Abstract

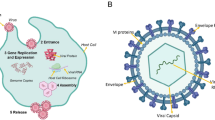

Virus particles, ‘virions’, range in size from nano-scale to micro-scale. They have many different shapes and are composed of proteins, sugars, nucleic acids, lipids, water and solutes. Virions are autonomous entities and affect all forms of life in a parasitic relationship. They infect prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. The physical properties of virions are tuned to the way they interact with cells. When virions interact with cells, they gain huge complexity and give rise to an infected cell, also known as ‘virus’. Virion–cell interactions entail the processes of entry, replication and assembly, as well as egress from the infected cell. Collectively, these steps can result in progeny virions, which is a productive infection, or in silencing of the virus, an abortive or latent infection. This book explores facets of the physical nature of virions and viruses and the impact of mechanical properties on infection processes at the cellular and subcellular levels.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Physics

- Cell biology

- Virus

- Virion

- Computational virology

- Modelling

- Tracking

- Trafficking

- Uncoating

- Genome release

- Reverse transcription

- Structural evolution

- Viral lineage

- Active matter

- Liquid unmixing

- Inclusion bodies

- Virion morphogenesis

- Maturation

- Mechanical properties

- Stiffness

- Pressure

- Water wire

- Acidic pH

- Alkaline pH

- Proton diode

- Anisotropic mechanics

1.1 Introduction

The chapters in this book are written by physicists, chemists, computational scientists and biologists. Joining forces across disciplines has been a long-standing and fruitful approach to advancing the life sciences and furthering understanding of infectious disease. For example, biology, chemistry and physics have debated about the nature and the general principles of living matter [1,2,3]. We now realize that important aspects of living matter are governed by self-organization of their components. This insight has been largely based on a combination of wet lab experimental biology and mathematical modelling merging concepts of discrete particle physics and fluid dynamics [4,5,6]. It has given rise to a field of ‘active matter’, which aims to assemble a theory of living matter in biology incorporating the rules of mechanics and statistics. Not surprisingly, viruses have been long known to use self-organizing processes to assemble virions from protein and nucleic acid building blocks produced in excess in the infected cell [7, 8].

Alone, viruses have other intriguing properties relating them to active matter. For example, they are a swarm of genetically related elements and give rise to a productive infection when thousands of particles enter an organism [9, 10]. How this relates to the fact that cellular life is based on self-propelled entities from which large-scale structures and movements arise has remained unknown. The question is critical, however, since viruses gain importance in an increasingly globalized world where they emerge and spread unpredictably between animals, humans and plants [11, 12]. Furthermore, increasingly powerful strategies are designed to engineer viruses for the treatment of disease by gene therapy approaches and antagonizing pathogenic bacteria in humans and livestock [13,14,15].

The book here brings together an interdisciplinary group of physicists, chemists, mathematicians and biologists and explores how the physical nature of virus particles impacts on virus infections. It covers a select range of viruses, including enveloped and non-enveloped viruses, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), rotavirus (RV), rabies virus (RABV), adenovirus (AdV) and the insect virus Triatoma virus (TrV).

1.2 Chapter 2: Virion Tracking in Entry

The chapter by Susan Daniel and Lakshmi Nathan describes some of the intricate pathways, by which virions enter into host cells [16]. The authors contrast single virus tracking experiments in cells and on biomimetic membranes assembled in vitro and discuss the pros and cons of both settings by highlighting examples of enveloped virus membrane fusion assays. They also discuss the power of high-resolution single virus experiments and put this in contrast to biochemical assays lacking spatial and temporal resolution at large but providing population average data.

1.3 Chapter 3: Uncoating of Rotavirus

Daniel Luque and Javier Rodriguez provide a comprehensive overview of the structural changes of the rotavirus (RV) particle in the course of entry into cells [17]. RV is a medium-sized 100 nm large, triple-layered non-enveloped particle with a segmented double-stranded (ds) RNA genome. The particle is primed for entry and uncoating by limited proteolysis during egress and release. It undergoes a series of remarkable conformational changes triggered by interactions with host cell receptors and ionic cues. These limited uncoating steps activate the membrane penetration machinery, leading to the disruption of the limiting endosomal membrane and release of the dsRNA segments into the cytosol. Intriguing questions arise, for example, whether the outer capsid protein VP7 serves as a quasi-enveloped fusion protein, or how the virion structures in high and low calcium ions inform about the disassembly mechanism in endosomes.

1.4 Chapter 4: Host Factors in HIV Capsid Interactions

Leo James provides an atomistic level view of the interactions of critical host factors with the incoming capsid of HIV during entry [18]. The author raises arguments to diffuse the long-held notion in the field that the capsid is dismantled soon after virion fusion with the plasma membrane or an endosomal non-acidified membrane. Rather, it is now emerging that the capsid serves as a shield to contain the viral genome during trafficking throughout the cytosol. It thereby acts akin to the capsids of icosahedral DNA viruses, such as AdV, herpes virus, parvovirus and hepatitis B virus, all of which contain their viral genome up to the critical uncoating step close to the site of viral replication (for reviews, see [19,20,21,22,23]). This similarity is reinforced by the notion that capsid interacts with a range of host factors. These views open ways towards designing new virus inhibitors targeting the interface between the virion and host factors in the cytosol, or triggering premature viral uncoating distant from the replication site. The chapter also describes exciting new insights into yet another fundamental question in lentivirus infection biology, namely how and where the reverse transcription of the positive sense RNA genome into DNA occurs. Analyses of the available structures of the HIV capsid and new structures of purified capsid protein hexamers revealed a cluster of positively charged arginine residues at the center of each hexamer, potentially providing hundreds of gatable portals, through which to recruit nucleotides into the lumen of the capsid [24]. The concept emerges that the capsids of all lentiviruses are functioning as a semipermeable reaction chamber for importing and consuming nucleotide triphosphates for reverse transcription of the viral genome. This would be reminiscent of bacterial microcompartments, which isolate toxic reaction products from the rest of the cytoplasm [25] and consume metabolites by sequestering appropriate enzymes into dedicated protein cages [26].

1.5 Chapter 5: Virus Structure, Lineage and Evolution

Nicola Abrescia and Hanna Oksanen delve into the nature and evolutionary lineages of membrane-bearing icosahedral viruses, inspired by studies on the PRD1 bacteriophage, a distant relative of AdV [27]. Membrane-bearing phages are different from eukaryotic enveloped viruses as they contain an internal rather than external membrane [28]. The authors discuss this feature. They also highlight the concept of ‘structural evolution’, which entails a relationship of structure to function across viral lineages spanning the three domains of life, notably in the absence of any discernable relationship in the sequence of the viral genomes [29]. This concept is also important for human viruses, for example the highly divergent picornaviruses, which comprise enteroviruses and respiratory viruses with common structural determinants, and mechanisms of membrane-bound replication [30, 31]. It is interesting to note that the structure of PRD1 is evolutionarily related to AdV [32]. This does not necessarily imply, however, that the two virions also function the same way in entry and assembly. For example, PRD1 is bearing a striking unique vertex, through which the viral genome is packaged and released in an ATP- and pressure-dependent manner, respectively [33]. In contrast, current evidence for AdV does not indicate a unique vertex in the icosahedral structure [34, 35]. This implies that AdV may not package its genome through a specialized vertex structure into a preformed capsid, unlike other eukaryotic DNA viruses, such as herpes simplex virus type 1 which bears a unique portal [36]. Rather, AdV may use a co-assembly process of capsomers and viral genome to give rise to virions [37]. In fact, the conditional genetic ablation of the DNA-organizing viral protein VII does not abrogate the formation of stable virions but gives rise to particles that are indistinguishable from wild type, except lacking protein VII, and some processing defects inside the capsid [38]. To our knowledge, there is no precedence for a viral DNA packaging machine that would accept both protein-bound and protein-free DNA. The evidence in case of AdV therefore strongly argues against a mechanism that packages viral DNA into a preformed virion but favors a model of co-packaging DNA and protein to form particles.

1.6 Chapter 6: Virus Assembly and Liquid Unmixed Compartments

In the next chapter, Jovan Nicolic, Danielle Blondel, Yves Gaudin and colleagues describe principles of particle assembly involving liquid–liquid phase separated, membrane-free compartments in the virus [39]. They elaborate on the structure and the function of viral assembly zones, often referred to as inclusion bodies. These liquid unmixed zones are considered as ‘active matter’, much like the nucleolus, stress granules or P-bodies, and contain intrinsically disordered proteins poised to interact with key proteins and RNAs to give rise to new virions. Viral factories formed by liquid–liquid phase separation ensure that the virus distinguishes self from non-self in the infected cell.

1.7 Chapter 7: Virus Maturation

Newly synthesized virions are often not readily infectious, unless they undergo a process called maturation, driven by limited proteolysis. Immature particles are protected against untimely uncoating cues in the assembly or egress pathways and traffic in a quasi-undisturbed manner through the cytosol or secretory pathways. Carmen San Martín describes how virion maturation entails conformational and structural changes to control the stability of the particle [40]. This is important because predominantly the mature virions are susceptible to cues from the host triggering productive virion entry into cells [41,42,43,44]. The author explores the biochemical process of virion maturation in icosahedral viruses from four lineages according to the structure of their capsid proteins (picornavirus-like, bluetonguevirus-like, HK97-like and PRD1-like), as well as alpha-, flavi- and retroviruses. San Martín further discusses how virion maturation changes the physical properties of particles and how this affects the response of the virions to uncoating cues.

1.8 Chapter 8: Mechanics of Virions

Mechanical properties of the virion determine both the strength and the unpacking mechanism of the viral genome. They represent key features of any infectious virus particle. Viral mechanics are dominated by the stiffness of the capsid shell, often in combination with the internal pressure from the tightly packed genome [45, 46], and can be tuned in the course of infectious entry into cells, for example by low pH, as shown for influenza A virus [47, 48]. Pedro de Pablo and Iwan Schaap explain how atomic force microscopy (AFM) helps to explore the surface topology and the mechanical properties of virions and how AFM identifies domains of the virion with distinct stiffness and particular susceptibility to cues from the host [49]. This is remarkable since virion stiffness has been shown to regulate the entry of immature HIV-1 particles [50]. Further to this, mechanical host cues occur on the AdV particles at the cell surface and catalyse a stepwise disassembly process of the virion. The process delivers leaky capsid shells containing the viral DNA to the cytosol, and the particles dock to nuclear pore complexes and deliver their DNA cargo into the nucleus upon rupture [20, 51,52,53]. At the stage of virion docking to the nuclear pore complex, the capsid is still pressurized by the entropic energy of the condensed viral genome, and this may impact on how the genome eventually transits through the nuclear pore complex into the nucleus upon the disassembly of the capsid [54,55,56]. This concept is built on prior studies with bacteriophage phi29 which showed that the pressure inside the virion is affected by DNA condensation, which was reversibly tuned by the DNA binding agent spermidine added to the virion in solution [57].

1.9 Chapter 9: Proton Diode and Alkaline pH in Insect Viruses

The chapter written by María Branda and Diego Guérin explores the physico-chemical mechanisms for proton conductance through protein cavities in the virion shell of the insect virus Triatoma virus (TrV) [58]. TrV is a picornavirus-like particle of the Dicistroviridae replicating in insects but not in humans. TrV is exposed to alkaline pH in the insect intestines, and excreted in large amounts in the insect feces, from where virions can be isolated and subjected to structural analyses. Such analyses showed that under extreme natural conditions, such as drying, the particles do not disintegrate but are held intact by the internal genome, which prevents capsid collapse [59]. In addition, the virion responds to changes in pH. Based on the atomic structure of TrV, quantum mechanics and molecular dynamic calculations, the authors put forward a model of water wires across the capsid shell at the fivefold axes of the icosahedral particles. In alkaline pH, this wire conducts protons from the inside of the virion to the outside. The wire is selective for protons due to a narrow restriction leading it to behave like a ‘proton diode’. Remarkably, the diode does not allow protons to enter the virion lumen, which is consistent with the notion that the TrV particles are stable at pH up to 3.5. The particles become unstable at alkaline pH, which extracts protons from the virions. The model indicates that proton efflux increases the negative charges on the proteins inside the virion. This in turn removes positive inorganic ions, such as magnesium ions, from the RNA genome, which leads to RNA decondensation, expansion and eventually release from the virion. The authors use their model to estimate that at pH 8.5, the export of protons increases the charge excess on RNA by about 16%. Concomitant with RNA release, the internal protein VP4 is extruded and becomes membrane disruptive in a dose-dependent manner. These events likely mimic the situation in the insect rectum, where the virion is exposed to alkaline pH. By this elaborate unidirectional machinery, the virion selectively responds to changes in the environment to execute the RNA uncoating process, yet remains stable in dry conditions. The chapter impressively illustrates the power of combined experimental and theoretical approaches in analysing structure–function relationship in virus particles under harsh chemical conditions. Remarkably, this contrasts other viruses that are exposed to less harsh chemical environments in their life cycle. For example, during entry and uncoating AdV breaks off entire penton capsomers at the fivefold axes, the weakest part of the virion [60,61,62,63]. This exposes the membrane lytic protein but leaves the virion DNA in the capsid shell, well protected from the DNA sensors in the cytoplasm [52, 64].

1.10 Chapter 10: Multilayered Computational Modelling of Viruses

The final chapter by Elisabeth Jefferys and Mark Sansom describes how computer simulations can guide the exploration of virion properties and virion interactions with host components [65]. Computational virology opens the field to predictions that go beyond the readily doable wet lab experiments but remain testable by empirical approaches. The authors delve into the detailed mapping of mechanical properties of single virions, including the behaviour of fusion peptides of enveloped viruses, modelling of viral capsid assembly and genome encapsidation over extended periods of time, and end up with a discussion of whole viral particle simulations. They conclude by providing a high-level view on the power of computational approaches in virology. Computational approaches allow asking questions, such as: is a protein in the virion envelope directly exposed to the environment, and hence a good drug target? Or what is the impact of N- and O-linked glycosylation on the antigenic variation in the ectodomain of viral envelope proteins, and how do they contribute to the shielding of the epitopes on the virion? Such questions are relevant for the identification of neutralizing anti-HIV antibodies or other molecules directed to the virion, a notoriously difficult task. Computational virology can also use information about protein–protein contacts from the crystal structures of icosahedral particles and simulate the mechanics of the capsids to predict anisotropic properties of the virion. Anisotropy in virion mechanics is increasingly recognized as a key property of virions to respond to chemical or mechanical cues from the cell during entry. Simulations of viral structures and dynamics have implications for cell biology and imaging, two distinct fields with increasing overlaps [22, 66, 67]. The approach outlined by Jefferys and Sansom also illustrates the power of simultaneously combining models at different resolutions to focus available computing power on specific components of interest, and deepen mechanistic insights into the biophysical and biochemical processes that enable infectious agents to usurp the functions of host cells and cause disease. Computational implementations of mathematical models will thereby enhance causal insights into virus infection biology.

1.11 Outlook

Physical virology has been pioneered in the phage community, enhanced by powerful genetics and biochemical approaches [68]. It has become an emerging field of interest for mammalian cell biology, medicine and nano-science, with an impact on disease mechanisms, precision medicine and controlled drug delivery [69, 70]. Nowadays, the power of physical virology is perhaps most impressive, when the physical nature of the particles is linked to dynamic changes in the virions during the entry, assembly and maturation processes of the particles in host cells. We are looking forward to new surprising and enriching interactions between virologists, physicists and computational scientists for further insights into the nature of infectious disease.

References

Beadle GW, Tatum EL (1941) Genetic control of biochemical reactions in Neurospora. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 27:499–506. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.27.11.499

Dronamraju KR (1999) Erwin Schrodinger and the origins of molecular biology. Genetics 153:1071–1076

Luria SE, Delbruck M (1943) Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics 28:491–511

Nedelec FJ, Surrey T, Maggs AC, Leibler S (1997) Self-organization of microtubules and motors. Nature 389:305–308. https://doi.org/10.1038/38532

Toner J, Tu Y (1995) Long-range order in a two-dimensional dynamical XY model: how birds fly together. Phys Rev Lett 75:4326–4329. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.4326

Vicsek T, Czirok A, Ben-Jacob E, Cohen II, Shochet O (1995) Novel type of phase transition in a system of self-driven particles. Phys Rev Lett 75:1226–1229. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.75.1226

Caspar DL, Klug A (1962) Physical principles in the construction of regular viruses. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 27:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1101/SQB.1962.027.001.005

Johnson JE, Speir JA (1997) Quasi-equivalent viruses: a paradigm for protein assemblies. J Mol Biol 269:665–675. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmbi.1997.1068

Domingo E, Sabo D, Taniguchi T, Weissmann C (1978) Nucleotide sequence heterogeneity of an RNA phage population. Cell 13:735–744. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(78)90223-4

Eigen M (1993) Viral quasispecies. Sci Am 269:42–49

Greber UF, Bartenschlager R (2017) An expanded view of viruses. FEMS Microbiol Rev 41:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuw044

Lederberg J (2000) Infectious history. Science 288:287–293. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.288.5464.287

Cisek AA, Dabrowska I, Gregorczyk KP, Wyzewski Z (2017) Phage therapy in bacterial infections treatment: one hundred years after the discovery of bacteriophages. Curr Microbiol 74:277–283. https://doi.org/0.1007/s00284-016-1166-x

Schmid M, Ernst P, Honegger A, Suomalainen M, Zimmermann M, Braun L, Stauffer S, Thom C, Dreier B, Eibauer M et al (2018) Adenoviral vector with shield and adapter increases tumor specificity and escapes liver and immune control. Nat Commun 9:450. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02707-6

Young R, Gill JJ (2015) Microbiology. Phage therapy redux – what is to be done? Science 350:1163–1164. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad6791

Nathan L, Daniel S (2019) Single virion tracking microscopy for the study of virus entry processes in live cells and biomimetic platforms. In: Greber UF (ed) Physical virology – virus structure and mechanics. Springer, Berlin

Rodríguez JM, Luque D (2019) Structural insights into rotavirus entry. In: Greber UF (ed) Physical virology – virus structure and mechanics. Springer, Berlin

James LC (2019) The HIV-1 capsid: more than just a delivery package. In: Greber UF (ed) Physical virology – virus structure and mechanics. Springer, Berlin

Fay N, Pante N (2015) Old foes, new understandings: nuclear entry of small non-enveloped DNA viruses. Curr Opin Virol 12:59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2015.03.017

Flatt JW, Greber UF (2017) Viral mechanisms for docking and delivering at nuclear pore complexes. Semin Cell Dev Biol 68:59–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.05.008

Radtke K, Dohner K, Sodeik B (2006) Viral interactions with the cytoskeleton: a Hitchhiker’s guide to the cell. Cell Microbiol 8:387–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00679.x

Wang IH, Burckhardt CJ, Yakimovich A, Greber UF (2018) Imaging, tracking and computational analyses of virus entry and egress with the cytoskeleton. Viruses 10(4):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10040166

Yamauchi Y, Greber UF (2016) Principles of virus uncoating: cues and the snooker ball. Traffic 17:569–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/tra.12387

Jacques DA, McEwan WA, Hilditch L, Price AJ, Towers GJ, James LC (2016) HIV-1 uses dynamic capsid pores to import nucleotides and fuel encapsidated DNA synthesis. Nature 536:349–353. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature19098

Tanaka S, Sawaya MR, Yeates TO (2010) Structure and mechanisms of a protein-based organelle in Escherichia coli. Science 327:81–84. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1179513

Chowdhury C, Chun S, Pang A, Sawaya MR, Sinha S, Yeates TO, Bobik TA (2015) Selective molecular transport through the protein shell of a bacterial microcompartment organelle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:2990–2995. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1423672112

Oksanen HM, Abrescia NGA (2019) Membrane-containing Icosahedral Bacteriophage PRD1: the dawn of viral lineages. In: Greber UF (ed) Physical virology – virus structure and mechanics. Springer, Berlin

Espejo RT, Canelo ES (1968) Properties of bacteriophage PM2: a lipid-containing bacterial virus. Virology 34:738–747. https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6822(68)90094-9

Bamford DH, Burnett RM, Stuart DI (2002) Evolution of viral structure. Theor Popul Biol 61:461–470. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.2002.1591

Rossmann MG, Arnold E, Erickson JW, Frankenberger EA, Griffith JP, Hecht HJ, Johnson JE, Kamer G, Luo M, Mosser AG et al (1985) Structure of a human common cold virus and functional relationship to other picornaviruses. Nature 317:145–153. https://doi.org/10.1038/317145a0

Roulin PS, Lotzerich M, Torta F, Tanner LB, van Kuppeveld FJ, Wenk MR, Greber UF (2014) Rhinovirus uses a phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate/cholesterol counter-current for the formation of replication compartments at the ER-Golgi interface. Cell Host Microbe 16:677–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2014.10.003

Benson SD, Bamford JK, Bamford DH, Burnett RM (1999) Viral evolution revealed by bacteriophage PRD1 and human adenovirus coat protein structures. Cell 98:825–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81516-0

Stromsten NJ, Bamford DH, Bamford JK (2003) The unique vertex of bacterial virus PRD1 is connected to the viral internal membrane. J Virol 77:6314–6321. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.77.11.6314-6321.2003

Liu H, Jin L, Koh SB, Atanasov I, Schein S, Wu L, Zhou ZH (2010) Atomic structure of human adenovirus by cryo-EM reveals interactions among protein networks. Science 329:1038–1043. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1187433

Yu X, Veesler D, Campbell MG, Barry ME, Asturias FJ, Barry MA, Reddy VS (2017) Cryo-EM structure of human adenovirus D26 reveals the conservation of structural organization among human adenoviruses. Sci Adv 3:e1602670. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1602670

Cardone G, Winkler DC, Trus BL, Cheng N, Heuser JE, Newcomb WW, Brown JC, Steven AC (2007) Visualization of the herpes simplex virus portal in situ by cryo-electron tomography. Virology 361:426–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.047

Condezo GN, San Martin C (2017) Localization of adenovirus morphogenesis players, together with visualization of assembly intermediates and failed products, favor a model where assembly and packaging occur concurrently at the periphery of the replication center. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006320. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006320

Ostapchuk P, Suomalainen M, Zheng Y, Boucke K, Greber UF, Hearing P (2017) The adenovirus major core protein VII is dispensable for virion assembly but is essential for lytic infection. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006455. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006455

Nikolic J, Lagaudrière-Gesbert C, Scrima N, Blondel D, Gaudin Y (2019) Structure and function of Negri bodies. In: Greber UF (ed) Physical virology – virus structure and mechanics. Springer, Berlin

San Martín C (2019) Virus maturation. In: Greber UF (ed) Physical virology – virus structure and mechanics. Springer, Berlin

Greber UF, Singh I, Helenius A (1994) Mechanisms of virus uncoating. Trends Microbiol 2:52–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0966-842X(94)90126-0

Imelli N, Ruzsics Z, Puntener D, Gastaldelli M, Greber UF (2009) Genetic reconstitution of the human adenovirus type 2 temperature-sensitive 1 mutant defective in endosomal escape. Virol J 6:174. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-422X-6-174

Kilcher S, Mercer J (2015) DNA virus uncoating. Virology 479–480:578–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2015.01.024

Suomalainen M, Greber UF (2013) Uncoating of non-enveloped viruses. Curr Opin Virol 3:27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2012.12.004

Evilevitch A, Roos WH, Ivanovska IL, Jeembaeva M, Jonsson B, Wuite GJ (2011) Effects of salts on internal DNA pressure and mechanical properties of phage capsids. J Mol Biol 405:18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.039

Klug WS, Roos WH, Wuite GJ (2012) Unlocking internal prestress from protein nanoshells. Phys Rev Lett 109:168104. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.168104

Greber UF (2014) How cells tune viral mechanics – insights from biophysical measurements of influenza virus. Biophys J 106:2317–2321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2014.04.025

Li S, Sieben C, Ludwig K, Hofer CT, Chiantia S, Herrmann A, Eghiaian F, Schaap IA (2014) pH-controlled two-step uncoating of influenza virus. Biophys J 106:1447–1456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.018

de Pablo PJ, Schaap IAT (2019) Atomic force microscopy of viruses. In: Greber UF (ed) Physical virology – virus structure and mechanics. Springer, Berlin

Pang HB, Hevroni L, Kol N, Eckert DM, Tsvitov M, Kay MS, Rousso I (2013) Virion stiffness regulates immature HIV-1 entry. Retrovirology 10:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4690-10-4

Burckhardt CJ, Greber UF (2009) Virus movements on the plasma membrane support infection and transmission between cells. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000621. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000621

Burckhardt CJ, Suomalainen M, Schoenenberger P, Boucke K, Hemmi S, Greber UF (2011) Drifting motions of the adenovirus receptor CAR and immobile integrins initiate virus uncoating and membrane lytic protein exposure. Cell Host Microbe 10:105–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2011.07.006

Strunze S, Engelke MF, Wang IH, Puntener D, Boucke K, Schleich S, Way M, Schoenenberger P, Burckhardt CJ, Greber UF (2011) Kinesin-1-mediated capsid disassembly and disruption of the nuclear pore complex promote virus infection. Cell Host Microbe 10:210–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.010

Bauer DW, Huffman JB, Homa FL, Evilevitch A (2013) Herpes virus genome, the pressure is on. J Am Chem Soc 135:11216–11221. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja404008r

Greber UF (2016) Virus and host mechanics support membrane penetration and cell entry. J Virol 90:3802–3805. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02568-15

Luisoni S, Greber UF (2016) Biology of adenovirus cell entry – receptors, pathways, mechanisms. In: Curiel D (ed) Adenoviral vectors for gene therapy. Academic Press, London, pp 27–58. ISBN: 9780128002766

Hernando-Perez M, Miranda R, Aznar M, Carrascosa JL, Schaap IA, Reguera D, de Pablo PJ (2012) Direct measurement of phage phi29 stiffness provides evidence of internal pressure. Small 8:2366–2370. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201200664

Branda MM, Guérin DMA (2019) Alkalinization of Icosahedral nonenveloped viral capsid interior through proton channeling. In: Greber UF (ed) Physical virology – virus structure and mechanics. Springer, Berlin

Martin-Gonzalez N, Guerin Darvas SM, Durana A, Marti GA, Guerin DMA, de Pablo PJ (2018) Exploring the role of genome and structural ions in preventing viral capsid collapse during dehydration. J Phys Condens Matter 30:104001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648X/aaa944

Greber UF, Willetts M, Webster P, Helenius A (1993) Stepwise dismantling of adenovirus 2 during entry into cells. Cell 75:477–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-8674(93)90382-Z

Nakano MY, Boucke K, Suomalainen M, Stidwill RP, Greber UF (2000) The first step of adenovirus type 2 disassembly occurs at the cell surface, independently of endocytosis and escape to the cytosol. J Virol 74:7085–7095. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.74.15.7085-7095.2000

Ortega-Esteban A, Bodensiek K, San Martin C, Suomalainen M, Greber UF, de Pablo PJ, Schaap IA (2015) Fluorescence tracking of genome release during mechanical unpacking of single viruses. ACS Nano 9:10571–10579. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.5b03020

Snijder J, Reddy VS, May ER, Roos WH, Nemerow GR, Wuite GJ (2013) Integrin and defensin modulate the mechanical properties of adenovirus. J Virol 87:2756–2766. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02516-12

Wang IH, Suomalainen M, Andriasyan V, Kilcher S, Mercer J, Neef A, Luedtke NW, Greber UF (2013) Tracking viral genomes in host cells at single-molecule resolution. Cell Host Microbe 14:468–480. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10040166

Jefferys EE, Sansom MPS (2019) Computational virology: molecular simulations of virus dynamics and interactions. In: Greber UF (ed) Physical virology – virus structure and mechanics. Springer, Berlin

Sbalzarini IF, Greber UF (2018) How computational models enable mechanistic insights into virus infection. Methods Mol Biol 1836:609–631. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-8678-1_30

Witte R, Andriasyan V, Georgi F, Yakimovich A, Greber UF (2018) Concepts in light microscopy of viruses. Viruses 10(4):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10040202

Summers WC (1993) How bacteriophage came to be used by the Phage Group. J Hist Biol 26:255–267. https://doi.org/10.1128/9781555816506.ch1

Evilevitch A (2013) Physical evolution of pressure-driven viral infection. Biophys J 104:2113–2114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2013.03.062

Yin J, Redovich J (2018) Kinetic modeling of virus growth in cells. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 82:e00066–00017. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.00066-17

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank all the authors for their valuable contributions, the reviewers of the chapters for insightful and constructive comments and Maarit Suomalainen for comments to the editorial text.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Greber, U.F. (2019). Editorial: Physical Virology and the Nature of Virus Infections. In: Greber, U. (eds) Physical Virology. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, vol 1215. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14741-9_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14741-9_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-14740-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-14741-9

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)