Abstract

Just after the turn of the century, when the “leading edge” of the baby boomers approached the age of 65, there was an increase in the public attention devoted to the work and retirement intentions of older adults. Some experts voiced worries about the economic fragility of older Americans who might struggle to support their households with the conventional “three-legged stool” set of strategies (i.e., savings/investments, Social Security, and private pensions). In response, researchers began to take a serious look at the options and benefits associated with voluntary extension of the labor force participation of older adults. While the arguments for working longer are multi-faceted, there is wide recognition that older adults who are able to work past the normative retirement age (62–65 years) can benefit from the financial benefits offered by employment (both income and possible access to continued employer-sponsored benefits). In this chapter, we present an argument with supporting evidence that job quality affects older adults’ intentions with regard to their transitions into retirement. We found that, compared to employees who report that they intend to stay with their current employer “until they retire,” there are negative relationships between satisfaction with meaningful work as well as with compensation and the intent to leave before they retire (in the next 5 years).

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Intent to retire

- Quality of employment

- Factors predicting retirement

- Aspects of work experience

- Employees’ reported well-being

- Temporal self-appraisal theory

1 Introduction

Just after the turn of the century, when the “leading edge” of the baby boomers approached the age of 65, there was an increase in the public attention devoted to the work and retirement intentions of older adults. In part, this focal shift reflected concerns about the unprecedented numbers of older adults who were about to become eligible for public supports including Medicare and Social Security. In addition, some experts voiced worries about the economic fragility of older Americans who might struggle to support their households with the conventional “three-legged stool” set of strategies: savings/investments, Social Security, and private pensions. And, employers in some industry sectors expressed anxiety about possible labor market shortages if large numbers of older adults retired and if there were not sufficient numbers of qualified “replacement” employees (that is, early career workforce entrants) in sight. In response, researchers such as Munnell and Sass (2008) began to take a serious look at the options and benefits associated with voluntary extension of the labor force participation among older adults (see also OECD, 2018). While the arguments for working longer are multi-faceted, there was growing recognition that older adults who were able and wanted to work past the normative retirement age (62–65 years) could benefit from the financial rewards offered by employment (both income and possible access to continued employer-sponsored benefits).

Some scholars and advocates have raised words of caution about new norms for the extension of the work lives of older adults. They point out that: (a) some older adults (including those who have worked in jobs that were physically demanding) might not be able to continue to work in their career occupations; (b) the declining health of some older adults can make it difficult for them to continue to work; (c) older adults who left the workforce early (whether as a result of voluntary early retirement or involuntary unemployment) often find it extremely difficult to change course and re-enter the workforce, in part due to age discrimination; and (d) the structure of many jobs and work environments do not seem to align well with the needs, priorities, and preferences of many older adults. This latter point stresses that while it might be possible for older adults to retain or find “some” job, the jobs that older adults are able to secure might not reflect the type of work arrangement that promotes their social, emotional, and physical health—in addition to their financial health. In this chapter, we present an argument with supporting evidence that job quality affects older adults’ intentions with regard to the transitions to retirement.

2 Literature Review

In this section of the chapter, we first consider ways that older adults might anticipate their “future selves,” using some of the key tenets of temporal self-appraisal theory. Survey data about employees’ expectations and behaviors with regard to the timing of their retirement are presented. We then consider the findings of research that has identified factors associated with the timing of retirement. At the end of this section, we summarize selected frameworks related to the construct of quality employment.

2.1 Our Future Selves

The concept of “intent to retire” focuses on ways that employees (particularly older adults) envision their “future selves” with regard to work. Temporal self-appraisal theory (e.g., Ross & Wilson, 2002) focuses attention on the ways that individuals place their self-assessments in the context of time, typically in ways that support positive self-appraisals in the present. Strahan and Wilson (2006) stress that the time context used for self-appraisal can include both “past selves” and “future selves.”

As noted by Peetz and Wilson (2008), the comparisons (and the appraisals) of “present selves” and “future selves” can be associated with goal-oriented behaviors. Hershfield (2011) discusses how perspectives of “future selves” are helpful to understand behaviors such as savings for retirement and possibly other decisions related to retirement transitions. This perspective of temporal self-appraisal theory establishes a possible connection between older adults’ experiences today (including both work and non-work experiences ), their expectations about ways that the possible continuation of their worker role might affect their self-appraisals, and plans they are making for retirement decisions that will take place in the future (either in the proximal or distant future).

In 2016, the Gallup organization polled US workers about their expectations for the timing of their future retirements (Saad, 2016). The survey found that the average age of expected retirement was 66, with 23% expecting to retire before 62; 38% between 62 and 67; and 31% after 68; and with 8% unsure. In 1995, the average expected age of retirement was just 60 years (Saad, 2016).

Despite the anticipated associations between perceptions of our “future selves” and behaviors, studies have found that there is often a gap between the anticipated age of retirement and actual age of retirement, possibly reflecting life events that occur and resultant decision-making adjustments. The Employment Benefit Research Institute (Greenwald, Copeland, & VanDerhei, 2017) found that employees are “… more likely to say they expect to retire at age 70 or older… [than who actually do retire at 70 or older]. Nearly 4 in 10 (38%) of workers expect to retire at 70 or beyond, while only 4% of retirees report this was the case.” The authors conclude that:

This difference between workers’ expected retirement age and retirees’ actual age of retirement suggests that a considerable gap exists between workers’ expectations and retirees’ experience. One reason for the gap between workers’ expectations and retirees’ experience is that many Americans find themselves retiring unexpectedly. (Greenwald et al., 2017, pp. 19–20)

2.2 Predictors of Retirement-Related Decisions

As suggested by perspectives of human and social ecology, we would expect that factors at the individual, family, organizational, and societal levels would affect the timing of retirement. Factors at all of these levels can either encourage or “force” people to sustain their current work-life patterns or they can encourage (or “force”) people to make changes (either at home or at work), possibly including a transition into retirement (see Beehr, Glazer, Nielson, & Farmer, 2000). For the purposes of this chapter, we highlight five sets of factors that have been linked with retirement decisions.

Health Status

A number of studies conducted in countries around the world have linked health declines with early retirement (e.g., Solem et al., 2016). Research with older adults in Denmark found a significant relationship between receiving a diagnosis of a medical condition and the timing of retirement (Gupta & Larsen, 2010). Olesen, Butterworth, and Rodgers (2012) found that poor physical health and poor mental health are associated with early retirement. One cross-national study found that the association between poor health and early retirement is stronger in the USA than in Australia (Sargent-Cox, Anstey, Kendig, & Skladzien, 2012).

Earnings, Household Income, and Wealth

As anticipated, studies have found relationships between wealth and retirement as well as employees’ access to health insurance and the timing of retirement (see Rogowski & Karoly, 2000). In the absence of employer-sponsored health insurance that extends into retirement, the threshold for Medicare eligibility tends to discourage voluntary retirement prior to that age. Congdon-Hohman (2015) reports that employees planning for retirement may also factor in their spouses’ eligibility for Medicare. Mermin, Johnson, and Murphy (2007) indicate that lack of access to employer-sponsored retiree health benefits is one factor that can increase the likelihood of extending labor force attachment.

Employment Status of Spouse

While there is some evidence that partners, husbands, and wives might make at least some of their retirement-related decisions as couples, a coordinated timing of retirement may be complicated for dual-earner couples if they are eligible for their public or private pensions at different times (for example, if there is an age difference between the two earners; see Johnson, 2004; O’Rand & Farkas, 2002).

Family Responsibilities and Personal Interests

Although the nature of family responsibilities typically changes over the life course, the interactions of work and family roles have been well documented. Older adults might find that responsibilities associated with caring for grandchildren, adult children (for example, those who have disabilities or those who need financial assistance from their parents), spouses, and elderly parents have an impact on retirement decisions (see discussion in De Preter, Van Looy, Mortelmans, & Denaeghel, 2013). Lumsdaine and Vermeer (2015) report that the birth of a new grandchild increases the likelihood of retirement (although they do not report relationships between responsibilities for caregiving to those grandchildren and retirement behaviors). Szinovacz, DeViney, and Davey (2001) examine the impact of family relationships and report that intergenerational financial transfers (that is, financial contributions to children) as well as having children residing in the household were associated with lower likelihoods of retirement. Lilly, LaPorte, and Coyte (2007) report that older employees with significant eldercare responsibilities are likely to withdraw from the labor force compared to their colleagues.

Economic Trends and Industry Norms

Research findings are mixed with the extent to which older adults may think about their “future selves” in the context of the “future economy.” Some scholars have examined whether people who anticipate turbulent economic times ahead might become more risk aversive and, therefore, report that they intend to work longer than they might otherwise have done (see Dudel & Mikko, 2017). However, Coile and Levine’s historical analysis (2006) did not find evidence of this relationship, in part due to the small percentage of older adults having significant stock investments. While the effect of the macro economy might seem relatively small (see Gustman, Steinmeier, & Tabataba, 2012), McFall (2011) found relationships among wealth loss from 2008 to 2009 (the “Great Recession”), optimism or pessimism about future economic trends and anticipated dates of retirement, with an average increase of 2.5 months in older adults (at least 40 years of age) expected retirement dates.

There may be norms and practices that develop within specific industry sectors within occupational groups and at certain workplaces. For example, De Preter, Mortelmans, and Van Looy (2012), analyzing data from the European Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, reported that older workers in the industrial and financial sectors retire earlier than those in the service sector.

2.3 Quality of Employment

Scholars have devoted significant attention to the relationships between factors at the so-called “micro levels” (for example, employees’ demographic information, family and household characteristics, etc.) and the “macro-levels” (including relevant public policy and economic trends and episodes). However, in light of current trends of older adults extending their labor force participation, additional attention needs to be focused on the relationships between employees’ work experiences and their intent to retire.

In the human resource management (HRM) literature, there is a stream of inquiry that examines the effect of employer-sponsored policies and programs on employees’ attitudes toward work, their productivity, and their overall well-being (see Edgar, Geare, Halhjem, Reese, & Thoresen, 2015). As we have discussed in other publications (e.g., Pitt-Catsouphes & McNamara, in press), scholars have articulated a number of different frameworks and theories to explain these relationships, paying particular attention to the dynamic interactions among employees’ abilities, interests, and competencies; job demands; and the range of resources that employees might access to respond to expectations at work and possible stress (see Demeroutik, Bakker, Nacheiner, & Schaufeli, 2001; Ilmarinen, 2009b; Karasek & Theorell, 1990).

The 2017 Guidelines for Measuring the Quality of Work Environment published by the OECD organizes 17 characteristics of the work environment into six clusters: (a) the physical and social environment (physical risk factors, physical demands, intimidation or discrimination at the workplace, social support at work); (b) job tasks (work intensity, emotional demands, task discretion or autonomy); (c) organizational characteristics (organizational participation and workplace voice, good managerial practices, task clarity, and performance feedback); (d) worktime arrangements (unsocial work schedule, flexibility of work hours); (e) job prospects (perceptions of job insecurity, training and learning opportunities, opportunity for career advancement); and (f) intrinsic aspects (opportunities for self-realization, intrinsic rewards). Warr (1994) proposes a framework of job quality that highlights job characteristics that help to explain variation in job satisfaction, including: autonomy and personal control, opportunities to use one’s skills, physical safety, task variety, respect and status associated with the significance of work tasks, competitive compensation and benefits, the supportiveness of one’s supervisor, clear communications about job expectations and performance, and a positive social environment at the workplace. Based on information gathered from workers age 40 and older in Australia, Oakman and Wells (2016) report that job satisfaction is negatively associated with the intended time of retirement.

Smyer, Besen, and Pitt-Catsouphes and Smyer and Pitt-Catsouphes (Smyer, Besen, & Pitt-Catsouphes, 2009; Smyer & Pitt-Catsouphes, 2007) highlight the financial and non-financial reasons associated with older adults’ intentions to extend their work lives. It is possible to consider that the presence of these factors, such as work environments that structure positive social interactions, creates a “stickiness” that might foster the postponement of retirement or intended retirement (rather than a “slipperiness” toward a more precipitous retirement).

The Sloan Center on Aging & Work at Boston College adapts existing models of the quality of employment, focusing on those aspects of the work experience that employers have the capacity to strengthen if they want to improve employee well-being as well as employee performance: (1) promotion of constructive relationships at the workplace; (2) fair, attractive, and competitive compensation and benefits; (3) culture of respect, inclusion, and equity; (4) opportunities for training, learning, development, and advancement; (5) workplace flexibility, autonomy, and control; (6) provisions for employment securities and predictability; (7) opportunities for meaningful work; and (8) wellness, health, and safety protections at the workplace (Pitt-Catsouphes, McNamara, & Sweet, 2015; see also http://www.bc.edu/research/agingandwork/about/qualityEmploy.html). In previous studies, we have found that survey respondents—including those age 50 and older—are likely to report that each of these dimensions of the quality of employment are “moderately/very important” to them (Pitt-Catsouphes et al., 2015).

Constructive Work Relationships

Over the past decade, there has been increasing awareness about the importance of social health. For people who have had full-time career jobs, workplace relationships can contribute to the size (and in some cases strength) of their social networks. The loss of social relationships can become a particular concern for older employees who worry about social isolation after they retire, especially if a significant proportion of their social relationships (at least their satisfying relationships) are workplace-based. Social isolation and extreme loneliness have been identified by some public health specialists as risk factors for both mental health and physical health (see Valtorta, Kanaan, Gilbody, Ronzi, & Hanratty, 2016). Having a supportive boss and having very good friends at work are associated with the level of job satisfaction of employees age 50 and older (Maestas, Mullen, Powell, von Wachter, & Wenger, 2017).

Fair, Attractive, and Competitive Compensation and Benefits

Compensation and benefits represent the most tangible aspect of the employer–employee contract. Research conducted by Pitt-Catsouphes et al. (2015) found a statistically significant compared to the percentage of older men (87.6%) who report that this aspect of the quality of employment is important to them compared to the men (79.5%). Data from the 2015 American Working Conditions Survey indicates that more than 80% employees (of all ages) say it is important to them to have a job that enables them to provide financial support to their families. Employees age 50 and older are more likely than their younger counterparts to indicate that pension and retirement benefits are important to them (Maestas et al., 2017).

Culture of Respect, Inclusion, and Equity

Work roles can be a fundamental aspect of a sense of identity. Findings reported by Silver and Williams (2016) suggested that at least some career-centric older adults might postpone the transition to retirement.

Diversity experts have long noted that perceptions of respect, inclusion, and organizational fairness are associated with the level of employee engagement and job satisfaction (Pitts, 2009). Many of the assumptions and concepts about respect, inclusion, and dignity that have been used to understand the work experiences of employees in specific protected groups (for example, people from underrepresented racial and ethnic groups, women, people with disabilities) can also help provide insights about older employees who work in age-diverse teams. Pitt-Catsouphes et al. (2015) found that the male respondents age 50+ to one survey were significantly less likely to report that the culture of respect, inclusion, and equity was “moderately or very important” to them (69.5%) compared to their female counterparts (83.6%).

Opportunities for Training, Learning, Development, and Advancement

Human resource management (HRM) experts recognize that quality training programs that strengthen employees’ job-relevant competencies and skills offer benefits both to the employees and to the organization. Researchers have found relationships between employees’ access to training and career development opportunities and levels of job satisfaction (see Grawitch, Gottschalk, & Munz, 2006).

Survey data indicate that younger employees are more likely than their older counterparts to report that training and development are “very important” to them (e.g., Maestas et al., 2017). Discussing the findings of one study, Pitt-Catsouphes et al. (2015) report a gender difference in the importance that older workers attributed to training and development. Women age 50+ (80.9%) were more likely than their male counterparts (71.5%) to indicate that training, development, and advancement were moderately or very important to them. Importantly, the ability to acquire skills was a significant predictor of job satisfaction among workers age 50 and older in the 2015 American Working Conditions Survey. Unfortunately, this study also found that older employees are somewhat less likely to report that they have jobs that allow them to learn “new things” than are younger employees (Maestas et al., 2017).

Workplace Flexibility, Autonomy, and Control

There are several ways to consider how jobs and work tasks are structured. The Center on Aging & Work focuses on two aspects of this quality of employment: (a) flexible work policies that include options available to employees and their supervisors for the scheduling of work time and choices about the place of work; and (b) the predictability of when and how much an employee is expected to work and the extent to which employees have input into those decisions.

The term “workplace flexibility” often refers to formal and informal work arrangements that allow employees and their supervisors some discretion in work structures including: when an employee works (that is, their work schedules which could be standard or non-standard hours that are either “fixed” or could vary under some specified circumstances); where an employee works (for example, at a satellite location or working remotely from home); and how much an employee works (for example, reduced-hours or part-time work; Hill et al., 2008). This aspect of the quality of employment aligns with the job demands, control, and resources models of job characteristics (see Karasek & Thorell, 1988). Maestas et al. at RAND found that less than one in five (17.3%) of employees age 50+ report that they can determine their own work hours (Maestas et al., 2017, p. 24). Pitt-Catsouphes et al. (2015) report a positive relationship between older workers’ reports of work engagement and their satisfaction with their access to workplace flexibility, autonomy, and control.

The term “worktime predictabilities” focuses our attention on the extent to which employees can anticipate (and make plans for) upcoming work schedules and the total number of work hours in a specified period (such as during a work week or work month). Hourly wage workers—particularly those with family caregiving responsibilities—can find it extremely stressful if work schedules change from week to week, often with little or no notice. In addition, expectations for working extra hours can introduce physical fatigue. Furthermore, employees who are assigned fewer hours expected can result in financial stress. Lambert, Halely-Locke, and Henley have contributed significantly to this body of knowledge (Lambert, Halely-Locke, & Henley, 2012).

Provisions for Employment Security and Predictability

Over the course of their work careers, many baby boomers found that their employers changed the narrative about the implied employer–employee contract, replacing notions of job security with ideas about employment security. The idea of job security suggests that employees are likely to continue to have a job with their current employer for the long term (but not necessarily the same job) unless there is a serious breach of contract (for example, consistently poor performance) or unless the company moves, is purchased, or is dissolved. In contrast, employment security is typically understood to be a goal for employees who are expected to seek opportunities to develop portable competencies and skills that could help them secure employment at different organizations if they leave their current employer (voluntarily or not).

Several recent historical events (including the emergence of the gig economy and contingent work arrangements, technological innovations that reduce demand for some types of labor due to increased efficiencies, and the globalization of certain sectors of the economy that are associated with off-shoring of labor) have re-focused researchers’ attention on the importance of employment security. The meaning and significance of job security can be quite different for older workers than younger workers. In part, this is related to theories that connect age to perceptions of “time left” (e.g., Carstensen, 2006). In the context of work and the timing of retirement, reflections about “time left” is less on expected life span than on career sustainability. While some younger workers might anticipate that they have both time and resilience to transition to new jobs (whether they are unemployed by choice or involuntarily), older workers might worry about ageism that could constrain opportunities for moving to a new situation. Pitt-Catsouphes et al. (2015) found that satisfaction with an employer’s provisions for employment security and predictability was related to older workers’ reported levels of engagement.

Opportunities for Meaningful Work

The construct of meaningful work has been defined in different ways. Some scholars have focused on person-job fit and evaluated the extent to which job assignments offer employees opportunities to leverage their experience, skills, and competencies. This perspective associates “meaningfulness” to the contributions that employees can make to overarching organizational goals. Other researchers connect the construct of meaningfulness to personal values and intrinsic rewards or to a greater social purpose that may extend beyond meeting profit objectives of the bottom line (see discussion in Lavine, 2012, pp. 54–55). Several researchers have begun to examine the phenomenon of “encore work” among older adults who pursue social-purpose work (paid or unpaid) during late career or retirement (see Moen, 2016; Pitt-Catsouphes, McNamara, James, & Halvorsen, 2017).

The 2015 American Working Conditions Survey (Maestas et al., 2017) found approximately one fourth of all employees felt it was “very important” that their job was “morally, socially, personally, or spiritually significant” (p. 50). Furthermore, older adults are more likely to report that their work provides them with a “feeling of doing useful work,” with a higher percentage of workers age 50 and older stating this (71.1%) compared to those under the age of 35 (56.2%) or between 35 and 49 (59.1%). Research has found a relationship between perceived meaningfulness of work and job satisfaction among employees 50 and older (Maestas et al., 2017) as well as relationships with the level of older workers’ work engagement (Pitt-Catsouphes et al., 2015).

Wellness, Health, and Safety Protections at the Workplace

Wellness at the workplace can be of particular concern to employees who are exposed to risky and stressful work situations, as well as those who have health conditions or are at risk for declining health. Ilmarinen (2009a, 2009b) and his colleagues have developed the concept of “workability” as one way to think about the physical demands (as well as emotional and cognitive demands) associated with specific jobs at particular workplaces. From this perspective, it is possible to consider how changes in the job or the work environment might reduce the pressure on some older employees to retire. Oakman and Wells (2016) report that employees with lower levels of self-reported workability are more likely to report that they intend to retire earlier.

One of every five (19.8%) employees age 50 and older state that it is important to them that their jobs are not physically demanding (compared to 14.7% of those under 50; Maestas et al., 2017). A study conducted by the Center on Aging & Work at Boston College found that while approximately three fourths of women age 50+ indicated that wellness, health, and safety protections were important to them, only 59.6% of men in that age group agreed (Pitt-Catsouphes et al., 2015).

3 Research Questions

For the study discussed in this chapter, we focused on two research questions:

-

Which aspects of quality of employment are associated with variation in employees’ intent to retire?

-

To what extent does employees’ reported well-being moderate the relationship between their assessments of the quality of employment and their intent to retire (ages 50+ only)?

4 Methods

From 2012 to 2013, the Sloan Center on Aging & Work conducted a randomized intervention project, The Time and Place Management Study, at a large healthcare organization (“ModMed”). The overall study entailed a randomized control trial of the management of time and place at the workplace. The partner organization (which we named “ModMed”) was motivated to participate in the intervention study due to its commitment to quality employment and its desire to be recognized (internally and externally) as a “good place to work.”

Large national and international surveys can provide important insights about emerging trends as well as new understandings about the employees’ experiences. However, they are not typically designed to gather information at the organizational level about the workplace environment. Studies such as the Time and Place Management Study, which we discuss in this chapter, offer opportunities to gather information from a large number of employees within a single firm. This approach helps to “keep the organizational context” more or less constant (see discussion in Kowalski & Loretto, 2017).

4.1 Sample

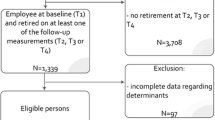

For this study, we used a subsample of data from the baseline survey (September–October 2012) and the wave 3 survey (March–April 2013) from the Time and Place Management Study to explore the relationships between the eight dimensions of the quality of employment and employees’ intent to stay or intent to retire. To be included in the sample, respondents needed to: (a) have participated in the baseline survey (n = 3950); (b) as employees rather than managers (n = 3545); (c) at ages 22 to 65 (n = 2824); (d) have provided follow-up data at wave 3 (the subsequent employee survey; n = 1818); (e) have had valid data on the intent to retire/leave variables at follow-up (n = 1607); and (f) have valid data on predictors at baseline (n = 1606).

The respondents worked for a large healthcare organization; recognizing the gendered nature of many healthcare occupations, we were not surprised that the respondents were overwhelmingly female (84%). One third (36.4%) of the respondents were ages 50–65.

4.2 Measures

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable focused on intent to stay with the current employer and asked employees, “How long do you think you will continue to work for [name of employer]?” The response options included: 5 years or less (I will probably leave before I retire); more than 5 years (but I will probably leave before I retire); until I retire; indefinitely—I do not plan to retire.

A second question, included in the descriptive statistics, focused on employees’ expectations for their work situations 5 years in the future, “Thinking ahead 5 years, what do you expect your work situation to be?” The response options included: working at my current job for [current employer]; working at a new full-time job for [current employer]; working at a new part-time job for [current employer]; working at a new full-time job with another organization; working a new part-time job with another organization; working as a temporary worker hired for projects; self-employed/independent contractor or consultant; retired; full-time homemaker; out of the labor force for another reason.

Predictors

To measure satisfaction with quality of employment, we used a series of Likert-type items that asked respondents to rate “How satisfied are you with the following at [your place of work]?” using a response scale from 1 “Very dissatisfied” to 6 “Very satisfied.” Items included covered eight dimensions of quality of employment:

-

Promotion of constructive relationships at the workplace (1 item): satisfaction with “Clear and effective promotion of constructive relationships.”

-

Fair, attractive, and competitive compensation and benefits (2 items): satisfaction with “Your compensation” and “Benefits that have monetary value such as retirement benefits, paid time off, paid sick days or medical leave, and health insurance.”

-

Culture of respect, inclusion, and equity (1 item): satisfaction with “Clear and effective promotion of respect, inclusion, and diversity.”

-

Opportunities for development, learning, and advancement (1 item): satisfaction with “Opportunities for learning and development.”

-

Wellness, health, and safety protections workplace (1 item): satisfaction with “Health and wellness resources.”

-

Flexibility, autonomy, and control (1 item): satisfaction with “Provision of flexible work options that can adjust when and where work is performed.”

-

Provisions for employment security and predictabilities (2 items): satisfaction with “Your job security” and “Clear and effective information in respect to employment security.”

-

Opportunities for meaningful work (1 item): satisfaction with “Opportunities to engage in meaningful work.”

Moderators and Controls

For our multivariate analyses, we controlled for age, gender, care responsibilities (i.e., whether reported responsibilities for child under 19 years), elder care responsibilities, and the job type (i.e., whether the respondent provided direct health care as a job responsibility). Furthermore, since the intervention for the overall Time and Place Management study was implemented between baseline and wave 3, we controlled for the intervention.

In light of previous findings that quality of employment was associated with employee well-being (Pitt-Catsouphes & McNamara, in press), we explored whether measures of well-being might moderate relationships between employees’ perceptions of the quality of employment and intent to stay or intent to retire. The composite measure of well-being focused on two of the dimensions of well-being: physical and psychological wellness (see discussion in Danna & Griffin, 1999). For each dimension, we asked respondents “How would you rate your [physical/mental] health these days, on a scale from 0 ‘Worst possible health’ to 10 ‘Best possible health.’”

4.3 Analyses

We conducted univariate analyses to gain insights about our sample and bivariate analyses to assess the relationships among the eight dimensions of the quality of employment. First, we used regression analyses to determine the extent to which the quality of employment variables explained variance in employees’ reports of their intent to stay and intent to retire. We then ran a separate regression analysis to examine these relationships among those employees age 50 and older.

5 Findings

Descriptive Statistics

As shown in Table 19.1, respondents under the age of 50 were more likely to indicate that they would be in their current job or in a new full-time job at the same organization in 5 years, compared to those 50–65 years. About one fifth (20.2%) of the respondents between 50 and 65 years of age anticipated that they would retire in the next 5 years.

Table 19.2 shows frequencies of respondents who were satisfied with quality of employment. Overall, most respondents were moderately or very satisfied with each aspect of quality of employment. They were most likely to be moderately or very satisfied with job security (82.4%), opportunities to engage in meaningful work (81.4%), and health and wellness (79.0%), and least likely to be satisfied with compensation (57.0%) and flexible work options (59.2%).

Generally, when differences in satisfaction were significant between age groups, older workers were slightly more likely to be satisfied. For instance, 71.2% of workers ages 50–65 were satisfied with clear and effective promotion of constructive relationships compared to 67.6% of those ages 22–49. Differences between older and younger workers were more pronounced for compensation and benefits that had monetary value. Overall, 70.9% of older workers were moderately or very satisfied with benefits, compared to 61.0% of younger workers. Job security was the only dimension for which younger workers were slightly but significantly more likely to be satisfied than older workers. Differences in satisfaction with learning and development and flexible work options were not significant.

The physical and mental scores (not shown) could range from 1 (worst possible health) to 10 (best possible/perfect health). Overall, the scores were skewed to the positive in this sample. Nearly 8 of every 10 employees had physical health scores of “7” or higher. Interestingly, in this sample, compared to their younger counterparts, higher percentages of those age 50–65 had relatively high physical health scores (that is, scores of “8” or “9”). The differences by the two age groups in the distribution of the physical health scores were statistically significant. As with the physical health self-assessments, the mental health scores for this sample skewed toward the positive, with over half (54.6%) reporting scores of “9” or “10.”

Multivariate Models

In a set of multinomial logistic regression analyses predicting intent to retire, we addressed two separate questions:

-

1.

Which aspects of quality of employment are associated with variation in employees’ intent to retire?

-

2.

To what extent does employees’ reported well-being moderate the relationship between their assessments of the quality of employment and their intent to retire (ages 50+ only)?

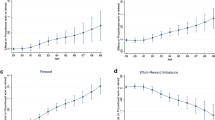

Table 19.3 shows the results of a multinomial logistic regression predicting intent to retire, including all controls except well-being and including all aspects of quality of employment (standardized) together. Compared to “until I retire,” employees who were less satisfied with compensation (−0.17, p < .001), opportunities to engage in meaningful work (b = −0.23, p < .05), and clear and effective information in respect to employment security (b = −0.22, p < .05) were more likely to expect to stay 5 years or less. Lower satisfaction with meaningful work was also associated with intent to stay more than 5 years, but not until retirement.

Table 19.4 shows a multinomial logistic regression including only respondents ages 50–65. This exploratory analysis included only interaction terms with well-being significant at p < .05 in preliminary models. We found that among older workers, well-being moderates the relationship between satisfaction with compensation and intent to turnover. At the mean of well-being, satisfaction with compensation is associated with a lower risk of intended turnover within 5 years (as opposed to remaining with the organization until retirement). At lower well-being (−1 standard deviation), the relationship between compensation and intended turnover within 5 years is more strongly negative. At higher well-being (+1 standard deviation), the relationship between compensation and intended turnover within 5 years is close to 0.

6 Conclusion

It has been complicated to conduct comprehensive research about older adults’ intent to retire, in part because the decision to transition into retirement reflects the interaction of a number of different factors at the individual, family, organizational, and societal levels. However, the findings of our exploratory study suggest that it is important that older adults—at least those who are able to remain in the labor force and who want to do so—have opportunities to work at “quality” jobs that “fit” with needs and priorities. Quality jobs can reduce the numbers of older adults who slip into retirement even though they may have wanted to work longer. Our results suggest that this factor is particularly important for older adults who are vulnerable in terms of physical and mental well-being. For those with lower levels of well-being, compensation and benefits are more important in reducing turnover.

References

Beehr, T. A., Glazer, S., Nielson, N. L., & Farmer, S. J. (2000). Work and nonwork predictors of employees’ retirement ages. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 57(2), 206–225. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1999.1736

Carstensen, L. (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science, 312(5782), 1913–1915. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127488

Coile, C. C., & Levine, P. B. (2006). Bulls, bears, and retirement behavior. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 59(3), 408–429. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979390605900304

Congdon-Hohman, J. (2015). Love, toil, and health insurance: Why American husbands retire when they do. Contemporary Economic Policy, 33(1), 118–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12060

Danna, K., & Griffin, R. W. (1999). Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Management, 25(3), 357–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639902500305

De Preter, H., Mortelmans, D., & Van Looy, D. (2012). Retirement timing in Europe: Does sector make a difference? Industrial Relations Journal, 43(6), 511–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2338.2012.00699.x

De Preter, H., Van Looy, D., Mortelmans, D., & Denaeghel, K. (2013). Retirement timing in Europe: The influence of work and life factors. The Social Science Journal, 50(2), 145–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2013.03.006

Demeroutik, E., Bakker, A., Nacheiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Dudel, C., & Myrskylä, M. (2017). Working life expectancy at age 50 in the United States and the impact of the Great Recession. Demography, 54(6), 2101–2123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-017-0619-6

Edgar, F., Geare, A., Halhjem, M., Reese, K., & Thoresen, C. (2015). Well-being and performance: Measurement issues for HRM research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(15), 1983–1994. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2015.1041760

Grawitch, M. J., Gottschalk, M., & Munz, D. C. (2006). The path to a healthy workplace: A critical review linking healthy workplace practices, employee well-being, and organizational improvements. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 58(3), 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/1065-9293.58.3.129

Greenwald, L., Copeland, C., & VanDerhei, J. (2017). The 2017 Retirement Confidence Survey: Many workers lack retirement confidence and feel stressed about retirement preparations. EBRI Issue Brief, No. 431, pp. 1–32. Retrieved from https://www.ebri.org/pdf/surveys/rcs/2017/IB.431.Mar17.RCS17..21Mar17.pdf

Gupta, D. N., & Larsen, M. (2010). The impact of health on individual retirement plans: Self-reported versus diagnostic measures. Health Economics, 19(7), 792–813. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1523

Gustman, A. L., Steinmeier, T. L., & Tabataba, N. (2012). Did the recession of 2007–2009 affect the wealth and retirement of the near retirement age population in the Health and Retirement Study? Social Security Bulletin, 72(4), 47–67. Retrieved from https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v72n4/v72n4p47.html

Hershfield, H. E. (2011, October). Future self-continuity: How conceptions of the future self-transform intertemporal choice. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1235, 30–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06201.x

Hill, E. J., Grzywacz, J. G., Allen, S., Blanchard, V. L., Matz-Costa, C., Shulkin, S., et al. (2008). Defining and conceptualizing workplace flexibility. Community, Work and Family, 11(2), 149–163.

Ilmarinen, J. (2009a). Aging and work: An international perspective. In S. J. Czaja & J. Sharit (Eds.), Aging and work: Issues and implications in a changing landscape (pp. 51–73). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press.

Ilmarinen, J. (2009b). Work ability—A comprehensive concept for occupational health research and prevention. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 35(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1304

Johnson, R. W. (2004, November). Retirement timing of husbands and wives. Benefits and Compensation Digest, 41(11), 14–19.

Karasek, R., & Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. New York: Basic Books.

Kowalski, T. H. P., & Loretto, W. (2017). Well-being and HRM in the changing workplace. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28(16), 2229–2255.

Lambert, S. J., Haley-Lock, A., & Henly, J. R. (2012). Schedule flexibility in hourly jobs: Unanticipated consequences and promising directions. Community, Work & Family, 15(3), 293–315.

Lavine, L. (2012). Exploring the relationship between corporate social performance and work meaningfulness. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 2012(46), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.9774/gleaf.4700.2012.su.00005

Lilly, M. B., LaPorte, A., & Coyte, P. C. (2007). Labor market work and home care’s unpaid caregivers: A systematic review of labor force participation rates, predictors of labor market withdrawal, and hours of work. Milbank Quarterly, 85(4), 641–690. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00504.x

Lumsdaine, R. L., & Vermeer, S. J. C. (2015). Retirement timing of women and the role of care for grandchildren. Demography, 52(2), 433–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-015-0382-5

Maestas, N., Mullen, K. J., Powell, D., von Wachter, T., & Wenger, J. B. (2017). Working conditions in the United States: Results of the 2015 American Working Conditions Survey. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Retrieved from www.rand.org/t/RR2014

McFall, H. B. (2011). Crash and wait? The impact of the great recession on the retirement plans of older Americans. American Economic Review, 101(3), 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.3.40

Mermin, G. B., Johnson, R. W., & Murphy, D. P. (2007). Why do boomers plan to work longer? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 62B(5), S286–S294. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.5.S286

Moen, P. (2016). Encore adulthood: Boomers on the edge of risk, renewal, & purpose. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Munnell, A. H., & Sass, S. A. (2008). Working longer: The solution to the retirement income challenge. Washington, DC: The Bookings Institution Press.

O’Rand, A. M., & Farkas, J. I. (2002). Couples’ retirement timing in the United States in the 1990s: The impact of market and family role demands on joint work exits. International Journal of Sociology, 32(2), 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15579336.2002.11770247

Oakman, J., & Wells, Y. (2016). Working longer: What is the relationship between person–environment fit and retirement intentions? Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 54(2), 207–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12075

OECD. (2018, January). Ageing and employment policies: United States 2018. Working better with age and fighting unequal ageing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264190115-en

Olesen, S. C., Butterworth, P., & Rodgers, B. (2012). Is poor mental health a risk factor for retirement? Findings from a longitudinal population survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(5), 735–744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0375-7

Peetz, J., & Wilson, A. E. (2008). The temporally extended self: The relation of past and future selves to current identity, motivation, and goal pursuit. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(6), 2090–2106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00150.x

Pitt-Catsouphes, M., & McNamara, T. (in press). Quality of employment and well-being: Updating our understanding and insights. In R. Burke & A. Richardsen (Eds.), Creating psychologically healthy workplaces. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pitt-Catsouphes, M., McNamara, T., & Sweet, S. (2015). Getting a good fit for older employees. In R. J. Burke, C. L. Cooper, & A.-S. G. Antonoiou (Eds.), The multigenerational and aging workforce: Challenges and opportunities (pp. 383–407). Cheltenham, UP: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pitt-Catsouphes, M., McNamara, T., James, J., & Halvorsen, C. (2017). Innovative pathways to meaningful work: Older adults as volunteers and self-employed entrepreneurs. In J. McCarthy & E. Parry (Eds.), Age diversity and work (pp. 195–224). London: Palgrave-Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-46781-2

Pitt-Catsouphes, M., McNamara, T., & Sweet, S. (2015). Getting a good fit for older employees. In R. J. Burke, C. L. Cooper, & A.-S. G. Antonoiou (Eds.), The multigenerational and aging workforce: Challenges and opportunities (pp. 383–407). Cheltenham, UP: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Pitts, D. (2009, March–April). Diversity management, job satisfaction, and performance: Evidence from U.S. Federal Agencies. Public Administration Review, 69(2), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.01977.x

Rogowski, J., & Karoly, L. (2000). Health insurance and retirement behavior: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Survey. Journal of Health Economics, 19(4), 529–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6296(00)00038-2

Ross, M., & Wilson, A. E. (2002). It feels like yesterday: Self-esteem, valence of personal past experiences, and judgments of subjective distance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(5), 792–803. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.82.5.792

Saad, L. (2016, May 23). Three in ten workers foresee working past retirement age. Gallup. Retrieved from http://news.gallup.com/poll/191477/three%60-workers-foresee-working-past-retirement-age.aspx

Sargent-Cox, K. A., Anstey, K. J., Kendig, H., & Skladzien, E. (2012). Determinants of retirement timing expectations in the United States and Australia: A cross-national comparison of the effects of health and retirement benefit policies on retirement timing decisions. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 24(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2012.676324

Silver, M. P., & Williams, S. A. (2016). Reluctance to retire: A qualitative study on work identity, intergenerational conflict, and retirement in academic medicine. The Gerontologist. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw142

Smyer, M. A., Besen, E., & Pitt-Catsouphes, M. (2009). Boomers and the many meanings of work. In R. Hudson (Ed.), Boomer Bust? The new political economy of aging (pp. 3–16). New York: Praeger.

Smyer, M. A., & Pitt-Catsouphes, M. (2007). The meanings of work for older workers. Generations, 31(1), 23–30.

Solem, P. E., Syse, A., Furunes, T., Mykletun, R. J., De Jange, A., Schaufel, W., et al. (2016). To leave or not to leave: Retirement intentions and retirement behavior. Ageing and Society, 36(02), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X14001135

Strahan, E. J., & Wilson, A. E. (2006). Temporal comparisons and motivation: The relation between past, present, and possible future selves. In C. Dunkel & J. Kerpelman (Eds.), Possible selves: Theory, research, and application (pp. 1–15). Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Szinovacz, M. E., DeViney, S., & Davey, A. (2001). Influences of family obligations and relationships on retirement: Variations by gender, race, and marital status. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/56.1.s20

Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S., & Hanratty, B. (2016). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart, 102(13), 1009–1016. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790

Warr, P. (1994). A conceptual framework for the study of work and mental health. Work & Stress, 8(2), 84–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678379408259982

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

McNamara, T., Pitt-Catsouphes, M. (2020). The Stickiness of Quality Work: Exploring Relationships Between the Quality of Employment and the Intent to Leave/Intent to Retire. In: Czaja, S., Sharit, J., James, J. (eds) Current and Emerging Trends in Aging and Work. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24135-3_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24135-3_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-24134-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-24135-3

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)