Abstract

In this chapter, we use a biopsychosocial perspective to highlight how the experience and expression of anger, as well as skills to regulate anger, develop from complex transactional processes across time and are associated with various aspects of adjustment or maladjustment. In particular, our goals are to (1) provide a discussion of the definition and functional significance of anger; (2) describe the development of anger, including its expression and regulation, at the behavioral and biological levels and within the context of interpersonal relationships; (3) provide a selective review of the links between the expression and regulation of anger and adjustment in terms of externalizing and internalizing behavior problems, social and academic adjustment, and aspects of physical health; and (4) discuss challenges for future research.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Anger is one of the earliest emotions that humans develop. As a naturally occurring phenomenon, anger is a part of most individuals’ everyday experiences in response to, and in an attempt to overcome, obstacles to desired objects, individuals, and events (e.g., Barrett & Campos, 1987; Saarni, Campos, Camras, & Witherington, 2006). Despite the consistent role that anger plays across development, considerable change takes place in terms of its presence and intensity, especially from infancy through adolescence (Braungart-Rieker, Hill-Soderlund, & Karrass, 2010; Cole et al., 2011; Denham, Lehman, Moser, & Reeves, 1995; Larson & Asmussen, 1991; Putnam, Gartstein, & Rothbart, 2006; Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey, & Fisher, 2001). Moreover, there is a wide variation in the intensity and frequency of anger experiences and expressions across individuals, as well as how the experience of anger is managed, ranging from constructive strategies to avoidance to aggressive behavior. Thus, although anger can serve adaptive purposes, inappropriate levels and/or expressions of anger may engender behaviors that can incur long-term costs, such as negatively influencing social interactions, preventing adaptive problem-solving, contributing toward the development of mental health difficulties, and/or negatively affecting one’s physical health (e.g., Barefoot, Dodge, Peterson, Dahlstrom, & Williams, 1989; Casey & Schlosser, 1994; Cole, Teti, & Zahn-Waxler, 2003; Eisenberg, Fabes, Nyman, Bernzweig, & Pinuelas, 1994).

In this chapter, we employ a biopsychosocial perspective (Calkins, 2011) to highlight the idea that the experience and expression of anger, as well as skills to modulate anger, develop from complex transactional processes within the individual and between the individual and his/her environment and across time. Importantly, a biopsychosocial perspective incorporates a conceptual integration of processes that are measurable across biological, behavioral, and social levels of analysis to account for developmental patterns of child adjustment within the child’s social context. Thus, this perspective highlights the importance of multilevel work that accounts for the processes associated with children’s development of anger expressions and its regulation, within the context of families and the broader environment, while also acknowledging the important contributions of underlying biological processes. We believe that such a perspective is needed to understand both normative and nonnormative developmental processes associated with anger.

Using a biopsychosocial perspective as a guide, we begin with a discussion of the definition and functional significance of anger. We then describe the development of anger, including its expression and regulation, at the behavioral and biological levels and within the context of interpersonal relationships. This discussion includes acknowledgment of the normative development of anger, as well as important individual differences in its expression and regulation, from infancy through adolescence. We then provide a selective review of the links between the expression and regulation of anger and adjustment in terms of externalizing and internalizing behavior problems, social and academic adjustment, as well as aspects of physical health. We end with a brief discussion of challenges for future research.

Definition of Anger

Typically, anger is associated with discrete facial and bodily expressions including bodily tensing, an arched back, furrowed brow, and/or a squaring of the mouth (Alessandri, Sullivan, & Lewis, 1990; Izard, 1977), and its expression is widely considered to be the result of psychological or physical interference with a goal-directed activity (Izard, 1977; Lewis, Ramsay, & Kawakami, 1993). For instance, individuals feel anger when their efforts toward obtaining a goal or reward are hindered. And, feelings of anger arise when individuals feel as though what “ought” to happen does not, in fact, occur (Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009; Depue & Lacono, 1989; Frijda, 1986). Most emotion theories connect anger to approach motivation (i.e., movement toward the perceived source of the anger) and the association between anger and approach motivation is thought to be bidirectional (Angus, Kemkes, Schutter, & Harmon-Jones, 2015). Thus, not only does anger occur when approach behavior is blocked, but the reverse also occurs, such that feelings of anger may motivate the individual to approach the source of anger. Indeed, in line with a functionalist perspective of emotions, a primary purpose of anger is to overcome obstacles in order to achieve one’s goals (Barrett & Campos, 1987; Saarni et al., 2006), such that feelings of anger may motivate the individual to approach the source of anger. For example, anger may promote behavior to remove the violation of what “ought” to be, as an effort to reopen the path of the desired goal, such as when an angry child attempts to get a toy that has been taken from her.

Behavioral and neurophysiological research provides evidence that anger is associated with increased approach behavior and reward-related motivation (Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009; Harmon-Jones, 2007; Harmon-Jones, Harmon-Jones, Abramson, & Peterson, 2009; van Honk, Harmon-Jones, Morgan, & Schutter, 2010). Neurophysiological work with adults highlights the relation between anger and asymmetrical frontal cortical activity associated with approach motivation using the electroencephalogram (EEG) methodology. Contrary to the previous work that confounded affective valence (positive vs. negative affect) with motivational direction (approach vs. withdrawal), Harmon-Jones and Allen (1998) found that trait anger was associated with increased left frontal activity and decreased right frontal activity during resting baseline, which is commonly associated with approach behavior. Moreover, experimental manipulations indicate that state anger is associated with relative left frontal activation (Harmon-Jones & Sigelman, 2001). Thus, these and additional studies (e.g., Carver & Harmon-Jones, 2009; Harmon-Jones, 2004; Harmon-Jones & Allen, 1998) suggest that anger is associated with approach motivation to blocked goals.

Behavioral investigations also provide support for the association between anger and approach behavior. For example, infant anger during goal blockage was associated with increased behavior (e.g., arm pulling) to overcome an obstacle and increased positive emotions once the obstacle was removed (Lewis & Ramsay, 2005; Lewis, Ramsay, & Sullivan, 2006; Lewis, Sullivan, Ramsay, & Alessandri, 1992). Results from these studies suggest that anger may maintain and increase task engagement and approach motivation. Moreover, correlational behavioral studies indicate that infants prone to experience anger also exhibit strong approach tendencies (Derryberry & Rothbart, 1997; Fox, 1989; Kochanska, Coy, Tjebkes, & Husarek, 1998). For example, anger observed in a laboratory task designed to elicit anger/frustration at 10 months of age was positively associated with parental report of approach at 7 years of age. In addition, 2–5-year-old children who displayed anger in a frustrating context showed greater approach behaviors when aiming to overcome obstacles (He, Xu, & Degnan, 2012). In sum, behavioral and neurophysiological work provides evidence for the association between anger and approach tendencies across the life span, thereby supporting the central theorized function of anger.

The Development of Anger

Despite the consistent functional role that anger plays across the life span, considerable change takes place in terms of its emergence and intensity. Displays of distress and irritability, but not anger, are evident from birth. Although there are different perspectives as to when discrete anger is discernable (Bennett, Bendersky, & Lewis, 2002, 2004; Camras, 1992, 2004; Izard, 1977, 2004; Oster, 2005), most emotion theorists agree that discrete anger is detectable by 6 months of age. Normatively, the average level of expressed anger is relatively low in early infancy but then increases in late infancy and through the second year of life, before declining across toddlerhood and into early childhood (Braungart-Rieker et al., 2010; Denham et al., 1995; Putnam et al., 2006). Indeed, it is common to see toddlers tantrumming in a grocery store aisle because they are not allowed to hold a box of cookies or a preschooler defiantly telling his mother than he is not leaving the park given the normalcy of toddler’s occasional expressions of intense anger (Potegal, Kosorok, & Davidson, 1996). However, a central part of adaptive emotional development is for these anger expressions (frequency, duration, intensity) to decline from toddlerhood into early childhood (Cole et al., 2011). The average level of anger does not change across middle childhood (Deater-Deckard et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2010), but it increases again in preadolescence and adolescence (Larson & Asmussen, 1991). For instance, it is considered normative for adolescents to show frequent expressions of anger, ranging from indignation and resentment to rage, especially toward parents who are seen by the adolescent as limiting their independence.

Various explanations, all involving the emergence of developing abilities and skills, have been posed as to why normative expressions of anger change across development. For example, increased cognitive abilities across infancy and toddlerhood allow children to better understand that a goal has been blocked and that they are capable of mobilizing efforts to alter the situation. Moreover, during this period of development, children become better able to communicate their wants in response to a frustrating situation, although sometimes in an inappropriate manner (Lewis, Alessandri, & Sullivan, 1990). In addition, as will be discussed in greater detail below, important self-regulatory abilities develop across infancy and into childhood that likely explain, at least in part, the decrease in anger across this developmental period. Similarly, increases in anger across the adolescent period have been explained by a lag in developing cognitive self-regulatory abilities (Steinberg, 2004), as well as the frustration that ensues from parental attempts to constrain their growing autonomy.

Importantly, although anger is experienced and expressed by nearly everyone, there are significant individual differences in the expression of anger that complicate our understanding of its normative development. These individual differences are often discussed as reflecting, at least in part, a child’s temperament, defined as early emerging, relatively stable individual differences in the realms of affectivity, activity level, attention, and self-regulation (Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Shiner et al., 2012; Stifter & Dollar, 2016). From a temperament perspective, individuals are prone to experience and express emotions and behaviors, such as anger reactivity, at different frequencies and intensities across situations. For example, when a parent removes an object that the child should not be playing with, some children show intense displays of anger, such as screaming and hitting, whereas others remain calm and move on to another activity. Thus, there are some individuals who are prone to experience low levels of anger from infancy onward, whereas other individuals are quick to experience anger at intense levels and frequencies.

In a seminal study on anger reactivity (Calkins, Dedmon, Gill, Lomax, & Johnson, 2002), infants were classified as easily frustrated or less easily frustrated based on multiple laboratory tasks designed to elicit anger/frustration. The easily frustrated infants were less attentive and more active, as well as more reactive physiologically and less able to regulate physiological reactivity than less easily frustrated infants, thus highlighting early individual differences in anger reactivity and associated behaviors/physiology. More recently, Brooker and colleagues (2014) found evidence for three groups of children based on their anger expressions across infancy: a low-anger group, a high-anger group, and an increasing-anger group. Infants in the low-anger group showed low anger at 6 and 12 months of age across various tasks. Infants in the high-anger group displayed decreasing anger from 6 to 12 months of age; however, infants in this group had expressions of anger that remained high relative to other children across time. Finally, infants in the increasing-anger profile expressed moderate levels of anger at both time points but also showed relative increases in anger between the 6- and 12-month assessments. This pattern of anger expression is what would be expected to occur normatively across this period. Thus, results from these studies, and numerous others, highlight that from infancy there are important variations in an individual’s tendency to experience and express anger.

In sum, significant developmental patterns occur in terms of the experience and expressions of anger across the life span. Moreover, there are individual differences in children’s expressions of anger, such that some children are prone to experience more frequent and/or intense bouts of anger (i.e., yelling, tantrumming, hitting) than others. Children who show high stable expressions of anger across development are at greater risk for difficulties across a variety of realms (e.g., Cole et al., 2003; Denham et al., 2002; Eisenberg et al., 2001). The prevailing perspective is that children who are quicker to experience intense anger without the ability to modulate that arousal are more likely to engage in maladaptive behaviors (Vitaro, Brendgen, & Tremblay, 2002). Thus, although anger serves an adaptive purpose (Barrett & Campos, 1987) and it is important to remember that anger is not inherently problematic, it is critical that children learn how to deal with blocked goals in an appropriate manner. Thus, we now turn to a discussion on the importance of anger regulation.

The Regulation of Anger

One of the most significant aspects of social and emotional development is the acquisition of skills that allow children to modulate anger and other negative emotions (Blair & Diamond, 2008). Although intense expressions of anger are considered typical toddler behavior (Potegal et al., 1996), frequent and/or intense expressions of anger by preschool- and school-age children are problematic (Cole, Zahn-Waxler, & Smith, 1994; Shaw, Bell, & Gilliom, 2000). The normative changes that take place in the experience and expression of anger can be attributed, at least in part, to developmental changes in emotion regulation abilities (Kopp, 1989). For example, developmental periods when anger is generally higher, such as in toddlerhood and early adolescence, are followed by periods of rapid growth in self-regulatory abilities in childhood and late adolescence.

Drawing from theoretical and empirical work in the developmental (Cole, Martin, & Dennis, 2004) and clinical fields (Keenan, 2000), we define emotion regulation as those behaviors, skills, and strategies, whether conscious or unconscious, automatic or effortful, that serve to modulate, inhibit, and enhance emotional experiences and expressions (Calkins & Leerkes, 2011). The acquisition of such skills is a central developmental task that promotes context-appropriate behavior and supports social relationships (Kopp, 1989), both of which are underlying components of adaptive psychological functioning. Across infancy and early childhood, remarkable growth occurs in children’s ability to regulate emotional arousal, including anger. Biological changes, including neurobiological changes in adrenocortical and parasympathetic systems and development in the prefrontal cortex (Hostinar & Gunnar, 2013), significantly contribute to infants’ developing regulatory abilities. Infants’ early efforts to modulate emotions are regulated largely by primitive mechanisms of self-soothing, such as sucking and turning one’s head away (Kopp, 1982). In the second half of the first year, infants develop the ability to voluntarily control arousal largely by attentional control and the engagement of simple motor skills (Posner & Rothbart, 2000).

By the second year of life, infants are more independent in their regulatory abilities (Calkins & Dedmon, 2000). These skills, in addition to the ability to comply with caregiver directives and requests, are supported by significant development of other emotional, motor, language, and cognitive abilities (Kopp, 1989). For instance, improved language abilities assist children to more constructively regulate anger by appropriately expressing their needs with words and to think before acting when frustrated (Cole, Armstrong, & Pemberton, 2010). Children’s regulatory abilities become more flexible in preschool, thereby promoting their ability to regulate behavior through context-appropriate emotions, plan suitably, and process social information accurately (Thompson, Lewis, & Calkins, 2008). Compared to infants and toddlers, children express less frequent anger in early childhood (Denham, 1998), and it becomes more context-dependent and context-appropriate. Additionally, for most children, temper tantrums and physical aggression decrease over preschool age and early childhood (Lemerise & Dodge, 2008; NICHD ECCRN, 2004; Shaw, Gilliom, Ingoldsby, & Nagin, 2003; Tremblay, Masse, Pagani-Kurtz, & Vitaro, 1996). A recent study highlights the important developmental changes that occur in children’s expressions of anger and regulatory abilities (e.g., self-initiated distraction); when children were 18 and 24 months old, on average, they had quick angry reactions and were slower to distract themselves than at later ages. But, by 36 and 48 months of age, children were quicker to use distraction, and anger expressions were briefer and occurred later in the task (Cole et al., 2011).

By elementary school age, children are aware that they are expected to regulate anger within the peer group (Underwood, 1997), and behaving angrily toward peers is associated with increased peer rejection, peer victimization, and/or becoming a bully or victim of a bully (Eisenberg et al., 2005; Hanish, Kochenderfer-Ladd, Fabes, Martin, & Denning, 2004; Salmivalli & Nieminen, 2002). Emotion regulation abilities, including those used to modulate anger, continue to be important in middle childhood and adolescence. As children develop increased attentional abilities, memory, and cognitive function in middle childhood, regulatory strategies become more internal and cognitively based (Kopp, 1982). Indeed, the improvements that occur in the regulation of anger and other emotions across childhood take place in conjunction with improvements in attention and cognitive abilities (i.e., executive function, Posner & Rothbart, 2007), as well as more adaptive behavioral strategies to regulate anger.

At this point in development, children are better able to use active and planful regulatory strategies, such as reframing situations and distracting themselves from frustrating situations (Kalpidou, Power, Cherry, & Gottfried, 2004). It is thought that these abilities are especially important during this developmental period, because new academic and social challenges are presented, and the ability to successfully emotionally regulate assists the child to meet these new challenges. For example, the ability to successfully regulate anger lowers the likelihood that a child will act out and behave destructively in the school context or internalize negative emotions that could lead to increased anxiety or depression. Anger regulation abilities may also assist a child to attend to multiple perspectives during challenging social interactions, possibly resulting in stronger friendships and being better liked by her peers. By adolescence, children can identify long-term consequences of their behavior and thus are better able to decide when to use long- or short-term strategies to regulate their emotions (Moilanen, 2007). In addition, most adolescents can engage in sophisticated regulation strategies, both verbal and facial, to hide their anger in front of peers to behave in an appropriate manner and meet social goals (Shipman, Zeman, & Stegall, 2001).

Importantly, although emotion regulation abilities are discussed as progressively improving across time, some developmental transitions, such as during late childhood into adolescence, may result in a normative deviation from a linear increase in self-regulatory abilities. For instance, emotional arousal may be heightened in adolescence because neither the self-regulation nor risk/reward systems are fully mature (Steinberg, 2004). It has been argued that rapidly developing subcortical brain areas and hormonal changes that accompany puberty enhance sensitivity to reward in adolescence, whereas prefrontal cortical areas that underlie self-regulation are still developing, and this developmental asynchrony may increase some adolescents’ vulnerability to emotion-related risk-taking behaviors (Casey & Caudle, 2013).

In sum, dramatic growth occurs in emotion regulatory abilities across early development, explaining, at least in part, the normative patterns of anger expressions. From a biopsychosocial perspective, it is essential to acknowledge how children’s expression and regulation of anger develop within the context of families and the broader environment, as well as acknowledging the important contribution of underlying biological processes (Calkins, 2011). Therefore, we now turn to a discussion of biological and environmental influences on children’s expression and regulation of anger.

Factors Influencing the Expression and Regulation of Anger

Biological Factors

Empirical and theoretical work has highlighted the underlying biological components (i.e., genes, neural, cardiovascular) of individual differences in the expression and regulation of anger using a variety of physiological measures. For instance, in anatomical and functional animal and human research, the amygdala and superior temporal sulcus regions of the brain have been shown to be involved in processing information relevant to anger. In addition, the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and the prefrontal cortex are involved in experience, rumination, expression, and regulation of anger (Denson, Pedersen, Ronquillo, & Nandy, 2009; Grandjean et al., 2005). As previously discussed, there has also been significant work that links neural activation to individual’s experience and expression of anger. For instance, EEG research in adult samples has shown particular patterns of neural activity associated with anger, such that anger and approach motivation are associated with increased left frontal cortical activity and decreased right frontal cortical activity during resting baseline (e.g., Harmon-Jones & Allen, 1998; Harmon-Jones & Sigelman, 2001).

There is also a substantial body of work within the developmental literature that highlights the parasympathetic nervous system as playing a significant role in the regulation of anger, as well as the regulation of attention, cognition, and other emotions. The myelinated vagus nerve (i.e., tenth cranial nerve) provides input into the heart, producing dynamic changes in cardiac activity that allow the body to transition between sustaining metabolic processes and generating responses to the environment (Porges, 2007). Vagal regulation of the heart when the individual is emotionally challenged has been of interest to researchers studying emotion regulation.

This body of work has largely focused on children’s vagal regulation during laboratory situations that elicit anger (e.g., Calkins & Dedmon, 2000; Calkins, Graziano, & Keane, 2007). During situations that do not present a challenge, the vagus nerve inhibits the sympathetic nervous system’s influence on cardiac activity through increased parasympathetic influence, thereby creating a relaxed and restorative state (Porges, 1995). When an external or emotionally taxing demand is placed on the child, such as when the child is angered, vagal influence is withdrawn or suppressed, resulting in increased sympathetic activity. This modulated increase in sympathetic influence leads to an increase in heart rate and the focusing of attention, which is required for effective emotional responding (Bornstein & Suess, 2000). In this way, the withdrawal of PNS influence during anger-inducing, challenging situations, as evidenced by decreased vagal activity, can be used as an indicator of an individual’s physiological regulation of anger. Greater vagal regulation during infancy and early childhood is most often associated with adaptive outcomes, such as greater behavioral regulation (e.g., Calkins & Dedmon, 2000) and fewer behavior problems (e.g., Graziano & Derefinko, 2013).

There is also evidence of underlying genetic contribution to individual differences in infants’ and children’s expression of anger from behavioral genetics studies involving twins and adoptees (e.g., Deater-Deckard, Petrill, & Thompson, 2007; Gagne & Goldsmith, 2011; Goldsmith, Buss, & Lemery, 1997; Saudino, 2005). For example, Gagne and Goldsmith (2011) reported significant genetic influences on anger reactivity as assessed by parents, as well as anger coded by trained observers in the lab. Overall, this body of research suggests that 40–70% of the variance in trait-level/temperamental anger is heritable. Evidence for the genetic contribution to trait-level anger also comes from molecular genetic studies. For instance, the underlying biology of anger and aggression has implicated the dysregulation of serotonergic activity (e.g., Virkkunen & Linnoila, 1993), although this association may function differently for males and females (Suarez & Krishnan, 2006). The dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) gene has also been implicated as a candidate gene for anger, along with additional temperamental traits (Saudino, 2005). In addition, the norepinephrine system receptor gene ADRA2A (Comings et al., 2000) and the TBX 19 gene (Wasserman, Geijer, Sokolowski, Rozanov, & Wasserman, 2007) have been implicated as candidate genes for trait anger.

This growing body of work suggests that trait-level anger is moderately to substantially heritable; but, identification of specific genes that account for the genetic variance is challenging for a variety of reasons including small effect sizes, difficulty with replication, and gene x gene and gene x environment interactions that create individual differences in temperamental anger (e.g., Pickles et al., 2013). Importantly, although one’s biology is thought to significantly influence individual differences in anger, children learn about the appropriate expression and regulation of anger within the context of caregiver-child interactions, as well as the peer context; thus, we now move to a discussion of how the anger expressions are influenced by the social environment.

Socialization and the Environment

Extensive research highlights that although the expression and regulation of anger is grounded in early biological influences, these emotional responses are also significantly shaped by environmental influences. Caregivers, in particular, are faced with an important role to teach children how to express and regulate anger, as well as other emotions, in a manner that is culturally appropriate and socially adaptive (Lengua & Wachs, 2012). Indeed, it is widely accepted that caregiving practices may support or undermine development and thus contribute to observed individual differences among young children’s emotional abilities (Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007; Thompson, 1994). Interactions with parents in emotion-laden contexts teach children that the use of particular strategies may be more useful for the reduction of emotional arousal than other strategies (Sroufe, 1996). Moreover, the degree to which caregivers appropriately read and respond to infants’ distress in ways that minimize arousal or elicit positive interaction allows the infant to learn from and integrate these experiences into an emerging behavioral repertoire of regulatory capacities (Calkins, Perry, & Dollar, 2016). For example, when parents help a child to modulate anger by shifting her attention from a toy that she desires but cannot have, they help her cope with the experience of anger and, ultimately, teach her that distraction is not only a socially appropriate strategy but one that may also be effective in similar situations that she may later encounter on her own.

Although multiple aspects of the caregiving environment are thought to contribute to children’s expression and regulation of emotions, including anger (Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998; Morris et al., 2007), the attachment relationship between caregivers and infants is hypothesized to be especially significant (Bowlby, 1969/1982). Secure attachment relationships, which are developed through sensitive and supportive caregiver responses to the infant especially in times of stress or external threat, increase children’s expectations about their own ability to respond to environmental challenges. Further, a secure attachment relationship is believed to increase the infant’s expectations that the caregiver will be available and successful at reducing the child’s arousal if needed. In turn, the shift from dyadic to the child’s ability to self-regulate is thought to develop through increased exploration and confidence in their own skills to engage in and navigate emotionally charged situations (Sroufe, 1996).

Empirical evidence supports the important influence that the attachment relationship has in promoting appropriate expressions and methods of regulating anger. For instance, mother-infant attachment security was associated with more positive and less negative affect expressions in the laboratory tasks designed to elicit frustration and fear, suggesting more adaptive emotion regulation among secure children (Smith, Calkins, & Keane, 2006). In addition, infants in a secure attachment relationship were less likely than infants classified as insecurely attached-avoidant to show high negative affect and defiance in compliance task in toddlerhood (NICHD ECCRN, 2004). In studies examining maternal behavior thought to be reflective of insecure attachment relationships (i.e., intrusive, controlling behavior), maternal negative and controlling behavior was associated with less adaptive regulatory strategies in a frustrating task (Calkins, Smith, Gill, & Johnson, 1998). One can expect that, for example, if an overcontrolling parent removes a young child from a situation where, for a successful peer interaction, she needs to control her emotions/behavior in order to share a toy, she may not develop the skills to navigate that situation in socially appropriate ways when a parent is not present.

Additional work has examined how parents socialize children’s expression and regulation of emotions, including anger, through such mechanisms as parental modeling, contingent reactions to children, and teaching mechanisms (Denham, Bassett, & Wyatt, 2007; Eisenberg et al., 1998; Morris et al., 2007). For instance, intense and frequent expression of anger within parent-child interactions is associated with lowered abilities to appropriately regulate anger and aggressive behaviors (Denham, Mitchell-Copeland, Strandberg, Auerbach, & Blair, 1997; Rubin, Burgess, Dwyer, & Hastings, 2003; Smeekens, Riksen-Walraven, & van Bakel, 2007; Snyder, Stoolmiller, Wilson, & Yamamoto, 2003). Research on the role of caregiver reactions to children’s emotions, parents’ nonsupportive, has shown that negative reactions to children’s anger were related to maladaptive outcomes (Eisenberg, Fabes, & Murphy, 1996; Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1996). For example, if a parent dismisses or discourages a child’s expression of anger, he might learn to think of all experiences of anger as “bad” and, therefore, suppress and/or miss opportunities to learn how to regulate anger. Parents’ negative reactions to children’s anger are also likely to intensify children’s emotional arousal, thereby increasing the likelihood that these children will engage in dysregulated behavior. Finally, through conversations parents can discuss the causes and consequences of emotions. In these conversations parents may teach their children strategies for regulating emotion, such as taking a deep breath, thinking of something positive, or redirecting their child’s attention from the source of the anger. Therefore, children of parents who encourage talking about emotions may be better emotion communicators and better able to regulate emotional arousal (Gottman et al., 1997).

Extensive work has considered how different parenting behaviors may be especially important for anger-prone children who might have difficulty otherwise developing these skills (Calkins et al., 1998). For example, sensitive parenting behaviors are thought to help easily frustrated children to develop appropriate regulatory abilities, possibly by identifying anger and strategizing ways that they can deal with that anger, thus facilitating greater social skills for emotionally reactive children. On the other hand, intrusive, controlling, and/or hostile caregiving behavior may exacerbate the child’s proneness toward anger, lowering the likelihood that they learn how to appropriately regulate their affect, which may lead to behavior problems (Bates, Pettit, Dodge, & Ridge, 1998). Thus, the effects of negative parenting behaviors likely are especially detrimental to anger-prone children, given that low-quality and negative parenting seem to amplify behaviors already at risk (Calkins & Fox, 2002; Morris et al., 2002). Recently, Kochanska and Kim (2012) provided important empirical evidence regarding the mechanisms for anger-prone children’s developmental trajectories. In insecurely attached dyads, children who were anger-prone elicited more power-assertive discipline from their parents; in turn, the power-assertive discipline was associated with greater levels of antisocial behavior later in development. However, in relationships characterized by security, variations in children’s anger were not associated with parent’s power-assertive behavior, and, in turn, power assertion was not associated with antisocial behavior.

Importantly, entry into the formal school environment drastically alters the people that children interact with the most. Moreover, given children’s desire to be well-liked and the strong peer group norms for the expression and regulation of anger (Lemerise & Dodge, 2008; Parker & Gottman, 1989), peers become increasingly important across development for socializing the expression and regulation of anger. For example, children understand that excessive anger expressions, such as aggressive behavior, are negatively viewed by peers by middle childhood (Shipman, Zeman, Nesin, & Fitzgerald, 2003). The rise of participation in situations with varying social partners presents children with more opportunities to develop sophisticated emotion regulation skills. The time that children spend with their friends allows the opportunity to practice interpersonal skills that are not provided by the parent-child relationship (Laursen, Finkelstein, & Betts, 2001), and maintaining friendships presents the opportunity to develop and practice conflict resolution skills and learn about the outcomes of these strategies (Fonzi, Schneider, Tani, & Tomada, 1997). On the other hand, children who are aggressive and have difficulty regulating anger are considered socially unskilled by their peers, and as a result, these children are less likely to engage in positive peer interactions and develop friendships that provide beneficial socialization opportunities. Indeed, it is important to consider the other side of this socialization process as well; specifically, if children are friends with those who engage in maladaptive behaviors, the friendship may impede anger regulation development instead of serving as a resource. In sum, the expression and regulation of anger is based in early biological influences and continues to develop within the context of social interactions. Importantly, there is an extensive literature highlighting that inappropriate, dysregulated expressions of anger are associated with a host of maladaptive outcomes. We now turn to a selective review of this work.

Anger and Functioning

Although anger can serve an adaptive purpose (Barrett & Campos, 1987; Saarni, Mumme, & Campos, 1998), inappropriate intensities and/or expressions of anger can also lead to aggressive or socially unsuitable behaviors that may incur long-term costs. For example, children who show inappropriate expressions of anger will likely have trouble developing appropriate social skills and thus have greater difficulty interacting with peers and building positive relationships; in turn, lowered social skills may negatively impact children’s subsequent academic competencies as well as put them at risk for engaging in later delinquent, aggressive behaviors. Indeed, intense and/or frequent expressions of anger are associated with a range of maladaptive outcomes ranging from children’s externalizing behaviors, negatively influencing peer interactions, preventing socially adaptive problem-solving abilities, and/or promoting deleterious effects on one’s physical health (Barefoot et al., 1989; Casey & Schlosser, 1994; Cole et al., 2003; Eisenberg et al., 1994). Given the significant role that anger plays in children’s trajectories toward well-being or maladjustment, extensive empirical and theoretical work has examined these associations. We now provide a selective review of this work.

Externalizing Behaviors

Considerable evidence suggests that although externalizing behaviors, defined as aggressive, destructive, and oppositional behaviors, peak around age 2 and show a normative decline across early childhood (Hartup, 1974; Kopp, 1982), some children continue to show high levels of externalizing behaviors beyond childhood (e.g., Campbell, Spieker, Vandergrift, Belsky, & Burchinal, 2010). For example, in our own work, we identified four trajectories of externalizing behaviors from age 2 to age 15: a low/stable group (children who showed low and stable patterns of externalizing behaviors from early childhood into adolescence), a childhood decreasing group (children who showed a normative decline in externalizing behaviors across early childhood and remained low into adolescence), a high/stable group (children who showed an elevated pattern of externalizing behaviors across childhood and adolescence), and a childhood increasing group (children who showed a significant increase in externalizing behaviors starting at age 7 through adolescence) (Perry, Calkins, Dollar, Keane, & Shanahan, 2017). Importantly, high stable levels of externalizing behavior problems are associated with the greatest risk for later maladjustment including conduct disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, social difficulties, school failure, and delinquent behavior (e.g., Campbell, 2002; Campbell, Shaw, & Gilliom, 2000; Fergusson, Lynskey, & Horwood, 1996; Loeber, Farrington, Stouthamer-Loeber, Moffitt, & Caspi, 1998).

Across decades of research, the relation between anger and externalizing behaviors has been reported repeatedly (Eisenberg et al., 2009; Gilliom, Shaw, Beck, Schonberg, & Lukon, 2002; Lemery, Essex, & Smider, 2002; Lengua, 2006; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Hershey, 1994; Rothbart, Derryberry, & Hershey, 2000; Rydell, Berlin, & Bohlin, 2003). Some of the earliest work on the association between anger and externalizing spectrum problems was conducted in clinical or at-risk samples of children (Barron & Earls, 1984; Bates, Bayles, Bennett, Ridge, & Brown, 1991; Campbell, 1990; Shaw, Keenan, & Vondra, 1994). The guiding perspective behind this research was that children who were quick to experience and express anger were more likely to engage in aggressive and destructive behavior. Moreover, these anger-prone children may behave aggressively when provoked due to their tendency to perceive these provocations as hostile in nature (Vitaro et al., 2002).

The association between anger and externalizing behaviors is found in cross-sectional and longitudinal work from infancy through adolescence and beyond. For instance, observed infant frustration is predictive of parent-rated aggression in 7-year-old children (Rothbart et al., 2000). Brooker and colleagues (2014) reported that infants in the high-anger group (based on observations at 6 and 12 months of age) were rated as showing greater behavior problems at age 3 than children in the normative, increasing-anger group (consisting of children who expressed moderate but increasing levels of anger between the 6- and 12-month assessments as would be expected to occur normatively). In preschool, children high in parent-rated anger were more likely to be rated as high in externalizing behavior problems by teachers in preschool and elementary school and by parents at home (Rydell et al., 2003). In addition, high levels of anger at 4.5 years directly predict high levels of conduct disorder symptoms at 6 and 7 years old (Nozadi, Spinrad, Eisenberg, & Eggum-Wilkens, 2015). Importantly, both the intensity and frequency of anger expressions are associated with externalizing symptoms in childhood (Hernández et al., 2015).

Evidence for the association between anger expressions and externalizing behavior problems has also been found into preadolescence and adolescence. In our own work, we found that dysregulated anger at 5 years of age was associated with greater odds of being in a high/stable externalizing trajectory instead of a decreasing externalizing trajectory from age 2 to age 15 (Perry et al., 2017). Wang and colleagues (2016) reported that childhood anger predicted parent reports of externalizing and co-occurring externalizing and internalizing behavior problems. In addition, adolescent anger predicted parent reports of pure externalizing problems, as well as both parent- and teacher-reported co-occurring problems. Thus, there is strong evidence that high levels of anger are dysregulated in nature such that they can impede rather than aid goal pursuit (Cole, Michel, & Teti, 1994), placing individuals at risk for later externalizing behavior problems.

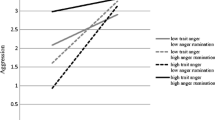

Unfortunately, the association between anger and externalizing behavior problems is not always clear. As noted, there is a normal developmental trajectory in which most children show early expressions of anger and aggression; whereas most children decrease in these aggressive behaviors, other children go on to have behavioral and social difficulties (Campbell, 1990; Tremblay et al., 1999). Considerable work has aimed to identify processes and mechanisms that identify the individual and environmental conditions that contribute to the lowering of anger and aggressive behaviors over time. The moderating effects of emotion and behavioral regulation, in particular, have been examined extensively to explain the association between anger and problem behavior. Notably, Eisenberg and colleagues (e.g., Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, et al., 1996; Eisenberg et al., 1995; Eisenberg et al., 1994, 2001, 2007, 2009; Hernández et al., 2015; Nozadi et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016) have conducted a series of investigations addressing the interaction of negative emotionality/anger and regulatory abilities in the prediction of behavior problems and social difficulties. This program of research has consistently demonstrated that children high in anger but lacking regulatory skills are more likely to develop social difficulties and behavior problems, especially within the externalizing realm.

Evidence for this association has come from other laboratories, as well. Moran and colleagues (2013) found that 3-year-old children with higher levels of observed anger showed higher externalizing behaviors but only when the children had poor regulation skills. Deater-Deckard et al. (2007) found that the link between anger reactivity and aggressive behavior was mediated by children’s regulation of sustained attentive behavior, an important skill used to modulate anger. The regulation of the physiological manifestation of anger has also been examined. For example, greater physiological regulation, as measured by vagal withdrawal, can lower the likelihood that anger-prone children show high levels of disruptive/aggressive behavior from ages 2 to 5 years (Degnan, Calkins, Keane, & Hill-Soderlund, 2008).

Of note, the moderating effect of regulatory abilities is not found for some children (e.g., Nozadi et al., 2015); therefore, additional factors are believed to attenuate or exacerbate risk for anger-prone children’s development of externalizing behaviors. For example, anger-prone children are more likely to interpret others’ cues as angry or hostile in nature when, in fact, they are not; in turn, this maladaptive social information processing is sometimes associated with increased childhood externalizing behaviors (e.g., Dodge, Pettit, Bates, & Valente, 1995). Anger-prone children also may elicit more negative parenting behaviors, which in turn are associated with the development of externalizing behaviors (e.g., Campbell, 1995; Putnam, Sanson, & Rothbart, 2002). First- and second-grade children high in anger were rated as higher in teacher-reported externalizing problems if children viewed their mothers as high in overt hostility (Morris et al., 2002). Lengua (2008) reported that high-frustration children had greater increases in externalizing behaviors across middle childhood within the context of child-reported maternal rejection. Thus, an extensive body of work highlights the association between dysregulated expressions of anger and externalizing behaviors across early development; importantly though, there are important individual (i.e., regulatory abilities) and environmental (i.e., caregiving behaviors) factors that can attenuate or exacerbate this association.

Internalizing Behaviors

Although somewhat counterintuitive, empirical and theoretical work has also indicated that the experience of anger is associated with internalizing difficulties for some children (Eisenberg et al., 2005; Gartstein, Putnam, & Rothbart, 2012; Lemery et al., 2002; Muris, Meesters, & Blijlevens, 2007; Rydell et al., 2003), including symptoms of anxiety and depression, as well as social withdrawal and somatic problems (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1981). Anger is also proposed to contribute to the etiology of anxiety and depression disorders among adolescents and adults (Leibenluft, Cohen, Gorrindo, Brook, & Pine, 2006; Riley, Treiber, & Woods, 1989). Thus, there is growing evidence that the expression of anger is associated with internalizing symptomatology across the life span. However, this association is inconsistent with some studies finding null effects (e.g., Zahn-Waxler, Cole, Richardson, & Friedman, 1994).

There are multiple pathways that may explain how anger is associated with difficulties within the internalizing realm. Carver and Scheier (1998) proposed that sadness and depression can result from an individual repeatedly failing to approach a goal. As such, individuals might initially experience anger when progress toward a goal is blocked, but after continued efforts to obtain this goal are hindered and presumed lost, the internalizing emotion of sadness may develop. Moreover, given that anger-prone individuals are at risk for experiencing increased social challenges and difficulties (Dougherty, 2006; Eisenberg, Fabes, Bernzweig, & Karbon, 1993; Rydell, Thorell, & Bohlin, 2007), children may experience increased sadness from peer rejection and/or conflict with teachers, thereby leading to internalizing difficulties. Similarly, increases in externalizing behavior problems can coincide with increases in internalizing behavior problems (Gilliom & Shaw, 2004). Therefore, anger may be associated with internalizing difficulties through the risk for developing externalizing behavior problems; indeed, some studies find a strong association between anger proneness and co-occurring internalizing and externalizing behavior problems (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2009).

Interestingly, whereas most hypotheses regarding the association between anger and internalizing behaviors propose that tendencies toward anger precipitate the development of internalizing behaviors, the opposite may also be true. For instance, because a child with internalizing behaviors may encounter greater social difficulties as she gets older, in turn she may experience increases in anger over time. Or, these children may experience self-directed anger due to feelings of inadequacy. This line of reasoning suggests that the association between anger and internalizing behaviors develops with age (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2005). Given the lack of empirical work addressing the specific mechanisms and direction of effects regarding the association between anger and internalizing symptomatology, additional work is warranted.

Social Adjustment

Not only is the expression and regulation of anger influenced by social relationships, but it also plays a significant role in the initiation and maintenance of them. There is a rich literature demonstrating that anger-prone children are at a greater risk of social maladjustment, such as lowered social skills, peer relationships, and popularity (Dougherty, 2006; Eisenberg et al., 1993; Ladd & Burgess, 1999; Pianta, Cox, & Snow, 2007; Rydell et al., 2007). For instance, extensive work has focused on the association between anger and children’s social skills (i.e., the ability to respond in an appropriate manner in social situations, sharing and cooperating; Gresham & Elliot, 1990; Rose-Krasnor & Denham, 2009). In theory, children with lower expressions of anger, or those who can appropriately regulate their anger, have an easier time acquiring the capacity to use socially skilled behaviors that improve social interactions and benefit others (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006); in turn, these children will be better able to utilize their social skills in a variety of situations (Eisenberg, Fabes, & Spinrad, 2006). On the other hand, intense expressions of anger may put children at a social disadvantage by increasing the likelihood that they will be rejected by their peers (Pope, Bierman, & Mumma, 1991), and therefore these children will have fewer opportunities to interact with peers and learn and practice social skills. Empirical evidence supports these hypotheses. For example, easily frustrated toddlers experience more conflicts and are less cooperative with peers (Calkins, Gill, Johnson, & Smith, 1999) and the ability to regulate anger is predictive of preschool and elementary school children’s ability to engage in appropriate social skills such as sharing and conflict prevention (Rydell et al., 2003, 2007).

Another commonly studied aspect of social competence, peer group acceptance/rejection, is also associated with children’s expressions of anger. As would be expected, children’s tendency to express intense negative emotions, especially anger, is associated with being rejected and/or excluded by one’s peers from early childhood through adolescence (Eisenberg et al., 1993, 2000; Fabes & Eisenberg, 1992; Kim & Cicchetti, 2010; Szewczyk-Sokolowski, Bost, & Wainwright, 2005; Trentacosta & Shaw, 2009). For example, peer-rejected children expressed more facial and verbal anger than average-status children in the context of losing a game to another child (Hubbard, 2001), and preschool-aged children who were rated as higher in dysregulated negative emotions were more likely to be rejected by their peers (Godleski, Kamper, Ostrov, Hart, & Blakely-McClure, 2015). Indeed, expressions of anger, especially aggressive behavior, are one of the strongest and most consistent behavioral predictors of peer rejection in childhood (Rubin et al., 2006).

There is also growing evidence that anger is associated with peer victimization (Hanish et al., 2004; Jensen-Campbell & Malcolm, 2007; Spence, De Young, Toon, & Bond, 2009), defined as being bullied or aggressed upon repeatedly and over time (Juvonen & Graham, 2014). For example, anger-prone children were more likely to be victimized by peers than other children; interestingly, the display of aggressive behaviors, especially early in the school year, mediated this association for boys (Hanish et al., 2004). In addition, dysregulated negativity (distress, anger/frustration) was associated with more frequent peer victimization both concurrently and across a 6-month period, even after controlling for baseline levels of peer victimization (Rosen, Milich, & Harris, 2012). Thus, extensive empirical evidence highlights that inappropriate expressions of anger are associated with many forms of social maladjustment. Given the significant role that appropriate social competencies play in pathways toward positive adjustment, additional research is warranted to identify processes and mechanisms that may explain these associations.

Academic Adjustment

Another aspect of children’s functioning that has been linked to children’s anger is difficulties within the academic realm. Although a considerable amount of work has considered the association between negative emotionality and academic adjustment (Denham et al., 2012; Gumora & Arsenio, 2002), emerging evidence suggests that intense and/or frequent expressions of anger, in particular, are associated with academic difficulties. For instance, teachers’ reports of children’s anger have been found to be negatively associated with engagement in kindergarten (Valiente, Swanson, & Lemery-Chalfant, 2012), and teachers’ reports of Chinese students’ anger have been reported as associated with lowered GPA (Zhou, Main, & Wang, 2010).

Various hypotheses have been presented to explain this association. For example, anger may negatively influence students’ motivation and enjoyment of school (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun, Elliot, & Maier, 2009). Thus, children who experience intense anger when dealing with a challenging assignment or don’t perform well on a test likely find it more challenging to stay motivated or engaged in school. Anger-prone children also may behave more aggressively with teachers and therefore have lowered social support in the classroom, making school more of a challenge. In addition, anger-prone children may be at a disadvantage in the school setting by way of lowered social abilities. Through lowered development of social skills (Pope & Bierman, 1999; Rydell et al., 2007), anger-prone children likely have fewer supportive peer relationships in the classroom, thus negatively influencing their enthusiasm for school, which would be harmful to their academic competencies. In our own work, we found evidence for this hypothesis (Dollar, Perry, Calkins, Keane, & Shanahan, 2018). Specifically, anger reactivity at age 2 was negatively associated with children’s social skills at age 7; in turn, children’s social skills were negatively associated with teacher report of academic competence and child and teacher report of school problems at age 10. All three indirect effects were significant suggesting that children’s social skills is one mechanism through which toddler anger is associated with academic difficulties. Similarly, anger-prone children may experience academic difficulties through externalizing behaviors. Specifically, externalizing behaviors may limit learning opportunities, as well as increasing the likelihood of being socially rejected or accepted by deviant peers, thereby leading to lowered academic success through a disinterest or expulsion from school (Moilanen, Shaw, & Maxwell, 2010; Schwartz, Gorman, Nakamoto, & McKay, 2006). As can be seen, there is growing evidence to suggest that inappropriate expressions of anger influence academic challenges through various social and psychological mechanisms. In addition, given the well-established link between psychological and physical health, a growing number of studies have considered the role of individual’s emotions, including anger, in pathways toward physical health or a lack thereof. Thus, we now turn to a brief review of the literature linking anger and aspects of physical health.

Physical Health

Intense and/or frequent expressions of anger have been linked to aspects of physical well-being, such as substance use/abuse (e.g., Hussong & Cassin, 1994), cardiovascular disease (CVD; e.g., Harburg, Julius, Kaciroti, Gleiberman, & Schork, 2003), cancer (e.g., Thomas et al., 2000), and elevated blood pressure and heart rate (Hauber, Rice, Howell, & Carmon, 1998). Evidence of these associations begin as early as adolescence and continue throughout adulthood. For example, there is growing evidence that the experience of heightened anger is associated with increased adolescent alcohol and substance use (Hussong & Cassin, 1994); interestingly, anger is more strongly related to alcohol and drug use than other negative emotions (McCreary & Sadava, 2000; Pardini, Lochman, & Wells, 2004). Although the exact mechanisms for this association have yet to be determined, one likely pathway is through adolescents’ social difficulties. In particular, anger-prone individuals are more likely to associate with deviant peers because they are rejected by their peers (Eisenberg et al., 1993, 2000; Kim & Cicchetti, 2010; Trentacosta & Shaw, 2009), thereby increasing the likelihood that these teens will engage in substance use. Moreover, adolescent dysregulated anger has been identified as an important correlate of substance use (Colder & Stice, 1998; Cougle, Zvolensky, & Hawkins, 2013), suggesting that anger-prone individuals may engage in substance use/abuse to deal with their intense experience of emotions and possibly social difficulties. In an important preliminary study, Mischel and colleagues (2014) found that the association between dysregulated anger and smoking was explained through individuals’ motive to smoke as wanting to reduce the experience of negative emotions. Thus, this growing area of work suggests that, similar to psychological and behavioral difficulties, anger-prone individuals’ risk of engaging in substance use can be lessened through the development of appropriate regulatory abilities.

There is also growing evidence of an association between anger and cardiovascular risk (e.g., Gallacher, Yarnell, Sweetnam, Elwood, & Stansfeld, 1999; Kerr, 2008; Kubzansky, Cole, Kawachi, Vokonas, & Sparrow, 2006; Williams, 2010; Williams, Nieto, Sanford, & Tyroler, 2001). Two central hypotheses have been presented to explain the process by which anger is associated with greater CVD (Rozanski, Blumenthal, & Kaplan, 1999). The first explanation involves behavioral and cognitive factors associated with the individual. For instance, an individual that experiences intense feelings of anger may be at a greater risk of developing CVD because he/she engages in poor health behaviors and decisions, such as eating behaviors, exercise, and engagement in substance use/abuse. Or, the association between anger and CVD may be enhanced through cognitive processes, such as rumination, that maintain and increase discomfort, hypertension, and pain (Markovitz, Matthews, Wing, Kuller, & Meilahn, 1991; Miers, Rieffe, Terwogt, Cowan, & Linden, 2007; Schneider, Egan, Johnson, Drobny, & Julius, 1986), such that individuals that experience intense anger are more likely to ruminate about their anger, thereby increasing the likelihood of hypertension, pain, etc. A second explanation suggests a direct physiological mechanism between anger and CVD. Specifically, it has been suggested that hemodynamic and neurohormonal responses of the sympathetic adrenomedullary system and of the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis may explain the association between anger and CVD. Given these important links between anger and aspects of physical health, additional work is greatly needed to empirically identify the mechanisms, especially early in life, that explain how anger is associated with lowered physical health.

Conclusion and Future Directions

In this chapter, we discussed the development of the expression and regulation of anger, in addition to the well-established connection between inappropriate expressions of anger and various maladaptive outcomes. To this end, a biopsychosocial perspective was employed to highlight the importance of the processes associated with children’s anger development within the context of families, while also acknowledging the important contribution of underlying biological processes (Calkins, 2011). We primarily considered a functional perspective on emotional development (Barrett & Campos, 1987; Saarni et al., 2006) given its emphasis on how emotions should be considered processes that are dynamic and relational, which is in line with a biopsychosocial perspective. However, it is important to note that many other theoretical perspectives of emotion exist, each providing important, albeit sometimes different, insights into the nature of emotion, including anger. For instance, the differential emotions theory (DET; Izard, 1971) would propose that certain facial expressions reflect anger, whereas other perspectives may contend that the same expression represents a more general negative affective state (e.g., distress) that does not correspond with the discrete emotion of anger (Camras, 1992). There are also differences among emotion theories regarding what is considered an emotional expression (i.e., facial expressions, emotion-related behavioral responses) that significantly influences one’s interpretation of the current literature on anger development.

It is also important to note that there are varying perspectives regarding the association between emotional activation or reactions and emotion regulation. We, along with others (Campos, Frankel, & Camras, 2004; Cole et al., 2004), view emotion processes as regulatory and inherently regulated such that they are not readily distinguishable from one another and cannot be separated from the social context in which they occur. In other words, emotion and its regulation may best be considered unfolding processes rather than discrete occurrences. However, others posit that it is meaningful to be able to account for the way children regulate their emotional responses (Goldsmith, Pollak, & Davidson, 2008; Ochsner & Gross, 2008); therefore, there are aspects of emotional processes that can be specifically labeled as emotion regulation. Importantly, these varying theoretical perspectives of emotion and emotion regulation may promote different interpretations of the existing work on anger development. For instance, a child’s facial expression of anger in a frustrating context may be interpreted by some as anger, whereas others may argue that the expression and the corresponding psychophysiological and/or neural activity reflect the child’s effort to regulate.

Although the study of anger development has been useful in identifying developmental processes and mechanisms associated with adjustment, many questions remain. Here, we highlight future directions in developmental research that we believe will clarify our understanding of how anger is associated with trajectories of well-being or risk. One important area of future research involves consideration of the similarities and differences between the constructs of anger, frustration, irritability, and aggression, as well as which of these can be considered as an emotion. Some theoretical perspectives, such as DET, consider anger, not frustration, irritability, and aggression, as emotions, whereas other perspectives (e.g., Sroufe, 1996) propose that frustration is a precursor to a more mature emotion of anger. Thus, although many studies on the expression and regulation of anger use the terms “frustration” and “irritability” interchangeably with “anger” as an indicator of emotional functioning, those who subscribe to the DET perspective would argue that frustration and irritability are not, in fact, emotions.

As in many areas of developmental research, semantic and measurement differences make it challenging to synthesize existing empirical work, identify key areas of future inquiries, and inform important prevention and intervention efforts. Moreover, to date, it is not agreed upon if there are qualitative differences between these constructs and if so how they are associated with different developmental trajectories. Similarly, in line with multiple perspectives of emotions (e.g., Izard, 1991), because there are different functions associated with specific negative emotions (i.e., anger, sadness, fear), as well as the fact that they are associated with differing outcomes of interest (e.g., Stifter & Dollar, 2016), we propose that it is important for future work to consider specific negative emotions as opposed to more general measures of negative emotions/emotionality. Answers to these inquiries would greatly clarify work on these associated constructs across the life span.

In addition, too little longitudinal research spans childhood and adolescence, and even fewer studies consider the transitions to and through adulthood. Most research on anger comes from the developmental psychology literature, focused largely on infancy and childhood (although there are a growing number of studies examining adolescence), or the social and personality psychology literature that mainly employs samples of young adults. Thus, there is limited empirical evidence regarding the developmental continuities, processes, and mechanisms associated with the expression and regulation of anger across developmental periods. Although time-consuming and expensive, there is a need for more rigorous longitudinal studies that span multiple developmental periods to fully address the developmental role of anger. Relatedly, it is important for researchers to consider the construct validity and comparison across development when designing and interpreting findings regarding anger. Given the significant differences in normative anger expressions and regulatory abilities across developmental periods, the methodology (i.e., observational, psychophysiological, self-report, other-report) used is often different across development periods. Moreover, the situations that will elicit the experience, expression, and regulation of anger will vary across development. Thus, while ensuring that measures of anger expressions and regulation are developmentally appropriate, future work spanning developmental periods must consider if, and how, these measures are capturing the same processes at different points in development and, therefore, can be compared across time.

Finally, as can be seen from the reviewed literature, there are significant associations between inappropriate expressions of anger and maladjustment across various realms of functioning. Importantly, emerging evidence suggests that not only are psychological, social, academic, and physical health adjustments important outcomes in their own right, but there are complex, dynamic associations between various realms of adjustment (Bornstein, Hahn, & Haynes, 2010; Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004). For instance, a lack of socially competent behavior may play an underlying role in the emergence of behavior problems across development (Hinshaw, 1992), the development of academic challenges for some children (Pianta & Stuhlman, 2004), and/or engagement in risky health behaviors (Helms et al., 2014; Prinstein, Choukas-Bradley, Helms, Brechwald, & Rancourt, 2011). On the other hand, social abilities may be undermined by psychological and behavioral difficulties, as well as a lack of regulatory abilities, such that children behave inappropriately and have difficulties processing social information, thereby disrupting the development of social skills, positive peer interactions, and healthy friendships (Bornstein et al., 2010). Thus, it is likely that there are reciprocal relations between various realms of adjustment, predicted by early tendencies to experience and express intense anger, and we are just starting to address these transactional relations across development. Future work addressing the specifics of these cross-domain associations not only has implications for developmental theory but may elucidate the etiology of challenges in other realms of functioning.

In sum, we have highlighted how a biopsychosocial perspective may illuminate processes and mechanisms that are important for understanding the etiology and developmental trajectories associated with the experience and expression of anger. Although there are a growing number of studies addressing the transactional nature of children’s emotional development, both at the physiological and at the behavioral levels and within the social context, the process by which this development occurs is still largely unknown. For instance, additional work is needed to understand if and how caregivers influence children’s development of physiological regulation, as well as how the development of this physiological regulation influences subsequent social interactions with caregivers and peers. We believe that the use of this perspective in future work will encourage researchers to study mechanisms across and between different levels of children’s social and emotional functioning, which will greatly aid in understanding how these processes are associated with adjustment or alternatively maladjustment in children who experience and express varying levels of anger. Given the significant, and growing, body of work on the associations between intense, possibly dysregulated expressions of anger and maladjustment across psychological, social, academic, and physical realms, a continued study of how and why these associations exist will inform preventative interventions, including determining when and how to best intervene.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Edelbrock, C. S. (1981). Behavioral problems and competencies reported by parents of normal and disturbed children aged four through sixteen. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 46(1), 1–82. https://doi.org/10.2307/1165983

Alessandri, S. M., Sullivan, M. W., & Lewis, M. (1990). Violation of expectancy and frustration in early infancy. Developmental Psychology, 26(5), 738–744. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012

Angus, D. J., Kemkes, K., Schutter, D. J. L. G., & Harmon, J. E. (2015). Anger is associated with reward-related electrocortical activity: Evidence from the reward positivity. Psychophysiology, 52(10), 1271–1280. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12460

Barefoot, J. C., Dodge, K. A., Peterson, B. L., Dahlstrom, W. G., & Williams, R. B. (1989). The Cook-Medley hostility scale: Item content and ability to predict survival. Psychosomatic Medicine, 51(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-198901000-00005

Barrett, K. C., & Campos, J. J. (1987). Perspectives on emotional development II: A functionalist approach to emotions. In J. D. Osofsky (Ed.), Handbook of infant development (pp. 555–578). New York, NY: Guilford Publications, Inc..

Barron, A. P., & Earls, F. (1984). The relation of temperament and social factors to behavior problems in three-year-old children. Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 25(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1984.tb01716.x

Bates, J. E., Bayles, K., Bennett, D. S., Ridge, B., & Brown, M. M. (1991). Origins of externalizing behavior problems at eight years of age. In D. J. Pepler & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), The development and treatment of childhood aggression (pp. 93–120). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., Dodge, K. A., & Ridge, B. (1998). Interaction of temperamental resistance to control and restrictive parenting in the development of externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology, 34(5), 982–995. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.982

Bennett, D. S., Bendersky, M., & Lewis, M. (2002). Children’s intellectual and emotional-behavioral adjustment at 4 years as a function of cocaine exposure, maternal characteristics, and environmental risk. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 648–658. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.648

Bennett, D. S., Bendersky, M., & Lewis, M. (2004). On specifying specificity: Facial expressions at 4 months. Infancy, 6(3), 425–429. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327078in0603_8

Blair, C., & Diamond, A. (2008). Biological processes in prevention and intervention: The promotion of self-regulation as a means of preventing school failure. Development and Psychopathology, 20(3), 899–911. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579408000436

Bornstein, M. H., Hahn, C., & Haynes, O. (2010). Social competence, externalizing, and internalizing behavioral adjustment from early childhood through early adolescence: Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22(4), 717–735. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000416

Bornstein, M. H., & Suess, P. E. (2000). Physiological self-regulation and information processing in infancy: Cardiac vagal tone and habituation. Child Development, 71(2), 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00143

Bowlby, J. (1969/1982). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Braungart-Rieker, J. M., Hill-Soderlund, A. L., & Karrass, J. (2010). Fear and anger reactivity trajectories from 4 to 16 months: The roles of temperament, regulation, and maternal sensitivity. Developmental Psychology, 46(4), 791–804. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019673

Brooker, R. J., Buss, K. A., Lemery-Chalfant, K., Aksan, N., Davidson, R. J., & Goldsmith, H. H. (2014). Profiles of observed infant anger predict preschool behavior problems: Moderation by life stress. Developmental Psychology, 50(10), 2343–2352. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037693

Calkins, S. D. (2011). Caregiving as coregulation: Psychobiological processes and child functioning. In A. Booth, S. M. McHale, & N. S. Lansdale (Eds.), Biosocial foundations of family processes (pp. 49–59). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7361-0_3

Calkins, S. D., & Dedmon, S. A. (2000). Physiological and behavioral regulation in two-year-old children with aggressive/destructive behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28(2), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005112912906

Calkins, S. D., Dedmon, S. E., Gill, K. L., Lomax, L. E., & Johnson, L. M. (2002). Frustration in infancy: Implications for ER, physiological processes, and temperament. Infancy, 3(2), 175–197. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327078IN0302_4

Calkins, S. D., & Fox, N. A. (2002). Self-regulatory processes in early personality development: A multilevel approach to the study of childhood social withdrawal and aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 14(3), 477–498. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457940200305X

Calkins, S. D., Gill, K. L., Johnson, M. C., & Smith, C. L. (1999). Emotional reactivity and emotional regulation strategies as predictors of social behavior with peers during toddlerhood. Social Development, 8(3), 310–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00098

Calkins, S. D., Graziano, P. A., & Keane, S. P. (2007). Cardiac vagal regulation differentiates among children at risk for behavior problems. Biological Psychology, 74(2), 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.09.005

Calkins, S. D., & Leerkes, E. M. (2011). Attachment processes and the development of emotional self-regulation. In K. D. Vohs & R. F. Baumeister (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 355–373). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Calkins, S. D., Perry, N. B., & Dollar, J. M. (2016). A biopsychosocial model of the development of self-regulation in infancy. In L. Balter & C. S. Tamis-LeMonda (Eds.), Child psychology: A handbook of contemporary issues (3rd ed., pp. 3–22). New York, NY: Routledge.

Calkins, S. D., Smith, C. L., Gill, K. L., & Johnson, M. C. (1998). Maternal interactive style across contexts: Relations to emotional, behavioral and physiological regulation during toddlerhood. Social Development, 7(3), 350–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00072

Campbell, S. B. (1990). Behavior problems in preschool children: Clinical and developmental issues. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Campbell, S. B. (1995). Behavior problems in preschool children: A review of recent research. Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines, 36(1), 113–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1995.tb01657.x

Campbell, S. B. (2002). Behavior problems in preschool children: Clinical and developmental issues (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Campbell, S. B., Shaw, D. S., & Gilliom, M. (2000). Early externalizing behavior problems: Toddlers and preschoolers at risk for later maladjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 467–488. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400003114

Campbell, S. B., Spieker, S., Vandergrift, N., Belsky, J., & Burchinal, M. (2010). Predictors and sequelae of trajectories of physical aggression in school-age boys and girls. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409990319

Campos, J. J., Frankel, C. B., & Camras, L. (2004). On the nature of emotion regulation. Child Development, 75, 377–394.

Camras, L. A. (1992). Expressive development and basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion, 6(3–4), 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939208411072

Camras, L. A. (2004). An event-emotion or event-expression hypothesis? A comment on the commentaries on Bennett, Bendersky, & Lewis (2002). Infancy, 6(3), 431–433. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327078in0603_9

Carver, C. S., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2009). Anger is an approach-related affect: Evidence and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013965

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1998). On the self-regulation of behavior. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139174794