Abstract

This chapter deals with income inequality in developing countries. It gives a historical overview on how income inequality has been addressed in developing countries and discusses contemporary issues of income inequality, especially in the context of growing globalization. Globalization and especially financialization and to a certain extent skills based technical change, have been important exogenous drivers of inequality. These drivers have in various cases strengthened existing patterns of inequality through a stubbornly high wealth inequality and through intergenerational transfers of inequality due to skewed access to higher-level education. The adverse effect of financial and trade globalization, on income inequality during the past three decades have been exacerbated by national policies that had a negative impact on income distribution. Monetary policies that emphasized price stability over growth, labour market policies that weakened bargaining position of labour vis-à-vis employers, and fiscal policies that prioritized fiscal consolidation at the expense of benefits and progressive taxation, all contributed to increasing income inequality. However, national policies, including a strengthening of institutions to deal with inequality can play an important role on reducing income inequality. Several countries have managed to use fiscal policies to mitigate a high primary income inequality down to lower levels of secondary and tertiary inequality. Additionally, the right mix of macroeconomic, fiscal, labour market and social policies (policy coherence) can reverse the rising trend in income inequality.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Data on household income inequality show a rising trend from the early 1990s to the early 2010sFootnote 1 in a majority of countries. In a sample of 116 countries, household income inequality, as measured by the Gini index, increased by 9 per cent for the group of high-incomeFootnote 2 countries and by 11 per cent for low and middle-income countries (UNDP 2013). Thus, inequality rose faster in developing countries than in developed countries.

This chapter deals with income inequality in developing countries.Footnote 3 It first gives a historical overview on how income inequality has been addressed in developing countries. Section 2 discusses contemporary issues of income inequality, especially in the context of growing globalization. Section 3 pays special attention to the vexed issue of income inequality and economic growth. In order to get a better understanding of income inequality issues and policy solutions thereto, Sect. 4 discusses drivers of income inequality. It distinguishes between functional income inequality (the distribution between labour and capital income) and various forms of household income distribution as well between exogenous (international) drivers and endogenous (national) drivers of income inequality. Exogenous drivers such as trade and financial globalization as well as technological change are further elaborated. Section 5 gives evidence of growing income inequality under globalization focusing on both factor income inequality and household income inequality. Section 6 concentrates on endogenous drivers of inequality and discusses how national policies can reduce income inequality. Section 7 concludes the chapter.

2 Income Distribution Issues in Development Economics: A Brief History

2.1 How Distribution Issues Have Been Addressed in Development Economics

In the first two decades after the Second World War, the issue of income inequality within developing countries received little attention. Development economics rather emphasized developing countries catching up with developed countries. For example, the background document to the first Development Decade of the United Nations (UN) (1960–1970), in its discussing poverty, adhered to the idea of economic growth trickling down and was silent on reducing income inequality.Footnote 4

In the early 1970s, however, more and more scholars and activists started to voice concern about growing inequality and enduring poverty, especially those from Latin American countries where progress coincided with high or growing income inequality. The Prebisch report in 1970 advocated therefore a reduction of income inequality in Latin America. It argued also that reducing inequality would not hamper growth and economic progress (Prebisch 1970). It showed that more equal income inequality could lead to a more balanced growth, through which poverty could reduce faster. The International Labour Organization (ILO) carried out, in cooperation with development institutes in developing and developed countries, a number of targeted country analyses on employment and inequality and did put the issue of unacceptable high levels of inequality on the international agenda. The ideas gathered by the ILO and by research groups in various countries resulted in 1974 in the publication of Redistribution from Growth by the Institute of Development Studies in Sussex, in cooperation with the World Bank (Chenery et al. 1974). This publication documented for several countries growing inequality and emphasized practical redistribution policies. Adelman (1979) brought the idea of redistribution from growth further to Redistribution Before Growth, based on successful development patterns in Taiwan and Korea. She argued that redistributing factors of production (land, secondary and higher education, investment capital) before these factors would become scarce in a strong growth phase (and thus commanding higher factor rewards such as wages and prices) would be a superior way to achieve a more equal income distribution during the course of development.

The attention to greater equality in the mid-1970s also led to the so-called basic needs approach to development, partly based on the first five-year development plans in India after independence. It became a focus in various development institutes and international organizations. The logic was as follows: If the satisfaction of basic needs would be a main objective of development, then logically more attention to redistribution is warranted in order to arrive faster at providing basic needs (Hopkins and van der Hoeven 1983). This approach, however, was not entirely accepted. According to some scholars, the basic needs approach focused too much on the poorest developing countries and gave too little attention to international measures to foster national economic growth (van der Hoeven 1988). Basic needs were thus interpreted as a distraction from the 1970s debate on a New International Economic Order (NIEO) that envisaged reforms in the international relations so that developing countries could grow faster. This fear was actually fed by the fact that the World Bank became interested in the basic needs approach; however, more as a social planning instrument without redistributive elements, than as a strategy for large structural changes within countries and between countries.

However, while these discussions were going on, structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) started, especially in the International Financial Institutions to dominate development thinking and financing. After two oil crises in the 1970s and an increase in foreign debt in many developing countries—caused by the abundance of petrodollars on the world market—and after the debt crisis of Mexico in 1982, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) introduced SAPs. Their focus was on budgetary cuts, liberalization of markets and active promotion of exports, aiming at stimulating growth and at strengthening capacity in developing countries to repay debts in foreign currency (Addison 2002). Attention to social problems and domestic income inequality moved to the background. Late 1980s, however, saw a countermovement. For critics saw the SAPs, because of their liberal economic policy, became a major cause for increasing inequality and other social problems, especially in those countries that were obliged to take part in the SAP. The criticism of the structural adjustment programmes rose, not only from a social angle but also more and more from an economic angle, as the programmes often did not lead to accelerated growth and reduction in debt. (A special programme for debt forgiveness in poorer countries—heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC)—had to therefore also be set up in the 1990s.) It would take until the middle of the 1990s until more social objectives of development cooperation gained traction again.

In the early 1990s the UN organized a number of World Summits on development issues. Since Cold War issues no longer dominated the discussions in the UN. Amongst these was the Social Summit in Copenhagen in 1995 (World Summit for Social Development), which dealt with the problems of, and gave policy recommendations for, poverty reduction, employment and social inclusion. The Social Summit contained explicit recommendations for the reduction of political, legal, economic and social factors that promoted or maintained inequality in income.

The results of the renewed attention to social issues led to preparations for the UN Millennium Summit in 2000 and to the subsequent formulation of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), in which a 50 per cent reduction of poverty and improving several social targets at the global level were among the eight goals. That attention to national income inequality in that context was warranted can best be underscored by a thought experiment on inequality on raising the question what if all developing countries would have in the year 2000 an inequality level, which was the lowest they had seen since the Second World War. It showed that the number of poor people in developing countries in 2000 could have been one-third less if countries would have a level of inequality equal to that what they would have had in the past. A second thought experiment added another fact, namely that a country with moderate inequality would grow faster than a country with greater inequality. Under this second thought experiment the number of poor would have been reduced by almost 40 per cent (Fig. 10.1). Yet the MDGs did not contain any reference to reducing income inequality. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted in 2015 do, however, contain goal 10 to reduce income inequality, but as the discussion in Box 10.2 shows, the formulation of goal 10 and the related indicators is found wanting.

Population in poverty in the year 2000 according to actual and hypothetical best-income distribution scenariosSource: Compiled from Luebker 2002

At the end of the 1990s, the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER) started a large research programme on inequality, growth, poverty and globalization. Globalization is characterized by greater integration in terms of trade and capital flows, made possible by new technologies but more so by international conventions and agreements that liberalized the rules governing external markets, as explained in the report of the World Commission on the Social Dimensions of Globalization (ILO 2004).

One of the findings of the UNU-WIDER programme was that too high-income inequality hampers a kick off of growth, but also too little inequality, as happened in the former communist countries in Eastern Europe. The project looked first at, what it labelled, the old explanatory factors of inequality (land inequality, poor education, poor infrastructure, urban bias) and found that, while these still explained the level of inequality, these could not explain well the rise in inequality. The main causes of the increase in national income inequality were the liberalization of trade and especially of capital markets, very much associated with globalization, the significantly increased financialization of national economies and of international relations, technological change and the growing limitations of labour market institutions that had led to greater inequality between unskilled and skilled workers (Cornia 2004, Shorrocks and van der Hoeven 2004). Despite these and various other analyses, the MDGs, as mentioned earlier, did not include reducing national income disparity in the targets for poverty reduction, and, for that matter, did not include reducing national inequality in other targets.

In the early years of the twenty-first century, some major developing countries, now more appropriately called ‘emerging countries’, showed strong growth in national income. These countries are catching up (Nayyar 2013). Also some poorer countries showed faster growth for the first time. However, income inequality rose in many countries, developing countries, emerging countries and developed countries alike. A number of countries in Latin America showed some decrease in income inequality, but this was not enough to get them out of the leading group of countries with the greatest income inequality in the world.

Halfway through the first decade of the twenty-first century, a large number of reports from, among others, the UN, the World Bank, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and ILO appeared which all called for a reduction of rising or high-income inequality, based on extensive research and data collections in this field. The validity of the Kuznets curve (which argued that during a process of development, income inequality would rise and thereafter would decline, and hence there would be no need for special attention) was rejected and valid arguments were put forward that a more equal distribution of income and assets did not have to lead to a decrease in economic growth.

After the 2007–2008 financial crisis, even the more traditional financial and economic circles sounded the alarm bell, fearing that large and rising income inequalities could affect the foundations of the free-market system. Piketty’s book Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Piketty 2014) was well received (see also Box 10.1). Globalization, at least the unrestricted globalization that we see now, and income equality are clearly at odds with each other (see also Gunther and van der Hoeven 2004; van der Hoeven 2011a, b; Vos 2011; Bourguignon 2015). Research on the effects of the 2007–2008 financial crisis shows that the poorer segments in the developed countries face a triple whammy: they did not profit from globalization, they were hardest hit in terms of unemployment and are now bearing the consequences of fiscal tightening, following the massive stimulus and bank bailouts (Table 10.1). The situation for developing countries though is more complex. The growth path of the emerging developing economies shows similar movements as that of developed countries, but of less intensity, and these economies were thus less affected by the crisis. However, except for some Latin American countries, the growing inequality that was building up or being reinforced is not yet being halted, and also wage shares in most emerging market economies are still declining, with a negative effect on domestic demand. The poorer developing countries, mainly in Africa, were less affected as their banking system was less developed, but still suffered from slower exports proceeds, remittances and lower aid levels.

3 Income Inequality and Growth

Analyses from the 1950s into the 1970s emphasized a possible trade-offs between growth and income distribution. This derived in part from an interpretation, by some labelled as an erroneous, of Kuznets’s famous ‘inverted-U hypothesis’, which postulated that inequality would rise in the initial phases of development, then decline after some crucial level was reached and hence policy action to reduce inequality was unwarranted.Footnote 5 Growth theories were cited in support of the hypothesis, such as the Lewis model of “economic development with unlimited supplies of labour” (Lewis 1954).

After a brief period in the 1970s in which some policy attention was given to redistribution without hampering growth, the policy arena became dominated by neoliberalism, in particular the Washington Consensus of the late 1980s. This Consensus held that growth itself would be the vehicle for poverty reduction, to be achieved through ‘trickle-down’ mechanisms, which themselves were not always clearly specified and with no specific role for income (re) distribution (van der Hoeven and Saget 2004).

Because poverty and inequality have a transitional component, induced by external shocks such as business cycles and price instability, they can be affected by short-term macro-policies as well as by long-term growth. Particularly controversial are the possible adverse effects on poverty of the already mentioned SAPs. In response to the controversy over the effects of adjustment on the poor, the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) proposed ‘social safety nets’ and ‘social funds’ in some countries, to target adjustment-induced poverty. These programmes were typically designed for a limited period. An evaluation of social safety nets suggests that these programmes, sometimes financed by multilateral lending, had some positive impact on what might be called ‘adjustment losers’, but it did not reduce inequality or necessarily reach the poor.Footnote 6

The perceived ineffectiveness of redistributive measures under the Washington Consensus led some to advocate targeting public expenditure to the poor, and judging effectiveness by the accuracy of that targeting. However, the targeting of expenditures in developing countries has been fraught with difficulty. Sen (1995) argued against targeting public spending for a number of reasons: (1) information asymmetries reduce the effectiveness of targeting in the presence of ‘cheating’, (2) the prospect of losing targeted subsidies may reduce beneficiaries’ economic activity, (3) targeting may undermine the poor’s self-respect and (4) the sustainability of targeted programmes is doubtful, as the potential beneficiaries are politically weak. To Sen’s list, one can add the formidable measurement problem of identifying who qualifies. Targeting public spending is more likely to be effective where the poor form a small proportion of the population, that is, if poverty is not a major problem. For countries in which poverty is widespread, the administrative costs of identification, monitoring and delivery of programmes may outweigh benefits.

In the early 1990s a strand of theory invoked the so-called political economy arguments in relation to inequality and, by implication, poverty (Alesina and Rodrik 1994). This analysis predicted a negative relationship between income inequality and growth on the grounds that higher initial inequality would (1) lead to increased public expenditure because it prompts a demand for redistributive policies and (2) incite political instability that undermines growth. This excursion into political science is nonetheless somewhat dubious. For example, it is not at all clear how a society with the power relationships to generate inequality would, at the same time, produce an underclass with the political clout to force redistributive policies upon a government.

On somewhat firmer analytical ground is the argument that inequality hinders growth through imperfect capital markets to which the poor have limited access (Aghion et al. 1999). In other words, if capital markets discriminate against the poor, potentially profitable activities by the poor are constrained by lack of credit. However, the imperfect capital markets argument has practical limitations, in that it presumes the poor to be self-employed or to have the option to become so. While this may apply to a portion of the households in poverty, empirical evidence suggests that during the 1990s those in the lowest income quintile, in Latin America at least and perhaps elsewhere, were increasingly in wage employment. Indeed, the idea that most low-income wage earners could escape poverty through self-employment challenges the imagination as well as historical trends.

Towards the end of the 1990s, a number of studies challenged both the neoliberal analysis and the earlier view of a trade-off between growth and equity (Ferreira 1999; Milanovic 1999; van der Hoeven 2002; Weeks 1997). In particular, doubt fell upon the sanguine view that orthodox macro-policies were, by their nature, inequality- and poverty-reducing. On the one hand, mainstream literature, with its emphasis on the efficiency of markets, tended to view inequality and poverty as accidental or occasional outcomes of a deregulated growth process. On the other hand, the persistence and severity of poverty in many, if not most, developing countries fuelled periodic arguments for their alleviation. The shifts in emphasis in the literature reflect the difficulty of reconciling these two perspectives.

Focusing specifically on the effects of inequality and growth, Cornia (2004) found a distinct non-linear relationship between initial income inequality and economic growth in subsequent periods. Figure 10.2, based on these results, shows that too low inequality is bad for growth (leading to a proclivity for free-riding and high supervision costs), but that too high inequality levels can also have serious negative consequences. Income inequality in most developing countries is in the high range.

Inequality and growth

Source: Cornia 2004, p. 45

Birdsall (2005) therefore argues that income inequality in developing countries affects growth for at least three instrumental reasons:

-

Where markets are underdeveloped, inequality inhibits growth through economic mechanisms.

-

Where institutions of government are weak, inequality exacerbates problems in creating and maintaining accountable government, increasing the probability of economic and social policies that inhibit growth and poverty reduction.

-

Where social institutions are fragile, inequality further discourages the civic and social life that girds the effective collective decision-making necessary for the functioning of healthy societies.

These and various other arguments why initial high-income inequality might hamper growth are depicted in Fig. 10.3. Nissanke and Thorbecke (2005, 2006) provide a useful discussion.

High initial income inequality and economic growth: Illustrative causal relation patterns

Source: Nissanke and Thorbecke 2005, Figure 1

A recent survey of the literature in a staff note of the IMF (Ostry et al. 2014) concludes that:

the statistical evidence generally supports the view that inequality impedes growth, at least over the medium term. In a sequence that mirrors intellectual fashions on the empirics of growth, researchers have looked at rates of growth over long periods of time (for example, Persson and Tabellini 1996; Perotti 1996; Alesina and Rodrik 1994), the level of income across countries (Easterly 2007), and the duration of growth spells (Berg et al. 2012), and have found that inequality is associated with slower and less durable growth. The few exceptions (Forbes 2000; Banerjee and Duflo 2003) tend to pick up ambiguous short-run correlations. (Aghion et al. 1999; Halter et al. 2010)

The growing consensus is thus that countries with an ‘initial condition’ of relatively egalitarian distribution of assets and income tend to grow faster than countries with high initial inequality. This is an extremely important conclusion, because it means that reducing inequality strikes a double blow against poverty. On the one hand, a growth path characterized by greater equality at the margin directly benefits the poor in the short run. On the other hand, the resulting decrease in inequality creates in each period an ‘initial condition’ for a future that is growth enhancing. Hence, any growth path that reduces inequality reduces poverty through redistribution and via ‘trickle down’.

As discussed, a nowadays common accepted position is that low-income inequality does not hamper growth, and under reasonable assumptions can even result in higher growth. However, in order to achieve low initial income inequality in a given growth process, a relevant policy question is whether redistributive measures to achieve low-income inequality have a neutral effect on growth or not. This has been less clear in the literature. Some authors who argue that low initial income inequality will result in higher growth, base their conclusion just on the observation that high initial income inequality will lead to redistributive measures which will hamper growth (Alesina and Perotti 1996; Alesina and Rodrik 1994). Ostry et al. (2014, p. 10) report however that:

the empirical studies on the relation between redistribution and growth are also somewhat divided. When studies look at presumptive indicators of redistribution (such as taxes or government spending), they tend to suggest that more redistribution is detrimental to growth. On the revenue side, there is surprisingly little evidence that increases in tax rates impede medium-to-long-run economic growth. Overall, it seems hard to improve on the conclusions of Tanzi and Zee (1997), who find some general indication that the relationship between growth and the level of total taxes or of income taxes is negative but that this relationship is not robust and is sensitive to model specification. With respect to spending, Lindert (2004) sees something of a “free lunch” paradox in that some categories of public spending that are redistributive have no apparent adverse impact on growth (for example, spending on health and education, or tax-financed infrastructure spending).

Ostry et al. (2014) on the basis of an extended statistical analysis concludes:

we find no evidence that redistribution is harmful. The data tend to reject the Okun assumption that there is in general a trade-off between redistribution and growth. On the contrary, on average—because with these regressions we are looking only at what happens on average in the sample—redistribution is overall pro-growth, taking into account its effects on inequality. And these results do not seem to depend on the levels of inequality or redistribution. Moreover, they hold even in the restrictive sample, which makes relatively conservative assumptions about which data to include in the regression, as well as in the full sample, which makes use of all available data.

4 Drivers of Income Inequality

4.1 General

What are the drivers of inequality? In order to answer that question one must first define income inequality more precisely. Until now income inequality within countries was discussed one may say should we not have a more cosmopolitan approach, especially given the strong growth of several emerging economies, and rather look at inequality in the world? Several authors have done so in detail, for example, Milanovic (2012) and van Bergeijk (2013). UNDP (2013) based on Milanovic (2012) has demonstrated what this entails (Fig. 10.4).

Gini index of global income inequality

Source: UNDP 2013, Box 3.1

If we treat each country as a unit (Concept 1), average incomes across countries have actually become more unequal until 2000 with a slight decline thereafter. However, if countries are weighted only by the size of the population (Concept 2), incomes across the world become more equal. But if we take incomes of all households individually into account (Concept 3 for which much less data are available), the Gini index of global income inequality is around 0.7, much higher than the level of income inequality found within any individual country. Despite the convergence in world income of some big emerging countries, rising income inequalities within these countries resulted in overall global inequality, declining only slightly after some increase during the globalization era from the mid-1980s to the early 2000s (Milanovic 2012).Footnote 7 It remains therefore important to consider national income inequality.

What are the drivers of inequality? In order to answer that question we must first define income inequality more precisely. The classical economists paid attention mainly to the distribution of income between labour and capital, the main factors of production. This type of inequality is therefore called the factor income or functional inequality. The distinction between labour and capital income drove the great classical debates for many years. In the post-Second World War period, however, less attention was given to this type of inequality, as neoclassical production functions often assumed a constant capital share under the assumption that wage increases follow productivity increases. Attention shifted to personal income or household income distribution.

One can interpret household income distribution in three ways (van der Hoeven 2011):

-

Primary income distribution: the distribution of household incomes, consisting of the (sometimes cumulated) different factor incomes in each household, before taxes and subsidies as determined by markets and market institutions.

-

Secondary income distribution: the distribution of household incomes after deduction of taxes and inclusion of transfer payments (i.e. as determined by fiscal policies).

-

Tertiary income distribution: the distribution of household incomes when imputed benefits from public expenditure are added to household income after taxes and subsidies. This interpretation of household income is particularly relevant for developing countries as different services and government services are often provided for free or below market prices.

Most policy discussions on inequality though focus on secondary household income distribution (take-home pay, rents, interest earnings and profits after taxes).

Over the last ten years attention is shifting back to factor income distribution.Footnote 8 Daudey and Garcia-Penalosa (2007) argue that the distribution of personal or household income depends on three factors: the distribution of labour endowments, the distribution of capital endowments and the way in which aggregate output is shared between the two production factors. The factor distribution of income is a statistically significant determinant of the personal distribution of incomeFootnote 9: a larger labour share is statistically associated with a lower Gini index of personal incomes. It is therefore important to also (re)consider the factor distribution of income.

The focus on factor income inequality points to the importance of better understanding the changing position of labour in the production process in order to correctly interpret inequality trends, as labour has been losing ground relative to capital over the past 20 years (ILO 2011). Furthermore, experience has shown that it is not possible to reduce primary household income inequality without addressing how incomes are generated in the production process and how this affects factor income inequality (van der Hoeven 2011). Atkinson (2009) argues convincingly that there are at least three reasons to pay again greater attention to factor income distribution:

-

to make a link between incomes at the macroeconomic level (national accounts) and incomes at the level of the household;

-

to help understand inequality in the personal distribution of income; and

-

to address the social justice concerns with the fairness of different returns to different sources of income.

Glyn (2009) argues that factor income distribution matters to people for at least two reasons. Firstly, despite broader access to capital among households, wealth, and especially high-yielding wealth, is still extremely unevenly distributed (see also Piketty 2014 and Box 10.1). Therefore redistribution from labour to property still has a significant effect in raising household income inequality. Secondly, the fact that profits may be rising much faster than wages conflicts with widely held views of social justice and fairness.

More recently Trapp (2015) has argued that dynamics in the factor income distribution are of particular relevance for developing countries, especially in their effort to fight poverty. Regressive redistribution of factors and their remuneration will be felt strongly in these countries due to weak social safety nets and limited access to capital by the poor. The main asset of the poor certainly is labour. As such, the labour income share can serve as an indicator in designing policies for social protection and tax systems as these usually target the factor income distribution (minimum wage policies, tax concessions for investments, etc.).

It is therefore important to be more explicit about the drivers of factor income distribution, as well as the drivers of primary, secondary and tertiary household income distributions and the relation between these different types of inequality.

There are many drivers that affect the different types of income distribution. One can distinguish between drivers that are largely exogenous (outside the purview of domestic policy) and endogenous drivers (i.e. drivers that are mainly determined by domestic policy). However, a clear line is difficult to draw because even drivers that may at first sight appear to be exogenous or autonomous are often the outcome of policy decisions in the past or the outcome of a domestic political decision to create international institutions (e.g. the creation of World Trade Organization (WTO) to establish trade liberalization or the decision to invest in technical progress). With increased globalization, exogenous drivers gain in importance. As a consequence more is expected from national policy drivers to counteract the effect of the more exogenous drivers. Table 10.2 shows the interactions between the major drivers and the various types of income distribution.

The crosses in the table indicate where the effects of these various drivers are the strongest. We see that exogenous factors (globalization) affect mainly factor income and primary distribution (upper left quadrant of Table 10.2), while endogenous drivers affect both factor income and various types of household income distributions (lower left- and right-hand quadrants).

Many aspects of globalization can be seen as drivers of income inequality, especially of factor and of primary household income inequality (van der Hoeven 2011). Traditionally, most attention has been given to the effects of trade and trade openness on income inequality, but more recently financialization and technical change (particularly in relation to its effect on wage differentials) have also been the focus of much attention. The impact of these globalization drivers on income inequality depends however also on national macroeconomic and labour market policies, which can either counteract or intensify their effects.

4.2 Trade Globalization and Investment Liberalization

The leading framework for understanding the possible link between trade and inequality until the 1990s was the Heckscher-Ohlin (HO) model. This model predicts that countries export goods that use intensively the factor with which they are most abundantly supplied and that therefore trade increases the real return to the factor that is relatively abundant in each country, lowering the real return to the other factor. According to the HO model, inequality in developing countries that are well endowed with unskilled labour should have declined with trade as the real returns to unskilled labour rises (Harrison et al. 2011). However, this is contradicted by evidence of rising inequality in developing countries in a period of rapid globalization. An additional problem for the HO theory has been widespread evidence of within-industry increases in demand for skilled workers (UNCTAD 2012).

An alternative—and currently more credited—framework to explain the relation between globalization and inequality trends looks at how technological change increased the demand of skilled workers (Harrison et al. 2011). Other factors that have been cited by economists include changes in labour market institutions, leading to the weakening of labour collective action platforms such as unions and the declining real value of minimum wages; differential access to schooling; and immigration. Most labour and trade economists were sceptical of assigning too great an importance to trade-based explanations for the increase in inequality (Freeman 2004).

Seguino (2007) suggests that investment liberalization, instead of, as frequently assumed, raising living standards, could lead to slower wage growth. Investment liberalization leading to increased firm mobility may be read by workers as a credible threat that firms are able relocate in the event of unacceptably strong wage demands on the part of labour. The increase in firm bargaining power, even if not acted on via firm relocation, can lead to slower wage growth. This in turn can reduce pressure on firms to innovate or adopt new technologies, leading to slower productivity growth than in an era of regulated foreign direct investment (FDI) flows.

4.3 Financial Globalization

One of the reasons explaining that, despite the expectations of declining inequality according to the HO model, inequality in developing countries instead increased, is the fact that trade openness was often combined with capital openness (financial liberalization). According to Taylor (2004), the opening of the capital account, without compensating national measures, caused the real exchange rate to rise in many countries. This, in turn, shifted aggregate demand towards imports, and led to a restructuring of production, (thus reducing the absorption of unskilled labour), increasing informalization and raising wage inequality. The opening of the capital account is only one of the many (interrelated) aspects of a global process, often called financialization, which also includes various forms of financial deregulation. Developing countries have been especially vulnerable to financial volatility (Ghosh 2011). For instance, financial deregulation in some countries, notably the United States, has had a destabilizing effect on developing countries that otherwise had fairly prudent financial management framework. This is because international capital flows largely respond to the ‘manics’ and ‘panics’ of financial markets, in addition to economic fundamentals (Freeman 2010).

Financialization has had four important effects on the bargaining position of labour. Firstly, as a result of financialization, firms and wealth holders have gained more options for investing. Secondly, they have gained mobility in terms of the geographical location within countries and between countries as well as in terms of the content of investment. Thirdly, financialization has empowered shareholders relative to workers by putting additional constraints on firms to create immediate profits, while the development of a market for corporate control has aligned management’s interest to that of shareholders (Stockhammer 2013). ILO (2008a, b) observes that “financial globalization has led to a depression of the share of wages in GDP”. A fourth mechanism by which financial liberalization has led to slow wage growth is the effect on countries’ monetary policy. Wealth holders fear inflation and thus pressure governments to keep inflation low, often leading to a negative pressure on public sector deficits. Lower public spending further dampens the ability to invest in education. Thus, financial liberalization is intrinsically deflationary, leading to lower employment and wage growth (Epstein and Yeldan 2009). Van der Hoeven and Luebker (2007) argue furthermore that financialization has increased macroeconomic instability in many developing countries with a more than proportional negative effect on the income of poorer workers and a consequent worsening of both functional and primary income inequality.

4.4 Technical Change

Technological change influences the distribution of income through its effect on different factors of production. If technological change results in greater demand for skilled labour (more educated or more experienced) rather than for unskilled labour by increasing its relative productivity, the skill premium—the ratio of skilled to unskilled wages—might increase, driving at the same time an increase in income inequality (unless compensating measures are taken). Technological change also affects the functional distribution of income by raising the productivity of, and returns to, capital relative to labour. Primary income inequality might increase therefore as capital incomes are less equally distributed and accrue to the upper income deciles of households. A declining labour income share means that that aggregate demand is depressed because income shifts from those with a high propensity to consume to those with a lower propensity to consume (firms and the wealthy). This then leads to a lower employment rate and downward pressure on wages. The growth of wage rates lags behind growth of labour productivity (possibly because of the presence of a large pool of rural surplus labour typical of many developing countries). The pool of surplus labour weakens the bargaining power of labour and depresses wages in the non-agricultural sectors, contributing to declines in the labour income share when globalization and market-oriented reforms lead to rapid growth (ADB 2012).

However, it would be wrong to focus on the skill premium in isolation, as there may well be a race between technological progress, on the one hand, which tends to increase the demand for skilled labour, thereby raising more than proportionally the wages of the skilled labour, and educational attainment on the other, which increases the supply of skilled labour and thereby having a downward effect of the wages of skilled labour (Tinbergen 1975). Goldin and Katz (2008) argued that, following a long period of relatively stable technological progress, rapid progress in information technology and the widespread use of computers in the workplace accelerated the rate of technological change in the 1980s and 1990s. The resulting increase in the demand for skilled labour outpaced educational advances in developed and developing countries alike, causing increases in wage inequality (UNCTAD 2012). However, the theory of a race between technological progress and supply of education rests on two premises, which may not be always fulfilled. The first one is the assumption that the education system can indeed provide the new skills required by technological change. The second one is that the labour market will cause the excess supply of skilled workers to bring their wages down. However, in many countries highly paid interest groups can neutralize downward pressure on their wages arising from labour market dynamics.

Concerns about inequality in developing and transition economies often focus on distributional effects stemming from changing production structures. Such effects are likely to be larger in developing than in developed countries because productivity gaps between different economic sectors, as well as among enterprises within the same sector, tend to be much larger in developing countries (McMillan and Rodrik 2011).

5 Evidence of Globalization and Income Inequality

5.1 General

Evidence of globalization affecting income inequality is provided in Fig. 10.5, where the Gini index of household market incomeFootnote 10 is plotted against the Globalization indexFootnote 11 for a sample of all countries in the world.

Figure 10.5 shows that the rise in the Gini index coincided with an increase in globalization. An analysis based on a data set from 1992 to 2005 (UNDP 2013) found that this strong correlation for all countries holds also when high-income (developed) and developing countries are considered separately. The correlations between the two indicators in each group are 68 per cent and 67 per cent respectively.

5.2 Globalization and Factor Income Inequality

The decline in labour income shares, during a phase of globalization, is not limited to specific sector but is an economy-wide phenomenon. Rodriguez and Jayadev (2010) investigated by means of a large panel data set for 135 developed and developing countries whether the secular decline in labour income shares is due to the decline of the labour income share in particular sectors or whether the decline in labour income share is economy wide. By matching national economy-wide results with results for the labour income share at the three-digit industry level, they conclude that the decline in labour income shares is primarily driven by decreases in intra-sector labour shares as opposed to movements in activity towards sectors with lower labour income shares. This suggests that the decline in labour shares is driven by economy-wide phenomena and therefore, national policies rather than industry specific policies are needed to reverse it.

The downward trend of the labour income share is even more pronounced in many emerging and developing countries, with considerable declines in Asia and North Africa and more stable, but still declining, labour income shares in Latin America (ILO 2011). ILO 2013 and Stockhammer 2013 have used an enlarged panel data set encompassing developed, developing and emerging economies to investigate the drivers of declining labour income shares. The average of labour shares in a group of 16 developing and emerging economies, declined from around 62 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in the early 1990s to 58 per cent just before the crisis.

These results confirm of Diwan’s earlier observation (Diwan 1999) that currency crises are associated with sharp declines in the labour income share, reiterating that the cost of financial instability affects labour disproportionally. More recent analyses (Stockhammer 2013; ILO 2013) find decline of the welfare state and weakening of labour market institutions in addition to financialization, globalization and technical change as drivers of factor income inequality.

The decline of the labour income share in developing countries is more worrying as, according to past patterns of development, the labour income shares in developing countries should actually rise with increasing per capita GDP (Fig. 10.6).

The unadjusted labour income share and GDP per capita in 2008

Source: ILO 2014, Figure 8.2

More recent data confirm the trend of a declining labour income share observed before the crisis of 2008. In a recent study, using an augmented data set (distinguishing labour income share in the corporate sector and in the whole economy), Karabarbounis and Neiman (2015) found that the global corporate labour share has exhibited a relatively steady downward trend, from a level of roughly 64 per cent, reaching about 59 per cent at the end of the period, while labour’s share of the overall economy also declined globally from 58 per cent to 53 per cent.

Trapp (2015) used an original way to determine changes in the labour share in developing countries, by collecting social accounting matrices of a large number of countries to estimate labour income shares in these countries. Her finding confirms the other analyses mentioned earlier of a downward trend of the labour income share in most developing regions (Fig. 10.7). East Asia and the Pacific is the region that experienced the fastest decrease (on average 14 percentage points since 1990), closely followed by Eastern Europe and Central Asia (both about 11 percentage points), and Latin America and the Caribbean (both about 10 percentage points). A considerable decline also occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, where labour income shares fell by 6 percentage points between 1990 and 2011. Exceptions to the downward trend are only visible in South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, where labour income shares fluctuated, but more or less remained on a stable average level (note that labour income shares in these regions should actually have increased, as mentioned earlier, given the positive growth in GDP in these regions).

Labour income share by region, 1990–2011

Source: Trapp 2015, Figure 6

Looking at different GDP per capita groups (according to World Bank country classifications), one notices that the negative trend occurs in all income groups. However, it is more pronounced in low-income countries, followed by lower middle-income and upper middle-income countries (Fig. 10.8).

Labour income shares by GDP classification 1990–2011

Source: Trapp 2015, Figure 7

The last two sets of analyses range until 2011–2012, that is, they include and well extend beyond the financial crisis and its immediate aftermath. It is clear from these analyses, that the decline of the labour share has not halted or been reversed after the financial crisis. And also do not attest to the sometimes-heard thesis that the financial crisis did hit capital owners harder than ordinary workers and their families. We see actually that the share of the top 1 per cent is increasing in almost all developing countries, a consequence of the declining labour share and of greater inequality between wages themselves.

5.3 Globalization and Top Incomes

If the labour income of the top 1 per cent of income earners were excluded in the nationwide computation, the decline in the labour income share would probably have been even greater than what we observed in Fig. 10.8. This reflects the sharp increase, especially in English-speaking developed countries, of wage and salaries (including bonuses and exercised stock options) of top executives, who now cohabit with capital owners at the top of the income hierarchy (Atkinson et al. 2011). Data for the share of top incomes in developing countries are scarce, but for 15 developing countries, for which data are available, a similar trend as in developed countries can be observed (Fig. 10.9). For example, the share of the 1 per cent top income group in Colombia reaches 20 per cent, a level similar to that in the United States. It is increasing also for all other countries in the sample, except for Indonesia.

The incomes of the top 1 per cent (15 developing countries)

Source: The World Top Income Database. http://topincomes.g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu, Downloaded with permission

Box 10.1 Thomas Piketty: Capital in the Twenty-first Century

Piketty (2014) has engendered a heated discussion about the growing income inequality, and especially that of wealth, in industrialized countries and what to do about it. How important are Piketty’s analysis, findings and policy advice for developing countries?

The beginning of Piketty’s (2014) discussion gives an analysis of income distribution in the world and he rightly argues that economists must have a more historical and political perspective (p. 574). Very important is also his analysis of the Kuznets curve (p. 13–14). According to this curve, inequality increases in low-income countries, inequality somewhere has a peak at middle-income levels and then decreases at a high-income level. Piketty argues that the decline of inequality in high-income countries, that took place in the years after the Second World War, did not prove at all lawfulness of the Kuznets curve, but was due to special circumstances in developed countries at that time, which are now no longer valid. In developed countries, income inequality rises again. This observation is important for developing and emerging countries. Attention to inequality must always play an important role in poorer countries, as waiting for better times when economic growth takes place is often an illusion.

Piketty’s analysis rests on two important premises. The first is that the ratio of capital to national income increases. This is the result of two forces: the increase in the return of capital in national income (the so-called capital income quote) and the rapid growth of top income, not only through capital income but also by huge high salaries and bonuses in certain sectors (page 333ff). The second premise of Piketty is that, firstly, the income growth of capital, in contrast to the assumptions of the neoclassical economists, is greater than the growth of national income (the famous formula r > G) and, secondly, that people with more capital, by investing better, in the long run, have higher income from capital than people with little capital. (Thus, a higher r for the rich than for the poor.)

As for developing countries, we see also a growing share of capital income in national income. It is less clear, though, whether the relationship of return of capital growing faster than GDP has already taken place in developing countries. The growth rate of GDP, even if it is due to population growth, is, with great variations, higher than in developed countries. Piketty himself assumes a current growth rate in developed countries of 1–1.5 per cent and argues that today’s developing and emerging countries will also attain such a growth rate at the middle or end of the twenty-first century. But so far this is not yet the case. Even a decade or two is long for predictions in the rapidly changing world.

Piketty (2017) comments on the situation in developing countries as follows: “The basic structure of inequality is not the same in post-apartheid South Africa, ex-slave societies like Brazil, oil-rich kingdom’s and Islamic republics like in the Middle East, or post-caste societies like India”. Piketty is therefore wary of economic laws explaining inequality and emphasizes societal and political factors.

Piketty’s work implies that developing countries and emerging countries must take stronger measures to counteract current (growing) income inequality (especially the growing income gap between capital and labour income as well as high wage rewards in certain sectors) than only emphasizing higher taxes on capital.

6 Reducing Income Inequality in Developing Countries

6.1 General

Which measures are necessary to stem the growing inequality in developing countries?Footnote 12 To answer this question, it is useful to return to Table 10.2 which distinguishes between exogenous and endogenous drivers of inequality. Exogenous drivers of inequality are shaped by international trade and investment agreements as part of an improved system of global governance, giving developing countries more policy space and allowing them to set in motion a process of structural change. But equally important are the endogenous drivers of inequality. The literature has shown that domestic policies can have a great effect on inequality (Dagdeviren et al. 2004). National institutions and national policies can play an important role in reducing primary or market outcome inequality. Moreover, the degree of inequality reduction from primary to secondary distribution does not seem to be related to the level of initial primary or market outcome inequality.

The adverse effect ofexogenous drivers, such as financial and trade globalization, on income inequality during the past three decades have been exacerbated by national policies that had a negative impact on income distribution.Monetary policies that emphasized price stability over growth, labour market policies that weakened bargaining position of labour vis-à-vis employers and fiscal policies that prioritized fiscal consolidation at the expense of benefits and progressive taxation, all contributed to driving income inequality. It is important to point out these exogenous effects on national income distribution and to analyse and propose changes in the international and financial systems to redress this.

Despite the effects of exogenous drivers, national policies (including a strengthening of institutions to deal with inequality) can be reoriented to promote income equality. National policies can play an important role on reducing income inequality. Additionally, the right mix of macroeconomic, fiscal, labour market and social policies can reverse the rising trend in income inequality as exemplified by various Latin American countries. A number of countries in that region have been able to arrest the upward trend of growing inequality, despite being subject to the continuing challenges of globalization, like all countries in the world.Footnote 13

6.2 Macroeconomic Policies

Macroeconomic policies address the overall aggregates of the economy: prices, output, employment, investment and savings, government balances and balances on the external account. There are three major policies to manage these macroeconomic aggregates: exchange rate policies, fiscal policies and monetary policies (Ghosh 2007). The emphasis on full employment and growth in the post-Second World War years led in most countries to an increase in the wage share and an improving functional income distribution (Ocampo 2003). However, since the 1980s onwards, fiscal balance and price stability moved to centre stage, replacing the Keynesian emphasis on real economic activity. The shift in macroeconomic thinking in a large number of developing countries was mainly driven by the earlier mentioned Washington Consensus. The changes in monetary, fiscal and exchange rate policies under the aegis of the Washington Consensus were often (new) drivers for growing inequality (e.g. Cornia 2004; Taylor 2004; van der Hoeven and Saget 2004).

Monetary policy used the interest rate as a policy instrument to curb inflation below the 5 per cent guideline set by international financial institutions in developing countries (UNESCAP 2013). This policy effectively induced a recession in developing economies by increasing the cost of capital, thus lowering both investment and growth. And indeed, growth was lower in the 1980–2000 period compared to 1960–1980 (Cornia 2012). Furthermore, these contractionary monetary policies led to a surge in unemployment and in several cases even an increase in informal employment. Financial liberalization and high real interest rates encouraged large capital inflows including speculative capital. This led to an appreciation of the Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) that in turn led to a worsening of the trade balance as exports became more expensive abroad and imports cheaper. While increased capital flows increased demand, the appreciated REER meant that this demand is satisfied with imports rather than local production, thus depressing growth and employment.

Exchange rate policies adopted during the period to achieve macroeconomic stability had adverse impacts on inequality. In this context, many developing countries were encouraged by international financial institutions to maintain either a fixed nominal exchange rate regime or a free-floating exchange regime. Each of these “two corner solutions” put developing economies at the risk of currency crises and large currency devaluations. On the one hand, fixed nominal exchange rate regimes are unable to cope with external shocks such as trade shocks, and are prone to speculative attacks, thus increasing the risk of a currency crisis. On the other hand, free floats often turn into a ‘free fall’, given the volatile and pro-cyclical behaviour of capital flows (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009). Massive currency devaluations and crises that arose as a result of adopting these two ‘extreme’ exchange rate regimes led to rapid declining real wages, often affecting lower wage earners disproportionately in comparison to other wage earners, capital owners and land owners (van der Hoeven and Luebker 2007).

Capital account openness and the resulting large capital inflows combined with high interest rates meant that banks were more likely to lend to high-risk/high-return activities in sectors with lower concentrations of unskilled workers such as finance, insurance and real estate. Conversely, poor households and the small and medium enterprises (SME) sector, where most of the poor and unskilled workers are employed, were locked out of the benefits of the expansion in credit markets due to lack of collateral, insufficient profit margin and prohibitive transaction costs (Cornia 2012). As noted by UNESCAP (2013, p. 153), this asymmetric distribution of the benefits of finance can “lead to poverty traps, negative effects on social and human development and a rise in inequality”.

As a result of the Washington Consensus, fiscal policies abandoned their development and distributional role and became geared towards achieving stabilization. Policies to maintain low budget deficits (or even surpluses) were seen as essential to achieve low inflation. This was achieved through expenditure cuts, with little regard for the composition of those cuts and whether they happened at the expense of public investment in infrastructure or social expenditures (UNESCAP 2013). This had an adverse impact on both growth and distribution. Public investment in infrastructure diminished with a negative effect on both growth and poverty reduction, while expenditure cuts in social services like health and education worsened tertiary income distribution and reduced the opportunities for social mobility.

In addition to expenditure cuts, governments reduced trade taxes to encourage globalization and income and corporate tax rates to encourage the private sector. The resulting fall in tax revenue in turn led to higher government deficits, which necessitated even further expenditure cuts. Indirect taxes that were introduced to compensate for the loss of tax revenue, such as value-added tax (VAT), did not generate enough revenue but reduced the progressivity of the taxation system. In summary, the redistributive role of taxation was minimized by reducing the size of tax revenues available for social spending and by making the tax system less progressive. Issues of fiscal policy are discussed in more detail in the following section on the drivers of secondary and tertiary inequality.

6.3 Labour Market Policies

Changes in labour market policies have been an important driver of inequality (van der Hoeven and Taylor 2000). In particular, the labour market policies undertaken in the wake of structural adjustment policies as part of the Washington Consensus have increased income inequality in all countries where these policies have been applied (Cornia 2004; van der Hoeven and Saget 2004). Especially relevant for income inequality are the labour market policies concerned with the distribution of wages, the gender gap therein and minimum wages.

Not only has the share of wages in national income declined as discussed in the section on exogenous drivers and functional inequality but also the distribution of wages themselves has become more unequal. The distance between the top 10 per cent and the bottom 10 per cent of wage earners has increased since 1995–1997 in 23 out of 31 countries surveyed; while the proportion of workers with low pay (defined as less than two-thirds of the median wage) has also increased in 25 out of 37 countries (ILO 2008a, b). These trends towards growing inequality remain strong even when other income sources, taxation and income transfer are considered (ILO 2011). Gropello and Sakellariou (2010), in reviewing levels and trends in education and skill premiums, and skilled labour force, across eight East Asian countries, observe that while there are increasing proportions of skilled/educated workers over the long run across the region, this is combined with stable or increasing education/skill wage premiums. The importance of skills premia as driver of inequality becomes even stronger in countries where access to post-secondary education is more skewly distributed than incomes (Sharma et al. 2011).

Conventional economic theory would predict that education and schooling would reduce skill premiums in the medium term as the supply of skilled labour increases in response to the higher wage premia. However, this did not seem to happen in many developing countries. Behar (2011) reviews why schooling has not countered the pervasive rises in wage inequality, driven by skill-biased technical change (SBTC). He concludes that technological change is skill-biased in the South simply because it is in the North, which causes permanently rising wage inequality in the South. Other authors however caution against seeing SBTC as a major driver of wage inequality. For example, Singh and Dhumale (2004) show evidence for middle- and high-income countries that supports the SBTC hypothesis only weakly. They suggest other factors such as changes in remuneration norms, labour institutions and financial markets being more relevant in explaining rises in wage inequality than SBTC.

Another important driver of wage inequality is the gender gap. Elson (2007) and Heintz (2006) find that many factors drive the gender gap in earnings—differences in education, shorter tenure in the labour market and interruptions in women’s employment histories associated with raising children. Nevertheless, a large quantity of research has shown that, even after controlling for education, age and job tenure, gender gaps in remuneration remain. In part, this is due to the persistence of earnings gaps within occupational categories (Horton 1999), suggesting that wage discrimination remains influential. Research also suggests that earnings differentials between men and women are also apparent across the various forms of informal work (Chen et al. 2005). Furthermore, Seguino (2000) finds that firm mobility is one contributing factor to higher wage inequality in Taiwan. Since women are more concentrated in industries in which firm mobility is high, their bargaining power, and hence their wages, would fall relative to men as global integration progresses.

Several ILO studies (Saget 20012008; ILO 2008a, b) have indeed observed that, as a consequence of structural adjustment, liberalization policies and changes in labour market institutions, the minimum wage in a sizeable number of countries is so low that it does not contribute to reducing inequalities or poverty reduction and has become meaningless. This has also led to poorly developed collective bargaining where frustrated minimum wage consultations are the only forum where trade unions can make their demands known.

On the other hand, changes in labour market policies, that improve and enforce minimum wage policies, can have a positive impact on reducing inequality (Freeman 2005). For instance in the early 2000s several Latin American countries revised their stance on minimum wages, with important increases, in some countries even a doubling of previous levels. These changes have been an important driver of reductions in income inequality in Latin America (Lopez-Calva and Lustig 2010) and gender inequality in employment (Braunstein and Seguino 2012).

6.4 Wealth Inequality and Intergenerational Transmission as Drivers of Inequality

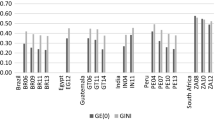

One of the important drivers of income inequality is the large inequality in wealth and in human capital. Wealth is distributed far more unequally than incomes in all countries for which data are available (Fig. 10.10).

Davies (2008) shows that the Gini index of the distribution of personal wealth ranges from 55 to 80, which are in all countries higher or much higher than for the distribution of primary (market) income. Another feature of the distribution of wealth is that the rich (high-income countries) hold greater proportions of wealth in financial assets than poorer or middle-income households (countries) where wealth is predominantly held in real assets such as land, houses and farm infrastructure.

Closely linked to the question of wealth is the intergenerational transmission of inequality. According to the Credit Suisse (2012), inheritance is an important component of wealth. Worldwide, 31 per cent of Forbes billionaires inherited at least some of their wealth. If China, Russia and other transition countries are excluded, the figure is 38 per cent. More broadly, Credit Suisse (2012) suggests that inherited wealth likely accounts for 30–50 per cent of total household wealth in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. In low-growth or traditional societies, the share is probably higher. At the other end of the scale, very little household wealth in today’s transition economies was inherited.

Equally dominant is the effect of acquirement of human capital. The previous section alluded already to the higher education as a driver for greater inequality in some Asian countries and to the fact that access to higher education is still skewed and often depending on family’s wealth and incomes. Stephen Machin (2009) shows for example how important the influence of family background is on students’ test scores. In 53 out of 54 countries, including developing and emerging countries, the family background is statistically significant and the implied gaps in test scores are large. According to ECLAC (2010), the pattern of secondary school graduation in the Latin American region has increased substantially but contrary to what was expected has remained highly stratified in secondary and tertiary completion rates. While gender parity has been more than achieved (a greater percentage of young women than men complete secondary school), in general the average graduation rate is very low (51 per cent), and its distribution very large: in the first quintile, only one in five young people will complete secondary school, while four in five will do so in the fifth quintile. These contrasts show that education in its current form reinforces the intergenerational transmission of inequality instead of reversing it.

6.5 Fiscal Policy: Taxes and Transfers

Fiscal policy is an important driver of higher (or lower) income inequality because it affects both the secondary and tertiary income distribution.

Fiscal policies are mainly determined by a combination of political will and institutions of economic and social governance and can vary a great deal between countries, even between countries with similar levels of development. Figure 10.11 shows the maximum, minimum and median reduction in inequality from primary to secondary distribution by income groups in the early 2000s decade.

For all country groupings there is a great variation in the reduction of primary income inequality, especially noticeable for the low-income category countries, where the highest level of reduction in inequality changed from under 10 per cent before 2000 to over 40 per cent after 2000 (UNDP 2013). National institutions and national policies can therefore play an important role in reducing primary inequality, in developing countries also.

Moreover, the degree of inequality reduction from primary to secondary distributions does not seem to be related to the level of primary inequality. Luebker (2013) investigated for a select group of developing and developed countries how policy drivers of taxation and subsidies affect primary and secondary distribution and found a simple correlation between Gini indices for the primary and secondary distribution of only r = 0.499 (p-value: 0.011). Initial inequality thus matters, but can explain only about half of the variation in the Gini indices from primary to secondary inequality.

Transfers, more than taxation, can be very progressive and have a strong impact on reducing inequality. ADB (2012) argues that tax systems tend to show a mildly progressive incidence impact, but that direct cash transfers and in-kind transfers can be quite progressive unless there are serious targeting problems. The international experience shows that the expenditure side of the budget (including transfers) can have a more significant impact on income distribution. Cash transfers to lower income groups through government social protection programmes have had a major impact on inequality in a number of developing countries. In Latin America and other developing regions, the system of cash transfers (either conditional or unconditional) to alleviate poverty has gained importance over the past decades. Lustig et al. (2012) find that these cash transfers are also important drivers for reducing income inequality. For countries where information is available, they found that these various systems of transfers drove inequality down, ranging from 7 percentage points in Argentina to 1 percentage point in Peru.

6.6 Fiscal Policy: The Role of Public Expenditure

How does government expenditure on social sectors drive reduce the tertiary income inequality? Or in other words, how much does income inequality change when the imputed value of government expenditure is added to net household incomes (secondary income)? An important point is of course which types of government expenditure are considered in this respect. It is not a foregone conclusion that government expenditure has an equalizing effect in reducing secondary income inequality. It is foreseeable that higher income groups might benefit more from government expenditure than poorer groups (e.g. heavily subsidized hospitals in well-off urban areas, tertiary education, opera tickets, etc.).

While the prime objective of social services is often not redistribution, but the provision of a decent education, basic health care and acceptable living standards for all, they are in fact redistributive. Expenditure programmes in the social sectors (education and health) are more progressive the more is spent in relative and absolute terms on those goods and services more frequently used by the poor (basic education and primary health care). However, the effective targeting of lower income groups in expenditure programmes is hard to design and implement.

Lustig et al. (2012) has performed in-depth studies on several countries to understand how government taxes, subsidies and expenditure have affected different forms of inequality.Footnote 14 Figure 10.12 shows that the reduction from secondary inequality (disposable income) to tertiary inequality (final income) can be substantial. In Argentina and Brazil, the Gini index dropped substantially from 46.5 to 38.8, and from 54.2 to 45.9, respectively, and in Bolivia and Mexico, from 46.5 to 42.5 and from 53.2 to 48.2, respectively.

7 Conclusion

Over the past 30 years, on average, household income inequality has risen in both high-income (developed) and developing countries. Countries moving up income classification have had steeper increases in income inequality than most other countries. Examining regional trends over the whole period from the early 1990s, the average inequality fell in some regions (Latin America) and rose in others (Asia).

Looking at periods before and after the turn of the century shows a non-linear pattern in some countries, inequality rose during the 1980s and 1990s but then fell in the 2000s; in others, inequality fell during the 1980s and 1990s but rose in the 2000s. However, despite reversals in some countries, the intensity of change has been greater in the direction of rising income inequality. It remains therefore important to focus on drivers of income inequality and by examining different forms of income distribution, such as functional distribution, wage distribution, primary distribution (household market income), secondary distribution (market income corrected for taxes and subsidies) and tertiary distribution (taking into account imputed household income from services).

Globalization and especially financialization and to a certain extent skills-based technical change have been important exogenous drivers of inequality. These drivers have in various cases strengthened existing patterns of inequality through a stubbornly high wealth inequality and through intergenerational transfers of inequality due to skewed access to higher-level education.

The adverse effect of financial and trade globalization on income inequality during the past three decades has been exacerbated by national policies that had a negative impact on income distribution. Monetary policies that emphasized price stability over growth, labour market policies that weakened bargaining position of labour vis-à-vis employers and fiscal policies that prioritized fiscal consolidation at the expense of benefits and progressive taxation, all contributed to increasing income inequality.

However national policies, including a strengthening of institutions to deal with inequality, can play an important role on reducing income inequality. Several countries have managed to use fiscal policies to mitigate a high primary income inequality down to lower levels of secondary and tertiary inequality. Additionally, the right mix of macroeconomic, fiscal, labour market and social policies can reverse the rising trend in income inequality as exemplified by various Latin American countries.

Box 10.2 Inequality and Sustainable Development Goals

Various authors (van der Hoeven 2012; Vandemoortele 2011; Melaned 2012) have argued that the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), established in 2000 for a period of 15 years, by emphasizing targets at a global level (with implications for targets at the national level), have ignored the inequalities that averages conceal. They suggested therefore that attention to inequality should be a basic element of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), established in 2015 for a period of 15 years, and that targets for all SDGs should be broken down for different socio-economic classes or for different income groups. These argumentations have been strengthened by recent analyses that conclude that greater equality and more equal access to government services will contribute to improved and sustained development in general (Wilkinson and Pickett 2009).