Abstract

The chapter examines the history and evolution of development doctrine. It suggests that the selection and adoption of a development strategy depend upon three building blocks: (1) the prevailing development objectives which, in turn, are derived from the prevailing view and definition of the development process; (2) the conceptual state of the art regarding the existing body of development theories, hypotheses, models, techniques, and empirical applications; and (3) the underlying data system available to diagnose the existing situation, measure performance, and test hypotheses. Development doctrine is then defined as the body of principles and knowledge resulting from the interrelated complex of these four elements that is accepted by the Development Community at that time. This analytical framework is applied to describe the state of the art that prevailed in each of the five decades (from the 1950s to the 1990s) and in the most recent period 2000 to 2017 to highlight in a systematic fashion the changing conception of the development process. Over the last 67 years the definition of development and strategies to achieve it, progressed and broadened from the maximization of GDP in the 1950s, to employment creation and the satisfaction of basic needs in the 1970s, to structural adjustment and stabilization in the 1980s and early 1990s, to poverty reduction, followed by sustainable and shared growth that dominated the scene until recently. The evolution in the conception of development culminated with the present broad-based concept of inclusive and sustainable growth. A parallel and similar progression occurred in development theory and in the coverage, comprehensiveness and quality of data and information. While development economics has followed a time path towards more experimental, multidisciplinary and more rigorous and scientific methodology, the present emphasis on microeconomic phenomena and randomized and controlled trials may have detracted researchers from exploring fundamental “big picture” macroeconomic phenomena.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- History of development economics

- Evolution of development doctrine

- Shifting development objectives

- History of development theories

1 Introduction

The economic and social development of the Third World, as such, was clearly not a policy objective of the colonial rulers before the Second World War.Footnote 1 Such an objective would have been inconsistent with the underlying division of labour and trading patterns within and among colonial blocks. It was not until the end of the colonial system in the late 1940s and 1950s, and the subsequent creation of independent states, that the revolution of rising expectations could start. Thus, the end of the Second World War marked the beginning of a new regime for the less developed countries involving the evolution from symbiotic to inward-looking growth and from a dependent to a somewhat more independent relation vis-à-vis the ex-colonial powers. It also marked the beginning of serious interest among scholars and policymakers in studying and understanding better the development process as a basis for designing appropriate development policies and strategies. In a broad sense a conceptual development doctrine had to be built which policymakers in the newly independent countries could use as a guideline to the formulation of economic policies.

A compelling case can be made that development economics, more so than any other branch of economics, should be both positive and normative. It should be positive to investigate micro and macro phenomena as objectively as possible. This means that the concepts, theories and techniques used to examine the behaviour of actors under different settings and initial conditions should be as value-free as possible. However, just as in quantum physics the Bohr-Heisenberg principle may hold in economics, as well, in the sense that there is no reality independent of the observer and the instruments used in capturing that reality. All theories (such as the neo-classical framework) and techniques (such as the randomised controlled experiments that have become the gold standard of the present generation of researchers) used in the analysis of development phenomena act as lenses that distort somewhat the outside reality.

At the same time development economists have a crucial normative role to play in trying to express social welfare functions in different settings that are consistent with the highest attainable and sustainable levels of well-being over time given the limited resources available. This is a most difficult and even controversial task. In many respects, development economists by investigating the likely consequences of alternative policy scenarios can help identify those scenarios that provide the highest feasible levels of well-being for the groups under consideration. In this sense development economics can become the conscience of economics.Footnote 2

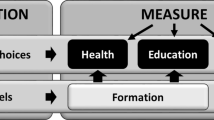

The selection and adoption of a development strategy—that is, a set of more or less interrelated and consistent policies—depend upon three building blocks: (1) the prevailing development objectives which, in turn, are derived from the prevailing view and definition of the development process; (2) the conceptual state of the art regarding the existing body of development theories, hypotheses, models, techniques and empirical applications; and (3) the underlying data system available to diagnose the existing situation, measure performance and test hypotheses. Figure 3.1 illustrates the interrelationships and interdependence which exist among (1) development theories and models, (2) objectives, (3) data systems and the measurement of performance and (4) development policies, institutions and strategies, respectively. These four different elements are identified in four corresponding boxes in Fig. 3.1. At any point in time or for any given period, these four sets of elements (or boxes) are interrelated. We define development doctrine as the body of principles and knowledge resulting from the interrelated complex of these four elements that is generally accepted by the development community at that time.

Thus, it can be seen from Fig. 3.1 that the current state of the art, which is represented in the southwest box embracing developments theories, hypotheses and models, affects and is, in turn, affected by the prevailing development objectives—hence the two arrows in opposite directions linking these two boxes. Likewise, data systems emanate from the existing body of theories and models and are used to test prevailing development hypotheses and to derive new ones. Finally, the choice of development policies and strategies is jointly determined and influenced by the other three elements—objectives, theories and data, as the three corresponding arrows indicate.Footnote 3

The analytical framework presented earlier and outlined in Fig. 3.1 is applied to describe the state of the art that prevailed in each of the five decades (from the 1950s to the 1990s) and in the most recent period 2000–2017 to highlight in a systematic fashion the changing conception of the development process. The choice of the decade and that of the longer most recent period (2000–2017), as relevant time periods, is of course arbitrary. So is, to some extent, the determination of the most important contributions in each of the categories (boxes) shown in Fig. 3.1 for each of the six periods under consideration.Footnote 4 While I fully recognise that the choice of these contributions ultimately reflects my own subjective evaluation, I tried hard to reflect the consensus views of the professional development community as it evolved over time.Footnote 5

Figures 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, 3.5, 3.6 and 3.7 attempt to identify for each period the major elements which properly belong in the four interrelated boxes. In a certain sense it can be argued that the interrelationships among objectives, theories and models, data systems and hypotheses and strategies constitute the prevailing development doctrine for a given period. A brief sequential discussion of the prevailing doctrine in each of the six consecutive periods provides a useful way of capturing the evolution that development theories and strategies have undergone. A final section sums up and concludes.

2 The Development Doctrine During the 1950s

Economicgrowth became the main policy objective in the newly independent less developed countries. It was widely believed that through economic growth and modernisation per se, dualism and associated income and social inequalities which reflected it, would be eliminated. Other economic and social objectives were thought to be complementary to—if not resulting from—gross national product (GNP) growth. Clearly, the adoption of GNP growth as both the objective and yardstick of development was directly related to the conceptual state of the art in the 1950s. The major theoretical contributions which guided the development community during that decade were conceived within a one-sector, aggregate framework and emphasised the role of investment in modern activities. The development economists’ tool kit in the 1950s contained such theories and concepts as the ‘big push’ (Rosenstein-Rodan 1943), ‘balanced growth’ (Nurkse 1953), ‘take-off into sustained growth’ (Rostow 1956) and ‘critical minimum effort thesis’ (Leibenstein 1957) (see Fig. 3.2).

What all these concepts have in common, in addition to an aggregate framework, is equating growth with development and viewing growth in less developed countries as essentially a discontinuous process requiring a large and discrete injection of investment. The ‘big push’ theory emphasised the importance of economies of scale in overhead facilities and basic industries. The ‘take-off’ principle was based on the simple Harrod–Domar identity that for the growth rate of income to be higher than that of the population (so that per capita income growth is positive), a minimum threshold of the investment to GNP ratio is required given the prevailing capital–output ratio. In turn, the ‘critical minimum effort thesis’ called for a large discrete addition to investment to trigger a cumulative process within which the induced income-growth forces dominate induced income-depressing forces. Finally, Nurkse’s ‘balanced growth’ concept stressed the external economies inherent on the demand side in a mutually reinforcing and simultaneous expansion of a full set of complementary production activities which combine to increase the size of the market. It does appear, in retrospect, that the emphasis on large-scale investment in the 1950s was strongly influenced by the relatively successful development model and performance of the Soviet Union between 1928 and 1940.

The same emphasis on the crucial role of investment as a prime mover of growth is found in the literature on investment criteria in the 1950s. The key contributions were (1) the ‘social marginal production’ criterion (Kahn 1951 and Chenery 1953), (2) the ‘marginal per capita investment quotient’ criterion (Galenson and Leibenstein 1955) and (3) the ‘marginal growth contribution’ criterion (Eckstein 1957).

It became fashionable to use as an analytical framework one-sector models of the Harrod–Domar type which, because of their completely aggregated and simple production functions, with only investment as an element, emphasised at least implicitly investment in infrastructure and industry. The reliance on aggregate models was not only predetermined by the previously discussed conceptual state of the art but also by the available data system which, in the 1950s, consisted almost exclusively of national income accounts. Disaggregated information in the form of input–output tables appeared in the developing countries only in the 1960s.

The prevailing development strategy in the 1950s follows directly and logically from the previously discussed theoretical concepts. Industrialisation was conceived as the engine of growth which would pull the rest of the economy along behind it. The industrial sector was assigned the dynamic role in contrast to the agricultural sector which was, typically, looked at as a passive sector to be ‘squeezed’ and discriminated against. More specifically, it was felt that industry, as a leading sector, would offer alternative employment opportunities to the agricultural population, would provide a growing demand for foodstuffs and raw materials and would begin to supply industrial inputs to agriculture.

Under this ‘industrialisation-first strategy’, the discrimination in favour of industry and against agriculture took several forms. First, in many countries, the internal terms of trade were turned against agriculture through a variety of price policies which maintained food prices at an artificially low level in comparison with industrial prices. Another purpose of these price policies—in addition to extracting resources from agriculture—was to provide cheap food to the urban workers and thereby tilt the income distribution in their favour.

A major means of fostering industrialisation, at the outset of the development process, was through import substitution—particularly of consumer goods and consumer durables. With very few exceptions the whole gamut of import-substitution policies, ranging from restrictive licencing systems, high protective tariffs and multiple exchange rates to various fiscal devices, sprang up and spread rapidly in developing countries. This inward-looking approach to industrial growth led to the fostering of many highly inefficient industries.

The infant–industry argument provided the rationale for the emphasis on investing in the urban modern sector in import-substituting production activities and physical infrastructure. While there is some validity to this thesis, in most instances, the import-substitution process followed by most developing countries relied on too much protection over too long a period.

3 The Development Doctrine During the 1960s

Figure 3.3 captures the major elements of the development doctrine prevailing in the 1960s. On the conceptual front the decade of the 1960s was dominated by an analytical framework based on economic dualism. Whereas the development doctrine of the 1950s implicitly recognised the existence of the backward part of the economy complementing the modern sector, it lacked the dualistic framework to explain the reciprocal roles of the two sectors in the development process. The naive two-sector modelsà la Lewis (1954) continued to assign to subsistence agriculture an essentially passive role as a potential source of ‘unlimited labour’ and ‘agricultural surplus’ for the modern sector. It was assumed that the marginal productivity of labour in traditional agriculture was zero and, hence, that farmers could be released from subsistence agriculture in large numbers without a consequent reduction in agricultural output while simultaneously carrying their own bundles of food (i.e. capital) on their backs or at least having access to it.

As the dual-economy models became more sophisticated, the interdependence between the functions that the modern industrial and backward agricultural sectors must perform during the growth process was increasingly recognised (Fei and Ranis 1964). The backward sector had to release resources for the industrial sector, which in turn had to be capable of absorbing them. However, neither the release of resources nor the absorption of resources, by and of themselves, was sufficient for economic development to take place. Recognition of this active interdependence was a large step forward from the naive industrialisation-first prescription because the conceptual framework mentioned earlier no longer identified either sector as leading or lagging.

A gradual shift of emphasis took place regarding the role of agriculture in development. Rather than considering subsistence agriculture as a passive sector whose resources had to be squeezed to fuel the growth of industry and to some extent modern agriculture, it started to become apparent in the second half of the 1960s that agriculture could best perform its role as a supplier of resources by being an active and co-equal partner with modern industry. This meant in concrete terms that a gross flow of resources from industry to agriculture could be crucial at an early stage of development to generate an increase in agricultural output and productivity which would facilitate the extraction of a new transfer out of agriculture and into the modern sector. The trouble with the alternative approach which appears to have characterised the 1950s of squeezing agriculture too hard or too early in the development process was described in the following graphic terms: “The backwards agricultural goose would be starved before it could lay the golden egg” (Thorbecke 1969, p. 3).

The ‘balanced’ versus ‘unbalanced’ growth issue was much debated during the 1960s. In essence, the balanced growth thesis (Nurkse 1953) emphasised the need for the sectoral growth of output to be consistent with the differential growth of demand for different goods as income rises. Unbalanced growth, on the other hand, identified the lack of decision-making ability in the private and public sectors as the main bottleneck to development (Hirschman 1958). The prescription for breaking through this bottleneck was to create a sequence of temporary excess capacity of social overhead facilities which, by creating a vacuum and an attractive physical environment, would encourage the build-up of directly productive activities. Alternatively, the process could start by a build-up of directly productive activities ahead of demand, which, in turn, would generate a need for complementary social overhead projects.

The similarities between the balanced and unbalanced growth theses are more important than their apparently different prescriptions. Both approaches emphasised the role of inter-sectoral linkages in the development process. In a certain sense they extended the dual-economy framework to a multi-sectoral one without, however, capturing the essential differences in technology and form of organisation between modern and traditional activities. This was at least partially due to the type of sectoral disaggregation available in the existing input–output tables of developing countries during the 1960s. Except for the various branches of industry, the level of sectoral aggregation tended to be very high, with agricultural and service activities seldom broken down in more than two or three sectors.

Another contribution of the late 1960s which was imbedded in inter-sectoral (input–output) analysis is the theory of effective protection, which clarified and permitted the measurements of the static efficiency cost of import substitution when both inputs and outputs are valued at world prices.

Still another important set of contributions that appeared in the 1960s relates to the inter-sectoral structure and pattern of economic growth. Two different approaches provided important insights into the changing inter-sectoral structure of production and demand throughout the process of economic development. The first approach, based largely on the work of Kuznets (1966), relied on a careful and painstaking historical analysis of a large number of countries. The second approach was pioneered by Hollis Chenery and based on international cross-sectional analysis which was subjected to regression analysis to derive what appeared to be structural patterns in the process of growth (Chenery 1960 and Chenery and Taylor 1968).

The conception of economic development in the 1960s was still largely centred on GNP growth as the key objective. In particular, the relationship between growth and the balance of payments was made clearer. Towards the end of this decade the increasing seriousness of the un- and underemployment problem in the developing world led to a consideration of employment as an objective in its own right next to GNP growth. The most noteworthy change in the conception of development was the concern for understanding better the inter-sectoral structure and physiology of the development process—as the preceding review of the conceptual state of the art revealed.

It is important to observe, in retrospect, that a deep-rooted pessimism prevailed about the development prospects of Asia, somewhat in contrast with the rosier prospects of the Latin America region, among some of the leading analysts. Gunnar Myrdal’s Asian Drama (1968) painted an almost desperate picture of the Asian socio-economic future, ironically, just as the East Asian Miracle was starting in Taiwan and South Korea.

The development policies and strategies that prevailed in the 1960s flowed directly from the conceptual contributions, development objectives and the data system. These policies fall into a few categories, which are reviewed briefly later. The first set embraces the neo-classical prescription and can be expressed under the heading of ‘fine-tuning’ and ‘appropriate prices’. In a nutshell the ‘fine-tuning’ instruments embrace the use of an appropriate price system (including commodity, tax and subsidy rates), the removal of market imperfections and appropriate exchange rate and commercial policies.

A second set of policies can be classified as essentially structural, emphasising the importance of inter-sectoral linkages. They include the allocation of investment and current public expenditures among sectors, so as to achieve a process of inter-sectoral balanced (or, in some instances, unbalanced) growth. More specifically, by the late 1960s agriculture was assigned a much more active role in the development process. The provision of a greater level of public resources to that sector—combined with less discriminatory price policies—was expected to result in a growth of output and productivity which would facilitate a net transfer back to the rest of the economy. The success of South Korea and Taiwan in nurturing their agricultural sector and using the agricultural surplus to achieve a successful industrial take-off was starting to resonate.

4 The Development Doctrine in the 1970s

Figure 3.4 summarises the major development objectives, theories, data sources and policies prevailing in the 1970s. By the 1970s the failure of a GNP-oriented development strategy to cope successfully with increasingly serious development problems in much of the Third World led to a thorough re-examination of the process of economic and social development. The major development problems that became acute and could no longer be ignored during this decade can be summarised as: (1) the increasing level and awareness of un- and underemployment in a large number of developing countries; (2) the tendency for income distribution within countries to have become more unequal or, at least, to have remained as unequal as in the immediate post–Second World War period; (3) the maintenance of a very large and rising share and absolute number of individuals in a state of poverty, that is, below some normative minimum income level or standard of living; (4) the continuing and accelerating rural–urban migration and consequent urban congestion and finally (5) the worsening external position of much of the developing world reflected by increasing balance-of-payments pressures and rapidly mounting foreign indebtedness and debt servicing burdens. Largely because of these closely interrelated problems, a less unequal income distribution, particularly in terms of a reduction in absolute poverty, was given a much greater weight in the preference function of most developing countries compared to the objective of aggregate growth per se. Furthermore, this reduction in absolute poverty was to be achieved mainly through increased productive employment (or reduced underemployment) in the traditional sectors.

By the mid-1970s, GNP as a dominant all-encompassing objective had been widely, but by no means universally, dethroned. The presumption that aggregate growth was synonymous with economic and social development or, alternatively, that it would ensure the attainment of all other development objectives, came under critical scrutiny and was rejected in many circles. The launching of the World Employment Programme by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in 1969 signalled that the primary objective should be to raise the standard of living of the poor through increased employment opportunities. The generation of new or greater productive opportunities was considered a means towards the improvement of the welfare of the poor.

The changing meaning of development as a process that should have as simultaneous objectives growth and poverty alleviation both influenced and was influenced by several conceptual and empirical contributions. The first set of contributions comes under the rubric of integrated rural and agricultural development. A whole series of empirical studies at the micro and macro levels combined to provide an explanation of the physiology and dynamics of the transformation process of traditional agriculture. This body of knowledge provided a rationale for a unimodal strategy in the rural areas, which is discussed subsequently under the strategy box.

A second type of conceptual breakthroughs which appeared in the 1970s was that on the role of the informal sector and that of employment in furthering the development process. Even though the informal sector concept had been around a long time and taken a variety of forms such as Gandhi’s emphasis on traditional cottage industries, it became revitalised in a more general and formal sense in the Kenya Report of the ILO (ilo1973). A number of case studies undertaken by ILO focussing specifically on the role of the informal sector concluded that it was relatively efficient, dynamic and often strongly discriminated against because of market imperfections or inappropriate national or municipal regulations. These studies suggested that informal activities represent an important potential source of output and employment growth.

A third contribution which surfaced in the 1970s includes the interdependence between economic and demographic variables and the determinants of the rural–urban migration. Many empirical studies, mainly at the micro level, attempted to throw some light on the relationship between such sets of variables as (1) education, nutrition and health and (2) fertility, infant mortality and, ultimately, the birth rate. The hypotheses that were generated by these studies highlighted the complex nature of the causal relationship between population growth and economic development and suggested that the Malthusian tragedy could be overcome by appropriate educational and birth control policies.

Regarding the determinants of migration, the initial Harris–Todaro (1970) formulation triggered a series of empirical studies and simple models of the migration process. In general, migration was explained as a function of urban–rural wage differentials weighted by the probability of finding urban employment.

A somewhat parallel set of contributions at the micro level consisted of the attempt at incorporating socio-economic objectives—such as employment and income distribution—among investment (benefit-cost) criteria and in the appraisal and selection of projects (Little and Mirrlees 1974).

A review of contributions to the state of the art in development economics during this decade would not be complete without at least a reference to the neo-Marxist literature on underdevelopment and dependency theories. The essence of these theories is that underdevelopment is intrinsic in a world trading and power system in which the developing countries make up the backward, raw-material-producing periphery and the developed countries the modern-industrialised centres (Hunt 1989). A neo-colonial system of exploitation by indigenous classes associated with foreign capital (e.g. multinational corporations) was considered to have replaced the previous colonial system. The Prebisch-Singer thesis, arguing that the terms of trade of primary products relative to manufactured goods would decline over time, provided a rationale to implement protectionist policies and was particularly popular in Latin America.

The coverage and quality of the data available improved substantially in the 1970s. By the mid-1970s survey-type information on variables such as employment, income, consumption and saving patterns was becoming available. A variety of surveys covering such diverse groups as urban, informal and rural households started to provide valuable information on the consumption and savings behaviour of different socio-economic groups. In some developing countries it became possible, for the first time, to estimate approximately the income distribution by major socio-economic groups.

In this context, the pioneering work of Irma Adelman and her collaborators of visualising the process of development as the product of multiple economic and non-economic variables interacting over time to determine the structure of growth and income distribution within a general equilibrium framework was a major breakthrough in unveiling the multi-dimensional and dynamic nature of this process (Adelman and Robinson 1978; Adelman and Morris 1967).

After having reviewed the changing development objectives, conceptual contributions and data sources which marked the 1970s, the next logical step is to describe and analyse briefly the new development strategies that emerged. From a belief that growth was a necessary and sufficient condition for the achievement of economic and social development, it became increasingly recognised that even though necessary, growth might not be sufficient. The first step in the broadening process of moving from a single to multiple development objectives was a concern with, and incorporation of, employment in development plans and in the allocation of foreign aid to projects and technical assistance.

One possible attraction of using employment as a target was that it appeared, on the surface, to be relatively easily measurable—in somewhat the same sense as the growth rate of gnp had provided previously a simple scalar measure of development. Yet, as was soon realised, the measurement of informal labour and part-time labour proved to be fraught with difficulties. The real and fundamental goal was an improvement in the standards of living of all groups in society and, especially, that of the poorest and most destitute groups.

Two partially overlapping variants of a distribution-oriented strategy surfaced during this decade. These were ‘redistribution with growth’ and ‘basic needs’. The first one was essentially incremental in nature, relying on the existing distribution of assets and factors and requiring increasing investment transfers in projects (mostly public but perhaps even private) benefiting the poor (Chenery et al. 1974). The first step in this strategy was the shift in the preference (welfare) function away from aggregate growth per se towards poverty reduction.

The second alternative strategy inaugurated during the 1970s was the basic needs strategy, which was particularly advocated by the ilo.Footnote 6 It entailed structural changes and some redistribution of the initial ownership of assets—particularly land reform—in addition to a set of policy instruments, such as public investment. Basic needs, as objectives defined by ILO, included two elements: (1) certain minimal requirements of a family for private consumption, such as adequate food, shelter and clothing and (2) essential services provided by and for the community at large, such as safe drinking water, sanitation, health and educational facilities.

A complementary policy within the agricultural sector was that of integrated rural development. In a nutshell, the novel approach centred on lending and technical activities benefiting directly the traditional sector. This strategy conformed to a broader so-called unimodal agricultural development strategy (Johnston and Kilby 1975). The latter relied on the widespread application of labour-intensive technology to the whole of agriculture. In this sense, it was based on the progressive modernisation of agriculture ‘from the bottom up’ to start and facilitate the dynamic structural transformation so fundamental to the growth process. Structural transformation involves four key features: a falling share of agriculture in economic output and employment; a rising share of urban economic activity in industry and modern services; migration of rural workers to urban settings; and a demographic transition (Timmer 2015).

A third type of development strategy follows from the neo-Marxist underdevelopment and dependency theories, which have been previously touched upon. This approach was radical, if not revolutionary, in nature. It called for a massive redistribution of assets to the state and the elimination of most forms of private property. It appeared to favour a collectivistic model—somewhat along the lines of the Chinese regime in power at that time—based on self-reliance and the adoption of indigenous technology and forms of organisation.

5 The Development Doctrine in the 1980s

A combination of events including an extremely heavy foreign debt burden—reflecting the cumulative effects of decades of borrowing and manifested by large and increasing balance-of-payments and budget deficits in most of the developing world—combined with higher interest rates and a recession in creditor countries changed radically the development and aid environment at the beginning of the 1980s. The Mexican financial crisis of 1982 soon spread to other parts of the Third World. The magnitude of the debt crisis was such that, at least for a while, it brought into question the survival of the international financial system.

Suddenly, the achievement of external (balance-of-payments) equilibrium and internal (budget) equilibrium became the overarching objectives and necessary conditions to the restoration of economic growth and poverty alleviation. The debt crisis converted the 1980s into the ‘lost development decade’. Before the development and poverty alleviation path could be resumed, the Third World had to put its house in order and implement painful stabilisation and structural adjustment policies.

Notwithstanding the fact that the development process was temporarily blocked and most of the attention of the development community was focussed on adjustment and stabilisation issues, some important contributions to development theory were made during this decade (see Fig. 3.5).

The first one greatly enriched our understanding of the role of human capital as a prime mover of development. The so-called endogenous growth school (Lucas 1988 and Romer 1990) identifies low human capital endowment as the primary obstacle to the achievement of the potential scale economies that might come about through industrialisation. In a societal production function, raw (unskilled) labour and capital were magnified by a term representing human capital and knowledge, leading to increasing returns. This new conception of human capital helped convert technical progress from an essentially exogenously determined factor to a partially endogenously determined factor. Progress was postulated to stem from two sources: (1) deliberate innovations, fostered by the allocation of resources (including human capital) to research and development (R&D) activities and (2) diffusion, through positive externalities and spill-overs from one firm or industry to know-how in other firms or industries (Ray 1998: Ch. 4). If investment in human capital and know-how by individuals and firms is indeed subject to increasing returns and externalities, it means that the latter do not receive the full benefits of their investment resulting, consequently, in under-investment in human capital (the marginal social productivity of investment in human capital being larger than that of the marginal private productivity).

A second contribution based on quantitative and qualitative empirical studies—relying on international cross-sectional and country-specific analyses of performance over time—was the robust case made for the link between trade and growth. Outward orientation was significantly and strongly correlated with economic growth. Countries that liberalised and encouraged trade grew faster than those that followed a more inward-looking strategy. The presumed mechanism linking export orientation to growth is based on the transfer of state of the art technology normally required to compete successfully in the world market for manufactures. In turn, the adoption of frontier technology by firms adds to the human capital of those workers and engineers through a process of ‘learning-by-doing’ and ‘learning-by-looking’ before spilling over to other firms in the same industry and ultimately across industries.

A third set of contributions to development theories that surfaced in the 1980s can be broadly catalogued under the heading of the ‘new institutional economics’ and collective action (North 1990, Williamson 1991 and Nabli and Nugent 1989). As de Janvry et al. (1993, p. 565) noted, “The main advance was to focus on strategic behavior by individuals and organised groups in the context of incomplete markets. The theories of imperfect and asymmetrical information and, more broadly, transaction costs gave logic to the role of institutions as instruments to reduce transactions costs.” The neo-institutional framework, in addition to reminding the development community that appropriate institutions and rules of the game are essential to provide pro-development and anti-corruption incentives, also suggested broad guidelines in building institutions that reduced the scope for opportunistic behaviour.

Another contribution of this approach was to provide a clear rationale for the existence of efficient non-market exchange configurations, particularly in the rural areas. Proto-typical examples of such institutions include intra-farm household transactions; two-party contracts (e.g. sharecropping and interlinked transactions), farmers’ co-operatives and group organisations, mutual insurance networks and informal credit institutions (Thorbecke 1993). Those exchange non-market configurations—called agrarian institutions by Bardhan (1989)—owe their existence to lower transaction costs than those that would prevail in an alternative market configuration providing an equivalent good, factor or service. In most instances market imperfections or, at the limit, market failure (in which case there is no alternative market configuration and transaction costs become infinite) are at the origin of non-market configurations.

The decade of the 1980s witnessed some seminal contributions to a better understanding of the concept of poverty and its measurement. A comprehensive and operationally useful approach to poverty analysis was developed by Amartya Sen (1985) in his ‘capabilities and functioning’ theoretical framework. According to this framework what ultimately matters is the freedom of a person to choose her functionings. In order to function, an individual requires a minimum level of well-being brought about by a set of attributes. In turn, the Foster-Greer-Thorbecke (1984) class of decomposable poverty measures allowed poverty to be measured while satisfying most important welfare axioms.

A final contribution worth noting—which can be subsumed under the ‘new institutional economies’ heading—is that of interlinked transactions (Bardhan 1989). An interlinked contract is one in which two or more interdependent exchanges are simultaneously agreed upon (e.g. when a landlord enters into a fixed-rent agreement with a tenant and also agrees to provide credit at a given interest rate). In a more general sense, this type of contract leads to interlocking factor markets for labour, credit and land. In retrospect it is somewhat ironical that during a decade dominated by a faith in the workings of markets—as is discussed subsequently—important theoretical contributions were made that highlighted market imperfections and failures.

On the modelling front, some important contributions to general equilibrium modelling appeared during the 1980s (Dervis et al. 1982). These models—calibrated on a base year social accounting matrix (SAM) reflecting the initial (base year) socio-economic structure of the economy—proved particularly useful in tracing through and simulating the impact of a variety of exogenous shocks and policies (such as a devaluation, trade liberalisation and fiscal reforms) on the income distribution by socio-economic household groups.

The 1980s witnessed a proliferation of statistical information on a variety of dimensions of development and the welfare of households. Besides more elaborate and disaggregated employment, manufacturing, agricultural and demographic surveysFootnote 7 and censuses, large-scale household income and expenditure surveys produced by statistical offices of most developing countries—and often designed and funded by the World Bank (e.g. the Living Standard Measurement Surveys)—became available to analysts and policymakers. Perhaps for the first time, reasonably reliable and robust observations could be derived relating to the magnitude of poverty, the characteristics of the poor and the inter-household income distribution. In turn, the various data sources could be combined to build SAMs of a large number of countries.

The development strategy of the 1970s—centred on redistribution with growth and fulfilment of basic needs—was replaced by an adjustment strategy. The magnitude of the debt crisis and the massive internal and external disequilibrium faced by most countries in Africa and Latin America and some in Asia meant that adjustment became a necessary (although not sufficient) condition to a resumption of development.

The main policy objective of Third World governments became macroeconomic stability, consisting of a set of policies to reduce their balance-of-payments deficits (e.g. devaluation) and their budget deficits (through retrenchment). Whereas stabilisation per se was meant to eliminate or reduce the imbalance between aggregate demand and aggregate supply, both externally and internally, structural adjustment was required to reduce distortions in relative prices and other structural rigidities that tend to keep supply below its potential. A typical adjustment package consisted of measures such as a devaluation, removal of artificial price distortions, trade liberalisation and institutional changes at the sector level.

Under the influence of ideological changes in the Western world (e.g. the Reagan and Thatcher administrations), developing countries were strongly encouraged—if not forced—to rely on the operation of market forces and in the process to minimise government activities in most spheres—not just productive activities.

Inherent contradictions and conflicts arose among the elements of the broad adjustment strategy of the 1980s. The successful implementation of adjustment policies called for a strong government. Likewise, the rationale for a larger role of government in the education sphere to generate the social spill-over effects and counteract the under-investment in education by private agents, who do not capture the positive externalities of their investment, ran counter to the objective of a minimalist state.

In this decade, characterised by pro-market and anti-government rhetoric, there was strong sentiment to do away with aid altogether and have private capital flows substitute for it. Thus, in the early 1980s, the Reagan administration created a fertile environment for conservative critics of foreign aid who felt that “economic assistance distorts the free operation of the market and impedes private-sector development” (Ruttan 1996, p. 143). Clearly, the debt overhang put a damper on going too far in eliminating aid. Both public and private creditors in the industrialised world had too much at stake.

6 The Development Doctrine in the 1990s

In the first half of the 1990s, stabilisation and adjustment were still the dominant objectives (see Fig. 3.6). While most of the Latin American countries (and the few Asian countries affected by the debt crisis) had gone through a painful adjustment process and were back on a growth path, the overall situation was still one of stagnation in much of the developing world—largely caused by poor governance in sub-Saharan Africa and most transition economies in Eastern Europe. It was becoming increasingly clear to the development community that fundamental and deep-rooted institutional changes to facilitate a successful transition from socialism and command economies to market economies and reduce corruption were a precondition to successful adjustment and a resumption of development in Eastern Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. Potentially the institutions and policies at the root of the East Asian ‘miracle’ could provide the model to follow.

In the second half of the 1990s, the Asian financial crisis hit East and Southeast Asia with a vengeance, resulting in a sharp reversal of the long-term poverty reduction trend. Simultaneously socio-economic conditions deteriorated so drastically in the former Soviet Republics that poverty alleviation in its broadest sense—including improvements in health, nutrition, education, access to information and to public goods and a participation in decision-making—resurfaced as the major, if not overarching, objective of development.

Another consequence of the financial crisis was to bring into question the Washington Consensus of unbridled capital and trade liberalisation and complete deregulation of the financial system. Several East and Southeast Asian countries were still suffering from the extreme deregulation of the banking sector and capital flows that weakened the supervisory and monitoring functions of central banks and other institutions. To protect their balance of payments, a number of affected countries were restoring controls on an ad hoc basis. The international monetary and financial system that still relied on the outdated Bretton Woods rules of the game needed major revamping and a new set of rules befitting the contemporaneous environment. These crises triggered a re-examination of the role of government in protecting the economy from major shocks originating abroad. In particular, it pointed towards strengthening financial institutions and the provision of the minimum set of rules and regulations (e.g. improved monitoring and supervision of the banking sector, and higher own capital reserves for individual banks) to reduce corruption and speculative borrowing from abroad; and the establishment of institutional safety nets that could act as build-in-stabilisers following a crisis.

The pernicious effects of a series of financial crises worldwide including the Japanese credit bubble, the US junk bonds and savings and loans’ crises and the Mexican tequila crisis in addition to the Asian financial crisis, perhaps for the first time forced the world economy to face the issue of building a sustainable global financial system. It was also in this decade that the aid community formally recognised and accepted the concept of sustainable development at the United Conference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992.Footnote 8Sustainability in many of its dimensions became an integral part and objective of development.

The conceptual contribution to development theory in the 1990s, in general, extended and further elaborated on earlier concepts. Perhaps the most fundamental issue that was debated during the 1990s is the appropriate roles of the state and the market, respectively, in development. An inherently related issue was to identify the set of institutions most conducive to the acceleration of the process of economic growth and socio-economic development. Prior to the onset of the Asian financial crisis, it was felt that the mix of institutions and policies adopted by the East Asian countries that gave rise to the East Asian miracle (World Bank 1993) provided a broad model, with parts of it potentially transferable to other developing countries. The financial crisis led to a more sceptical appraisal—even, among some circles, whether the miracle, after all, was not a ‘myth’.

In any case, the reliance on government actions in the previous decades to promote industrial growth on the part of East Asian countries (particularly, South Korea) appeared suspect and came under heavy criticism. Some critics argued that the already impressive growth performance would have been even better with less government intervention—and that even if those industrial policies had contributed to growth, they required a strong state, an element sorely missing in other parts of the Third World.

The role of institutions as a precondition to following a successful development path became even more critical if one subscribed to a new approach to political economy that takes institutions as largely given exogenously and argues that policies tend to be determined endogenously within a specific institutional context (Persson and Tabellini 1990). Thus, for example, if the central bank and the ministry of finance are not independent or are operating under loose discretionary rules, the monetary and fiscal policies that result will depend on political and social factors (or according to the political power of the different lobbies in society and the public choice formulation).

Two additional contributions worth highlighting in this decade are the concept of social capital and a better understanding of sources of growth (total factor productivity) and the need to explain the residual. Social capital was devised as a concept to complement human capital. If individuals are socially excluded, or marginalised, or systematically discriminated against, they cannot rely on the support of networks from which they are sealed off. Alternatively, membership in group organisations brings about benefits that can take a variety of forms (e.g. the provision of informal credit and help in the search for employment). The acquisition of social capital by poor households appeared particularly important as a means to help them escape from some poverty traps.

The spectacular growth of East Asian countries prior to 1997 renewed the interest in identifying, explaining and measuring the sources of growth. Several studies tended to demystify the East Asian miracle by suggesting that the rapid growth of these economies depended on resource accumulation with little improvement in efficiency and claimed that such growth was not likely to be sustainable (Krugman 1994, Kim and Lau 1994 and Young 1995). This conclusion was based on estimates of total factor productivity (TFP) growth and depended crucially on the form of the production function used and on an accurate measurement of the capital and labour inputs. Whatever residual was left over was ascribed to technological progress. Some critics argued that typical TFP calculations significantly underestimated organisational improvements within firms or what Leibenstein called x-efficiency.

The 1990s witnessed a renewed interest in computable general equilibrium (CGE) models used to simulate the impact of exogenous shocks and changes in policies on the socio-economic system and particularly income distribution. A key issue explored in those models was that of the impact of adjustment policies on income distribution and poverty. General equilibrium models provide the only technique to compare the impact of alternative (counterfactual) policy scenarios, such as a comparison of the effects of an adjustment programme versus a counterfactual non-adjustment programme (e.g. Thorbecke 1991 for Indonesia and Sahn et al. 1996 for Africa).

This decade was marked by a proliferation of statistical information relating particularly to the socio-economic characteristics and welfare of households—in addition to the more conventional data sources previously collected (see data box in Fig. 3.6). A large number of quantitative poverty assessments based on household expenditure surveys were completed, as well as more qualitative participatory poverty assessments. Furthermore, the availability of demographic and health surveys for many developing countries provided micro-level information on health and nutritional status, assets and access to public goods and services to supplement information on household consumption. Also, perhaps for the first time, the availability of multiple-year surveys and panel data for many countries allowed reliable standard of living and welfare comparisons to be made over time.

In many respects, the development strategy of the 1990s was built upon the foundations of the preceding decade and retained most of the latter’s strategic elements—at least in the first half of the decade. However, as the decade evolved, the adjustment-based strategy of the 1980s came under critical scrutiny that led to major changes—particularly in the wake of the Asian financial crisis.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the great majority of the countries were still facing serious adjustment problems. A widely debated issue was whether adjustment policies per se without complementary reforms—within the context of Africa—could provide the necessary initial conditions for a take-off into sustained growth and poverty alleviation. Two conflicting approaches to adjustment and diagnoses of its impact on performance were put forward. The ‘orthodox’ view, best articulated by the World Bank (at the beginning of the decade but subsequently modified), argued that an appropriate stabilisation and adjustment package pays off. Countries that went further in implementing that package experienced a turnaround in their growth rate and other performance indicators.

In contrast, the ‘heterodox’ approach—best articulated by the concept of ‘adjustment with a human face’, embraced by the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) (see Cornia et al. 1987)—while supporting the need for adjustment, argued that the orthodox reforms focus extensively on short-term stabilisation and did not address effectively the deep-rooted structural weaknesses of African economies that were the main causes of macro instability and economic stagnation. Accordingly, major structural and institutional changes were needed to complement adjustment policies to induce the structural transformation (such as industrialisation, diversification of the export base, the build-up of human capital and even land reform) without which sustainable long-term growth in Africa (and by extension in other developing countries facing similar initial conditions) was not deemed possible.

The UNICEF and heterodox critical evaluation of the impact of adjustment policies on long-term growth and poverty alleviation—even when it could not be appropriately verified on empirical grounds—sensitised multilateral and bilateral donors to the need to focus significantly more on the social dimensions of adjustment. It made a strong case for the implementation of a whole series of complementary and reinforcing reforms, ranging from greater emphasis on and investment in human capital and physical infrastructure to major institutional changes—particularly in agriculture and industry—benefiting small producers. In turn, the orthodox approach has made a convincing case that appropriately implemented adjustment policies not only are a necessary condition to the restoration of macroeconomic equilibrium but could also contribute marginally to economic growth and poverty alleviation, in the short run. Yet many observers feel, in retrospect, that the form of conditionality could have been significantly improved.

In 1993, the World Bank published a very influential report on the East Asian miracle (World Bank 1993). The report analysed the success elements of the high-performing Asian economies and argued that many of them were potentially transferable to other developing countries. In brief, these success elements consisted of (1) sound macroeconomic foundations and stable institutions aiming at a balanced budget and competitive exchange rates, (2) technocratic regimes and political stability that provided policy credibility and reduced uncertainty—an important factor for foreign investors, (3) an outward (export) orientation, (4) reliance on markets, (5) a more controversial set of industrial policies with selective government interventions often using ‘contests’ among firms as proxy to competition, (6) high rates of investment in building human capital, (7) high physical investment rates, (8) a process of technology acquisition consistent with dynamic comparative advantage and (9) a smooth demographic transition. In particular, the outward orientation, encouraging exports was applauded as a means of acquiring state of the art technology which in turn would trigger a ‘learning-by-doing’ and ‘learning-by-looking’ (e.g. reverse engineering) process that would lead to spill-over effects on human capital and positive externalities among firms within an industry and among industries.

The East Asian miracle also provided a convincing example of the essential importance of sound institutions (such as the balanced budget presidential decree in effect in Indonesia between 1967 and 1997) as preconditions to a sustainable process of growth with equity. The absence of institutions appropriate to a smooth transition from command to market economies in much of Eastern Europe and the fragility of existing institutions in much of sub-Saharan Africa provide painful counter-examples of the enormous human costs of a weak institutional framework.

The Asian financial crisis that wrought havoc to much of East and Southeast Asia in 1997 forced a critical re-examination of an international trade and financial system based on excessive trade and capital liberalisation and financial deregulation. The large increase in the incidence of poverty that followed in the wake of the crisis sensitised the development community to again focus on poverty reduction and improvements in the socio-economic welfare of vulnerable households as the overarching objective of development. Thus, at the end of the decade, the World Bank made it clear that poverty reduction—in its broadest sense—measured in terms of outcomes (e.g. health, education, employment, access to public goods and services and social capital) rather than inputs was the primary goal to strive for.

The decade of the 1990s was marked by a strong and lingering case of ‘aid fatigue’ evidenced by the absolute decline in net disbursements of official development assistance (ODA) after 1992. This downward trend resulted partially from the end of the Cold War but reflected also the strong faith in the operation of markets and scepticism regarding governments’ (both aid donors and recipients) involvement in productive sectors such as agriculture and industry. Fatigue was also influenced by the rising fear that foreign aid was generating aid dependency relationships in poor countries and, as such, would have the same type of negative incentive effects that welfare payments have on needy households whose recipients might be discouraged from job searching.

A related issue that was critically debated in the 1990s was that of the effectiveness of aid conditionality. First, given fungibility, is it possible to use aid to ‘buy’ good policies or even a sound programme of public (current and capital) expenditures from aid recipients? From the standpoint of the political economy of external aid, structural adjustment can be looked at as a bargaining process between bilateral and multilateral donors, on the one hand, and debtor governments, on the other. Both sides may have a vested interest in following soft rules in their lending and borrowing behaviour, respectively. This tends to foster and continue a dependency relationship that may well be fundamentally inconsistent with a viable long-term development strategy for the recipient countries (particularly in sub-Saharan Africa).

The conditionality debate continues to fuel a series of econometric studies of aid’s effectiveness based on international cross-sectional data. Perhaps the most influential one was that of Burnside and Dollar (2000) which concluded that aid can be a powerful tool for promoting growth and reducing poverty but only if it is granted to countries that are already helping themselves by following growth-enhancing policies. In contrast, Guillaumont and Chavet (2001) found that aid effectiveness depends on exogenous (mostly external) environmental factors such as the terms-of-trade trend, the extent of export instability and climatic shocks. Their results suggest that the worse the environment, the greater the need for aid and the higher its productivity. Hansen and Tarp (2001) argued that the Burnside–Dollar model did not stand up to standard specifications and that when account is taken of the dynamic nature of the aid–growth relationship, the Burnside–Dollar conclusion fails to emerge. Country-specific characteristics of aid recipient countries—aside from the policy regime followed by those countries—have a major impact on aid’s effectiveness which makes it difficult to generalise. It is noteworthy that these studies were criticised on econometric grounds.

7 Development Doctrine in the Most Recent Period (2000–2017)

The present period has witnessed some rich and fundamental contributions to development economics. Figure 3.7 outlines these contributions.

A strong case can be made that the most important contribution to development economics during this period has been the attempt to move it from a largely axiomatic and deductive discipline to a more experimental discipline.Footnote 9 Two separate but interrelated bodies of knowledge—one based on randomised controlled trials(RCTs) and natural experiments and the other based on insights from behavioural economics—have added a degree of realism in describing which projects work and how, in fact, actors (and particularly the poor) actually behave under different settings and circumstances. RCTs by relying on field trials captured the underlying settings while behavioural economics helped identify actual as opposed to presumed rational choice behaviour such as maximisation and ‘satisficing’. Behavioural economics, through theoretical, empirical and experimental investigations, made it possible to incorporate non-standard behaviour modes influencing the decision-making process such as procrastination, overweighting low probability outcomes, loss aversion and willingness to sacrifice return for the sake of fairness.

7.1 The Experimental Revolution: Randomised Controlled Trials

The recent two decades have been marked by what could almost be characterised as a paradigm shift in the prevailing methodology employed by development economics’ researchers.Footnote 10 Field experiments relying mainly on RCTs have become the overwhelming tool favoured by the research community.

RCTs as used in the evaluation of development effectiveness are a technique rather than a theory. As Duflo and Kremer (2003) argue “Any impact evaluation attempts to answer an essentially counterfactual question: how would individuals who participated in the program have fared in the absence of the program?” One of the best early example of impact analysis is the quasi-experimental design used in evaluating the redistributive PROGRESA programme in Mexico that relied on the selection of target villages (receiving benefits) and control villages (not presently receiving benefits but eligible for benefits in future rounds). Programme effects are estimated by comparing treated individuals or communities to control individuals or communities. There is no question that this new methodology has revolutionised the evaluation of social programmes by providing a more scientific base for the recommendations comparable to the design of drug and medical trials. The Handbook of Field Experiments (Duflo and Banerjee 2017) provides a large amount of useful evidence derived from field experiments on a variety of development issues such as in health on how to incentivise providers; in education on how to organise the classroom and incentivise teachers; in credit on repayment conditions and ratings of customers; and on index insurance on how to observe yields and overcome time inconsistencies.

The leading institution in conducting RCTs is the Abdul LatifJameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL) at MIT that, by 2017, had over 840 ongoing and completed randomised evaluations in 80 countries. Aid donors, and especially the World Bank, became enthusiastic supporters of RCTs because this technology could determine whether a specific project worked and was successful or not.

After an initial period of euphoria, such early claims that RCTs were (1) ‘the gold standard’; (2) the only valid methodology in development economics; (3) occupied “a special place in the hierarchy of evidence, namely at the top” (Imbens 2010); and (4) that “the World Bank is finally embracing science” (The Lancet 2004 editorial)Footnote 11 were subjected to critical scrutiny. The essence of the critique was directed at the limitation of this approach in that a given RCT only provides a precise and robust answer to a very narrow question, that is, “what is the effect of a specific program on a specific date within a specific context?” By definition, RCTs cannot address a whole host of important dynamic macroeconomic issues, such as structural transformation, and climate change.

Given the extreme influence enjoyed by the randomised field trial approach among the development community and its present impact on the substance of development economics, it is important to review and analyse in a constructive way the criticisms that have been expressed.

The latter can be grouped under four interrelated headings: (1) do RCTs contribute to uncover the underlying mechanisms through which an intervention affects the desired development outcome? (2) can the lessons learned from one or even multiple RCT settings be generalised to other different settings? (3) how serious a shortcoming is it that the RCTs do not address general equilibrium effects? and (4) does the randomised trials’ approach give rise to ethical issues?

The first question goes to the heart of the development methodology and doctrine. In its pure form, the purpose of an RCT is “not to understand the underlying structure of the system of relationships generating the outcomes, only the statistical outcome impact of certain policy treatments” (Mookherjee 2005). Relying on reduced form relations without explicitly identifying and presenting the structural (and behavioural) model yielding the reduced form allows the researchers to by-pass what some would consider a fundamental prior step, namely, the theoretical foundations of the tested hypotheses. Controlled experiments per se do not enlighten us on the underlying mechanisms generating the outcomes. One of the strongest critics of RCTs, Deaton (2010, p. 426), writes that “Project evaluations, whether using randomised controlled trials or nonexperimental methods are unlikely to disclose the secrets of development, unless guided by theory”, and “Learning about theory, or mechanisms, requires that the investigation be targeted toward that theory, toward why something works, not whether it works” (p. 442).

RCTs appear to have largely replaced structural and behavioural models in the tool kit of development economists. The potential strength of those latter models is that they capture explicitly the underlying structure and behaviour of the agents and rely on the prevailing body of theory. It seems that blending RCTs and structural models might be quite fruitful. Greater use of theory could help explain and clarify the (causal) mechanisms underlying findings generated by controlled experiments and permit a wider range of policy assessments (Mookherjee 2005). In fact Heckman (2010) makes a convincing case that a bridge can and should be built between the two approaches. As he points out: “The two approaches can be reconciled by noting that for many policy questions, it is not necessary to identify fully specified models to answer a range of policy questions. It is often sufficient to identify policy invariant combinations of structural parameters” (p. 368).

The second main criticism directed at the RCT approach is that of the generalisability and transferability of the specific findings in a given setting at a given time to other settings. Basu (2013) argues that we cannot assume that a programme that worked in a specific setting (location) and time context will be effective in a different setting or even the same location tomorrow.Footnote 12 As the underlying conditions change, so might the effectiveness of a policy intervention. There are technical and statistical issues that limit if not preclude generalisability and external validity. A well-designed RCT can provide credible estimates of the average treatment effect (ATE). The latter, in turn, can be influenced by outliers and it is “precisely the few outliers that make or break a programme. In view of these difficulties, we suspect that a large fraction of RCTs in development and health economics are unreliable” (Deaton and Cartwright 2016). Hence, if the distribution of outcomes of a treatment in the population of a given trial is significantly different from what would have been the distribution of outcomes in another setting, then the transferability of the findings of the original RCT to another setting is questionable.

J-PAL is conscious of this issue and refers to it as the ‘generalisability puzzle’. It also recognises the essential need for causal and structural models as discussed previously and the need for integrating different types of evidence, including results from the rising number of randomised evaluations including apparently running the same treatment in different contexts (Bates and Glennerster 2017).Footnote 13 They conclude that “if researchers and policy makers continue to view results of impact evaluations as a black box and fail to focus on mechanisms, the movement toward evidence-based policy making will fall short of its potential for improving people’s lives” (Bates and Glennerster 2017, p. 12).

The third potential shortcoming of RCTs is that, as such, they ignore the indirect effects of a policy intervention. These general equilibrium effects can in certain cases be significant and even dominate the direct effects. In most instances these indirect effects are likely to be positive and to augment the direct effects in a positive direction, but it is possible to conceive of some scenarios where these general equilibrium effects would have some negative consequences that would reduce or even negate the initial benefits of a given intervention. The solution to this dilemma is for users of the randomised trials approach to attempt to estimate the indirect impact of an intervention with the help of an appropriately linked CGE model.Footnote 14

Finally, following appropriate protocols, being aware of the possible negative impact of some groups excluded from the treatment groups and designing some compensation scheme can resolve most ethical issues inherent to RCTs. One example which also illustrates how behavioural economics can be used in aid is the classic “lentils and a plate for vaccination” by Banerjee et al. (2010) which revealed how a small incentive in rural India could encourage vaccination. By providing the same sweetener to the control group, some of the foregone benefits of vaccination could be partially compensated.

7.2 The Role of Institutions and the Political Economy of Development

A major characteristic of the approach to development issues in the present period is the multidisciplinary broadening of what had previously been a narrower economic base. The lens through which development researchers and practitioners explore development issues, now, increasingly incorporates concepts from other disciplines such as psychology, as discussed earlier, sociology and political science. Two good examples of fruitful collaboration between economists and political scientists are on the role of institutions in development and the political economy of development, respectively.

In an extremely influential article, Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2001) made a strong case that development depends on institutional quality. They selected an instrumental variable, colonial settler mortality, that affects institutions exogenously but not income directly and were able to explain inter-country differences in per capita income as a function of predicted quality of institutions. Their hypothesis is that mortality rates among early European settlers in each colony determined whether they would decide to establish resource-extractive or plundering institutions or to settle and build European institutions and, in particular, those protecting property rights. However, as Bardhan (2005) has argued, there are other types of institutions that matter for development, such as participatory and accountability institutions, and institutions that facilitate investment coordination.

Subsequently, Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) make a compelling and convincing case, based on a myriad of historical episodes worldwide, that growth (and, more generally, development) can only be sustained in the long run if it is anchored on and supported by inclusive political and economic institutions. Central to their theory “is the link between inclusive and political institutions and prosperity. Inclusive economic institutions that enforce property rights, create a level playing field, and encourage investments in new technologies and skills are more conducive to economic growth than extractive economic institutions that are structured to extract resources from the many by the few and that fail to protect property rights or provide incentives for economic activity” (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012, p. 430).

Institutions and policies might be viewed as tools for moving an economy out of one (bad) equilibrium into another (good) one. In a dynamic sense this process corresponds to a phase transition. If economic development is conceived as one of phase transitions, it carries far-reaching implications for the role of government. Institutions must be established and policies designed and implemented that facilitate the phase transition. One implication is that the emphasis on temporary, one-time interventions is likely to be much greater and if successful will not have to be repeated. If and once the new (good) equilibrium is reached, it is presumably sustainable within the new institutional and policy framework. It would be like jump-starting a car whose battery had run down.

The political economy of development was greatly influenced by the contributions of a group of Harvard economists starting in the 1990s. A key contribution was that of Alesina and Rodrik (1994) who argued that the greater the inequality of wealth and income, the higher the rate of taxation and the lower subsequent growth. The new political economy theories linking greater inequality to reduced growth operate through the following channels: (1) unproductive rent-seeking activities that reduce the security of property; (2) the diffusion of political and social instability leading to greater uncertainty and lower investment; (3) redistributive policies encouraged by income inequality that impose disincentives on the rich to invest and accumulate resources; (4) imperfect credit markets resulting in under-investment by the poor—particularly in human capital; and (5) a relatively small income share accruing to the middle class—implying greater inequality—has a strong positive effect on fertility which, in turn, has a significant and negative impact on growth (see Thorbecke and Charumilind 2002, for a detailed discussion of how each of these channels affects growth).Footnote 15

7.3 Poverty Traps and Multiple Equilibria

While the most innovative contributions to the concept of poverty traps (which at that time were referred to as vicious circles of poverty) originated in the decade of the 1960s and are described in an earlier section, the increasing availability of time series allowed for a better understanding of poverty traps within a dynamiccontext. A poverty trap is a self-reinforcing mechanism which causes poverty to persist (Azariadis and Stachurski 2005). There are many different types and causes of poverty traps such as (1) under-nutrition resulting in low physical activity and productivity; (2) under-investment in education and skill acquisition; (3) geographical remoteness; (4) social exclusion and marginalisation; and (5) lack of assets sealing some household out of the capital market. Access to more diversified and longer panel data on household living standards has made it possible to distinguish better between chronic (structural) poverty and transitory poverty (Carter and Barrett 2006). It has also helped in identifying the root causes of those traps and measures to combat them.

A theoretical construct that is presently in vogue and that appears promising in exploring poverty traps, how to escape them and a variety of other issues in development economics is that of multiple equilibria. If an economy is stuck in a bad equilibrium (a poverty trap), moving it to a good equilibrium would allow it to escape from the trap. In a more general sense Ray (2000) provides a vivid example drawn from the Rosenstein-Rodan (1943) Big Push notion and the Hirschman (1958) backward and forward linkages concept. These pioneers argued that economic development could be thought of as a massive coordination failure, in which several investments do not occur simply because of the absence of other complementary investments and similarly, these latter investments are not forthcoming because the former are missing. In the same vein Sachs (2006) argues that a ‘Big Push’ in the amount and allocation of foreign aid would end poverty in the developing world.

7.4 The Interrelationship Among Growth, Inequality and Poverty