Abstract

Children of incarcerated parents are an increasing and significant population, not only in the USA but around the world. An expanding body of rigorous research, particularly over the past decade, has found that children of incarcerated parents are at increased risk for a variety of negative outcomes compared to their peers, including infant mortality, externalizing behavior problems, mental health concerns, educational and developmental challenges, and relationship problems. Moreover, children with incarcerated parents are exposed to more risk factors and adverse childhood experiences than their peers. In this volume, we bring representatives of multiple academic and practice disciplines together to summarize the state of scientific knowledge about the children of incarcerated parents, discuss policies and practices grounded in that knowledge, and offer a blueprint for future research and intervention efforts with this population. The large number of children who have been affected by parental incarceration makes it untenable for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers to ignore these children and their families. This book is our collective attempt to continue to bridge the communication gaps between and among research, practice, and policymaking relevant to children of incarcerated parents, and to encourage the further conduct of high-quality research so that sufficient knowledge will be available for evidence-based practice and policymaking that makes a positive and enduring difference in the lives of children and their families.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Recent estimates indicate more than 5 million children under the age of 14, or 7% of all children in the USA, have experienced a coresident parent leaving to go to jail or prison (Murphey & Cooper, 2015). This is surely an underestimate, as it does not include children with nonresident parents who are incarcerated. The staggering numbers are even more concerning because we now know that parental incarceration is harmful to children, on average, and it has significantly contributed to growing racial and economic disparities that profoundly affect child’s well-being in the USA (Wakefield & Wildeman, 2013, 2018). A growing body of rigorous research has found that children of incarcerated parents are at increased risk for a variety of negative outcomes compared to their peers, including infant mortality, externalizing behavior problems, mental health concerns, educational and developmental challenges, and relationship problems (e.g., Murray & Farrington, 2005; Murray, Farrington, Sekol, & Olsen, 2009; Wakefield & Wildeman, 2013). Children with incarcerated parents are also exposed to more risk factors and adverse childhood experiences than their peers (Murphey & Cooper, 2015).

Although pioneering advocates, practitioners, and researchers have called attention time and again to the families of incarcerated individuals, often referring to affected children and their caregivers as “invisible victims” and “collateral damage” (e.g., Travis & Waul, 2003), it has taken more than two decades to accumulate a substantial body of scientific knowledge about children of incarcerated parents, with much of the research occurring just in the last ten years. As Scharff Smith in Chap. 18 of this volume points out, a recent search for literature revealed that more than 260 new publications on parental incarceration and children of incarcerated parents appeared just in the years between 2012 and 2016.

Despite the large numbers of children and families affected, and the increase in the scientific knowledge base, information about children’s well-being when parents are incarcerated has been slow to enter the public consciousness at large. Even today, a frequent (and erroneous) statistic that appears in the media about these children is that they are five to seven times more likely to be incarcerated as adults than their peers (e.g., Adams-Ockrassa, 2018). While this statement may make a compelling introduction to a news story or a speech, the original source is unknown and no known data verify this claim. For many years, much of what we knew about the children of incarcerated parents came from anecdotes and stories such as this, a few small convenience samples, and a large sample survey of adults incarcerated in prison.

Fortunately, over the past decade this situation has changed rapidly, and the second edition of this book is a testament to the various lines of rigorous inquiry in which numerous scientists and interventionists are now actively engaged. The majority of this work, however, has been conducted within the USA, which has experienced growth in incarcerated populations over successive decades, and currently has the highest incarceration rate in the world (Pew Center on the States, 2009), even though there has been a plateau in growth in recent years (Gramlich, 2018). There is also quite a range in the incarceration rates across states, with Oklahoma now having the highest incarceration rate in the USA, unseating Louisiana from its long-held position as “the world’s prison capital” (Wagner & Sawyer, 2018). In contrast, Connecticut, Michigan, Mississippi, Rhode Island, and South Carolina reduced their prison populations between 14 and 25% over the past decade (Schrantz, DeBor, & Mauer, 2018). Given these facts, the historical, cultural, and political contexts within the USA are important to keep in mind when considering the contemporary findings summarized in this volume.

Although most incarceration in the USA occurs in jails—which are locally run facilities that house individuals detained following arrest, prior to charging or sentencing, and those sentenced for a year or less and typically for misdemeanors (Zeng, 2018)—studies have traditionally focused on children of parents in state or federal prison or made no distinction among types of corrections facilities. Thus, in the previous edition of our book, much of the work summarized pertained to children with imprisoned parents. In the recent past, we have seen changes in this approach, with more attention being given to jailed parents and their children in addition to variables such as the length of the parent’s incarceration, the nature of the parent’s criminal activity, and the effects of parental recidivism on children, especially when multiple incarcerations occur in a relatively short amount of time, which is common for jail incarcerations. It should be noted, however, that several states in the USA do not make a distinction between jail and prison, nor do many other countries.

Despite increases in research quantity and quality, most studies of children with incarcerated parents still focus on contrasting children who have ever experienced parental incarceration with those who have never experienced it. However, parents are involved in the criminal justice system in many ways that may affect children, from their arrest to community supervision (Chap. 3, this volume). The approach of combining children who have ever experienced parental incarceration, despite differences in the length, timing, and number of incarcerations, has helped garner adequate sample sizes to advance what we know about effects of parental incarceration on children, which is a critical step. Unfortunately, this approach also masks nuances in children’s experiences and does not allow detailed examination of effects during different developmental periods or of mechanisms of these effects. Yet this, too, is beginning to change.

Research that Crosses Disciplinary Boundaries

The lives of children affected by parental incarceration may intersect with a variety of social service systems, such as public health and medicine, child welfare, education, mental health, and juvenile and criminal justice. Researchers and practitioners from academic disciplines that, by tradition, are attached to these systems have studied the children of incarcerated parents, but they have usually worked in isolation. In our original 2010 volume (Eddy & Poehlmann, 2010), we argued that this situation must change. Since then, it has changed, albeit quite slowly (cf., Wildeman, Haskins, & Poehlmann-Tynan, 2017). To adequately understand the needs and developmental trajectories of the children of incarcerated parents, research knowledge and practices need to be integrated across each of the relevant academic fields (Wildeman et al., 2017). Thus, a primary goal of this volume is to further stimulate and encourage collaborative, interdisciplinary multimethod research, including basic, intervention, and prevention research focused on the children of incarcerated parents and their families, schools, and communities.

In service of this goal, on these pages, a cross-sectoral approach to understanding the children of incarcerated parents is presented. Representatives from the fields of demography, sociology, anthropology, criminology, family studies, law, public health, social work, nursing, psychiatry, developmental and clinical psychology, prevention science, education and public policy and management contributed chapters, as did corrections, child welfare, and juvenile justice administrators and representatives from various nonprofit organizations serving children and families through direct service, research, and/or advocacy. Further contributions were made by individuals who have personal experiences highly relevant to understanding children with incarcerated parents. Most authors are active researchers residing and conducting studies in the USA. They hail from 17 states and the District of Columbia, representing every major region of the country. International perspectives are provided by researchers from five countries who have been involved in studies throughout the world (Chaps. 6 and 18). By viewing the children of incarcerated parents through a diverse set of lenses, it is our hope that this volume will not only consolidate an interdisciplinary perspective regarding children’s outcomes within the context of parental incarceration, but also foster new collaborative approaches that generate advances in research, practice, and social policy.

Book Themes

Each of the chapters in our 2010 volume was grounded in one or more of five central themes: a developmental perspective, risk and resilience processes, multiple contexts that affect children’s development, implications for policy and practice, and directions for future research. In our new volume, we have retained some of these foci, changed others, and deepened our inclusion of: (a) broader contexts in which children’s development occurs, including additional perspectives from criminal justice, sociology, demography, and policy; (b) key proximal processes that make a difference in the lives of children with incarcerated parents, such as caregiving, parent–child contact, and parent–child separation resulting not only from parental incarceration but also from immigration detention; and (c) personal experiences of those working with and for children with incarcerated parents and their families.

Some children of incarcerated parents are born while their parent(s) are in prison or jail; most affected minor children are less than 10 years of age (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008; Mumola, 2000). However, many adolescents and adult children have experienced their parents’ arrest or incarceration at various points during their lives, and perhaps experienced parental incarceration during more than one developmental period. Because of the dramatically different needs of children of incarcerated parents throughout the life span, a developmental perspective is essential for an adequate understanding of this population. Some of the chapters in this volume emphasize the importance of developmental theory and research as it applies to children whose parents are incarcerated, a focus that has been lacking in much of the previous literature.

Because many children of incarcerated parents experience multiple risks, including separation from parents, poverty, parental substance abuse, and shifts in caregivers, much of the literature focusing on this population has focused on risk and negative outcomes. However, there is much variability in the outcomes of children with incarcerated parents. Many children of incarcerated parents show resilience, defined as the process of successful adaptation in the face of significant adversity (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000). Masten (2001, 2014) has argued that resilience is an ordinary process as long as a sufficient array of normative human adaptational systems remains intact, such as positive parent–child relationships and extended family networks. The adequate maintenance of protective systems can be extremely challenging for children and families impacted by parental criminality and incarceration, and thus fostering resilience processes is a primary goal of many intervention efforts. Some chapters highlight protective factors that can help promote resilience processes in children of incarcerated parents and offer new ideas for intervention and policies that may better assist children and their families.

Like all children, the day-to-day lives of the children of incarcerated parents are imbedded in family, school, and community contexts. Unlike other children, however, the lives of children of incarcerated parents are heavily influenced by a powerful “fourth” context, the criminal justice system (and its ties to the immigration system), which encompasses a wide variety of subcontexts with distinct subcultures, including the police, the courts, jails, prisons, and probation and parole. Of particular importance to consider when interpreting findings about the children of incarcerated parents is the type of setting within which a parent is incarcerated. In this volume, we consider children whose parents are in prison or in jail. Compared to prisons, jails are often located closer to the incarcerated individual’s family members, possibly affecting visitation frequency. Compared to state prisons, there are fewer federal prisons; federal prisoners are under the legal authority of the US federal government (US Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2010), and they are often located far from the incarcerated individual’s family. Policies and procedures regarding visitation and other forms of contact between family members may vary dramatically depending on the type of facility in which the parent is housed. Various chapters highlight specific contexts such as these that may directly or indirectly affect children’s adaptation and development over time, including what is known about how these factors influence the effectiveness of interventions and policies.

Although significant progress has been made in research and intervention over the past decade, there is still much to learn about children affected by parental incarceration and their families. By taking an inventory of current research findings, integrating these findings into a coherent framework, and highlighting knowledge gaps in the literature, this volume offers new directions for research focusing both on child and family development and on interventions designed to ameliorate the negative effects of parental incarceration. Each chapter provides suggestions for areas where further research and applications are needed, and these suggestions are tied together in the final chapter.

Accessing the emerging literature on the children of incarcerated parents can be difficult for policymakers and practitioners. The integrated and rigorous scholarship presented in this volume provides a springboard not only for increased communication among professionals who are interested in the children of incarcerated parents, but also for the generation of new directions in research that can better inform social policies. To this end, many chapters highlight recent research findings and then discuss the potential implications of these findings for public policy and for practice. In the final section of the volume, future directions are discussed, and findings and discussions from throughout the book are tied together in the final chapter.

Book Sections

Current Trends and New Findings

Over the past several decades, fundamental changes have taken place in criminal justice policies in the USA, leading to exponential growth in the number of incarcerated adults in state and federal prisons and jails, with only a recent leveling off (Harrison & Karberg, 2004; Mumola, 2000; Zeng, 2018). Because the majority of incarcerated adults are parents, this phenomenon has led to significant increases in the number of children affected by parental incarceration during the past several decades (e.g., Glaze & Maruschak, 2008; this volume, Chap. 2). In addition to the millions of children and adolescents impacted by the current incarceration of a parent, millions more have parents on probation and parole, many of whom were recently incarcerated (US Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2007). Many additional children have parents in jail, as most incarceration in the USA occurs at the jail level (Wagner & Rabuy, 2017; Wagner & Sawyer, 2018). Indeed, 10.6 million people were admitted to local jails across the USA in 2016, with an average of 731,300 people in jail per day (Zeng, 2018). In addition, although the vast majority of incarcerated parents are fathers, the number of women behind bars continues to grow, with women reaching nearly 15% of the jail population in 2016 (Zeng, 2018). As a result of these combined trends, professionals from all walks of life—whether they be healthcare providers, day care workers, teachers, coaches, or mentors—are more likely to encounter children who have or have had fathers, mothers, and other family members in jail or prison or under correctional supervision than in any prior generation.

The Current Trends and New Findings section of this volume, which includes five chapters, four of which are completely new, provides an important context for the chapters that follow. The chapters are written by sociologists, demographers, and criminologists who have been instrumental in furthering our understanding of parental incarceration and its potential causal role in diminished child well-being and growing social inequality. The authors of Chaps. 2 through 4 discuss a range of current issues, including estimates of children’s and parents’ exposure to incarceration in the USA, stark racial disparities that exist in such exposures, and the wider range of parental criminal justice involvement that potentially affects children, including but not limited to incarceration in jails and prisons. Because African American, Latinx, Native American, and many other children of color are disproportionately affected by parental incarceration, race and ethnicity are presented as key contexts for understanding risk and resilience processes in this population. The section also includes a chapter that summarizes findings from the seminal Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing study, a study of vulnerable families in US cities that has contributed an enormous amount to our knowledge about children and families with incarcerated parents, even though it was not originally designed as a study of such children. The section concludes with a chapter focusing on international research on children with incarcerated parents, which has been instrumental in helping focus and guide research agendas across multiple countries, including in the USA.

Developmental and Family Research

In the second section of the volume, we highlight developmental and family research through five chapters, three of which are completely new. The two revised chapters, which summarize what we know about the development of infants through adolescents when parents are incarcerated, ground the volume in a developmental perspective. Two of the new chapters emphasize family experiences that are particularly important for children with incarcerated parents: caregiving contexts and parent–child visits during parental incarceration. The final chapter in the section highlights the value of the use of qualitative approaches to improving our understanding of the lived experiences and perspectives of children, parents, families, and communities when parents are incarcerated.

Although we have grounded our interdisciplinary perspective in developmental theory and research, the best academic developmental journals still have accepted few articles focusing on children with incarcerated parents (e.g., a 2005 paper in Child Development, and a 2018 paper in Developmental Psychology). Chapters in the Developmental Research section review what is known about the effects and correlates of parental incarceration for children of different ages, focusing on results from recent cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Because most incarcerated mothers and many incarcerated fathers lived with their children before their incarceration (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008) and plan to reunify with their families and children following their release, parental incarceration often results in transitory living arrangements for children. Whereas many children and families strive to maintain contact with the incarcerated parent despite the challenges posed by disrupted living situations, additional stressors, such as financial strain, geographic distance from home to prison, and the ambivalence of family members toward the inmate and visitation, compound the difficulties that families face in remaining connected. Children’s caregivers play a vital role in helping maintain ties between the incarcerated parent and child, and the quality of environments that caregivers provide is critical for children’s cognitive, academic, and social development during the parental incarceration period. Chapters in this section explore these issues in the context of children’s attachment relationships and home environments, interactions with schools and communities, and children’s friendships and peer relations.

Intervention Research

A growing number of interventions have been implemented with incarcerated individuals and their children and families. This body of intervention research is explored in the Intervention Research section of this volume, including a review of findings from studies conducted in prison nursery programs available for women who are pregnant when they enter jail or prison, a review of findings from studies of interventions focusing on improving the communication and parenting skills of incarcerated parents, and a review of findings from studies of mentoring programs for children living in the community. There is growing interest in a multimodal orientation to intervention relevant to the children of incarcerated parents (e.g., Eddy et al., 2008), and thus an organizing framework and findings from experimental and quasi-experimental trials are presented to demonstrate applications of empirically based preventive interventions to incarcerated parents and their children and families. A new chapter in the Intervention section focuses on international policy interventions designed to explore the effects on children of alternatives to incarceration for parents. The introduction of sentencing alternatives to prison or jail is an exciting new development in the field.

Perspectives

In the second edition of the Handbook, we added an entirely new section to better represent the variety of perspectives that exist regarding research and intervention with children of incarcerated parents. The four new chapters in this section focus on a range of issues and perspectives, including the importance of community-based participatory research as a way to empower families of color (Chap. 17) and the delineation of the benefits of collaborating with individuals and communities who have experienced parental incarceration and its effects first hand (Chap. 21). Additional new chapters focus on a children’s rights approach to the reform of criminal justice systems, with encouraging examples from European countries (Chap. 18), and from a US state using data to transform their juvenile justice organization (Chap. 20). In addition, one revised chapter in this section focuses on the interface between parental criminal justice involvement and the child welfare system (Chap. 19).

Future Directions

In recent years, research has begun to play a prominent role in shaping policy and practice at the federal and state levels; this is also beginning to happen at local levels as well, where most incarceration occurs. A variety of governments and institutions have adopted mandates to use “evidence-based” or “evidence-informed” practices, but there remain many details to work out, including how such practices are defined, implemented, monitored, and adapted. The Future Directions section of this volume discusses ways in which research findings might influence future policies, practices, and research relevant to children of incarcerated parents. One entirely new chapter focuses on what we know and do not know in relation to policy-relevant research (Chap. 22). A second new chapter highlights new directions that are needed in research and intervention in the area of detaining, separating, and incarcerating parents and their children at the US southern border (Chap. 23). The suggestions for research and intervention that have been developed in the preceding chapters are tied together in the final chapters (Chaps. 24 and 25), providing students, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers a clear starting place to engage in more successful and comprehensive multidisciplinary work and decision making on behalf of children affected by parental incarceration.

Summary

Children of incarcerated parents are a significant, growing, and vulnerable population. Researchers from multiple disciplines have learned much about this group of children, especially over the past decade. Here, we bring representatives of these fields of study together to summarize the state of scientific knowledge about the children of incarcerated parents, discuss policies and practices grounded in that knowledge, and offer a blueprint for future research. With the number of children who have been affected by parental incarceration to date, it is not tenable for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers to ignore these children and their families. This book is our collective attempt to continue to bridge the communication gaps between and among research, practice, and policymaking relevant to children of incarcerated parents, and to encourage the further conduct of high-quality research so that sufficient knowledge will be available for evidence-based practice and policymaking that makes a positive and enduring difference in the lives of children and their families.

References

Adams-Ockrassa, S. (2018, August 25). Finding the answers at camp. The Register-Guard, A1, A4.

Eddy, J. M., Martinez, C. R., Jr., Schiffmann, T., Newton, R., Olin, L., Leve, L., et al. (2008). Development of a multisystemic parent management training intervention for incarcerated parents, their children and families. Clinical Psychologist, 12(3), 86–98.

Eddy, J. M., & Poehlmann, J. (Eds.). (2010). Children of incarcerated parents: A handbook for researchers and practitioners. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Glaze, L. E., & Maruschak, L. M. (2008). Special report: Parents in prison and their minor children. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Gramlich, J. (2018, May 2). America’s incarceration rate is at a two-decade low. The Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/05/02/americas-incarceration-rate-is-at-a-two-decade-low/ on November 7, 2018.

Harrison, P. M., & Karberg, J. C. (2004, May 27). Prison and jail inmates at midyear 2003. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/pjim03.pdf on August 20, 2018.

Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71, 543–562.

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56, 227–238.

Masten, A. S. (2014). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. New York.

Mumola, C. J. (2000). Special report: Incarcerated parents and their children. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Murphey, D., & Cooper, P. M. (2015). Parents behind bars: What happens to their children? Child Trends, 1–20.

Murray, J., & Farrington, D. P. (2005). Parental imprisonment: Effects on boys’ antisocial behaviour and delinquency through the life course. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 1269–1278.

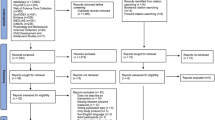

Murray, J., Farrington, D. P., Sekol, I., & Olsen, R. F. (2009). Effects of parental imprisonment on child antisocial behaviour and mental health: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 4, 1–105. Oslo, Norway: Campbell Collaboration.

Pew Center on the States (2009). One in 31: The long reach of American corrections. Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts.

Schrantz, D., DeBor, S. T., & Mauer, M. (2018, September 5). Decarceration strategies: How five states achieved substantial prison population reductions. The Sentencing Project. Retrieved from https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/decarceration-strategies-5-states-achieved-substantial-prison-population-reductions/ on November 7, 2018.

Travis, J., & Waul, M. (2003). Prisoners once removed: The impact of incarceration and reentry on children, families, and communities. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (2007). Probation and parole in the United States, 2006. Retrieved from http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/pandp.htm on November 25, 2008.

U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics (2010). Terms and definitions. Retrieved from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/index.cfm?ty=tda on January 2, 2010.

Wagner, P., & Rabuy, B. (2017). Mass incarceration: The whole pie 2017. Prison Policy Initiative.

Wagner, P., & Sawyer, W. (2018). Mass incarceration: The whole pie 2018. Prison Policy Initiative.

Wakefield, S., & Wildeman, C. (2013). Children of the prison boom: Mass incarceration and the future of American inequality. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Wakefield, S., & Wildeman, C. (2018). How much might mass imprisonment affect inequality? In R. Condry & P. Scharff Smith (Eds.), Prisons, punishment, and families: Towards a new sociology of punishment (pp. 58–72). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Wildeman, C., Haskins, A. R., & Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (Eds.). (2017). When parents are incarcerated: Interdisciplinary research and interventions to support children. Urie Bronfenbrenner series on the ecology of human development. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Zeng, Z. (2018). Jail inmates in 2016. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Eddy, J.M., Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (2019). Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Research and Intervention with Children of Incarcerated Parents. In: Eddy, J., Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (eds) Handbook on Children with Incarcerated Parents. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16707-3_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16707-3_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-16706-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-16707-3

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)