Abstract

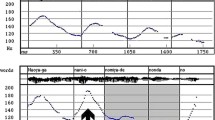

This study investigates the reason why wh phrases are illegitimate in postverbal positions in Turkish while they are free to scramble in the preverbal area. The common view in the literature is that prosodic and interpretive properties of focus and wh phrases, i.e. taking obligatory primary stress and being non-recoverable, are inconsistent with the properties of the postverbal field, which is a destressed area reserved for backgrounded elements. Focusing mainly on wh data, this study proposes that phonological and interpretive effects of postverbal wh phrases that cause ungrammaticality can be derived from overt syntax. Building on empirical facts revealing the scope of focus is read directly from overt syntax, it is proposed that a postverbal wh phrase, being a variable, stays in a position where it cannot be bound by its operator, hence the ungrammaticality.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

In a similar vein, Şener (this volume), working under the cartographic approach (Rizzi 1997), argues for the existence of two projections in the split-CP area that are dedicated to discourse anaphoric (DA) elements, which mark given/topical/backgrounded information or the familiarity topic: DaP1 and DaP2. Like Julien’s (2002) lower TopP, DaP2 is located in a lower position, right above IP and below DaP1, and hosts postverbal elements that move to its rightward Spec to check [discourse anaphoric] features. It is, thus, similar to Julien’s proposal in that in both movement of postverbal elements is triggered by the need to check a syntactic topic-like feature of a head whose Spec position is a dedicated place for them, although they differ with respect to the direction of the Spec position and how movement to the position in question takes place (a la Kayne (1994) in Julien, and via standard rightward movement in Şener). As Şener does not discuss the left versus right asymmetry regarding focus/wh phrases, which is the topic focused in the present paper, I do not go into further details of his study. I refer interested reader to his chapter to have more detail about his system.

- 2.

Although the operator-variable analysis of wh phrases has been assumed in most studies in the literature, Ramchand (1996) argues for the claim that “… in Bengali, and not in English, questions are constructed from explicitly alternative-inducing elements, and not from formal operators” (p. 21). In this analysis, wh words are not variables bound by operators. A reviewer thinks that this Alternative Semantics (Hamblin 1973; Rooth 1992, among others) analysis is also viable in Turkish. This may in fact be on the right track, but in the absence of a detailed comparison between the two accounts regarding the case in Turkish, and also bearing in mind that in this analysis “… the semantic contribution [of semantic and pragmatic elements] … produce[s] the same effects as an operator structure” (Ramchand 1996, p. 2), I prefer to stick to the operator-variable analysis for the rest of the paper. Also, I would like to thank the reviewer for drawing my attention to this point and pointing out the references mentioned.

- 3.

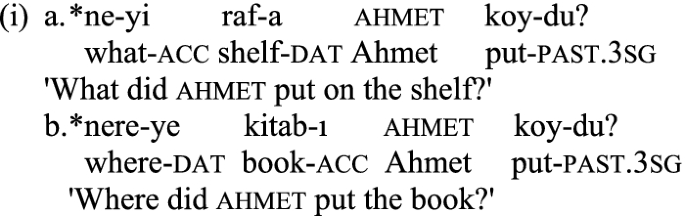

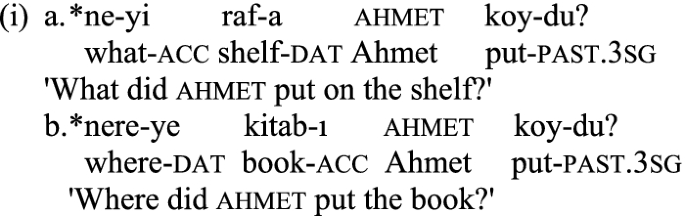

Primary stress can also be assigned to the left of the wh phrase but this is acceptable only when the argument receiving the primary stress denotes an alternative in a contextually given set. For example, (i) is an acceptable question if the focused DP kitabı ‘the book’ denotes an alternative in such a context set where the speaker knows, for example, who gave the newspaper and asks who was it that gave the book. We will discuss these cases in Sect. 2.2 in relation to (13)–(15).

- 4.

As before, in (5)–(8) small capitals indicate the item with H*-marking that has matrix scope. The accent on the stressed syllable of the wh phrases as well as immediately preverbal phrases in the embedded clauses indicates that they receive the most prominent stress in the embedded clause.

- 5.

In this context, the most prominent stress in the embedded clause can be regarded as sentential stress canonically assigned to the immediately preverbal item. On the other hand, one could still analyze it as marking the focus of the embedded clause (see e.g. Hoffman 1995). Although it could be a possible analysis, it is quite difficult to test this hypothesis since the clause that this stress appears in is obligatorily interpreted as presupposed, as discussed in the text. So, I will stick to the accepted view that focus is a matrix phenomenon.

- 6.

Göksel (2013) does not directly discuss postverbal wh phrases but in footnote 14 (p. 18) states that the trochee analysis “… can straightforwardly be extended to cover wh-questions as well”.

- 7.

- 8.

Kornfilt (1997, p. 28) also gives examples of this generalization, i.e. *wh…F, with regard to sentence-initial wh phrases occurring with a focused subject DP in the immediately preverbal position (small capitals in the examples, but not in the English translations, are mine):

- 9.

Based on the following example, a reviewer rejects the view that in Turkish focus should always receive primary stress. For her/him, sadece ‘only’ is a focus operator that binds the DP peynirle ‘with cheese’ in (i), which is focused but not marked by primary stress. From this, it follows that the generalization that focus and wh phrases differ with respect to primary stress cannot be correct.

However, when uttering (i), the speaker should already know that ‘Ali fed something only with cheese’, which means that this part of the sentence is presupposed leaving the wh phrase as the only focused item in the sentence. Note that the declarative counterpart of (i) has the same presupposition (even in the absence of the question in (i) in the context set):

Therefore, there seems to be no reason in the empirical grounds not to agree with the widely accepted view that in Turkish focused phrases should receive primary stress.

- 10.

In overt syntax, this means it projects upwards. Also, for a brief analysis of focus projection in Turkish, see Kamali (2011).

- 11.

References

Aboh, E.O. 2007. Focused versus non-focused wh-phrases. In Focus strategies in African languages: The interaction of focus and grammar in Niger-Congo and Afro-Asiatic, ed. E. Aboh, K. Hartmann, and M. Zimmermann, 287–314. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Beck, S. 1996. Quantified structures as barriers for LF movement. Natural Language Semantics 4: 1–56.

Beck, S., and S.-S. Kim. 1997. On wh- and operator scope in Korean. Journal of Eastern Asian Linguistics 6: 339–384.

Choe, Hyon Sook. 1995. Focus and topic movement in Korean and licensing. In Discourse configurational languages, ed. K.E. Kiss, 269–334. Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, N. 2001. Derivation by Phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. M. Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Cruschina, S. 2011. Discourse-related features and functional projections. New York: Oxford University Press.

Erguvanlı, E. 1984. The function of word order in Turkish Grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Erkü, F. 1983. Discourse pragmatics and word order in Turkish. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, University of Minnesota.

Frascarelli, M., and A. Puglielli. 2008. Focus in the Force-Fin system. Information structure in Cushitic languages. In Focus strategies: Evidence from African languages, ed. E. Aboh, K. Hartmann, and M. Zimmermann, 161–184. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Göksel, A. 1998. Linearity, focus and the postverbal position in Turkish. In The Mainz Meeting: Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Turkish Linguistics, ed. L. Johanson, 85–106. Weisbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Göksel, A., and S. Özsoy. 2000. Is there a focus position in Turkish? In Studies on Turkish and Turkic Languages: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Turkish Linguistics, August 12–14, 1998, ed. A. Göksel, and C. Kerslake, 219–228. Weisbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag.

Göksel, A. 2009. A phono-syntactic template for Turkish: Base-generating free word order. Ms. Boğaziçi University.

Göksel, A. 2013. Flexible word order and the anchors of the clause. SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics 16: 3–25.

Göksel, A., and C. Kerslake. 2005. Turkish: A comprehensive grammar. London, New York: Routledge.

Görgülü, E. 2006. Variable wh-words in Turkish. Unpublished M.A. thesis, Boğaziçi University, İstanbul, Turkey.

Gracanin-Yüksek, M., and S. İşsever. 2011. Movement of bare objects in Turkish. Dilbilim Araştırmaları, 2011/1, 33–49. Boğaziçi University Press.

Hamblin, C.L. 1973. Questions in montague english. Foundations of Language 6: 41–53.

Hoffman, B. 1995. The computational analysis of the syntax and interpretation of ‘‘Free’’ word order in Turkish. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Pennsylvania.

Horvath, J. 1986. Focus in the theory of grammar and the syntax of Hungarian. Dordrecht: Foris.

İşsever, S. 2000. Türkçede Bilgi Yapısı. Doctoral Dissertation. Ankara University.

İşsever, S. 2003. Information structure in Turkish: The word order-prosody interface. Lingua 113 (11): 1025–1053.

İşsever, S. 2007. Towards a unified account of clause-initial scrambling in Turkish: A feature analysis. Turkic Languages 11 (1): 93–123.

İşsever, S. 2008. EPP driven scrambling and Turkish. In Ambiguity of morphological and syntactic analyses, ed. T. Kurebito, 27–41. Tokyo: Tokyo University of Foreign Studies (Research Institute for Languages of Asia and Africa [ILCAA]) Press.

İşsever, S. 2009. A syntactic account of wh-in-situ in Turkish. In Essays on Turkish Linguistics: Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Turkish Linguistics (August 6–8, 2008), ed. S. Ay, Ö. Aydın, İ. Ergenç, S. Gökmen, S. İşsever, and D. Peçenek, 103–112. Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz Verlag.

Jackendoff, R. 1972. Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Jiménez-Fernández, Á., and S. İşsever. 2013. Deriving A/A′-effects in topic fronting: Intervention of focus and binding. In Generative linguistics in Wroclaw No. 2, current issues in generative linguistics: Syntax, semantics and phonology, ed. J. Blaszczak, B. Rozwadowska, and W. Witkowski, 8–25. Wroclaw: University of Wroclaw Center for General and Comparative Linguistics (CGCL).

Julien, Marit. 2002. Syntactic heads and word formation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kamali, B.A.A. 2011. Topics at the PF interface of Turkish. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University.

Kayne, R.S. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Linguistic Inquiry Monographs. MIT Publishing.

Kennelly, S.D. 1997. The presentational focus position of nonspecific objects in Turkish. In Proceedings of the VIIIth International Conference on Turkish Linguistics, ed. K. İmer, and N.E. Uzun, 25–36. Ankara: Ankara University Press.

Kılıçaslan, Y. 1994. Information Packaging in Turkish. Unpublished MSc. Thesis, University of Edinburgh.

Kılıçaslan, Y. 1998. A form-meaning interface for Turkish. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Edinburgh.

Kılıçaslan, Y. 2004. Syntax of information structure in Turkish. Linguistics 42 (4): 717–765.

Kim, S.-S. 2002. Intervention effects are focus effects. In Japanese/Korean linguistics, vol. 10, ed. N. Akatsuka, and S. Strauss, 615–628. Stanford: CSLI.

Kornfilt, Jaklin. 1997. Turkish. London, New York: Routledge.

Kornfilt, J. 2005. Asymmetries between pre-verbal and post-verbal scrambling in Turkish. In The free word order phenomenon, its syntactic sources and diversity, ed. J. Sabel and M. Saito, 163–179. Berlin, New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kural, M. 1992. Properties of scrambling in Turkish. Manuscript, ver.1. UCLA.

Kural, M. 1997. Postverbal constituents in Turkish and the linear correspondence axiom. Linguistic Inquiry 28–3: 498–519.

Kural, M. 2005. Tree traversal and word order. Linguistic Inquiry 36 (3): 367–387.

Mahajan, A. 1990. The A/A′ distinction and movement theory. Doctoral Dissertation, MIT.

Miyagawa, S. 1997. Against optional scrambling. Linguistic Inquiry 28: 1–25.

Miyagawa, S. 2003. A-movement scrambling and options without optionality. In Word order and scrambling, ed. S. Karimi, 177–200. Oxford: Blackwell.

Özge, U., and C. Bozşahin. 2010. Intonation in the grammar of Turkish. Lingua 120: 132–175.

Öztürk, B. 2005. Case, referentiality and phrase structure. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Ramchand, G. 1996. Questions, polarity and Alternative semantics. Available at http://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/000183/.

Reinhart, T. 1982. Pragmatics and linguistics: An analysis of sentence topics. Philosophica 27: 53–94.

Rizzi, L. 1990. Relativized minimality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rizzi, L. 1997. On the fine structure of the left-periphery. In Elements of grammar, ed. L. Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Rochemont, M.S. 1986. Focus in generative grammar. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Rooth, M. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75–116.

Şener, S. (this volume). Eliminating scrambling: The variation of word order in Turkish.

Steedman, M. 2000. Information structure and the syntax-phonology interface. Linguistic Inquiry 31 (4): 649–689.

Temürcü, C. 2005. The interaction of syntax and discourse in word order: Data from Turkish. Dilbilim ve Uygulamaları, 123–159. İstanbul: Multilingual.

Vallduví, E., and E. Engdahl. 1996. The linguistic realization of information packaging. Linguistics 34: 459–519.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the reviewer for his/her valuable and helpful comments. All errors are of course my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

İşsever, S. (2019). On the Ban on Postverbal wh Phrases in Turkish: A Syntactic Account. In: Özsoy, A. (eds) Word Order in Turkish. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, vol 97. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11385-8_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11385-8_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-11384-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-11385-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)