Abstract

While innovation remains a focus of policymakers, very little is known about how older entrepreneurs adopt new technology or introduce new products. Similarly, demographic studies of entrepreneurship are mostly interested in non-age-related demographic influences on entrepreneurial behavior. In this study we examine how age influences the choice of innovative entrepreneurship by considering both technology adoption and product innovation by those who enter entrepreneurship late in their career (over 50 years old). Our results suggest that as in other spheres of life, third-age entrepreneurs tend to lag behind their younger counterparts in technology adoption and innovation. This is extremely significant as, due to the aging population in many countries, it could have serious consequences for the overall development and growth of high impact entrepreneurship. We suggest some measures to address this issue.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

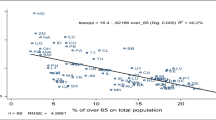

In recent years, researchers have become increasingly interested in older entrepreneurs (Clegg and Fifer 2014; Halvorsen and Morrow-Howell 2016; Schøtt et al. 2017). With aging populations, policymakers in many western economies are increasingly trying to encourage entrepreneurship among their older populations (Wainwright and Kibler 2014; Schøtt et al. 2017). Data collected from large-scale surveys also point toward increasing entrepreneurship by older people. Kelley et al. (2013) found that although in absolute terms entrepreneurship among older people is lower than in younger age groups, if we consider the labor force participation rate,Footnote 1 the entrepreneurial activity of older entrepreneurs is much greater. According to the Kauffman index of entrepreneurial activity, while in 1996 14.3% of the 55–64 age group were new entrepreneurs, this figure increased to 23.4% in 2012 (Fairlie 2013). Using data from 35 European countries, Kautonen (2013) found that although the entrepreneurial potentialFootnote 2 of older people is lower than in other age groups, it is by no means marginal. A significant number of older people are intending to start a business, involved in early-stage entrepreneurial activity, or considering entrepreneurship as a late-career alternative (Kautonen 2013). Similar evidence from the GEM survey across 70 countries suggests that older-age entrepreneurship is no longer an oxymoron (Wainwright et al. 2011; Hudson and Goodwin 2014; Schøtt et al. 2017). Some authors even consider it the new dawn or the new normal (Isele and Rogoff 2014) noting that “fifty is the new thirty” (Kautonen and Minniti 2014).

Also known as third-age entrepreneurship,Footnote 3 entrepreneurship by older people has emerged as a promising field of study within entrepreneurship. Studies show that both pull and push factors encourage third-age entrepreneurs (Gimmon et al. 2016; Stirzaker and Galloway 2017). On one hand, young retirees are increasingly attracted toward entrepreneurship to maintain their lifestyle and flexibility (Colovic and Lamotte 2012; Lamotte and Colovic 2013). On the other hand, an increasing number of older people are forced to start their own business as a source of income because they are excluded from the labor market (Kautonen et al. 2011; Stirzaker and Galloway 2017). Recently, Kautonen et al. (2017) identified several research gaps in the study of third-age entrepreneurship. For instance, what type of entrepreneurship do third-age people prefer? In this regard, the study by Bonte et al. (2009) shows that older people are less likely to pursue opportunities in the high-tech sector. While limited in their coverage, these findings raise concerns about the effect of demographic aging on a society’s capacity to produce high impact entrepreneurship, especially involving innovation (Frosch 2011; Lamotte and Colovic 2013). Moreover, as entrepreneurship is the vehicle through which knowledge that leads to innovation is introduced into the economy, it is necessary to understand the propensity to innovate among new entrepreneurs (Acs et al. 2009). As the article by Bonte et al. (2009) mainly focuses on high-tech and a single country, the main objective of our study is to compare the type of entrepreneurship preferred by third-age people and those in other age groups across countries.

To that aim, we have reviewed the literature in different disciplines and conducted an empirical study on a large data sample. Our research contributes to knowledge on third-age entrepreneurship in two ways. First, we highlight a phenomenon that has rarely been studied. For instance, while innovation remains a focus of policymakers, very little is known about how older entrepreneurs adopt new technology or introduce new products (Schneider and Veugelers 2010; Czarnitzki and Delanote 2012; Maula et al. 2007). Similarly, demographic studies of entrepreneurship mostly investigate non-age-related factors (Low and MacMillan 1988; Arenius and Minniti 2005). To our knowledge, except for Colovic and Lamotte (2012), on which this chapter builds, no other research has specifically investigated this issue, although, due to demographic change in Western societies, the elderly increasingly attract the attention of researchers. Second, our empirical study is based on a large database, thus improving the generalizability of the results.

The rest of this chapter is structured as follows. Sections 2 and 3 review the literature on the influence of age on entrepreneurship and innovation. Section 4 describes the database and the methodology we used. Section 5 tests our hypotheses. Section 6 discusses the main findings, highlights the limitations of the research and future research directions, and offers recommendations for supporting of third-age entrepreneurs.

2 Age and Entrepreneurship

The individual level factors that influence entrepreneurial behavior can be categorized as psychological, motivational, cognitive, and demographic. These factors influence entrepreneurship directly, either individually or in combination. However, unlike psychological, motivational, and cognitive factors, which can be context dependent (Welter 2011; Zahra et al. 2014), demographic factors such as gender and age are “inherent factors” of entrepreneurship (Parker 2004). Demographic studies of entrepreneurship mainly focus on gender. Interestingly, age seems to be present in most studies but mainly as a control factor rather than a substantive variable. In other words, although the effect of age is taken into account, it is simply explained away while other factors dominate explanations of entrepreneurial behavior. However, since age affects several of these individual level factors, it becomes an important factor in the decision to become an entrepreneur (Parker 2004; Lévesque and Minniti 2006; Minola et al. 2014). Indeed, recent studies show that age distribution is a key factor in determining the rate of entrepreneurship in a region (Bonte et al. 2009; Lamotte and Colovic 2013). In this regard, previous studies linking age and entrepreneurship suggest an inverted U relationship between age and the decision to start a business (Bonte et al. 2009), with the proportion of people trying to start a business being highest in the 25- to 35-year age group (Lévesque and Minniti 2006; Reynolds 2007). Mueller (2006) finds a positive, curvilinear relationship between age and the desire to start a business, peaking at the age of 41. Most empirical analysis that considers age as a control variable suggests that the probability of creating ones’ own business is highest among the relatively young (Blanchflower 2004; Lévesque and Minniti 2006).

The issue of the influence of age on entrepreneurial behavior can be examined from an employment choice perspective. As an employment choice decision, a long tradition of research highlights the significance of risk attitude in the choice of entrepreneurship over salaried employment. However, most studies do not consider the interplay between risk and age in influencing employment choices over people’s entire life. However, it is generally known that risk aptitude decreases as people grow older (Josef et al. 2016). If the same applies to employment choice, it can be surmised that as individuals grow older, they are less likely to choose entrepreneurship over salaried employment. Lévesque and Minniti (2006) proposed that the dynamic interplay between age, risk, and employment choice can be explained if “time” is taken into account. Based on Becker’s time allocation model, the authors propose that as time is an important and finite resource, people prefer an income-producing activity that produces the highest expected utility within a given time span, in this case the person’s life span (Lévesque and Minniti 2006). Moreover, as entrepreneurship does not produce an instant (or riskless) return, the older the person, the less time they have to enjoy the future returns from business activity. This reduces the attractiveness of entrepreneurship over salaried employment, as people grow older. By incorporating time, Lévesque and Minniti’s (2006) theoretical model suggests that in addition to attitude toward risk, activities that involve a “time commitment component” before producing an income, such as a new business, are less attractive than activities with immediate payoffs such as salaried employment.

However, it should also be noted that entrepreneurial ability is likely to increase with age, as people develop or acquire human, social, and financial capital over time (Curran and Blackburn 2001; Fairlie and Krashinsky 2012). The optimal time to be an entrepreneur should therefore be when one has developed sufficient human, social, and financial capital, but risk aversion and the emphasis on time are not yet too important. Hence, the preference of younger people for entrepreneurship. Although older people are more likely to be able to create a business than their younger peers, they are less likely to be willing to do so (Curran and Blackburn 2001).

However, the above explanation does not indicate the relationship between age and innovative entrepreneurship. When choosing innovative entrepreneurship, people face not only the risk arising from the employment choice decision but also that arising from the nature of innovation (Koellinger 2008; Dencker and Gruber 2015; Bayon et al. 2016). Moreover, the choice of innovative entrepreneurship requires both the ability and the desire to develop and implement innovative ideas, a propensity that might differ across different age groups.

3 Age and Innovation

Innovation propensity is essential for innovative entrepreneurs. Lumpkin and Dess (1996) define the propensity to innovate as a tendency to initiate and support new ideas, novelty, experimentation, and creative processes that may result in the creation of new products, new services, or new processes technology. Such a propensity may be affected by the biological process of aging (Meyer 2011; Rietzschel et al. 2016). Studies on the evolution of cognitive abilities during a lifetime, of which Desjardins and Warnke (2012) provide a comprehensive review, are particularly interesting. They show that cognitive decline can start as early as the age of 20 and that it accelerates from the age of 50 (Hertzog et al. 2008). However, to understand the effect of cognition on the creative process, it is necessary to consider two types of intelligence that undergo cognitive changes: fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence. While the former refers to the ability to reason logically and solve problems, the latter is the ability to use skills, knowledge, and experience (Cattell 1971). Fluid intelligence is genetically and biologically determined and tends to decline from adulthood. However, crystallized intelligence, which is socially and culturally determined, tends to increase until the age of 55, stabilizes up to the age of 75, and then declines (Baltes 1993; Desjardins and Warnke 2012). Baltes (1993) has suggested that the decline of fluid intelligence is offset by increased crystallized intelligence at least until the age of 75. In addition, studies have shown that creative ability decreases with age (Ruth and Birren 1985) because people are over influenced by their experience, which reduces their creative abilities. Thus, some abilities increase with age while others decline. In addition, physical and cognitive abilities depend not only on biological but also on behavioral, environmental, and social factors (Desjardins and Warnke 2012).

While changes in cognitive makeup may explain why older people may be less innovative, there are significant differences in the way younger and older people adopt new technology. For instance, the emerging literature on technology adoption by older people suggests that seniors are slower than other categories of workers to adopt innovative tools such as information and communication technology (Friedberg 2003; Weinberg 2004; Koning and Gelderblom 2006; Borghans and ter Weel 2002; Bertschek and Meyer 2008). Behaghel and Greenan (2010) provide one explanation for this phenomenon. Based on data from French firms, they suggest that workers over 50 are more reluctant to adopt technology because they receive less training during the implementation of technical changes. In the field of marketing too, several studies have shown that attitudes toward technology adoption vary with age. For instance, older people are often among the last to adopt innovative products, services, or ideas (Lunsford and Burnett 1992). Older consumers also seem to have a more negative attitude toward technology and use fewer new technologies (Gilly and Zeithmal 1985). This leads us to hypothesize:

- H1::

-

Third-age entrepreneurs are less likely to adopt innovative technology than those in other age groups.

While research findings generally conclude that older people are less likely to favor technology adoption, one of the very few studies that has looked at individual level factors influencing the choice of innovative entrepreneurship, by Koellinger (2008), suggests that age has no influence. However, the study by Bonte et al. (2009) on the innovation propensity of different age groups suggests the opposite. Based on regional data about German startups, the authors found a significant U-shaped relationship, between age and innovative entrepreneurship. Age groups 20–29 and 40–49 are the most active in terms of innovative entrepreneurship, while age group 30–39 is less active. This is an interesting result, because it suggests that innovative entrepreneurs are concentrated in specific age groups. The authors suggest several explanations for this. Accumulated experience and knowledge that help create an innovative enterprise increase with age. However, the mindset and routines that become established over time leave less room for the recognition of entrepreneurial opportunities or creativity, and this inhibits the decision to create an innovative company (Bonte et al. 2009). Moreover, attitudes toward risk could influence the choice of innovative entrepreneurship, especially that related to new product introduction, since older people are themselves reluctant to use innovative products. This leads us to suggest that third-age entrepreneurs are less likely to pursue product/service innovation than other age groups.

- H2::

-

Third-age entrepreneurs are less likely to pursue product/service innovation than those in other age groups.

4 Empirical Analysis

The objective of this chapter is to determine whether third-age people, defined as those 50 years old and above, choose innovative entrepreneurship more or less than other age groups (Curran and Blackburn 2001; Kautonen et al. 2011; Maâlaoui et al. 2013). We used the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) database. GEM is an annual assessment of entrepreneurial activity. The data come from surveys of a random sample of the adult population (APS) conducted between 2003 and 2013 on at least 2000 people per country. The database covers 100 developed and developing countries. From the main sample, we use the subsample of early-stage entrepreneurs (TEA) defined as those who have been engaged in an entrepreneurial activity for between 3 and 42 months at the time of the survey. The respondents are aged between 15 and 97. The full sample comprises 154,502 observations. We present the variables used in this study and data sources in Table 1.

The explained variables are binary variables Product innovation and Technology adoption. Product innovation, denoted by 1, is indicated when the product or service offered to the customers is considered new by all or some customers. Otherwise, it takes the value of 0. Technology adoption takes the value 1 when the technology or procedure required for production has been available for less than a year, 0 otherwise. In this sense, our definition of technology innovation is a broad one and includes procedures involved in the production/manufacture of the product or service. In other words, our explained variables take account of both product and process innovation. We consider the result of innovation rather than the intention to innovate, i.e., those in our sample are (or are not) in the actual process of introducing innovations. Our explanatory variable, third-age entrepreneur is binary. It takes the value 1 when the entrepreneur is 50 years old or more and 0 otherwise. We also include a set of control variables. Empirical studies have indeed highlighted the role of other personal characteristics of the entrepreneur, such as gender (Minniti and Nardone 2007) or education level (Davidsson and Honig 2003; Bayon et al. 2016), motivations (McMullen et al. 2008), and sector of activity (Thornhill 2006) in influencing innovative entrepreneurship. We also include country and year dummies in all regressions to control for country-level differences in terms of economic development and institutions over time.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the sample related to explanatory variables and age groups. It shows, for each age group, the distribution of entrepreneurs according to innovative products and technologies. For example, of 27,498 third-age entrepreneurs, 11,897, that is, 43.3%, offer an innovative product. In comparison, 44.8% of entrepreneurs who are less than 50 years old offer an innovative product. There is also a difference with respect to the use of new technologies. 12.9% of younger entrepreneurs rely on technology that has been available for less than a year, as against 10.7% for their older peers.

Table 3 presents the main descriptive statistics of the variables and a correlation matrix. The variance inflation factors (VIF) in all regression models are between 1.06 and 2.88, which confirm the absence of colinearity between the explanatory and control variables.

5 Results

Table 4 presents four models of probit regressions. In Models 1 and 2, the explained variable is Product innovation, while in Models 3 and 4 the explained variable is Technology adoption. Models 1 and 3 include only the control variables; Models 2 and 4 include the explanatory variable. We used the results in Table 4 to test hypotheses 1 and 2. All coefficients are significant at the 1% level with the exception of gender and motivation in Models 3 and 4. McKelvey and Zavoina’s R2 are relatively small but are consistent with comparable empirical studies. In addition, as Hoetker (2007) suggested, R2 for probit estimates cannot be interpreted intuitively or compared to those of OLS estimates. To facilitate interpretation of the results, we calculate the marginal values of probit estimates in Table 4. Marginal values indicate the observed result for the dependent variable when the explanatory variable changes from 0 to 1. Thus, starting from Model 2, we see that senior entrepreneurs are 1.8% less likely to offer a new product. Similarly, we observe that senior entrepreneurs are 1.6% less likely to use a new technology. These findings confirm our hypotheses.

The estimated coefficients for the control variables are also interesting. The estimated coefficient for gender is negative for process and product innovation. This suggests that female entrepreneurs are more innovative in terms of both product and technology. As expected, the higher education coefficient is positive for product innovation, suggesting that educated entrepreneurs are more likely to be innovative in terms of products. The estimated coefficients for the variable opportunity are particularly interesting. They are positive and significant for product innovation, but not significant for technology innovation. This clearly indicates that innovative entrepreneurs exploit product opportunities rather than technology opportunities. The estimated coefficients for technology sector indicate that innovative entrepreneurship is more common in areas of medium and high technology. This result is intuitive but important. In fact, innovation can occur in all sectors, including agriculture and retail.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

The aim of this study was to compare the innovativeness of older and younger entrepreneurs. Our empirical analysis shows that older entrepreneurs are less innovative than their younger peers with regard to both product and process innovation. These results support our hypotheses. Several explanations may clarify these results. From the gerontological perspective, third-age individuals suffer from a loss of cognitive functions, which reduces their ability to offer innovative products or to adopt innovative technologies. In addition, older business people are more reluctant to adopt new technologies and to obtain training in this area. They are therefore at a disadvantage when creating a new business, as they are less innovative. This reduced ability to innovate may affect the success of older entrepreneurs, as several studies have shown that the survival of young firms is largely dependent on their ability to innovate (Cefis and Marsili 2006; Buddelmeyer et al. 2010). Harada (2003) has also shown the existence of a negative relationship between the probability of success of an entrepreneur and his/her age, although the author does not suggest any particular reason for this. A lack of innovative ability could be an explanation.

The results of this research should however be nuanced for several reasons. First, the deterioration of cognitive abilities and reluctance to adopt new technologies do not affect all people the same way. As emphasized by Desjardins and Warnke (2012), the evolution of people’s cognitive abilities depends on interactions between multiple factors: biological characteristics, education, family and social environment, occupation, cognitive stimulation, and physical exercise. For example, those who exercise an intellectual profession that requires them to adapt frequently to technological change suffer less from the cognitive losses associated with aging (Valenzuela and Sachdev 2006). In contrast, recent studies show that retirement accelerates cognitive decline (Bonsang et al. 2012). Second, the propensity to innovate also depends on economic, social, and cultural development, which can be more or less favorable to innovative entrepreneurship. Thus, Koellinger (2008) shows that entrepreneurs are more likely to innovate in developed, high-income countries. Lee et al. (2004) show that a socially and culturally diverse environment facilitates the influx of specific human capital and the dissemination of information for innovation and entrepreneurship. Finally, the results of this research are valid over the study period but cannot be generalized to other periods. They may be affected by cohort effects, that is to say, by the specific characteristics of a generation or a structural change caused by specific major events, such as the development of IT or the Internet (Desjardins and Warnke 2012). Thus, being 50 years old today is not comparable to being 50 years old 10 years ago, especially in terms of entrepreneurship and innovation. Therefore, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution and positioned in the current context.

This study has several limitations, mainly due to the limitations of the database, which in turn open up possibilities for future research. First, the empirical analysis is based on survey data, a possible source of bias. In particular, the variables innovative products and technologies are based on the statements of entrepreneurs, although, as Koellinger (2008) suggested, innovation is a subjective concept that depends on the viewpoint of the observer. This limitation is particularly significant in the context of studies on generational differences, where the perception of innovation may be affected by the respondent’s age. Second, this study is based on the actual age of the entrepreneurs rather than their perceived age. However, perceived age may differ from actual age, especially for seniors, depending on their state of health, life expectancy, or the place of older people in society. A recent study by Kautonen et al. (2011) has shown that seniors’ entrepreneurial intentions depend among other things on their perception of entrepreneurship at different ages. Future research could examine the impact of perceived age on the propensity to create firms, particularly innovative firms. This development would be extremely relevant, as it would take into account the role of the economic and social environment in age perceptions. Third, this study does not specifically identify the reasons for the reluctance of third-age people to innovate. To complement this research, it would be interesting to analyze the barriers faced by seniors wishing to start an innovative company. In fact, studies on this topic are rare and do not focus on innovative entrepreneurship. Kibler et al. (2015) and Wainwright et al. (2011) show that society’s negative perception of older entrepreneurs, real or perceived, is a significant barrier to the development of third-age entrepreneurship. Other barriers that deserve investigation include funding difficulties generated by older entrepreneurs’ shorter time horizons. Fourth, this research includes product and process innovation but not organizational innovation, yet this could be important, particularly among older entrepreneurs because of their experience.

The study has practical implications for third-age entrepreneurs and public authorities. The most important recommendation is that people’s skills should be maintained or improved throughout life. Steps in this direction would limit the cognitive decline related to aging but also facilitate the adoption of new tools by seniors. Periods of inactivity, especially in later life, should not cause a loss of skills. Training or activities to maintain intellectual and physical activity should be promoted. Strengthening intergenerational knowledge transfers might also effectively combine fluid and crystallized intelligence. Finally, it is necessary to establish specific policies to promote and support third-age entrepreneurship, taking into account the particular challenges they may encounter in their entrepreneurial projects, such as negative perceptions of the company or access to financial resources. All these measures can be implemented by support organizations but also internally by companies wishing to help their employees to start a business.

Notes

- 1.

Older people are more likely to be retired and hence less likely to be actively looking for work. Hence, their labor force participation rate will be low.

- 2.

Entrepreneurial potential is defined as the number of people thinking about starting a business or in early-stage entrepreneurship (Kautonen 2013).

- 3.

Other terms associated with older-age entrepreneurship are gray entrepreneurship, senior entrepreneurship, or late-career entrepreneurship.

References

Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 15–30.

Arenius, P., & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 233–247.

Baltes, P. B. (1993). The ageing mind: Potential and limits. Gerontologist, 33(5), 580–594.

Bayon, M. C., Lafuente, E., & Vaillant, Y. (2016). Human capital and the decision to exploit innovative opportunity. Management Decision, 54(7), 1615–1632.

Behaghel, L., & Greenan, N. (2010). Training and age-biased technical change. Annales d’Economie et de Statistique, 99(100), 317–342.

Bertschek, I., & Meyer, J. (2008). Do old workers lower IT-enabled productivity? Firm-level evidence from Germany. ZEW Center for European Economic Research Center discussion paper, no. 08-129.

Blanchflower, D. G. (2004). Self-employment: More may not be better. NBER working paper no. 10286.

Bonsang, E., Adam, S., & Perelman, S. (2012). Does retirement affect cognitive functioning? Journal of Health Economics, 31(3), 490–501.

Bonte, W., Falck, O., & Heblich, S. (2009). The impact of regional age structure on entrepreneurship. Economic Geography, 85(3), 269–287.

Borghans, L., & Ter Weel, B. (2002). Do older workers have more trouble using a computer than younger workers? In A. de Grip, J. van Loo, & K. Mayhew (Eds.), The economics of skills obsolescence (pp. 139–173). New York: Emerald Group.

Buddelmeyer, H., Jensen, P. H., & Webster, E. (2010). Innovation and the determinants of company survival. Oxford Economic Papers, 62(2), 261–285.

Cattell, R. B. (1971). Abilities: Their structure, growth and action. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Cefis, E., & Marsili, O. (2006). Survivor: The role of innovation in firm’s survival. Research Policy, 35(5), 626–641.

Clegg, A., & Fifer, S. (2014). Senior self-employment and entrepreneurship—A PRIME perspective. Public Policy & Aging Report, 24(4), 168–172.

Colovic, A., & Lamotte, O. (2012). Entrepreneurs seniors et innovation. Revue Française de Gestion, 227, 127–141.

Curran, J., & Blackburn, R. (2001). Older people and the enterprise society: Age and self-employment propensities. Work Employment and Society, 15(4), 889–902.

Czarnitzki, D., & Delanote, J. (2012). Young innovative companies: The new high-growth firms? Industrial and Corporate Change, 22(5), 1315–1340.

Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social capital and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331.

Dencker, J. C., & Gruber, M. (2015). The effects of opportunities and founder experience on new firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 36(7), 1035–1052.

Desjardins, R., & Warnke, A. J. (2012). Ageing and skills: A review and analysis of skill gain and skill loss over the lifespan and over time. OECD education working paper, n° 72, 2012.

Fairlie, R. (2013). 2012 Kauffman index of entrepreneurial activity. Kauffman Foundation.

Fairlie, R. W., & Krashinsky, H. A. (2012). Liquidity constraints, household wealth, and entrepreneurship revisited. Review of Income and Wealth, 58(2), 279–306.

Friedberg, L. (2003). The impact of technological change on older workers: Evidence from data on computer use. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 56(3), 511–529.

Frosch, K. H. (2011). Workforce age and innovation: A literature survey. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(4), 414–430.

Gilly, M. C., & Zeithmal, V. A. (1985). The elderly consumer and adoption of technologies. Journal of Consumer Research, 12(3), 353–357.

Gimmon, E., Yitshaki, R., & Hantman, S. (2016). Entrepreneurship in the third age: Retirees’ motivation and intentions. In Academy of management proceedings (Vol. 2016, No. 1, p. 15055). Academy of Management.

Halvorsen, C. J., & Morrow-Howell, N. (2016). A conceptual framework on self-employment in later life: Toward a research agenda. Work, Aging and Retirement, 3(4), 313–324.

Harada, N. (2003). Who succeeds as an entrepreneur? An analysis of the post-entry performance of new firms in Japan. Japan and the World Economy, 15(2), 211–222.

Hertzog, C., Kramer, A. F., Wilson, R. S., & Lindenberger, U. (2008). Enrichment effects on adult cognitive development. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(1), 1–65.

Hoetker, G. (2007). The use of logit and probit models in strategic management research: Critical issues. Strategic Management Journal, 28(4), 331–343.

Hudson, R. B., & Goodwin, J. (2014). Hardly an oxymoron: Senior entrepreneurship. Public Policy & Aging Report, 24(4), 131–133.

Isele, E., & Rogoff, E. G. (2014). Senior entrepreneurship: The new normal. Public Policy & Aging Report, 24(4), 141–147.

Josef, A. K., Richter, D., Samanez-Larkin, G. R., Wagner, G. G., Hertwig, R., & Mata, R. (2016). Stability and change in risk-taking propensity across the adult life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(3), 430–450.

Kautonen, T. (2013). A background paper for the OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs and Local Development. OECD.

Kautonen, T., & Minniti, M. (2014). ‘Fifty is the new thirty’: Ageing well and start-up activities. Applied Economics Letters, 21(16), 1161–1164.

Kautonen, T., Tornikoski, E. T., & Kibler, E. (2011). Entrepreneurial intentions in the third age: The impact of perceived age norms. Small Business Economics, 37(2), 219–234.

Kautonen, T., Kibler, E., & Minniti, M. (2017). Late-career entrepreneurship, income and quality of life. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(3), 318–333.

Kelley, D., Ali, A., Brush, C., Corbett, A., Lyons, T., Majbouri, M., & Rogoff, E. (2013). 2013 United States Report, GEM National Entrepreneurial Assessment for the United States of America. Babson College.

Kibler, E., Wainwright, T., Kautonen, T., & Blackburn, R. (2015). Can social exclusion against “older entrepreneurs” be managed? Journal of Small Business Management, 53(S1), 193–208.

Koellinger, P. (2008). Why are some entrepreneurs more innovative than others? Small Business Economics, 31(1), 21–37.

Koning, J., & Gelderblom, A. (2006). ICT and older workers: No unwrinkled relationship. International Journal of Manpower, 27(5), 467–490.

Lamotte, O., & Colovic, A. (2013). Do demographics influence aggregate entrepreneurship? Applied Economics Letters, 20(13), 1206–1210.

Lee, S. Y., Florida, R., & Acs, Z. (2004). Creativity and entrepreneurship: A regional analysis of new firm formation. Regional Studies, 38(8), 879–891.

Lévesque, M., & Minniti, M. (2006). The effect of aging on entrepreneurial behavior. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(2), 177–194.

Low, M. B., & MacMillan, I. C. (1988). Entrepreneurship: Past research and future challenges. Journal of Management, 14(2), 139–161.

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. The Academy of Management Journal, 21(1), 135–172.

Lunsford, D. A., & Burnett, M. S. (1992). Marketing product innovations to the elderly: Understanding the barriers to adoption. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 9(4), 53–62.

Maâlaoui, A., Castellano, S., Safraou, I., & Bourguiba, M. (2013). An exploratory study of seniorpreneurs: A new model of entrepreneurial intentions in the French context. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 20(2), 148–164.

Maula, M., Murray, G., & Jääskeläinen, M. (2007). Public financing of young innovative companies in Finland. Ministry of Trade and Industry, Finland.

McMullen, J. S., Bagby, D. R., & Palich, L. E. (2008). Economic freedom and the motivation to engage in entrepreneurial action. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(5), 875–895.

Meyer, J. (2011). Workforce age and technology adoption in small and medium-sized service firms. Small Business Economics, 37(3), 305–324.

Minniti, M., & Nardone, C. (2007). Being in someone else’s shoes: The role of gender in nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 28(2–3), 223–238.

Minola, T., Criaco, G., & Cassia, L. (2014). Are youth really different? New beliefs for old practices in entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 18(2–3), 233–259.

Mueller, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship in the region: Breeding ground for the nascent entrepreneurs? Small Business Economics, 27(1), 41–58.

Parker, S. C. (2004). The economics of self-employment and entrepreneurship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reynolds, P. D. (2007). New firm creation in the United States a PSED I overview. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 3(1), 1–150.

Rietzschel, E. F., Zacher, H., & Stroebe, W. (2016). A lifespan perspective on creativity and innovation at work. Work, Aging and Retirement, 2(2), 105–129.

Ruth, K.-E., & Birren, J. E. (1985). Creativity in adulthood and old age: Relations to intelligence, sex and mode of testing. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 8(1), 99–109.

Schneider, C., & Veugelers, R. (2010). On young highly innovative companies: Why they matter and how (not) to policy support them. Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(4), 969–1007.

Schøtt, T., Rogoff, E., Herrington, M., & Kew, P. (2017). GEM special report on senior entrepreneurship. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association, 2017.

Stirzaker, R. J., & Galloway, L. (2017). Ageing and redundancy and the silver lining of entrepreneurship. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 18(2), 105–114.

Thornhill, S. (2006). Knowledge, innovation and firm performance in high- and low-technology regimes. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(5), 687–703.

Valenzuela, M. J., & Sachdev, P. (2006). Brain reserve and dementia: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 36(4), 441–454.

Wainwright, T., & Kibler, E. (2014). Beyond financialization: Older entrepreneurship and retirement planning. Journal of Economic Geography, 14(4), 849–864.

Wainwright, T., Hill, K., Kibler, E., Blackburn, R., & Kautonen, T. (2011). Who are you calling old?: Revisiting notions of age and ability amongst older entrepreneurs. In 34th ISBE annual conference, 9–10 November, 2011, Sheffield, UK.

Weinberg, B. (2004). Experience and technology adoption. IZA discussion papers, No-1051.

Welter, F. (2011). Contextualizing entrepreneurship – Conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 165–184.

Zahra, S. A., Wright, M., & Abdelgawad, S. G. (2014). Contextualization and the advancement of entrepreneurship research. International Small Business Journal, 32(5), 479–500.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Colovic, A., Lamotte, O., Bayon, M.C. (2019). Technology Adoption and Product Innovation by Third-Age Entrepreneurs: Evidence from GEM Data. In: Maâlaoui, A. (eds) Handbook of Research on Elderly Entrepreneurship. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13334-4_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13334-4_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-13333-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-13334-4

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)