to make the minimally invasive approach as safe as the open approach while maintaining the benefits of minimally invasive access to abdominal organs (e.g., development of the critical view of the portal structures and cystic duct in cholecystectomy). Meta-analysis of these retrospective series reviews, without case matching or propensity score-controlled adjustment, does not improve the quality of the data because the biases of selection and partial follow-up persist. Combining data simply increases the number of subjects to make a comparison statistically significant.

Fortunately, colorectal surgeons have learned that RCTs will answer specific questions without controversy in most circumstances. The area of laparoscopic resection for colorectal cancer has been the most studied [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. The complexity of designing an RCT is based on selecting a homogeneous population with as few confounding factors as possible and applying a consistent approach to the disease and patient to achieve predetermined primary and secondary outcomes. Randomization can remove almost all selection bias from the process, and prospectively collected data are usually more complete and less likely to be manipulated. Colon and rectal cancers have been the focus of most RCTs in colorectal surgery and continue to populate the literature. As mentioned above, the meta-analysis of the combined data from RCTs can provide the clearest answer to a major question like cancer treatment. It is important to try to standardize the confounding factors in each trial to make the combined analysis meaningful. For example, the definition of the rectum or the segments of the colon used in the study will make a difference in the ability to draw a conclusion. Dr. Lars Pahlmann took the data from the early RCTs studying laparoscopic colectomy for cancer to provide a meta-analysis of combined trials and confirmed equivalence of laparoscopic and open approaches to colon cancer [14]. It is hoped that combined data analysis of the recently published rectal cancer trials will give us the same confidence in the use of laparoscopy in patients with rectal cancer.

Reviews of large administrative databases (e.g., National Inpatient Sample [15] and Premier Prospective Database [16] and California Cross Section Database [17]) provide adequate numbers of patients to result in statistical significance for even small differences in outcomes across a wide spectrum of patients, hospitals, and surgeons. It is important to remember that these large databases are usually reservoirs of data from hospitals and insurance companies that utilize relatively untrained personnel to enter the data at the patient interface. The data are collected with limited filters, other than the fact that the patient had a procedure or a disease process based on codes. Some databases are able to include severity of illness information and enhance comparison of patients based on comorbidities and other individual features of the patient. The integration of disease codes , procedure codes, and billing codes can sometimes be faulty and give a false sense of security and accuracy based on large numbers alone.

The best technique for managing retrospective data is achieved by educated, specifically trained, data abstractors and entry personnel focused on a set of definitions, rules, and criteria for specific conditions and outcomes. The National Surgical Quality Improvement Project (NSQIP) [18], the Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) database , and the National Cancer Database (NCDB) at the American College of Surgeons are examples of trustworthy databases that can give a reliable answer even within the limitations of retrospective data. The quality of the data needs to be considered when evaluating outcomes of different techniques. Each database has its own limitations based on the comprehensiveness of the data collected, which is constrained by time, resources, and storage capacity. Fortunately, the newest data collection effort in colorectal surgery is supported by the NCDB with prospective rectal cancer-specific data collection through the National Accreditation Program in Rectal Cancer (NAPRC) managed by the American College of Surgeons. These data elements were collaboratively defined by consensus within the multidisciplinary OSTRiCh (Optimizing Surgical Treatment of Rectal Cancer) Consortium during the design phase of the NAPRC. As the NAPRC functions, data points will be changed to answer new questions relevant to clinical practice.

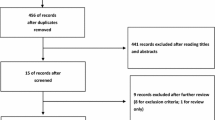

If laparoscopic colorectal surgery is to be considered as standard of care over open surgery, we need contemporary data and reports from the literature to confirm ongoing safety and quality of outcomes from the laparoscopic approach. A search of the surgical literature back to 2006 yielded a large number of reports (134) comparing open and laparoscopic colorectal surgery. A selection process that focused on resection of the colon and rectum and comparison of the 2 approaches yielded 25 articles that deserve discussion. Comparison of different aspects of the procedure and a range of outcomes have been reported in the past decade in large database reviews, systematic meta-analysis, randomized controlled trials, and prospective non-randomized series. The bottom line reflects the ability of laparoscopic colorectal surgery to achieve excellent outcomes and improve on some of the aspects of recovery over the open approach.

Outcomes

The benefit of laparoscopy is most realized in the short-term outcomes of length of stay and postoperative pain . These are uniformly superior to the open technique. Mortality after a laparoscopic colorectal procedure has been reported to be less than after an open resection (0.52% vs 1.24%) (relative risk = 0.69) (0.4% vs 2.0%) [15, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Length of stay is always shorter by multiple days for laparoscopic resections compared to open [6, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Complications over a broad spectrum of definitions are always fewer for laparoscopic procedures [16, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Laparoscopy acts in conjunction with protocols for enhanced recovery after surgery to improve outcomes after colectomy [6, 23].

The cost of laparoscopic procedures to the system, while higher in the operating room, has been shown to be lower overall, due to reduced complications and length of stay [15, 16]. Cost comparisons warrant further investigation as the application of technologic advances including robotic-assisted surgery increases in colorectal surgery. Cancer outcomes after laparoscopic surgery have been shown to be the same as for open operation including survival, recurrence, lymph node harvest, and ability to resect locally advanced, emergently operated, obstructed tumors from all sections of the colon and the rectum and in elderly and high-risk patients [4,5,6, 15, 20, 22, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Several rectal cancer trials have developed the concept of the composite pathologic assessment as an immediate oncologic outcome. Long-term outcomes of 3- or 5-year overall survival, disease-free survival, and local recurrence are considered non-inferior and therefore acceptable as a preferred standard owing to its short-term benefits.

Hand-assisted laparoscopic techniques have been shown to provide equivalent outcomes to open and straight laparoscopic colorectal resections with a lower conversion rate and shortened learning curve [19, 31, 32]. Sexual and bladder function may be impacted by laparoscopic techniques used in low rectal resection; otherwise, quality of life is similar to open results [3, 5]. Conversion from laparoscopic to open operation has been shown to impact outcomes adversely [3, 32, 33]. Conversion is associated with longer length of stay, higher rates of readmission, and higher rates of postoperative complications. Studies have reported negative oncologic outcomes following conversion; however, when adjusting for other factors, perioperative outcomes and pathologic features are more predictive of oncologic endpoints such that conversion may be a proxy for more biologically aggressive disease or a more susceptible patient [34].

Laparoscopy for the management of benign disease including inflammatory bowel disease and diverticulitis is well studied and is extensively covered in several subsequent chapters. In the two available randomized controlled trials that consider laparoscopic over open ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease, despite a longer operative time with laparoscopy, laparoscopy was found to be feasible, safe, and with low conversion rate provided procedures were performed with proper patient selection and by experienced surgeons. There is strong evidence that laparoscopic sigmoid resection offers the benefit of reduction in major complications and shorter hospital stay over open resection [35,36,37]. There are no randomized data for laparoscopic treatment of small intestinal obstruction [2].

See Table 6.1.

Conclusion

In summary, there is high-quality evidence the supports laparoscopic treatment of most colorectal diseases. Outcomes are generally equivalent if not better than open operation in almost all parameters. Laparoscopy for both benign and malignant colorectal diseases should be considered whenever possible, and surgeons should now consider laparoscopy as standard of care. As technological advances in the field of minimally invasive surgery continue to evolve, surgeons must continue to validate the safety and feasibility of these newer technologies with high-quality evidence.

References

Dasari BV, McKay D, Gardiner K. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for small bowel Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;19(1):CD006956.

Cirocchi R, Abraha I, Farinella E, Montedori A, Sciannameo F. Laparoscopic versus open surgery in small bowel obstruction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;17(2):CD007511.

Jayne DG, Brown JM, Thorpe H, Walker J, Quirke P, Guillou PJ. Bladder and sexual function following resection for rectal cancer in a randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open technique. Br J Surg. 2005;92(9):1124–32.

Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH, Kim S, Kang SB, Lim SB, et al. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(7):767–74.

McCombie AM, Frizelle F, Bagshaw PF, Frampton CM, Hewett PJ, McMurrick PJ, et al. The ALCCaS trial: a randomized controlled trial comparing quality of life following laparoscopic versus open colectomy for colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(10):1156–62.

King PM, Blazeby JM, Ewings FPJ, Longman RJ, Kendrick AH, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery for colorectal cancer within an enhanced recovery programme. Br J Surg. 2006;93(3):300–8.

Fleshman J, Sargent DJ, Green E, Anvari M, Stryker SJ, Beart RW Jr, et al. Laparoscopic colectomy for cancer is not inferior to open surgery based on 5-year data from the COST Study Group trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246(4):655–62; discussion 662–664

Fleshman J, Branda M, Sargent DJ, Boller AM, George V, Abbas M, et al. Effect of laparoscopic-assisted resection vs open resection of stage II or III rectal cancer on pathologic outcomes: the ACOSOG Z6051 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1346–55.

Fleshman J, Branda ME, Sargent DJ, Boller AM, George VV, Abbas MA, et al. Disease-free survival and local recurrence for laparoscopic resection compared to open resection of stage II to III rectal cancer: follow-up results of the ACOSOG Z6051 randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2019;269(4):589–95.

Stevenson AR, Solomon MJ, Lumley JW, Hewett P, Clouston AD, Gebski VJ, et al. Effect of laparoscopic-assisted resection vs open resection on pathological outcomes in rectal cancer: the ALACaRT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1356–63.

Stevenson ARL, Solomon MJ, Brown CSB, Lumley JW, Hewett P, Clouston AD, et al. Disease-free survival and local recurrence after laparoscopic-assisted resection or open resection for rectal cancer: the Australasian Laparoscopic Cancer of the Rectum Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Surg. 2019;269(4):596–602.

COLOR Study Group. COLOR: a rancomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open resection for colon cancer. Dig Surg. 2000;17(6):617–22.

COLOR II Study Group, Buunen M, Bonjer HJ, Hop WC, Haglind E, Kurlberg G, et al. COLOR II. A randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery for rectal cancer. Dan Med Bull. 2009;56(2):89–91.

Bonjer HJ, Brown J, Delgado S, Kuhrij E, Haglind E, Pahlmann L. Laparoscopically assisted vs open colectomy for colon cancer: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2007;142(3):298–303.

Lee MTG, Chiu CC, Wang CC, Chang CN, Lee SH, Lee M, et al. Trends and outcomes of surgical treatment for colorectal cancer between 2004 and 2012 – an analysis using national inpatient database. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):2006.

Keller DS, Delaney CP, Hashemi HEM. A national evaluation of clinical and economic outcomes in open versus laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(10):4220–8.

Patel SS, Patel MS, Mahanti S, Ortega A, Ault GT, Kaiser AM, et al. Laparoscopic versus open colon resections in California: a cross-sectional analysis. Am Surg. 2012;78(10):1063–5.

Ballian N, Weisensel N, Rajamanickam V, Foley EF, Heise CP, Harms BA, et al. Comparable postoperative morbidity and mortality after laparoscopic and open emergent restorative colectomy: outcomes from the ACS NSQIP. World J Surg. 2012;36(10):2488–96.

Zhang X, Wu Q, Gu C, Hu T, Bi L, Wang Z. Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery versus conventional open surgery in intraoperative and postoperative outcomes for colorectal cancer. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96:33(e7794).

Cirocchi R, Campanile FC, Di Saverio S, Popivanov G, Carlini L, Pironi D, et al. Laparoscopic versus open colectomy for obstructing right colon cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Visc Surg. 2017;154:387–99.

Malczak P, Mizera M, Torbica G, Witowski J, Major P, Pisarska M, et al. Is the laparoscopic approach for rectal cancer superior to open surgery? A systematic review and meta-analysis on short-term surgical outcomes. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyine. 2018;13(2):129–40.

Nagasue Y, Akiyoshi T, Ueno M, Fukunaga Y, Nagayama S, Fujimoto Y, et al. Laparoscopic versus open multivisceral resection for primary colorectal cancer: comparison of perioperative outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(7):1299–305.

Zhuang CL, Huang DD, Chen FF, Zhou CJ, Zheng BS, Chen BC, et al. Laparoscopic versus open colorectal surgery within enhanced recovery after surgery programs: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2015;9(8):2091–100.

Yamaguchi S, Tashiro J, Araki R, Okuda J, Hanai T, Otsuka K, et al. Laparoscopic versus open resection for transverse and descending colon cancer: short-term and long-term outcomes of a multicenter retrospective study of 1830 patients. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2017;10(3):268–75.

Yamamoto S, Hinoi T, Niitsu H, Okajima M, Ide Y, Murata K, et al. Influence of previous abdominal surgery on surgical outcomes between laparoscopic and open surgery in elderly patients with colorectal cancer: subanalysis of a large multicenter study in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(6):695–704.

Zeng WG, Zhou ZX, Hou HR, Liang JW, Zhou HT, Wang Z, et al. Outcome of laparoscopic versus open resection for rectal cancer in elderly patients. J Surg Res. 2015;193(2):613–8.

Hida K, Hasegawa S, Kinjo Y, Yoshimura K, Inomata M, Ito M, et al. Open versus laparoscopic resection of primary tumor for incurable stage IV colorectal cancer: a large multicenter consecutive patients cohort study. Ann Surg. 2012;255(5):929–34.

Hemandas AK, Abdelrahman T, Flashman KG, Skull AJ, Senapati A, O’Leary DP, et al. Laparoscopic colorectal surgery produces better outcomes for high risk cancer patients compared to open surgery. Ann Surg. 2010;252(1):84–9.

Athanasiou CD, Robinson J, Yiasemidou M, Lockwood S, Markides GA. Laparoscopic vs open approach for transverse colon cancer. A systematic review and meta-analysis of short and long term outcomes. Int J Surg. 2017;41:78–85.

Han SA, Lee WY, Park CM, Yun SH, Chun HK. Comparison of immunologic outcomes of laparoscopic vs open approaches in clinical stage III colorectal cancer. Int J Color Dis. 2010;25(5):631–8.

Duraes L, Schroeder DA, Dietz DW. Modified pfannenstiel open approach as an alternative to laparoscopic total proctocolectomy and IPAA: comparison of short- and long-term outcomes and quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(5):573–8.

Ozturk E, Kiran RP, Remzi F, Geisler D, Fazio V. Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery may be a useful tool for surgeons early in the learning curve performing total abdominal colectomy. Color Dis. 2010;12(3):199–205.

Masoomi H, Moghadamyeghaneh A, Mills S, Carmichael JC, Pigazzi A, Stamos MJ. Risk factors for conversion of laparoscopic colorectal surgery to open surgery: does conversion worsen outcome? World J Surg. 2015;39(5):1240–7.

Leijssen LGJ, Dinaux AM, Kunitake H, Bordeianou LG, Berger DL. Is there a drawback of converting a laparoscopic colectomy in Colon Cancer? J Surg Res. 2018;232:595–604.

Milsom JW, Hammerhofer KA, Böhm B, Marcello P, Elson P, Fazio VW. Prospective, randomized trial comparing laparoscopic vs. conventional surgery for refractory ileocolic Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon and Rectum. 2001;44(1):1–8. Discussion 8–9

Gervaz P, Inan I, Perneger T, Schiffer E, Morel P. A prospective, randomized, single-blind comparison of laparoscopic versus open sigmoid colectomy for diverticulitis. Ann Surg. 2010;252(1):3–8.

Klarenbeek BR, Veenhof AA, Bergamaschi R, van der Peet DL, van den Broek WT, de Lange ES. Laparoscopic sigmoid resection for diverticulitis decreases major morbidity rates: a randomized control trial. Ann Surg. 2009;249(1):39–44.

Veldkamp R, Kuhry E, Hop WC, Jeekel J, Kazemier G, Bonjer HJ, et al. Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(7):477–84.

Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, et al. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1718–26.

Green BL, Marshall HC, Collinson F, Quirke P, Guillou P, Jayne DG, et al. Long-term follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of conventional versus laparoscopically assisted resection in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100(1):75–82.

Maartense S, Dunker MS, Slors JF, Cuesta MA, Pierik EG, Gouma DJ, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2006;243(2):143–9; discussion 150–3

Stocchi L, Milsom JW, Fazio VW. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic versus open ileocolic resection for Crohn’s disease: follow-up of a prospective randomized trial. Surgery. 2008;144(4):622–7; discussion 627–8

Gervaz P, Mugnier-Konrad B, Morel P, Huber O, Inan I. Laparoscopic versus open sigmoid resection for diverticulitis: long-term results of a prospective, randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(10):3373–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Wells, K., Fleshman, J. (2020). Laparoscopy Versus Open Colorectal Surgery: How Strong Is the Evidence?. In: Sylla, P., Kaiser, A., Popowich, D. (eds) The SAGES Manual of Colorectal Surgery. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24812-3_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24812-3_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-24811-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-24812-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)