Abstract

Risk disclosure in banking is particularly important for the efficacy of market discipline, the assessment of bank performance, the efficiency of the financial market, and the overall stability of the financial system. The European banking union and the financial crisis have enhanced the strategic role of credit risk disclosure in banking. The topic of this chapter is the evaluation of credit risk disclosure practices in banks’ annual financial reporting. The empirical research is conducted on a sample of ten large Italian banks. The authors employ content analysis and provide a hybrid scoring model for the assessment of credit risk disclosure. The chapter provides empirical findings which reveal significant differences between banks’ credit risk reporting practices, even though they are subject to similar regulatory and accounting frameworks.

Although this chapter has been written jointly by the two authors, it is possible to identify the contribution of each one as follows. Abstract and Sects. 1, 2, 5, and 6 have been written by Enzo Scannella. Sections 3 and 4 have been written jointly by Enzo Scannella and Salvatore Polizzi. The data were analyzed jointly by the two authors. All the figures and tables were prepared jointly by the two authors.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Lending represents the most important business of a commercial bank, and the credit risk of a loan portfolio has a strong impact on bank financial statements in terms of economic performance, liquidity, funding, capital requirements, and the overall solvency and stability (Mottura 2011, 2014a, 2016; Onado 2004; Rutigliano 2011, 2016; Sironi and Resti 2008; Tutino 2013, 2015). It has become increasingly important to measure, manage, assess, and disclose the impact of credit risk in the economics and management of banking institutions (Bessis 2015; Hull 2018; Masera 2005, 2009; Onado 2017).

Credit risk is one of the most relevant kinds of risk in banking. It is one of the main risks in commercial banks, and the ability to manage it affects meaningfully banks’ stability and profitability. “Credit risk is the risk of loss resulting from an obligor’s inability to meet its obligations” (Bessis 2015). It arises from the possibility that borrowers, bond issuers, and counterparties in derivative transactions may default.

The topic of this chapter is the assessment of credit risk disclosure practices in the annual financial reporting of large Italian banks. The authors carry out an empirical study on a sample of the ten largest Italian banks. In this research, the authors employ content analysis as a “research technique for making replicable and valid inferences from texts to the contexts of their use” (Krippendorff 2004), and as “a research technique for the objective, systematic and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication” (Berelson 1952).

The structure of this chapter is as follows. Section 2 introduces credit risk disclosure in banking. It aims to frame the specific nature of credit risk and provides a regulatory and accounting perspective on credit risk in banking. Section 3 provides an innovative metric based on the analytical grids of key credit risk disclosure parameters to evaluate credit risk disclosure in banking. Section 4 analyses the main results of the empirical research on credit risk disclosure in banking and discusses the research findings. Section 5 provides a brief overview of the research findings. Section 6 concludes.

2 Credit Risk Disclosure in Banking: Definition and Regulatory Framework

The main purpose of this research is to evaluate credit risk disclosure practices in banking, with reference to credit risk on loan portfolio. It refers to the risk that a borrower (either retail, corporate, or institutional) defaults on payment obligations in terms of principal and/or interest. This risk stems from the possibility to make losses on loans if the debtors are not able to repay the credits.

The risk factors or components of credit risk can be distinguished into transaction and portfolio levels. At the transaction level, such credit risk components are the following: default risk, exposure risk, recovery risk, and migration risk. The first three risk components characterize the current credit state of a borrower and are mandatory with the capital adequacy regulation (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2006). The migration risk refers to the potential deterioration of the creditworthiness of a borrower. At the portfolio level, the credit risk components are the following: concentration and correlation risk.

A bank’s exposure to credit risk through a loan implies that only the lending bank faces the risk of loss. The assessment of credit risk on loans has to take into account the repayment of both principal and interest.

In 1988, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (1988) issued the first regulatory framework directed toward assessing capital in relation to credit risk (the risk of counterparty failure). This framework takes into account the credit risk on on- and off-balance sheet exposures by applying credit conversion factors to different types of off-balance sheet transactions.

The New Bank Capital Accord (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2006) defines “credit risk components” as the factors that have an incidence on the potential loss from credit risk. Within the New Bank Capital Accord, banks may rely on their own internal estimates of credit risk components in determining the minimum capital requirement for credit exposures. Risk components include probability of default (PD), loss given default (LGD), and exposure at default (EAD). Such credit risk components are significant information inputs of risk-weighted functions that have been developed to determine bank capital requirements and to discriminate among different credit asset classes.

Credit risk disclosure provides market participants and other stakeholders the information they need to make meaningful assessments of a bank’s credit risk profile and investment decisions. Overall, the disclosure of reliable, understandable, accurate, and updated qualitative and quantitative information on banking risk, and credit risk particularly, is the prerequisite to trigger the sequence of conditions that allows financial markets to fulfill their role of effective discipline, in the sense that market prices banking risks more efficiently (Scannella 2018). In a wider perspective, credit risk disclosure strengthens confidence in a banking system by reducing uncertainty in bank assessment and bank performance (Acharya and Richardson 2009; Acharya and Ryan 2016; Crockett 2002; Financial Stability Board 2012; Kissing 2016; Morgan 2002; Nier and Baumann 2006; Onado 2000, 2016). In addition, well-informed creditors and other bank counterparties may provide a bank with strong incentives to maintain sound risk management systems and practices and to conduct a prudent banking business (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2000; Maffei 2017; Malinconico 2007). Hence, the Basel Committee considers the disclosure of banks’ activities and risks inherent in those activities to be a key element of an effectively supervised, safe and sound banking system.

Credit risk disclosure reduces asymmetric information in financial markets and contributes to financial stability and to remove obstacles that prevent market discipline by providing investors and other market participants a better understanding of banks’ risk exposures and risk management practices. On the other hand, banks cannot disclose all the information about their risk exposure and management, because they may want to hide strategic information their competitors might be interested in.Footnote 1 Thus, there is essentially a trade-off problem between transparency and opacity in banking. This is one of the main reasons that support the introduction and imposition of some minimum disclosure standards and transparency constraints in an attempt to balance such trade-off. The regulatory framework concerning credit risk disclosure in banking can be identified as follows: International Accounting Standards/International Financial Reporting Standards (IAS/IFRS), bank capital requirements regulation, and national regulation of annual financial statements of banking institutions.

The adoption of IAS/IFRS aims to enhance the comparability across space and over time of banks’ financial statements. Accounting standards for loans are mainly covered by IFRS 7 (financial instruments: disclosures) and IAS 39 (financial instruments: recognition and measurement). The latter has been largely amended by IFRS 9 (financial instruments) in January 2018. At initial recognition, loans are evaluated at fair value. Subsequently, loans are measured at amortized cost using the effective interest method. IAS 39 permits banks to designate, at the time of acquisition, any loan as available for sale, in which case it is measured at fair value with changes in fair value recognized in equity. In addition, loans are impaired, and impairment losses are recognized, only if there is objective evidence as a result of one or more events that occurred after the initial recognition. IFRS 7 requires disclosure of information about the significance of financial instruments to a bank, and the nature and extent of risks arising from those financial instruments, both in qualitative and quantitative terms. Specific disclosures are required in relation to transferred financial assets and a number of other matters. In particular, IFRS 7 adds new disclosure requirements about financial instruments to those previously required by IAS 32 and replaces the disclosures previously required by IAS 30.

The Basel Capital Adequacy regulation provides a set of requirements for banks.Footnote 2 Its main goal is making the event of a bank bankruptcy less likely. In order to achieve this aim, the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision (2006) has created a three-pillar regulatory framework. Pillar 3 represents a crucial regulatory requirement for risk reporting. This pillar requires banks to prepare a Pillar 3 disclosure report, which gives banks the possibility to disclose a wide range of information on risk exposures and capital adequacy, both from a quantitative and a qualitative point of view. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has recently expanded risk disclosure requirements in order to enhance the consistency of reporting and comparability across banks and enhance market discipline (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2015, 2017).

At the national level, with particular reference to Italy, the regulatory framework regards the Legislative Decree n. 38/2005 and the Circular n. 262/2005 of the Bank of Italy, that provide detailed rules that must be followed by Italian banks in order to prepare their financial statements.Footnote 3 These rules are consistent with the IAS/IFRS (international accounting principles). Banks disclose several measurements of risk and useful pieces of information about credit risk in their financial statements, and particularly in the Notes, that integrate and complete a bank’s statement of financial position and profit and loss statement. The most valuable pieces of information on credit risk are disclosed in the following parts: part “A” (accounting policy), part “B” (information on balance sheet), part “C” (information on income statement), and part “E” (information on banking risks). In particular, part “E” provides information concerning different risk categories, methodologies, and models used to measure banks’ risk exposures, hedging practices, and so on.

Briefly, even in light of such recent changes, the legal framework governing risk reporting in banking is extremely fragmented. In the next section we describe the research design of the empirical study.

3 Methodology and Research Design

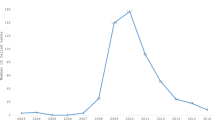

The purpose of this section is to analyze the methodology we employ to investigate credit risk disclosure practices in banking. The sample of this research consists of the ten largest Italian banks based on the book value of total assets, and the time horizon runs from 2012 to 2017 (Table 10.1).Footnote 4

Data collection derives from the analysis and evaluation of the three aforementioned most important risk disclosure reports: the Notes and the Management Commentary of the Annual Report and the Basel Capital Accord’s Pillar 3 report. We downloaded them from the banks’ official websites. As a whole, we read and analyzed 31,780 pages of disclosure reports from 2012 to 2017 (Table 10.2).

Data were collected through the application of content analysis on the annual balance sheets and Pillar 3 reports of the banks in the sample. A scoring model based on analytical grids was used.Footnote 5 The scoring model is divided into two parts. The first part is based on 30 credit risk disclosure indicators that are evaluated through the application of the following rule: score “1” if a bank discloses the information and score “0” if a bank does not disclose the information (Table 10.3). We identified the most relevant pieces of information that banks should include in their financial reports for credit risk disclosure purposes and we constructed the first part of the metric accordingly. In order to detect this kind of information, we adopted the following approach. First, we reviewed the scientific literature on banks’ risk reporting to identify all the crucial pieces of information that banks should disclose in their financial reports from a theoretical point of view. Second, we reviewed the risk reporting practices of the banks of the sample and chose the most useful pieces of information to be represented by a credit risk disclosure indicator. Furthermore, we carefully checked the regulatory requirements in terms of mandatory disclosure in order to be sure to not include any piece of mandatory information as a disclosure indicator in the first part of the metric. After this process, we identified 30 disclosure indicators for the first part of the scoring rule. These disclosure indicators are indexes that show the presence or the absence of the information described by the name/description of the indicator itself.

The second part of the scoring model is based on a judgment approach that takes into account 47 key disclosure parameters (Table 10.4). As shown in Table 10.4, these parameters are grouped into the following 11 subcategories: key aspects of credit risk management in banking, credit risk management decision disclosure, credit risk components, information on credit risk exposures, loan losses and measurement models, credit risk mitigation/transfer instruments, other key elements of bank credit risk, bank loan portfolio disclosure, credit rating disclosure issues, bank credit risk capital requirements disclosure, and general credit risk disclosure issues.

We assign a score from “0” to “5” after taking into account the following qualitative features of the disclosure: understandability, relevance, comparability, and reliability. These qualitative characteristics are outlined in the Conceptual Framework for IAS/IFRS by the International Accounting Standard Board (2010). Score “0” means that we find a severe lack of information disclosure; score “5” means that we find an excellent information disclosure. We assume that these qualitative features are extremely important for credit risk reporting purposes.

The process we adopted to identify these key disclosure parameters is similar to the one adopted for the first section of our metric. Thus, both the disclosure parameters and the subcategories were identified looking at the scientific literature, the risk reporting practices of the banks of the sample, and the regulatory requirements. As a result, we identified the information that banks should disclose from a theoretical and practical viewpoint. The decision of splitting each subcategory into different disclosure parameters relies on the willingness of making our evaluation as verifiable and as objective as possible, even though it is impossible to eliminate totally the subjectivity. After this process, we identified 11 subcategories/sections that include 3 to 6 key disclosure parameters.

With reference to the first part of the scoring model, the maximum score a bank can obtain is 30. As for the second part of the scoring model, the maximum score is 235. We assigned equal weight to each section of the first and second part of the scoring model because we assume that each section is equally important in determining the quality of banks’ risk disclosure. Lastly, we rescaled the summed scores in order to express the final score (disclosure quality index) on a 0–100-point scale. These normalized scores equate raw scoring gathered through different measurement techniques. A more detailed discussion of the research findings is provided in the section which follows.

4 Research Findings: Discussion

The following subsections focus on the results of this empirical study. As stated previously, the overall objective of this work was to connect qualitative and quantitative data through a scoring model in order to assess credit risk disclosure in banking institutions, add new academic insights, and provide practical implications. Details of the research findings from each bank in the sample will be presented in the subsections that follow.

4.1 Unicredit

Unicredit risk reporting shows a significant information overlap between Notes to the account and Pillar 3 disclosure report. The Management Commentary of the annual report does not contain any additional information on credit risk, and it attenuates the provision of an integrated perspective on bank credit risk. There is also a better balance between backward-looking and forward-looking information on credit risk in comparison to market risk (Scannella 2018; Scannella and Polizzi 2018).

In particular, in 2012, Unicredit provided a useful glossary and explanation of credit risk determinants. The qualitative description of credit risk mitigation techniques is informative enough, as well as the distinction between expected and actual credit losses. A detailed description of stress tests is provided in both Notes to the account and Pillar 3 report. The Notes to the account also provide a measure of Rarorac (risk-adjusted return on risk-adjusted capital) and the Management Commentary shows two balance sheet ratios with reference to credit risk without providing any comments. Moreover, there are few pieces of information on internal credit rating in comparison to 2016 risk reporting.

The disclosure on insolvency risk is better than other risk components. There are useful comparisons between internal and external credit ratings. The disclosure on personal guarantees and insurance contracts is not informative enough and mainly description-based. In contrast, the disclosure on credit derivatives is better from the quantitative instead of the qualitative point of view. In a wider perspective, the disclosure on unexpected losses is better than the disclosure on expected losses.

There are no explanations of methodologies that are used for loan loss provisioning. The rating assignment and rating validation (both internal and external) disclosures are quite informative and mainly descriptive. Both the Notes and the Pillar 3 report provide a high level of detail on measurement models for credit risk capital requirement and capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective). The disclosure on the economic capital is less informative than the regulatory capital. However, the methodologies that are used to evaluate the economic capital and its role in credit risk management are described appropriately.

In 2013, Unicredit’s credit risk disclosure did not show relevant improvements in comparison to the previous year. In brief, there is just a higher level of details with reference to EAD and recovery risk, mainly in the Pillar 3 report. The disclosure on model risk is much better, but still not satisfactory. The information on nonperforming loans improved in the Notes due to the implementation of the EBA’s Technical Standards in October 2013.

In 2014, credit risk disclosure was similar to the previous year. The disclosure on recovery risk and credit risk expected loss improved slightly, mainly in the Pillar 3 report. It is curious to mention that in the glossary the definition of “risk-weighted assets” is omitted.

In 2015, credit risk disclosure was almost identical to that of the previous year. There were just more details on nonperforming exposures, and the definition of “risk-weighted assets” is included in the glossary.

Credit risk disclosure in 2016 was characterized by some improvements in comparison to the previous year, particularly with reference to loan securitization, management of nonperforming loans, governance structure of the credit risk management, regulatory capital requirements, assignment and validation of bank credit rating systems, and complementarity and coherence of the Annual report and Pillar 3 report. In brief, the glossary provides comprehensible definitions of the most important aspects/terms of credit risk. Information on stress test is provided both in the Notes and the Pillar 3 report: mainly qualitative and descriptive in the Notes and analytical and quantitative in the Pillar 3 report. The results of the stress test are reported without an adequate level of details. In the Pillar 3 report the distinction between expected and actual credit losses is quite informative.

The disclosure on current and potential on-balance sheet exposures is better than the one related to off-balance sheet exposures. At the same time, the disclosure on unexpected credit losses is more informative than the one related to expected credit losses. In addition, the disclosure on model risk is not satisfactory and only qualitative and descriptive.

With reference to recovery risk, the disclosure is not satisfactory. The information on personal guarantees is scarce, as well as the information on insurance contracts on credit risk and credit derivatives. Unicredit provides useful information on internal economic capital (in 2016 Unicredit introduced the migration risk as a component of the economic capital), although it contains fewer details in comparison to the disclosure on regulatory capital. In the Pillar 3 report there are some pieces of information on specialized lending and it provides more details on regulatory capital in comparison to the Notes.

In brief, in 2016, there was still an information overlap between the Notes and the Pillar 3 report (e.g. expected credit risk losses, credit risk provisioning, etc.) and a good balance between backward and forward-looking information on credit risk (e.g. lifetime expected losses techniques, calculation of probabilities of default, use of migration matrixes, etc.). This balance is much better than Unicredit market risk disclosure (Scannella 2018). In addition, the Management Commentary does not provide any relevant information on credit risk in banking.

In 2017, credit risk reporting improved in various aspects, mainly in the Pillar 3 report, with the introduction of new tables and the provision of new pieces of information. In detail, the Pillar 3 report provides more information on back-testing PD for exposure classes and recovery risk, which increases the disclosure on the accuracy of potential credit risk exposures assessment, the accuracy of internal credit rating models, and the explanation of credit risk measurements. In addition, disclosure improvements have been made with reference to the analysis of nonperforming loans, credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet), and credit derivatives (with the introduction of the section “EU CR7: IRB method. Effects on RWA of credit derivatives that are used to hedge credit risk”). Lastly, some useful tables on current credit risk exposures (on- and off-balance sheet) are missing in the Pillar 3 report; the Management Commentary does not provide any relevant information on credit risk in banking. The information overlap between Notes to the account and Pillar 3 report attenuates the provision of an integrated view on bank credit risk.

4.2 Intesa Sanpaolo

Intesa Sanpaolo’s credit risk reporting shows higher forward-looking information and an integrated perspective in comparison to Unicredit credit risk reporting. Pillar 3 disclosure report provides information that is not disclosed in the Notes; the Management Commentary sheds some light on bank risk and provides cross-references to the Pillar 3 disclosure report and the Notes.

In particular, in 2012 Intesa Sanpaolo provided a useful glossary in the Pillar 3 report to easily understand key terms in credit risk reporting. The disclosure on stress test is mainly qualitative; it does not provide any details on future scenarios or their impacts on the economics and management of the bank. There are just few and low informative pieces of information on scenario analysis only in the Pillar 3 report.

The Management Commentary focuses mainly on the macroeconomic context and provides an integrated perspective on some critical aspects of bank risk, with particular reference to credit risk in banking, such as qualitative and quantitative analyses of loan portfolios, information on sovereign credit risk exposures and regulatory capital, and so on. Even though on this aspect the Management Commentary is better than Unicredit, the section “the expected development of the bank management” could be improved.

Disclosure on rating assignment and validation is slightly better than Unicredit. It is useful the table that compares internal rating classes and external agency rating classes as well as are the paragraph that analyses credit risk migration techniques and the description of the limitations of unexpected loan loss calculation. The methods of credit risk rating assessment are explained appropriately.

Credit risk disclosure provides useful information on potential exposures, with reference to categories of exposures and their maturities. The disclosure on bank loan portfolio concentration provides some useful details, mainly qualitative, but ultimately it is not satisfactory enough.

Loan securitization operations are well analyzed and reported. The disclosure provides information on the most important aspects of loan securitization operations that are performed by Intesa Sanpaolo. It provides an integrated and comprehensible view of bank loan securitization, although Unicredit seeks to delve deeper into the topic. It is probably related to the fact that Unicredit manages more loan securitization operations than Intesa Sanpaolo does.

In credit risk disclosure, the composition of the regulatory capital is well described and detailed. It also provides a good analysis of nonperforming exposures and credit risk provisioning methodologies. In addition, it provides information on specialized lending and its rating assessment methods, although some key details on the current credit risk of specialized exposures are not disclosed.

The information on off-balance sheet exposures seems slightly better than Unicredit. For example, the off-balance sheet exposure rating is well explained, and there are tables that support qualitative and descriptive analyses. In addition, the information gap between current and potential credit risk exposures is less evident than the one of Unicredit.

The disclosure on credit derivatives is strictly compliant with the Circular n. 262 of Bank of Italy (2005). An additional piece of information is provided in the Pillar 3 report which discloses the creditworthiness of credit derivative counterparties. With reference to personal guarantees, the disclosure is better than the one of Unicredit, mainly in the Pillar 3 report (e.g. types of guarantors, types of guarantor rating classes, etc.). In addition, the disclosure on collaterals and model risks seems more detailed than the one of Unicredit.

The disclosure on the bank economic capital for credit risk, within a managerial perspective, is slightly less detailed than the one of Unicredit, but it is quite effective and easy to understand.

Generally speaking, Intesa Sanpaolo risk disclosure does not provide enough tables and graphs that could primarily summarize descriptive information on credit risk. Consequently, it affects the comprehensibility of risk disclosure documents. However, a forward-looking perspective reflects an important focus on future credit risk exposures.

In 2013, there were no significant improvements in credit risk disclosure. It seems the same as the previous year. In particular, in the Notes and the Pillar 3 report, the risk appetite framework and the credit risk management strategies and policies are described better than in the ones of the previous year. The information on the economic capital in the Notes is slightly improved (e.g. economic capital absorption for types of business units). The content of the Management Commentary is similar to that of the previous year.

In 2014, credit risk disclosure was also similar to the one of the previous year. There were no relevant improvements. With reference to stress test results, they added a new paragraph “Comprehensive Assessment of the European Central Bank” in the Management Commentary. The lack of a summary table does not help the reader to obtain a quick view of it. In addition, it is curious to mention that credit risk reporting discloses the key term “unexpected loss” inside inverted commas, and it is used only twice in the Notes and seven times in the Pillar 3 report (it does not provide any definition of unexpected loss).

In 2015, Intesa Sanpaolo did not provide a higher level of credit risk disclosure in comparison to the previous year. It is important to notice a slight improvement in the description of nonperforming exposures, as well as expected credit risk losses. Even though in 2015 the forward-looking information is slightly improved, the lack of stress test results affects the final score of section M of the scoring model.

In 2016, Intesa Sanpaolo credit risk disclosure showed some improvements, particularly with reference to economic capital (e.g. the use of internal stress tests to evaluate the adequateness of economic capital), current off-balance sheet credit risk exposures, credit risk provisioning, and nonperforming loans. In addition, in the Pillar 3 report, there was a useful comparison between internal approach-based probabilities of default and actual default rates by types of economic sectors. Forward-looking information improved with reference to IFRS 9 and its future impacts on the bank balance sheet (e.g. lifetime probability of default and underlying methodologies). In 2016, there were more pieces of information on stress test results in comparison to the previous year. The Notes also provide a glossary. The same credit risk ratios are disclosed in the Pillar 3 report and Management Commentary. Finally, it is curious to mention that the information on specialized lending has diminished both in the Pillar 3 report and Notes.

In 2017, Intesa Sanpaolo credit risk disclosure showed almost the same improvements we noticed in Unicredit mainly because of the recently expanded risk disclosure requirements of the Pillar 3 report (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2017). In addition, Intesa Sanpaolo improved the disclosure on the expected qualitative and quantitative effects of the new IFRS 9 on the bank balance sheet. They provide more details on expected credit losses that help to better understand measurement models for expected losses and loan loss provisioning. We also found more information on credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet), credit risk aggregation and methodologies, and credit derivatives, with positive effects on the accuracy of both internal credit rating models and potential credit risk exposures assessment. Lastly, it slightly improved the disclosure on the explanation of credit risk management goals, procedures, processes, and policies, as well as the disclosure on nonperforming loan securitization.

4.3 Monte dei Paschi di Siena

In 2012, Monte dei Paschi risk disclosure showed a prominent backward-looking perspective instead of a forward-looking one on credit risk, primarily because of the low level of information on potential credit risk exposures, stress tests, scenario analysis, sensitivity analysis, and so on. With reference to the provision of an integrated perspective on bank credit risk, we noticed that Pillar 3 report provides some additional information than the Notes do, and the Management Commentary is a useful document for the bank risk reporting, providing a unified view on some crucial aspects of credit risk in banking (with useful tables and graphs).

In comparison to Unicredit, Monte dei Paschi discloses less information on capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective), measurement models for credit risk capital requirements, credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet), implications of internal credit rating for the bank management, and accuracy of internal credit rating models. In particular, for the rating assignment, they do not disclose properly the models adopted, and for the rating quantification, there are no comparisons among internal rating classes. In contrast, they provide more details on internal and external rating validation. There is not enough information on the comparison between internal and external credit ratings, as well as on credit risk aggregation and methodologies.

With reference to the analysis of the loan portfolio, we noticed that there is no information on loan portfolio correlation; the degree of loan portfolio concentration is explained better than Unicredit, and there is less information on loan portfolio composition in comparison to Unicredit. The useful table with the loan portfolio composition in terms of residual maturity is not disclosed because they perform a sensitivity interest rate risk analysis on the basis of internal models. However, this sensitivity analysis is not informative enough for credit risk. In general, there are fewer details and comments than Unicredit.

The disclosure on loan losses provisioning is affected by the low information level on accounting policies. In addition, the Pillar 3 report is not helpful on this topic. In contrast, the analysis of nonperforming loans is better than the one of Unicredit. The disclosure on nonperforming loans has a good level of details (e.g. balance sheet ratios, coverage ratios of nonperforming exposures, etc.). There are different tables and comments on the topic in all risk reporting documents.

With reference to loan securitization and its impacts on the economics and management of the bank, there are fewer details than Unicredit risk reporting. There is no information on special purpose vehicles and synthetic loan securitization. On this topic, the contribution of the Pillar 3 report is really important.

The information on measurement models for expected and unexpected credit losses is quite good. The disclosure on expected credit losses is detailed, comprehensible, and supported by a certain number of useful graphs and tables. The disclosure on unexpected credit losses is strictly connected to the disclosure on the bank economic capital. There are no details on model risk. It is worthwhile to notice that although they disclose some useful details on expected credit losses, they do not provide their total amount.

Monte dei Paschi does not provide a satisfactory disclosure on potential credit risk exposures (both on- and off-balance sheet), the accuracy of potential credit risk exposures assessment, recovery risk, credit risk elimination and avoidance, migration risk, credit risk mitigation techniques, and back-testing. The information on credit risk assumption, retention, and prevention is worse than Unicredit. The information on credit risk protection is slightly better (in particular in the Pillar 3 report).

With reference to the key aspects of credit risk management in banking, we noticed that Monte dei Paschi provides more information on the organizational aspects of credit risk management instead of credit risk strategies and policies.

The disclosure on risk tolerance is almost identical in the Notes and the Pillar 3 report. Nevertheless, in general, the information overlap between those risk reporting documents seems less significant than Unicredit.

Some internal scenario analyses are disclosed, mainly in the Pillar 3 report, with their implications in terms of credit risk, derivatives, and bank performances. Monte dei Paschi mentions the use of risk-adjusted performance indicators for internal risk management purposes, but it does not disclose any measure or type of such indicators.

The disclosure on stress test is scarce and mainly descriptive. There are just few details on stress test results and comments. The Pillar 3 report provides further information, but it is not relevant. In general, the forward-looking perspective suffers from a low level of detail, which does not help the reader to obtain a clear and adequate view on credit risk in banking.

It is important to highlight that, on the one hand, the disclosure on internal economic capital and unexpected credit loss is better than Unicredit and the comprehensibility is very good. On the other hand, the disclosure on regulatory capital and credit risk-weighted assets is less informative than Unicredit.

Generally speaking, we noticed that the distribution of information among risk reporting documents is different in comparison to Unicredit and Intesa Sanpaolo. Some aspects are well disclosed, while others are not disclosed at all. It is worthwhile to mention that in many parts of the annual report there are a lot of references to section “E” of the Notes, even though in this case the Pillar 3 report is an important document for credit risk disclosure. It also provides a useful glossary.

In 2013, Monte dei Paschi risk disclosure showed some improvements, with particular reference to the explanation of credit risk management goals, procedures, processes, and policies; credit risk assumption and retention; credit risk elimination and avoidance; accuracy of potential credit risk exposures assessment (because of more details on the back-testing mainly); personal guarantees; and accuracy of internal credit rating models. In the Management Commentary they introduced a new table “risk weighted assets—RWA” that shows also credit risk-weighted assets. With reference to the amount of unexpected loan loss, there are fewer details on the bank economic capital than the previous year. The disclosure on stress tests improved, but their results are missing.

In 2014, Monte dei Paschi credit risk disclosure showed some improvements. Briefly, we mention the following: in the Pillar 3 report, there are more pieces of information on expected and actual credit losses, rating back-testing, and a comparison between internal estimates of probabilities of default and actual defaults for rating classes; new sections of the Pillar 3 report on credit risk management policies and goals, the use of internal ratings for credit risk, and credit risk-weighted assets. It slightly improved the disclosure on stress tests in the Management Commentary and on bank capital adequacy for credit risk, mainly because of the introduction of a new section on bank regulatory capital in the Pillar 3 report. The geographical distribution of both on- and off-balance sheet exposures, that provided details on nonperforming exposures, is not disclosed anymore. In conclusion, the forward-looking information is slightly improved in comparison to the previous year, mainly because of a higher level of information on recovery risk and stress test.

In 2015, we noticed that the quality of credit risk disclosure was slightly reduced, mainly in the Notes. They provided fewer tables and graphs on internal economic capital and expected credit loss, as well as less information on current credit risk exposures (on-balance sheet), regulatory capital, and stress tests. In contrast, other parts of the risk disclosure showed some improvements, such as more pieces of information on measurement models for credit risk capital requirements, credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet), rating validation, recovery risk, and specialized lending. The disclosure on internal/external credit rating and credit derivatives showed slight improvements in the Pillar 3 report in comparison to the previous year.

In 2016, Monte dei Paschi improved the quality of its credit risk disclosure. It provided more details on credit risk prevention and protection, insolvency risk, collaterals (mainly in the Management Commentary), and personal guarantees (mainly in the Pillar 3 report, with the introduction of two new paragraphs on this topic). The disclosure on loan loss provisioning and insolvency risk was positively affected by the presence of some references to the new IFRS 9 and its impacts on migration risk, potential credit risk exposures, and potential bank risks. The disclosure on stress tests improved, as well as on credit risk balance sheet ratios, with the introduction of new ratios on the quality of bank loans.

In 2017, Monte dei Paschi credit risk disclosure showed almost the same improvements we noticed in Unicredit and Intesa Sanpaolo, mainly because of the recently expanded risk disclosure requirements of Pillar 3 report (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2017). In addition, we noticed some other disclosure improvements with reference to implications of internal credit rating for bank management, analysis of nonperforming loans, loan securitization, provisioning for loan losses, credit risk prevention and protection (it is worthwhile to mention the creation of a new “chief lending officer” that should improve the early detection of bank credit risk), accuracy of internal credit rating models, and potential credit risk exposures assessment. In 2017, the disclosure on stress test and potential credit risk exposures has been slightly reduced (on-balance sheet). Lastly, Monte dei Paschi partially adopted the new IFRS 9 in 2017 financial statement.

4.4 Banco Popolare and Banco BPM

Banco Popolare credit risk reporting shows a higher backward-looking than a forward-looking disclosure and an acceptable integrated perspective. The Pillar 3 disclosure report and the Notes are complementary documents, and the Management Commentary is useful for credit risk reporting purposes. In a wider perspective, credit risk reporting adopts a more narrative and qualitative approach instead of a quantitative one.

On closer inspection, in 2012, the explanation of credit risk management goals, procedures, processes, and policies is quite informative, although it contains fewer details than Unicredit. The Pillar 3 disclosure report provides a useful glossary to support the comprehension of some key credit risk dimensions. In addition, the definition of credit risk in the Pillar 3 disclosure report is quite precise and detailed.

With reference to credit rating disclosure issues, we noticed that the disclosure on internal rating, the comparison between internal and external rating, and the implications of internal credit rating for bank management is quite good, but there are not so many pieces of information on the accuracy of internal credit rating models. However, the existence of a good comparison between expected credit losses and actual credit losses supports the same score we assigned to Unicredit.

The disclosure on capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective), credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet), and measurement models for credit risk capital requirements is less informative than Unicredit. It also provides few tables and summaries. Although there are pieces of information on potential exposures, they are mainly related to the trading portfolio. Banco Popolare pays more attention to the regulatory perspective of capital requirements disclosure than internal and managerial perspective. Stress test results are provided only with reference to regulatory capital. The disclosure on sovereign risk is quite informative.

The Management Commentary provides two useful sections for credit risk reporting: analysis of results in a perspective view and risk management. They also provide a good synthesis of some important credit risk aspects. Other sections of the Management Commentary do not shed additional light on credit risk.

Different sections of credit risk reporting show a less informative disclosure in comparison to Unicredit: insolvency risk, current credit risk exposures (off-balance sheet), measurement models for unexpected loss, loan loss provisioning, analysis of nonperforming loans, and rating assignment. Although the information on loan securitization is less detailed than Unicredit, the Notes provide informative sections on risks and securitization (e.g. rating downgrading paragraph). The disclosure on loan portfolio correlation is not adequate, but Banco Popolare shows more information than other banks. The disclosure on loan portfolio concentration is characterized by the presence of a table and a narrative structure of the analysis of large risk exposures. The disclosure on credit risk aggregation and methodologies is quite qualitative, and the overview is not clear.

In 2013, Banco Popolare credit risk disclosure showed some improvements, with particular reference to rating validation; capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective); explanation of credit risk measurements; information on credit risk assumption and retention; and recovery risk. The information on stress test results is not provided. The increased volume of the risk disclosure in 2013 is mainly related to the merger by the incorporation of “Credito Bergamasco S.p.A.” into Banco Popolare.

In 2014, we noticed some improvements in Banco Popolare credit risk disclosure, with reference to explanation of credit risk management strategies, goals, procedures, processes, and policies; capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective); economic capital for credit risk (internal and managerial perspective); information on specialized lending; information on internal/external credit rating; and balance sheet ratios for credit risk. In 2014, the Management Commentary provided stress test results and more information on loan loss provisioning and nonperforming loans.

In 2015, Banco Popolare credit risk disclosure was almost the same as the previous year. We noticed some improvements with reference to accuracy of internal credit rating models (there are some details on back-testing, mainly for market risk rather than credit risk); credit risk elimination and avoidance (mainly in the accounting policy section); recovery risk and credit risk expected loss (with the introduction of new tables and qualitative information); and loan securitization. In contrast, the disclosure is slightly worse with reference to stress test results.

In 2016, better disclosure of the accounting policy (with reference to the introduction and implementation of the new IFRS 9) and stress test results (Pillar 3 disclosure report and Management Commentary) increased a forward-looking perspective on bank credit risk. We also noticed some disclosure improvements with reference to credit risk transfer (more information on nonperforming loan transferring in the Notes), insolvency risk (more information on the probability of default and loss given default), loan loss provisioning, and potential credit risk exposures (on-balance sheet).

On 1 January 2017, Banco Popolare and Banca Popolare di Milano merged to become Banco BPM Group. Thus, for 2017 we take into account Banco BPM credit risk reporting. In 2017, the quality of credit risk disclosure improved quite a lot with reference to disclosure reports. The structure of Banco BPM credit risk disclosure is similar to the previous Banco Popolare credit risk disclosure. Some disclosure improvements could be affected by the merger of the previous two banks into the new group.

Briefly, we mention the following disclosure improvements: loan loss provisioning and expected credit loss (mainly in the Notes); accuracy of internal credit rating models (more information on back-testing of rating systems in the Notes); credit risk-weighted assets, both on- and off-balance sheet (it is worthwhile to notice the introduction in the Notes of two useful tables: EU CR8—risk-weighted assets variations, and EU CR4—standardized method—credit risk exposures); capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective); current credit risk exposures (off-balance sheet); insolvency risk (to notice the introduction of a new table EU CR6—IRB method); measurement models for expected loss; model risk; unexpected loan loss; and economic capital for credit risk (the Pillar 3 disclosure report provides information on the risk appetite framework). The Management Commentary provides some information on nonperforming loans. Stress test results are not disclosed. Information on scenario analysis is provided only in the Notes. In short, backward-looking information on bank credit risk improved with reference to all credit risk reports.

4.5 UBI Banca

In 2012, UBI Banca credit risk reporting was characterized by a much more backward-looking perspective instead of a forward-looking one. With reference to the provision of an integrated perspective on bank credit risk, there are some information overlaps between the Notes and the Pillar 3 disclosure report. The Management Commentary provides useful information on credit risk, mainly qualitative, and supports the provision of an integrated view.

With reference to key aspects of credit risk management in banking (explanation of risk management goals, procedures, processes, policies; credit risk measurements; credit risk control systems), we observed a good level of disclosure. In comparison to Unicredit, it seems that the information in the Notes is much more qualitative than quantitative. A glossary is not provided.

In all credit risk reports, the disclosure on credit risk expected loss and unexpected loss is not adequate. It is not clear how the bank calculates them and their meaning. There is no explanation on credit risk components and risk-weighted assets. It affects negatively the understandability of credit risk disclosure. The information on value at risk and back-testing is mainly on market risk instead of credit risk. The analysis of nonperforming loans is quite good: in the Notes there are more details than Unicredit.

UBI Banca risk reporting provides some useful balance sheet ratios on credit risk with reference to each bank in the group. In contrast, an insufficient level of information is provided with reference to credit risk potential exposures, explanation of unexpected loan loss models used, explanation of credit risk-weighted assets calculation, credit risk aggregation and methodologies, internal/external credit rating, implications of internal credit rating for bank management, credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet), measurement models for credit risk capital requirements, and capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective). Information on stress test results on trading and banking book and scenario analysis is also provided. With reference to bank credit risk capital requirements disclosure, we noticed an evident gap between the regulatory and the internal/managerial perspective.

The disclosure on loan portfolio concentration and credit risk elimination/avoidance is slightly better than Unicredit; the Notes provide details on large credit risk exposures. In contrast, the disclosure on insolvency risk, migration risk, and recovery risk is worse than the one provided by Unicredit. In general, the disclosure on the current credit risk exposures (on-balance sheet) is better than the disclosure on potential credit risk exposures (on- and off-balance sheet), both qualitative and quantitative.

Credit risk disclosure does not provide an adequate level of information to evaluate the accuracy of potential credit risk exposures assessment and measurement models for unexpected losses. The disclosure on measurement models for expected losses, collateral, and personal guarantees is slightly worse than Unicredit. The disclosure on loan securitization is adequate and almost similar to Banco Popolare in 2012.

Even though in 2013 the volume of all credit risk reports increased, there was no significant improvement in credit risk disclosure. It seems the same as the previous year. We noticed slight improvements with reference to credit risk prevention and protection, credit risk assumption and retention, measurement models for expected loss, internal/external credit rating, implications of internal credit rating for bank management, recovery risk, analysis of nonperforming loans, and credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet).

The volume of credit risk reporting increased also in 2014. The structure of the Pillar 3 disclosure report changed in comparison to that of the previous year and it attenuates the comparability over time. In the Pillar 3 report, the disclosure on credit risk concentration slightly improved: it provides a distinction between sector concentration risk and single name concentration risk. The information is only qualitative and not sufficient to increase the score.

We noticed a better disclosure in comparison to the previous year with reference to the following aspects: measurement models for credit risk capital requirements (in the Pillar 3 report there are more details on risk-weighted assets); insolvency risk (disaggregation of credit exposures with reference to their creditworthiness); and explanation of credit risk management goals, procedures, processes, and policies (both in the Notes and Pillar 3 report). In addition, the Pillar 3 disclosure report provides more information on credit risk prevention and protection, credit risk expected loss, collateral, loan securitization, and credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet).

In 2015, credit risk disclosure did not improve significantly. Credit risk reporting provided more details on capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective); explanation of credit risk measurements (mainly with reference to the future introduction of the new IFRS 9); model risk; migration risk; and current credit risk exposures (off-balance sheet).

In 2016, UBI Banca risk disclosure showed some improvements, with particular reference to current credit risk exposures (on-balance sheet), mainly in the Management Commentary; measurement models for credit risk capital requirements (it is worthwhile to notice the introduction of a new paragraph “EBA Transparency Exercise 2016” and “SREP 2016”, as well as more details on capital conservation buffer); loan loss provisioning (mainly with reference to nonperforming loans); credit risk expected loss; and internal/external credit rating (the implementation of the new IFRS 9 affects both aspects).

In 2017, UBI Banca credit risk disclosure showed several improvements, mainly because of the recently expanded risk disclosure requirements of the Pillar 3 report (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2017) and the implementation of the new IFRS 9. On closer inspection, we noticed a better disclosure with reference to the following aspects: measurement models for expected loss (that incorporate forward-looking scenarios); credit risk transfer; loan securitization; credit risk mitigation; credit derivatives (mainly Over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives); credit risk elimination and avoidance (mainly with reference to the derecognition of credits from the balance sheet); explanation of credit risk management strategies; rating assignment; implications of internal credit rating for bank management; migration risk; potential credit risk exposures (on-balance sheet), mainly because of the introduction of a new section (sensitivity analysis BCE) in the Management Commentary; explanation of credit risk control systems; credit risk prevention and protection; potential credit risk exposures (off-balance sheet); and specialized lending. In short, the forward-looking information on credit risk increased in 2017 because of the implementation of the new IFRS 9 that affects many aspects of credit risk disclosure.

4.6 Banca Nazionale del Lavoro

Banca Nazionale del Lavoro is under the control of BNP Paribas. For this reason, its Pillar 3 disclosure report consists of just few pages. More detailed Pillar 3 reports are published by the holding bank (BNP Paribas). In order to take into account the necessary information, we have also analyzed the BNP Paribas Pillar 3 disclosure report with particular reference to Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, but unfortunately, it was not always possible to isolate such pieces of information. In addition, BNP Paribas Pillar 3 disclosure report does not provide appreciable information with reference to our scoring model. This aspect has a relevant impact on the disclosure quality index of the scoring model. Overall, we noticed that the volume of all Banca Nazionale del Lavoro credit risk reports is less than the one of other banks in the sample. It could be an example of a strategic under-reporting of bank risk (Begley et al. 2017; Core 2001; Lev 1992).

In 2012, Banca Nazionale del Lavoro provided much more backward-looking information on bank credit risk than forward-looking information. It is characterized by fewer details, a lack of useful narrative explanations and qualitative information, a concise analysis of stress test results, scarce use of tables and graphs, a lack of a glossary, and use of value at risk measures almost exclusively for market risk instead of credit risk. Information on bank credit risk is mainly provided by the Notes. This may affect the provision of an integrated perspective on bank credit risk.

Credit risk reporting provides a vague disclosure on insolvency risk, accuracy of internal credit rating models (back-testing is mainly used for market risk), explanation of credit risk management strategies, explanation of credit risk measurements, credit risk assumption and retention, credit risk transfer, credit risk elimination and avoidance, migration risk, and credit risk prevention and protection. Disclosure on rating validation and credit risk control systems is quite good, as well as the description of risk management functions in banking.

Information on credit risk exposures is vague and not adequate to fully comprehend credit risk expected and unexpected losses, and measurement models for expected and unexpected losses. An inadequate level of information is evident with reference to off-balance sheet credit exposures.

With reference to credit risk mitigation/transfer instruments, the disclosure on personal guarantees and credit derivatives is not informative enough; it is satisfactory for collateral and adequate for loan securitization, although it offers less information than Unicredit.

Furthermore, the bank loan portfolio disclosure is not adequate to comprehend the bank loan portfolio correlation, concentration, and credit risk aggregation and methodologies. Just few details are mentioned on the analysis of nonperforming loans and provisioning for loan losses. Credit risk balance sheet ratios are disclosed only with reference to regulatory capital.

The disclosure on credit rating issues is also scarce, particularly with reference to the implications of internal credit rating for bank management, internal/external credit rating, and rating quantification. The disclosure on rating assignment is slightly better.

The bank credit risk capital requirements disclosure is better with reference to the regulatory perspective than the internal/managerial perspective. The information on measurement models for credit risk capital requirements is scarce, as well as the use of economic capital for internal purposes. The disclosure on credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet) is slightly better.

In 2013, we noticed some improvements. In comparison to the previous year, the volume of bank risk disclosure increased; however, it had no significant impact on the comprehension of credit risk. The Pillar 3 disclosure report contains the same tables as the previous year, but with more details and explanations on credit risk-weighted assets, capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective), and measurement models for credit risk capital requirements. The Notes provide more information on OTC credit derivatives and clearing houses (it positively affects the disclosure on credit risk transfer), provisioning for loan losses (with the introduction of the shortfall and a better explanation of expected credit loss), internal/external credit rating, accuracy of internal credit rating models (with reference to the back-testing procedures for the internal rating system), explanation of credit risk management strategies, and credit risk measurements. In 2013, there was no information on the economic capital for credit risk (internal and managerial perspective).

Since 2014, Banca Nazionale del Lavoro has started to publish one report which is called “Relazione finanziaria” that includes the Notes, the Management Commentary, and the Pillar 3 disclosure report. We noticed that the Pillar 3 disclosure report contains more qualitative and quantitative information than the previous year, particularly with reference to credit risk expected loss, rating validation, implications of internal credit rating for bank management, credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet), measurement models for credit risk capital requirements, and credit risk prevention and protection.

The disclosures on collateral, loan securitization, credit risk balance sheet ratios (in the Management Commentary we noticed a higher number of credit risk ratios), economic capital for credit risk (internal and managerial perspective), and loan portfolio concentration (with reference to large exposures) also slightly improved.

In 2015, we noticed a significant reduction in the risk reporting volume. However, the credit risk disclosure is almost the same as the previous year. The reduction of the number of pages of risk disclosure affects the provision of an integrated perspective on bank credit risk. They started providing information on the new IFRS 9; consequently, it improved the disclosure on loan loss provisioning.

In 2016, Banca Nazionale del Lavoro improved the quality of its credit risk disclosure. It provides more details on credit risk expected loss (in the Management Commentary there are more pieces of information on expected loss at maturity for performing loans), accuracy of internal credit rating models (in the Notes we have some references to back-testing on PD, LGD, and EAD), explanation of credit risk management strategies, credit risk elimination and avoidance, insolvency risk, and loan portfolio concentration. It slightly improved the forward-looking information on bank credit risk, mainly with reference to the Management Commentary and the implementation process of IFRS 9.

In 2017, we noticed a lot of improvements in all credit risk reports. The backward-looking information on bank credit risk improved, as well as the forward-looking information. In particular, we noticed a better disclosure with reference to the following aspects: analysis of nonperforming loans; impacts of the first-time adoption of the IFRS 9; capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective); current credit risk exposures (the Notes contain new tables that provide different disaggregation of credit risk exposures); insolvency risk (with more details on the default credit exposures); credit risk aggregation and methodologies; current credit risk exposures (off-balance sheet); recovery risk; measurement models for expected loss; explanation of expected loan loss models used; explanation of credit risk management goals, procedures, processes, and policies (the Pillar 3 disclosure report introduces a new paragraph on risk management); and explanation of credit risk measurements and rating quantification. In particular, in 2017, more balance sheet ratios on credit risk were disclosed and compared to average ratios of the banking system. A glossary is still missing.

4.7 Mediobanca

Mediobanca obtains the lowest credit risk disclosure score of the whole sample, even though it is characterized by the highest increase over the evaluation period. There is no glossary, the Pillar 3 disclosure report is only in English (the Italian version is not available on the website), and the Management Commentary is almost useless for credit risk disclosure. In 2012, Mediobanca had not adopted the internal rating models for regulatory purposes yet. Consequently, it affected the credit risk disclosure in many aspects (rating assignment, quantification, validation, and internal/external credit rating models).

The information on credit risk determinants is inadequate. The Pillar 3 disclosure report provides some brief useful pieces of information on credit risk concentrations in connection with credit risk mitigation techniques, capital adequacy, analysis of nonperforming loans, provisioning for loan losses, and explanation of credit risk mitigation/transfer instruments. The back-testing is applied only to value at risk for market risk and to hedging operations. The disclosure on credit risk management strategies, goals, procedures, processes, policies, credit risk measurements, and credit risk control systems is less informative than other banks in the sample. There are just few pieces of information with reference to credit risk assumption and retention, credit risk prevention and protection, credit risk elimination and avoidance, insolvency risk, migration risk, and recovery risk.

Mediobanca disclosure on credit risk exposures is almost similar to Banca Nazionale del Lavoro. The disclosure on loan losses and measurement models is affected by a low level of information, with the exception of measurement models for unexpected losses. The level of details on collateral, personal guarantees, credit derivatives, and loan portfolio concentration is similar to the credit risk reporting of Unicredit. The Pillar 3 disclosure report contains useful information on banking book securitization.

A low level of qualitative and quantitative information characterizes the loan portfolio composition, credit risk aggregation and methodologies, credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet), measurement models for credit risk capital requirements, and capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective). There are just few balance sheet ratios on credit risk. There is no information on economic capital for credit risk. Notwithstanding the low quality of disclosure, credit risk reporting is quite easy to read (but there are neither tables nor graphs). Consequently, it affects the provision of an integrated perspective on bank credit risk.

In 2013, credit risk disclosure was the same as in the previous year. We just noticed a slight reduction in the number of pages and a slight improvement with reference to the explanation of credit risk management strategies (in the Management Commentary) and loan securitization.

In 2014, credit risk disclosure in the Pillar 3 report and Notes improved mainly with reference to explanation of credit risk measurements, credit risk expected loss, credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet), analysis of nonperforming loans, information on internal/external credit rating, rating assignment, and measurement models for credit risk capital requirements.

In 2015, Mediobanca improved significantly the quality of its credit risk disclosure. It provides more details on provisioning for loan losses, insolvency risk, recovery risk, credit risk measurements, credit risk assumption and retention, credit risk transfer and securitization, current credit risk exposures (on- and off-balance sheet), rating validation, and capital adequacy for credit risk (mainly in the Pillar 3 report). The volume of credit risk reporting increased a great deal.

In 2016, we noticed better forward-looking information on bank credit risk mainly because of the disclosure on stress test results and new accounting principle of the IFRS 9. The disclosure on IFRS 9 affects many improvements of credit risk reporting, such as provisioning for loan losses, measurement models for expected loss, potential credit risk exposures (on- and off-balance sheet), insolvency risk, and migration risk. We also noticed some other improvements with reference to the analysis of nonperforming loans; implications of internal credit rating for bank management; explanation of credit risk management goals, procedures, processes, and policies; and the use of risk-adjusted performance indicators (only for the management compensation policy). It is strange to notice that the definition of credit risk is missing in the Pillar 3 disclosure report. Similar to other banks in the sample, the denomination of “large risks” changed into “large exposures”.

In 2017, Mediobanca credit risk disclosure improved undoubtedly, both from the qualitative (with the introduction of a useful and well-structured glossary) and quantitative points of view (mainly backward-looking information on bank credit risk). In detail, we found better description and more data with reference to nonperforming loans; rating validation; accuracy of internal credit rating models; credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet); explanation of credit risk management strategies; explanation of credit risk management goals, procedures, processes, and policies; credit risk: expected loss; recovery risk; loan securitization; rating quantification; and capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective).

4.8 BPER Banca

BPER Banca credit risk reporting is characterized by a significant information overlap between the Pillar 3 disclosure report and the Notes. The Pillar 3 report provides few pieces of information in addition to the information provided by the Notes.

In 2012, credit risk disclosure is not adequate in all risk reports. It is worthwhile to notice that the Management Commentary provides a brief synthesis on banking risks and exposures that helps to provide an integrated perspective on bank credit risk. Like all other banks in the sample, backward-looking information on bank credit risk is better than forward-looking information.

We found a low level of qualitative and quantitative information with reference to the following credit risk aspects: explanation of expected loan loss models used, credit risk exposures, credit risk management decisions, credit risk components; loan losses and measurement models; credit risk mitigation/transfer instruments (with the exception of loan securitization); bank loan portfolio; model risk; collaterals; scenario analysis; and credit risk assumption, retention, prevention and protection. BPER Banca employs external rating systems, which affects the disclosure on credit rating. There is no information on stress tests, back-testing, and economic capital (internal and managerial perspective). A glossary is not provided and it negatively affects the first part of the disclosure scoring model.

In comparison to the previous year, in 2013, we noticed some slight improvements in credit risk disclosure. We found more qualitative and quantitative information with reference to analysis of nonperforming loans; explanation of credit risk control systems; credit risk assumption and retention; rating validation; balance sheet ratios on credit risk; and loan securitization (mainly in the Management Commentary).

In 2014, BPER Banca provided a better credit risk disclosure, particularly with reference to explanation of credit risk measurements; personal guarantees and collaterals; accuracy of potential credit risk exposures assessment; explanation of credit risk management strategies; current and potential credit risk exposures (on-balance sheet); credit risk assumption, retention, prevention, and protection; credit risk expected loss; specialized lending; insolvency risk; stress test results; and capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective). In addition, it is worthwhile to notice that the denomination of “large risks” changed into “large exposures”, and many sections of the Notes and Pillar 3 disclosure report are exactly the same.

In 2015, we noticed some improvements of backward-looking information on bank credit risk with reference to rating quantification, rating validation, rating assignment, recovery risk, loan portfolio concentration, measurement models for credit risk capital requirements, explanation of credit risk control systems, and balance sheet ratios on credit risk (they introduced two new risk ratios). The information on specialized lending is missing, and stress test results are moved to the Notes.

In 2016, the volume of the Pillar 3 disclosure report increased significantly. In this report, we found a better disclosure on the following aspects: credit risk management goals, procedures, processes, and policies; specialized lending; explanation of organizational issues related to the bank lending activity; implications of internal credit rating for bank management; internal/external credit rating; accuracy of internal credit rating models; measurement models for expected loss; explanation of credit risk measurements; credit risk elimination and avoidance; loan portfolio concentration. The analysis of potential impacts of the IFRS 9 in banking improved the disclosure on the following aspects: rating quantification; migration risk; insolvency risk; recovery risk; provisioning for loan losses. It contributes to enhancing a forward-looking perspective on bank credit risk. Some balance sheet ratios on credit risk are provided. In addition, in 2016, BPER Banca started employing the IRB methodology to calculate credit risk. It affected many aspects of credit risk disclosure.

Like the previous year, in 2017, we observed some important improvements in credit risk disclosure. The volume and complexity of credit risk reporting increased; however, it does not provide enough tables and graphs. It affects the integrated view on bank credit risk. In particular, we noticed disclosure improvements with reference to credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet); implications of internal credit rating for bank management; credit risk transfer and loan securitization; credit risk elimination and avoidance; and credit risk management goals, procedures, processes, and policies. In the Management Commentary, the information on economic capital for credit risk (internal and managerial perspective) is missing. In conclusion, the implementation process and a forward-looking approach of the IFRS 9 contributed to improving the disclosure of the aforementioned credit risk aspects. Although the quantitative disclosure on credit risk measurements needs to be improved, the qualitative disclosure on key aspects of credit risk management in banking is adequate and, in some aspects, better than other banks in the sample.

4.9 Banca Popolare di Milano

Banca Popolare di Milano credit risk reporting is characterized by a good balance between qualitative and quantitative information. In some aspects, it is better than other banks of similar dimensions in the sample. Credit risk disclosure is much more backward-looking than forward-looking. They put much more emphasis on forward-looking information on market risk instead of credit risk. We also noticed an information overlap between the Notes and the Pillar 3 disclosure report that affects the provision of an integrated perspective on bank credit risk. They provide a well-structured Management Commentary, but they need to exploit better its communication potentialities. The glossary in the Notes provides useful definitions that enhance the comprehensibility of credit risk reporting.

In 2012, it is worthwhile to highlight an adequate disclosure on the following credit risk aspects: explanation of credit risk management goals, procedures, processes, and policies; explanation of credit risk control systems; credit risk transfer and loan securitization; organizational structure of bank risk management; measurement models for credit risk capital requirements; capital adequacy for credit risk (regulatory perspective); personal guarantees and collateral, and recovery risk; and analysis of nonperforming loans.

Banca Popolare di Milano does not show a well-detailed disclosure with reference to credit risk-weighted assets (on- and off-balance sheet); back-testing (mainly on market risk); internal/external credit rating; scenario analysis and sensitivity analysis (mainly for market risk); credit risk assumption, retention, prevention, and protection; credit risk elimination and avoidance (it focuses on accounting issues); insolvency and migration risk; credit risk expected and unexpected loss; measurement models for expected and unexpected loss; credit derivatives; rating validation; implications of internal credit rating for bank management; and accuracy of internal credit rating models. Disclosure on credit risk exposures is better for current exposures than potential ones; it is also better for on-balance rather than off-balance sheet exposures. Loan portfolio concentration and provisioning for loan losses have a better disclosure in the Pillar 3 report than in the Notes.

In 2013, we noticed a significant increase in the number of pages of the bank’s risk reporting; however, many parts of credit risk reporting are exactly the same as the previous year. In 2013, slight improvements are related to the following aspects: explanation of credit risk measurements; credit risk prevention and protection; explanation of credit risk management strategies; accuracy of potential credit risk exposures assessment; description of model risk; risk-adjusted performance indicators (they provide the definition and value of the “risk-adjusted return on risk-adjusted capital”, which is known as Rarorac).